Abstract

Tendinopathy is a common and significant clinical problem characterised by activity‐related pain, focal tendon tenderness and intratendinous imaging changes. Recent histopathological studies have indicated the underlying pathology to be one of tendinosis (degeneration) as opposed to tendinitis (inflammation). Relatively little is known about tendinosis and its pathogenesis. Contributing to this is an absence of validated animal models of the pathology. Animal models of tendinosis represent potential efficient and effective means of furthering our understanding of human tendinopathy and its underlying pathology. By selecting an appropriate species and introducing known risk factors for tendinopathy in humans, it is possible to develop tendon changes in animal models that are consistent with the human condition. This paper overviews the role of animal models in tendinopathy research by discussing the benefits and development of animal models of tendinosis, highlighting potential outcome measures that may be used in animal tendon research, and reviewing current animal models of tendinosis. It is hoped that with further development of animal models of tendinosis, new strategies for the prevention and treatment of tendinopathy in humans will be generated.

Keywords: collagen, connective tissue, tendinitis, tendinosis, tendon

Tendinopathy (tendino‐ = tendon; ‐pathy = disease) is a clinical condition characterised by activity‐related pain, focal tendon tenderness and intratendinous imaging changes. It represents a common and significant problem, with a prevalence of 14% in elite athletes1 and requiring a recovery time of three to six months with first‐line conservative management.2 Despite its clinical significance, only recently have strides been made in understanding the pathology underlying tendinopathy. Historically, it was thought to be one of inflammation and, consequently, the condition was labeled as ‘tendinitis'. However, recent histopathological studies have shown the underlying pathology to be primarily one of tendon degeneration (tendinosis).3,4,5 Given this recent identification of the underlying pathology, little is known about its pathophysiology. This has restricted treatment options, with many current interventions being based on theoretical rationale and clinical experience rather than manipulation of underlying pathophysiological pathways.6 Contributing to this lack of understanding of tendinopathy is an absence of validated animal models of the underlying pathology. In order to further our understanding of tendinopathy, suitable animal models of tendinosis are required. This paper overviews the role of animal models in tendinopathy research by discussing the benefits and development of animal models of tendinosis, highlighting potential outcome measures that may be used in animal tendon research, and reviewing current animal models of tendinosis.

Benefits of animal models of tendinosis

The benefits of animal research to the understanding of human disease are without question. Virtually every medical achievement of the last century depended directly or indirectly on research with animals.7 In these previous applications, animal models both complemented and directed clinical research. Animal models allowed clinical observations and hypotheses to be explored in great depth, while novel findings derived in animal models were translated to the clinical setting. As a result of this interdependence, animal research typically evolves simultaneously with clinical research, and both constantly change as knowledge about a particular disease or illness learnt from one model is applied to the other.

The use of animal models for the study of tendons is not new, but has gained popularity in synchrony with the increasing clinical interest in tendinopathy. While many studies performed in animals could theoretically be performed in humans, the use of animal models of tendinosis has a number of benefits over similarly designed research in humans. Primarily, animal models enable studies to be performed using in‐depth invasive analyses at the organ, tissue and molecular levels. It is possible to assess human tendons at similar levels by obtaining samples via biopsy8 and surgery,3,9,10,11 or harvesting tissue post mortem;3,9 however, these methods are typically not feasible because of the invasive nature of the procedures and the need to obtain viable tissue samples from large groups of both pathological and normal tendons. In addition, human tendon tissue obtained by invasive procedures typically has well‐established chronic pathology and, thus, does not lend itself to the study of tendinopathy pathogenesis.

The ability to perform invasive analyses in animal models provides researchers with powerful tools to advance understanding of many aspects of tendinosis. By elucidating early changes associated with tendinosis development in animal tendons, pathogenic pathways may be discovered, potentially leading to the development of preventative strategies. These pathways are near impossible to explore in humans as initial changes associated with tendinopathy precede the onset of symptoms and it is difficult to justify harvesting asymptomatic tendon tissue from humans. Animal models also permit more in‐depth investigation of changes associated with established tendinosis, allowing current interventions to be validated and potential novel targets to be revealed. In terms of the latter, the Food and Drug Administration in the United States requires novel compounds to undergo pre‐clinical evaluation in animal models to establish their efficacy and safety before use in clinical trials. A prerequisite for this in tendinopathy research is the establishment of animal models of tendinosis.

Animal models facilitate the search for novel pathogenic pathways by providing researchers with the flexibility to control variability. For instance, in animal models it is possible to isolate the effects of single genetic or environmental variables while controlling other potential confounders. This is difficult to perform in clinical studies because of the vast differences in genetic and environmental backgrounds among individuals, which results in large variability and the need for large sample groups in order to achieve sufficient statistical power.

Development of tendinosis in animal models

For animal models of tendinosis to result in clinically relevant and translatable outcomes, careful consideration needs to be given to model development. The most important requirement of any animal model is its ability to provide reproducible results that are consistent with the human condition.

Selection of appropriate species

The initial step in the development of an animal model is the selection of an appropriate species. As there is no animal with exactly the same characteristics as those of humans, no one species represents the ‘gold standard'. This is reflected by previous studies which have used a wide range of species as models for tendon injuries, including non‐human primates, horses, goats, dogs, rabbits, rats and mice.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24

From a translational standpoint, non‐human primates represent the most ideal species to use in tendon research as they are the closest to humans in terms of anatomy and physiology. However, their use is limited by ethical considerations and a lack of availability which results in extraordinary high costs (table 1). As such, they are not likely to be widely used as models for overuse tendon injuries. Large animal models such as horses, goats and dogs have advantages as animal models as they have naturally occurring tendinosis.25,26 However, on account of their large size they frequently need a minimum of two investigators for handling, and their purchase and housing costs are significantly greater than those of smaller species.

Table 1 Purchase and housing costs for animal models of tendinosis.

| Species | Purchase cost ($)* | Housing cost ($/day)* |

|---|---|---|

| Non‐human primate† | 3500–5000 | 15–20 |

| Horse | 500–1500 | 10–15 |

| Goat | 100–500 | 10–15 |

| Dog | 100–500 | 10–15 |

| Rabbit | 40–100 | 3–5 |

| Rat | 25 | 0.4–0.6 |

| Mouse | 5 | 0.2–0.4 |

*US dollars

†Data for rhesus macaque.

Small species such as rabbits, rats and mice are by far the most popular and convenient species to study as animal models of tendinosis. Rabbits are popular as their cellular and tissue physiology approximates that of humans27 and they are mild‐tempered and relatively easy to handle. The main disadvantages of rabbits are their purchase and housing costs, which are approximately three‐ and ten‐times that of rats, respectively (table 1). A further disadvantage is their susceptibility to serious, life‐threatening injury (fracture/dislocation at the lumbosacral junction) when suddenly frightened.

