Abstract

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) is an intracellular messenger that elicits a wide range of spatial and temporal Ca2+ signals, and this signaling versatility is exploited to regulate diverse cellular responses. In this study, we have developed a series of IP3 biosensors that exhibit strong pH stability and varying affinities for IP3, as well as a method for the quantitative measurement of cytosolic concentrations of IP3 ([IP3]i) in single living cells. We applied this method to elucidate IP3 dynamics during agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations, and we demonstrated cell type-dependent differences in IP3 dynamics, a nonfluctuating rise in [IP3]i and repetitive IP3 spikes during Ca2+ oscillations in COS-7 cells and HSY-EA1 cells, respectively. The size of the IP3 spikes in HSY-EA1 cells varied from 10 to 100 nm, and the [IP3]i spike peak was preceded by a Ca2+ spike peak. These results suggest that repetitive IP3 spikes in HSY-EA1 cells are passive reflections of Ca2+ oscillations, and are unlikely to be essential for driving Ca2+ oscillations. In addition, the interspike periods of Ca2+ oscillations that occurred during the slow rise in [IP3]i were not shortened by the rise in [IP3]i, indicating that IP3-dependent and -independent mechanisms may regulate the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. The novel method described herein as well as the quantitative information obtained by using this method should provide a valuable and sound basis for future studies on the spatial and temporal regulations of IP3 and Ca2+.

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)2 is an important intracellular messenger produced by phospholipase C (PLC)-dependent hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). IP3 releases Ca2+ from intracellular stores via IP3 receptors (IP3Rs), and the resulting Ca2+ signals often exhibit complex spatial and temporal organizations, such as Ca2+ oscillations (1). The mechanism responsible for Ca2+ oscillations has been a long-standing question, and a number of experimental approaches and mathematical models have been reported to account for these Ca2+ signals, yet the mechanism responsible remains controversial (2). There are two general classes of Ca2+ oscillation models (3). In one class, Ca2+ oscillations are generated in the presence of constant cytosolic IP3 concentrations ([IP3]i) (4); in the other class, oscillating [IP3]i are required to drive Ca2+ oscillations (5). The physiological relevance of the former class has been supported experimentally by using nonmetabolizable IP3 analogs (6), and by the observation of repetitive Ca2+ release in permeabilized cells with clamped IP3 concentrations (7, 8). On the other hand, oscillatory changes in [IP3]i have been suggested by the observed cyclical translocation of a GFP-tagged pleckstrin homology domain of PLC-δ (GFP-PHD) (9, 10). However, in other experiments using more specific IP3 biosensors, IP3 was shown to accumulate gradually with little or no fluctuation during Ca2+ oscillations (11). These discrepant observations may be attributable to differences between various IP3 biosensors and a lack of quantitation.

There are two types of IP3 biosensors, GFP-PHD and IP3R-based FRET sensors. GFP-PHD binds to both PIP2 and IP3; thus it has been thought that changes in [IP3]i could be monitored indirectly by the release of membrane-bound GFP-PHD (9). IP3R-based FRET biosensors consist of the ligand-binding domain of IP3R and a pair of fluorescent proteins, cyan fluorescent protein and yellow fluorescent protein. Since the successful monitoring of IP3 with LIBRA (12), the first IP3R-based FRET biosensor, several different groups have used similar biosensors for IP3 monitoring (11, 13, 14). In principle, quantitative measurements of [IP3]i are not possible with GFP-PHD. In addition, it is recognized that GFP-PHD may be released from the plasma membrane by decreases in available PIP2 (15), which could be attributed to PIP2 hydrolysis or the occupation by other molecules. IP3R-based FRET biosensors offer significant benefits for monitoring IP3 based on their high selectivity for IP3 and ratiometric measurement.

In this study, we developed a series of improved IP3 biosensors that exhibit high pH stability and varying IP3 affinities. They also possess higher selectively and afford a larger dynamic range than that of original LIBRA. In combination with these new biosensors, we developed a method for quantitating IP3 dynamics in single living cells, and we applied this method to measure IP3 dynamics during Ca2+ oscillations.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Media—Hanks' balanced salt solution with Hepes (HBSS-H) contained 137 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 1.3 mm CaCl2, 0.41 mm MgSO4, 0.49 mm MgCl2, 0.34 mm Na2HPO4, 0.44 mm KH2PO4, 5.5 mm glucose, 20 mm Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.4). Intracellular-like medium (ICM) contained 125 mm KCl, 19 mm NaCl, 10 mm Hepes-KOH (pH 7.3), 1 mm EGTA, and 330 μm CaCl2 (for 50 nm free Ca2+).

Plasmid Construction—Venus, EYFP with F46L, F64L, M153T, V163A, and S175G, was constructed using site-directed mutagenesis of pEYFP-N1 (Clontech) and a QuikChange® II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers 1-6 were used for mutagenesis (all primers used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S1). The sequence of the Venus construct (pVenus-N1) was verified by DNA sequencing.

To construct pH-stable LIBRA (LIBRAvIII), the portion of LIBRA containing the membrane-targeting signal, enhanced cyan fluorescent protein, the IP3-binding domain of the rat type 3IP3R (amino acids 1-604), and NheI and EcoRI sites at either end was amplified by PCR using primers 7 and 8 and LIBRA plasmid as the template. This PCR product was then ligated into the NheI and EcoRI sites of pVenus-N1.

