Abstract

Inappropriate functioning of the immune system is linked to immune deficiency, autoimmune disease, and cancer. It is therefore not surprising that intracellular immune signaling pathways are tightly controlled. One of the best studied transcription factors in immune signaling is NF-κB, which is activated by multiple receptors and regulates the expression of a wide variety of proteins that control innate and adaptive immunity. A20 is an early NF-κB-responsive gene that encodes a ubiquitin-editing protein that is involved in the negative feedback regulation of NF-κB signaling. Here, we discuss the mechanism of action of A20 and its role in the regulation of inflammation and immunity.

A20 (also known as TNFAIP3) was originally identified as a TNF2-inducible gene in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (1). Subsequent research demonstrated that A20 is also induced in many other cell types and by a wide range of other stimuli (reviewed in Ref. 2). Although A20 was originally characterized as an inhibitor of TNF-induced apoptosis (3), it has been most intensively studied as an inhibitor of NF-κB activation. NF-κB is a dimeric transcription factor that plays a key role in inflammation and immunity. A deregulated NF-κB response has been associated with several autoimmune diseases and some cancers (4). The activity of NF-κB is tightly regulated by interaction with inhibitory IκB (inhibitor of κB) proteins, which are regulated by IKK-mediated IκB phosphorylation, followed by their ubiquitination and proteolysis, enabling the entry of NF-κB into the nucleus. In most cases, the activation of NF-κB is transient and cyclic upon continuous stimulation, which is due to specific negative feedback control systems such as the NF-κB-inducible synthesis of IκB and A20 proteins (5). NF-κB activation pathways are broadly classified as either canonical or non-canonical, depending on whether activation involves IκB degradation or processing of the p100 NF-κB precursor (4). The canonical pathway, which is the predominant NF-κB signaling pathway, is activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IL-1 and microbial components that activate, for example, TLRs or antigen receptors. The non-canonical pathway of NF-κB activation operates mainly in B cells in response to a subset of TNFR family members, including the lymphotoxin-β receptor.

Initial evidence for the NF-κB inhibitory function of A20 came from several studies in which overexpression of A20 was shown to prevent NF-κB activation in response to TNF and several other pro-inflammatory stimuli (reviewed in Ref. 2). The observation that A20 expression is itself under the control of NF-κB suggested its involvement in the negative feedback regulation of NF-κB activation (6). This was eventually confirmed by the generation of A20-deficient mice, which show a sustained NF-κB response and severe inflammation (7). The mechanism by which A20 inhibits NF-κB activation remained a mystery for several years until it was recently found that A20 can act as a dual ubiquitin-editing enzyme.

Inhibitory Effect of A20 on Pro-inflammatory Gene Expression

The use of A20-deficient mice and RNA interference technologies has revealed the crucial role of A20 in a variety of pathogen- and cytokine-induced signaling pathways. Mice lacking A20 are born at normal mendelian ratios but die shortly after birth due to massive multiorgan inflammation, indicative of a key role for A20 in immune homeostasis of the host (7). A20-deficient MEFs and thymocytes exhibit a prolonged activation of NF-κB after administration of TNF. However, the cachexia and wasting in A20-deficient mice could not be fully attributed to overactivation of TNF signaling because a multi-inflammatory phenotype and premature death were also observed in double A20/TNF-deficient mice. Bone marrow transfer of A20-deficient hematopoietic cells into a wild-type background gives a similar phenotype as the total knock-out, whereas absence of lymphocytes in double A20/RAG1-deficient mice does not ameliorate the phenotype (7, 8). These findings suggest a crucial role for macrophages in the phenotype of A20 knock-out mice. It was demonstrated recently that the spontaneous inflammation in A20-deficient mice can be mainly assigned to TLR signaling because mice double deficient for A20 and the TLR adaptor protein MyD88 no longer show premature lethality and cachexia (8). This is consistent with the previous finding that TLR-induced A20 is essential for the termination of TLR-induced NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in macrophages and the prevention of LPS-induced shock (9). Antibiotic treatment also ameliorates the hyperinflammatory response in A20-deficient animals, which is consistent with an important role of TLR signaling initiated by commensal bacteria (8).