Rats and mice (rodents) have distinct advantages over other species as animal models. They have short gestation periods, generate multiple offspring and have rapid growth rates and short life spans, enabling studies to be performed efficiently. They also have mild temperaments, enabling ease of handling, and are relatively inexpensive as they are readily available and require low maintenance. In terms of being actual models for humans, rats and mice represent very useful species as their anatomy and physiology are homologous with humans. For instance, both species possess similar limb anatomy as humans (fig 1),21 including the tendons that are prone to tendinopathy in humans (ie, Achilles, patellar and supraspinatus tendons).

Figure 1 Comparative osteology of the shoulder girdle in humans and rats. Despite subtle differences, both species possess similar gross anatomy of their scapulo‐humero‐clavicular region. In both species the supraspinatus muscle originates from the supraspinous fossa and travels laterally under the coracoacromial arch to attach to the greater tubercle of the humerus. It is potentially susceptible to compression within the subacromial space in both species (reprinted from Soslowsky LJ, Carpenter JE, DeBano CM, et al. Development and use of an animal model for investigations on rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1996;5:383–92, with permission from Elsevier).

The homology between humans and rodents is reflected genomically. To date, the sequence of three mammalian genomes have been sequenced–human,28,29 mouse30 and rat.31 Comparative mammalian genomics has indicated that as many as 80–90% of rodent genes have matches in humans. This cross‐species homology enables rodents to be similar enough to humans to provide useful translational experimental data.32

The sequencing of the rat and, in particular, mouse genome has increased the attraction of rodents for research. Outbred (genetically diverse) and inbred (genetically identical) strains of rodents have been available for many years; however, the sequencing of each species' genome has made it possible to genetically engineer animals that have a specific gene either knocked‐out or knocked‐in. Such transgenic animals have already been utilised in tendon research,33,34,35,36,37 where they represent potentially useful tools for understanding the pathogenesis of tendinosis. For instance, by creating a null mutation in the gene encoding for a particular pathway molecule, it may be possible to determine the influence of that particular gene product on tendinosis initiation and progression.

Rats may represent a better species than mice as an animal model of tendinosis. This primarily results from their larger size and, subsequently, bigger tendons. The latter makes rat tendons more amenable to surgery and the harvesting of adequate amounts of tissue for the execution of useful outcome measures. In addition, rats are reportedly easier to work with than mice as they are less aggressive and readily trained.32 The benefits of rats over mice as an animal model of tendinosis are confirmed by previous studies which have developed tendinosis in rat tendons.21,38 Tendinosis has yet to be developed in a mouse model, to the author's knowledge. The main limitation of rats compared to mice is the current limited number of transgenic strains, for it has proven more difficult to generate transgenic rats compared to mice. However, this is currently being addressed and it is possible through breeding schemes to develop inbred strains of rats that differ by single chromosomes (congenic rats). In the near future, more transgenic rat lines will become available.

Pathology of tendinosis in humans

To develop an animal model of tendinosis, the model needs to be validated against the condition in humans. The pathology and pathophysiology of tendinopathy in humans is currently poorly understood, making validation of animal models difficult. However, two common and established features associated with tendinopathy in humans are histopathological changes and mechanical weakening of the tendon.

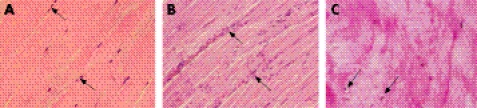

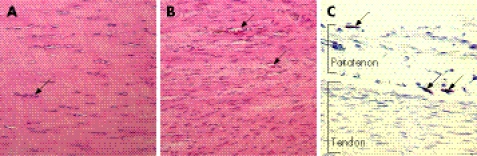

Histopathological studies have consistently shown that tendinopathy in humans is typically due to tendinosis.3,4,5 Tendinosis in humans is characterised histologically by tissue degeneration with a failed reparative response and an absence of inflammatory cells (fig 2).3,5,39,40,41,42 The pathological region is distinct from normal tendon with both matrix and cellular changes. Instead of clearly defined, parallel and slightly wavy collagen bundles, tendinosis is associated with relative expansion of the tendinous tissue, loss of the longitudinal alignment of collagen fibers and loss of the clear demarcation between adjacent collagen bundles.3,5,39,40,41 Multiple cellular changes co‐exist with these matrix changes. The most obvious is hypercellularity resulting from an increase in cellular proliferation.5,43 There is atypical fibroblast and endothelial cellular proliferation39,44 and extensive neovascularisation.3,41,44,45,46 The collagen‐producing tenocytes lose their fine spindle shape5,47 and their nuclei appear more rounded and sometimes chondroid in appearance, indicating fibrocartilaginous metaplasia.2

Figure 2 Histopathological changes seen with tendinopathy in humans. In the normal tendon (A), note the uniform appearance of tightly packed, well‐aligned collagen fibrils with interspersed tenocytes aligned parallel to the fibrils (arrows). (B) Slightly pathological tendinous tissue with initial matrix disorganisation and evident hypercellularity (arrows). (C) Highly degenerated tendon with some chondroid cells (arrows), yet absence of inflammatory cells (reprinted from Rees JD, Wilson AM, Wolman RL. Current concepts in the management of tendon disorders. Rheumatology 2006;45:508–21, with permission from the British Society for Rheumatology).

As a consequence of the above tissue changes, there is mechanical weakening of the afflicted tendon when tendinosis is present. Tendons must be able to withstand large‐magnitude tensile loads in their function of transmitting muscle contractile forces necessary for human motion. However, when tendinosis is present the ability to accomplish this is compromised. This is evidenced by a propensity for afflicted tendons to undergo mechanical failure (complete tendon rupture). This was most elegantly demonstrated by Kannus and Jozsa9 who showed that degenerative pathological changes pre‐existed in 97% of spontaneously ruptured tendons. Similar findings have been found by other authors, with rotator cuff tears48 and patellar49 and Achilles50,51,52 tendon ruptures all being associated with underlying tendinosis.

To be considered a valid animal model of tendinosis, the model needs primarily to replicate the above histopathological and mechanical features of the condition as they occur in humans. As new findings in humans are derived and established, the animal model needs to be re‐evaluated and re‐validated. For instance, recent molecular studies performed on human tendon samples have demonstrated tendinopathy to be associated with distinct changes in gene expression and matrix turnover.53 Once these changes become more firmly established in human tendon samples, their presence needs to be confirmed in the available animal models in order to reconfirm the models' validity.

Risk factors for tendinosis in humans

The most logical approach to generating tendinosis in an animal model is to introduce known and potential pathogenic factors for the condition in humans. Unfortunately, the precise mechanism by which tendinopathy develops in humans is currently unknown. As with other overuse conditions, its development is likely to be caused by a range of factors with the relative contribution of each varying among individuals. Clinically, these factors are typically grouped into extrinsic and intrinsic risk factors.

