Abstract

Although much progress has been made toward the identification of innate immune receptors, far less is known about how these receptors recognize specific microbial products. Such studies have been hampered by the need to purify compounds from microbial sources and a reliance on biological assays rather than direct binding to monitor recognition. We have employed surface plasmon resonance (SPR) binding studies using a wide range of well defined synthetic muropeptides derived from Gram-positive (lysine-containing) and Gram-negative (diaminopimelic acid (DAP)-containing) bacteria to demonstrate that Toll-like receptor 2 can recognize peptidoglycan (PGN). In the case of lysine-containing muropeptides, a limited number of compounds, which were derived from PGN remodeled by bacterial autolysins, was recognized. However, a wider range of DAP-containing muropeptides was bound with high affinity, and these compounds were derived from nascent and remodeled PGN. The difference in recognition of the two classes of muropeptides is proposed to be a strategy by the host to respond appropriately to Gram-negative and -positive bacteria, which produce vastly different quantities of PGN. It was also found that certain modifications of the carboxylic acids of isoglutamine and DAP can dramatically reduce binding, and thus, bacterial strains may employ such modifications to evade innate immune detection. Cellular activation studies employing highly purified PGN from Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus plantarum, Micrococcus luteus, and Staphylococcus aureus support the structure binding relationship. The data firmly establish Toll-like receptor 2 as an innate immune sensor for PGN and provides an understanding of host-pathogen interactions at the molecular level.

The innate immune system is an ancient evolutionary system of defense against microbial infections that rapidly responds to highly conserved families of microbial components that are not produced by the host. These so called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)2 include microbial structures such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipoteichoic acid, mannans, flagellin, peptidoglycan (PGN), and DNA sequences containing unmethylated CpG dinucleotides (CpG DNA) (1, 2). The PAMPs are recognized by highly conserved pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), PGN recognition proteins (PGRPs), collectins, and nucleotide binding oligomerization domain (NOD) proteins. Cellular activation by these receptors results in acute inflammatory responses such as the production of diverse sets of cytokines and chemokines, direct local attack against the invading pathogen, and initiation of responses that activate and regulate the adaptive component of the immune response. Although these responses are beneficial for host defense, the presence of a large amount of PAMPs can cause overproduction of the inflammatory mediators, which can lead to septic inflammatory response syndrome and includes life-threatening symptoms such as vascular fluid leakage, tissue damage, hypotension, shock, and organ failure (3, 4).

Although much progress has been made toward the identification of key innate immune receptors, far less is known about how these receptors recognize and initiate responses to specific microbial products. In this respect it is well known that structural variability is considerable among PAMPs of different microbial strains (5–7). Structural variability can be both advantageous and disadvantageous as it offers a microbe a strategy to evade detection by the host innate immune system or presents the host an opportunity to mount a specific and appropriately measured immune response to particular microbial strains. Heterogeneity in the structure of PAMPs within a particular microbial strain and possible contaminations with other inflammatory mediators have made it difficult to identify biological responses initiated by specific PAMPs.

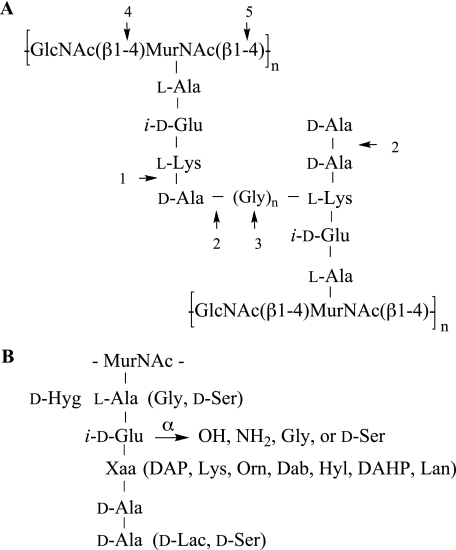

PGN is a highly complex structural component of the cell wall of almost all bacteria that has been implicated as a PAMP in innate immune responses. It is a large and complex polymer composed of alternating β-(1–4)-linked N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid residues cross-linked by peptide bridges (Fig. 1) (6–8). The carboxylic acid of N-acetylmuramic acid is linked to stem peptides consisting of four or five alternating l- and d-amino acids. Among different bacterial species, the structure of the sugar chain is rather conserved, whereas the composition of the stem peptide subunits varies considerably. For example, lysine is commonly the third amino acid of the peptide moieties of PGN of most Gram-positive bacteria, whereas Gram-negative and most rod-shaped Gram-positive bacteria have a diaminopimelic acid (DAP) residue at this position. Furthermore, the α-carboxylate of the iso-d-Glu moiety is often amidated or linked to additional amino acids such as Gly or d-Ser. Considerable heterogeneity has been found in the nature of the interpeptide bridge, which connects the ε-amino group of the lysine or DAP moiety to the penultimate d-Ala of another PGN chain, resulting in the loss of terminal d-Ala.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of PGN. Common primary structure of Gram-positive PGN (A). Sites where autolysins may act are indicated: 1, dl-carboxypeptidase; 2, d,d-carboxypeptidase; 3, endopeptidase; 4, N-acetylglucosaminidase; 5, N-acetylmuramidase. Variations in the peptide chain of PGN (B). Residues in parentheses may replace corresponding amino acids. The α-carboxylic acid of iso-d-Glu may be modified by an amide, Gly, or d-Ser. (Dab, 2,4-diaminobutyric acid; DAHP, 2,6-diamino-3-hydroxypimelic acid; Hyg, threo-3-hydroxyglutamic acid; Hyl, hydroxylysine; Lan, lanthionine; Orn, ornithine).

Additional structural heterogeneity is introduced during bacterial growth and division, which requires remodeling of cell wall PGN by bacterial autolysins such as dd- and dl-carboxypeptidases, endopeptidases, and N-acetylmuramidases. These enzymes cleave peptide and glycosidic linkages to generate muramyl tri- and tetrapeptides, tetrapeptides extended by glycine moieties, and shorter polysaccharide chains (Fig. 1A) (9–11). The remodeling process leads to a loss of PGN fragments to the bloodstream that can be detected by innate immune receptors.

The intracellular NOD receptors (NOD1 and NOD2) can detect small monovalent PGN fragments resulting in the production of (pro)inflammatory mediators (12–15). PGRPs are a relatively new class of pattern recognition receptors that are highly conserved from insects to mammals and can bind or enzymatically process PGN (16, 17). Mammalian PGRPs do not induce inflammatory responses but exert their roles by amidase or antibacterial activity. The involvement of TLR2 in the recognition of PGN for the initiation of inflammatory responses has been controversial (18–20). Furthermore, it is not known which structural elements of PGN can be recognized by TLR2. The involvement of TLR2 in PGN sensing is, however, critical for understanding host-pathogen interactions and may provide opportunities for the development of new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of septic inflammatory response (21).

