Abstract

The cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP, also called catabolite gene activator protein or CAP) plays a key role in metabolic regulation in bacteria and has become a widely studied model allosteric transcription factor. On binding its effector cAMP in the N-terminal domain, CRP undergoes a structural transition to a conformation capable of specific DNA binding in the C-terminal domain and transcription initiation. The crystal structures of Escherichia coli CRP (EcCRP) in the cAMP-bound state, both with and without DNA, are known, although its structure in the off state (cAMP-free, apoCRP) remains unknown. We describe the crystal structure at 2.0Å resolution of the cAMP-free CRP homodimer from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (MtbCRP), whose sequence is 30% identical with EcCRP, as the first reported structure of an off-state CRP. The overall structure is similar to that seen for the cAMP-bound EcCRP, but the apo MtbCRP homodimer displays a unique level of asymmetry, with a root mean square deviation of 3.5Å between all Cα positions in the two subunits. Unlike structures of on-state EcCRP and other homologs in which the C-domains are asymmetrically positioned but possess the same internal conformation, the two C-domains of apo MtbCRP differ both in hinge structure and in internal arrangement, with numerous residues that have completely different local environments and hydrogen bond interactions, especially in the hinge and DNA-binding regions. Comparison of the structures of apo MtbCRP and DNA-bound EcCRP shows how DNA binding would be inhibited in the absence of cAMP and supports a mechanism involving functional asymmetry in apoCRP.

CRP2 belongs to the large CRP/FNR family of bacterial transcription factors that link a molecular sensor function to gene expression modulation (1–3). The best studied of these is CRP from Eschericia coli (EcCRP), although many homologous proteins have also been analyzed (4–6). The mechanism by which effector binding in the N-terminal domain controls DNA binding in the C-terminal domain over 30 Å away, with subsequent recruitment of RNA polymerase, has been a subject of extensive study (7–10). A general goal of these studies has been to infer allosteric mechanism by comparing the inactive and active states, ideally for the same protein. As yet, there is no single protein for which structures of both inactive and DNA-bound states are known.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (Mtb) is one of the world's most lethal microbes, currently infecting about one-third of human beings and killing about 5000 per day. The Mtb genome encodes 15 isoforms of adenylyl cyclase (11–14); thus cAMP is likely produced under a variety of metabolic conditions including interactions with host cells. Considering the known virulence role of adenylyl cyclase in other pathogens such as Bacillus anthracis (15, 16), cAMP signaling is likely involved in Mtb pathogenesis. The CRP ortholog in Mtb (MtbCRP, gene O69644_MYCTU (UniProt), Rv3676) has been biochemically characterized (17) and linked with 73 different promoters, including several that are involved with metabolic adaptation (18). Analysis of the regulatory functions of MtbCRP may provide information useful for designing antituberculosis strategies.

We report the crystal structure of MtbCRP, a homodimer of 224-residue subunits, in the absence of cAMP, refined at 2.0 Å resolution. The structure is distinctly asymmetric in its internal organization, probably as part of a mechanism for blocking transcription activity in the absence of cAMP.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Production and Purification of MtbCRP—MtbCRP was cloned from M. tuberculosis H37Rv chromosomal DNA (kindly provided by Drs. John Belisle and Patrick Brennan, Colorado State University), expressed in E. coli as a histidine-tagged protein, and purified by nickel affinity methods. The histidine tag was removed by thrombin, leaving the non-native 3-residue extension Gly-Ser-His at the N terminus of the protein. The selenomethionine form of the protein was produced similarly, using appropriate host strain and media. Methods are detailed in the supplemental materials.

Crystallization and Diffraction—Protein was prepared for crystallization by concentration to 20 mg/ml (0.65 mm dimer) in 150 mm NaCl, 25 mm sodium Tris, pH 8.0. Crystal screening and optimization were carried out by standard methods using vapor diffusion in hanging drops. Final crystal conditions were 10% (v/v) polyethylene glycol 8000, 100 mm sodium Hepes, pH 7.5, with a 2-h time course of isopropyl alcohol from 15 to 3% (details in the supplemental materials).

Structure Determination and Refinement—Diffraction data were collected from a crystal of the selenomethionyl protein to a resolution of 2.3 Å (supplemental Table S3) at National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) beamline X29 (Brookhaven National Labs, Upton, NY). The data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using the Denzo/Scalepack suite (19). Selenium locations were determined using SHELXD (20), and single-wavelength anomalous dispersion protein phases were calculated using PHENIX (21). The resulting map enabled subunit tracing and model construction using XFIT (22). Refinement was performed using the program Refmac5 (23); statistics are given in supplemental Table S4.