Extrinsic factors are most commonly indicted in the pathogenesis of tendinopathy, with the most frequently reported causative factor being mechanical overload. For tendinopathy to develop, repeated heavy loading of a tendon is typically required. This explains its much higher prevalence in individuals involved in active endeavours. For instance, the age‐adjusted odds ratio for developing Achilles tendinopathy in male master athletes is 14.6, when compared to less active controls.54 Similarly, the odds ratio of developing rotator cuff tendinopathy in heavy manual labourers (bricklayers) is 3.3, when compared to less active foremen.55

Although extrinsic factors are the most consistent causative factor for the development of tendinopathy, its development in some individuals but not in others with equivalent loading indicates that intrinsic factors also contribute. Many intrinsic factors have been postulated as contributors to the development of tendinopathy, including age, gender, body weight, gene polymorphisms, and anatomical and biomechanical variations.56,57,58,59 While isolated introduction of these risk factors typically does not independently cause tendinopathy, their presence may potentiate the development of tendinopathy when they co‐exist with mechanical overload.

Exactly how extrinsic and intrinsic risk factors combine to generate the initial tissue damage for the onset of tendinopathy is not established. Tendons are mechanosensitive and respond and adapt to their mechanical environment.60 However, repeated heavy loading, with or without the presence of one or more intrinsic risk factors, may produce initial pathological changes in either the extracellular matrix (ECM) or cellular components of a tendon.

The ECM theory for the generation of tendinopathy suggests that strains below failure levels are capable of generating damage when introduced repetitively. Healthy tendons are strong, and the safety factor between usual and failure strains in response to load is high. However, it is theorised that a natural phenomenon associated with repetitive sub‐failure strain in tendons is the generation of damage (termed microdamage).61 In most instances, this damage is of little consequence as a tendon is capable of intrinsic repair. This involves the removal of damaged collagen fibrils and their subsequent replacement. A tendon is capable of adapting to its mechanical environment via this mechanism, thereby maintaining its structural integrity. However, under certain conditions imbalances can develop between damage generation and its removal. The subsequent accumulation of damage and associated failed healing attempts is theorised to be the start of a pathology continuum that results in tendinosis and, ultimately, tendon ruptures.

An alternative to the ECM theory is that matrix changes are actually preceded and initiated by cellular changes. This cell‐based theory stems from findings showing that the cells responsible for tendon maintenance display potentially pathological responses to loading. A tendon is primarily maintained by resident tenocytes which have dual functions: (a) as ‘tenoclasts' (teno‐ = tendon, ‐clast = break) by secreting both matrix‐degrading matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and proteoglycan‐degrading metalloendopeptidases (or ‘aggrecanases'); and (b) as ‘tenoblasts' (teno‐ = tendon, ‐blast = to build) by synthesising new ECM. Both of these tenocyte functions are modulated by mechanical loading. For instance, in response to fluid‐induced shear stress, tenocyte expression of house‐keeping, stress response and transport‐related transcripts are up‐regulated, whereas apoptosis, cell division and signaling‐related genes are largely down‐regulated.62 These changes are consistent with an anabolic tendon response. However, tenocytes also exhibit a number of changes in response to loading that are consistent with reduced matrix production and enhanced matrix degradation. These include increased apoptosis63 and synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)64,65 which have been linked to decreased matrix production,66,67 and increased MMP1 expression68 which is suggestive of matrix degradation. It is plausible that these later cellular‐derived changes are involved in the development of tendinopathy.

Factors previously used in animal models

In order to develop tendinosis in an animal model, researchers commonly recreate perturbations reflective of the key risk factors for the condition in humans. This is in an attempt to initiate and produce tendon damage consistent with that observed in humans. As per human risk factors, these can be grouped into extrinsic and intrinsic risk factors.

The most commonly introduced extrinsic risk factor for the development of tendinosis in animal models is mechanical overload. This is intuitive considering the proposed ECM theory for the generation of tendinopathy and because mechanical overload is the most frequently reported causative factor in humans. Mechanical overload of animal tendons has typically been attempted using forced treadmill running,21,69 tendon loading via artificial muscle stimulation70,71,72,73 and direct tendon stretching via an external loading device.38

Treadmill running is commonly employed to induce adaptation in the animal musculoskeletal system; however, it has had variable success in creating overuse tendon pathologies. The predominant reason for this is that studies employing treadmill running have typically used animal species that are habitual runners, such as rodents. Rodents run in excess of 8 km/night in the wild74 and up to 15 km/day in voluntary wheel‐running studies.75,76 This preference for running facilitates acclimation of rodents to treadmill training; however, it makes it difficult to induce overuse injuries in these species as their musculoskeletal systems are inherently adapted for running. To induce pathological changes, the musculoskeletal system needs to be stressed beyond customary levels, but it has proven difficult to force rodents to run at levels in excess of those experienced during voluntary running. For instance, most treadmill studies run animals at speeds less than 20 m/min and for less than 2 hr/day, which equates to a traveled distance of less than 2.5 km/day. Increasing running frequency, duration and/or intensity (increasing belt speed or belt angle from the horizontal) is difficult as it is often coupled with animal resistance and elevated stress.77

Alternative methods of overloading animal tendons are to use artificial muscle stimulation and direct stretching of a tendon. Both methods are usually involuntary as they typically require animal anesthesia, yet they have the advantage of permitting within‐animal studies designs wherein overloaded tendons are compared to contralateral control tendons. Artificial muscle stimulation via electrode stimulation results in tendon loading as tendons function to transmit muscle contractile forces to the skeleton for motion. By coupling muscle stimulation with simultaneous resistance of free segment motion, tendon stress can be elevated. Performing this repetitively may result in tendon degradation and the development of tendinosis. Similarly, tendinosis may be developed by directly stretching a tendon. This requires surgery to enable the tendon to be mechanically lengthened via an external device. As tendons are difficult to grip without creating a compressive injury, direct mechanical loading is really only feasible with the patellar tendon, where the dual bone attachments of the patellar tendon can be distracted without directly damaging the tendon substance.38

