Abstract

The mitochondria are the major intracellular source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are generated during cellular respiration. The role of peroxiredoxin (Prx) III, a 2-Cys Prx family member, in the scavenging of mitochondrial H2O2 has recently been emphasized. While eliminating H2O2, Prx can become overoxidized and inactivated by modifying the active cysteine into cysteine sulfinic acid (Cys-SO2H). When 2-Cys Prxs are inactivated in vitro, sulfiredoxin (Srx) reduces the cysteine sulfinic acid to cysteines. However, whereas Srx is localized in the cytoplasm, Prx III is present exclusively in the mitochondria. Although Srx reduces sulfinic Prx III in vitro, it remains unclear whether the reduction of Prx III in cells is actually mediated by Srx. Our gain- and loss-of-function experiments show that Srx is responsible for reducing not only sulfinic cytosolic Prxs (I and II) but also sulfinic mitochondrial Prx III. We further demonstrate that Srx translocates from the cytosol to mitochondria in response to oxidative stress. Overexpression of mitochondrion-targeted Srx promotes the regeneration of sulfinic Prx III and results in cellular resistance to apoptosis, with enhanced elimination of mitochondrial H2O2 and decreased rates of mitochondrial membrane potential collapse. These results indicate that Srx plays a crucial role in the reactivation of sulfinic mitochondrial Prx III and that its mitochondrial translocation is critical in maintaining the balance between mitochondrial H2O2 production and elimination.

Peroxiredoxins (Prxs)2 are a family of enzymes that catalyze the reduction of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and hydroperoxides to water and alcohol, respectively (1–5). The six isoforms of mammalian Prx (Prx I to Prx VI) are classified into three subfamilies: 2-Cys, atypical 2-Cys, and 1-Cys (2, 6). Prx I to Prx IV, which belong to the 2-Cys Prx subfamily, exist as homodimers and contain two conserved cysteine residues. In the catalytic cycle of 2-Cys Prxs, the conserved N-terminal Cys-SH is first oxidized by peroxides to cysteine sulfenic acid (Cys-SOH), which then reacts with the conserved COOH-terminal Cys-SH of the other subunit in the homodimer to form a disulfide bond. This disulfide is specifically reduced by thioredoxin, whose oxidized form is then regenerated by thioredoxin reductase, using NADPH-reducing equivalents (2–5, 7). As a result of the slow conversion rate to a disulfide, the sulfenic intermediate is occasionally further oxidized to cysteine sulfinic acid (Cys-SO2H), which causes inactivation of peroxidase that cannot be reduced by thioredoxin (7–9). Studies on the fate of the sulfinylated Prx enzyme have shown that its sulfinylation is actually a reversible reaction in mammalian cells (10). The enzyme responsible for the reduction of sulfinylated Prx was subsequently identified in yeast and named sulfiredoxin (Srx) (11). Sulfiredoxin regenerates inactive 2-Cys Prxs, returning it to the catalytic cycle and preventing its permanent oxidative inactivation by strong oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the antioxidant capacity of the cell (12). Accumulating evidence suggests that oxidative stress is involved in aging (13) and the pathology of many conditions, including cancer and cardiovascular, inflammatory, and degenerative diseases (14). The mitochondria are the major intracellular source of ROS, which are generated during cellular respiration. Mitochondrial ROS production is thought to be associated with the activation and propagation of apoptotic and necrotic cell death (15). Therefore, a tightly regulated balance exists between mitochondrial ROS production and mitochondrial antioxidant defense systems. Key among these is the mitochondrial Prx III system, which is an important reducer of mitochondrial H2O2. Recent studies have shown that Prx III protects cells against mitochondrially derived oxidative stress by removing mitochondrial H2O2 (16–21).

Unique among the 2-Cys Prx members, Prx III is localized specifically within the mitochondria (22). Mammalian mitochondria also contain thioredoxin 2 (23) and thioredoxin reductase 2 (24), which function as electron suppliers for the catalytic cycle of Prx III. These three proteins make up a primary line of defense against H2O2 in mitochondria. Like cytosolic Prx I and Prx II, mitochondrial Prx III is hyperoxidized and inactivated in cells under oxidative stress (25–33). Hyperoxidized Prx III is promptly regenerated to protect cells from mitochondrial H2O2-mediated oxidative damage (25–27). However, whereas Prx III is localized to mitochondria, Srx is found in the cytosol (34). Although Srx is capable of catalyzing the reduction of sulfinic Prx III in vitro (35), it remains unclear whether the in vivo reduction of Prx III is mediated by Srx. In the present study, we examined the functional ability of Srx to reduce sulfinic Prx III under oxidative stress in vivo. We found that Srx translocates from the cytosol into mitochondria to regenerate hyperoxidized Prx III. We further demonstrate that cells overexpressing mitochondria-targeted Srx are resistant to mitochondrial ROS-mediated cell death through the restoration of the peroxidase activity of Prx III.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—Dulbecco's minimum essential cell culture medium, and F-12 Nutrient Mixture (Ham's F-12) medium were obtained from WelGENE Inc. (Daegu, Republic of Korea). pcDNA3 vector, Alexa-488-conjugated goat antibodies to mouse IgG, Alexa-594-conjugated goat antibodies to rabbit IgG, MitoTracker Red CMXRos, tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE), and 5,6-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA) were purchased from Invitrogen. pFLAG-CMV2 vector, FLAG M2 monoclonal, and anti-FLAG polyclonal antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin were from HyClone Laboratories Inc. (Logan, UT). Polyclonal antibodies to Prx-SO2, Prx I, and Prx III and monoclonal antibodies to Prx III were purchased from Ab Frontier (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Monoclonal antibodies to α-tubulin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and G418 was obtained from Invitrogen.

