Abstract

Macrophages act to protect the body against inflammation and infection by engaging in chemotaxis and phagocytosis. In chemotaxis, macrophages use an actin-based membrane structure, the podosome, to migrate to inflamed tissues. In phagocytosis, macrophages form another type of actin-based membrane structure, the phagocytic cup, to ingest foreign materials such as bacteria. The formation of these membrane structures is severely affected in macrophages from patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS), an X chromosome-linked immunodeficiency disorder. WAS patients lack WAS protein (WASP), suggesting that WASP is required for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. Here we have demonstrated that formin-binding protein 17 (FBP17) recruits WASP, WASP-interacting protein (WIP), and dynamin-2 to the plasma membrane and that this recruitment is necessary for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. The N-terminal EFC (extended FER-CIP4 homology)/F-BAR (FER-CIP4 homology and Bin-amphiphysin-Rvs) domain of FBP17 was previously shown to have membrane binding and deformation activities. Our results suggest that FBP17 facilitates membrane deformation and actin polymerization to occur simultaneously at the same membrane sites, which mediates a common molecular step in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. These results provide a potential mechanism underlying the recurrent infections in WAS patients.

Podosomes (see Fig. 1A) are micron-scale, dynamic, actin-based protrusions observed in motile cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells, osteoclasts, certain transformed fibroblasts, and carcinoma cells (1). Podosomes play an important role in macrophage chemotactic migration, which is critical for recruitment of leukocytes to inflamed tissues. Podosomes are both adhesion structures and the sites of extracellular matrix degradation (2). Adhesion to and degradation of the extracellular matrix are essential processes for the successful migration of macrophages in tissues. Podosomes occur in most macrophages and can be observed by differentiating human primary monocytes into macrophages with macrophage-colony stimulating factor-1 (M-CSF-1)2 and staining the F-actin using phalloidin (3, 4). Podosomes labeled in this way appear as F-actin-rich dots (see Fig. 1C). Podosome formation has recently been directly observed in vitro and in vivo in leukocyte migration through the endothelium, diapedesis (5).

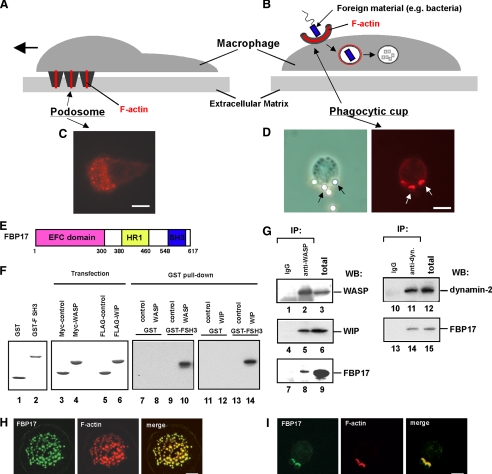

FIGURE 1.

FBP17 is a component of podosomes and phagocytic cups. A and B, schematic drawings of podosomes (A) and a phagocytic cup (B) in macrophages. C, podosomes in macrophages were visualized by F-actin staining using Alexa Fluor 568-phalloidin. D, macrophages incubated with IgG-opsonized latex beads formed phagocytic cups to ingest the beads. A phase contrast image of a macrophage forming phagocytic cups (left panel). Black arrows indicate the latex beads ingested by the macrophage. Phagocytic cups were visualized by F-actin staining using Alexa Fluor 568-phalloidin (right panel). White arrows indicate the phagocytic cups. The bar is 10 μm. E, the domain organization of FBP17. HR1, protein kinase C-related kinase homology region 1. F, FBP17 interacts directly with WASP and WIP via its SH3 domain. GST and the GST-FBP17 SH3 domain fusion protein (GST-FSH3) were purified from bacteria extracts. Purified proteins were subjected toSDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (lanes 1 and 2). HEK293 cells were transfected with the cDNAs of Myc-tagged control protein (Myc-PDZ-GEF), Myc-WASP, FLAG-PDZ-GEF, or FLAG-WIP, and the expression of those proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting (lanes 3–6). Lysates from the HEK293 transfected cells were incubated with the affinity matrices of GST alone or GST-FSH3. Pull-down samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Myc antibody (lanes 7–10) and anti-FLAG antibody (lanes 11–14). G, FBP17 binds WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2. WASP was immunoprecipitated (IP) from the lysates of PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells with anti-WASP or a control IgG (left panel, lanes 1–9). The WASP immunoprecipitates and total lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting (WB) for WASP (lanes 1–3), WIP (lanes 4–6), and FBP17 (lanes 7–9). Dynamin was also immunoprecipitated from the THP-1 cell lysates with an anti-dynamin polyclonal antibody. The dynamin immunoprecipitates and total lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting for dynamin-2 (lanes 10–12) and FBP17 (lanes 13–15). H and I, confocal laser scanning micrographs of PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells. H, THP-1 cells transfected with FLAG-tagged FBP17 cDNA (FBP17) were double-stained with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (left panel) and phalloidin (center panel) to visualize the F-actin in podosomes. Yellow indicates co-localization of FBP17 (green) and F-actin, podosomes (red) (right panel). I, THP-1 cells transfected with FLAG-FBP17 cDNA were incubated with IgG-opsonized latex beads and double-stained with anti-FLAG antibody and phalloidin. Phagocytic cups were visualized by F-actin staining (center panel). Yellow indicates co-localization of FBP17 (green) and F-actin, phagocytic cups (red) (right panel). The bar is 10 μm.

Phagocytosis of bacterial pathogens is one of the most important primary host defense mechanisms against infections. The phagocytic cup (see Fig. 1B) is an actin-based membrane structure formed at the plasma membrane of phagocytes, including macrophages, upon stimulation with foreign materials such as bacteria. The phagocytic cup captures and ingests foreign materials, and its formation is an essential first step in phagocytosis leading to the digestion of foreign materials (6, 7). When macrophages are stimulated by foreign materials, podosomes disappear, and phagocytic cups, which are also rich in F-actin, are formed to ingest the foreign materials (see Fig. 1D).