Extrinsic factors have had some success in developing tendinosis in animal models;21,38,73 however, success has been restricted to specific situations. For instance, treadmill running successfully generates tendinosis in the rat supraspinatus tendon78 but not the Achilles tendon,69 while artificial muscle stimulation in rabbits generates flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendinosis73 but not Achilles tendinosis.70,72 As a result of this variable success and the fact that the introduction of extrinsic factors is labour intensive, researchers have investigated the role of intrinsic factors in the development of tendinosis in animal models. This typically involves intratendinous injection of chemical compounds, such as collagenase, PGE1, PGE2, corticosteroids and cytokines.15,79,80,81,82,83,84 Introduction of these compounds generates both histological and mechanical changes within the injected tendon; however, their isolated introduction does not appear sufficient to induce the development of a pathology that replicates that observed in human tendons. For instance, collagenase is a frequently reported means of causing animal tendon degeneration as it catalyses the breakdown of collagen and has elevated expression in human tissues with tendinosis.85 However, intratendinous injection of collagenase results in an acute and intense inflammatory reaction (tendinitis),79,86 followed by progressive tendon reparation.21,86 This does not replicate the degenerative pathology (tendinosis) observed in humans. While it is possible that initial tissue changes associated with tendinopathy in humans include inflammatory pathways, these events are thought to be prior to the onset of symptoms and are not evident in the established pathology. Thus, the use of intrinsic factors in isolation is questionable. The best approach may be to combine these with an extrinsic factor given the apparent dependence of human tendinopathy on mechanical overload. This approach has been shown to result in greater degeneration of the rat supraspinatus tendon.21,22,87

Outcome measures in animal models of tendinosis

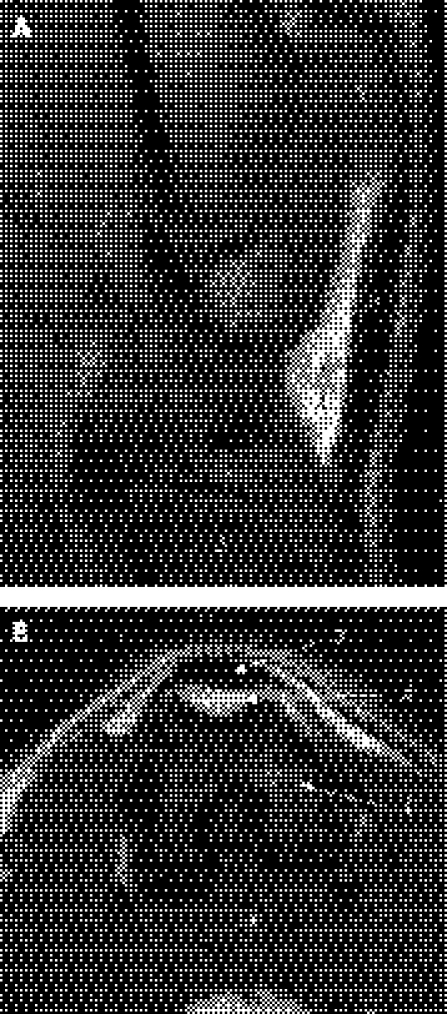

A wide range of outcomes can be employed in animal models of tendinosis, with their selection dependent upon the specific research question. To confirm the presence of tendinosis in an animal model, it is possible to perform in vivo imaging to obtain clinically translatable outcomes. For instance, a number of high‐frequency ultrasound biomicroscopy systems are commercially available that enable animal tendons to be visualised ultrasonically with high spatial resolution (30–50 μm).88 These systems feature common clinical ultrasound imaging modes, such as 2‐D (B‐scan) imaging and power Doppler, and may be used to detect the presence of hypoechoic regions and microcirculation in animal models of tendinosis, respectively. Similarly, the advent of stronger magnetic fields (in excess of 7.0T) have allowed for the development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems that have better signal‐to‐noise ratios and stronger gradients. This has improved the spatial resolution of MRI images to 10–50 μm,89 which is more than adequate for imaging of small animal tendons (fig 3).90

Figure 3 High‐resolution magnetic resolution imaging (MRI) of the rat knee using a 4.7T magnetic resonance system. (A) spin echo proton density‐weighted sagittal MRI (time of repetition [TR]/time of echo [TE], 1.000/0.009 s; slice thickness, 1.5 mm, in‐plane resolution = 118 μm×118 μm). (B) spin echo T1 weighted transverse MRI (time of repetition [TR]/time of echo [TE], 0.3/0.009 s; slice thickness, 1.0 mm, in‐plane resolution = 118 μm×160 μm). 1 = femur; 2 = patella; 3 = patellar tendon; 4 = infrapatellar fat pad; 5 = proximal tibia (reprinted from Wang Y‐XJ, Kuribayashi H, Westwood FR. Some aspects of rat femorotibial joint microanatomy as demonstrated by high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Lab Anim 2006;40:288–95, with permission from the Royal Society of Medicine Press on behalf of Laboratory Animals Limited).

In vivo imaging in animal models potentially enables the obtainment of clinically translatable outcomes. However, the true benefit of animal models of tendinosis derives from the ability to perform a wide range of ex vivo outcome measures at all levels, including organ, tissue and molecular levels (table 2). While it is possible to perform these measures in human tendon samples, this is typically not feasible or efficient because of the invasive nature of the procedures and the need to obtain viable tissue samples from a large sample of both pathological and normal tendons.

Table 2 Ex vivo outcome measures possible in animal models of tendinosis.

| Outcome | |

|---|---|

| Organ level | |

| Observation | Macroscopic appearance |

| Scale | Tendon weight and water content |

| Calipers or micrometer | Morphometry |

| Mechanical testing | Low‐ and high‐load mechanical properties |

| Tissue level | |

| Histology | Histopathology |

| Immunohistochemistry | Localisation of cellular and tissue constituents |

| In situ hybridisation | Localisation of specific DNA or RNA sequences |

| Electron microscopy | Collagen fibril organisation and morphology, and tenocyte ultrastructure |

| Molecular level | |

| Microarray analysis | Transcriptional/translational expression profiling |

| Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | Transcriptional expression levels |

| Mass spectrometry | Chemical composition |

| Chromatography | Tissue composition |

| Western blots | Protein expression and modification |

| Electrophoresis | Protein expression |

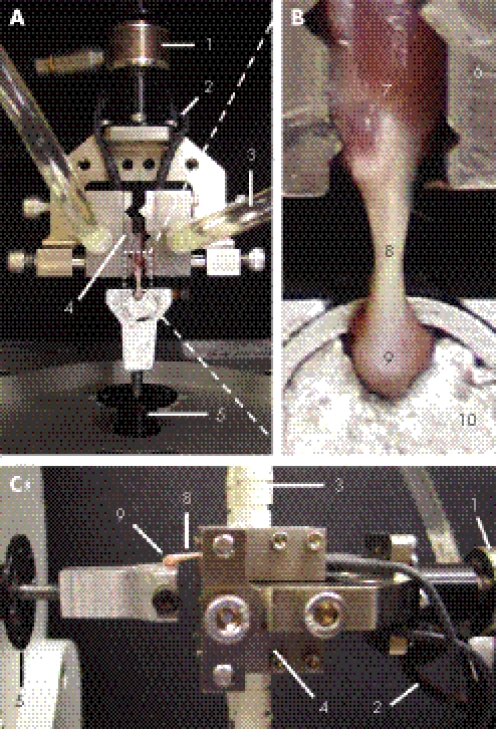

The primary ex vivo measures of interest in animal models of tendinosis are the mechanical properties of the tendon. Reduced mechanical properties resulting in an increased likelihood of spontaneous rupture are the ultimate consequence of clinical tendinosis.9 Mechanical testing with careful consideration to testing set‐up can been performed on both large (ie, horse)91 and small (ie, mouse)36,92 animal tendons (fig 4). Key variables of interest include both low‐ and high‐load properties. Low‐load properties provide information on viscoelastic properties (eg, creep and stress‐relaxation), while high‐load properties provide information on both tendon structural (eg, ultimate force and stiffness) and material (eg, ultimate stress and strain, and elastic modulus) properties.

