Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

To analyze whether rapid myelosuppression and a decrease in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) induced by standard interferon (IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) combination therapy predict a sustained viral response (SVR) in hepatitis C virus patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

Data from 111 patients (mean age 48.1 years) with chronic hepatitis C virus were retrospectively analyzed. All patients were treated with the same initial doses of IFN and RBV combination therapy. The following laboratory values were measured at baseline, and then at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 of treatment: hemoglobin, white blood cells (WBCs), neutrophils, platelets and ALT. A delta value was then calculated for each interval from baseline (baseline values minus two weeks, etc). The delta value of each variable was then compared between the responders and nonresponders using Wilcoxon’s signed rank test.

RESULTS:

Sixty patients (54%) achieved an SVR. There were no significant differences between the responder and nonresponder groups for baseline variables. The delta value of ALT was the only significant marker in the prediction of an SVR. The mean ± SD delta values for the ALT at week 2 of treatment were 71±92 U/L and 44±85 U/L for the responders and nonresponders, respectively (P<0.0046). At week 4, the values were 101±96 U/L and 84±100 U/L for the responders and nonresponders, respectively (P<0.0154). The decline was then calculated for the ALT as a percentage decrease from baseline: at weeks 2 and 4, the decreases were 64% and 66%, respectively, for the responders, and 43% and 41%, respectively, for the nonresponders. At week 2, the delta values for WBC count were found to be significant in predicting failure to achieve an SVR, with mean ± SD delta values of 0.85× 109/L±1.48× 109/L and 1.53× 109/L±2.16× 109/L for the responders and nonresponders, respectively (P<0.0173). The same trend emerged at two weeks for neutrophils: 0.72× 109/L±1.33× 109/L for the responders and 1.02× 109/L±1.20× 109/L for the nonresponders (P<0.0150). The delta values were insignificant for hemoglobin, lowest hemoglobin values and platelets.

CONCLUSIONS:

The decline rates of ALT from baseline to week 2 and 4 of IFN and RBV combination therapy are good predictors of an SVR. A significant drop in WBC and neutrophil values is a predictor of failure to achieve an SVR. The hemoglobin, platelets and lowest hemoglobin values failed to predict an SVR.

Keywords: ALT, Biochemistry, Hepatitis C, Interferon, Myelosuppression, Ribavirin

Abstract

CONTEXTE ET BUT :

L’étude avait pour but d’examiner si une myélo-suppression rapide et une diminution rapide de l’alanine-aminotransférase (ALT) provoquées par la bithérapie habituelle à l’interféron (INF) et à la ribarivine (RBV) étaient un prédicteur de réponse virale prolongée (RVP) chez les patients atteints d’hépatite C.

PATIENTS ET MÉTHODE :

Nous avons procédé à une analyse rétrospective des données de 111 patients (âge moyen : 48,1 ans) atteints d’hépatite C chronique. Les patients ont tous reçu les mêmes doses initiales d’INF et de RBV en bithérapie. Les résultats de laboratoire suivants ont ensuite été mesurés au départ, puis à la 2e, 4e, 8e, 12e et 24e semaine de traitement : hémoglobine, leucocytes, neutrophiles, thrombocytes et ALT. Une valeur delta a alors été calculée pour chacun des intervalles à partir du début (valeurs de départ moins deux semaines, etc.), puis a été comparée, pour chacune des variables, entre les malades répondeurs et les malades non répondeurs à l’aide du test de Wilcoxon pour observations appariées.

RÉSULTATS :

Soixante patients (54 %) ont obtenu une RVP. Il n’y avait pas de différences significatives entre les répondeurs et les non-répondeurs en ce qui concerne les valeurs de départ. La seule valeur qui s’est révélée un marqueur prévisionnel important de RVP est la valeur delta de l’ALT. Les valeurs delta moyennes ± l’écart type pour l’ALT à la 2e semaine de traitement étaient de 71±92 U/l et de 44±85 U/l chez les répondeurs et chez les non-répondeurs respectivement (P<0,0046) et, à la 4e semaine, ces mêmes valeurs s’établissaient respectivement comme suit : 101±96 U/l et 84±100 U/l (P<0,0154). La diminution du taux d’ALT a ensuite été calculée sous forme de pourcentage à partir du début jusqu’à la 2e et à la 4e semaine, ce qui a donné des réductions de 64 % et de 66 % respectivement pour les répondeurs et de 43 % et de 41 % respectivement pour les non-répondeurs. À la 2e semaine, les valeurs delta de la numération des leucocytes se sont révélées importantes pour la prévision de l’échec de la RVP; ainsi, les valeurs delta moyennes ± l’écart type étaient de 0,85× 109/l±1,48× 109/l et de 1,53× 109/l±2,16× 109/l chez les répondeurs et chez les non-répondeurs respectivement (P<0,0173). La même tendance a été observée pour les neutrophiles à la 2e semaine : 0,72× 109/l±1,33× 109/l pour les répondeurs et 1,02× 109/l±1,20× 109/l pour les non-répondeurs (P<0,0150). Les valeurs delta concernant l’hémoglobine, les taux les plus bas d’hémoglobine et les thrombocytes n’étaient pas significatives.