Diffraction data were also collected from a crystal of the native (non-selenium) protein to a resolution of 2.0 Å (supplemental Table S3) at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) beamline 24-ID (Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL). The data were indexed, integrated, and scaled as above. The 2.3 Å selenium-phased model from the previous paragraph was used as a starting model for the native structure and further refined at 2.0 Å resolution by additional rounds of model adjustment using XFIT and restrained refinement using Refmac5. This led to the final model with Rfree = 0.284 described below (statistics are in the supplemental tables), analyzed using PROCHECK (24), and deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 3D0S.

RESULTS

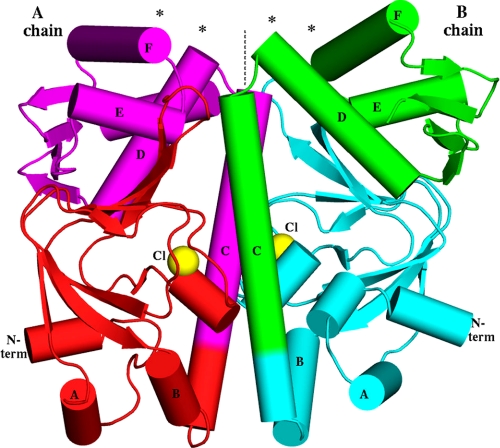

In the refined cAMP-free MtbCRP structure, the A chain contains the complete native sequence (residues 1–224; supplemental Fig. S1), whereas the B chain includes the 3-residue N-terminal extension but lacks residues 216–224 due to disorder. The quality of the experimental map (see supplemental Fig. S2), the final map (see Fig. 2), and the model are good (estimated coordinate error, 0.22 Å; full statistics in supplemental Tables S2–S4), except for one weak region, residues 1–25 of the A chain, which have no crystal contacts and have thermal factors about twice the overall mean of 37.0 Å2. Overall the structure generally resembles that of EcCRP, with the same secondary structure elements except for the fact that MtbCRP, which has 8 additional residues at the N terminus, forms three additional short helices in the N-domain (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1). Unfortunately, this gives the important, highly conserved helices in the C-domain different numbers, so to facilitate comparison, the lettering designations used for helices in EcCRP are maintained in this study. Thus the long central helix is called helix C, the hinge helix is D, and the two helices in the helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding motif are E and F. The N-terminal cAMP-binding domain is linked to the C-terminal DNA-binding domain by the long C helix (residues 116–144 in the A subunit), which also forms the majority of the dimer interface. Although no cAMP was added, the cAMP sites appear partially occupied, principally by a large monoatomic anion bound by the guanidinyl group of Arg-89 and between the amide-presenting main chain turns at residues 80–82 and residues 90–91. This anion site corresponds closely with the phosphoryl site in cAMP-complexed EcCRP structures. This adventitious ligand has been modeled as chloride (crystal conditions include NaCl at ∼100 mm); in addition, several water molecules are bound in the cAMP-binding regions.

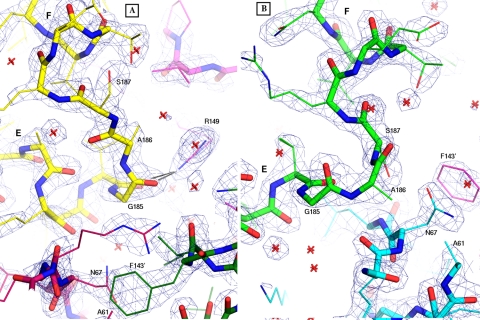

FIGURE 2.

Electron density for the HTH regions, showing the final refined 2Fo – Fc map contoured at 1.8 σ. Helices E and F are labeled in both panels. A, for the A chain, the HTH is colored yellow, the hairpin is dark red, and the hinge region is magenta. The hinge region of the B chain is colored dark green. Black lines show the two H-bonds from Arg-149 to the carbonyls of Val-184 and Gly-185. B, for the B chain, the HTH is colored green, and the hairpin is cyan. The prime symbol is used in each panel to indicate Phe-143 from the other subunit. Note the different conformations of residues 185–187 (labeled) in the HTH turn, the different locations of Asn-67 and Phe-143′, and the involvement of Arg-149 in subunit A only. Water molecules are represented as red stars. Images made using PyMOL (27).