Although A20 deficiency has a clear detrimental effect on immunity, abrogating the immunosuppressive function of A20 in myeloid cells was recently exploited in an attempt to increase the response of T cells in anti-tumor vaccination. A20 knockdown in dendritic cells results in enhanced expression of specific co-stimulatory signals as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines, causing a shift in the subset of activated T cells. Both cytotoxic T cells and T helper cells were hyperactivated, whereas regulatory T cells were markedly suppressed, with beneficial anti-tumor effects as a result (10).

A20 was recently shown to also inhibit NF-κB activation in response to stimulation of the intracellular NOD2 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2) receptor by muramyl dipeptide, which is the minimal peptidoglycan motif common to all bacteria (11). Interestingly, genome-wide association studies have recently identified the A20 locus as a candidate susceptibility locus in Crohn disease, for which NOD2 was previously identified as a susceptibility gene (12–14).

A20 not only is indispensable to restrict inflammation in response to bacterial infection but also seems to control the immune response to viral infection. Viral RNA is recognized by certain endosome-residing TLRs such as TLR3, as well as by RIG-I (cytosolic retinoic acid-inducible gene I), which induce type I interferon via the concerted action of NF-κB and IRFs. Hiscott and co-workers (15) showed that virus-induced expression of A20 efficiently blocks RIG-I-mediated activation of NF-κB and IRF3 but only weakly interferes with the response initiated by TLR3. On the other hand, two other studies using A20 overexpression or knockdown showed that A20 can also interfere with TLR3-induced IRF and NF-κB activation (16, 17). These results suggest that virus-inducible expression of A20 negatively regulates RIG-I- and TLR3-mediated induction of an antiviral state. However, recent studies with macrophages from A20-deficient mice have shown that A20 specifically regulates TLR3-induced NF-κB (but not IRF3) activation (8). In fact, DUBA has recently been identified as a specific regulator of the IRF3 signaling pathway (18).

Both overexpression and knockdown experiments have also shown an inhibitory effect of A20 on antigen receptor-induced NF-κB activation in lymphoid cells (19, 20), indicating that A20 is a critical regulator of the innate as well as adaptive immune system. Furthermore, loss of A20 expression has been found in ocular adnexal marginal zone B cell lymphoma, which led to the suggestion that A20 acts as a tumor suppressor gene whose disruption plays an important role in lymphomagenesis (19, 21). Further studies on the role of A20 in tumorigenesis are needed, however, to confirm this.

Although A20 has been studied mainly in the context of its NF-κB inhibitory function, it should be mentioned that A20 was originally characterized as an inhibitor of TNF-induced apoptosis (3), which was later confirmed in A20-deficient mice and cells. A20-negative thymocytes show enhanced TNF-induced apoptosis. In A20-deficient MEF cells, however, enhanced TNF sensitivity is only apparent when cells are pretreated with TNF, followed by administration of TNF and cycloheximide. These differences might be due to the constitutive versus inducible expression of A20 in T cells and MEFs, respectively (7, 22).