Construction of Expression Vectors—cDNA encoding human Srx (34) was subcloned into the mammalian expression vectors pcDNA3, pFLAG-CMV2, and pcDNA3 containing a C-terminal FLAG tag, to generate pcDNA3-Srx, pFLAG-CMV2-Srx, and pcDNA3-Srx-FLAG, respectively. To target Srx expression to mitochondria, a cDNA corresponding to the first 62 amino acids of human Prx III leader sequence (2, 36, 37) was cloned into the N terminus coding region of Srx in pcDNA3-Srx-FLAG, thus generating pcDNA3-mitoSrx-FLAG. A vector that expresses a catalytic cysteine mutant of Srx, pcDNA3-mitoSrx(C99S)-FLAG, was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the Quick-Change kit (Stratagene).

Cell Culture and Establishment of Stable Cells—HeLa (human cervical carcinoma), HEK 293 (human embryonic kidney cells), and A549 (human lung carcinoma) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, with the exception of the A549 cells, which were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium. HeLa and HEK293 cells were transfected using the FuGENE6 reagent (Roche Applied Science). RNA interference was used to deplete Srx in A549 cells, using the Amaxa Nucleofection system (AMAXA Biosystems) as described previously (34). Cells were transfected with a small interference RNA targeted against a portion of the human Srx mRNA open reading frame (5′-GGAGGUGACUACUUCUACU-3′) as well as a control RNA duplex of random sequence were obtained from Dharmacon Research. To generate stably transfected cell lines, HEK293 cells were transfected with pcDNA3-mitoSrx-FLAG, pcDNA3-mitoSrx(C99S)-FLAG, or pcDNA3 mock vector as a control using the FuGENE6 reagent. Clones were selected in the presence of G418 (0.4 mg/ml) and maintained in medium containing G418 (0.2 mg/ml).

Immunoblot Analysis—Cell lysates were fractionated by SDS-PAGE or two-dimensional gel electrophoresis as described previously (8, 10). The separated proteins were transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was then incubated with the primary antibodies. Immune complexes were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Biosciences).

Subcellular Fractionation—Cells in hypotonic buffer (25 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5) were left on ice for 30 min and then homogenized using a Polytron-Aggregate homogenizer (Kinematica Inc., Luzern, Switzerland) in the presence of protease inhibitors (1 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonylfluoride hydrochloride, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, and 5 μg/ml leupeptin). Isotonicity was re-established by adding an equal volume of hypertonic buffer (500 mm sucrose, 25 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.5). Cell homogenates were separated into postnuclear supernatant (PNS) and pellets containing unbroken cells and nuclei by centrifugation at 750 × g for 10 min. The PNS was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min to collect the mitochondria-enriched heavy membrane (HM) pellets. This supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min; the final supernatant was collected as the cytosolic fraction. The HM pellets were washed three times in H buffer (200 mm mannitol, 70 mm sucrose, 1 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, and 0.1% fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin) and then lysed in 20 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 2 mm EGTA, 1 mm EDTA, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mm 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonylfluoride hydrochloride.

Confocal Microscopy—Cells were grown on glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTeK), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized for 5 min with 0.2% Triton X-100. FLAG-tagged Srx was detected with FLAG M2 monoclonal antibodies (10 μg/ml) and Alexa-488-conjugated goat antibodies raised against mouse IgG (5 μg/ml). Endogenous Prx III was detected with polyclonal antibodies (10 μg/ml) and Alexa-594-conjugated goat antibodies raised against rabbit IgG (5 μg/ml). Mitochondria were stained with 0.1 μm MitoTracker Red CMXRos. Confocal fluorescence images were obtained using an LSM510 microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Flow Cytometry—A FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) was used for all analyses, with a minimum of 2 × 104 cells per sample for each measurement. The excitation wavelength was 488 nm, and the observation wavelength was 530 nm for green fluorescence and 585 nm for red fluorescence. The relative change in fluorescence was analyzed with WinMDI software. To analyze apoptosis, cells were stained with propidium iodide (25 μg/ml), and the percentage of hypodiploid (apoptotic) cells was determined. To evaluate mitochondrial membrane potential changes (ΔΨm), cells (2 × 105) were incubated with 100 nm of TMRE for 20 min at 37 °C, and the shifts in red fluorescence emissions of TMRE were measured. To measure intracellular ROS, detached cells were loaded with 5 μm CM-H2DCFDA at 37 °C for 20 min, washed, and then analyzed immediately by flow cytometry.