We have employed a wide range of well defined synthetic PGN derivatives combined with surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements to establish whether human TLR2 can detect PGN. The binding data have been validated by cellular activation studies using highly purified and chemically modified PGN. It has been found that PGN derived from Gram-positive and -negative bacteria can be detected by TLR2. In the case of Gram-positive bacteria, the initial linear biosynthetic product and cross-linked PGN are poorly recognized, and active fragments are only formed after remodeling of PGN by bacterial autolysins. A wider range of PGN fragments derived from Gram-negative bacteria could be complexed with high affinity, including the nascent muramyl pentapeptide. The structure-activity relationship also demonstrates that modifying the structure of PGN can be a strategy used by bacteria to evade immune detection by TLR2. Cellular activation studies employing highly purified and chemically modified PGN support the established structure binding relationship.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents—Preparation of compound 2c was as follows. Sieber Amide resin (100 mg, 42 μmol was swelled in dimethylformamide (5 ml) for 45 min and then treated with piperidine in DMF (20%, 3 × 3 ml). After a reaction time of 30 min, the solvents were removed by filtration, and the resin was washed with DMF (3 × 3 ml) and then treated with Fmoc-d-alanine (26.1 mg, 84 μmol) in DMF in the presence of HATU (O-(7-aza-benzotriazole-1-yl)-N′,N′,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate) 31.9 mg, 84 μmol) and DIPEA N,N′-diisopropylethylamine (29 μl). The progress of the reaction was monitored by the Kaiser test. After completion of the coupling, the resin was washed with DMF (3 × 3 ml), and the Fmoc protection group was removed by treatment with piperidine in DMF (20%, 3 × 2 ml, 3 × 10 min). The reaction cycle was repeated using Fmoc-l-Lys(t-butoxycarbonyl)-OH (39.3 mg, 84 μmol), Fmoc-d-iso-Glu(Gly-benzyloxycarbonyl) (43.4 mg, 84 μmol), Fmoc-l-alanine (26.1 mg, 84 μmol), and 2-N-acetyl-1-β-O-allyl-4,6-benzylidine-3-muramic acid (38.1 mg, 84 μmol). The resulting resin-bound glycopeptide was washed with DMF (3 × 5 ml), dichloromethane (7 × 3 ml), and methanol (3 × 3 ml), dried in vacuo (10 h), re-welled in dichloromethane (5 ml), and filtered. The glycopeptide was released from the resin by treatment with trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane (2%, 10 × 2 ml). The resin washing were combined and concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue coevaporated with toluene. The crude product was subjected to trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane (20%, 3 ml) to ensure complete removal of the benzylidene- and t-butoxycarbonyl-protecting groups. Palladium in activated carbon (10%, 35 mg) was added to a solution of the crude compound in a mixture EtOH, H2O, 1 n HCl (4:2:0.02, v/v/v, 1.5 ml), and the reaction mixture was stirred for 40 h, after which it was passed through an Acrodisc syringe filter (0.2-μm supor membrane, PALL Life Sciences), and the resulting filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The benzyl ester of the resulting compound was removed by stirring under an atmosphere of H2 (1 atm) in presence of palladium in activated carbon (20 mg) in mixture of EtOH/H2O/HOAc (4:2:0.2, v/v/v, 1.6 ml) for 20 h. After completion of the reaction, palladium in activated carbon was filtered off through Acrodisc syringe filters (0.2 μm supor membrane), and the solvents were evaporated in vacuo. After purification by LH-20 size exclusion column chromatography using MeOH/dichloromethane as the eluent (1/1, v/v), the glycopeptide was further purified by semi-preparative high performance liquid chromatography (Eclipse XDB-C18 column, 5 μm, 9.4 × 250 mm; eluent: water, acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) to afford, after lyophilization of the appropriate fraction, the target compound 2c as a mixture of α/β anomers (8.1 mg, 64%). [α]22D =+52.23. 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ 5.11 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 1H; H-1), 4.21–4.44 (m, 5H; α-CH, Lys, α-CH, Glu, α-CH, Ala, α-CH, Lac), 3.33–3.91 (m, 6H; H-2, H-3, H-4, H-5, H-6ab), 3.00 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.86 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H; εCH2, Lys), 2.20–2.41 (m, 2H, γCH2, Glu), 1.98–218 m, 2H, βCH2, Glu), 1.78–1.88 (m, 4H, NHCH3, CH, Lys), 1.58–1.72 (m, 3H, 3 × CH, Lys), 1.22–1.42 ppm (m, 9H, CH3, Lac, 2 × CH3, 2 Ala); 13C (heteronuclear single quantum correlation): δ 89.23 (αC-1), 87.65 (βC-1), 84.28, 82.67, 79.67, 78.96, 74.43 (αC, Ala, Glu, Lys, Lac), 80.23, 76.65, 69.78, 69.31, 63.52, 62.32, 60.54, 55.76, 54.38, 53.62, 50.83, 46.87, 40.37 (εC, Lys), 32.65 (γC-Glu), 31.20, 28.21, 27.42 (βC-Glu), 26.31, 24.82, 23.76, 22.37, 22.22, 18.79, 17.65, 16.75 ppm; HRMS-MALDI-TOF calculated for C30H52N8O14 [M+Na]: 771.36; experimental: 771.35.

Compound 3b was prepared by a similar approach; however, instead of Fmoc-d-iso-Glu(Gly-benzyloxycarbonyl), Fmoc-d-isoglutamine, was employed as the third amino acid, and the first coupling amino acid was Fmoc-glycine. Each amino acid component was used in 2-fold excess with respect to loading of the resin. The target compound was obtained as a mixture of α/β anomers (10.6 mg, 71%). [α]22D =+23.12. 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ 5.02 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 0.70H; H-1-α anomer), 4.56 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 0.30H; H-1-β anomer), 4.20–4.34 (m, 4H; α-CH, Lys, α-CH, Glu, α-CH, Ala, α-CH, Lac), 3.31–4.00 (m, 8H; H-2, H-3, H-4, H-5, H-6ab, 2H, Gly), 2.88 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H, εCH2, Lys), 2.21–2.34 (m, 2H, γCH2, Glu), 1.78–1.97 (m, 4H, NHCH3, CH, Lys), 1.51–1.76 (m, 8H,), 1.23–1.42 ppm (m, 6H, CH3, Lac, CH3, Ala); HRMS-MALDI-TOF calculated for C30H53N9O13 [M+Na]: 770.37; experimental: 770.35.

Compound 6b was prepared by a similar approach; however, instead of Fmoc-l-Lys-OH, Fmoc-DAP(δ-CONH2)-OH was used as the third amino acid and Fmoc-d-Glu-benzyloxycarbonyl as the second amino acid. Each amino acid component was used in a 2-fold excess with respect to the loading resin. The target compound was obtained as a mixture of α/β anomers (2.1 mg, 42%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ 5.22 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 0.64H; H-1-α anomer), 4.71 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 0.36H; H-1-β anomer), 4.20–4.48 (m, 6H, α,ε-CH, DAP, α-CH, Glu, α-CH, Ala, α-CH, Lac), 3.70–4.00 (m, 4H; H-2, H-3, H-6a,b), 3.50–3.66 (m, 2H, H-4, H-5), 3.20 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.88–3.10 (m, 2H, γ-CH2, Glu), 2.44 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 2.09–2.40 (m, 5H, β-CH2, Glu, NHCOCH3), 1.38–1.61 (m, 9H, CH3, Lac, 2 x CH3, 2 Ala); HRMS-MALDI-TOF calculated for C29H50N8O14Na [M+Na]: 757.34; experimental: 757.31.