Figure 4 Example experimental set‐up for mechanical testing of a rat Achilles tendon: (A) view from above; (B) magnified view of the muscle‐tendon‐bone complex from above; (C) side view. A muscle‐tendon‐bone complex was harvested by transecting the calcaneus and mid‐belly of the gastrocnemius‐soleus muscles. The complex was fixed to a materials testing device. The calcaneus was embedded in a fixture containing a low‐melting point alloy, while the gastrocnemius‐soleus muscles were clamped in a thermal‐electrically cooled tissue grip. The latter grip uses a thermal‐electric cooling device to cool and freeze the specimen tissue within the jaw area. The frozen tissue takes on the serpentine shape of the jaw faces, thereby preventing slippage during tensile testing of the tendon. 1 = load cell (225 N); 2 = electrical wires for thermal‐electrical cooling of the grip surfaces; 3 = circulating water that facilitates heat removal from the grips; 4 = titanium tissue grips; 5 = computer controlled actuator; 6 = serpentine grip surfaces; 7 = gastrocnemius‐soleus muscle complex; 8 = Achilles tendon; 9 = calcaneus fixed at 90° to Achilles tendon; 10 = Wood's low‐melting point alloy used to fixed the calcaneus.

Mechanical testing of animal tendons provides valuable information on tendinosis effects on tendon function. However, from a disease etiology and intervention perspective, animal models are invaluable in light of the mechanistic information they provide at the tissue and molecular levels. At the tissue level there are numerous useful techniques that can be applied in animal models which provide information on tissue structure and composition (table 2). For instance, standard histological techniques in which tissue sections are cut and stained can provide information regarding collagen fibre arrangement, cellular composition and vascularity (fig 5), while advanced histological techniques such as immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridisation are useful for the localisation of specific proteins, and DNA and RNA sequences. In addition to these techniques, tissue‐level properties of animal tendons can be determined using high‐powered electron microscopy techniques. These permit the investigation of collagen fibril arrangement and morphology (fig 6), factors that influence tendon mechanics.93

Figure 5 Histological appearance of (A) a normal tendon and (B, C) a tendon with tendinosis in an animal (rat) model. In the normal tendon (A), note the uniform appearance of tightly packed, well‐aligned collagen fibrils with interspersed tenocytes aligned parallel to the fibrils (arrow). In comparison, in the tendon with tendinosis (B) note the presence of hypercellularity, irregular collagen fibril arrangement and neovascularisation (arrows). The presence of tendinosis, as opposed to tendinitis, in this tendon was confirmed by staining for the presence of inflammatory cells. This demonstrated the presence of inflammatory cells in the paratenon (arrows), yet a complete absence of these cells intratendinously (A and B, H&E staining; C, toluidine blue staining; original magnification ×20).

Figure 6 Collagen fibril (A) arrangement and (B) morphology in the patellar tendon, as imaged using scanning and transmission electron microscopy, respectively (reprinted from Provenzano PP, Vanderby R, Jr. Collagen fibril morphology and organisation: implications for force transmission in ligament and tendon. Matrix Biol 2006;25:71–84, with permission from Elsevier).

Potential mechanisms for organ‐ and tissue‐level changes associated with tendinosis in animal models can be explored in depth using powerful molecular techniques. Tissue composition can be determined using chromatography techniques, with important features being ECM (collagens), proteoglycan (including decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin) and glycoprotein (including elastin, fibrillin, tenascin‐C) content. Meanwhile, pathways responsible for differences in tissue composition can be elucidated using a combination of microarray analyses, polymerase chain reactions (PCR), western blots, electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Microarray analysis is a powerful technology that allows simultaneous measurement of expression levels for tens of thousands of genes, permitting the molecular aspects of tendinosis pathogenesis and intervention to be modeled. However, as microarray analysis only provides information on relative expression levels, it needs to be coupled with a quantification method such as PCR. Real‐time PCR is a technique that amplifies specific reverse transcribed transcripts, allowing for their detection and quantification. While microarray analysis can indicate novel transcripts to target for quantification using PCR, it does not need to be performed if PCR transcript targets are known a priori. Since transcript levels may not be directly proportional to protein production, PCR needs to be coupled with a method for protein quantification, such as Western blots, electrophoresis or mass spectrometry. For further details on these potential outcome measures in animal tendon studies refer to Doroski et al.94

Current animal models of tendinosis

Researchers have generated and assessed tendinosis in a number of animal models using the aforementioned techniques. These have included rat models of supraspinatus and patellar tendinosis, and a rabbit model of FDP tendinosis. The models of naturally occurring tendinosis in horses and dogs will not be reviewed here as their large size and cost negates their ability to be widely used and practical animal models.

Rat model of supraspinatus tendinosis

The rat model of supraspinatus tendinosis is the most established animal model for human tendinopathy. First described by Soslowsky and colleagues,78 the model involves running rats on a treadmill at 17 m/min for 1 hr/day, 5 days/wk. Rats were chosen over 32 other laboratory animals as they had the most human‐like functional anatomy of the shoulder region (fig 1).21 The running protocol equates to a daily running distance of 1 km, which in isolation appears insufficient to overload the rodent musculoskeletal system. However, a key component of the model is the running of animals at a 10° decline. Decline running reportedly facilitated eccentric muscle contractions;78 however, its full contribution may be the relative shifting of loading from the hindlimbs to forelimbs during quadruped running. This theoretically facilitates narrowing of the subacromial space, resulting in impingement of the supraspinatus tendon. When this impingement is coupled with the approximately 7500 strides/day taken by rats during a treadmill session, it is sufficient to cause degeneration of the supraspinatus tendon.21

Tendinosis induced in the rat supraspinatus tendon has similar features to the pathological changes observed with human supraspinatus tendinopathy. Histologically, decline running in rats generates supraspinatus tendon hypercellularity and irregular collagen fibril arrangement.22,78,87 These tissue changes are coupled with mechanical decay, with running rats having reduced structural (ultimate force and stiffness) and material (ultimate stress and elastic modulus) properties.22,78,87 These changes are evident as early as four weeks following the initiation of running,22,78,87 and are exacerbated by combined introduction of an intrinsic risk factor such as collagenase injection or anatomical narrowing of the subacromial space.21,22,87 As the histological and mechanical changes induced in this model are representative of those in humans, the model has garnered acceptance as reflected by its growing use by other researchers.95,96 The utility and popularity of the model is also enhanced by its use of an extrinsic factor as the principal pathology‐inducing factor, which facilitates the translatability of findings to clinical tendinopathy.