RESULTS

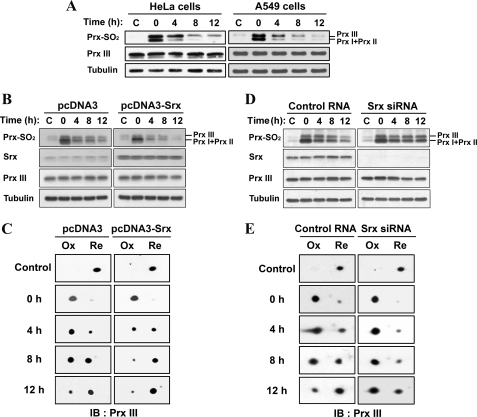

Srx Reduces Sulfinic Forms of Mitochondrial Prx III in Cells—HeLa and A549 cells were exposed to 200 μm H2O2 for 10 min and then incubated for various times in H2O2-free medium, after which cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1A). We previously developed a method to monitor the reduction of sulfinic 2-Cys Prx enzymes by immunoblot analysis with antibodies (anti-2-Cys Prx-SO2) that specifically recognize both sulfinic and sulfonic forms of these proteins (25). Given that the sizes of Prx I and Prx II are identical, their overoxidized forms cannot be differentiated by immunoblot analysis. Based on their molecular weight and our previous data (25), the lower band is overoxidized Prx I/II, and the upper band corresponds to overoxidized Prx III. The intensity of the oxidized Prx I and II band gradually decreased with time after H2O2 removal. Interestingly, a gradual reduction of sulfinic Prx III was also apparent in these cells. Whereas Srx is localized in the cytoplasm (34), Prx III is present exclusively in the mitochondria. Srx has been shown to reduce sulfinic Prx III in vitro (35), but it remains unclear whether the reduction of Prx III in cells is actually mediated by Srx.

FIGURE 1.

Srx reduces sulfinic forms of mitochondrial Prx III in cells. HeLa and A549 cells were cultured under normal conditions (A). A549 cells were transfected with either pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-Srx (B and C) or with human Srx-specific siRNA or control RNA (D and E) and then cultured for 24 h. All cells were exposed to 200 μm H2O2 for 10 min, washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution, and cultured for the indicated times in culture media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (A, B, and D) or two-dimensional PAGE (C and E) followed by immunoblot analysis with antibodies specific to sulfinic 2-Cys Prxs (Prx-SO2), Srx, Prx III, and α-tubulin. The region on the two-dimensional immunoblots corresponds to a molecular mass of ∼28 kDa and an isoelectric point of 5.9–6.4 characteristic of Prx III. The positions of oxidized (Ox) and reduced (Re) Prx III are indicated.

To assess the role of Srx in the reduction of sulfinic Prx III, we transfected A549 human lung epithelial cells with either an expression vector containing human Srx (Fig. 1, B and C) or a small interfering RNA (siRNA) specific for human Srx (Fig. 1, D and E), respectively. The transfected cells were exposed to 200 μm H2O2 for 10 min to induce protein sulfinylation and then incubated for various times in the absence of H2O2. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-2-Cys Prx-SO2 (Fig. 1, B and D). The rate of reduction was greatly increased in the cells overexpressing Srx (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the rate was markedly decreased in Srx siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 1D).

We also subjected the cell lysates to two-dimensional electrophoresis. Antibodies to Prx III revealed a nearly complete acidic shift of Prx III, following exposure of the cells to H2O2. This shift was followed by the gradual reversion of the immunoreactive spots to the normal position after H2O2 removal. Consistent with the results obtained by one-dimensional immunoblot analysis, the reduction of sulfinic forms of Prx III was promoted by Srx overexpression (Fig. 1C) but retarded by Srx depletion (Fig. 1E). Because Prx III is a mitochondrial protein, our finding that Srx is substantially responsible for reducing sulfinic forms of mitochondrial Prx III in cells suggests that Srx may traffic into the mitochondria under oxidative stress.

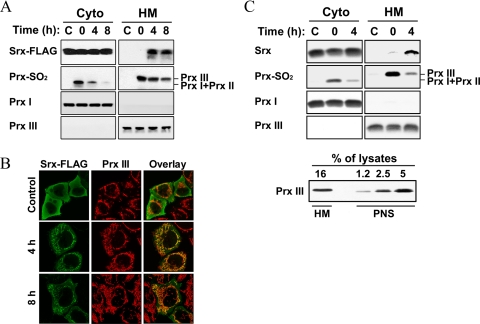

Cytosolic Srx Is Translocated into the Mitochondria under Oxidative Conditions—The discrepancy in the subcellular localization between Srx and Prx III raises the possibility that Srx could translocate to the mitochondria in response to H2O2. To examine this possibility, we investigated the intracellular localization of Srx under basal conditions and after oxidative stress, using subcellular fractionation (Fig. 2A) and confocal immunofluorescence (Fig. 2B). HeLa cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged Srx were treated with H2O2, and cell homogenates were separated into subcellular fractions. The localization of FLAG-Srx was examined by immunoblot analysis of both the soluble cytosolic and the HM fractions. The fractions were probed using antibodies against cytosolic Prx I and mitochondrial Prx III. In agreement with our previous data (34), Srx was not found in the mitochondria-containing HM fraction. A significant increase of FLAG-tagged Srx was found in the HM fraction of cells only at 4 and 8 h after H2O2 treatment, accompanied by a decrease of sulfinic Prx III. This result was confirmed by immunostaining (Fig. 2B). HeLa cells expressing FLAG-tagged Srx displayed a diffuse cytosolic pattern of Srx under basal conditions. FLAG-tagged Srx resided in both mitochondria and the cytosol at both 4 and 8 h after H2O2 treatment. We have previously shown that N terminus-tagged Srx is catalytically active as untagged Srx (35). In separate experiments, we observed that endogenous, untagged Srx also redistributed to mitochondria under oxidative conditions (Fig. 2C). To exclude a probable contamination of cytosolic Srx in HM fractions, HM pellets were repeatedly washed. By comparing the resulting band intensities, we observed that 16% of Prx III proteins in the HM fraction were prepared from ∼3.9% of them in the initial PNS fraction, indicating that only 24% of Prx III in the PNS was recovered in the final HM fraction after heavy washing (Fig. 2C, lower panel). 6 and 60% aliquots of cytosolic and HM fractions, prepared from the identical PNS, were analyzed by immunoblotting, and then the band intensities of Srx were measured as 28,213 and 2,705, respectively, at 4 h after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 2C, upper panel). Taking into account the HM preparation yield, ∼3.8% of the total Srx was present in the HM fraction at 4 h after H2O2 treatment. These results show that Srx can translocate from the cytosol to mitochondria to reduce the sulfinic form of Prx III.