To construct LIBRA variants with type 1 IP3R (LIBRAvI), the IP3-binding domain of the rat type 1 IP3R (amino acids 1-604) with XhoI sites incorporated at both ends was amplified by PCR using primers 9 and 10 and a rat brain cDNA library as the template. This PCR product was then ligated into the linker region XhoI site in the LIBRAvIII plasmid. In a similar way, we constructed LIBRAvII with the IP3-binding domain of the rat type 2 IP3R (amino acids 1-604) using primers 11 and 12 and a rat parotid cDNA library as the template. The high affinity variant of LIBRAvIII (LIBRAvIII with mutation R440Q; LIBRA-vIIIS) was prepared by site-directed mutagenesis of the ligand-binding domain of LIBRAvIII using primers 13 and 14. In a similar way, the high affinity variant of LIBRAvII (LIBRAvIIS) was prepared by site-directed mutagenesis of LIBRAvII using primers 15 and 16. Some PCR errors were identified within the IP3-binding domain of LIBRAvI, LIBRAvII, and LIBRAvIIS. Nucleotide sequences of these constructs were corrected by site-directed mutagenesis, and the corrected sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

We previously constructed an IP3-insensitive mutant (K507A) of LIBRA, which we referred to as LIBRA-N. The IP3-insensitive variant of LIBRAv (LIBRAvN) was constructed by cutting the mutated IP3-binding domain of LIBRA-N-plasmid with XhoI and ligating the fragment into LIBRAvIII-plasmid cut with the same enzyme.

Cell Culture and Transfection—COS-7 cells, obtained from RIKEN Cell Bank (Tokyo, Japan), were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with low glucose (1000 mg/liter), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 584 mg/liter l-glutamine, 110 mg/liter sodium pyruvate, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen). HSY-EA1 cell was subcloned from HSY human parotid cell line, a generous gift from Dr. Mitsunobu Sato (Tokushima University, Japan), by a dilution plating technique. HSY-EA1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Eagle's medium nutrient mixture Ham's F-12 (Sigma) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum, 2 mm glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, as described previously. These cells were grown in fibronectin-coated experimental chambers consisting of plastic cylinders (7 mm in diameter) glued to round glass coverslips.

Measurement of Fluorescence—Cells were washed with HBSS-H and rested for at least 5 min prior to experiments. In some experiments, cells were incubated at room temperature for 1-2 min in HBSS-H containing 2.5 μm fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (Dojin Chemicals, Kumamoto, Japan). Permeabilization was performed by applying ICM containing 100 μg/ml (w/v) saponin (ICN, Cleveland, OH) for 1-1.5 min. In some experiments, cells were permeabilized with ICM containing 200 μm β-escin (Sigma). Fluorescence images were captured using a dual wavelength ratio imaging system (Hamamatsu photonics, Shizuoka, Japan) consisting of a C9100-13 EM-CCD camera and W-View optics coupled to a Nikon TE2000 inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a Nikon S Fluor 60 oil immersion objective (NA 1.3). Fluorescence of IP3 biosensors was monitored with excitation at 425 nm and dual emission at 480 and 535 nm. Fluorescence of fura-2 was monitored with sequential excitation at 345 and 380 nm and emission at 535 nm. AQUACOSMOS 2.6 software (Hamamatsu Photonics) and ImageJ program were used for image analyses. To minimize the effect of photobleaching on the estimation of [IP3]i, time-dependent decreases in the fluorescence intensities at two emission wavelengths (480 and 535 nm) were monitored for 5-10 min prior to the stimulations, and the photobleaching rates were calculated by fitting the data to linear or exponential equations.

Determinations of Kd and Hill Coefficient—Data were analyzed by simulated annealing procedure with GOSA-fit software (BIO-LOG, Toulouse, France) to fit the data to Equation 1,

|

(Eq.1) |

where C is the IP3 concentration; Emax is the maximal effect (100%), and n is the Hill coefficient.

Estimation of [IP3]i—To estimate resting [IP3]i, emission ratios of LIBRAvIIS in intact cells before (Rrest) and after (Rmin) treatment with U73122, and emission ratios in the absence (Rmin′) and presence (Rmax′) of saturating concentrations of IP3 were monitored after permeabilization. [IP3]i can be calculated by Equation 2,

|

(Eq.2) |

where ΔR is Rrest - Rmin; ΔRmax is (Rmax′-Rmin′) Rmin Rmin′-1; Kd is the apparent dissociation constant, and n is the Hill coefficient. Because the variability of resting [IP3]i was reasonably small, we used averaged resting [IP3]i to determine Rmin by Equation 3,

|

(Eq.3) |

where Erest is the E (% max) of resting [IP3]i, which is given by Equation 1. [IP3]i was then calculated using Equation 2.