FIGURE 1.

Overall shape of the MtbCRP homodimer. The molecular dyad is vertical (dashed line). Asterisks show the DNA-binding regions at the N termini (N term) of the D and F helices. The locations of the observed chloride ions, coinciding with the phosphate moiety of the cAMP-binding pocket, are shown as yellow spheres. Note that the B chain has an extra short helix in its N-domain, whereas the A chain has an extra helix (the C-terminal helix G, behind D and E in this view) in the C-domain. Because the view direction is perpendicular to the dyad, the image would have approximate mirror symmetry if the dimer were two-fold symmetric, but in fact there are many deviations from mirror symmetry, e.g. the purple E helix is much closer to the dyad than the green E helix is.

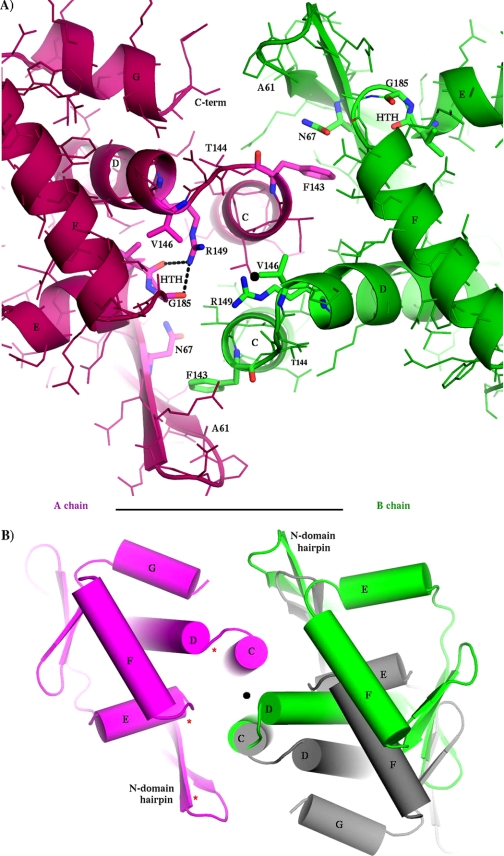

The dimer is asymmetric in both domains, but the N-domains differ only by isolated rotamers and smooth global deformations, generally preserving the local environment of each residue. The differences in the C-domains are more profound, involving many residues that have completely different local environments, including different H-bonds. The r.m.s.d. between the two C-domains (70 Cα positions) is 3.1 Å. The most asymmetric features are in the HTH DNA-binding region (helices E and F) and the hinge region (junction of helices C and D). Hinge residue Arg-149 (which is conserved as Arg-142 in EcCRP; see supplemental Fig. S1 for sequence alignment) in the first turn of helix D has a different conformation in the two subunits (see Fig. 3A; also see supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). In the A subunit, Arg-149 projects outward from the dyad and forms two H-bonds with the carbonyl oxygens of Val-184 and Gly-185 in the HTH motif. In the B subunit, Arg-149 extends inward, grazing the dyad, and caps helix C. This position of Arg-149 (in the B subunit) would be impossible for both Arg-149 residues to hold simultaneously because of overlap at the molecular dyad. These differences, together with different main chain conformations at residues 143–144 and different rotamers of Leu-141, combine to give Arg-149 a completely different relation to Leu-141 in the two subunits (supplemental Fig. S3), and this difference appears coupled to a repositioning of helix D, which in subunit B approaches closer to the molecular dyad than in subunit A (see Figs. 3 and 4 and supplemental Fig. S2). This position near the dyad is occupied by helix E in subunit A. With helix D occupying this location in subunit B, helix E is forced farther counterclockwise, and the entire C-domain is rotated by about 30° relative to its position in subunit A (see Fig. 3). In addition to these differences, the C-terminal helix G (which is absent in the shorter EcCRP) is disordered in subunit B. As in EcCRP, the N-domain extends the tip of its β-roll hairpin (strands 4 and 5) to interact with the C-domain, but these contacts are different in the two subunits, with different sets of H-bonds, consistent with different positions of helices D and E with respect to the N-domain. Near the tip of each hairpin, it contacts the hinge of the opposite subunit, burying the phenyl group of Phe-143 (conserved as Phe-136 in EcCRP) in both cases, but although Phe-143 of the A subunit is covered by Asn-67 of the B subunit, Phe-143 of the B subunit is covered by Ala-61 of the A subunit (Figs. 2 and 3A; also supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 3.