FIGURE 2.

Mitochondrial translocation of Srx under oxidative conditions. HeLa cells transfected with an expression vector for FLAG-tagged Srx (A and B) and normally grown A549 cells (C) were exposed to 200 μm H2O2 for 10 min and then allowed to recover from oxidative stress as in Fig. 1. A and upper panel of C, after the indicated times, cell homogenates were separated into nuclear pellet and postnuclear supernatant (PNS). 0.5 ml of PNS was further separated into 0.5 ml of cytosolic (Cyto) and mitochondria-enriched heavy membrane (HM) fractions, and then the latter was prepared as 0.05 ml of lysates. Equal volumes (0.03 ml) of Cyto fractions and HM lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. Lower panel of C, the indicated percent volumes of aliquots from HM lysates (0.05 ml) or PNS (0.5 ml) were subjected to immunoblot analysis for Prx III. B, cells were stained for the FLAG epitope (green) and Prx III (red) and then examined by confocal microscopy.

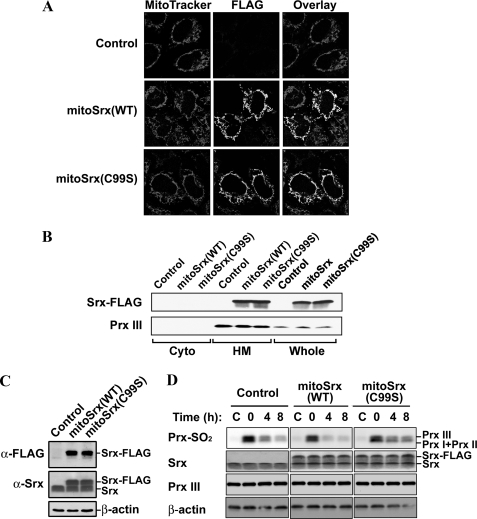

Effects of Mitochondria-targeted Srx Overexpression on the Reduction of Sulfinic Prx III—To investigate the catalytic action of mitochondria-targeted Srx overexpression on Prx III regeneration, we constructed expression plasmids for mitochondria-targeted FLAG-tagged wild-type Srx (mitoSrx(WT)) and mutant Srx (mitoSrx(C99S)), in which the catalytic Cys99 was replaced by Ser. To express Srx that would target to the mitochondria, cDNA corresponding to the first 62 amino acids of human Prx III leader sequence (2, 36, 37) was cloned into the N terminus coding region of Srx. Confocal immunolocalization (Fig. 3A) and subcellular fractionation analysis (Fig. 3B) revealed that the overexpressed mitoSrx(WT) and mitoSrx(C99S) proteins were successfully targeted to mitochondria. To examine the capacity of mitoSrx to enhance reduction of sulfinic Prx III in mitochondria, we created HEK293 cell lines that were stably transfected with either mitoSrx(WT) or mitoSrx(C99S). The level of mitoSrx(WT) and mitoSrx(C99S) expression in all such cell lines was ∼1.5-fold that of endogenous Srx (Fig. 3C). Cell lines stably expressing mitoSrx(WT) or mitoSrx(C99S) are hereafter designated as mitoSrx(WT) and mitoSrx(C99S) cells, respectively. Control cells were stably transfected with empty vector alone. Cells were exposed to 100 μm H2O2 for 10 min to induce protein sulfinylation and then incubated for 4 and 8 h in the absence of H2O2. Cells expressing mitoSrx(WT) in mitochondria showed a significantly increased rate of Prx III regeneration compared with control or mitoSrx(C99S) cells, demonstrating that overexpression of mitochondrion-targeted Srx efficiently accelerates the regeneration of sulfinic Prx III.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of mitochondria-targeted Srx overexpression on the reduction of sulfinic Prx III. HeLa cells were transfected for 24 h with pcDNA3 (Control), pcDNA3-mitoSrx-FLAG (which encodes mitoSrx-FLAG), or pcDNA3-mitoSrx(C99S)-FLAG (which encodes mitoSrx(C99S)-FLAG), respectively (A and B). A, cells were stained with MitoTracker (red) and an antibody to the FLAG epitope (green) and then examined by confocal microscopy. B, immunoblots for cytosolic (Cyto) and mitochondria-enriched heavy membrane (HM) fractions were performed with polyclonal antibodies specific to the FLAG epitope and Prx III. Immunoblots of whole-cell lysates (Whole) are also shown. C, immunoblot analysis of lysates prepared from HEK293 cells stably transfected with plasmids as described above using antibodies specific to the FLAG epitope, Srx, and β-actin. D, the stably transfected cells were exposed to 200 μm H2O2 for 10 min and then allowed to recover from oxidative stress as in Fig. 1. After the indicated times, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblot analysis with specific antibodies to sulfinic 2-Cys Prxs (Prx-SO2), Srx, Prx III, and β-actin.