Determinations of Response Rate—LIBRAvIIS-expressing COS-7 cells were permeabilized with saponin, and changes in emission ratio were monitored with the first acquisition protocol (20-50 ms/frame). The response rate for the IP3-dependent increase in ratio was examined by application of 10 μm IP3 to the experimental chamber containing saponin-treated LIBRA-vIIS-expressing cells. To examine the rate of decrease in ratio due to the removal of IP3, permeabilized LIBRAvIIS-expressing cells were initially exposed to 1 μm IP3, and subsequently washed out using IP3-free ICM. In this experimental condition, ∼70% of medium was replaced by a single wash. Using a non-linear least squares method, these data were fitted by the equation derived from a solution of the chemical reaction model, Equation 4,

|

(Eq.4) |

where R0 is the emission ratio at time 0 (the time when the medium in the chamber was replaced); t is the time after the replacement of the medium; Rt is the emission ratio at time t; and A, C, and γ are arbitrary constants. This equation yields the time for the half-maximal increase or decrease in ratio as t½ = γ-1 ln(2 - C-1). Note that this model is based on the assumption that medium (ICM with or without IP3) within the permeabilized cell is replaced completely at t = 0, whereas the actual time for the replacement is later than at t = 0. It is therefore expected that actual t½ values are at least less than those calculated with this method. See details in the supplemental material.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

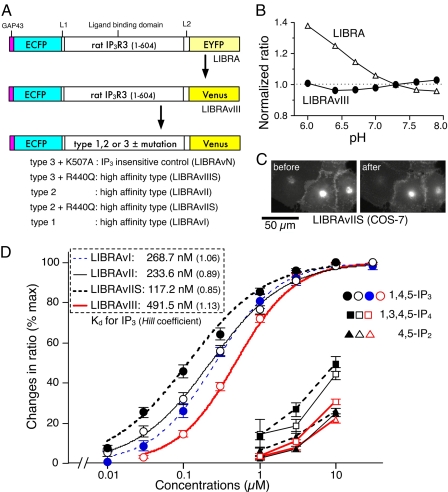

Characterization of Improved IP3 Biosensors—Fig. 1A shows schematic diagrams of IP3 biosensor domain structures. To improve the pH stability of the LIBRA emission ratio (480/535 nm), EYFP was replaced with Venus, a pH-stable yellow fluorescent protein mutant (16). The resulting construct (LIBRAvIII) showed strong pH stability in the range of pH 6-8 (Fig. 1B). Next the LIBRAvIII ligand-binding domain was replaced with that of type 1 or type 2 IP3R, to create high affinity IP3 biosensors. These constructs were designated LIBRAvI and LIBRAvII, respectively. It is known that changing Arg to Gln at position 441 (R441Q) increases the affinity of type 1 IP3R (17). To further increase the affinity, comparable amino acid substitutions in type 2 and type 3 IP3Rs (R440Q) (18) were made in LIBRAvII and LIBRAvIII. We also generated IP3-insensitive LIBRAv (LIBRAvN) by substituting Ala for Lys at position 508 (K508A) in the IP3-binding domain of LIBRAvIII. These biosensors were distributed on the plasma membrane and in vesicular structures (Fig. 1C), and most of the associated fluorescence (>90%) was retained after permeabilization.

FIGURE 1.

Characteristics of IP3 biosensors. A, schematic representations of domain structures of LIBRA and LIBRAv variants. IP3 biosensors consist of a membrane-targeting signal (GAP43); the ligand-binding domain of rat IP3R types 1, 2, or 3 (amino acids 1-604); enhanced cyan fluorescent protein, EYFP, or Venus; and linkers (L1 and L2). K507A and R440Q denote amino acids substitutions of the ligand-binding domain of the IP3R types 2 and 3. B, effects of pH on fluorescence emission ratios of LIBRA and LIBRAvIII. Emission ratios (480 nm/535 nm) of LIBRA and LIBRAvIII in permeabilized COS-7 cells were measured in ICM at various pH values. Emission ratios were normalized to the ratio at pH 7.3. C, fluorescent images of LIBRAvIIS-expressing COS-7 cells before and after permeabilization. D, concentration-response curves for inositol phosphates. Changes in emission ratio of LIBRAv variants because of exposure to various concentrations of IP3 (circle), IP2 (triangle), and IP4 (square) were measured in permeabilized COS-7 cells (LIBRAvIII, LIBRAvII, and LIBRAvIIS) or in permeabilized HSY-EA1 cells (LIBRAvI). Changes in emission ratio were normalized to the effects of IP3 saturation with 10 μm (for LIBRAvI, -II, and -IIS) or 30 μm (for LIBRAvIII) IP3.

To quickly characterize these new candidate biosensors, we examined changes in emission ratios in permeabilized cells in response to stepwise increases in IP3 concentration (supplemental Fig. S1). The results of this preliminary characterization indicated that the apparent affinities were LIBRA ≈ LIBRAvIII < LIBRAvIIIS ≈ LIBRAvI ≈ LIBRAvII < LIBRAvIIS, and the extent of maximal changes in the emission ratios of LIBRAvIII, LIBRAvIIIS, LIBRAvII, and LIBRAvIIS were ∼2-fold larger than that of LIBRA. We also noticed that LIBRAvI worked well in HSY-EA1 cells (supplemental Fig. S1G) but not in COS-7 cells (supplemental Fig. S1D).

Concentration-response curves of the new IP3 biosensors for IP3, inositol 4,5-bisphosphate (IP2), and inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate (IP4) are shown in Fig. 1D. The apparent Kd values of LIBRAvIII, LIBRAvI, LIBRAvII, and LIBRAvIIS for IP3 were 491.5, 268.7, 233.6, and 117.2 nm, respectively. A high concentration (10 μm) of IP2 or IP4 induced 20-40% of the maximal response of these biosensors, and the estimated Kd values of LIBRAvIII, LIBRAvII, and LIBRAvIIS for IP2 and IP4 were estimated (supplemental Table S2). LIBRAvII and LIBRAvIIS exhibited greater selectivity than LIBRA, and the selectivity of LIBRAvIIS for IP3 was 300-fold higher than for IP2 and 96-fold higher than for IP4.