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is an X chromosome-linked immunodeficiency disorder. Patients with WAS suffer from severe bleeding, eczema, recurrent infection, autoimmune diseases, and an increased risk of lymphoreticular malignancy (8–10). The causative gene underlying WAS encodes Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) (11). WASP deficiency due to the mutation or deletion causes defects in adhesion, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and the development of hematopoietic cells in WAS patients (10).

The formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups is severely affected in macrophages from WAS patients (3, 12, 42), suggesting that WASP is involved in the formation of these structures. However, the detailed molecular mechanisms of their formation remain unknown. WASP is complexed with a cellular WASP-interacting partner, WASP-interacting protein (WIP) (13, 14). Recently, two groups (including us) have demonstrated that WASP and WIP form a complex and that the WASP-WIP complex is required for the formation of podosomes (4, 15) and phagocytic cups (16). Here, we identified formin-binding protein 17 (FBP17) as a protein interacting with the WASP-WIP complex and examined the role of FBP17 in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies—Recombinant human macrophage-colony stimulating factor-1 (M-CSF-1) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, leupeptin, pepstain A, aprotinin, IGEPAL CA-630, paraformaldehyde, saponin, bovine serum albumin, 3-methyladenine, latex beads (3 μm in diameter), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), human IgG, glycerol, Triton X-100, anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (M2), and anti-β-actin antibody were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The anti-WASP monoclonal antibody, anti-WIP polyclonal antibody, and anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (9E10) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti-dynamin-2 antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences. The rat anti-hemagglutinin (HA) monoclonal antibody (3F10) was purchased from Boehringer Ingelheim (Ridgefield, CT). The Cy2-labeled anti-rat IgG was obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA).

Yeast Two-hybrid Screening—We screened a human lymphocyte cDNA library (Origene Technology Inc., Rockville, MD) using a full-length WIP as bait. A cDNA encoding full-length WIP was cloned into pGilda (BD Biosciences Clontech). The EGY48 yeast strain was transformed with pGilda-WIP, the human lymphocyte cDNA library, and pSH18–34, a reporter plasmid for the β-galactosidase assay. Transformants were assayed for Leu prototrophy, and a filter assay was performed for β-galactosidase measurement (17).

Cells and Transfection—THP-1 and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in RPMI1640 and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's high glucose medium (Invitrogen), respectively, both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. For human primary monocyte isolation, 10–30 ml of peripheral blood was drawn from healthy volunteers and WAS patients after informed consent was obtained. Monocytes were prepared from peripheral blood samples (10–30 ml) using a monocyte isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotech Inc., Auburn, CA). Transfection of THP-1 cells and monocytes was performed with a Nucleofector device using a cell line Nucleofector kit V and a human monocyte Nucleofector kit, respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD). Transfection of HEK293 cells was performed using SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). THP-1 cells and monocytes were co-transfected with the FBP17 constructs and a GFP-expressing plasmid, pmaxGFP (Amaxa Biosystems Inc.), as a transfection marker. The transfection efficiency measured using pmaxGFP was 40–50% for THP-1 cells and 10–20% for monocytes.

RNA Interference—A short interfering RNA (siRNA) for FBP17 and its scrambled control siRNA was synthesized by Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). The targeting sequence was 5′-CCCACTTCATATGTCGAAGTCTGTT-3′ (18). THP-1 cells and monocytes were transfected with siRNA using a cell line Nucleofector kit V and a human monocyte Nucleofector kit, respectively, and a Nucleofector device. Cells were co-transfected with an fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated control siRNA, BLOCK-IT (Invitrogen), as a transfection marker. The transfection efficiency measured using BLOCK-IT was 40–50% for THP-1 cells and 10–20% for monocytes.

Immunoprecipitation—For immunoprecipitation of WASP from THP-1 cells, 2 × 107 cells were lysed in buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 75 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 μg/ml aprotinin). Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was incubated with 2 μg/ml anti-WASP monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 °C for 2 h and then incubated with anti-mouse IgG agarose (Sigma). The resin binding the immune complex was washed three times with 0.5 ml of buffer B (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100), and the complex was eluted with 1× Laemmli's SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Eluted proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting for WASP, WIP, and FBP17.

GST Pull-down Assay—Glutathione S-transferase (GST) and a fusion protein of GST and the src homology 3 (SH3) domain of FBP17 (548–609 amino acids) (GST-FSH3) were purified from Escherichia coli (XL-1B) extracts using glutathione-Sepharose-4B. HEK293 cells were transfected with the cDNAs of Myc- or FLAG-tagged protein and lysed in buffer A. Lysates from the transfected cells were incubated with the affinity matrices of GST alone or GST-FSH3 at 4 °C for 1 h. After a 1-h incubation, the matrices were washed five times with buffer A, and pull-down samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Myc or anti-FLAG antibody.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy—THP-1 cells and monocytes grown on coverslips were differentiated into macrophages by incubation with 12.5 ng/ml PMA (Sigma) and 20 ng/ml M-CSF-1 (R&D Systems), respectively, for 72 h. HEK293 cells were transfected with various cDNA constructs and then cultured on coverslips for 48 h. Cells were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% (w/v) saponin, and blocked with 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin. Cells were stained with primary antibodies and Alexa Fluor 488- or Alexa Fluor 564-labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Cells were also stained with Alexa Fluor 568-labeled phalloidin (Invitrogen). Cell staining was examined under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan AR) or an MRC 1024 SP laser point scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad).

Assays for the Formation of Podosomes and Phagocytic Cups—The formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups was assayed by visualizing these actin-based membrane structures by F-actin staining as described previously (4, 16). Briefly, podosomes in differentiated THP-1 cells or macrophages were visualized by F-actin staining with Alexa Fluor 568-phalloidin. To form phagocytic cups in differentiated THP-1 cells or macrophages, latex beads (3 μm, Sigma) were opsonized with 0.5 mg/ml human IgG (Sigma), and cells grown on coverslips were incubated with the IgG-opsonized latex beads at 37 °C for 10 min in the presence of 10 mm 3-methyladenine (Sigma) to stabilize the phagocytic cups (16). The phagocytic cups were then also visualized with Alexa Fluor 568-phalloidin. Cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioplan AR).