CONCLUSIONS :

Le taux de réduction de l’ALT à partir du début jusqu’à la 2e et à la 4e semaine de bithérapie par l’INF et la RBV se révèle un bon prédicteurs de RVP. En revanche, une diminution importante de la valeur des leucocytes et des neutrophiles est un prédicteur de l’échec de la RVP. Enfin, les valeurs relatives à l’hémoglobine, aux thrombocytes et aux taux les plus bas d’hémoglobine n’ont pas permis de prévoir une RVP.

Human interferon (IFN) alpha-2a and 2b, in combination with ribavirin (RBV), is the current standard of care for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection worldwide. Although these drugs are usually well tolerated, many side effects have been reported. One that is of particular clinical significance is the change in hematological parameters seen during treatment, namely, anemia, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia (1).

These cytopenias are well documented effects of IFN therapy, and many mechanisms have been proposed; for example, a rapid decline in all three major cell lines (within the first 12 h to 24 h) is often explained by sequestration of platelets and white blood cells (WBCs) in the liver and spleen (2). Another suggested mechanism is the direct inhibition of progenitor cells in the bone marrow by IFN (3). Other proposed mechanisms include capillary trapping and increased apoptosis (4–6) of all cell lines. Finally, RBV itself is known to cause hemolysis, and the addition of this drug to IFN results in an additive effect on hemoglobin decline (7).

Presently, there are little data examining the relationships between the acute hematological toxicities, decreases in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and outcomes in the treatment of chronic HCV with standard IFN and RBV combination therapy. The objective of the present study was to determine whether the decline rates of these parameters are markers of therapeutic efficacy and, therefore, early markers of a sustained viral response (SVR) in HCV patients.

METHODS

Data from 111 patients with chronic HCV, who were treated between the years 1998 and 2001 at the McGill University Health Centre in Montreal, Quebec, were retrospectively analyzed. All patients were treated with a standard IFN and RBV combination therapy (standard IFN, three million units subcutaneously, three times per week; weight-dosed RBV, 1000 mg [patients less than 75 kg] or 1200 mg [patients 75 kg or more], both orally daily). Fifty-six patients underwent liver biopsy. All patients were considered for combination therapy when their ALT levels were greater than 1.5 times normal and were treated for a total of 48 weeks. At the time of data collection, genotype differentiation and viral load quantification were not used in Quebec, and were therefore not considered in the present study. A positive response was defined as an SVR at 24 weeks after the end of treatment. Additionally, standard IFN and RBV dosage adjustments for hematological toxicities were recorded, and no growth factors were used.

The data retrieved were as follows: hemoglobin, WBC, neutrophil, platelet, and ALT levels. Other WBC subpopulations (such as lymphocytes, eosinophils, etc) were not studied, because they are not typically associated with the hematotoxic profile of the treatment. These values were measured at baseline, and again at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24. The difference between the values at week 2 and baseline, week 4 and baseline, and so forth, up to the difference at week 24 and baseline were calculated; this was defined as the decline rate for each interval. Additionally, the decline rates for ALT were converted to per cent changes from the baseline measurement. The decline rates of each interval for ALT and each hematological parameter were then compared between the responders and nonresponders using Wilcoxon’s signed rank test. This statistical test was used because the studied parameters in the subject population did not follow a normal distribution.

RESULTS

The study included a total of 111 patients (68 men and 43 women), with a mean ± SD age of 48.1±10.9 years. A total of 60 patients (54%) achieved an SVR. There were no significant differences between the responder and nonresponder groups for age, sex, body mass index, degree of fibrosis (of those biopsied), baseline hematological values or ALT levels (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics of responders and nonresponders to interferon and ribavirin combination therapy (n=111)

| Demographics | Responders (n=60) | Nonresponders (n=51) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 46.7±10.9 | 49.3±10.3 |

| Male, % | 57 | 67 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.3±3.3 | 26.8±2.9 |

| Stage of fibrosis* | 2.6±1.1 | 2.7±1.1 |

| Baseline alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 122±83 | 138±98 |

| Baseline hemoglobin, g/L | 147±14 | 151±14 |

| Baseline white blood cells, × 109/L | 6.1±2.0 | 6.9±2.6 |

| Baseline neutrophils, × 109/L | 3.4±1.5 | 3.4±1.2 |

| Baseline platelets, × 109/L | 181±61 | 168±105 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. Biopsies were taken from 23 patients from the responder group and 33 patients from the nonresponder group.