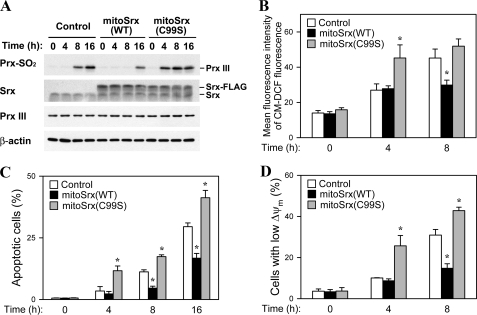

Effects of Mitochondria-targeted Srx Overexpression on Rotenone-induced Apoptotic Phenotypes—We looked at the effects of ectopic mitoSrx expression on steady-state level of sulfinic Prx III in cells treated with rotenone, which inhibits NADH conversion to NAD through respiratory Complex I (Fig. 4A). The increased level of sulfinic Prx III in rotenone-treated cells is indicative of an increase in the steady-state proportion of inactivated Prx III, resulting from an accumulation of mitochondrial H2O2. The extent of Prx III sulfinylation was apparently increased at 8 h after rotenone treatment in control cells. At 8 h, the level of inactivated sulfinic Prx III was markedly lower in mitoSrx(WT) cells than in control cells, indicating that mitoSrx(WT) can enhance the rate of reactivation of sulfinic Prx III and help to maintain the steady-state level of active Prx III under mitochondrial ROS-mediated oxidative stress. Cells expressing mitoSrx(C99S) showed a more rapid increase in Prx III sulfinylation when exposed to rotenone than cells expressing either vector alone or mitoSrx(WT).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of mitochondria-targeted Srx overexpression on rotenone-induced apoptotic phenotypes. A, stable overexpression of mitoSrx(WT) and mitoSrx(C99S) in HEK293 cells was examined by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific to sulfinic 2-Cys Prxs (Prx-SO2), Srx, Prx III, and β-actin. Stable cell lines were cultured in the presence of 50 μm rotenone for indicated times (A–D). B, cells were loaded with CM-H2DCFDA, and fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry to quantify intracellular ROS. C, cells were analyzed for DNA content using flow cytometry following staining with propidium iodide. Apoptotic cells were defined as those with a DNA content less than that typically present in cells during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. D, TMRE-loaded cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for detection of ΔΨm. Data in B–D are means ± S.D. of triplicates. The asterisk indicates significant difference from the control group (p < 0.01).

To determine whether mitoSrx expression inhibits the accumulation of cellular H2O2 following rotenone treatment, which promotes generation of mitochondrial ROS, we compared the abundance of ROS in control, mitoSrx(WT), and mitoSrx(C99S) cells using the oxidant-sensitive fluorescent indicator CM-H2DCFDA. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that the intracellular ROS level was significantly increased by rotenone treatment in control cells. After treatment with rotenone for 8 h, less ROS accumulated in mitoSrx(WT) cells than in control cells (Fig. 4B). This increase in ROS abundance is mainly attributable to enhanced generation and accumulation of mitochondrial ROS via inhibition of mitochondrial complex I (38). Our data suggest that mitoSrx overexpression results in a decrease in the steady-state level of mitochondrial H2O2, which then diffuses into the cytosol.

Mitochondria are recognized sources of H2O2 and the superoxide radical (39) and are key players in the initiation of apoptosis in many systems. We therefore examined the effect of mitoSrx expression on rotenone-induced apoptosis in control, mitoSrx(WT), and mitoSrx(C99S) cells. We quantified apoptotic cells by flow cytometry after staining with propidium iodide. The number of cells with subdiploid (<2N) DNA content, representing cells undergoing apoptosis, at 8 and 16 h after exposure to rotenone was decreased ∼2-fold by mitoSrx(WT) expression, but increased ∼1.5-fold by mitoSrx(C99S) expression (Fig. 4C).

Mitochondrial ROS-induced apoptosis is associated with a reduction in membrane potential (ΔΨm). We therefore examined the effects of mitoSrx expression on this event. The change in ΔΨm was measured using the cationic dye TMRE, which accumulates in the mitochondria in proportion to the mitochondrial membrane potential. Flow cytometric analysis of red fluorescence indicated that treating cells with rotenone induced a decrease in ΔΨm. Rotenone-induced dissipation of ΔΨm was attenuated by mitoSrx(WT) expression but exacerbated by mitoSrx(C99S) expression (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that mitoSrx(WT) suppresses mitochondrial ROS-mediated apoptosis by restoring the peroxidase activity of Prx III in mitochondria.