The characteristics of our IP3 biosensors include the use of Venus, ligand-binding domains of different IP3R isoforms, and a membrane-targeting signal. The superior selectivity of IP3R-based FRET sensors provides a clear advantage over GFP-PHD sensors. In addition, utilizing Venus for a FRET-based biosensor is particularly important to avoid pH-related artifacts (16, 19).

The ligand-binding domain of IP3Rs is composed of two functional domains, the amino-terminal suppressor domain and the carboxyl-terminal IP3-binding core domain (17). Unlike other IP3R-based FRET sensors (11, 13), LIBRA and LIBRAv variants contain both IP3 suppressor and core domains. Because the molecular properties of IP3R isoforms have been studied extensively, it is relatively easy to construct biosensors with appropriate levels of affinity. In addition, it has been reported that structural differences in the suppressor domains contribute to functional diversity in ligand sensitivity among IP3R isoforms (20), assuming that the ligand-binding properties of the LIBRAv series reflect this feature of IP3R isoforms. We previously reported a method using LIBRA for determining IP3R ligands (21), and we identified novel ligands of IP3Rs from newly synthesized cyclopentane derivatives (22). This method could be extended easily for identifying subtype-specific ligands of IP3Rs by using a series of new LIBRAv variants.

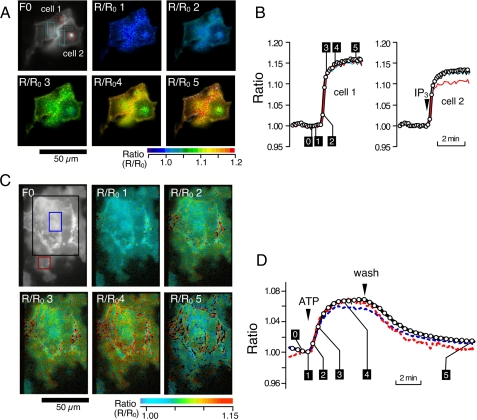

Imaging of IP3-dependent Response of LIBRAvIIS—Emission ratios within an individual cell, whether intact or permeabilized, were uneven, whereas the magnitudes of the maximal change in ratio in response to 10 μm IP3 were reasonably consistent (supplemental Fig. S2). Therefore, we visualized IP3-dependent changes in the fluorescence emission ratio with normalized ratio images (Fig. 2A), where each ratio image was divided by an image before the application of IP3. The normalized LIBRAvIIS emission ratio increased homogeneously except for the area including intracellular vesicles in cell 2 (Fig. 2B). It was noticed that abundant accumulation of IP3 sensors on intracellular vesicles tended to decrease the extent of IP3-dependent changes in the emission ratio. We then applied this procedure to visualize the ATP-induced increase in LIBRAvIIS emission ratio and subsequent decrease because of the removal of ATP in intact COS-7 cells (Fig. 2, C and D).

FIGURE 2.

Image analysis of LIBRAvIIS fluorescence in permeabilized and intact cells. Permeabilized (A and B) and intact COS-7 cells (C and D) were exposed to 10 μm IP3 and 10 μm ATP, respectively. A and C, F0, fluorescence image; R/R0 1-5, images of normalized emission ratio. Ratio images were normalized by the ratio image at time point 0 in B or D. B and D, IP3-induced changes in normalized emission ratios. IP3 or ATP was applied and washed out at the times indicated by the arrowheads in B or D. Numbers in B and D correspond to the numbers on each image in A and C, respectively. Thin colored lines in B and D are normalized ratios in areas shown by same color in the fluorescence images (F0), and thick black lines are values of each cells.

Response rates of IP3 biosensors were examined by high speed monitoring of IP3-dependent changes in the emission ratio of LIBRAvIIS in permeabilized cells and a least squares curve-fitting technique. The emission ratio increased to the half-maximal level in ∼100 ms following the application of 10 μm IP3. The estimated time for the half-maximal increase (t½on) and decrease (t½off) in the emission ratio was 162 and 169 ms, respectively (supplemental Fig. S3). These analyses indicate that the response rate of LIBRAvIIS is sufficiently rapid to reflect responses that occur ∼100 ms or longer. However, the spatial resolution and signal to noise ratio necessary to detect subcellular difference in the high speed monitoring of IP3 were not achieved in our experimental system.

Inclusion of a membrane-targeting signal provided a rapid means for examining biosensors expressed in permeabilized cells (supplemental Fig. S1) and enabled calibration of FRET signals in single cells (Fig. 3). However, nonuniform distributions of biosensors caused a subcellular variability in the ratio. This variability was overcome by using normalized emission ratio images, although this method is not suitable for measurements in motile cells. Further improvement of IP3 biosensor dynamic ranges is required for the high speed monitoring of subcellular IP3 responses.

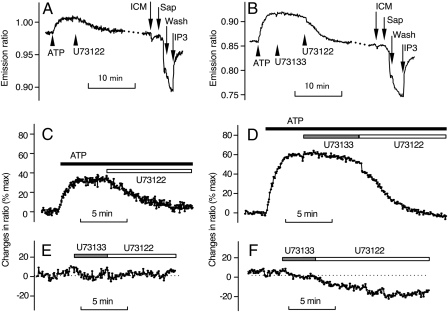

FIGURE 3.