*As per METAVIR scoring

No statistically significant difference in the decline rates for hemoglobin or platelets between the two groups was observed throughout the treatment duration.

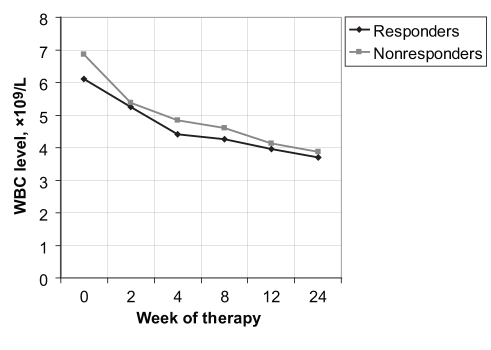

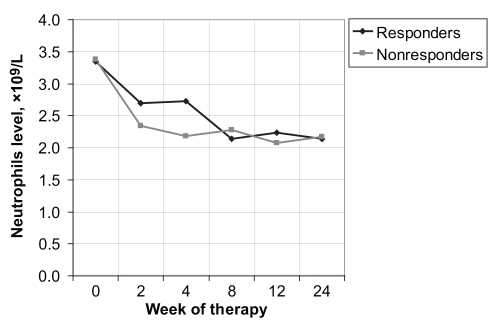

However, at week 2 of treatment, the decline rates for the WBCs were 0.85× 109/L±1.48× 109/L for the responders and 1.53× 109/L±2.16× 109/L for the nonresponders (P<0.0173) (Figure 1); for the neutrophils, the decline rates were 0.72× 109/L±1.33× 109/L for the responders and 1.02× 109/L ±1.20× 109/L for the nonresponders (P<0.0150) (Figure 2). At week 4, only the decline rates for the neutrophils were significant, with values of 0.57× 109/L±3.20× 109/L and 1.16× 109/L ±1.05× 109/L for the responders and nonresponders, respectively (P<0.035) (Table 2).

Figure 1).

White blood cell (WBC) level versus week of therapy for responders and nonresponders to interferon and ribavirin therapy

Figure 2).

Neutrophil level versus week of therapy for responders and nonresponders to interferon and ribavirin therapy

TABLE 2.

Significant decline rates of white blood cells (WBCs), neutrophils and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels during interferon and ribavirin combination therapy

| Measure | Responders (n=60) | Nonresponders (n=51) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBCs, × 109/L | |||

| Week 2 | 0.85±1.48 | 1.53±2.16 | 0.0173 |

| Week 4 | NS | NS | NS |

| Neutrophils, × 109/L | |||

| Week 2 | 0.72±1.33 | 1.02±1.20 | 0.0150 |

| Week 4 | 0.57±3.20 | 1.16±1.05 | 0.035 |

| ALT, U/L | |||

| Week 2 | 71±92 | 44±85 | 0.0046 |

| Week 4 | 101±96 | 84±100 | 0.0154 |

| ALT, % | |||

| Week 2 | 64.2 | 43.2 | 0.0003 |

| Week 4 | 65.8 | 41.3 | 0.0001 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. NS Not significant

A total of 16 patients required dose adjustments of standard IFN and RBV combination therapy to less than 80% of the expected dose because of excess hematological toxicity. There were five dose reductions in each group (responders and non-responders) due to significant neutropenia and three reductions in each group due to significant anemia. This represented approximately 13% of the responders and 16% of the nonresponders (the difference was not statistically significant).

