Infection by Penicillium marneffei is an emerging systemic illness among HIV‐infected patients. Most reports of this infection are from south‐east Asia, where this is considered as the third most common AIDS‐defining illness after tuberculosis and cryptococcosis.1 The most common initial site of infection is the reticuloendothelial system, and skin involvement is a part of disseminated infection.2 The usual cutaneous manifestations include molluscum contagiosum‐like papular eruptions involving predominantly the face and neck3; necrotic papule, pustules or nodules may also be seen.3 Inhalation of airborne conidia is the most probable mode of entry of P marneffei into the body.2 Inoculation is a rare mode of acquiring this infection, which may occur in laboratory workers. The first documented case of human infection by P marneffei was by accidental puncture of the finger of Gabriel Segretain, one of the research workers who gave the initial description of this pathogenic fungus.2 This mode of infection gives rise to nodule formation at the site of inoculation. Here, we report the unusual presentation of an HIV‐infected Indian patient with genital ulcers caused by P marneffei followed by dissemination.

A 50‐year‐old truck driver presented with genital ulcers of 2 months' duration. The lesions started on the shaft of the penis as tender nodules, which suppurated to form ulcers. In the past, he had had multiple unprotected exposures to commercial sex workers, the last being 3 months previously. Before presentation, he was known to have HIV infection for the past 3 years but was not receiving antiretroviral treatment. Earlier, he was treated for pulmonary tuberculosis, herpes zoster and herpes genitalis. At presentation, the patient was afebrile and without any constitutional symptoms. He was unwilling to divulge the details of his partner and sexual practices.

On clinical examination, the patient had oral candidiasis and generalised xerosis of skin. Examination of the genitalia revealed three closely set nodulo‐ulcerative lesions on the right anterolateral part of the shaft of the penis (fig 1). The ulcers were well defined, with a clean, moist base, without significant discharge. The most proximal ulcer was in the healing stage, showing a depressed scar. On palpation, the lesions were indurated and tender, and bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy was present. The patient was investigated with a presumptive diagnosis of sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease. Atypical mycobacterial or deep fungal infection was also considered.

Figure 1 Nodulo‐ulcerative lesions on the shaft of the penis.

