Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Canadian wait time data are available for the treatment of cancer and heart disease, as well as for joint replacement, cataract surgery and diagnostic imaging procedures. Wait times for gastroenterology consultation and procedures have not been studied, although digestive diseases pose a greater economic burden in Canada than cancer or heart disease.

METHODS:

Specialist physicians completed the practice audit if they provided digestive health care, accepted new patients and recorded referral dates. For patients seen for consultation or investigation over a one-week period, preprogrammed personal digital assistants were used to collect data including the main reason for referral, initial referral and consultation dates, procedure dates (if performed), personal and family history, and patient symptoms, signs and test results. Patient triaging, appropriateness of the referral and timeliness of care were noted.

RESULTS:

Over 10 months, 199 physicians recorded details of 5559 referrals, including 1903 visits for procedures. The distribution of total wait times (from referral to procedure) nationally was highly skewed at 91/203 days (median/75th percentile), with substantial interprovincial variation: British Columbia, 66/185 days; Alberta, 134/284 days; Ontario, 110/208 days; Quebec, 71/149 days; New Brunswick, 104/234 days; and Nova Scotia, 42/84 days. The percentage of physicians by province offering average-risk screening colonoscopy varied from 29% to 100%.

DISCUSSION:

Access to specialist gastroenterology care in Canada is limited by long wait times, which exceed clinically reasonable waits for specialist treatment. Although exhibiting some methodological limitations, this large practice audit sampling offers broadly generalized results, as well as a means to identify barriers to health care delivery and evaluate strategies to address these barriers, with the goals of expediting appropriate care for patients with digestive health disorders and ameliorating the personal and societal burdens imposed by digestive diseases.

Keywords: Access, Digestive diseases, Health care, Practice audit, Wait time

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

On connaît les données canadiennes sur les temps d’attente en matière de cancer et de maladie cardiaque, de remplacement articulaire, d’opération des cataractes et d’imagerie diagnostique. Les temps d’attente pour obtenir une consultation en gastroentérologie, puis une intervention, n’ont pas fait l’objet d’études, même si les maladies digestives représentent un plus gros fardeau économique au Canada que le cancer ou les maladies cardiaques.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les médecins spécialistes procédaient à la vérification de leur pratique s’ils dispensaient des soins en santé digestive, s’ils acceptaient des nouveaux patients et s’ils consignaient les dates des aiguillages. À l’égard des patients vus en consultation ou pour des explorations pendant une période d’une semaine, ils utilisaient un assistant numérique personnel préprogrammé pour colliger des données, y compris la principale raison de l’aiguillage, la date du premier aiguillage et de la consultation, la date de l’intervention (s’il y en avait une), les antécédents personnels et familiaux ainsi que les symptômes, signes et résultats des tests des patients. Ils consignaient également le triage des patients, la pertinence de l’aiguillage et la rapidité des soins.

RÉSULTATS :

En dix mois, 199 médecins ont consigné l’information relative à 5 559 aiguillages, y compris 1 903 visites en vue d’interventions. La répartition des temps d’attente totaux (entre l’aiguillage et l’intervention) sur la scène nationale était fortement asymétrique, avec 91/203 jours (médiane/75e percentile) et d’importantes variations inter-provinciales : Colombie-Britannique, 66/185 jours; Alberta, 134/284 jours; Ontario, 110/208 jours; Québec, 71/149 jours; Nouveau-Brunswick, 103/234 jours et Nouvelle-Écosse, 42/84 jours. Le pourcentage de médecins par province offrant des coloscopies de dépistage à risque moyen variait entre 29 % et 100 %.

DICSUSSION :

L’accès à des soins spécialisés en gastroentérologie au Canada est limité par les longs temps d’attente qui dépassent l’attente clinique raisonnable avant de recevoir un traitement par des spécialistes. Même s’il comporte certaines limites méthodologiques, ce vaste échantillon de vérification de la pratique offre des résultats très généralisés, ainsi qu’un moyen de repérer les obstacles à la prestation des soins et d’évaluer des stratégies pour les vaincre, en vue d’accélérer les soins pertinents aux patients atteints de troubles de santé digestive et de réduire les fardeaux personnels et sociétaux imposés par les maladies digestives.