DISCUSSION

Various aging and pathological conditions are related to an increase in mitochondrial generation of ROS (13, 15, 40). Mitochondrial H2O2 is thus tightly regulated by mitochondrial antioxidant defense systems. The role of Prx III in scavenging mitochondrial H2O2 has been emphasized. Previous studies have shown that Prx III is vulnerable to inactivation through hyperoxidation of its active site cysteine residues in cells and rodent tissues under oxidative stress (25–33). Sulfinic Prx III can be specifically reduced back to the thiol form in mammalian cells (25–27). Consistent with previous studies, our data show that Prx III sulfinylation is a reversible reaction in mammalian cells. Our results further show that the reduction and reactivation of sulfinic Prx III are promoted by overexpression of Srx and inhibited by knockdown of Srx. A recent study using bone marrow-derived macrophages from Srx-deficient mice has also demonstrated that Srx plays a crucial role in the reduction of the sulfinic form of Prx III as well as Prx I and II (27). Previous results from cortical neurons showed that inducing Srx expression by synaptic activity or nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor activator inhibits the formation of sulfinic Prx III following oxidative stress, which contributes to its neuroprotective effects (32, 33). Thus, our results are consistent with these previous studies and indicate that Srx is substantially responsible for the reduction of sulfinic forms of Prx III.

Our present study uses subcellular fractionation and immunomicroscopy to show that Srx translocates from the cytosol to the mitochondria in response to oxidative stress. Srx does not contain a mitochondrial targeting sequence, raising the question of what mechanism underlies the ability of the Srx protein to enter the mitochondria to reduce sulfinic Prx III. Our observation is similar to previous findings that cytosolic DJ-1 or p66Shc protein translocate to mitochondria following oxidative stress (41, 42). Further research is required to elucidate translocation mechanism of Srx.

Recent findings demonstrate that mitochondrial H2O2 can induce intracellular oxidative stress and is implicated in aging (43–46) and the pathogenesis of diabetes (47, 48) and cardiovascular disease, among others (17, 49–51). Several studies have shown that overexpressing Prx III can protect cells against oxidative injuries (52, 53) and that depleting Prx III in HeLa cells can lead to increased intracellular levels of H2O2 and sensitize cells to induction of apoptosis by staurosporine or TNF-α (16). This suggests that Prx III plays a cytoprotective role by quenching H2O2 in mitochondria. Recent studies have demonstrated that Prx III overexpression can protect mice from mitochondrial dysfunction and left ventricular failure after myocardial infarction (17). Transgenic mice overexpressing Prx III have shown a specifically increased scavenging activity in mitochondria, increased resistance to apoptosis, and improved glucose tolerance (48). Deleting Prx III in mice resulted in an increased level of intracellular ROS, which correlated with increased oxidation of DNA/protein in alveolar epithelium and severe lung inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (19). These gain- and loss-of-function studies suggest that Prx III is an important protein for protecting an organism from the pathogenesis of mitochondrial H2O2-associated diseases. A previous study of ours also showed that H2O2 generated by the mitochondria functions in conjunction with multiple factors to amplify the apoptotic signal (16). It seems that the peroxidase activity of Prx III is modulated both by the level of mitochondrial H2O2 and by the activity of Srx. When there is not enough reduced Prx III to handle mitochondrial H2O2, accumulation of sulfinic Prx III takes place, which could lead to an even greater increase in mitochondrial H2O2. We therefore wondered whether Srx could also protect against mitochondrial H2O2-mediated cell death through restoration of the peroxidase activity of Prx III. Our results now provide support for this scenario. Overexpression of mitochondrion-targeted Srx (mitoSrx) efficiently promoted the regeneration of sulfinic Prx III and contributed to the elimination of mitochondrial H2O2 induced by rotenone. The decreased accumulation of sulfinic Prx III that resulted from mitoSrx overexpression thus decreased the rate of apoptosis in rotenone-treated cells. Our data now indicate that mitoSrx facilitates the reduction of hyperoxidized Prx III and promotes cellular resistance to mitochondrial H2O2-mediated apoptosis. Additionally, mitoSrx overexpression results in a decrease in the level of mitochondrial H2O2 (Fig. 4B), which then diffuses into the cytosol and takes part in hyperoxidation of Prx I and II. Therefore, the regeneration of cytosolic Prx I and II also promoted by expression of mitoSrx (Fig. 3D).

Overexpression of inactive Srx(C99S) in mitochondria leads to a more rapid oxidation of Prx III after rotenone treatment (Fig. 4A), whereas it does not appear to be the case after H2O2 treatment (Fig. 3D). The level of sulfinic Prx III in rotenone-treated cells is a steady-state level controlled both by rotenone-induced H2O2 and by the Srx activity. It seems that the mitoSrx(C99S) in rotenone-treated cells could act in a dominant negative manner by interfering with the interactions between endogenous Srx and sulfinic Prx III during several hours. In contrast, Prx III is almost completely hyperoxidized only within 10 min after treatment of H2O2 (Fig. 1, C and E). Because sulfinic reduction by Srx is a very slow process (kcat = 0.18/min) (34), Srx may hardly reduce sulfinic Prx III for a short period in the presence of an excess amount of H2O2, indicating that a dominant negative effect of mitoSrx(C99S) could not be shown in this condition (Fig. 3D).

Cell viability and function are critically dependent on the maintenance of a balance between mitochondrial ROS production and elimination. The loss of this balance can result in cell death, as well as the death of the organism. The importance of tight regulation of the mitochondrial H2O2 in aging and of the pathogenesis of age-associated disease has recently been emphasized (54). For example, transgenic mice that overexpress catalase in mitochondria show significantly increased H2O2 scavenging activity in mitochondria and extended lifespans (46). Thus, both aging and the development of age-related diseases could be influenced by insufficient elimination of mitochondrial H2O2 due to an overaccumulation of sulfinic Prx III or the inability of Srx to reduce oxidatively damaged Prx III over time. These data suggest therapeutic implications for modulating the activity of Srx in cell survival. For instance, treatments that promote mitochondrial translocation of Srx may reduce the effects of aging and age-related degenerative diseases.

