Abstract

Wide variations in the definitions and methodologies used for studies of injuries in rugby union have created inconsistencies in reported data and made interstudy comparisons of results difficult. The International Rugby Board established a Rugby Injury Consensus Group (RICG) to reach an agreement on the appropriate definitions and methodologies to standardise the recording of injuries and reporting of studies in rugby union. The RICG reviewed the consensus definitions and methodologies previously published for football (soccer) at a meeting in Dublin in order to assess their suitability for and application to rugby union. Following this meeting, iterative draft statements were prepared and circulated to members of the RICG for comment; a follow‐up meeting was arranged in Dublin, at which time all definitions and procedures were finalised. At this stage, all authors confirmed their agreement with the consensus statement. The agreed document was presented to and approved by the International Rugby Board Council. Agreement was reached on definitions for injury, recurrent injury, non‐fatal catastrophic injury, and training and match exposures, together with criteria for classifying injuries in terms of severity, location, type, diagnosis and causation. The definitions and methodology presented in this consensus statement for rugby union are similar to those proposed for football. Adoption of the proposals presented in this consensus statement should ensure that more consistent and comparable results will be obtained from studies of injuries within rugby union.

Wide variations in the definitions and methodologies used for investigations of injuries in rugby union have created inconsistencies in reported data, which has in turn limited the value of individual studies and severely restricted opportunities for making interstudy comparisons of results. Recent consensus statements on injury definitions and procedures for cricket1 and football2 have demonstrated an international recognition of the benefits that are gained from the use of common definitions and methodologies. The aim of this consensus statement is to establish operational definitions and methodologies for studies of injuries in rugby union.

Method

A preliminary review of the consensus statement produced for cricket1 identified that these proposals were cricket‐specific and would not translate readily to rugby union. The consensus statement from football,2 on the other hand, showed similarities to definitions and methodologies previously used in peer‐reviewed publications of studies of rugby union injuries. The International Rugby Board (IRB) Medical Advisory Committee, therefore, established a Rugby Injury Consensus Group (RICG) in order to make a detailed assessment of the methodology proposed for football and to determine whether these proposals could be adopted in rugby union, and, if this was not possible, to develop proposals that were appropriate for rugby union.

The RICG comprised seven voting members—namely, the Chief Medical Officer of the IRB, who acted as group chairman, and representatives of six national rugby unions (three from the northern and three from the southern hemisphere). Six non‐voting members with experience in the study of injuries in a range of team sports were co‐opted on to the group to provide a wider perspective and a greater understanding of the issues involved. Before the initial meeting in Dublin, each member of the RICG was provided with a copy of the football consensus statement2 to ensure that they were familiar with the issues to be discussed. The recommendations proposed by Fink et al3 for consensus group working were adopted during a 12 h meeting. Each definition and methodological issue presented in the football consensus statement was introduced and discussed by the group. Depending on the outcome from these discussions, it was proposed that either the recommendation from the football consensus group should be accepted or alternative options should be presented for consideration. After this meeting, iterative draft consensus statements were prepared and each circulated to members of the group for comment. A follow‐up meeting was held in Dublin to finalise the definitions and procedures presented in this statement. At this stage, all authors confirmed their agreement with the definitions and procedures presented in this consensus statement. The agreed document was finally presented to and approved by the International Rugby Board Council.

Discussion

The RICG endorsed the overall philosophy and broadly agreed the detail of the consensus statement presented for football,2 but, owing to the inherent differences between the games of rugby union and football, it was considered that some changes were required. For clarity, definitions are presented here in the context of rugby union; however, it was not considered necessary to re‐present comments on issues where there was agreement with the football statement. Therefore, unless specifically stated to the contrary, it should be assumed that the methods and explanatory notes contained in the football consensus statement form an integral part of this consensus statement for rugby union. The following discussion focuses on those issues where the consensus statement for rugby union departs from the statement presented for football. For comparability and ease of cross‐referencing between the two documents, the issues are presented and discussed in the same order as that used in the football consensus statement.2

Definitions

Definitions of injury can be broadly categorised into theoretical and operational definitions4: in studies of sports injuries, definitions are normally intended to provide pragmatic or operational criteria for recording cases rather than to provide a theoretical definition of injury. Although there is no generally accepted theoretical definition of an injury because of its dependence on context,4 definitions are broadly based around the concept of “bodily damage caused by a transfer or absence of energy”. This general concept may be helpful in clarifying whether an incident in rugby should be recorded as an injury.