Compound 6c was prepared by a similar approach; however, instead of Fmoc-l-Lys-OH, Fmoc-DAP(δ-CONH2)-OH was used as the third amino acid. Fmoc-DAP(δ-CONH2)-OH was prepared by a cross-metathesis reaction of suitably protected vinyl glycine and allyl glycine followed by reduction of the double bond of the resulting compound. Each amino acid component was used in 2-fold excess with respect to loading of the resin. The target compound was obtained as a mixture of α/β anomers (6.2 mg, 62%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ 5.01 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 0.60H; H-1-α anomer), 4.55 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 0.40H; H-1-β anomer), 4.02–4.46 (m, 6H; α,ε-CH, DAP, α-CH, Glu, α-CH, Ala, α-CH, Lac), 3.31–3.92 (m, 6H, H-2, H-3, H-4, H-5, H-6a,b), 2.75–2.81 (m, 2H, γ-CH2, Glu), 2.22–2.36 (m, 5H, β-CH2, Glu, NHCOCH3), 1.97–2.09 (m, 2H, CH2, DAP), 1.24–1.38 ppm (m, 9H, CH3, Lac, 2 x CH3, 2 Ala); HRMS-MALDI-TOF calculated for C29H51N9O13Na [M+Na]: 756.77; experimental: 756.65.

Compounds 1, 2a, b, 3a, 4, 5, 6a, d, and 7 were prepared as described previously (22–27). Bacillus subtilis, Micrococcus luteus, and Staphylococcus aureus PGN were obtained from Fluka, Bacillus licheniformis, Escherichia coli, and Lactobacillus plantarum bacteria were from ATCC, E. coli 055:B5 LPS was from List Biological Laboratories, polymyxin B was from Bedford Laboratories, Pam3CysSK4 was from Calbiochem, poly(I)·poly(C) was from Amersham Biosciences, recombinant human tumor necrosis factor γ (TNF-α) was from Endogen, rat polyclonal antibody to human TLR2 (pAb hTLR2) was from InvivoGen, rat polyclonal IgG was from Sigma-Aldrich, and mouse monoclonal anti-polyhistidine antibody was from Qiagen. The sTLR2 plasmid (28) was a kind gift from Y. Kuroki (Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine).

Isolation and Purification of Insoluble PGN—B. licheniformis, E. coli, and L. plantarum were cultivated in Nutrient Broth (Difco), LB broth (Sigma), and Lactobacilli MRS Broth (Difco), respectively. Freshly prepared media were inoculated with the bacteria and incubated at 37 °C under aerobic conditions for 12–18 h. Insoluble B. licheniformis and L. plantarum PGN were isolated from the bacterial cells by treatment with SDS and glass beads and further treatment with α-amylase, DNase, and RNase. The isolated insoluble B. licheniformis and L. plantarum PGN and commercial B. subtilis, M. luteus, and S. aureus PGN were further purified by treatment with trypsin or Pronase, SDS, and HF as reported previously (19). Insoluble E. coli PGN was isolated from the bacterial cells by treatment with SDS and further treatment with α-amylase, Pronase, and SDS (29, 30).

N-Acetylation of PGN—The purified PGN of M. luteus and S. aureus (150 μg) was suspended in a cooled (4 °C) mixture of aqueous saturated NaHCO3 (100 μl) and Ac2O(1 μl, 10 μmol). After agitation for 18 h at 4 °C, the reaction mixture was centrifuged (13,000 rpm, 30 min), and the solvents were removed by decanting. The resulting pellet was washed five times by resuspension in deionized water (100 μl) followed by centrifugation and decanting. A Kaiser test showed the absence of free amine groups.

Expression and Purification of a Soluble Form of Recombinant Extracellular Human TLR2 Domain (sTLR2)—The recombinant soluble form of human TLR2 consisting of the putative extracellular domain (Met1–Arg587) and a His6 tag at the C-terminal end was expressed in a baculovirus-insect cell expression system. Monolayers of Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells (Invitrogen) were co-transfected with linearized baculovirus DNA (BaculoGold; BD Biosciences) and the pVL1393 plasmid vector (Invitrogen) containing cDNA for sTLR2 (28). Recombinant plaques were isolated, and viral titers were amplified to ∼1–10 × 107 plaque-forming units/ml. The recombinant viruses were used to infect monolayers of Trichoplusia ni (High Five) cells (Invitrogen) in serum-free medium at a multiplicity of 2–5. After a 3-day incubation, the medium was collected after low speed centrifugation. sTLR2 was purified by nickel nitrilotriacetic acid (Qiagen) chromatography according to the manufacturer's instructions using 300 mm imidazole to elute the sTLR2 from the resin. The sTLR2-containing fractions were concentrated using Nanosep centrifugal devices (Pall Life Sciences). The purified protein was dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (0.01 m; pH 7.4) and stored at -80 °C. The sTLR2 protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce). The purity of the protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) under reducing conditions with Coomassie G-250 (GelCode Blue Stain Reagent; Pierce) and silver (GelCode SilverSNAP Stain Kit II; Pierce) staining. The identity of the protein was confirmed by Western blotting using a rat polyclonal antibody to human TLR2 (pAb hTLR2) and an anti-histidine (penta-His horseradish peroxidase) antibody. Approximately 20 μg of sTLR2 was obtained from 1 ml of culture medium.

SPR Studies—Binding interactions between sTLR2 and various analytes were examined using a Biacore T100 biosensor system (Biacore Inc.-GE Healthcare). sTLR2 was immobilized by standard amine coupling using an amine coupling kit (Biacore Inc.-GE Healthcare). The surface was activated using freshly mixed N-hydroxysuccimide (100 mm) and 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-ethylcarbodiimide (391 mm) (1/1, v/v) in water. Next, sTLR2 (50 μg/ml) in aqueous NaOAc (10 mm, pH 4.5) was passed over the chip surface until a ligand density of ∼5000 resonance units (RUs) was achieved. The remaining active esters were quenched by aqueous ethanolamine (1.0 m; pH 8.5). The control flow cell was activated with hydroxysuccimide and ethylcarbodiimide followed by immediate quenching with ethanolamine. HBS-EP (0.01 m HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, 3 mm EDTA, 0.005% polysorbate 20, pH 7.4) was used as the running buffer for the immobilization and kinetic studies. Analytes were dissolved in running buffer, and a flow rate of 20 μl/min was employed for association and dissociation at a constant temperature of 25 °C. A double sequential 60 s injection of aqueous NaOH (50 mm; pH 11.0) at a flow rate of 50 μl/min followed by a 3-min stabilization with running buffer was used for regeneration and achieved prior base-line status. The same experimental surface was used for ∼2 weeks and maintained under running buffer conditions. MTP-DAP (amide/acid) (5) was used as a positive control in each experiment to check the stability of the TLR2 surface activity during the course of the experiments. Using Biacore T100 evaluation software (Biacore Inc.-GE Healthcare), the response curves of various analyte concentrations were globally fitted to either the 1:1 Langmuir model or the two-state binding model described by the following equation (31, 32),

|

(Eq. 1) |

where the equilibrium constant of each binding step is K1 = ka1/kd1, and K2 = ka2/kd2. The overall equilibrium constant is calculated as KA = K1(1 + K2) and KD = 1/KA. In this model, the analyte (A) binds to the ligand (B) to form an initial complex (AB), which undergoes a conformational change to form a more stable complex (AB*).

Biotinylation of sTLR2 and Immobilization of Biotinylated sTLR2—sTLR2 (40 μg/ml) was mixed with EZ-link™ TFP-PEO-biotin (Pierce) in phosphate-buffered saline (1:2 eq) and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Unreacted EZ-link™ TFP-PEO-biotin was removed by filtration of the mixture over a Nanosep centrifugal device with cut-off of 3 KDa (Pall Life Sciences). The biotinylated sTLR2 was resuspended in HBS-EP and immobilized by passing over a streptavidin-coated chip (Series S Sensor Chip SA (certified); Biacore) until a ligand density of ∼2000 RU was achieved. Next, a mixture of ethanolamine and biotin (10:1 eq) was passed over the ligand and control flow cells to block free streptavidin binding sites.