Wait times for medical care have emerged as a primary focus for assessing the adequacy of health care delivery in Canada. Surveys highlighting excessive wait times (1–3) led the federal and provincial governments to establish indicators of health care access and evidence-based benchmarks for medically acceptable wait times related to cancer, heart disease, diagnostic imaging procedures, joint replacement and sight restoration (4). Although data are now available for these areas, little is known about access to health care for other conditions or the extent to which emphasis on these five key areas affects health care delivery for other conditions.

Canadian gastroenterologists and hepatologists have expressed great concern that access to care for digestive diseases is suboptimal, with reports that patients can wait longer than one year for nonurgent endoscopy. Neither the extent of these limitations nor their cause is known in detail. However, access to care may be limited by a number of factors, including a shortage of specialist gastroenterologists, and constraints on funding and resources for endoscopic investigations. The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG), therefore, instituted a three-pronged approach to evaluating human resources in digestive health care. It completed a detailed workforce analysis, including a census of digestive disease physicians in Canada (5); a consensus conference to establish target maximal wait times for gastroenterology services based on reason for referral (6); and a national study of wait times for consultation, and for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, using a practice audit methodology and real-time, point-of-care data collection (7).

The objective of the present study was to document the time from initial referral until consultation and procedures for patients with digestive diseases. Although wait times are an imprecise measure of human resource availability, they are used widely as a measure of health care availability and provide a standard measure of the adequacy of health care delivery in different situations. Real-time, point-of-care data collection techniques were used to minimize the risk of recall bias in determining wait times and to evaluate wait times in an ambulatory care setting, with more precise data on patient demographics, urgency and diagnosis than can be acquired from institutional, regional, provincial or national databases.

METHODS

A special expert committee from the CAG, with expertise in the area, was integrally involved in all aspects of the program, including concept development, practice audit logistics management, data reporting and data analysis.

Participants

Specialist physicians providing health care to patients with digestive diseases were recruited through announcements to CAG members and provincial gastroenterology organizations. Physicians were eligible to participate if their practice was open to consultations and procedures for new referrals, and if they routinely documented the date on which patients were first referred for consultation. All participants were required to obtain approval from their local ethics committee or under a group application to an independent ethics review board. The study protocol was reviewed, and standardized definitions of all recorded variables were set before commencement at an investigators’ meeting and again on delivery of the personal digital assistants (PDAs) (Compaq iPAQ 3670, Compaq, Taiwan) at the start of the audit.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed by a steering committee with expertise in gastroenterology, education, past national audit projects and software development. The PDAs were programmed (using Embedded Visual Basic 3.0, Microsoft Corporation, USA) to use only predefined list boxes and drop-down menus; individual questions and the related response choices were displayed on one screen to avoid the need for scrolling, and fields were compulsory to preclude missing data. This approach was adopted to enhance the simplicity, validity and reliability of data entry, and to facilitate subsequent analyses. After pilot testing, the questionnaire was revised and downloaded to the PDAs, which were lent for one week to participants.

Section I:

Information on participants and their practice setting was recorded before any patient data were collected (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of data collected during the Practice Audit in Gastroenterolgy (PAGE)

|

Section I: Demographic data |

| Physician demographics |

| Sex |

| Primary specialty or subspecialty |

| Years in specialist practice |

| Practice demographics |

| Province |

| Postal code |

| Location population |

| Individual or group practice |

| University or private practice |

| Endoscopy suite location |

| Local service provision |

| Type of specialists providing digestive disease consultations |

| Type of specialists providing endoscopy services |

| Provision of wait time tracking |

| Estimated wait times for routine consultation |

| Estimated wait times for routine endoscopy/colonoscopy |

| Provision of internal medicine call |

| Reserved time for emergencies |

| Provision of screening colonoscopy for average-risk patients |

| Acceptance of new referrals |

| Use of triage to prioritize referrals |

|

Section II: Patient-specific data |

| Baseline referral data |

| Specialty of referring physician |

| Date of initial referral |

| Referral mechanism (eg, fax, letter, phone call) |

| Type of visit (consultation versus procedure) |

| Date of consultation and/or procedure visit |

| Reason for visit |

| Referral for a specific test |

| Procedure performed (procedure visit only) (upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, radiological procedure, gastrointestinal function test, other) |