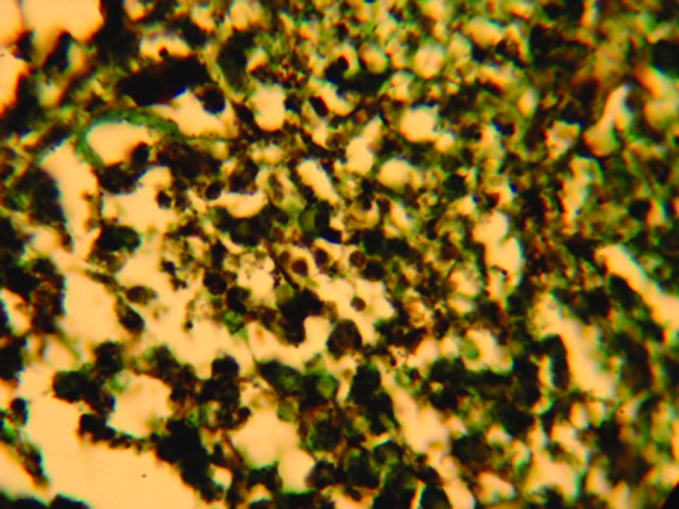

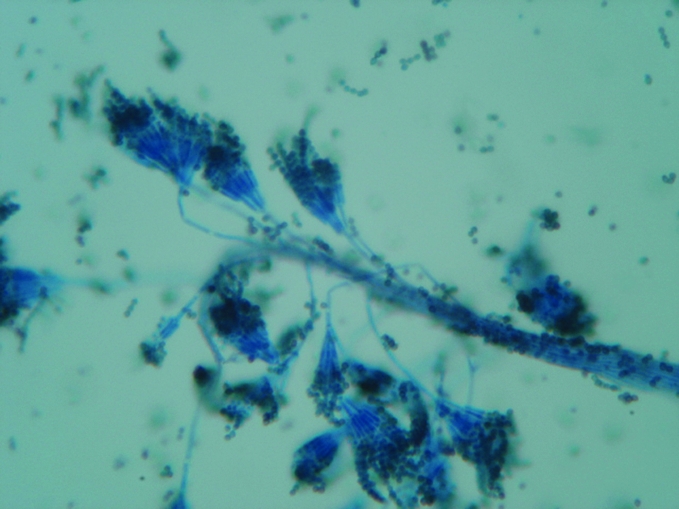

A complete haemogram revealed haemoglobin of 10 g% with a hypochromic, microcytic blood picture; erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 30 mm in the first hour. An x ray examination of the chest revealed fibrotic bands in left lower lung fields, with calcified hilar lymph nodes. He was positive for HIV‐1 antibody (western blot) and his CD4 T cell count was 369 cells/mm3. The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test was non‐reactive. Dark ground‐microscopic examination of exudate from the ulcer surface did not reveal Treponema pallidum. Smears from the surface of the ulcers were stained with Gram stain, Giemsa stain and Ziehl Neelsen stain, which did not reveal any significant organism. A biopsy was taken from one of the nodules. An H&E‐stained histopathlogical preparation showed normal epidermis and granulomatous reaction in the superficial dermis. Several intracellular and extracellular yeast‐like cells were observed intermingled with abundant eosinophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes and histiocytes. Focal areas of necrosis were present. Fite‐Faraco stain did not reveal any Mycobacteria. Gomori's methenamine silver‐stained tissue section showed intracellular, oval, yeast‐like structures (2–6 μm), with prominent central septum without budding and extracellular, elongated, slightly curved structures (8–13 μm), suggestive of P marneffei (fig 2). A smear was taken from the surface of an ulcer and cultured in Sabouraud's dextrose agar media, which grew (after 5 days of incubation at 25°C) typical colonies of P marneffei with diffusible red pigment. The characteristic morphology of the fungus was demonstrated from the culture by lactophenol cotton blue stain (fig 3). Thermal dimorphism was noted when inoculated petri dishes were incubated at 25°C and 37°C.

Figure 2 Microphotograph showing intracellular and extracellular yeast cells of Penicillium marneffei in histopathological preparation (Gomori's methenamine silver stain, magnification ×40).

Figure 3 Microphotograph showing skeleton hand/paint brush‐like clusters of phialides at the end of conidiophores (Penicillium marneffei, smear from culture, lactophenol cotton blue stain, magnification ×200).

The patient had never visited South‐East Asian countries or northeastern states of India where this fungal infection is prevalent. Repeated thorough clinical examination did not reveal any other skin lesion suggestive of disseminated P marneffei infection. There was no organomegaly. The patient's sputum and blood samples were cultured for evidence of disseminated infection with P marneffei, which could not be detected. Further investigations such as lymph node and bone marrow aspirations were suggested and antifungal treatment with itraconazole (200 mg twice daily) was advised. However, the patient was non‐compliant and lost to follow‐up. After 6 months, he was brought to casualty in a comatose state. Dermatological consultation was asked for genital lesions. History from relatives revealed that he had been unwell with fever, cough and dyspnoea for the past 2 months. For the past 10 days there had been gradual alteration of sensorium. He had not taken the treatment advised by dermatologists earlier (itraconazole). On examination, the patient was febrile, cachectic and unconscious with hypotension. Generalised lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly were present. Examination of the genitalia revealed total sloughing off of the dorsal part of the penile skin. A few non‐specific, excoriated papular eruptions were seen on the face and upper extremities. The patient died within few hours of hospitalisation. A blood count revealed neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Blood culture for fungi grew P marneffei. A retrospective diagnosis of disseminated P marneffei infection was made.

Localised skin lesions caused by P marneffei in HIV‐infected patients has not been described. This fungus causes invasive disseminated disease in this population and is almost always fatal. Chronic genital ulcer in two HIV‐infected patients with disseminated P marneffei infection has been reported.4 In the patient described here, the initial genital ulcers might have been caused by inoculation. The exact mode of inoculation could not be elicited from the history given by the patient. It is possible that the organism was inoculated to the patient's genitalia from an infected partner during sexual intercourse. Transmission may also be possible through oral sex, as oral mucosal lesions are known to occur in HIV‐infected patients with disseminated P marneffei infection.5,6 Thereafter, in the absence of treatment, dissemination might have occurred through regional lymphatics, facilitated by the immunosuppressed state of the patient.

A detailed search of the literature (available standard textbooks and Pubmed search of English publications) did not indicate the sexual route as a mode of transmission of this organism. The presentation of this HIV‐infected patient with P marneffei infection is interesting. The genital lesions caused diagnostic difficulty because it simulated traditional sexually transmitted genital ulcers. The localised lesions on genitalia without evidence of initial dissemination led us to assume that the patient might have contacted the infection by inoculation during a sexual act with an infected partner. Hence, this can be a mode of acquiring infection with P marneffei in patients with high‐risk behaviour.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Cooper C R, Jr, McGinnis M R. Pathology of Penicillium marneffei. An emerging acquired immunodeficiency syndrome‐related pathogen. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1997121798–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viviani M A, Tortorano A M. Penicillium marneffei. In: Ajello L, Hay RJ, eds. Topley & Wilson's microbiology and microbial infections. 9th edn, Vol 4. London: Arnold, 1998409–419.

- 3.Pu‐Xuan L, Wen‐Ke Z, Yan L.et al Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome associated disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection: report of 8 cases. Chin Med J 20051181395–1399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiewchanvit S, Mahanupab P, Hirunsri P.et al Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated Penicillium marneffei mycosis in five HIV‐infected patients. Mycoses 199134245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nittayananta W. Penicilliosis marneffei: another AIDS‐defining illness in Southeast Asia. Oral Dis 19995286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tong A C, Wong M, Smith N J. Penicillium marneffei infection presenting as oral ulceration in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 200159953–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]