Molecular Mechanism of A20 Activity

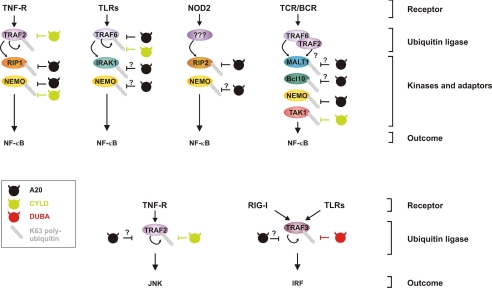

Since its original discovery in 1990, the mechanism of A20 activity has remained enigmatic for many years. It was only in 2004 that Dixit and co-workers (23) found that A20 interferes with TNF-induced NF-κB activation by acting as a dual ubiquitin-editing enzyme. During recent years, it has become clear that polyubiquitination is an integral part of NF-κB signaling (24). Whereas modification of IκBα with Lys48-linked ubiquitin chains is associated with its proteasomal degradation, modification of several signaling proteins with Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains regulates their interaction with other proteins. In TNF, IL-1, TLR, and RIG-I signaling to NF-κB, Lys63 ubiquitination is mediated by members of the TRAF (TNFR-associated factor) protein family, which function as E3 ubiquitin ligases (Fig. 1) (25–27). Lys63-ubiquitinated signaling proteins are then recognized by specific ubiquitin-binding scaffolding proteins that assemble and activate downstream kinases (e.g. Lys63-ubiquitinated RIP1 (receptor-interacting protein 1) is recognized by the IKKα/IKKβ adaptor NEMO) (28).

FIGURE 1.

Overview of different ubiquitinated targets of A20 in NF-κB, IRF, and JNK signaling pathways. Triggering of different receptors leads to the activation and autoubiquitination of specific members of the TRAF family, which also mediate the Lys63 ubiquitination of downstream kinases and other signaling proteins. Known and potential targets for A20-mediated deubiquitination are indicated. For comparison, ubiquitinated targets for CYLD and DUBA are also shown. Lys63 ubiquitin chains are depicted as beads on a string. TCR/BCR, T cell receptor/B cell receptor.

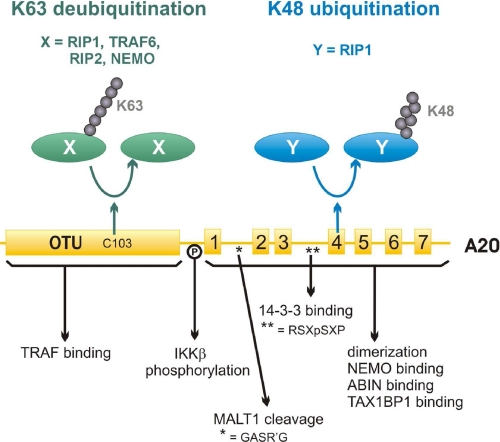

A first hint into the direction of a possible mechanism of action of A20 came from the observation that A20 contains an N-terminal domain that belongs to the OTU superfamily of deubiquitinating cysteine proteases (Fig. 2) (29), the structure of which has recently been elucidated (30, 31). A20 was subsequently shown to deubiquitinate Lys48 or Lys63 polyubiquitin chains in vitro (32). The real breakthrough came with the finding that A20 specifically removes Lys63 polyubiquitin chains from RIP1 (23), an essential signaling protein that is recruited together with A20 to TNFR (33). Mutation of the active-site Cys103 in the OTU domain abrogates the deubiquitinating and NF-κB inhibitory activity of A20 (23, 32). Others have reported that additional mutation of Asp100, which is part of the catalytic triad of the protease domain, is essential to fully abrogate the NF-κB inhibitory potential of A20 (34, 35). It should be noted, however, that these mutants (29),3 as well as A20 deletion mutants that lack the complete N-terminal OTU domain (36, 37), can still inhibit TNF-induced NF-κB activation upon overexpression in HEK293 cells, although with reduced efficiency compared with wild-type A20. These data indicate that the deubiquitinating activity of A20 might not always be required for NF-κB inhibition. Interestingly, the C-terminal domain of A20, composed of seven C2/C2 zinc fingers, has been shown to function as a ubiquitin ligase and to mediate Lys48 ubiquitination of RIP1, thereby targeting RIP1 for proteasomal degradation (Fig. 2) (23). Zinc finger 4 is crucial for the ubiquitin ligase activity of A20 (16), but also zinc finger 7 seems to be important for NF-κB inhibition (23, 38). Some of the zinc fingers in A20 might act as ubiquitin receptors, which is suggested by the observation that Rabex-5 is able to directly bind ubiquitin via an A20-like zinc finger motif (39). It is worth mentioning that A20 zinc finger 7 is also essential for the localization of A20 to a lysosome-associated endocytic membrane compartment (40). Although more experiments are needed to elucidate the mechanism of action of A20, its dual ubiquitin-editing activity on RIP1 introduces a novel concept in signaling research (reviewed in Ref. 41). Interestingly, Lys48 and Lys63 linkage-specific antibodies have recently been developed and already revealed a similar IL-1-induced sequential ubiquitin editing of IRAK-1 by a yet unknown enzyme (42). It is unlikely that RIP1 is the only target for A20 in the TNFR signaling pathway. A20 overexpression also results in NEMO deubiquitination (35), but the significance of this finding remains to be investigated. It is also still unclear if the anti-apoptotic and JNK inhibitory effects of A20 also depend on its ubiquitin-editing function. In this context, it is worth mentioning that Lys63 autoubiquitination of TRAF2 is indispensable for TNF-induced JNK activation (43), implicating TRAF2 as a potential target for A20 (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of the structural domains of human A20 involved in its ubiquitin-editing function and interaction with regulatory proteins. The N-terminal OTU domain mediates the deubiquitinating activity of A20 on RIP1, RIP2, TRAF6, and NEMO, whereas the C-terminal zinc finger domain mediates its ubiquitin ligase activity on RIP1. Regions involved in specific protein-protein interactions or post-translational modifications of A20 are also indicated.