| Whether appointment was rescheduled |

| Whether referral was triaged |

| Patient history |

| Presence of any alarm features* |

| Symptoms and/or signs |

| Presence of abnormal test results |

| Family history of digestive diseases |

| Patient history of digestive diseases |

| Primary reason for the referral |

| Physician evaluation |

| Likelihood of cancer |

| Priority for endoscopy (if deemed necessary) |

| Medical appropriateness of referral |

| Timeliness of health care delivery |

*Alarm features include abdominal mass, dysphagia, positive occult blood test, anemia, bloody diarrhea, melena or rectal bleeding, hematemesis, vomiting, jaundice and weight loss (8)

Section II:

Participants were asked to record data on all consecutive, eligible patients seen for consultation (up to 20 questions) or a procedure (up to 22 questions) during the week-long audit (Table 1). The week of the audit was determined by chance, based on the availability of the PDAs; thus, participants did not know in advance which week would be audited. Patients were eligible if they consented to the use of personal information, if they were new patients or known patients with a new medical problem (routine reassessments and surveillance procedures were excluded), and if the precise date of the patient’s first referral (by phone call, letter or form, fax, etc) was known. Anonymized patient historical data and visit-related data were then entered into the PDAs. Prioritization of appointments was evaluated by asking participants to determine how, with the information that was available, they would have assigned an appointment using the following arbitrary definitions: emergency (same day), urgent (within seven days), intermediate (within seven weeks) and elective (within seven months).

After audit completion, PDAs were collected, and the data were downloaded to the central server/database and checked for validity, duplication and loss using an automated quality control system. Using random manual checks, central server data were validated against the original PDA data for 5% of audits to ensure data integrity.

Data analysis

Independent data analysis and statistical support was provided by the Division of Gastroenterology at McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario) (YC). Statistical analyses (SAS version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc, USA) generated three wait time durations:

The wait time to consultation: from the patient’s first referral to the digestive health care provider until the consultation;

The wait time to procedure: from the patient’s first consultation with the digestive health care provider until completion of the digestive disease procedures or tests; and

The total wait time: from the patient’s first referral to the digestive health care provider until completion of the procedures or tests.

Because wait times were not normally distributed, descriptive statistics are presented using the 25th, 50th (median) and 75th percentiles. Results by categorical variables are presented using counts, percentages and 95% CIs, which were calculated using a normal approximation of the binomial distribution. No formal statistical comparisons were performed, because this was a descriptive and hypothesis-generating, rather than a hypothesis-testing, study.

RESULTS

Participants and audits

Between January and October 2005, 199 physicians participated in the study; 187 (94%) were adult gastroenterologists, comprising approximately 34% of all practising Canadian gastroenterologists (5). The remaining physicians were hepatologists (n=6), pediatric gastroenterologists (n=2), internists (n=2) and surgeons (n=2). Participants were primarily men (n=179; 90%), with reported years in specialty practice of one to five years (n=32; 16%), six to 10 years (n=30; 15%), 11 to 20 years (n=66; 33%), 21 to 30 years (n=52; 26%) and more than 30 years (n=19; 10%). Most (85%) of the 5559 referrals were from primary care physicians; consultations alone accounted for 3656 audits (66%), and visits for procedures (including same-day consultation and procedure) accounted for the remaining 1903 (34%). More than one-half (56%) of participants tracked wait times; 86% reserved time in their schedule to handle emergency cases. The proportion of physicians offering screening colonoscopy for individuals with an average risk of developing colon cancer (age 50 or older, with no family history) per province ranged from 29% to 100% (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographics, with overall median and 25th to 75th percentile wait times, provincially and nationally

| Demographics | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | NL | National |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | 30 | 18 | 4 | 5 | 72 | 46 | 7 | 14 | 3 | 199 |

| Participants triaging their wait list, % | 90 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 54 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 84 |

| Participants offering average-risk screening colonoscopy, % | 47 | 83 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 83 | 43 | 29 | 100 | 78 |