In conclusion, we have shown that Srx traffics into mitochondria in response to oxidative stress and plays a crucial role in regenerating Prx III by reducing overoxidized Prx III. Overexpression of mitochondrion-targeted Srx efficiently promotes the restoration of Prx III and results in cellular resistance to apoptosis with enhanced elimination of mitochondrial H2O2 and decreased rates of ΔΨm collapse. Our data thus indicate that mitochondrial translocation of Srx is critical in maintaining balance between mitochondrial H2O2 production and elimination.

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation funded by the Korean government (the Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development, Grant KRF-2006-331-C00195 to T. S. C.), an Ewha Womans University Research Grant for 2005 (to T. S. C.), the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) Bio R&D Program funded by the Korean government (MEST, Grant M10642040002-07N4204-00210 to T. S. C.), Grant R15-2006-020 from the National Core Research Center program of the MEST, KOSEF through the Center for Cell Signaling & Drug Discovery Research at Ewha Womans University, the Seoul R&BD Program (Grant 10527 to T. S. C.), and the second stage of the Brain Korea 21 Project (to Y. H. N. and J. Y. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Prx, peroxiredoxin; Srx, sulfiredoxin; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TMRE, tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester; CM-H2DCFDA, 5-(and 6-)chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; ΔΨm, mitochondrial membrane potential; siRNA, small interfering RNA; PNS, postnuclear supernatant; HM, heavy membrane; mitoSrx, mitochondrion-targeted sulfiredoxin; MnSOD, Mn2+-dependent superoxide dismutase; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