Assays for Macrophage Migration and Phagocytosis—For the macrophage migration assay, human macrophages (2 × 105 cells) were plated onto chemotaxis membranes with 5-μm pores (Corning, Acton, MA) coated with 0.15% gelatin/phosphate-buffered saline placed within Boyden chamber inserts. M-CSF-1 was used as a chemoattractant and diluted in serum-containing RPMI 1640 medium in lower chambers. After a 4-h incubation, non-migrating cells were removed by gently wiping the upper surface of the filter. The filter was removed from the inserts using a razor blade and mounted onto glass plates, and the number of migrating cells was counted under a fluorescence microscope. For the phagocytosis assay, human macrophages (1 × 106 cells) were seeded on coverslips and incubated with 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium containing IgG-opsonized latex beads (3 μm) at 4 °C for 10 min, allowing the beads to attach to cells. Phagocytosis was initiated by adding 1.5 ml of preheated RPMI 1640 medium, and the cells were incubated with the beads at 37 °C for 30 min. Control plates were incubated at 4 °C to estimate nonspecific binding of latex beads to the cells. After incubation, the cells were vigorously washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and the number of intracellular latex beads was determined by counting beads within cells under a fluorescence microscope. The percentage of phagocytosis was calculated as the total number of cells with at least one bead as a percentage of the total number of cells counted. At least 100 cells were examined.

Cell Fractionation—To prepare the cytoplasmic and membrane fractions, macrophages (1 × 106 cells) were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and suspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 1 mm EDTA and proteinase inhibitors as described above. The cell suspensions were sonicated four times on ice for 5 s each using a bath-type sonicator followed by ultracentrifugation at 265,000 × g at 4 °C for 2 h. The supernatant was used as the cytosolic fraction, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 1 mm EDTA and used as the membrane fraction. Anti-Caspase-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-sodium potassium ATPase antibodies (AbCam, Inc., Cambridge, MA) were used to determine the purity of the cytosolic and membrane fractions, respectively.

Statistics—Statistically significant differences were determined using the Student's t test. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05.

RESULTS

FBP17 Binds to the WASP-WIP Complex and Dynamin-2 in Macrophages—To explore the detailed molecular mechanisms of the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups, we searched for a protein interacting with the WASP-WIP complex. We identified FBP17 as a WIP-binding protein in a yeast two-hybrid screen using the full-length WIP as bait. FBP17 was originally identified as a protein binding to formin, a protein that regulates the actin cytoskeleton (19). FBP17 is a member of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe Cdc15 homology (PCH) protein family (20) and contains an N-terminal extended FER-CIP4 homology (EFC) domain (also known as the FER-CIP4 homology and Bin-amphiphysin-Rvs (F-BAR) domain), protein kinase C-related kinase homology region 1 (HR1), and an SH3 domain (Fig. 1E). The EFC/F-BAR domain has membrane binding and deformation activities, and FBP17 is involved in endocytosis in transfected COS-7 cells (18, 21, 22).

To confirm that FBP17 directly interacts with WIP or WASP, we performed GST pull-down assays using a fusion protein of GST and the SH3 domain of FBP17 (GST-FBPSH3). Purified GST and the GST-FSH3 fusion protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1F, lanes 1 and 2). The HEK293 transfected cells express the Myc- and FLAG-tagged proteins (Fig. 1F, lanes 3–6). The results from the GST pull-down assays were shown (Fig. 1F, lanes 7–14). Both WASP and WIP were pulled down by GST-FSH3 (Fig. 1, lanes 10 and 14), indicating that the SH3 domain of FBP17 directly interacts with both proteins.

It has previously been shown that FBP17 binds to N-WASP and dynamin in transfected cells (18, 21). We examined whether FBP17 binds to WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 in macrophages. THP-1 (human monocyte cell line) cells closely resemble monocyte-derived macrophages when differentiated by stimulation with PMA (23) and form podosomes and phagocytic cups that are morphologically and functionally indistinguishable from those in primary macrophages (supplemental Fig. 1) (4, 16, 23). WASP was immunoprecipitated from the lysates of PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells with an anti-WASP monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1G, lanes 2, 5, and 8) followed by immunoblotting using antibodies to FBP17 (21), WASP, and WIP. Both WIP and FBP17 co-immunoprecipitated with WASP (Fig. 1G, lanes 5 and 8). FBP17 also co-immunoprecipitated with dynamin-2 (Fig. 1G, lanes 14). These results, taken together with the results in Fig. 1F, suggest that FBP17 binds to the WASP-WIP complex and dynamin-2 in macrophages.

We next used immunofluorescence to examine whether FBP17 localizes at podosomes and phagocytic cups because the WASP-WIP complex is an essential component of podosomes (4, 15) and phagocytic cups (16). THP-1 cells transfected with FLAG-tagged FBP17 (FLAG-FBP17) and differentiated by stimulation with PMA were stained with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody to visualize FBP17 and with phalloidin to visualize the F-actin in podosomes and phagocytic cups (Fig. 1, H and I, left and middle panels). Merged images revealed that both F-actin and FBP17 are present in podosomes and phagocytic cups (Fig. 1, H and I, right panels), indicating that FBP17 localizes at podosomes and phagocytic cups.

Importance of FBP17 in the Formation of Podosomes and Phagocytic Cups—To determine the importance of FBP17 in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups, we knocked down FBP17 in THP-1 cells with siRNAs. To confirm that the expression of FBP17 was knocked down in cells, we transfected THP-1 cells with siRNAs, prepared lysates from the total siRNAs-transfected cells, and analyzed the expression level of FBP17 by immunoblotting. THP-1 cells transfected with the siRNA for FBP17 expressed ∼40% less FBP17 than cells transfected with a scrambled control siRNA based on the immunoblots (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2) but expressed the same level of β-actin (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4). The transfection efficiency of THP-1 cells was estimated to be 40–50% from the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) used as a transfection control. Therefore, the decrease in FBP17 expression indicates that FBP17 was efficiently knocked down in most transfected cells.