| Wait time to consultation, days | ||||||||||

| Median | 48 | 107 | 58 | 65 | 72 | 59 | 77 | 38 | 111 | 66 |

| 25th–75th percentile | 20–94 | 35–172 | 11–152 | 29–91 | 37–118 | 23–97 | 27–196 | 13–112 | 26–167 | 28–119 |

| Audits, n | 774 | 456 | 60 | 100 | 2480 | 1096 | 226 | 290 | 77 | 5559 |

| Wait time to procedure, days | ||||||||||

| Median | 28 | 36 | 26 | 14 | 51 | 60 | 36 | 15 | 19 | 43 |

| 25th–75th percentile | 11–138 | 9–103 | 0–82 | 7–67 | 18–117 | 23–113 | 6–118 | 7–50 | 2–83 | 13–114 |

| Audits, n | 401 | 218 | 26 | 3 | 774 | 276 | 128 | 53 | 24 | 1903 |

| Total wait time, days | ||||||||||

| Median | 66 | 134 | 34 | 14 | 110 | 71 | 104 | 42 | 34 | 91 |

| 25th–75th percentile | 24–185 | 42–284 | 7–183 | 10–67 | 47–208 | 33–149 | 31–234 | 17–84 | 12–115 | 33–203 |

| Audits, n | 401 | 218 | 26 | 3 | 774 | 276 | 128 | 53 | 24 | 1903 |

AB Alberta; BC British Columbia; MB Manitoba; NB New Brunswick; NL Newfoundland; NS Nova Scotia; ON Ontario; QC Quebec; SK Saskatchewan

Overall wait times

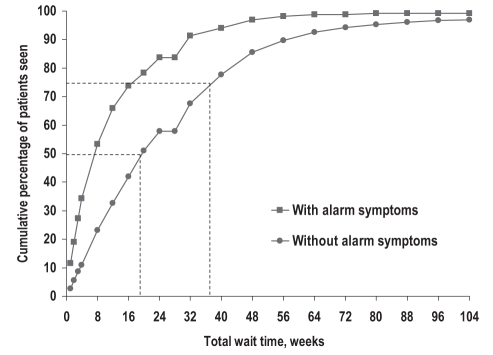

The distributions of wait times were skewed with long right tails (Figure 1). Nationally, the median wait times to consultation and to procedure were 66 days (95% CI 64 to 69 days) and 43 days (95% CI 40 to 48 days), respectively, while the median total wait time was 91 days (95% CI 84 to 99 days), although there were marked differences between provinces (Table 2).

Figure 1).

Cumulative percentage of patients seen nationally for consultation plus procedure (total wait time), with and without alarm symptoms

There were no consistent differences in wait times with respect to practice type or size of local population, and although there was some variability with respect to endoscopy suite location, there were relatively few audit data from private clinics (Table 3). Median (25th to 75th percentiles) total wait times ranged from 99 days (37 to 208 days) for physicians who offered screening colonoscopy for average-risk patients to 66 days (26 to 180 days) for physicians who did not, and from 120 days (46 to 246 days) for patients with normal test results to 58 days (18 to 149 days) for patients with abnormal test results at referral (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

National median wait times and 25th to 75th percentiles, as a function of demographics and other variables

| Variable |

Median wait time in days (25th–75th percentile), audits |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| To consultation | To procedure | Total | |

| Endoscopy suite location* | |||

| Community hospital | 73 (28–125), n=2864 | 38 (12–112), n=1013 | 98 (32–217), n=1013 |

| University or teaching hospital | 62 (25–122), n=2357 | 44 (11–109), n=855 | 84 (33–177), n=855 |

| Private clinic | 64 (41–86), n=604 | 57 (23–196), n=93 | 125 (50–263), n=93 |

| Practice type | |||

| Independent | 69 (26–119), n=3123 | 40 (12–118), n=1149 | 90 (31–215), n=1149 |

| Group | 65 (29–119), n=2436 | 48 (16–113), n=754 | 93 (36–187), n=754 |

| Location population | |||

| Less than 100,000 | 67 (27–133), n=315 | 50 (14–118), n=93 | 80 (25–206), n=93 |

| 100,000–499,999 | 70 (32–117), n=2626 | 38 (12–129), n=829 | 102 (32–234), n=829 |