TNF-α ELISA—Differentiated Mono Mac 6 (MM6) cells were incubated with stimuli for 5.5 h in the presence of polymyxin B (PMB), and concentrations of TNF-α in culture supernatants were determined by a solid phase sandwich ELISA. PGN concentration-response data were analyzed using nonlinear least-squares curve fitting in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For details, see supplemental “Experimental Procedures.”

Transfection and NF-κB Activation Assay—HEK 293T wild type cells and HEK 293T cells stably transfected with human TLR2 or human TLR4/MD2/CD14 were transiently transfected using PolyFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen) with expression plasmids pELAM-Luc (NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter plasmid) (33) and pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase control reporter vector; Promega) as an internal control to normalize experimental variations. Forty-four hours post-transfection cells were exposed to the stimuli in the presence of fetal bovine serum for 4 h. The luciferase activity was measured in cell extracts using the Dual-luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). For details, see supplemental “Experimental Procedures.”

Other Methods—See supplemental “Experimental Procedures” for PGN composition analysis by high performance anion exchange chromatography and integrated pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC IPAD) and maintenance of cell lines.

Statistical Analysis—Multiple comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni' s multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

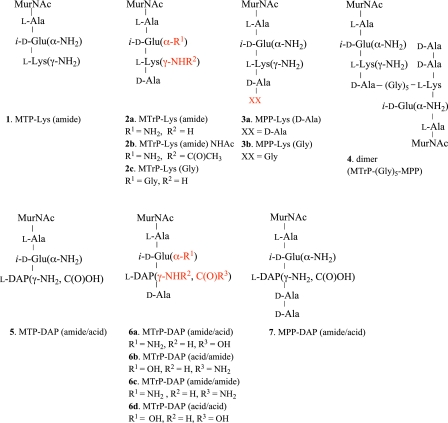

Analysis of the Binding of Human Soluble TLR2 to Synthetic PGN Part Structures—SPR has been employed to study the interactions of the soluble extracellular domain of human TLR2 with synthetic lysine- and DAP-containing PGN fragments 1–7 (Fig. 2). The lysine-containing muramyl tripeptide 1 (MTP-Lys), muramyl tetrapeptides 2a–c (MTrP-Lys), muramyl pentapeptides 3a,b (MPP-Lys), and dimer 4 are derived from PGN of Gram-positive bacteria. On the other hand, compounds 5–7 are part structures of Gram-negative and rod-shaped Gram-positive PGN and structurally similar to muropeptides 1–3, with the exception that the lysine residue is replaced by a DAP moiety. SPR studies using these derivatives have established the importance of each amino acid of the stem peptide for binding and uncovered that TLR2 can recognize PGN derived from Gram-positive and -negative bacteria. Furthermore, muramyl pentapeptides 3a and 7 are derived from nascent PGN, whereas the muramyl tri-(1, 5) and tetrapeptides (2, 6) represent structures that can be formed during PGN remodeling by bacterial autolysins. The use of these compounds has uncovered the importance of nascent and remodeled PGN for TLR2 recognition.

FIGURE 2.

Structures of synthetic muropeptides. Lysine-containing compounds 1–4 derived from PGN of Gram-positive bacteria and DAP-containing compounds 5–7 derived from Gram-negative and rod-shaped Gram-positive PGN.

Cross-linking of Gram-positive PGN results in the loss of a terminal d-Ala moiety to generate a tetrapeptide, which is linked to an ε-amino group of the lysine of another PGN polymer through a glycine-containing interpeptide bridge (Fig. 1A). Compound 4, which is composed of a muramyl tetrapeptide linked through a pentaglycine bridge peptide to a muramyl pentapeptide, was employed to study the influence of PGN cross-linking on TLR2 recognition. Bacterial endopeptidases can cleave the glycine interpeptide bridge to generate a stem tetrapeptide extended by glycine moieties (Fig. 1A). Muramyl pentapeptide 3b represents such a structure and contains a tetrapeptide extended by one Gly moiety. Derivative 2b was used to establish the influence of acylation of the lysine side chain amino group (R2) for binding. This modification was deemed important because it mimics the attachment of this functionality to the penultimate d-Ala of another PGN chain as in S. aureus PGN.

Many bacterial strains modify the α-carboxylic acid of isoglutamic acid of PGN by amidation or by the addition of Gly (6, 7). The importance of the chemical nature of the α-carboxylic acid of iso-d-Glu (R1) of lysine containing PGN was investigated by employing compound 2c, which has a glycine linked to iso-d-Glu as in M. luteus PGN. Bacteria that biosynthesize DAP-containing PGN can have the α-carboxylic acid of iso-d-Glu (R1) and the γ-carboxylic acid of DAP (R3) as an amide or acid. The importance of these modifications was investigated using muramyl tetrapeptides 6a–d, which are derived from B. licheniformis (6a), B. subtilis (6b), L. plantarum (6c), and E. coli (6d) and have the carboxylic acids in the amide or acid form.

A baculovirus insect cell expression system was used to obtain recombinant human sTLR2 (28). The protein was modified by a His6 tag, which facilitated purification by nickel nitrilotriacetic acid column chromatography. SDS-PAGE analysis and Western blotting confirmed the homogeneity of the protein (supplemental Fig. S1).

SPR is a rapid and sensitive method for the evaluation of affinities of biomolecular interactions (34) that has as a benefit that it relies exclusively on mass changes, thus allowing the study of interactions in real time without the need for external labels such as fluorophores, which in some cases can alter the nature of the interaction. Collecting SPR data for low molecular weight analytes such as compounds 1–7 is challenging because the refractive index monitored during a binding event is relatively small and, thus, results in responses with much lower magnitudes than those observed in typical protein-protein interactions. Despite these challenges, the high sensitivity and reproducibility of modern instruments combined with proper experimental design permits the direct monitoring of the binding of low molecular weight analytes to immobilized proteins (35).

Approximately 5000 RU of sTLR2 were immobilized on hydroxysuccimide-activated groups of a CM-5 research grade sensor chip surface, and titration experiments were performed with the synthetic compounds. Good agreements between the theoretically predicted and experimentally observed maximal specific binding (Rmax) parameters indicated that amine immobilization of the protein yielded fully active surfaces. The high mass transport coefficients (>1010) obtained from the kinetic model fit with mass transport limitation (MTL) experiments using the MTL wizard were indicative of insignificant mass transport effects and negligible rebinding of the analyte during the post-injection phase (data not shown). For all SPR experiments, bulk refraction caused by the difference in the refractive index of the running buffer and sample injection was negated by using a control cell functionalized by ethanolamine.