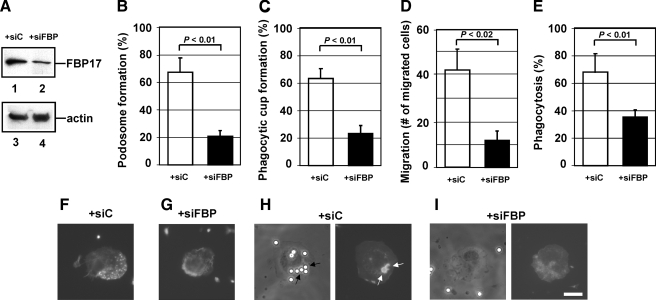

FIGURE 2.

The importance of FBP17 in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. A, expression of FBP17 was reduced by transfection of siRNA. THP-1 cells were transfected with siRNA for FBP17 (siFBP; lanes 2 and 4) or its scrambled control siRNA (siC; lanes 1 and 3). Lysates prepared from total transfected cells were analyzed by immunoblotting for FBP17 (lanes 1 and 2) and β-actin (lanes 3 and 4). B and C, effects of FBP17 siRNA on the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups in macrophages. Human primary monocytes were co-transfected with siFBP (closed bars) or siC (open bars) and an FITC-conjugated control siRNA and then differentiated into macrophages with M-CSF-1. FITC-positive transfected cells were examined for the formation of podosomes (B) or phagocytic cups (C), and the percentage of cells with podosomes or phagocytic cups was scored. D and E, effects of FBP17 siRNA on the functions of podosomes and phagocytic cups. Macrophages co-transfected with siFBP (closed bars) or siC (open bars) and the FITC-conjugated control siRNA were assayed for macrophage migration (D) or phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized latex beads (E). Data represent the mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments. F–I, immunofluorescence micrographs of a representative cell from each experiment. Cells transfected with siC (F) and siFBP (G) were stained with Alexa Fluor 568-phalloidin. Cells transfected with siC (H) or siFBP (I) were incubated with IgG-opsonized latex beads and then stained with phalloidin. The left and right panels are phase contrast and immunofluorescence micrographs, respectively. The bar is 10 μm.

Human primary monocytes were co-transfected with the FBP17 siRNAs and a FITC-conjugated control siRNA as a transfection marker. After differentiation of the monocytes into macrophages with M-CSF-1, FITC-positive cells were examined for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. To quantify their formation, we scored the percentage of cells with podosomes or phagocytic cups among FITC-positive cells. When the expression of FBP17 was knocked down, the formation of both podosomes and phagocytic cups in macrophages was significantly reduced (p < 0.01; Fig. 2, B and C). These results suggest that FBP17 is necessary for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. A representative cell from each experiment is shown in Fig. 2, F and G, for podosomes and in Fig. 2, H and I, for phagocytic cups. We then assayed macrophage migration as a podosome function and phagocytosis as a phagocytic cup function. When expression of FBP17 was knocked down, macrophage migration through a gelatin filter toward a chemoattractant was significantly reduced in cells transfected with FBP17 siRNA (p < 0.02; Fig. 2D). Phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized latex beads was also reduced (Fig. 2E). These results suggest that FBP17 is essential for chemotaxis and phagocytosis because of its role in forming podosomes and phagocytic cups, respectively.

FBP17 Recruits the WASP-WIP Complex to the Plasma Membrane—Recent biochemical analyses revealed that FBP17 binds to a membrane phospholipid, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), through its EFC/F-BAR domain and to N-WASP and dynamin via its SH3 domain (18, 21, 24). We have shown that although WASP and WIP are cytosolic proteins, the WASP-WIP complex localizes at podosomes and phagocytic cups (4, 16). We then examined whether FBP17 recruits the WASP-WIP complex to the plasma membrane in macrophages. We focused on the roles of the EFC and SH3 domains of FBP17 and constructed three FBP17 mutants for the recruitment experiments: a Lys-33 to Glu (K33E) substitution, a Lys-166 to Ala (K166A) substitution, and an SH3 domain deletion (dSH3). Both substitution mutations in the EFC domain (K33E and K166A) significantly reduce membrane binding and deformation (22), and the dSH3 mutant does not bind to WASP and WIP because the SH3 domain is the binding site of WASP and WIP (Fig. 1F). We co-transfected HEK293 cells with the FLAG-tagged FBP17 constructs, WASP, and WIP. A C-terminal fragment (1146–1429 amino acids) of PDZ-GDP exchange factor (PDZ-GEF) was used as a negative control for FBP17 because this fragment is stable in the cytosol and does not interact with any WASP-related proteins (4, 16, 25). We confirmed the expression of FBP17 and its mutants in cells by immunoblotting (supplemental Fig. 2) and immunoprecipitated FLAG-tagged proteins from lysates of the transfected cells with anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 3A, lanes 1–5). WASP and WIP were detected in the immunoprecipitates from cells expressing the FLAG-tagged FBP17, K33E, and K166A constructs (Fig. 3A, lanes 7–9 and 12–14) but not the FLAG-tagged PDZ-GEF and dSH3 constructs (Fig. 3A, lanes 6, 10, 11, and 15), indicating that FBP17 and its mutants K33E and K166A form a complex with WASP and WIP but that dSH3 not.

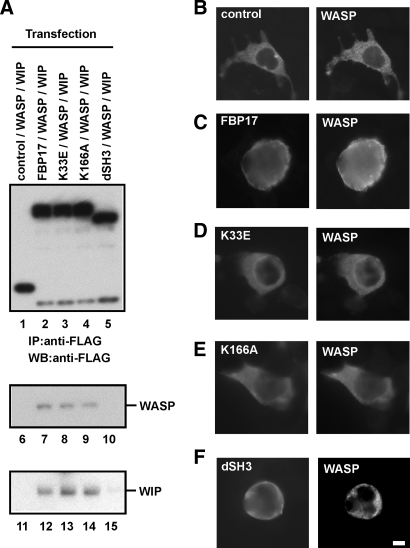

FIGURE 3.