| More than 499,999 | 62 (25–120), n=2618 | 47 (13–106), n=981 | 84 (35–176), n=981 |

| Screening colonoscopy for average-risk patients | |||

| Yes | 69 (30–119), n=4518 | 50 (14–118), n=1447 | 99 (37–208), n=1447 |

| No | 56 (19–119), n=1041 | 28 (8–99), n=456 | 66 (26–180), n=456 |

| Test results | |||

| Normal | 72 (29–127), n=911 | 57 (11–146), n=317 | 120 (46–246), n=317 |

| Abnormal | 50 (16–103), n=1825 | 27 (7–81), n=668 | 58 (18–149), n=668 |

| No test results | 71 (36–126), n=2852 | 53 (19–128), n=929 | 106 (42–217), n=929 |

*Multiple choices were allowed; hence, total may exceed 100%

Alarm features

The presence of one or more alarm features (Table 1) (8), noted in 40% of consultations and 45% of procedure visits, was associated with a median wait time to consultation of 43 days (95% CI 41 to 48 days), compared with 82 days (95% CI 78 to 86 days) for patients without alarm features. Overall, the median total wait time was 49 days (95% CI 42 to 56 days) for patients with at least one alarm feature, compared with 135 days (126 to 148 days) for those with none (Figure 1); differences in wait times associated with alarm features were observed in all provinces for which there were at least 45 recorded audits (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Effect of the presence of alarm features on median total wait times for provinces with at least 45 recorded audits and nationally

| Alarm features* |

Median total wait in days, 25th–75th percentile, audits |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | AB | ON | QC | NB | NS | National | |

| One or more present | 41, 20–100, n=171 | 49, 16–129, n=93 | 62, 23–133, n=316 | 46, 14–124, n=92 | 65, 22–118, n=65 | 17, 14–38, n=21 | 49, 18–119, n=781 |

| None present | 104, 33–337, n=203 | 231, 116–311, n=102 | 153, 83–261, n=372 | 90, 42–160, n=161 | 219, 97–280, n=59 | 74, 36–119, n=26 | 135, 63–262, n=943 |

*Alarm features include abdominal mass, dysphagia, positive occult blood test, anemia, bloody diarrhea, melena or rectal bleeding, hematemesis, vomiting, jaundice and weight loss (8). AB Alberta; BC British Columbia; NB New Brunswick; NS Nova Scotia; ON Ontario; QC Quebec

Patient triaging

Formal or informal wait list triaging was performed by 84% of participants. Nationally, 55% of patients were triaged; 2% were classified as emergencies (same day appointment), 10% as urgent (appointment within seven days), 23% as intermediate (appointment within seven weeks) and 21% as elective (appointment within seven months). The median (95% CI) wait times for each of these triage classes were one day (95% CI 0 to 5 days), 14 days (95% CI 12 to 17 days), 62 days (95% CI 53 to 68 days) and 203 days (95% CI 184 to 216 days), respectively.

Patient scheduling and timeliness of care

Approximately 89% (95% CI 88.2% to 89.9%) of visits occurred as originally scheduled or were delayed. In 11% of audits, patients were seen sooner than originally planned, more commonly at the physician’s request (7%, 95% CI 4.5% to 9.5%) than for other reasons (4%, 95% CI 1.4% to 6.5%).

The personal opinion of participants was that most of the patient referrals were medically appropriate (97.4%, 95% CI 97.0% to 97.8%). Nationally, 40.2% (95% CI 38.2% to 42.3%) ‘agreed strongly’ with the statement: “Taking into account all factors, I am comfortable with the timeliness of health care delivery for this patient”; 32.6% (95% CI 30.5% to 34.8%) ‘agreed somewhat’, 5.6% (95% CI 3.0% to 8.1%) were ‘undecided’, 13.8% (95% CI 11.4% to 16.3%) ‘disagreed somewhat’ and 7.8% (95% CI 5.2% to 10.3%) ‘disagreed strongly’ with the statement, based on personal opinion.