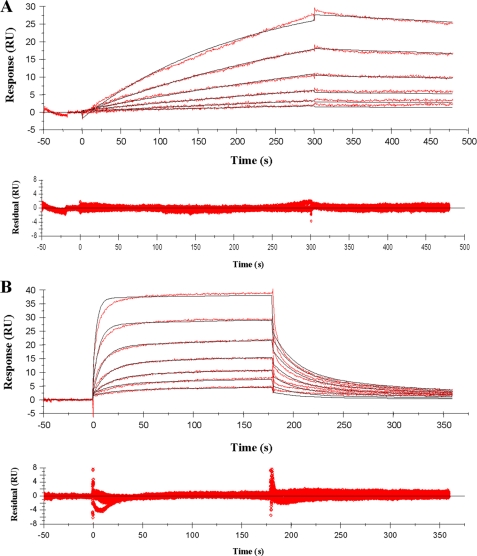

Representative sensorgrams for the interaction of lysine-containing muramyl tripeptide 1 with immobilized sTLR2 are shown in Fig. 3A. A 1:1 Langmuir binding model gave an excellent fit of the sensorgrams (χ2 = 0.26) and provided a KD of 78 μm (Table 1). Furthermore, a slow association and dissociation characterized the binding. Some heterogeneity was observed at the highest concentration of analyte tested, and therefore, TLR2 was immobilized by an alternative method at a lower loading (2000 RU) by biotinylation of TLR2 using EZ-link™ TFP-PEO-biotin and a streptavidin-coated chip. Binding experiments gave very similar sensorgrams (supplemental Fig. S3), and kinetic analysis provided a dissociation constant of 97 μm, underscoring that heterogeneity at the highest concentrations of analyte does not significantly affect the binding affinity.

FIGURE 3.

Sensorgrams representing the concentration-dependent kinetic analysis of lysine- and DAP-containing PGN part structures with immobilized sTLR2 (5000 RU). Shown are simultaneous kinetic analysis of 2-fold serial dilutions of MTP-Lys (amide) 1 at concentrations of 500 to 15.6 μm, fitted with a Langmuir 1:1 binding model (black lines) (A) and MTP-DAP (amide/acid) 5 at concentrations of 100 to 1.6 μm, fitted with a two-state binding model (black lines) (B). The corresponding residual values are plotted below the individual sensorgrams. Triplicate measurements provided KD values of 78 ± 6, and 11 ± 2 μm for 1 and 5, respectively. As negative controls, E. coli LPS and poly(I)·poly(C), which are agonists of TLR4 and TLR3, respectively, were used and gave no binding (supplemental Fig. S2). The TLR2 agonist Pam3CysSK4 was employed as a positive control, which showed binding in a dose-dependent manner but an affinity constant could not be determined due to a poor fit of the sensorgrams, probably as a result of aggregation of the analyte.

TABLE 1.

Binding affinity constants (KD) for the interaction of TLR2 with synthetic compounds 1–7 The recombinant extracellular domain of human sTLR2 was immobilized on NHS-activated groups of a CM-5 sensor chip surface (5000 RU), and titration experiments were performed with the synthetic compounds 1–7. The binding constants of compounds 1, 2a,b, 3b, and 6b were determined by fitting the data using a 1:1 binding model. For compounds 5, 6a, 6c, and 7, a two-state binding model was employed to determine binding constants. The kinetic binding parameters are provided in supplemental Table S2. NB indicates no binding at 100 μm. Sensorgrams representing the kinetic analysis are presented in Fig. 3 for compounds 1 and 5 and in supplemental Fig. S2 for compounds 2a–c, 3a,b, 4, 6a–d, and 7. Data represent mean values ± S.D. (n = 3). A statistical significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed between 1 versus 2a, 2a versus 2b, 6a versus 6c, and 6b versus 6c.

| Analyte | KD |

|---|---|

| μm | |

| MTP-Lys (amide) 1 | 78 ± 6 |

| MTrP-Lys (amide) 2a | 18 ± 0 |

| MTrP-Lys (amide) NHAc 2b | 241 ± 64 |

| MTrP-Lys (Gly) 2c | >1000 |

| MPP-Lys (d-Ala) 3a | >1000 |

| MPP-Lys (Gly) 3b | 258 ± 96 |

| MTrP-(Gly)5-MPP 4 | >1000 |

| MTP-DAP (amide) 5 | 11 ± 2 |

| MTrP-DAP (amide/acid) 6a | 12 ± 1 |

| MTrP-DAP (acid/amide) 6b | 3.6 ± 2.0 |

| MTrP-DAP (amide/amide) 6c | 56 ± 12 |

| MTrP-DAP (acid/acid) 6d | NB |

| MPP-DAP (amide) 7 | 10 ± 1 |

Muramyl tetrapeptide 2a exhibited a similar kinetic profile than 1; however, in this case a slightly smaller KD was determined, indicating that the d-Ala moiety attached to isoglutamate contributes somewhat to binding. Muramyl pentapeptide 3a showed binding only at very high concentrations (>500 μm), which made it difficult to accurately determine a binding constant and established that TLR2 cannot accommodate the second d-Ala moiety of 3a. Dimer 4 was also poorly recognized by TLR2; however, muramyl pentapeptide 3b, which contains one glycine moiety linked to the stem peptide, was recognized with modest affinity. These results indicate that nascent PGN (muramyl pentapeptide) and the initial cross-linked product are poorly recognized by TLR2. However, PGN remodeling products such as compounds 1, 2a, and 3b are recognized by the receptor.

Muramyl tetrapeptide 2b, which has a lysine with an acetylated side chain, was found to bind with a 10-fold reduced affinity compared with amine-containing muropeptide 2a, further demonstrating that cross-link leads to loss of activity. Compound 2c, which contains an isoglutamic acid moiety extended by glycine, was poorly recognized by TLR2, indicating that modification of the α-carboxylic acid of isoglutamine is a strategy by microbes to avoid innate immune detection by TLR2.

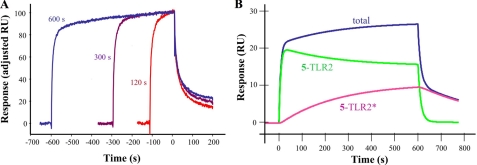

Surprisingly, the titration sensorgrams of the DAP-containing compound 5 showed a very distinct binding profile in which an initial fast association was followed by slow increase in binding (Fig. 3B). A 1:1 binding model gave an unsatisfactory fit because of nonrandom distribution of residuals during the dissociation phase (supplemental Fig. S4). A two-state binding model provided, however, a good fit (χ2 = 0.57), and a KD of 11 μm was established. A contact time experiment, in which the dissociation phase of binding sensorgrams is analyzed as a function of time, was performed to confirm the two-state binding model (Fig. 4A) (31, 32). As expected, the dissociation rate became progressively slower after a longer injection (contact) time (120, 300, and 600 s gave 6.2 × 10-3, 4.5 × 10-3, and 3.1 × 10-3 s-1, respectively), which is in agreement with a two-state binding model. Furthermore, simulation of the rate constants of the experimentally determined response curve for a 600-s contact time experiment using the two-state binding model equation showed that fast complexation between TLR2 and compound 5 (5-TLR2) is followed by a slow conformational change to give 5-TLR2* (Fig. 4B). The initial complex (5-TLR2) dissociates fast, whereas the complex that has undergone a conformational change (5-TLR2*) has a delayed release of bound compound and is more stable. A two-state binding model can also be rationalized by a sequential two-step binding process; however, the small size of the ligand makes such a process unlikely. Finally, the association constant established by kinetic analysis was validated by an experiment that employed an extended contact time of 15 min to achieve a state close to equilibrium. The latter feature made it possible to analyze the data using a steady state equilibrium model, which provided a KD of 21 μm, a value that is in close agreement with that obtained by kinetic analysis.

FIGURE 4.