Asymmetry of C-domains, as viewed down the molecular pseudodyad from the DNA-binding region. In both panels, the MtbCRP crystal structure is shown (subunit A in purple, subunit B in green) with a black dot indicating the position of the molecular dyad (center). A, close up of hinge regions showing all side chains with selected side chains emphasized and labeled. Note that the two hinges have fundamentally different geometries, giving different environments to many dyad-related residues; the three side chains Asn-67, Val-146, and Arg-149 are labeled in both subunits as examples. The two Asn-67 side chains are on opposite sides of the adjacent Phe-143 ring, the two Val-146 side chains are at very different distances from the dyad, and the two Arg-149 guanidino groups are both to the left of the dyad. Also note that the two HTH elements are in different positions with respect to the dyad. The Cα–Cα distance between Arg-149 and Gly-185 of the HTH is 8.7 Å in the A subunit and is 18.9 Å in the B subunit. B, overall view of C-domains, adding (in gray) the hypothetical position of the B subunit if the dimer were symmetric. The C-terminal helix G is observed (ordered) only in the A subunit. The rotational discrepancy (green to gray) in this projection is about 25 degrees. Note that in addition to the different positions of the green and gray domains, they are different in their internal organization (especially the relations of helices E-to-F and E-to-D) and in their relation to the N-domain hairpin, which they both contact. Three red asterisks indicate (for the A subunit) three locations at which DNA phosphates interact with cAMP-bound EcCRP in PDB structure 1ZRF.

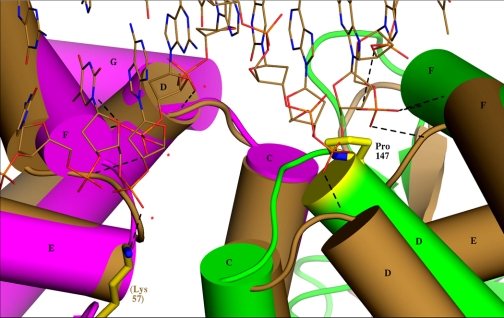

FIGURE 4.

Superposition of cAMP-free MtbCRP (subunit A in purple, subunit B in green) onto the DNA complex of active EcCRP (PDB: 1ZRF) (both subunits brown, DNA runs across top of figure) in the hinge region. The least-squares superposition utilized the 65 Cα atoms of helices C, D, E, and F in subunit A, for which the r.m.s. deviation is 1.32 Å. Three consecutive phosphates (indicated by red asterisks for subunit A on the left) of the DNA form H-bonds (under 3.3 Å in at least one subunit, represented by dashed lines) with each subunit in the EcCRP complex. The contacts are to the N terminus of helix D, the HTH turn between helices E and F (three H-bonds), and to Lys-57 of the N-domain hairpin (which for clarity is shown only in subunit A). The MtbCRP A chain (purple) superposes closely onto cAMP-bound EcCRP, but the B chain deviates significantly (green and brown), making it unlikely that the H-bonds could form. In addition, the green helix D is higher than the brown so that the side chain of Pro-147 (yellow) projects into the space occupied by a phosphate in the EcCRP complex.

In contrast with the distinct dimorphisms in the C-domains, there is no residue in the N-domain whose environment differs completely between the two subunits. The two N-domains are similar (omitting residues 1–20, the r.m.s.d. over 97 Cα positions is 1.5 Å) but are positioned asymmetrically around the dyad. The largest differences are in the cAMP-binding sites and the N-terminal 25 residues, which in the A-chain lack crystal contacts and have a less compact conformation than in the B chain. The cAMP-binding regions are well ordered and contain chloride anions at similar positions, corresponding to the phosphoryl moieties in cAMP-bound EcCRP structures, and several water molecules whose positions differ between the two subunits. Nearby residues Asp-45, Arg-59, Ser-82, and Ser-91 have different rotamers, and four residues on helix C have different rotamers: Leu-131, Thr-134, Asn-137, and Leu-141. In addition, throughout the length of the central helix C (residues 116–144), the B subunit is slightly “below” the A subunit so that a translation of about 1 Å along the dyad would be required, in addition to dyad symmetry, to superpose them. This is probably correlated with the aforementioned rotamer differences and with numerous dimorphic H-bonds involving helix C. In particular, an H-bond from Asn-135 in subunit B to dimorphic Thr-134 in subunit A appears positioned to stabilize the translational asymmetry of the two helices.