Lys63 ubiquitination of specific proteins also plays a key role in NF-κB signaling in response to many other receptors than TNFR (44), and A20-mediated deubiquitination has been demonstrated in some of these pathways as well. For example, A20 abrogates TLR4-induced NF-κB activation by deubiquitinating TRAF6 (8, 9). Similarly, A20 can deubiquitinate RIP2, thus inhibiting NF-κB activation in response to NOD2 stimulation (Fig. 1) (11). It should be mentioned that other deubiquitinating enzymes such as Cezanne or CYLD can have similar targets (24). Remarkably, no other examples of A20-mediated Lys48 ubiquitination have been reported.

Regulation of A20 Activity

With the exception of thymocytes and peripheral T cells (7, 22), most cell types do not express A20 under resting conditions. A20 transcription is rapidly induced by a large number of stimuli that trigger the binding of NF-κB to two specific NF-κB-binding sites in the A20 promoter (6). At the protein level, several A20-binding proteins such as ABIN (A20-binding inhibitor of NF-κB) and TAX1BP1 have been proposed to regulate A20 activity. Similar to A20, overexpression of ABIN-1, -2, and -3 inhibits TNF-, IL-1-, and LPS-induced NF-κB activation, suggesting that these proteins may participate in the NF-κB inhibitory effect of A20 (24, 35, 45–48). Except for ABIN-3, ABIN proteins are ubiquitously expressed (49, 50). They all share a novel ubiquitin-binding domain, and mutations that disrupt the ubiquitin-binding potential of ABIN proteins also disrupt their NF-κB inhibitory effect (51, 52). A similar domain is present in NEMO, where it mediates the binding of NEMO to Lys63-ubiquitinated RIP1 and IRAK-1 (26, 53). In contrast, the ubiquitin-binding domain of ABIN-1 combined with a neighboring NEMO-binding domain mediates the interaction of ABIN-1 with ubiquitinated NEMO (52). Because ABIN-1 also augments A20-mediated deubiquitination of NEMO (35), these results suggest an important role for ABIN proteins in the targeting of A20 to specific ubiquitinated substrates. It should be mentioned that ABIN-2-deficient mice or cells do not show an enhanced NF-κB response (54), indicating possible redundancy between different ABIN proteins.

Binding of TAX1BP1 to A20 was originally described to be essential for the anti-apoptotic activity of A20 (55), although the mechanism remains unknown. More recently, TAX1BP1-deficient cells were shown to have a prolonged NF-κB response to IL-1, LPS, and TNF treatment, which is associated with elevated ubiquitination of RIP1 and TRAF6 (56, 57). More specifically, TAX1BP1 was shown to bind Lys63-ubiquitinated RIP1 and TRAF6, thus recruiting A20 to its substrate by forming a ternary complex (57). TAX1BP1 also recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch, which further augments Lys48 ubiquitination and degradation of RIP1. Consistent with these findings, Itch-deficient cells also show enhanced NF-κB activation in response to TNF (58). It is still unclear if Itch and A20 both ubiquitinate RIP1 or if Itch ubiquitinates a distinct target that somehow facilitates the ubiquitin ligase activity of A20.