Quantitative analysis of changes in fluorescence ratio of LIBRAvIII and LIBRAvIIS. COS-7 cells expressing either LIBRAvIII (A) or LIBRAvIIS (B) were treated with 10 μm ATP and subsequently with 5 μm U73122. To obtain the maximal change in emission ratio, cells were washed with ICM, permeabilized with saponin (Sap) (100 μg/ml), and exposed to saturating concentrations of IP3 (10 or 30 μm). Effects of 10 μm ATP and U73122 depicted in A and B are shown as % max in C and D, respectively. Effects of U73133 (5 μm) and U73122 (5 μm) on emission ratios of LIBRAvIII (E) and LIBRAvIIS (F) in intact unstimulated cells are shown.

Methods for Quantitative Measurement of [IP3]i—Emission ratios of LIBRAvIII and LIBRAvIIS in intact cells increased upon the application of 10 μm ATP, and returned to basal levels after the addition of 5 μm U73122 (Fig. 3). These reagents did not change the emission ratio of LIBRAvN (data not shown). To obtain the maximal changes in emission ratio (ΔRmax) in each individual cell, cells were permeabilized and exposed to IP3 following the completion of measurements in intact cells (Fig. 3, A and B). Biosensor-expressing cells and LIBRAvN-expressing cells showed decreases in their fluorescence ratios upon permeabilization. These changes in fluorescence are thought to be due to effects on the fluorescent proteins rather than to effects on the IP3-binding domain, and thus they are unlikely to interfere with IP3-dependent changes in emission ratios.

In Fig. 3, C and D, changes in emission ratios are quantitatively shown as % of maximal change in ratio (% max). The difference in % max values of ATP-induced changes in emission ratios between LIBRAvIII and LIBRAvIIS is thought to reflect the difference in affinities of these IP3 sensors. We further examined resting [IP3]i by treating unstimulated cells with U73122. The LIBRAvIII emission ratio did not change with U73122 treatment (Fig. 3E), whereas the LIBRAvIIS ratio decreased slowly to a new steady state (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that the emission ratio of LIBRAvIIS reflects the resting [IP3]i, and U73122 decreases [IP3]i to levels below the detectable range of LIBRAvIIS. Consistent with this interpretation, Sato et al. (13) reported that U73122-induced decreases in the emission ratio of intact cells were observed using a high affinity IP3 biosensor. Based on this idea, we used the U73122-induced decrease in emission ratios, Kd, and Hill coefficient of LIBRAvIIS (shown in Fig. 1D) to estimate the resting [IP3]i in COS-7 and HSY-EA1 cells. U73122-induced decrease in emission ratio of LIBRAvIIS in COS-7 and HSY-EA1 cells was 13.67 ± 0.96 (mean ± S.E., n = 60) and 16.03 ± 1.53 (n = 19), respectively. The estimated resting [IP3]i in COS-7 and HSY-EA1 cells was 15.09 ± 1.38 and 18.16 ± 2.49 nm, respectively. Resting [IP3]i values allowed us to accurately calculate agonist-induced changes in [IP3]i. In calculations for LIBRAvIIS, omitting adjustment for resting [IP3]i caused a noticeable underestimation in concentration (Fig. 4D), whereas the effects of adjusting calculations for resting [IP3]i was limited for LIBRAvIII (Fig. 4C). In addition, the impact of basal noise of the LIBRAvIIS fluorescence on the basal level of calculated [IP3]i was negligible (Fig. 4D, arrowhead), indicating that LIBRAvIIS is suitable for monitoring small increases in [IP3]i up to 200 nm. Changes in the emission ratio of LIBRAvIII corresponded well over a broad range of [IP3]i, up to ∼400 nm, whereas base-line value fluctuations near the resting [IP3]i produced a noticeable difference in the estimated [IP3]i (Fig. 4C, arrowheads). These results indicate that LIBRAvIII is convenient for monitoring broad ranges of [IP3]i.

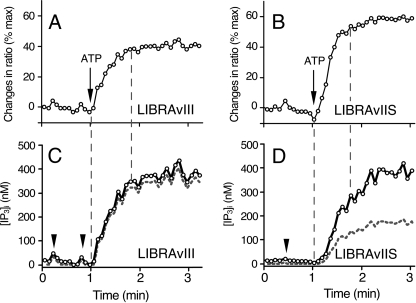

FIGURE 4.

Estimation of [lsqb]IP3]i with LIBRAvIII and LIBRAvIIS. ATP-induced changes in emission ratios of LIBRAvIII (A) and LIBRAvIIS (B) in intact COS-7 cells are shown. These % max values were converted to [IP3]i in C and D, with (solid lines) or without (dashed lines) adjustment for the resting [IP3]i.