DISCUSSION

The observed intersubunit differences in conformations and residue environments in MtbCRP extend throughout the homodimer and thus appear to go beyond the influence of crystal packing effects. We are unaware of any case in which crystal packing perturbs the symmetry of a dimer so profoundly; therefore we believe that the observed asymmetry is intrinsic to the structure of cAMP-free CRP and probably has a functional role.

EcCRP and MtbCRP share 30% sequence identity, and each isolated domain aligns closely between the two proteins (r.m.s.d. values are under 2.0 Å in comparisons with the structure of the ternary cAMP·DNA·EcCRP complex PDB ID: 1ZRF) with the exception of the C-domain in subunit B of MtbCRP (r.m.s.d. = 3.7 Å for this domain between MtbCRP and the EcCRP complex). The consensus promoter DNA sequences to which both CRPs bind are similar, being dominated by the sequence GTGA at 4–7 bases upstream of the dyad (17). Therefore the structure of cAMP-activated MtbCRP is likely to be similar to that of EcCRP in the cAMP·DNA ternary complex. In that complex, three consecutive DNA phosphates from each strand form H-bonds to the protein near the molecular dyad. Phosphate x10 (z10) forms a close interaction (under 2.9 Å in both subunits) with the amide of Val-139, capping helix D. Phosphate x9 (z9) forms three H-bonds with the turn of the HTH motif, and phosphates x/z8 form H-bonds with Lys-57 (which is Arg-65 in MtbCRP). Forming these interactions requires that the protein has the six H-bonding regions symmetrically disposed and in the correct spatial arrangement. In the MtbCRP structure, the arrangement of these six groups is asymmetric, and the arrangement of the B chain alone is incompatible with DNA binding (Fig. 4). The deviation of the B chain from symmetry is more than a rigid body motion; it is distorted (apparently by impingements with hinge A and its own N-domain), and the distortion particularly affects the HTH turn where the DNA would bind (Fig. 2; supplemental Fig. S4). In addition to these deterrents, the previously described structure of the B chain hinge causes the side chain of Pro-147 to be in an elevated position that occupies the Van der Waals space where phosphate z10 would bind, thus appearing to provide a direct block to effective DNA binding (Fig. 4). Farther from the dyad, several additional phosphate-protein interactions that account for DNA bending in the EcCRP·cAMP·DNA complex, appear to be abrogated for MtbCRP by the conformation of its B chain.

On the basis of the present structure, it appears that MtbCRP may inhibit specific DNA binding and transcription by assuming an intrinsically asymmetric structure not only in the somewhat flexible hinge rotations, as is observed in EcCRP and other homologs, but in the protein core itself. In this scenario, the present structure represents a conformation of cAMP-free CRP that is so deeply asymmetric that it is incapable of symmetrizing its DNA-binding regions by hinge flexion. The effect of cAMP binding would then be to symmetrize the protein core, thus enabling the C-domains to become symmetric (although due to their flexibility, they may still be observed in asymmetric positions in the absence of DNA).

In recent years, the structures of several CRP homologs have been reported (4–6), but still, there is no single protein for which both the off-state and the fully on-state (DNA complex) structures are known. An additional complication is the possibility that some homologs may have a reverse mode of activation, binding DNA only in the absence of effector (25). On-state structures without DNA must be interpreted with care because the large diversity of known C-domain orientations (including “active” ones that are asymmetric) suggests that the hinge is flexible and may, in the absence of DNA, be subject to adventitious perturbation. Thus the role of activation by cAMP would be to render the C-domains capable of assuming a symmetric DNA-binding conformation but not of forcing this conformation. In fact, some flexibility is probably important for forming the DNA complex.

In the present structure, the difference in the internal arrangements of the C-domain of MtbCRP in the two subunits cannot be due simply to flexible swinging at the hinges. The close resemblance of the A chain to that of cAMP-bound EcCRP, along with the steric impossibility for both chains simultaneously to assume the conformation of subunit B, suggests that the protein switches the conformation of only one (or primarily of one) of the two subunits. This provides a plausible explanation for the single site binding and negative cooperativity that have been reported for EcCRP (26) because the two cAMP-binding sites in apoCRP would be expected to have different cAMP affinities, and only one of them (probably the one in subunit B) may need to bind cAMP to promote the transition of the dimer to its more symmetric on-state.