A contact time experiment using TLR2 and compound 5 to confirm a two-state binding model. Adjusted binding curves for the MTP-DAP (amide/acid) (5;50 μm) for exposure times of 120 s (red), 300 s (purple), and 600 s (blue) are shown (A). The analyte injection end point of each time point was set to the same value on the y axis (100) and x axis (0) to indicate the point at which the comparison of the various dissociation phases began. The dissociation rates of triplicate measurements were 6.2 ± 0.6 × 10-3, 4.5 ± 1.1 × 10-3, and 3.1 ± 0.1 × 10-3 s-1 at analyte exposure times of 120, 300, and 600 s, respectively. A statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed between 120 versus 600 s. The total binding (blue) represents the observed data for a 600 s exposure using 5 at 50 μm (B). The formation of the initial complex 5-TLR2 (green) and the complex, which has undergone a conformational change (5-TLR2*; pink), are obtained by simulating the equation for two-state binding (see “Experimental Procedures”).

Muramyl tetrapeptide 6a and muramyl pentapeptide 7 bound with similar affinities as 5, indicating that in the case of DAP-containing muropeptides, the TLR2 protein can accommodate the d-Ala-d-Ala moiety but does not contribute to binding. In these cases, the sensorgrams could only be properly fitted using a two-state binding model. Finally, it was observed that the chemical nature of the α-carboxylic acid of iso-Glu(n) and the γ-carboxylic acid of DAP can have a dramatic impact on binding. Thus, compounds 6b and 6c bound in the low- and mid-micromolar range, respectively, whereas binding was abolished when compound 6d was employed.

Cellular Activation Studies with Purified and Chemically Modified PGN—A number of cellular activation studies were performed to validate the biological significance of the in vitro binding studies. First, cellular responses induced by highly purified S. aureus PGN were compared with those of a PGN preparation, in which free amino functionalities were acetylated with acetic anhydride. It was expected that acetylation of the free amines would lead to a reduction of biological activity because the SPR studies had shown that this functionality of lysine contributes significantly to binding (compound 2a versus 2b). Furthermore, the activity of M. luteus PGN was investigated because this Gram-positive bacterium modifies the α-carboxylic acid of isoglutamine with glycine, and our binding studies have shown that such a modification dramatically reduces the affinity for TLR2 (compound 2a versus 2c). Thus, it was expected that PGN from M. luteus would display low biological activity. In addition, PGN from B. licheniformis, B. subtilis, L. plantarum, and E. coli were studied because these bacterial strains express DAP-containing PGN that differ in chemical nature of the α- and γ-carboxylic acid of iso-Gln and DAP. The SPR studies had established that these modifications can have a dramatic impact on binding to TLR2 (compounds 6a–d).

The various PGNs were purified by treatment with Pronase or trypsin to remove proteins and lipoproteins followed by washing with SDS to remove noncovalently bound lypophilic residues and, finally, exposure to HF (48% v/v) to cleave phosphodiesters of teichoic acids (19). The structural identity of the PGNs was determined by acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of the amide and glycosidic linkages followed by amino acid and monosaccharide analysis using HPAEC IPAD (supplemental Fig. S5). The free amino groups of lysine-containing PGNs from S. aureus and M. luteus PGN were acetylated by reaction with acetic anhydride in aqueous saturated sodium bicarbonate. The absence of any free amino groups was confirmed by the Kaiser test.

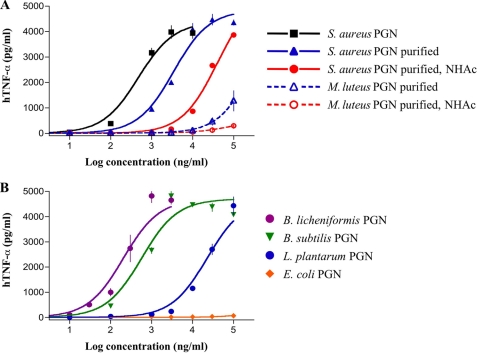

Next, a human monocytic cell line (MM6) was exposed over a wide range of concentrations to the various PGN preparations. After 5.5 h, the supernatants were harvested and examined for TNF-α using capture ELISA. Potencies (EC50, concentration producing 50% activity) and efficacies (maximal level of production) were determined by fitting the dose-response curves to a logistic equation using PRISM software. Interestingly, each S. aureus PGN preparation yielded clear dose-response curves (Fig. 5A). The purification protocol led, however, to a significantly lower potency demonstrating that PGN contains contaminants that induce TNF-α production. S. aureus PGN in which the free amines were acetylated gave an EC50 that was ∼10-times larger compared with unmodified PGN, which is in agreement with the finding that acetylation of ε-amine of the lysine moiety of (2a versus 2b) resulted in a significantly reduction in binding affinity (Table 1). Importantly, purified PGN from M. luteus induced TNF-α only at very high concentrations, and the estimated EC50 value is at least 2 orders of magnitude larger than that of S. aureus. This observation is in agreement with the results of the binding studies, which have shown that glycine modification of isoglutamine of PGN, as observed in M. luteus, leads to a significant reduction in binding. As expected, acetylation of PGN of M. luteus abolished activity.

FIGURE 5.

Induction of TNF-α production by MM6 cells treated with different PGNs. TNF-α production after treatment with lysine-containing PGNs (A). MM6 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of unpurified and purified S. aureus PGN before and after N-acetylation and purified M. luteus PGN before and after N-acetylation for 5.5 h. TNF-α protein in cell supernatants was determined using ELISA. The best-fit EC50 values are 0.5, 3.4, and 40.2 μg/ml for S. aureus PGN, purified S. aureus PGN, and purified/N-acetylated S. aureus PGN, respectively. An estimated EC50 value of 184 μg/ml was obtained for purified M. luteus PGN. All combinations of EC50 values gave statistical significant differences (p < 0.05). TNF-α production was measured after treatment with DAP-containing PGNs (B). MM6 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified B. licheniformis, B. subtilis, L. plantarum, and E. coli PGN for 5.5 h. The best-fit EC50 values and statistical analysis are reported in Table 2. Pronase-treated PGNs gave similar dose-response curves. Data represent the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3).

The biological activities of the DAP-containing PGNs modeled the findings of the binding studies. Thus, PGN obtained from B. licheniformis, B. subtilis, and L. plantarum, which contain iso-Glu and DAP moieties similar to compounds 6a, 6b, and 6c, respectively, induced the secretion of TNF-α (Fig. 5B and Table 2). L. plantarum PGN was less active than the two other preparations and contains a muropeptide (6c) that bound with lower affinity with TLR2. Importantly, E. coli PGN did not induce the secretion of TNF-α, which is in agreement with the finding that muropeptide 6d, which has iso-Glu and DAP moieties similar to E. coli PGN, did not bind with TLR2.

TABLE 2.