Rat model of patellar tendinosis

A novel rat model of patellar tendinosis has recently been described by Flatow and colleagues.38,97 The model utilises the ECM theory for the generation of tendinosis and involves direct loading of the patellar tendon. The patella and tibia are gripped and distracted to apply repetitive sub‐failure loads to the patellar tendon. As controlled loading is directly applied to the tendon on an anesthetised animal, the model has the advantage of being able to generate consistent levels of tendon damage independent of other factors (such as animal compliance and muscle fatigue). Potential limitations of the model include the need for surgical exposure of the tendon for loading and the single loading bout used to induce fatigue damage. A single bout of cyclic loading is introduced until a prescribed loss of secant stiffness.98 While this has been shown to induce histological and mechanical changes consistent with those observed in humans,38,97,99 questions remain regarding whether a single bout of loading appropriately represents human tendinosis. The latter typically develops because of chronic overload and repetitive failed healing attempts.

Rabbit model of flexor digitorum profundus tendinosis

A rabbit model of FDP tendinosis at the medial elbow epicondyle has been described by Rempel and colleagues.73 Following anesthesia, the FDP muscle of one forelimb was electrically stimulated to contract repetitively for 2 h/day, 3 d/wk until reaching 80 cumulative hours of loading. Finger motion was resisted in order to facilitate loading of the FDP tendon and permit feedback about loading levels. By the end of the loading regime, cyclically loaded tendons had greater indexes of microstructural damage compared to contralateral tendons, including increased microtear area as a percent of tendon area, microtear density, and mean microtear size.73 In a subsequent study, the investigators found tendon cells increased their production of growth factors (vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, and connective tissue growth factor).100 These changes are consistent with attempted healing and may be important in tendinosis pathogenesis.

Conclusions

Animal models of tendinosis represent efficient and effective means of furthering our understanding of human tendinopathy. By selecting an appropriate species and introducing known risk factors for tendinopathy in humans, it is possible to develop tendon changes in animal models that are consistent with the human condition. Preliminary animal models are available that have achieved this; however, there is a need for much further research into these and other models. Currently available animal models of tendinosis have generated tendon histological and mechanical changes that have similar features as observed in humans, but they have been scantly described and characterised. In addition, there is a need for additional validated animal models since no single model will be able to answer all questions. Human tendinopathy occurs at multiple sites, with potentially differing pathologies, and probably as a result of multiple known and unknown risk factors. Animal models for each human scenario are desirable. For these models to be influential, they need to be conducted with careful a priori consideration to experimental design. In particular, they need to stand up to critical review. Animal studies conducted without randomisation and blinding are five times more likely to report a positive treatment effect compared to studies that use these more rigorous methods.101 Consequently, animals in tendon studies need to be randomised to groups and their samples analysed by an investigator who is blind to group allocation. Similarly, within‐animal study designs should be implemented when possible, whereby tendinosis is generated unilaterally and compared to the contralateral normal tendon. This enables tight control of genetic and environmental variables, making for statistically powerful study designs. Finally, investigators need to consider developing methods of assessing tendon pain in their animal models. Humans with tendinopathy typically present clinically with pain as their primary complaint. It is hoped that with further development of animal models of tendinosis, new strategies for the prevention and treatment of tendinopathy in humans will be generated.

What is already known on this topic

Tendinopathy is a common and significant clinical problem.

Recent histopathological studies have contributed to the understanding of the underlying pathology (tendinosis).

Little is known regarding the pathophysiology of tendinosis.

What this study adds

This study reviews the potential role of animal models in the understanding of tendinopathy.

Potential methods for inducing tendinosis in animal models are discussed and outcome measures to assess the induced changes are overviewed.

Research design considerations for the development of animal models of tendinosis are summarised.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dr Keith W Condon and Lauren J Waugh for assistance with tendon processing for Figure 3.

Abbreviations

MRI - magnetic resolution imaging

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Funding: Support for this article was provided by a Research Support Funds Grant from the Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education.