A20 can also be regulated by post-translational modification (Fig. 2). TNF and LPS administration triggers the IKKβ-dependent phosphorylation of A20 at Ser381, which by a still unknown mechanism increases the ability of A20 to inhibit NF-κB activation (59). Phosphorylation of A20 at a 14-3-3-binding motif (RSKpSDP) between zinc fingers 3 and 4 has also been proposed, but the functional implication of this is still unclear (60). Recently, antigen receptor stimulation of T and B cells was shown to result in the site-specific cleavage of A20 by the paracaspase MALT1, resulting in the disruption of its NF-κB inhibitory potential (19). In addition, overexpression of the constitutively active API2-MALT1 fusion protein, which has been linked to mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, also results in A20 cleavage. These data emphasize an important role of MALT1-mediated A20 cleavage in the “fine-tuning” of antigen receptor signaling and possibly mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma development.

A20 in Human Disease

A20 intron single-nucleotide polymorphisms leading to decreased A20 expression are associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease in patients with type II diabetes (61). Also, mutation of a single amino acid (E627A) has been shown to correlate with increased sensitivity to atherosclerosis in mice (62). Consistent with these data, overexpression of A20 is protective in a mouse model for atherosclerosis, whereas mice haploinsufficient for A20 show increased lesion size (63). Interestingly, different genome-wide association studies have shown that multiple polymorphisms in the A20 region are independently associated with several autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (64, 65), systemic lupus erythomatosus (66, 67), and Crohn disease (12). Altogether, these findings underscore the importance of A20 in controlling inflammatory responses and indicate that A20 may be an important determinant for multiple autoimmune diseases. A better understanding of the mechanism of action and the regulation of A20 might thus form the basis for the development of novel anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported in part by grants from IAP6/18, the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, the Centrum voor Gezwelziekten, and the Geconcerteerde Onderzoeksacties of Ghent University. This is the second of three articles in the Thematic Minireview Series on Regulation of Signaling by Non-degradative Ubiquitination. This minireview will be reprinted in the 2009 Minireview Compendium, which will be available in January, 2010.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; IKK, IκB kinase; IL-1, interleukin-1; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNFR, TNF receptor; MEF, mouse embryo fibroblast; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IRF, interferon regulatory factor; NEMO, NF-κB essential modifier; OTU, ovarian tumor; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase.