DISCUSSION

The present data represent the first systematic evaluation of Canadian wait times for patients with digestive diseases referred to practising gastroenterologists. The practice audit methodology (7) provided ‘point-of-care’ data for the times from referral to consultation and to procedure, with accompanying data on the physicians’ practice types and locations, as well as factors related to referral and prioritization. These data indicate a median total wait time for all referrals of three months, ranging from one month to longer than four months in different provinces. Patients with alarm features based on history or abnormal test results have shorter median total wait times; conversely, the median total wait time for patients who have no reported alarm features is longer than four months, with one-quarter of patients waiting nearly nine months. These results confirm anecdotal reports that access to specialist gastroenterology care is delayed throughout most of Canada; compared with the benchmark of one to three months set for the five priority areas (9), digestive care wait times are markedly prolonged, and this is also evident in comparison with national digestive health care targets (6).

For gastroenterologists, the time to procedure is generally synonymous with the time to endoscopy (upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or colonoscopy), and because of the nature of endoscopy, it is an indication of the intervals both to diagnosis and to therapy for patients managed by gastroenterology sub-specialists. The present study was not intended to provide a comprehensive measure of national wait times for all patients with potential digestive diseases but, rather, to provide a snapshot of current wait times during one-week observation periods for patients seen by practising gastroenterologists across the country. Times reported here do not reflect waits for patients who moved, received care in the emergency department, improved or were not seen by participating gastroenterologists for various other reasons. Wait times may appear to be falsely short if resource limitations deter family physicians from referring their patients to a gastroenterologist or promote referrals to nongastroenterologist specialists.

The practice audit was completed by approximately one-third of Canadian gastroenterologists (5). Although it is possible that the results may have been biased by the self-selection of physicians willing to undertake a practice audit or by limiting participants to those who documented the date of the patient’s first referral, the wait times to procedure were actually shorter than those reported in other national surveys of wait times for endoscopy and colonoscopy in 2005 (3) and 2006 (10). It is difficult to hypothesize on the representativeness of the participating physicians, because motivation to participate may have reflected an underlying bias toward a practice with prolonged wait times (and discontent with the system), or on the contrary, an interest in organizing one’s practice toward optimizing the timing of health care delivery. However, the general demographic profile of participants was in keeping with that of practising members of the CAG. Because these surveys were based on a recollection of past practice (3,10), with a response rate of less than 30% from physicians surveyed, it seems unlikely that the methodology of the present practice audit led to a major overestimation of wait times in gastroenterology. Furthermore, the provincial variations in wait times seen in the current practice audit were consistent with the variations reported in previous surveys (3,10). The reasons for these variations are not known but are probably the result of many factors, including regional differences in human and other resources, physicians’ practice patterns and job descriptions, as well as provincial policies, practices and systems (11). The current study has identified variations in wait times associated with a number of other practice-related factors, including the presence of alarm features, the reporting of prior abnormal test results, the availability of ‘average-risk’ colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer and the practice of patient prioritization or ‘triaging’. In the present study, the term ‘triage’ denoted an unspecified and disparate mechanism whereby the physician prioritized patients for urgent or nonurgent assessment based on information provided by the referring physician. The audit has highlighted aspects of practice that may be associated with delayed care as a basis for future studies to identify predictors of outcomes and to evaluate targeted interventions that may expedite care.

The use of an established, PDA-based practice audit methodology was a cornerstone of the present study (7); it permitted the standardized collection of data by specialists who had direct access to the medical history and dates of referral, consultation and procedures for each patient. The subsequent electronic data downloading and checks for completeness, validity and plausibility, described previously (7), provided data of greater accuracy, generalizability and local relevance than those available from regional or provincial administrative databases. As a practice audit, this methodology allows physicians, individually or as a group, to reflect on their own practice in comparison with national practice and identify deficiencies that may be addressed locally (7).

It is, perhaps, surprising that 40% of physicians agreed strongly that they were comfortable with the timeliness of patient care. Participants may have framed their responses from the perspective of a constrained health care system rather than from the perspective of the individual patient’s well-being. More importantly, timeliness of care was assessed after the patient had been seen; the evaluation may, therefore, have been biased by the knowledge that these specific patients had not suffered major sequelae as a result of a prolonged wait. Despite this, nearly 60% of participating physicians reported some reservations regarding the timeliness of patient care.