Injury

The following definition of “injury” was accepted:

Any physical complaint, which was caused by a transfer of energy that exceeded the body's ability to maintain its structural and/or functional integrity, that was sustained by a player during a rugby match or rugby training, irrespective of the need for medical attention or time‐loss from rugby activities. An injury that results in a player receiving medical attention is referred to as a ‘medical‐attention' injury and an injury that results in a player being unable to take a full part in future rugby training or match play as a ‘time‐loss' injury.

In rugby union, non‐fatal catastrophic injuries are of particular interest and therefore a third subgroup of reportable injuries was added:

A brain or spinal cord injury that results in permanent (>12 months) severe functional disability is referred to as a ‘non‐fatal catastrophic injury'.

Severe functional disability is defined by the World Health Organization5 as a loss of >50% of the capability of the structure.

Recurrent injury

The following definition of recurrent injury was accepted:

An injury of the same type and at the same site as an index injury and which occurs after a player's return to full participation from the index injury. A recurrent injury occurring within 2 months of a player's return to full participation is referred to as an ‘early recurrence'; one occurring 2 to 12 months after a player's return to full participation as a ‘late recurrence'; and one occurring more than 12 months after a player's return to full participation as a ‘delayed recurrence'.

In rugby union studies, however, a sutured laceration that is reopened during a match or training session should be considered to be a recurrence.

Injury severity

Time (days) lost from competition and practice was accepted as the basis for defining injury severity:

The number of days that have elapsed from the date of injury to the date of the player's return to full participation in team training and availability for match selection

Injuries should be grouped, therefore, as slight (0–1 days), minimal (2–3 days), mild (4–7 days), moderate (8–28 days), severe (>28 days), “career‐ending” and “non‐fatal catastrophic injuries”.

Match exposure

The following definition of match exposure was accepted:

Play between teams from different clubs.

However, in rugby union, it is a common practice for clubs and countries to use competitive matches between A and B teams as trials for selection purposes. In these cases, A and B trial teams should be treated as though they were separate clubs and, in the case of fully‐refereed competitive trial matches between these teams, the exposure should be recorded as match exposure.

Training exposure

The following definition of training exposure was accepted:

Team‐based and individual physical activities under the control or guidance of the team's coaching or fitness staff that are aimed at maintaining or improving players' rugby skills or physical condition.

Methodological issues

The proposal that injury surveillance studies should, wherever possible, be prospective cohort studies was endorsed. In practical terms, most injury surveillance studies in rugby union will record time‐loss and non‐fatal catastrophic injuries. Because of the physical nature of rugby union and the high number of slight contusions routinely encountered in the game, studies in rugby union will normally record injuries as time‐loss injuries only if they result in more than one day of absence from training and/or matches. The nature of the game of rugby union means that recording injuries will often be more complex than is the case for football—for example, multiple injury diagnoses from a single event and multiple events (with or without multiple diagnoses) involving the same player in the same game are more common in rugby union.

Interpretation of injury definition

Studies should not incorporate mixed definitions of injury; it is anticipated that most studies on rugby union will record time‐loss injuries. A blood injury that requires a player to leave the field of play for treatment under Law 3.11(a) should not be included as an injury in a study unless the player subsequently loses time from training or competition as a result of the injury. If, however, the purpose of a study is to record the incidence of blood injuries, then these injuries should be recorded and reported separately from time‐loss injuries. Table 1 presents examples of how specific incidents should be recorded using the medical attention and time‐loss (>1‐day severity) regimens.