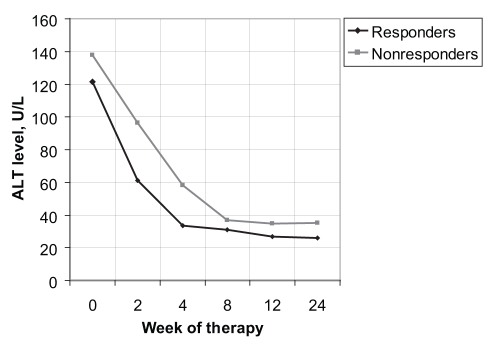

Within the first month, the decline rate that was statistically significant for the prediction of an SVR was the ALT level. At week 2, these values were 71±92 U/L and 44±85 U/L for the responders and nonresponders, respectively, (P<0.0046) (Figure 3). Calculated as a per cent decrease from baseline, this corresponded to declines of 64% and 43% for the responders and nonresponders, respectively (P<0.0003). At week 4, the decline rates were 101±96 U/L and 84±100 U/L for the responders and nonresponders, respectively (P<0.0154). As a per cent decrease from baseline, this corresponded to declines of 66% for the responders and 41% for the nonresponders (P<0.0001) (Table 2).

Figure 3).

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level versus week of therapy for responders and nonresponders to interferon and ribavirin therapy

DISCUSSION

This was a retrospective study of 111 patients with chronic HCV who were all treated with a standard IFN and RBV combination therapy for a total of 48 weeks. Our initial hypothesis was that the biological activity of the therapy, typically leading to side effects of cytopenia and decreased ALT levels, was a surrogate marker for therapeutic efficacy. Alternatively, greater hematotoxicity and larger declines in ALT were predictors of an SVR. We also theorized that larger reductions in cell lines may have contributed to the success of the therapy.

The present study demonstrated that rapid and significant declines in WBCs (within two weeks) and neutrophils (within two and four weeks) were associated with significantly lower rates of achieving an SVR. The decline rates of hemoglobin and platelets were not found to be significantly different between the responder and nonresponder groups. In our study, only 16 patients sustained dose reductions for neutropenia or anemia; these were evenly divided among responder and non-responder groups.

Our study also demonstrated a significant difference in the decline rates of the ALT level between the responder and nonresponder groups at weeks 2 and 4 of treatment. Our data suggest that a patient undergoing standard IFN and RBV combination therapy has a greater chance of achieving an SVR if the ALT declines by approximately 65% of the baseline value within two and four weeks.

Contrary to our hypothesis, our study found that rapid declines in the WBCs and neutrophils in the initial two weeks of therapy predict nonresponsiveness. Several studies have argued that when significant treatment-induced cytopenia results in dose reductions to less than 80% of either drug, this may lead to significantly lower SVR rates (8). Therefore, in such studies, poorer outcomes may have been related to inadequate dosing. Our data demonstrate that dose adjustment was equivalent in both groups, suggesting that this was probably not a factor in predicting an SVR in our population. Additionally, the average age and degree of fibrosis, determined by the METAVIR scoring system (of those biopsied), between the two groups was not different, failing to explain the difference in declining neutrophil rates within the first month. It should be noted that approximately one-half of the patients did not undergo liver biopsy.

The role of neutrophils in the elimination of HCV is unknown at the present time. It has been shown that treatment with all types of IFN and RBV results in a reduction in the absolute number of neutrophils in all treated patients (both responders and nonresponders), but does not alter neutrophil function by assays such as the C5a and formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine migration killing curves (9). In our study, there were no differences in absolute neutrophil counts between the two groups throughout the duration of therapy. This may suggest that absolute numbers of neutrophils are not important in achieving an SVR. Moreover, in a study comparing African American genotype 1 HCV patients with non-Hispanic Caucasians, a multivariate analysis showed that even significantly different baseline neutrophil values were not associated with the outcome of therapy (10). We experienced similar expected dose-related reductions in neutrophils in both groups, but our nonresponder arm experienced significantly greater decline rates within the first month of therapy. This suggests that the therapy and other factors induce a rapid change in the neutrophil population in certain individuals within the first four weeks, which ultimately lowers the chance of an SVR. From our data, it appears that neutrophil kinetics are important for the elimination of HCV. It is known that immune cells (including neutrophils) harbour HCV RNA, are replication sites for the virus and may contribute significantly to total viral load (11). We theorize that the rapid elimination of neutrophils within the first month occurs in patients with a large HCV RNA load within those neutrophils. Effectively, neutrophils may be seen as a reservoir of ‘hidden’ viral RNA in nonresponders.

In the present study, both responder and nonresponder groups sustained equivalent hemoglobin rates of decline and absolute nadir. In our study, a small but equal number of patients in both the responder and nonresponder groups sustained a dose reduction for anemia. This suggests that this parameter, in isolation, plays no role in predicting an SVR, which is consistent with the findings of other major studies (8).