EC50 values of TNF-α production induced by DAP-containing PGNs MM6 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified B. licheniformis, B. subtilis, L. plantarum, and E. coli PGN for 5.5 h. TNF-α protein in cell supernatants was determined using ELISA. The dose-response curves are presented in Fig. 5B.

| PGN | ECM50a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| μg/ml | |||

| B. licheniformis | 0.21 | 0.12–0.36 | |

| B. subtilis | 0.57 | 0.28–1.18 | |

| L. plantarum | 23 | 16–33 | |

| E. coli | NAb | NA | |

Values of EC50 are reported as best-fit values and as 95% confidence intervals of the EC50. A statistical significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed between B. licheniformis versus L. plantarum PGN and B. subtilis versus L. plantarum PGN

NA indicates no activity at 100 μg/ml

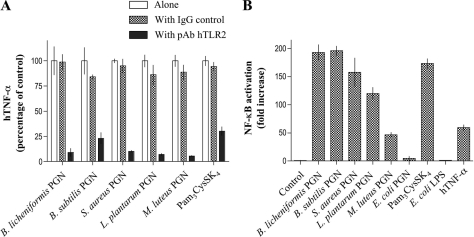

Next, the receptor specificity of the responses was investigated by pretreatment of MM6 cells with an anti-human TLR2 antibody followed by exposure to purified PGNs (Fig. 6A). Rat pAb hTLR2 was able to abolish TNF-α secretion, demonstrating that the PGN preparations mediate biological responses through TLR2. This conclusion was further validated by employing HEK 293T cells stably transfected with various immune receptors and transiently transfected with a plasmid containing the reporter gene pELAM-Luc (NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter vector) and a plasmid containing the control gene pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase control reporter vector). As can be seen in Fig. 6B, highly purified PGN could induce activation of NF-κB in a TLR2-dependent manner. No activation was observed in wild type HEK293T cells and cells transfected with human TLR4/MD2/CD14 (supplemental Fig. S6). Previously, it was observed that treatment of PGNs with trypsin resulted in a loss of NF-κB activation when exposed to HEK 293T cells expressing TLR2 (19). The discrepancy with our results is most likely because of the fact that the previous study examined cellular activation only at a relatively low concentration of 1 μg/ml, at which PGN does not induce cellular activation.

FIGURE 6.

TLR2 dependence of cellular activation by PGN. Effect of anti-TLR2 pAb on activity of PGNs in MM6 cells (A). MM6 cells were preincubated with a rat anti-human TLR2 pAb (5 μg/ml), a nonspecific rat IgG control (5 μg/ml), or medium for 30 min at 4 °C. TNF-α was measured after 5.5 h of stimulation with different PGNs or Pam3CysSK4 at their IC50 concentration (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Results are expressed as percentage of TNF-α concentration of control cells, which are incubated only with the various stimuli. In each case, no significant difference was observed between exposure to PGN or Pam3CysSK4 alone and in the presence of rat IgG control. Response of HEK293T cells expressing human TLR2 to different PGNs (B). Induction of NF-κB activation was determined in cultures of HEK293T cells stably transfected with human TLR2 and transiently transfected with pELAM-Luc and pRL-TK plasmids. Forty-four hour post-transfection, cells were treated with purified PGNs (100 μg/ml each) or were left untreated (control). Forty-eight hours post-transfection, NF-κB activation, as firefly luciferase activity relative to Renilla luciferase activity, was determined. As positive controls, Pam3CysSK4 (1 μg/ml) and human TNF-α (hTNF-γ, 10 ng/ml) were used, and as a negative control, E. coli LPS (1 ng/ml) was used. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, NF-κB activation was determined. -Fold change is -fold increase over control (cells exposed to medium only is arbitrarily set at 1). Data represent the mean values ± S.D. (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Bacterial growth and division involves the remodeling of the very strong PGN layer by bacterial autolysins such as N-acetyl muramidases, N-acetyl muramoyl-l-alanine amidases, and carboxypeptidases (9–11). During this process, soluble PGN fragments are lost to the bloodstream and a growing body of literature indicates that these turnover products can initiate innate immune responses (12–17, 21, 36–38). The structural complexity of PGN and covalent modification with inflammatory mediators such as lipoproteins and teichoic acids has made it difficult to firmly establish TLR2 as an innate immune receptor of PGN (19, 20).

Previously, it was observed that purification of PGN by Pronase or trypsin followed by treatment with SDS and exposure to HF led to loss of TLR2-mediated activity. This study did, however, not consider that cross-linked PGN isolated from bacterial cell walls may be of low activity. Furthermore, it also did not account for the importance of modification of carboxylic acids of isoGlu and DAP for biological activity.

The data reported here demonstrate that TLR2 can bind PGN fragments derived from Gram-positive and -negative bacteria. In the case of lysine-containing PGN (derived from Gram-positive bacteria), the initial linear biosynthetic product that contains pentapeptides such as in compound 3a and cross-linked PGN (e.g. dimer 4) is poorly recognized by TLR2. However, fragments (1, 2a, and 3b), which can be formed by the remodeling of PGN by autolysins, complexed with moderate to high affinity. Gram-positive bacteria have a very thick lysine-containing PGN layer, which accounts for approximately half of the cell wall mass. Thus, TLR2 may have evolved in such a way that it only recognizes a limited number of lysine-containing PGN motifs to avoid over-activation of innate immune responses.

Interestingly, a wider range of DAP-containing fragments (derived from Gram-negative bacteria) was recognized by TLR2 including the nascent muramyl pentapeptide 7 and PGN remodeling products such as muramyl tri-(5) and tetrapeptide 6a. The relaxed recognition specificity is probably because of the fact that Gram-negative bacteria contain only a thin DAP-containing PGN layer in the periplasmic space and, therefore, are less likely to cause over-activation of the innate immune system.

The binding studies also reveal that modification of carboxylic acids of iso-Glu and DAP dramatically influences binding. The functional significance of this finding is that modification of the carboxylic acids may be a strategy used by bacteria to evade detection by TLR2. In this respect, the ability to evade host immune surveillance is a critical virulence determinant for any pathogenic microorganism. However, the host may have developed strategies to compensate for lack of recognition by TLR2, and for example, it appears that NOD proteins respond differently to modification of the carboxylic acids of iso-Glu and DAP (39).

The mechanism by which TLR2 discriminates between PGN of Gram-positive and -negative bacteria appears to be unique. In the case of the NOD proteins, two different receptors have evolved that either respond to DAP (NOD1)- or lysine (NOD2)-containing muropeptides (12–15). The four mammalian PGRPs (PGRP-L, PGRP-Iα, PGRP-Iβ, and PGRP-S) employ dual strategies for PGN recognition; that is, one based on lysine or DAP specificity and another that relies on sensing the PGN cross-bridge (25, 27, 40). In the case of TLR2, one receptor can recognize lysine as well as DAP-containing muropeptides, yet it responds differently to these two classes of compounds due to different binding modes of lysine- and DAP-containing muropeptides.

To validate the biological significance of the binding studies, PGN from various bacterial strains were isolated and purified and examined over a wide concentration range for the ability to induce TNF-α production in a TLR2-dependent manner. The PGNs were selected in such a way that they contained either lysine or DAP as the third amino acids and modified differently at iso-Glu and DAP. Importantly, PGNs that contain muropeptides that bind with low affinity with TLR2 exhibited a low or no potency for inducing the production of TNF-α. Furthermore, DAP containing PGNs from B. licheniformis and B. subtilis were significantly more potent than lysine-containing S. aureus PGN. Also, acetylation of the amino groups of S. aureus PGN, a modification that led to a reduced affinity of muropeptides for TLR2 (2a versus 2b), led to a reduction in potency of TNF-α production.

Collectively, the studies reported support the involvement of TLR2 is an innate immune sensing of polymeric PGN. A number of other reports support the notion that polymeric PGN possesses inflammatory properties. For example, in vitro and in vivo degradation of the glycan backbone of PGN by lysozyme abrogates arthrogenicity and cytokine formation in whole blood (41, 42) as well as PGN-induced organ failure in rats (43). The importance of PGN backbone integrity was also demonstrated in lysozyme-deficient mice, which are more susceptible to inflammation induced by PGN (44). The potency of cellular activation by NOD receptors is reduced when the saccharide backbone increases in length (45) and, hence, these proteins are probably not involved in inflammatory responses induced by polymeric PGN.