I. Carpentier, K. Verhelst, and R. Beyaert, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Dixit, V. M., Green, S., Sarma, V., Holzman, L. B., Wolf, F. W., O'Rourke, K., Ward, P. A., Prochownik, E. V., and Marks, R. M. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265 2973–2978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyaert, R., Heyninck, K., and Van Huffel, S. (2000) Biochem. Pharmacol. 60 1143–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Opipari, A. W., Jr., Hu, H. M., Yabkowitz, R., and Dixit, V. M. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267 12424–12427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karin, M., and Greten, F. R. (2005) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner, S. L., Kearns, J. D., Zadorozhnaya, V., Lynch, C., O'Dea, E., Boldin, M. P., Ma, A., Baltimore, D., and Hoffmann, A. (2008) Genes Dev. 22 2093–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krikos, A., Laherty, C. D., and Dixit, V. M. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267 17971–17976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee, E. G., Boone, D. L., Chai, S., Libby, S. L., Chien, M., Lodolce, J. P., and Ma, A. (2000) Science 289 2350–2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turer, E. E., Tavares, R. M., Mortier, E., Hitotsumatsu, O., Advincula, R., Lee, B., Shifrin, N., Malynn, B. A., and Ma, A. (2008) J. Exp. Med. 205 451–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boone, D. L., Turer, E. E., Lee, E. G., Ahmad, R. C., Wheeler, M. T., Tsui, C., Hurley, P., Chien, M., Chai, S., Hitotsumatsu, O., McNally, E., Pickart, C., and Ma, A. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5 1052–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song, X. T., Kabler, K. E., Shen, L., Rollins, L., Huang, X. F., and Chen, S. Y. (2008) Nat. Med. 14 258–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hitotsumatsu, O., Ahmad, R. C., Tavares, R., Wang, M., Philpott, D., Turer, E. E., Lee, B. L., Shiffin, N., Advincula, R., Malynn, B. A., Werts, C., and Ma, A. (2008) Immunity 28 381–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(2007) Nature 447 661–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hugot, J. P., Chamaillard, M., Zouali, H., Lesage, S., Cezard, J. P., Belaiche, J., Almer, S., Tysk, C., O'Morain, C. A., Gassull, M., Binder, V., Finkel, Y., Cortot, A., Modigliani, R., Laurent-Puig, P., Gower-Rousseau, C., Macry, J., Colombel, J. F., Sahbatou, M., and Thomas, G. (2001) Nature 411 599–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogura, Y., Bonen, D. K., Inohara, N., Nicolae, D. L., Chen, F. F., Ramos, R., Britton, H., Moran, T., Karaliuskas, R., Duerr, R. H., Achkar, J. P., Brant, S. R., Bayless, T. M., Kirschner, B. S., Hanauer, S. B., Nunez, G., and Cho, J. H. (2001) Nature 411 603–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, R., Yang, L., Nakhaei, P., Sun, Q., Sharif-Askari, E., Julkunen, I., and Hiscott, J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 2095–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saitoh, T., Yamamoto, M., Miyagishi, M., Taira, K., Nakanishi, M., Fujita, T., Akira, S., Yamamoto, N., and Yamaoka, S. (2005) J. Immunol. 174 1507–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, Y. Y., Li, L., Han, K. J., Zhai, Z., and Shu, H. B. (2004) FEBS Lett. 576 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kayagaki, N., Phung, Q., Chan, S., Chaudhari, R., Quan, C., O'Rourke, K. M., Eby, M., Pietras, E., Cheng, G., Bazan, J. F., Zhang, Z., Arnott, D., and Dixit, V. M. (2007) Science 318 1628–1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coornaert, B., Baens, M., Heyninck, K., Bekaert, T., Haegman, M., Staal, J., Sun, L., Chen, Z. J., Marynen, P., and Beyaert, R. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stilo, R., Varricchio, E., Liguoro, D., Leonardi, A., and Vito, P. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121 1165–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honma, K., Tsuzuki, S., Nakagawa, M., Karnan, S., Aizawa, Y., Kim, W. S., Kim, Y. D., Ko, Y. H., and Seto, M. (2008) Genes Chromosomes Cancer 47 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tewari, M., Wolf, F. W., Seldin, M. F., O'Shea, K. S., Dixit, V. M., and Turka, L. A. (1995) J. Immunol. 154 1699–1706 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wertz, I. E., O'Rourke, K. M., Zhou, H., Eby, M., Aravind, L., Seshagiri, S., Wu, P., Wiesmann, C., Baker, R., Boone, D. L., Ma, A., Koonin, E. V., and Dixit, V. M. (2004) Nature 430 694–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wullaert, A., Heyninck, K., Janssens, S., and Beyaert, R. (2006) Trends Immunol. 