FBP17 recruits WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 to the plasma membrane. A, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with cDNAs of the indicated FLAG-tagged proteins, Myc-tagged WASP, and HA-tagged WIP. The FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) from lysates of the transfected cells with an anti-FLAG antibody followed by immunoblotting (WB) using antibodies to FLAG (lanes 1–5), WASP (lanes 6–10), and WIP (lanes 11–15). B–F, transfected HEK293 cells expressing FLAG-tagged proteins, Myc-WASP, and HA-WIP were double-stained with an anti-FLAG antibody and anti-WASP antibody. B–F, cells expressing FLAG-PDZ-GEF (B), FLAG-FBP17 (C), the FLAG-tagged FBP17 mutant with the K33E missense mutation (D), K166A (E), and the SH3-deleted FBP17 mutant dSH3 (F). The bar is 10 μm.

Next, cells expressing the FLAG-tagged proteins, WASP, and WIP were examined under the immunofluorescence microscope for the localization of the FLAG-tagged proteins and WASP. WASP and WIP were localized in the cytosol in cells transfected with only the WASP cDNA and only the WIP cDNA, respectively, as well as in cells expressing both WASP and WIP (supplemental Fig. 3). In cells co-expressing FLAG-PDZ-GEF (control) with WASP and WIP, both FLAG-PDZ-GEF and WASP were cytosolic (Fig. 3B). In cells co-expressing FLAG-FBP17 with WASP and WIP, FLAG-FBP17 localized at the plasma membrane because its EFC domain binds to the plasma membrane (Fig. 3C, left panel). In those cells, WASP also localized at the plasma membrane (Fig. 3C, right panel), indicating that FBP17 shifted the localization of WASP from the cytosol to the plasma membrane (Fig. 3, B and C). To confirm that the WASP-WIP complex was recruited to the plasma membrane, cells co-expressing FLAG-FBP17 with WASP and HA-tagged WIP were stained with an anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody and an anti-WASP polyclonal antibody or an anti-HA rat monoclonal antibody. Double staining revealed that both WASP and WIP co-localized with FLAG-FBP17 at the plasma membrane (supplemental Fig. 4, A and B). To further confirm the localization of the FBP17 mutants, cells co-expressing the FLAG-tagged FBP mutants, WASP, and WIP were stained with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody. The K33E and K166A mutants were cytosolic and the SH3-deleted FBP17 mutant localized at the plasma membrane (supplemental Fig. 4C).

To determine the roles of the EFC and SH3 domains of FBP17 in this recruitment, we examined the localization of the FBP17 mutants and WASP in cells co-expressing the FBP mutants with WASP and WIP. Membrane tubulation in cells transfected with an FBP17 cDNA is an indicator of the membrane binding and deformation activities of FBP17 (18, 22). We detected in vivo membrane tubulation in cells expressing FBP17 and dSH3 but not in cells expressing K33E and K166A (supplemental Fig. 5). In cells co-expressing either FBP17 mutant (K33E or K166A) with WASP and WIP, both K33E and K166A were cytosolic (Fig. 3, D and E, left panels), and WASP was also cytosolic (Fig. 3, D and E, right panels). These results indicate that K33E and K166A are unable to recruit WASP to the plasma membrane, consistent with the inability of K33E and K166A to bind and deform the plasma membrane (supplemental Fig. 5).

The SH3-deleted FBP17 mutant, dSH3, localized at the plasma membrane (Fig. 3F, left panel) because its EFC domain is intact. However, WASP was cytosolic in cells co-expressing dSH3 with WASP and WIP (Fig. 3F, right panel), consistent with the inability of the dSH3 mutant to bind to WASP and WIP (Fig. 3A, lanes 5, 10, and 15).

To quantify the recruitment, we scored the percentage of cells in which WASP and WIP were localized at the plasma membrane. Cells expressing the FBP17 mutants (K33E, K166A, or dSH3) exhibited significantly lower plasma membrane localization of WASP and WIP than cells expressing FBP17 (p < 0.05; supplemental Fig. 6, A and B). FBP17 also recruited dynamin-2 to the plasma membrane, and both EFC and SH3 domains are necessary for this recruitment (supplemental Fig. 6C), as reported previously (18, 21). To confirm the localization of FBP17 and its mutants in cells co-expressing FBP17 with WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2, the transfected cells were stained with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody. The wild-type FBP17 and dSH3 localized at the plasma membrane and the FLAG-PDZ-GEF (control) and the FBP mutants (K33E and K166A) were cytosolic (supplemental Fig. 6D).

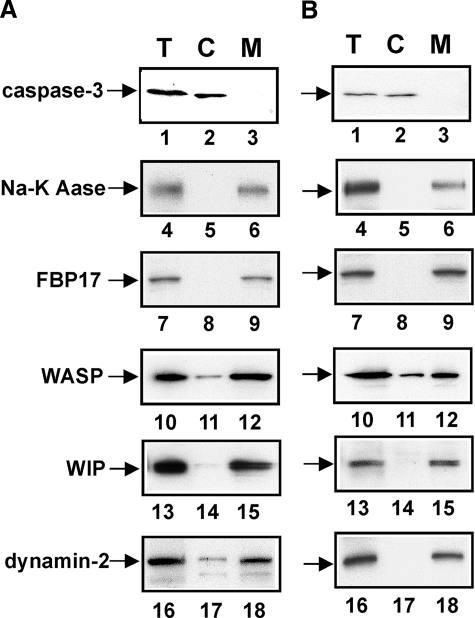

Subcellular Localization of FBP17, WASP, WIP, and Dynamin-2 in Macrophages—To determine whether WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 are recruited to the plasma membrane in macrophages when podosomes and phagocytic cups are formed, we examined the subcellular localization of FBP17, WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 in macrophages forming podosomes or phagocytic cups. The cytosolic and membrane fractions were prepared from macrophages and analyzed by immunoblotting. Caspase-3 is a cytosolic marker, and sodium potassium ATPase is a plasma membrane marker (26). FBP17 was detected in the membrane fraction from macrophages forming podosomes (Fig. 4A, lane 9). WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 were also detected in the membrane fraction, although they are cytosolic proteins (Fig. 4A, lanes 12, 15, and 18). FBP17 was detected in the membrane fraction from macrophages forming phagocytic cups (Fig. 4B, lane 9). WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 were also detected in the membrane fractions from macrophages forming phagocytic cups (Fig. 4B, lanes 12, 15, and 18). These results, taken together with Fig. 3, suggest that FBP17 recruits the WASP-WIP complex and dynamin-2 to the plasma membrane in macrophages and that both the EFC and the SH3 domains are necessary for this recruitment.