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has demonstrated the relationship between a decline rate of ALT and the ability to achieve an SVR. The current standard of care when treating chronic HCV is to obtain a viral load measurement at weeks 4 and/or 12 of therapy (12), which is accepted as a good predictor of response. If ALT is regarded as a marker of total hepatocyte damage or death, then rapid decreases in ALT may theoretically reflect rapid resolution of the ongoing inflammatory state as the virus is eliminated (13,14). It has been established elsewhere that viral elimination patterns are biphasic, with the first rapid decline occurring within the first month. Our data demonstrate that larger decline rates of ALT within the first two and four weeks are predictors of an SVR. Therefore, decline rates of ALT may reflect this first phase of viral kinetics, and may be used as a strategy to help predict a response well before the four-or 12-week viral load quantification is performed.

The present study had some limitations. First, due to the abnormal distribution of hematological parameters and ALT levels of our patient population, we were obliged to use Wilcoxon’s signed rank test in the analysis. It is possible that a larger population would have permitted the application of a multivariate analysis, which would have had more statistical power. Second, at the time of data collection, viral genotyping and viral load measurements were not available. These parameters are presently known as important predictors of the outcome of HCV treatment. This precluded us from correlating these known parameters with our findings. However, the treatment dosage and duration was equal among all study subjects and, therefore, among all represented genotypes in the present study. Third, although nearly all patients had a baseline ALT level greater than 1.5 times normal, the decline rates of ALT at weeks 2 and 4 of therapy may not be applicable for those with a baseline ALT in the normal range.

To summarize the key points, when treating a patient with chronic HCV with standard IFN and RBV combination therapy, a decline in ALT of greater than 64% from baseline at weeks 2 and 4 predicts an SVR. However, a significant decline in neutrophils and WBCs after two weeks predicts a nonresponder. Hemoglobin and platelet decline rates or nadir values were not significant in predicting an SVR.

Larger studies are necessary to investigate the role of ALT decline rates in the outcome of IFN and RBV combination therapy. Further studies are needed to explore the importance of neutrophil subpopulations and kinetics on the elimination of HCV. Additionally, the role of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor as an adjunct to therapy in cases of rapid decline within the first month should be investigated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fried MW. Side effects of therapy of hepatitis C and their management. Hepatology. 2002;36(5 Suppl 1):S237–44. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dormann H, Krebs S, Muth-Selbach U, et al. Rapid onset of hematotoxic effects after interferon alpha in hepatitis C J Hepatol 2000321041–2.(Lett) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganser A, Carlo-Stella C, Greher J, Völkers B, Hoelzer D. Effect of recombinant interferons alpha and gamma on human bone marrow-derived megakaryocytic progenitor cells. Blood. 1987;70:1173–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peck-Radosavljevic M, Wichlas M, Homoncik-Kraml M, et al. Rapid suppression of hematopoiesis by standard or pegylated interferon-alpha. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:141–51. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarumi T, Sawada K, Sato N, et al. Interferon-alpha-induced apoptosis in human erythroid progenitors. Exp Hematol. 1995;23:1310–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai CH, Price JO, Brunner T, Krantz SB. Fas ligand is present in human erythroid colony-forming cells and interacts with Fas induced by interferon gamma to produce erythroid cell apoptosis. Blood. 1998;91:1235–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Franceschi L, Fattovich G, Turrini F, et al. Hemolytic anemia induced by ribavirin therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: Role of membrane oxidative damage. Hepatology. 2000;31:997–1004. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afdhal NH. Role of epoetin alfa in maintaining ribavirin dose. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2004;33(1 Suppl):S25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glue P, Rouzier-Panis R, Raffanel C, et al. A dose-ranging study of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C. The Hepatitis C Intervention Therapy Group. Hepatology. 2000;32:647–53. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conjeevaram HS, Fried MW, Jeffers LJ, et al. for the Virahep-C Study Group. Peginterferon and ribavirin treatment in African American and Caucasian American patients with hepatitis C genotype 1. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:470–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crovatto M, Pozzato G, Zorat F, et al. Peripheral blood neutrophils from hepatitis C virus-infected patients are replication sites of the virus. Haematologica. 2000;85:356–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman M, Shafran S, Burak K, et al. Management of chronic hepatitis C: Consensus guidelines. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21(Suppl C):25C–34C. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colombatto P, Civitano L, Oliveri F, et al. Sustained response to interferon-ribavirin combination therapy predicted by a model of hepatitis C virus dynamics using both HCV RNA and alanine aminotransferase. Antivir Ther. 2003;8:519–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui CK, Belaye T, Montegrande K, Wright TL. A comparison in the progression of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C between persistently normal and elevated transaminases. J Hepatol. 2003;38:511–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]