Table 1 Examples of how to record injuries under a “time‐loss” recording regimen.

| Example | Injury recording regimen | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time‐loss (>1 day) | Medical attention | ||

| 1. | A hooker sustained an abrasion on the thigh during a ruck. The team doctor cleaned and dressed the injury after the match. The player missed one day of training | This episode should not be recorded as an injury | This episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 1 day (slight) |

| 2. | A flanker sustained a lumbar disc injury during weight training and required 25 days rehabilitation before he could return to full training and competition | This episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 25 days (moderate) | This episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 25 days (moderate) |

| 3. | A winger sustained a hamstring injury during a training session and required 18 days of rehabilitation before he could return to full training and competition. The player sustained a further hamstring injury to the same muscle in the same leg 3 weeks later during a match. The second injury required 40 days of treatment and rehabilitation | The first episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 18 days (moderate); the second episode as a recurrence (early), severity: 40 days (severe) | The first episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 18 days (moderate); the second episode as a recurrence (early), severity: 40 days (severe) |

| 4. | A loose‐head prop forward sustained a laceration to his head during a match; the player left the field of play to enable the team doctor to suture and protect the injury. The player returned to the field of play. The player continued to train and play with his head bandaged for the next 3 weeks. | This episode should not be recorded as an injury | This episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 0 days (slight) |

| 5. | A fly‐half tackled an opposing flank‐forward during a match and sustained a dislocated shoulder. The player was unable to play again that season and failed to return to full training the following season. The player retired from playing rugby union before returning to full fitness | This episode should be recorded, severity: career‐ending | This episode should be recorded, severity: career‐ending |

| 6. | A centre suffered a minor ankle ligament injury in a match and was substituted. The player rested the next day under instruction from the team physician and returned to full training on the following day. The player subsequently sustained an injury to the same ankle ligament 7 days later during the next match. She required 35 days of treatment and rehabilitation before returning to full training | The first episode should not be recorded as an injury; the second episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 35 days (severe) | The first episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 1 day (slight); the second episode should be recorded as a recurrence (early), severity: 35 days (severe) |

| 7. | A scrum half sustained a thigh haematoma on Saturday during a match; as a result of the injury, the player would not have been able to take part in training. However, the next training session did not take place until the following Thursday, by which time the player had recovered and was able to take a full part in training activities. | The episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 4 days (mild) | The episode should be recorded as an injury, severity: 4 days (mild) |

Non‐fatal catastrophic injuries (permanent severe functional disability) should not include injuries resulting in transient neurological deficits such as burners/stingers, paraesthesias, transient quadriplegia and cases of concussion where there is full recovery.

Injury classification

The requirement that injuries should be classified by location, type, body‐side and injury event was endorsed.

Location of injury

The main groupings and categories proposed were accepted, with the additional requirement that the category of thigh injury should be subdivided into anterior thigh and posterior thigh injuries.

Type of injury

The categories proposed for reporting the type of injury sustained were broadly accepted. However, the headings used for the main groupings were subject to slight change and additional categories within these groupings were added to reflect the injury profile in rugby union—namely, injuries to the head, spinal cord and internal organs. Table 2 shows the full list of main groupings and categories that should be used in rugby union.

Table 2 Main groupings and categories for classifying the type of injury.

| Main grouping | Category |

|---|---|

| Bone | Fracture |

| Other bone injuries | |

| Joint (non‐bone) and ligament | Dislocation/subluxation |

| Sprain/ligament injury | |

| Lesion of meniscus, cartilage or disc | |

| Muscle and tendon | Muscle rupture/tear/strain/cramps |

| Tendon injury/rupture/tendinopathy/bursitis | |

| Haematoma/contusion/bruise | |

| Skin | Abrasion |

| Laceration | |

| Brain/spinal cord/ peripheral nervous system | Concussion (with or without loss of consciousness) |

| Structural brain injury | |

| Spinal cord compression/transection | |

| Nerve injury | |

| Other | Dental injuries |

| Visceral injuries | |

| Other injuries |

Other injury classification issues

Injuries should be classified as to whether they occurred during a match or training session, and whether they were the result of contact with another player or object or were a non‐contact injury. For injuries resulting from contact, activities should be recorded as tackling, tackled, maul, ruck, lineout, scrum, collision or other. It may also be appropriate to record whether the action causing the injury was deemed by the match referee to be a violation of the laws of the game or was deemed by the match referee or citing official to be “dangerous play” (Law 10.4).