FIGURE 4.

Subcellular localization of FBP17, WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 in macrophages. A, macrophages forming podosomes. B, macrophages forming phagocytic cups. Total lysates (T), the cytosolic fraction (C), and the membrane fraction (M) prepared from macrophages forming podosomes (A) or phagocytic cups (B) were analyzed by immunoblotting for caspase-3 (lanes 1–3), sodium potassium ATPase (Na-K Aase; lanes 4–6), FBP17 (lanes 7–9), WASP (lanes 10–12), WIP (lanes 13–15), and dynamin-2 (lanes 16–18). Caspase-3 and sodium potassium ATPase (Na-K ATPase) are markers for the cytosol and plasma membrane, respectively.

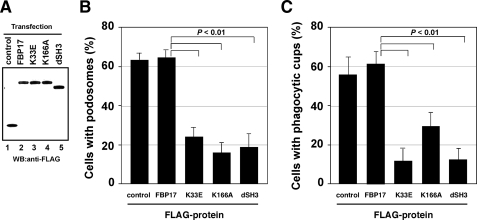

The Role of Each Domain of FBP17 in the Formation of Podosomes and Phagocytic Cups—To determine the roles of the EFC and SH3 domains in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups, we examined whether overexpression of the FBP17 mutants affects the formation of these structures. We transfected THP-1 cells with the FBP17 constructs and confirmed the expression of FBP17 or the FBP17 mutants in transfected THP-1 cells by immunoblotting (Fig. 5A). When THP-1 cells were differentiated to obtain macrophage phenotypes with PMA, podosome formation was significantly reduced in cells overexpressing the K33E, K166A, and dSH3 FBP17 mutants when compared with the FBP17 wild type (p < 0.01; Fig. 5B). Phagocytic cup formation was also reduced in cells overexpressing the FBP17 mutants (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that the EFC domain and SH3 domain are essential for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups in macrophages.

FIGURE 5.

The role of the EFC and SH3 domains of FBP17 in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. A, expression of FLAG-tagged proteins in transfected THP-1 cells. Total lysates prepared from transfected THP-1 cells were analyzed by immunoblotting (WB) using an anti-FLAG antibody. All of the FLAG-tagged proteins, FLAG-PDZ-GEF (control, lane 1), FLAG-FBP17 (lane 2), and the FBP17 mutants, K33E, K166A, and dSH3 (lanes 3–5) were expressed in THP-1 cells at similar levels. B and C, THP-1 cells co-transfected with cDNAs for the FLAG-tagged proteins and pmaxGFP were differentiated with PMA and then assayed for the formation of podosomes (B) and phagocytic cups (C). The percentage of cells with podosomes or phagocytic cups among all GFP-positive cells was scored. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of triplicate experiments.

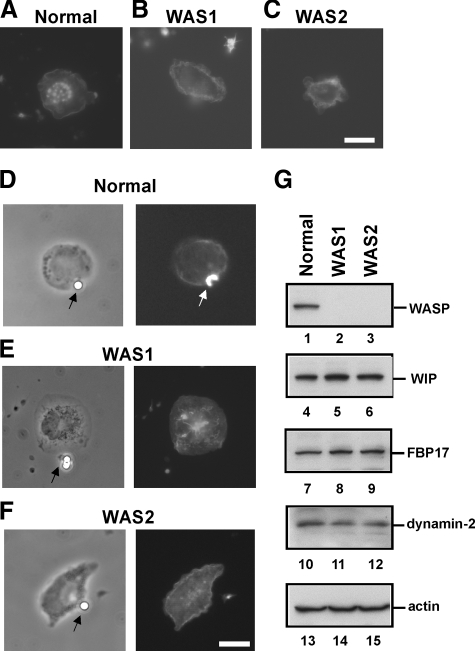

Defects in Macrophages from WAS Patients—Our results suggest that the complex formation of FBP17 with WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 at the plasma membrane is a critical step in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups (Figs. 1G, 3, and 4). In macrophages from WASP-deficient WAS patients, the complex does not form properly due to a lack of WASP expression. We examined macrophages from WASP-deficient WAS patients for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. Two genetically independent WAS patients (WAS1, 211delT; and WAS2, 41–45delG) (27, 28) were assayed for the formation of those structures. Podosomes were completely absent (Fig. 6, A–C), and phagocytic cup formation was severely impaired (Fig. 6, D–F) in macrophages from both WAS patients, although FBP17, WIP, and dynamin-2 were expressed at the same level in patients as in normal individuals (Fig. 6G). In fact, the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups was impaired in macrophages when the expression of WASP was reduced by siRNA transfection (4, 16). This is the first result showing that both podosome and phagocytic cup formations are defective in macrophages from WASP-deficient patients. These results are consistent with the previous observations (3, 12). These results give us a natural example that supports the importance of the complex formation of FBP17 with WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups.

FIGURE 6.

Defective formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups in macrophages from WAS patients. A–F, macrophages from a normal control and two genetically independent WAS patients (WAS1 and WAS2) were examined for the formation of podosomes (A–C) and phagocytic cups (D–F). The patients, WAS1 and WAS2, have the deletion mutations 211delT and 41–45delG, respectively, in their genomic DNAs. The bars are 10 μm. G, expression levels of WASP, WIP, FBP17, dynamin-2, and β-actin in WAS patients. Lysates prepared from macrophages from a normal control and two WAS patients (WAS1 and WAS2) were subjected to immunoblotting. WASP was not detected in the lysates from these WAS patients (lanes 2 and 3). Podosomes were completely absent (A–C) and phagocytic cup formation was severely impaired (D–F) in macrophages from both WAS patients, although FBP17, WIP, and dynamin-2 were expressed at the same level in patients as in normal individuals (G) (lanes 4–12).