In this study, [IP3]i was estimated under the following assumptions: 1) that the properties of IP3 biosensors in permeabilized cells are comparable with those in intact cells, and 2) that U73122 reduces [IP3]i below the detectable level of the biosensors. To examine possible effects of cytosolic proteins on biosensor response, we compared IP3-induced changes in the ratios of LIBRAvIIS in β-escin-permeabilized cells and in saponin-permeabilized cells and found comparable IP3-induced responses (supplemental Fig. S4). β-Escin-permeabilized cells have been used to examine the functions of cytosolic proteins,3 whereas cytosolic proteins are lost in saponin-permeabilized cells (7, 23). Thus, the effects of endogenous cytosolic proteins on the IP3-induced response of biosensors could be ruled out. In addition, our previous study indicates that IP3-dependent changes in the ratio of LIBRA are not altered by Ca2+ or ATP, and that the effect of pH on fluorescent proteins does not alter the IP3-dependent changes in the fluorescence of LIBRA (12). Although these experiments do not exclude possible effects of other small endogenous molecules, it is reasonable to assume at this stage that IP3-dependent changes in the ratios of these types of biosensors in permeabilized cells are comparable with those in intact cells.

We also examined the effects of U73122 on ATP-induced Ca2+ responses, and we found that the pretreatment of COS-7 cells with 5 μm U73122 completely blocked the rise in [Ca2+]i obtained by 3 μm ATP, and strongly decreased responses obtained with 10 μm ATP (data not shown). It is therefore thought that U73122 pretreatment is sufficient to block the low level of PLC activity in unstimulated cells. Indeed, we have used this method to estimate the [IP3]i required to elicit Ca2+ responses (see below), and these values are reasonably close to the threshold concentration of photoreleased [IP3]i (60 nm) that triggers Ca2+ spikes in Xenopus oocytes (24).

Changes in [IP3]i during Agonist-induced Ca2+ Oscillations—The mechanism responsible for Ca2+ oscillations and the associated dynamics of IP3 have been of long-standing interest (2). Experiments based on the translocation of GFP-PHD have suggested that [IP3]i oscillate (9, 10), whereas an IP3R-based FRET biosensor has shown that IP3 accumulates gradually in the cytosol with little or no fluctuation during Ca2+ oscillations (11). Because of conflicting data and a lack of quantitation of IP3 dynamics, it remains controversial whether [IP3]i truly fluctuates and whether proposed [IP3]i fluctuations drive Ca2+ oscillations. To clarify these important questions, we quantitatively monitored IP3 dynamics during Ca2+ oscillations using LIBRAvIIS.

The upper panels of Fig. 5, A-D, show changes in emission ratios of LIBRAvIIS and fura-2, and the lower panels indicate calculated [IP]i during ATP-induced Ca2+ oscillations. In COS-7 cells, stimulation with either 1 or 3 μm ATP increased [IP3]i slowly to a sustained level without detectable fluctuations, and Ca2+ oscillations were observed during this increase and sustained elevation of [IP3]i (Fig. 5, A and B). Unlike ATP-induced increases in [Ca2+]i, the large increase in [Ca2+]i caused by ionomycin (2 μm) treatment had no effect on the emission ratio of LIBRAvIIS, indicating that Ca2+ itself does not activate IP3 generation in COS-7 cells.

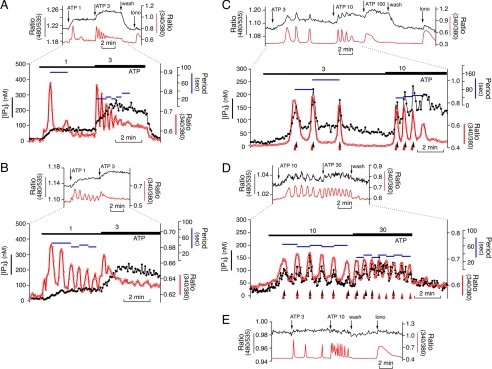

FIGURE 5.

IP3 dynamics during Ca2+ oscillations in COS-7 and HSY-EA1 cells. LIBRAvIIS-expressing cells were loaded with fura-2 and sequentially stimulated with various concentrations of ATP. A and B, COS-7 cells showed no detectable fluctuation in [IP3]i during ATP-induced Ca2+ oscillations. Traces are representative of 27 oscillating cells. C and D, HSY-EA1 cells showed repetitive IP3 spikes during ATP-induced Ca2+ oscillations. Traces are representative of 31 of 55 oscillating cells. Upper traces of each panel show emission ratios of LIBRAvIIS (black lines) and excitation ratios of fura-2 (red lines). Lower traces show estimated [IP3]i (black lines), excitation ratio of fura-2 (red lines), and interspike periods of Ca2+ oscillations (blue lines). E, there is no change in emission ratio of LIBRAvN during ATP-induced Ca2+ oscillations in HSY-EA1 cells. Concentrations of ATP (μm) are shown in each panel. Black arrowhead, peak of IP3 spike; red arrowhead, peak of Ca2+ spike; Iono, 2 μm ionomycin.