The potency of several PGNs to initiate inflammatory responses is lower than that of LPS and lipid A (46). Bacterial autolysins such as carboxypeptidases and endopeptidases (9–11), which are involved in PGN remodeling can, however, solubilize and unmask glycopeptide moieties that can bind with high affinity with TLR2. Soluble polymeric PGN fragments that contain these peptide moieties should be able to induce the clustering of TLR2 receptors (47) and initiate cellular activation. Hence, the functional significance of the binding data is that endotoxicity arises from these subcomponents rather than from naïve cell wall PGN.

It is to be expected that antagonists of TLR2 can prevent over-activation of innate immune responses and, therefore, play valuable roles in the treatment of Gram-positive and -negative sepsis. In this respect, potent antagonists of lipopolysaccharides, which induce inflammatory responses through TLR4, have already been developed, and clinical studies indicate that these compounds are useful for the prevention or treatment of Gram-negative sepsis (48).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Y. Kuroki (Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, Japan) for providing the sTLR2 plasmid vector and Dr. E. D. Roush (Biacore, Inc.-GE Healthcare) for assistance with the evaluation of SPR measurements.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM065248. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S6.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PAMP, pathogen-associated molecular pattern; PGN, peptidoglycan; TLR, Toll-like receptor; sTLR, soluble TLR; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PGRP, PGN recognition protein; NOD, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain; DAP, diaminopimelic acid; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; MTP, muramyl tripeptide; HPAEC IPAD, high performance anion exchange chromatography and integrated pulsed amperometric detection; MM6, Mono Mac 6; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide; pAb, polyclonal antibody; RU, resonance units; Fmoc, N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl; HRMS-MALDI-TOF, high resolution mass spectra-matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; Mur, muramyl.

References

- 1.Janeway, C. A., and Medzhitov, R. (2002) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20 197-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medzhitov, R., and Janeway, C. A. (2002) Science 296 298-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pittet, D., Tarara, D., and Wenzel, R. P. (1994) J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 271 1598-1601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice, T. W., and Bernard, G. R. (2005) Annu. Rev. Med. 56 225-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darveau, R. P. (1998) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1 36-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghuysen, J. M. (1968) Bacteriol. Rev. 32 425-464 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schleifer, K. H., and Kandler, O. (1972) Bacteriol. Rev. 36 407-477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tipper, D. J., Katz, W., Strominger, J. L., and Ghuysen, J. M. (1967) Biochemistry 6 921-929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strominger, J. L., and Ghuysen, J. M. (1967) Science 156 213-221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith, T. J., Blackman, S. A., and Foster, S. J. (2000) Microbiology 146 249-262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheffers, D. J., and Pinho, M. G. (2005) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69 585-607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamaillard, M., Girardin, S. E., Viala, J., and Philpott, D. J. (2003) Cell Microbiol. 5 581-592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dziarski, R. (2003) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60 1793-1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inohara, N., and Nunez, G. (2003) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3 371-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girardin, S. E., and Philpott, D. J. (2004) Eur. J. Immunol. 34 1777-1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dziarski, R. (2004) Mol. Immunol. 40 877-886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steiner, H. (2004) Immunol. Rev. 198 83-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshimura, A., Lien, E., Ingalls, R. R., Tuomanen, E., Dziarski, R., and Golenbock, D. (1999) J. Immunol. Lett. 163 1-5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Travassos, L. H., Girardin, S. E., Philpott, D. J., Blanot, D., Nahori, M. A., Werts, C., and Boneca, I. G. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5 1000-1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dziarski, R., and Gupta, D. (2005) Infect. Immun. 73 5212-5216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myhre, A. E., Aasen, A. O., Thiemermann, C., and Wang, J. E. (2006) Shock 25 227-235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chowdhury, A. R., Siriwardena, A., and Boons, G. J. (2002) Tetrahedron Lett. 43 7805-7807 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhury, A. R., and Boons, G. J. (2005) Tetrahedron Lett. 46 1675-1678 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roychowdhury, A., Wolfert, M. A., and Boons, G. J. (2005) Chembiochem 6 2088-2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar, S., Roychowdhury, A., Ember, B., Wang, Q., Guan, R., Mariuzza, R. A., and Boons, G. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 37005-37012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan, R., Roychowdhury, A., Ember, B., Kumar, S., Boons, G. J., and Mariuzza, R. A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 17168-17173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swaminathan, C. P., Brown, P. H., Roychowdhury, A., Wang, Q., Guan, R., Silverman, N., Goldman, W. E., Boons, G. J., and Mariuzza, R. A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 684-689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwaki, D., Mitsuzawa, H., Murakami, S., Sano, H., Konishi, M., Akino, T., and Kuroki, Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 24315-24320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glauner, B. (1988) Anal. Biochem. 172 451-464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Jonge, B. L. M., Chang, Y. S., Gage, D., and Tomasz, A. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267 11248-11254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlsson, R., and Falt, A. (1997) J. Immunol. Methods 200 121-133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipschultz, C. A., Li, Y., and Smith-Gill, S. (2000) Methods 20 310-318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chow, J. C., Young, D. W., Golenbock, D. T., Christ, W. J., and Gusovsky, F. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 10689-10692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonsson, U., Fagerstam, L., Ivarsson, B., Johnsson, B., Karlsson, R., Lundh, K., Lofas, S., Persson, B., Roos, H., Ronnberg, I., et al. (1991) Biotechniques 11 620-627 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas, C. J., Surolia, N., and Surolia, A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 29624-29627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doyle, R. J., and Dziarski, R. (2001) in Sussman, M. (ed). Molecular Medical Microbiology, pp. 137-154, Academic Press, Inc., London, England

- 37.Boneca, I. G. (2005) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8 46-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cloud-Hansen, K. A., Peterson, S. B., Stabb, E. V., Goldman, W. E., McFall-Ngai, M. J., and Handelsman, J. (2006) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4 710-716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfert, M. A., Roychowdhury, A., and Boons, G. J. (2007) Infect. Immun. 75 706-713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guan, R., and Mariuzza, R. A. (2007) Trends Microbiol. 15 127-134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janusz, M. J., Esser, R. E., and Schwab, J. H. (1986) Infect. Immun. 52 459-467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoijer, M. A., Melief, M. J., Debets, R., and Hazenberg, M. P. (1997) Eur. Cytokine Netw. 8 375-381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myhre, A. E., Stuestol, J. F., Dahle, M. K., Overland, G., Thiemermann, C., Foster, S. J., Lilleaasen, P., Aasen, A. O., and Wang, J. E. (2004) Infect. Immun. 72 1311-1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ganz, T., Gabayan, V., Liao, H. I., Liu, L., Oren, A., Graf, T., and Cole, A. M. (2003) Blood 101 2388-2392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inamura, S., Fujimoto, Y., Kawasaki, A., Shiokawa, Z., Woelk, E., Heine, H., Lindner, B., Inohara, N., Kusumoto, S., and Fukase, K. (2006) Org. Biomol. Chem. 4 232-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, Y., Gaekwad, J., Wolfert, M. A., and Boons, G. J. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129 5200-5216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozinsky, A., Underhill, D. M., Fontenot, J. D., Hajjar, A. M., Smith, K. D., Wilson, C. B., Schroeder, L., and Aderem, A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 13766-13771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawkins, L. D., Christ, W. J., and Rossignol, D. P. (2004) Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 4 1147-1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.