DISCUSSION

Cell biological and structural analyses of the EFC domain of FBP17 have shown that the EFC domain binds to and deforms the plasma membrane (18, 22). It has previously been shown that the SH3 domain of FBP17 binds to N-WASP and dynamin in transfected cells (18, 21). However, physiologically important processes to which those activities of FBP17 contribute were unknown. Here, we have demonstrated that FBP17 recruits the WASP-WIP complex from the cytosol to the plasma membrane and that this recruitment is necessary for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups in macrophages. Our results suggest that FBP17 facilitates membrane deformation and actin polymerization induced by the WASP-WIP complex to occur simultaneously at the same membrane sites and that both are required for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups. This is supported by the observations that regulated actin polymerization is an essential process for the formation of podosomes (3) and phagocytic cups (29). Thus, FBP17 mediates a common molecular step in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups.

Macrophages have the ability to form both podosomes and phagocytic cups (Fig. 1, A–D). When macrophages having podosomes are stimulated with IgG-opsonized latex beads, the podosomes immediately disappear, and the phagocytic cups are formed at the site that the IgG beads attach. This observation indicates that the transition of the membrane structures occurs from podosomes to phagocytic cups. Macrophages migrate to sites of inflammation where they phagocytose pathogenic microbes and damaged tissue compounds and mediate local effector functions. Once macrophages encounter those materials at the site of inflammation, they stop migrating and phagocytose those materials. The transition of the macrophage functions occur from migration to phagocytosis. Podosomes and phagocytic cups are the essential membrane structures for migration and phagocytosis, respectively. Thus, the transition of the membrane structures from podosomes to phagocytic cups is essential and significant for the transition of the macrophage functions. Recently, two reports suggest that macrophage migration and phagocytosis include a common molecular mechanism to regulate actin cytoskeleton (40, 41). In this study, we identified a critical common molecular step mediated by FBP17 for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups, which are essential for migration and phagocytosis, respectively. In the future, elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the transition would be intriguing.

It has been reported that dynamin-2 is also required for the formation of podosomes in transformed cells and osteoclasts (30–32) and phagocytic cups in a mouse macrophage cell line (33, 34) and that the FBP17-dynamin complex regulates the plasma membrane invagination (35). Our results suggest that FBP17 recruits dynamin-2 to the same site as membrane deformation and that this recruitment is also necessary for the formation of these structures (Figs. 3, 4, 5 and supplemental Fig. 6C). The formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups involves the process of the membrane protrusion (Fig. 1, A–D). The membrane protrusion requires the delivery of new membrane material (2). Our results, taken together with the above observations, suggest that dynamin-2 recruited by FBP17 to the plasma membrane probably plays an essential role in the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups by regulating the recruitment of vesicles to the plasma membrane as new membrane material in macrophages.

Recently, the EFC domain of FBP17 was shown to bind strongly to the PI(4,5)P2 (18, 22). On the other hand, it has been shown that PI(4,5)P2 localizes at the podosomes in osteoclasts (36) and phagocytic cups (37, 38). These observations suggest that PI(4,5)P2 is synthesized upon stimulation at the plasma membrane and plays an important role in the recruitment of FBP17 to the plasma membrane. Presumably, the PI(4,5)P2 binding activity of the EFC domain is necessary for the localization of FBP17, and therefore, of the WASP-WIP complex and dynamin-2, at the sites where podosomes and phagocytic cups will form.

We suggest that the complex formation of FBP17 with WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 at the plasma membrane is critical for the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups (Figs. 1G and 3, 4, 5). In macrophages from WASP-deficient WAS patients, defects in the complex formation of FBP17 with WASP, WIP, and dynamin-2 impair the formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups (WAS1: 211delT (27); WAS2: 41–45delG(28) in Fig. 6), thereby reducing chemotaxis and phagocytosis by macrophages, which in turn would decrease the ability of host defense. The severity of WAS-associated symptoms was estimated and expressed as a score of 1–5. A score of 1 was assigned to patients with only thrombocytopenia and small platelets, and a score of 2 was assigned to patients with additional findings of mild, transient eczema or minor infections. Those with treatment-resistant eczema and recurrent infections despite optimal treatment received a score of 3 (mild WAS) or 4 (severe WAS). Regardless of the original score, if any patients then had autoimmune disease or malignancy, the score was changed to 5. The patients, WAS1 and WAS2, receive scores of 5 and 4, respectively. Both patients have the recurrent infections. We suggest that defective formation of podosomes and phagocytic cups in their macrophages (Fig. 6, A–F) reduces chemotaxis and phagocytosis, which are the critical processes to protect the body against infection, resulting in the recurrent infections. In addition, defective phagocytosis reduces the clearance of self-antigens such as apoptotic cells. This may cause the autoimmune diseases seen in WAS patients. In fact, Cohen et al. (39) recently reported that reduced clearance of apoptotic cells resulted in development of autoimmunity. Our findings therefore provide a potential mechanism for the recurrent infections and autoimmune diseases seen in WAS patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Fukuda, R. C. Liddington, S. Courtneidge, A. Strongin (Burnham Institute for Medical Research), S. Grinstein (Hospital for Sich Children, Ontario, Canada), J. Condeelis (Albert Einstein Medical College), and P. De Camilli (Yale University) for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussion.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01HD042752 (to S. T.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains six supplemental figures.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: M-CSF-1, macrophage-colony stimulating factor-1; FBP17, formin-binding protein 17; WAS, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome; WASP, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein; N-WASP, neuronal WASP; WIP, WASP interacting-protein; EFC domain, extended FER-CIP4 homology domain; F-BAR domain, FER-CIP4 homology and Bin-amphiphysin-Rvs domain; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; GFP, green fluorescence protein; siRNA, short interfering RNA; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PDZ-GEF, PDZ-guanine nucleotide exchange factor; HEK293 cells, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; HA, hemagglutinin; SH3, src homology 3 domain; dSH3, SH3 domain deletion; GST, glutathione S-transferase;, PI(4,5)P2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; siFBP, siRNA for FBP17; siC, scrambled control siRNA.