We also examined IP3 dynamics in HSY-EA1 cells. This cell line is characterized by long lasting Ca2+ oscillations in response to wide ranges of agonist concentrations (23, 25). In fact, 65% of HSY-EA1 cells (55 of 84 cells) exhibited Ca2+ oscillations following treatment with 3-100 μm ATP or 10-100 μm carbachol. Interestingly, 56% of Ca2+-oscillating HSY-EA1 cells (31 cells) showed associated fluctuations in LIBRAvIIS emission ratios (Fig. 5, C and D). Similar fluctuations in the LIBRAvIIS emission ratio were observed when IP3 dynamics were examined in the absence of fura-2 loading (data not shown). In contrast, no change in emission ratio was observed during Ca2+ oscillations in LIBRAvN-expressing HSY-EA1 cells (Fig. 5E). These experiments exclude the possibility of resulting artifacts derived from IP3-independent changes in LIBRAvIIS fluorescence and possible interference by fura-2 fluorescence. These results demonstrate cell type-specific differences in IP3 dynamics, nonfluctuating rises in [IP3]i and repetitive IP3 spikes in COS-7 cells and HSY-EA1 cells, respectively. Quantitative examinations revealed that repetitive IP3 spikes in HSY-EA1 cells occurred concomitantly with a slow basal accumulation of [IP3]i. The size of IP3 spikes varied from 10 to 100 nm, and the second and later spikes were initiated before the decline of [IP3]i to resting levels, resulting in a slow increase in the [IP3]i interspike.

It is generally thought that IP3 diffuses rapidly within the cell, and thus we think that the fluorescence of membrane-bound biosensors reflects overall cytosolic [IP3]i. In agreement with this idea, we observed nonfluctuating IP3 responses in COS-7 cells and repetitive IP3 spikes in HSY-EA1 cells in both cytosolic and nuclear areas using a biosensor lacking the membrane targeting sequence.3

Although repetitive IP3 spikes were observed in HSY-EA1 cells, our observations do not support the requirement of IP3 fluctuations in Ca2+ oscillations. Although [IP3]i showed clear fluctuations at the beginning of Ca2+ oscillations, repetitive spikes of [IP3]i were gradually obscured during Ca2+ oscillations in 64% of HSY-EA1 cells. In addition, the [IP3]i spike peak was preceded by a Ca2+ spike peak (Fig. 5, C and D). These results suggest that repetitive IP3 spikes in HSY-EA1 cells are passive reflections of the Ca2+ oscillations, and are unlikely to be essential for driving Ca2+ oscillations.

[IP3]i fluctuations could be induced by the effects of Ca2+ on IP3 synthesis and/or IP3 degradation. Applications of 2 μm ionomycin had little or no effect on the emission ratio of LIBRAvIIS in HSY-EA1 cells (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the direct effect of Ca2+ on IP3 production is very small or absent in this cell line. Thus, [IP3]i fluctuations are likely to be caused by Ca2+-induced potentiation of agonist-dependent IP3 generation. The IP3 spikes described here resemble the pattern predicted by the oscillator model, in which positive feedback via Ca2+-dependent activation of PLC is added to the dual positive and negative feedback effect of Ca2+ on IP3R, rather than the model including negative feedback via Ca2+-dependent IP3 degradations by IP3 3-kinases (26).

Ca2+ oscillations were observed primarily when [IP3]i was less than 300 nm (Fig. 6, A and B). More than 50% of COS-7 cells exhibited Ca2+ oscillations when [IP3]i was 50-100 nm, and the percentage of oscillating COS-7 cells decreased as [IP3]i increased (Fig. 6C). In HSY-EA1 cells, Ca2+ oscillations were observed in 50-70% of cells, when interspike [IP3]i was less than 250 nm, and the percentage of oscillating cells decreased abruptly (11.1%) when interspike [IP3]i was greater than 250 nm (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that low concentrations of IP3 (<100 nm) induce Ca2+ oscillations in both cell types, whereas HSY-EA1 cells are more likely to exhibit Ca2+ oscillations at higher concentrations of [IP3]i (100-250 nm) than are COS-7 cells. Large increases in [IP3]i (>250 nm) induced the peak plateau-type Ca2+ response in both cell types.

FIGURE 6.

[Isqb]IP3]i in Ca2+-oscillating and Ca2+-nonoscillating cells. Cells were stimulated with various concentrations of ATP or carbachol, and [IP3]i in individual COS-7 (A) and HSY-EA1 cells (B) were plotted with distinction of Ca2+ oscillations (red circle), peak plateau-type response (open square), or no response (blue triangle). C and D show [IP3]i histograms for the % of oscillating COS-7 (C) and HSY-EA1 cells (D).

This study showed the time delay of IP3 spike peaks from Ca2+ spike peaks in HSY-EA1 cells, and Ca2+ oscillations with nonfluctuations of [IP3]i in COS-7 cells. Together these results suggest it is likely that IP3 spikes are not essential to drive Ca2+ oscillations. Regarding the mechanism of Ca2+ oscillations, the importance of dual feedback effects of Ca2+ on IP3Rs has been demonstrated experimentally (6-8). However, it has been pointed out that this dual feedback effect explains relatively short period Ca2+ oscillations, but it cannot reproduce long interspike intervals. Thus, additional mechanisms responsible for establishing these oscillations remain unclear (3, 26, 27). One model study reported that frequency properties of oscillation are modulated by the incorporation of Ca2+ activation of PLC into the Ca2+ oscillation model based on dual feedback regulations of IP3R properties, which enhances the range of frequency encodings of agonist stimulations (26). Interestingly, HSY-EA1 cells exhibited Ca2+ oscillations for a wider range of agonist and [IP3]i concentrations than observed in COS-7 cells. Thus, it may be possible that repetitive IP3 spikes or fluctuations play some role in supporting and/or regulating Ca2+ oscillations. The quantitative information provided here would be useful for future studies of the mechanisms and roles of IP3 oscillations.