27 533–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertrand, M. J., Milutinovic, S., Dickson, K. M., Ho, W. C., Boudreault, A., Durkin, J., Gillard, J. W., Jaquith, J. B., Morris, S. J., and Barker, P. A. (2008) Mol. Cell 30 689–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conze, D. B., Wu, C. J., Thomas, J. A., Landstrom, A., and Ashwell, J. D. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 3538–3547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, M. S., and Kim, Y. J. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76 447–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chau, T. L., Gioia, R., Gatot, J. S., Patrascu, F., Carpentier, I., Chapelle, J. P., O'Neill, L., Beyaert, R., Piette, J., and Chariot, A. (2008) Trends Biochem. Sci. 33 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balakirev, M. Y., Tcherniuk, S. O., Jaquinod, M., and Chroboczek, J. (2003) EMBO Rep. 4 517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komander, D., and Barford, D. (2008) Biochem. J. 409 77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, S. C., Chung, J. Y., Lamothe, B., Rajashankar, K., Lu, M., Lo, Y. C., Lam, A. Y., Darnay, B. G., and Wu, H. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 376 526–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans, P. C., Ovaa, H., Hamon, M., Kilshaw, P. J., Hamm, S., Bauer, S., Ploegh, H. L., and Smith, T. S. (2004) Biochem. J. 378 727–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang, S. Q., Kovalenko, A., Cantarella, G., and Wallach, D. (2000) Immunity 12 301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans, P. C., Smith, T. S., Lai, M. J., Williams, M. G., Burke, D. F., Heyninck, K., Kreike, M. M., Beyaert, R., Blundell, T. L., and Kilshaw, P. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 23180–23186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauro, C., Pacifico, F., Lavorgna, A., Mellone, S., Iannetti, A., Acquaviva, R., Formisano, S., Vito, P., and Leonardi, A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 18482–18488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klinkenberg, M., Van Huffel, S., Heyninck, K., and Beyaert, R. (2001) FEBS Lett. 498 93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song, H. Y., Rothe, M., and Goeddel, D. V. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93 6721–6725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Natoli, G., Costanzo, A., Guido, F., Moretti, F., Bernardo, A., Burgio, V. L., Agresti, C., and Levrero, M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 31262–31272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raiborg, C., Slagsvold, T., and Stenmark, H. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31 541–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, L., Hailey, D. W., Soetandyo, N., Li, W., Lippincott-Schwartz, J., Shu, H. B., and Ye, Y. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783 1140–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heyninck, K., and Beyaert, R. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newton, K., Matsumoto, M. L., Wertz, I. E., Kirkpatrick, D. S., Lill, J. R., Tan, J., Dugger, D., Gordon, N., Sidhu, S. S., Fellouse, F. A., Komuves, L., French, D. M., Ferrando, R. E., Lam, C., Compaan, D., Yu, C., Bosanac, I., Hymowitz, S. G., Kelley, R. F., and Dixit, V. M. (2008) Cell 134 668–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Habelhah, H., Takahashi, S., Cho, S. G., Kadoya, T., Watanabe, T., and Ronai, Z. (2004) EMBO J. 23 322–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adhikari, A., Xu, M., and Chen, Z. J. (2007) Oncogene 26 3214–3226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heyninck, K., De Valck, D., Vanden Berghe, W., Van Criekinge, W., Contreras, R., Fiers, W., Haegeman, G., and Beyaert, R. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 145 1471–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staege, H., Brauchlin, A., Schoedon, G., and Schaffner, A. (2001) Immunogenetics 53 105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Huffel, S., Delaei, F., Heyninck, K., De Valck, D., and Beyaert, R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 30216–30223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weaver, B. K., Bohn, E., Judd, B. A., Gil, M. P., and Schreiber, R. D. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27 4603–4616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wullaert, A., Verstrepen, L., Van Huffel, S., Adib-Conquy, M., Cornelis, S., Kreike, M., Haegman, M., El Bakkouri, K., Sanders, M., Verhelst, K., Carpentier, I., Cavaillon, J. M., Heyninck, K., and Beyaert, R. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verstrepen, L., Adib-Conquy, M., Kreike, M., Carpentier, I., Adrie, C., Cavaillon, J. M., and Beyaert, R. (2008) J. Cell. Mol. Med. 12 316–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heyninck, K., Kreike, M. M., and Beyaert, R. (2003) FEBS Lett. 536 135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner, S., Carpentier, I., Rogov, V., Kreike, M., Ikeda, F., Lohr, F., Wu, C. J., Ashwell, J. D., Dotsch, V., Dikic, I., and Beyaert, R. (2008) Oncogene 27 3739–3745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu, C. J., Conze, D. B., Li, T., Srinivasula, S. M., and Ashwell, J. D. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8 398–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papoutsopoulou, S., Symons, A., Tharmalingham, T., Belich, M. P., Kaiser, F., Kioussis, D., O'Garra, A., Tybulewicz, V., and Ley, S. C. (2006) Nat. Immunol. 7 606–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Valck, D., Jin, D. Y., Heyninck, K., Van de Craen, M., Contreras, R., Fiers, W., Jeang, K. T., and Beyaert, R. (1999) Oncogene 18 4182–4190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shembade, N., Harhaj, N. S., Liebl, D. J., and Harhaj, E. W. (2007) EMBO J 26 3910–3922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iha, H., Peloponese, J. M., Verstrepen, L., Zapart, G., Ikeda, F., Smith, C. D., Starost, M. F., Yedavalli, V., Heyninck, K., Dikic, I., Beyaert, R., and Jeang, K. T. (2008) EMBO J. 27 629–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shembade, N., Harhaj, N. S., Parvatiyar, K., Copeland, N. G., Jenkins, N. A., Matesic, L. E., and Harhaj, E. W. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9 254–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hutti, J. E., Turk, B. E., Asara, J. M., Ma, A., Cantley, L. C., and Abbott, D. W. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27 7451–7461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Valck, D., Heyninck, K., Van Criekinge, W., Vandenabeele, P., Fiers, W., and Beyaert, R. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 238 590–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boonyasrisawat, W., Eberle, D., Bacci, S., Zhang, Y. Y., Nolan, D., Gervino, E. V., Johnstone, M. T., Trischitta, V., Shoelson, S. E., and Doria, A. (2007) Diabetes 56 499–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Idel, S., Dansky, H. M., and Breslow, J. L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 14235–14240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolfrum, S., Teupser, D., Tan, M., Chen, K. Y., and Breslow, J. L. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 18601–18606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Plenge, R. M., Cotsapas, C., Davies, L., Price, A. L., de Bakker, P. I., Maller, J., Pe'er, I., Burtt, N. P., Blumenstiel, B., DeFelice, M., Parkin, M., Barry, R., Winslow, W., Healy, C., Graham, R. R., Neale, B. M., Izmailova, E., Roubenoff, R., Parker, A. N., Glass, R., Karlson, E. W., Maher, N., Hafler, D. A., Lee, D. M., Seldin, M. F., Remmers, E. F., Lee, A. T., Padyukov, L., Alfredsson, L., Coblyn, J., Weinblatt, M. E., Gabriel, S. B., Purcell, S., Klareskog, L., Gregersen, P. K., Shadick, N. A., Daly, M. J., and Altshuler, D. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39 1477–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomson, W., Barton, A., Ke, X., Eyre, S., Hinks, A., Bowes, J., Donn, R., Symmons, D., Hider, S., Bruce, I. N., Wilson, A. G., Marinou, I., Morgan, A., Emery, P., Carter, A., Steer, S., Hocking, L., Reid, D. M., Wordsworth, P., Harrison, P., Strachan, D., and Worthington, J. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39 1431–143317982455 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Musone, S. L., Taylor, K. E., Lu, T. T., Nititham, J., Ferreira, R. C., Ortmann, W., Shifrin, N., Petri, M. A., Ilyas Kamboh, M., Manzi, S., Seldin, M. F., Gregersen, P. K., Behrens, T. W., Ma, A., Kwok, P. Y., and Criswell, L. A. (2008) Nat. Genet. 40 1062–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Graham, R. R., Cotsapas, C., Davies, L., Hackett, R., Lessard, C. J., Leon, J. M., Burtt, N. P., Guiducci, C., Parkin, M., Gates, C., Plenge, R. M., Behrens, T. W., Wither, J. E., Rioux, J. D., Fortin, P. R., Graham, D. C., Wong, A. K., Vyse, T. J., Daly, M. J., Altshuler, D., Moser, K. L., and Gaffney, P. M. (2008) Nat. Genet. 40 1059–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.