We suggest that the observed MtbCRP structure represents the functional off-state of CRP and that transcription of CRP-dependent genes is inhibited as a result of its acute asymmetry. We note that the precise mechanism by which cAMP binding promotes the transition to a symmetric, transcription-inducing conformation remains unknown. Additional structural information, particularly the structures of a single protein in the apo, cAMP-bound, and fully active (DNA-bound) forms, will be important for completely defining the allosteric mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the gift of M. tuberculosis H37Rv chromosomal DNA from Drs. John Belisle and Patrick Brennan, Colorado State University, the technical and logistical support of Darwin Diaz and Dawn Rode, the support of the U.S. Department of Energy (Biological and Environmental Research) and the National Institutes of Health (National Center for Research Resources) for data collected at NSLS beamline X29, and the support of the Northeast Collaborative Access Team (NECAT) at Argonne National Laboratories Advanced Photon Source.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3D0S) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental text, four supplemental tables, and three supplemental figures.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: CRP, cAMP receptor protein; EcCrp, Escherichia coli CRP; Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv; MtbCrp, M. tuberculosis H37Rv CRP dimer; HTH, helix-turn-helix; r.m.s., root-mean-square; r.m.s.d., root-mean-square deviation; SAD, single-wavelength anomalous dispersion; PDB, Protein Data Bank.

References

- 1.Kolb, A. S., Busby, H., Buc, S., Garges, S., and Adhya, S. (1993) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 62 749–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harman, J. G. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1547 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Napoli, A. A., Lawson, C. L., Ebright, R. H., and Berman, H. M. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 357 173–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyce, M. G., Levy, C., Gabor, K., Pop, S. M., Biehl, B. D., Doukov, T. I., Ryter, J. M., Mazon, H., Smidt, H., van den Heuvel, R. H., Ragsdale, S. W., van der Oost, J., and Leys, D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 28318–28325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borjigin, M., Li, H., Lanz, N. D., Kerby, R. L., Roberts, G. P., and Poulos, T. L. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 63 282–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eiting, M., Hageluken, G., Schubert, W. D., and Heinz, D. W. (2005) Mol. Microbiol. 56 433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, J., Adhya, S., and Garges, S. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89 9700–9704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Passner, J. M., Schultz, S. C., and Steitz, T. A. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 304 847–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Youn, H., Kerby, R. L., Conrad, M., and Roberts, G. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 1119–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawson, C. L., Swigon, D., Murakami, K. S., Darst, S. A., Berman, H. M., and Ebright, R. H. (2004) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCue, L. A., McDonough, K. A., and Lawrence, C. E. (2000) Genome Res. 10 204–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy, S. K., Kamireddi, M., Dhanireddy, K., Young, L., Davis, A., and Reddy, P. T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 35141–35149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo, Y. L., Seebacher, T., Kurz, U., Linder, J. U., and Schultz, J. E. (2001) EMBO J. 20 3667–3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shenoy, A. R., Sreenath, N. P., Mahalingam, M., and Visweswariah, S. S. (2005) Biochem. J. 387 541–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leppla, S. H. (1982) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79 3162–3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masure, H. R., Shattuck, R. L., and Storm, D. R. (1987) Microbiol. Rev. 51 60–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai, G., McCue, L. A., and McDonough, K. A. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187 7795–7804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akhter, Y., Tundup, S., and Hasnain, S. E. (2007) J. Med. Microbiol. 297 451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otwinowski, Z., and Minor, W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider, T. R., and Sheldrick, G. M. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58 1772–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams, P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Hung, L. W., Ioerger, T. R., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Read, R. J., Sacchettini, J. C., Sauter, N. K., and Terwilliger, T. C. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McRee, D. (1999) J. Struct. Biol. 125 156–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A., and Dodson, E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laskowski, R. A., Macarthur, M. W., Moss, D. S., and Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agari, Y., Kashihara, A., Yokoyama, S., Kuramitsu, S., and Shinkai, A. (2008) Mol. Microbiol. 70 60–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leu, S. F., Baker, C. H., Lee, E. J., and Harman, J. G. (1999) Biochemisty 38 6222–6230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeLano, W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Visualization System, 0.99 Ed., DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.