Wait times represent a single composite measure of several aspects of health care delivery and are influenced by many factors. As a result, interventions that are intended to improve access to care may prove to have a paradoxical effect. For example, the provision of increased financial resources for colorectal cancer screening may reduce the number of physicians, and thus, access to care, in other areas; provision of increased physician resources may prolong wait times if primary care physicians then refer patients for whom they would not previously have requested a specialist’s opinion.

Digestive diseases impose a greater economic burden in Canada than any other disorder, including cancer and cardiovascular disease (12). Delivery of appropriate, timely care requires recognition of this burden; therefore, it is crucial that digestive health care be considered in provincial and federal government initiatives to improve access, reduce wait times and establish patient guarantees.

CONCLUSIONS

The present practice audit has confirmed that wait times for access to specialist gastroenterology care are prolonged across Canada, and has provided baseline data on wait time variations that may reflect important differences in practice and regional policies. More importantly, the study has confirmed the applicability of PDA-based practice audits for real-time, point-of-care acquisition of wait time data, providing a basis for future studies to identify barriers to timely care, to devise strategies to overcome these barriers and to evaluate the effect of strategies on patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of all who participated in the PAGE Wait Times Program, including members of the CAG. Isis Digital Media Inc developed the software, maintained the Web site and database, and provided technological support and service. This educational initiative was funded by the CAG and by an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca Canada Inc. The authors would like to thank the representatives of AstraZeneca Canada Inc for their assistance in distributing the PDAs to reduce study costs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanmartin C, Ng E, Blackwell D, Gentleman J, Martinez M, Simile C, for the Health Analysis and Measurement Group. Statistics Canada. for the National Center for Health Statistics Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, United States. Joint Canada/United States survey of health, 2002–03<http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/82M0022XIE/2003001/pdf/82M0022XIE2003001.pdf> (Version current at January 15, 2008).

- 2.Sanmartin C, Gendron F, Berthelot J-M, Murphy K, for the Health Analysis and Measurement Group. Statistics Canada Access to health care services in Canada, 2003 <http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/82-575-XIE/2003001/pdf/report.pdf> (Version current at January 15, 2008).

- 3.Esmail N, Walker MA, for the Fraser Institute Waiting your turn: Hospital waiting lists in Canada 15th ednOctober2005. <http://www.fraserinstitute.org/researchandpublications/researchtopics/hospitalwaitinglists.htm> (Version current at January 15, 2008).

- 4.Health Canada A 10-year plan to strengthen health care September162004. <http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/delivery-prestation/fptcollab/2004-fmm-rpm/nr-cp_9_16_2_e.html> (Version current at January 15, 2008).

- 5.Moayyedi P, Tepper J, Hilsden R, Rabeneck L. International comparisons of manpower in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:478–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paterson WG, Depew W, Paré P, et al. for the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Wait Time Consensus Group. Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:411–23. doi: 10.1155/2006/343686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong D, Hollingworth R, Gardiner T, et al. Practice Audit in Gastroenterology (PAGE) program: A novel approach to continuing professional development. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:405–10. doi: 10.1155/2006/685960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Flook N, Chiba N, et al. An evidence-based approach to the management of uninvestigated dyspepsia in the era of Helicobacter pyloriCanadian Dyspepsia Working GroupCMAJ 200016212 SupplS3–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Medical Association Wait Time Alliance for Timely Access to Health Care. It’s about time! Achieving benchmarks and best practices in wait time management: Final report by the Wait Time Alliance for Timely Access to Health Care, August 2005. <http://www.cma.ca/multimedia/CMA/Content_Images/Inside_cma/Media_Release/pdf/2005/wta-final.pdf> (Version current at January 15, 2008).

- 10.Esmail N, Walker MA, for the Fraser Institute Waiting your Turn: Hospital Waiting Lists in Canada 16th ednOctober2006. <http://www.fraserinstitute.ca/admin/books/chapterfiles/wyt2006.pdf#> (Version current at January 15, 2008)

- 11.Kondro W, Hébert PC.They deserved better CMAJ 20071761557(Edit) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck IT. Disproportion of economic impact, research achievements and research support in digestive diseases in Canada. Clin Invest Med. 2001;24:12–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]