Study population

The RICG endorsed the view that injury surveillance studies should normally include players from more than one team and should extend for a minimum period of one season, 1 year, or for the duration of a major tournament.

Implementation issues

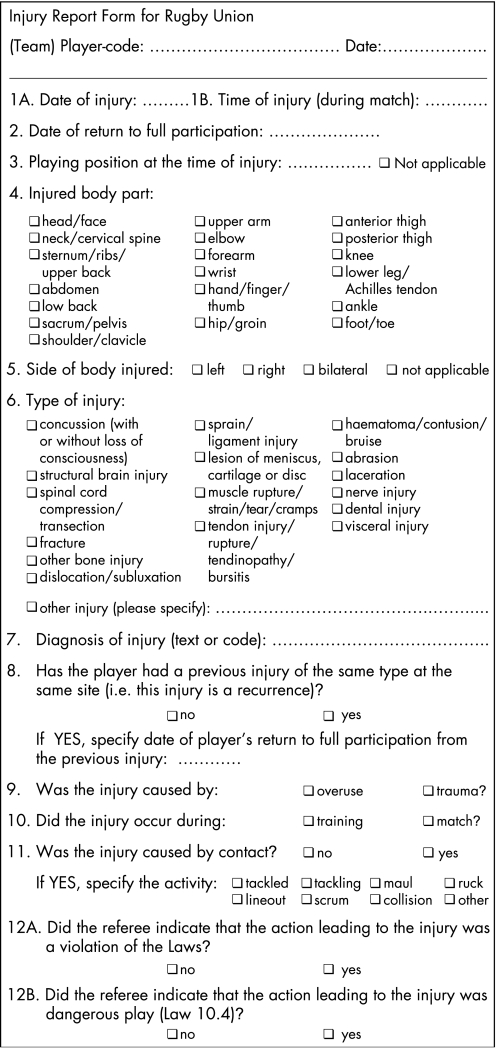

The format and content of studies should be approved by an appropriate institutional ethics committee and informed consent should be obtained from all players for their data to be included in the study. The formats of the proforma provided in the football consensus statement2 were accepted as appropriate for use in rugby union. The player's dominant arm should also be identified on the player's baseline information form, because of the importance and higher incidence of upper limb injuries in rugby union. Figure 1 provides an example of an injury form for use in rugby union.

Figure 1 An injury report form for rugby union.

For studies on rugby union that record team match exposure, the total match exposure time of players in hours for a team is given by NMPMDM/60, where NM is the number of matches played, PM is the number of players in the team (normally 15) and DM is the duration of the match in minutes (normally 80 min).

Reporting data

The RICG endorsed the view that the incidence of match and training injuries should be reported separately; in addition, injury profiles should be reported separately for match and training injuries. If the times of match injuries are recorded, the injuries should be grouped into quarters, which would normally be first half: 0–20, 21–40+; second half: 41–60, 61–80+ min. When available, the official match clock time should be used for recording the time of injury.

Conclusions

The definitions and methodology presented in the consensus statement for football were generally found to be appropriate for rugby union. Minor variations in some definitions and procedures were required, however, to reflect specific issues associated with rugby union. The definitions and procedures presented in this consensus statement should improve the quality of data collected and reported in future studies of rugby union injuries. In addition, the adoption of broadly similar definitions and methodologies across sports should enable meaningful inter‐sport comparisons of results to be made. Finally, the definitions and methodologies presented in this consensus statement will form the basis for all future studies of injuries supported by the IRB.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Orchard J W, Newman D, Stretch R.et al Methods for injury surveillance in international cricket. Br J Sports Med 200539e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuller C W, Ekstrand J, Junge A.et al Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med 200640 pp 193-201 Clin J Sports Med 200616 pp 97-106 Scand J Med Sci Sport 20061683–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M.et al Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health 198474979–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langley J, Brenner R. What is an injury? Inj Prev 20041069–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health System (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001