References

- 1.Lian Ø B, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Prevalence of jumper's knee among elite athletes from different sports: a cross‐sectional study. Am J Sports Med 200533561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan K M, Cook J L, Bonar F.et al Histopathology of common tendinopathies: update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med 199927393–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan K M, Bonar F, Desmond P M.et al Patellar tendinosis (jumper's knee): findings at histopathologic examination, US, and MR imaging. Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group. Radiology 1996200821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Movin T, Gad A, Reinholt F P.et al Tendon pathology in long‐standing achillodynia. Biopsy findings in 40 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 199768170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley G P, Goddard M J, Hazleman B L. Histopathological assessment and pathological significance of matrix degeneration in supraspinatus tendons. Rheumatology 200140229–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook J L, Khan K M. What is the most appropriate treatment for patellar tendinopathy? Br J Sports Med 200135291–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous The importance of animals in biomedical and behavioral research (a statement from the Public Health Service). Physiologist 199437107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Movin T, Guntner P, Gad A.et al Ultrasonography‐guided percutaneous core biopsy in Achilles tendon disorder. Scand J Med Sci Sports 19977244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kannus P, Jozsa L. Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1991731507–1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alfredson H, Forsgren S, Thorsen K.et alIn vivo microdialysis and immunohistochemical analyses of tendon tissue demonstrated high amounts of free glutamate and glutamate NMDAR1 receptors, but no signs of inflammation, in Jumper's knee. J Orthop Res 200119881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton S, Cawston T E, Riley G P.et al Human shoulder tendon biopsy samples in organ culture produce procollagenase and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases. Ann Rheum Dis 199554571–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manske P R, Lesker P A, Gelberman R H.et al Intrinsic restoration of the flexor tendon surface in the nonhuman primate. J Hand Surg [Am] 198510632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer D I, Morrison W A, Gumley G J.et al Comparative study of vascularized and nonvascularized tendon grafts for reconstruction of flexor tendons in zone 2: an experimental study in primates. J Hand Surg [Am] 19891455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlgren L A, van der Meulen M C, Bertram J E.et al Insulin‐like growth factor‐I improves cellular and molecular aspects of healing in a collagenase‐induced model of flexor tendinitis. J Orthop Res 200220910–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams I F, McCullagh K G, Goodship A E.et al Studies on the pathogenesis of equine tendonitis following collagenase injury. Res Vet Sci 198436326–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fealy S, Rodeo S A, MacGillivray J D.et al Biomechanical evaluation of the relation between number of suture anchors and strength of the bone‐tendon interface in a goat rotator cuff model. Arthroscopy 200622595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen M S, Turner T M, Urban R M. Effects of implant material and plate design on tendon function and morphology. Clin Orthop 200644581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shakibaei M, de Souza P, van Sickle D.et al Biochemical changes in Achilles tendon from juvenile dogs after treatment with ciprofloxacin or feeding a magnesium‐deficient diet. Arch Toxicol 200175369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juncosa‐Melvin N, Boivin G P, Gooch C.et al The effect of autologous mesenchymal stem cells on the biomechanics and histology of gel‐collagen sponge constructs used for rabbit patellar tendon repair. Tissue Eng 200612369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi M, Itoi E, Minagawa H.et al Expression of growth factors in the early phase of supraspinatus tendon healing in rabbits. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 200615371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soslowsky L J, Carpenter J E, DeBano C M.et al Development and use of an animal model for investigations on rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 19965383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soslowsky L J, Thomopoulos S, Esmail A.et al Rotator cuff tendinosis in an animal model: role of extrinsic and overuse factors. Ann Biomed Eng 2002301057–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmes D, Spiegel H U, Schneider T O.et al Achilles tendon healing: long‐term biomechanical effects of postoperative mobilization and immobilization in a new mouse model. J Orthop Res 200220939–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zantop T, Gilbert T W, Yoder M C.et al Extracellular matrix scaffolds are repopulated by bone marrow‐derived cells in a mouse model of Achilles tendon reconstruction. J Orthop Res 2006241299–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fransson B A, Gavin P R, Lahmers K K. Supraspinatus tendinosis associated with biceps brachii tendon displacement in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227: 1429–33, 1416 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Kasashima Y, Takahashi T, Smith R K.et al Prevalence of superficial digital flexor tendonitis and suspensory desmitis in Japanese Thoroughbred flat racehorses in 1999. Equine Vet J 200436346–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox R R. The rabbit as a research subject. Physiologist 198427393–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lander E S, Linton L M, Birren B.et al Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001409860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venter J C, Adams M D, Myers E W.et al The sequence of the human genome. Science 20012911304–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waterston R H, Lindblad‐Toh K, Birney E.et al Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 2002420520–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibbs R A, Weinstock G M, Metzker M L.et al Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution. Nature 2004428493–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbott A. Laboratory animals: the Renaissance rat. Nature 2004428464–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin T W, Cardenas L, Glaser D L.et al Tendon healing in interleukin‐4 and interleukin‐6 knockout mice. J Biomech 20063961–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mikic B, Bierwert L, Tsou D. Achilles tendon characterization in GDF‐7 deficient mice. J Orthop Res 200624831–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez A V, Perrine M, Brainard N.et al Scleraxis (Scx) directs lacZ expression in tendon of transgenic mice. Mech Dev 20031201153–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson P S, Lin T W, Reynolds P R.et al Strain‐rate sensitive mechanical properties of tendon fascicles from mice with genetically engineered alterations in collagen and decorin. J Biomech Eng 2004126252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia W, Wang Y, Appleyard R C.et al Spontaneous recovery of injured Achilles tendon in inducible nitric oxide synthase gene knockout mice. Inflamm Res 20065540–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee H, Wang V M, Laudier D M.et al A novel in vivo model of tendon fatigue damage accumulation. Trans Orthop Res Soc 2006311058 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fu S C, Wang W, Pau H M.et al Increased expression of transforming growth factor‐beta1 in patellar tendinosis. Clin Orthop 2002174–183. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Maffulli N, Testa V, Capasso G.et al Similar histopathological picture in males with Achilles and patellar tendinopathy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004361470–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu J S, Popp J E, Kaeding C C.et al Correlation of MR imaging and pathologic findings in athletes undergoing surgery for chronic patellar tendinitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995165115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rees J D, Wilson A M, Wolman R L. Current concepts in the management of tendon disorders. Rheumatology 200645508–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rolf C G, Fu B S, Pau A.et al Increased cell proliferation and associated expression of PDGFRbeta causing hypercellularity in patellar tendinosis. Rheumatology 200140256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popp J E, Yu J S, Kaeding C C. Recalcitrant patellar tendinitis. Magnetic resonance imaging, histologic evaluation, and surgical treatment. Am J Sports Med 199725218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griffiths G P, Selesnick F H. Operative treatment and arthroscopic findings in chronic patellar tendinitis. Arthroscopy 199814836–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraushaar B S, Nirschl R P. Tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow). Clinical features and findings of histological, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopy studies. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 199981259–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cook J L, Feller J A, Bonar S F.et al Abnormal tenocyte morphology is more prevalent than collagen disruption in asymptomatic athletes' patellar tendons. J Orthop Res 200422334–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matthews T J, Hand G C, Rees J L.et al Pathology of the torn rotator cuff tendon. Reduction in potential for repair as tear size increases. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 200688489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg J M, Whitaker J H. Bilateral infrapatellar tendon rupture in a patient with jumper's knee. Am J Sports Med 19911994–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cetti R, Junge J, Vyberg M. Spontaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon is preceded by widespread and bilateral tendon damage and ipsilateral inflammation: a clinical and histopathologic study of 60 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 20037478–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maffulli N, Barrass V, Ewen S W. Light microscopic histology of Achilles tendon ruptures. A comparison with unruptured tendons. Am J Sports Med 200028857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tallon C, Maffulli N, Ewen S W. Ruptured Achilles tendons are significantly more degenerated than tendinopathic tendons. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001331983–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riley G P. Gene expression and matrix turnover in overused and damaged tendons. Scand J Med Sci Sports 200515241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kettunen J A, Kujala U M, Kaprio J.et al Health of master track and field athletes: a 16‐year follow‐up study. Clin J Sport Med 200616142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stenlund B, Goldie I, Hagberg M.et al Shoulder tendinitis and its relation to heavy manual work and exposure to vibration. Scand J Work Environ Health 19931943–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cook J L, Kiss Z S, Khan K M.et al Anthropometry, physical performance, and ultrasound patellar tendon abnormality in elite junior basketball players: a cross‐sectional study. Br J Sports Med 200438206–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahieu N N, Witvrouw E, Stevens V.et al Intrinsic risk factors for the development of Achilles tendon overuse injury: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 200634226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mokone G G, Schwellnus M P, Noakes T D.et al The COL5A1 gene and Achilles tendon pathology. Scand J Med Sci Sports 20061619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Witvrouw E, Bellemans J, Lysens R.et al Intrinsic risk factors for the development of patellar tendinitis in an athletic population. A two‐year prospective study. Am J Sports Med 200129190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reeves N D. Adaptation of the tendon to mechanical usage. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 20066174–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frost H M. Skeletal structural adaptations to mechanical usage (SATMU): 4. Mechanical influences on intact fibrous tissues. Anat Rec 1990226433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mackley J R, Ando J, Herzyk P.et al Phenotypic responses to mechanical stress in fibroblasts from tendon, cornea and skin. Biochem J 2006396307–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scott A, Khan K M, Heer J.et al High strain mechanical loading rapidly induces tendon apoptosis: an ex vivo rat tibialis anterior model. Br J Sports Med 200539e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Z, Yang G, Khan M.et al Inflammatory response of human tendon fibroblasts to cyclic mechanical stretching. Am J Sports Med 200432435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang J H, Li Z, Yang G.et al Repetitively stretched tendon fibroblasts produce inflammatory mediators. Clin Orthop 2004243–250. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Cilli F, Khan M, Fu F.et al Prostaglandin E2 affects proliferation and collagen synthesis by human patellar tendon fibroblasts. Clin J Sport Med 200414232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuan J, Murrell G A, Trickett A.et al Overexpression of antioxidant enzyme peroxiredoxin 5 protects human tendon cells against apoptosis and loss of cellular function during oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004169337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Archambault J M, Elfervig‐Wall M K, Tsuzaki M.et al Rabbit tendon cells produce MMP‐3 in response to fluid flow without significant calcium transients. J Biomech 200235303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang T F, Perry S M, Soslowsky L J. The effect of overuse activity on Achilles tendon in an animal model: a biomechanical study. Ann Biomed Eng 200432336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Archambault J M, Hart D A, Herzog W. Response of rabbit Achilles tendon to chronic repetitive loading. Connect Tissue Res 20014213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Backman C, Boquist L, Friden J.et al Chronic Achilles paratenonitis with tendinosis: an experimental model in the rabbit. J Orthop Res 19908541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Messner K, Wei Y, Andersson B.et al Rat model of Achilles tendon disorder. A pilot study. Cells Tissues Organs 199916530–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakama L H, King K B, Abrahamsson S.et al Evidence of tendon microtears due to cyclical loading in an in vivo tendinopathy model. J Orthop Res 2005231199–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wisloff U, Helgerud J, Kemi O J.et al Intensity‐controlled treadmill running in rats: VO(2 max) and cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001280H1301–H1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Russell J C, Epling W F, Pierce D.et al Induction of voluntary prolonged running by rats. J Appl Physiol 1987632549–2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carlson K M, Wagner G C. Voluntary exercise and tail shock have differential effects on amphetamine‐induced dopaminergic toxicity in adult BALB/c mice. Behav Pharmacol 200617475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moraska A, Deak T, Spencer R L.et al Treadmill running produces both positive and negative physiological adaptations in Sprague‐Dawley rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2000279R1321–R1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Soslowsky L J, Thomopoulos S, Tun S.et al Overuse activity injures the supraspinatus tendon in an animal model: a histologic and biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000979–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marsolais D, Cote C H, Frenette J. Neutrophils and macrophages accumulate sequentially following Achilles tendon injury. J Orthop Res 2001191203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hsu R W, Hsu W H, Tai C L.et al Effect of shock‐wave therapy on patellar tendinopathy in a rabbit model. J Orthop Res 200422221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sullo A, Maffulli N, Capasso G.et al The effects of prolonged peritendinous administration of PGE1 to the rat Achilles tendon: a possible animal model of chronic Achilles tendinopathy. J Orthop Sci 20016349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khan M H, Li Z, Wang J H. Repeated exposure of tendon to prostaglandin‐E2 leads to localized tendon degeneration. Clin J Sport Med 20051527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tatari H, Kosay C, Baran O.et al Deleterious effects of local corticosteroid injections on the Achilles tendon of rats. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2001121333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stone D, Green C, Rao U.et al Cytokine‐induced tendinitis: a preliminary study in rabbits. J Orthop Res 199917168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fu S C, Chan B P, Wang W.et al Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1) in 11 patients with patellar tendinosis. Acta Orthop Scand 200273658–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wetzel B J, Nindl G, Swez J A.et al Quantitative characterization of rat tendinitis to evaluate the efficacy of therapeutic interventions. Biomed Sci Instrum 200238157–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carpenter J E, Flanagan C L, Thomopoulos S.et al The effects of overuse combined with intrinsic or extrinsic alterations in an animal model of rotator cuff tendinosis. Am J Sports Med 199826801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Foster F S, Zhang M Y, Zhou Y Q.et al A new ultrasound instrument for in vivo microimaging of mice. Ultrasound Med Biol 2002281165–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pautler R G. Mouse MRI: concepts and applications in physiology. Physiology 200419168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang Y ‐ X J, Bradley D P, Kuribayashi H.et al Some aspects of rat femorotibial joint microanatomy as demonstrated by high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Lab Anim 200640(3)288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Crevier‐Denoix N, Ruel Y, Dardillat C.et al Correlations between mean echogenicity and material properties of normal and diseased equine superficial digital flexor tendons: an in vitro segmental approach. J Biomech 2005382212–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang V M, Banack T M, Tsai C W.et al Variability in tendon and knee joint biomechanics among inbred mouse strains. J Orthop Res 2006241200–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Provenzano P P, Vanderby R., Jr Collagen fibril morphology and organization: implications for force transmission in ligament and tendon. Matrix Biol 20062571–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Doroski D M, Brink K S, Temenoff J S. Techniques for biological characterization of tissue‐engineered tendon and ligament. Biomaterials 200728187–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Molloy T, Kemp M, Wang Y.et al Microarray analysis of the tendinopathic rat supraspinatus tendon: glutamate signalling and its potential role in tendon degeneration. J Appl Physiol 20061011702–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Szomor Z L, Appleyard R C, Murrell G A. Overexpression of nitric oxide synthases in tendon overuse. J Orthop Res 20062480–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Flatow E L, Wang V M, Rajan L.et al How does tendon damage initiate? In: Woo S L‐Y, Abramowitch SD, Miura K, eds. International Symposium on Ligaments and Tendons ‐ V. Washington, DC,200512

- 98.Flatow E L, Nasser P, Lee L.et al Overestimation of the degradation state in fatigue loaded tendon due to transient effects. Trans Orthop Res Soc 200227621 [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang V M, Laudier D, Tsai C W.et al Imaging normal and damaged tendons: development and application of novel tissue processing techniques. Trans Orthop Res Soc 200530321 [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nakama L H, King K B, Abrahamsson S.et al VEGF, VEGFR‐1, and CTGF cell densities in tendon are increased with cyclical loading: An in vivo tendinopathy model. J Orthop Res 200624393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bebarta V, Luyten D, Heard K. Emergency medicine animal research: does use of randomization and blinding affect the results? Acad Emerg Med 200310684–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]