References

- 1.Chae, H., Robison, K., Poole, L., Church, G., Storz, G., and Rhee, S. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 7017–7021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhee, S. G., Kang, S. W., Chang, T. S., Jeong, W., and Kim, K. (2001) IUBMB Life 52 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofmann, B., Hecht, H. J., and Flohe, L. (2002) Biol. Chem. 383 347–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood, Z. A., Schroder, E., Robin Harris, J., and Poole, L. B. (2003) Trends Biochem. Sci. 28 32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee, S. G., Chae, H. Z., and Kim, K. (2005) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38 1543–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seo, M. S., Kang, S. W., Kim, K., Baines, I. C., Lee, T. H., and Rhee, S. G. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 20346–20354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chae, H. Z., Chung, S. J., and Rhee, S. G. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 27670–27678 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, K. S., Kang, S. W., Woo, H. A., Hwang, S. C., Chae, H. Z., Kim, K., and Rhee, S. G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 38029–38036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabilloud, T., Heller, M., Gasnier, F., Luche, S., Rey, C., Aebersold, R., Benahmed, M., Louisot, P., and Lunardi, J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 19396–19401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woo, H. A., Chae, H. Z., Hwang, S. C., Yang, K.-S., Kang, S. W., Kim, K., and Rhee, S. G. (2003) Science 300 653–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biteau, B., Labarre, J., and Toledano, M. B. (2003) Nature 425 980–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thannickal, V. J., and Fanburg, B. L. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 279 L1005–L1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkel, T., and Holbrook, N. J. (2000) Nature 408 239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halliwell, B., and Gutteridge, J. M. C. (2007) Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 4th Ed., pp. 488–613, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- 15.Orrenius, S., Gogvadze, V., and Zhivotovsky, B. (2007) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47 143–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang, T. S., Cho, C. S., Park, S., Yu, S., Kang, S. W., and Rhee, S. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 41975–41984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsushima, S., Ide, T., Yamato, M., Matsusaka, H., Hattori, F., Ikeuchi, M., Kubota, T., Sunagawa, K., Hasegawa, Y., Kurihara, T., Oikawa, S., Kinugawa, S., and Tsutsui, H. (2006) Circulation 113 1779–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukhopadhyay, S. S., Leung, K. S., Hicks, M. J., Hastings, P. J., Youssoufian, H., and Plon, S. E. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 175 225–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, L., Shoji, W., Takano, H., Nishimura, N., Aoki, Y., Takahashi, R., Goto, S., Kaifu, T., Takai, T., and Obinata, M. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 355 715–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, L., Shoji, W., Oshima, H., Obinata, M., Fukumoto, M., and Kanno, N. (2008) FEBS Lett. 582 2431–2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Simoni, S., Goemaere, J., and Knoops, B. (2008) Neurosci. Lett 433 219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watabe, S., Hiroi, T., Yamamoto, Y., Fujioka, Y., Hasegawa, H., Yago, N., and Takahashi, S. Y. (1997) Eur. J. Biochem. 249 52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spyrou, G., Enmark, E., Miranda-Vizuete, A., and Gustafsson, J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 2936–2941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, S. R., Kim, J. R., Kwon, K. S., Yoon, H. W., Levine, R. L., Ginsburg, A., and Rhee, S. G. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 4722–4734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woo, H. A., Kang, S. W., Kim, H. K., Yang, K. S., Chae, H. Z., and Rhee, S. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 47361–47364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chevallet, M., Wagner, E., Luche, S., van Dorsselaer, A., Leize-Wagner, E., and Rabilloud, T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 37146–37153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diet, A., Abbas, K., Bouton, C., Guillon, B., Tomasello, F., Fourquet, S., Toledano, M. B., and Drapier, J. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 36199–36205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito, Y., Nishio, K., Ogawa, Y., Kinumi, T., Yoshida, Y., Masuo, Y., and Niki, E. (2007) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 42 675–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cumming, R. C., Dargusch, R., Fischer, W. H., and Schubert, D. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 30523–30534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cordray, P., Doyle, K., Edes, K., Moos, P. J., and Fitzpatrick, F. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 32623–32629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, Y. M., Park, S. H., Shin, D.-I., Hwang, J.-Y., Park, B., Park, Y.-J., Lee, T. H., Chae, H. Z., Jin, B. K., Oh, T. H., and Oh, Y. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 9986–9998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papadia, S., Soriano, F. X., Leveille, F., Martel, M. A., Dakin, K. A., Hansen, H. H., Kaindl, A., Sifringer, M., Fowler, J., Stefovska, V., McKenzie, G., Craigon, M., Corriveau, R., Ghazal, P., Horsburgh, K., Yankner, B. A., Wyllie, D. J., Ikonomidou, C., and Hardingham, G. E. (2008) Nat. Neurosci. 11 476–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soriano, F. X., Leveille, F., Papadia, S., Higgins, L. G., Varley, J., Baxter, P., Hayes, J. D., and Hardingham, G. E. (2008) J. Neurochem. 107 533–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang, T. S., Jeong, W., Woo, H. A., Lee, S. M., Park, S., and Rhee, S. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 50994–51001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woo, H. A., Jeong, W., Chang, T. S., Park, K. J., Park, S. J., Yang, J. S., and Rhee, S. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 3125–3128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Araki, M., Nanri, H., Ejima, K., Murasato, Y., Fujiwara, T., Nakashima, Y., and Ikeda, M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 2271–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chae, H. Z., Kim, H. J., Kang, S. W., and Rhee, S. G. (1999) Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 45 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, N., Ragheb, K., Lawler, G., Sturgis, J., Rajwa, B., Melendez, J. A., and Robinson, J. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 8516–8525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chance, B., Sies, H., and Boveris, A. (1979) Physiol. Rev. 59 527–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wallace, D. C. (1999) Science 283 1482–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, H. M., Niki, T., Taira, T., Iguchi-Ariga, S. M., and Ariga, H. (2005) Free Radic. Res. 39 1091–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orsini, F., Migliaccio, E., Moroni, M., Contursi, C., Raker, V. A., Piccini, D., Martin-Padura, I., Pelliccia, G., Trinei, M., Bono, M., Puri, C., Tacchetti, C., Ferrini, M., Mannucci, R., Nicoletti, I., Lanfrancone, L., Giorgio, M., and Pelicci, P. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 25689–25695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinton, P., Rimessi, A., Marchi, S., Orsini, F., Migliaccio, E., Giorgio, M., Contursi, C., Minucci, S., Mantovani, F., Wieckowski, M. R., Del Sal, G., Pelicci, P. G., and Rizzuto, R. (2007) Science 315 659–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giorgio, M., Migliaccio, E., Orsini, F., Paolucci, D., Moroni, M., Contursi, C., Pelliccia, G., Luzi, L., Minucci, S., Marcaccio, M., Pinton, P., Rizzuto, R., Bernardi, P., Paolucci, F., and Pelicci, P. G. (2005) Cell 122 221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Migliaccio, E., Giorgio, M., Mele, S., Pelicci, G., Reboldi, P., Pandolfi, P. P., Lanfrancone, L., and Pelicci, P. G. (1999) Nature 402 309–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schriner, S. E., Linford, N. J., Martin, G. M., Treuting, P., Ogburn, C. E., Emond, M., Coskun, P. E., Ladiges, W., Wolf, N., Van Remmen, H., Wallace, D. C., and Rabinovitch, P. S. (2005) Science 308 1909–1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Menini, S., Amadio, L., Oddi, G., Ricci, C., Pesce, C., Pugliese, F., Giorgio, M., Migliaccio, E., Pelicci, P., Iacobini, C., and Pugliese, G. (2006) Diabetes 55 1642–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen, L., Na, R., Gu, M., Salmon, A. B., Liu, Y., Liang, H., Qi, W., Van Remmen, H., Richardson, A., and Ran, Q. (2008) Aging Cell 7 866–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Francia, P., delli Gatti, C., Bachschmid, M., Martin-Padura, I., Savoia, C., Migliaccio, E., Pelicci, P. G., Schiavoni, M., Luscher, T. F., Volpe, M., and Cosentino, F. (2004) Circulation 110 2889–2895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Napoli, C., Martin-Padura, I., de Nigris, F., Giorgio, M., Mansueto, G., Somma, P., Condorelli, M., Sica, G., De Rosa, G., and Pelicci, P. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 2112–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rota, M., LeCapitaine, N., Hosoda, T., Boni, A., De Angelis, A., Padin-Iruegas, M. E., Esposito, G., Vitale, S., Urbanek, K., Casarsa, C., Giorgio, M., Luscher, T. F., Pelicci, P. G., Anversa, P., Leri, A., and Kajstura, J. (2006) Circ. Res. 99 42–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hattori, F., Murayama, N., Noshita, T., and Oikawa, S. (2003) J. Neurochem. 86 860–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nonn, L., Berggren, M., and Powis, G. (2003) Mol. Cancer Res. 1 682–689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giorgio, M., Trinei, M., Migliaccio, E., and Pelicci, P. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8 722–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]