References

- 1.Linder, S., and Aepfelbacher, M. (2003) Trends Cell Biol. 13 376-385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linder, S. (2007) Trends Cell Biol. 17 107-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linder, S., Nelson, D., Weiss, M., and Aepfelbacher, M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 9648-9653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuboi, S. (2007) J. Immunol. 178 2987-2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carman, C. V., Sage, P. T., Sciuto, T. E., Fuente, M. A. d. l., Geha, R. S., Ochs, H. D., Dvorak, H. F., Dvorak, A. M., and Springer, T. A. (2007) Immunity 26 784-797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Underhill, D. M., and Ozinsky, A. (2002) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20 825-852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leverrier, Y., and Ridley, A. J. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11 195-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiskott, A. (1937) Monatsschr. Kinderheilkd. 68 212-216 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldrich, R. A., Steinberg, A. G., and Campbell, D. C. (1954) Pediatrics 13 133-139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Notarangelo, L. D., Miao, C. H., and Ochs, H. D. (2008) Curr. Opin. Hematol. 15 30-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derry, J. M., Ochs, H. D., and Francke, U. (1994) Cell 78 635-644; Correction (1994) Cell 79, 9228069912 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenzi, R., Brickell, P. M., Katz, D. R., Kinnon, C., and Thrasher, A. J. (2000) Blood 95 2943-2946 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramesh, N., Anton, I. M., Hartwig, J. H., and Geha, R. S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 14671-14676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anton, I. M., de la Fuente, M. A., Sims, T. N., Freeman, S., Ramesh, N., Hartwig, J. H., Dustin, M. L., and Geha, R. S. (2002) Immunity 16 193-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou, H. C., Anton, I. M., Holt, M. R., Curcio, C., Lanzardo, S., Worth, A., Burns, S., Thrasher, A. J., Jones, G. E., and Calle, Y. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16 2337-2344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuboi, S., and Meerloo, J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 34194-34203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuboi, S., Nonoyama, S., and Ochs, H. D. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7 506-511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsujita, K., Suetsugu, S., Sasaki, N., Furutani, M., Oikawa, T., and Takenawa, T. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 172 269-279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan, D. C., Bedford, M. T., and Leder, P. (1996) EMBO J. 15 1045-1054 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho, H. Y., Rohatgi, R., Lebensohn, A. M., Le, M., Li, J., Gygi, S. P., and Kirschner, M. W. (2004) Cell 118 203-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamioka, Y., Fukuhara, S., Sawa, H., Nagashima, K., Masuda, M., Matsuda, M., and Mochizuki, N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 40091-40099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada, A., Niwa, H., Tsujita, K., Suetsugu, S., Nitta, K., Hanawa-Suetsugu, K., Akasaka, R., Nishino, Y., Toyama, M., Chen, L., Liu, Z. J., Wang, B. C., Yamamoto, M., Terada, T., Miyazawa, A., Tanaka, A., Sugano, S., Shirouzu, M., Nagayama, K., Takenawa, T., and Yokoyama, S. (2007) Cell 129 761-772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auwerx, J. (1991) Experientia (Basel) 47 22-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kakimoto, T., Katoh, H., and Negishi, M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 29042-29053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rebhun, J. F., Castro, A. F., and Quilliam, L. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 34901-34908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takayama, S., Krajewski, S., Krajewska, M., Kitada, S., Zapata, J. M., Kochel, K., Knee, D., Scudiero, D., Tudor, G., Miller, G. J., Miyashita, T., Yamada, M., and Reed, J. C. (1998) Cancer Res. 58 3116-3131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin, Y., Mazza, C., Christie, J. R., Giliani, S., Fiorini, M., Mella, P., Gandellini, F., Stewart, D. M., Zhu, Q., Nelson, D. L., Notarangelo, L. D., and Ochs, H. D. (2004) Blood 104 4010-4019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imai, K., Morio, T., Zhu, Y., Jin, Y., Itoh, S., Kajiwara, M., Yata, J., Mizutani, S., Ochs, H. D., and Nonoyama, S. (2004) Blood 103 456-464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.May, R. C., Caron, E., Hall, A., and Machesky, L. M. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2 246-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochoa, G. C., Slepnev, V. I., Neff, L., Ringstad, N., Takei, K., Daniell, L., Kim, W., Cao, H., McNiven, M., Baron, R., and De Camilli, P. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150 377-389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNiven, M. A., Baldassarre, M., and Buccione, R. (2004) Front. Biosci. 9 1944-1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruzzaniti, A., Neff, L., Sanjay, A., Horne, W. C., De Camilli, P., and Baron, R. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16 3301-3313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gold, E. S., Underhill, D. M., Morrissette, N. S., Guo, J., McNiven, M. A., and Aderem, A. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190 1849-1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tse, S. M., Furuya, W., Gold, E., Schreiber, A. D., Sandvig, K., Inman, R. D., and Grinstein, S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 3331-3338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itoh, T., Erdmann, K. S., Roux, A., Habermann, B., Werner, H., and De Camilli, P. (2005) Dev. Cell 9 791-804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chellaiah, M. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 32930-32943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Botelho, R. J., Teruel, M., Dierckman, R., Anderson, R., Wells, A., York, J. D., Meyer, T., and Grinstein, S. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 151 1353-1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewitt, S., Tian, W., and Hallett, M. B. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 443-451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen, P. L., Caricchio, R., Abraham, V., Camenisch, T. D., Jennette, J. C., Roubey, R. A., Earp, H. S., Matsushima, G., and Reap, E. A. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 196 135-140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandt, D. T., Marion, S., Griffiths, G., Watanabe, T., Kaibuchi, K., and Grosse, R. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 178 193-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato, M., Khan, S., d'Aniello, E., McDonald, K. J., and Hart, D. N. J. (2007) J. Immunol. 179 6052-6063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calle, Y., Anton, I. M., Thrasher, A. J., and Jones, G. E. (2008) J. Microsc. (Oxf.) 231 494-505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.