Effect of [IP3]i on the Refractory Period of Ca2+ Oscillations—We analyzed the effects of [IP3]i on the interspike period of Ca2+ oscillations. In COS-7 cells, increases in agonist concentrations resulted in either shortening of interspike periods of Ca2+ oscillations (Fig. 5A) or shifting of oscillations to the peak plateau-type Ca2+ response (Fig. 5B) in association with increases in [IP3]i. Similarly, in HSY-EA1 cells, the interspike period of Ca2+ oscillations appeared to be correlated inversely with the increase in interspike levels of [IP3]i rather than the spike peak level (Fig. 5, C and D). These observations agree with observations that the refractory period of Ca2+ oscillations is controlled by [IP3]i (7, 8).

However, interspike periods of Ca2+ oscillations occurring during a slow rise in [IP3]i were not shortened by the rise in [IP3]i (Fig. 5, A and C). Small increases or no change in interspike periods during an increase in [IP3]i was observed in 18 of 55 HSY-EA1 cells and in 12 of 25 COS-7 cells. These data suggest that IP3 is an important, but not exclusive, regulator of Ca2+ oscillation frequency.

Although the mechanism underlying the dissociation of the interspike period from the rise in [IP3]i is unknown, it might be associated with decreases in IP3R sensitivity. Consistent with this idea, Matsu-ura et al. (11) described progressive decreases in apparent IP3 sensitivity for generation of Ca2+ spikes during Ca2+ oscillations. It is known that Ca2+ within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum regulates IP3R sensitivity. Thus, a slow rise in [IP3]i may be balanced by a decrease in IP3R sensitivity via a slow decrease in stored Ca2+ (28). In addition, the involvement of stored Ca2+ and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase activity in determining the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations has been proposed recently (27). Additional work is required to explore the possible involvement of stored Ca2+ and other cytosolic factors in controlling the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations.

In summary, we developed improved IP3 biosensors and a relatively simple method for the quantitative measurement of [IP3]i, and we applied this method for monitoring IP3 dynamics during Ca2+ oscillations. This method revealed cell type-specific differences in IP3 dynamics as follows: nonfluctuating rises in [IP3]i and repetitive IP3 spikes. Our results provide the first quantitative information for repetitive IP3 spikes and present new aspects concerning the regulation of Ca2+ oscillation frequency. In addition, the method demonstrated here offers a powerful means for studying the IP3 dynamics of many cellular processes.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research 16390532 (to A. T.), by HAITEKU (2007) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and the Japan Science and Technology Agency. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1-S4 and Tables S1 and S2.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; EYFP, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein; GFP-PHD, green fluorescent protein-tagged pleckstrin homology domain of phospholipase C-δ; HBSS-H, Hanks' balanced salt solution with Hepes; ICM, intracellular-like medium; IP2, inositol 4,5-bisphosphate; IP3R, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; IP4, inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PLC, phospholipase C; [IP3]i, cytosolic concentration of IP3; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer.

A. Tanimura, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Berrige, M. J., Lipp, P., and Bootman, M. D. (2000) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1 11-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dupont, G., Combettes, L., and Leybaert, L. (2007) Int. Rev. Cytol. 261 193-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sneyd, J., Tsaneva-Atanasova, K., Reznikov, V., Bai, Y., Sanderson, M. J., and Yule, D. I. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 1675-1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Young, G. W., and Keizer, J. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89 9895-9899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer, T., and Stryer, L. (1991) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 20 153-174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakui, M., Potter, B. V. L., and Petersen, O. H. (1989) Nature 339 317-320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanimura, A., and Turner, R. J. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 30904-30908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajnóczky, G., and Thomas, A. P. (1997) EMBO J. 16 3533-3543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirose, K., Kadowaki, S., Tanabe, M., Takeshima, H., and Iino, M. (1999) Science 284 1527-1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nash, M. S., Schell, M. J., Atkinson, P. J., Johnston, N. R., Nahorski, S. R., and Challiss, R. A. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 35947-35960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsu-ura, T., Michikawa, T., Inoue, T., Miyawaki, A., Yoshida, M., and Mikoshiba, K. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 173 755-765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanimura, A., Nezu, A., Morita, T., Turner, R. J., and Tojyo, Y. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 38095-38098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato, M., Ueda, Y., Shibuya, M., and Umezawa, Y. (2005) Anal. Chem. 77 4751-4758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Remus, T. P., Zima, A. V., Bossuyt, J., Bare, D. J., Martin, J. L., Blatter, L. A., Bers, D. M., and Mignery, G. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 608-616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Wal, J., Habets, R., Várnai, P., Balla, T., and Jalink, K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 15337-15344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagai, T., Ibata, K., Park, E. S., Kubota, M., Mikoshiba, K., and Miyawaki, A. (2002) Nat. Biotechnol. 20 87-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshikawa, F., Morita, M., Monkawa, T., Michikawa, T., Furuichi, T., and Mikoshiba, K. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 18277-18284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blondel, O., Takeda, J., Janssen, H., Seino, S., and Bell, G. I. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 11356-11363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyawaki, A. (2003) Dev. Cell 4 295-305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwai, M., Michikawa, T., Bosanac, I., Ikura, M., and Mikoshiba, K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 12755-12764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nezu, A., Tanimura, A., Morita, T., Shitara, A., and Tojyo, Y. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1760 1274-1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang, L., Huang, W., Tanimura, A., Morita, T., Harihar, S., DeWald, D. B., and Prestwich, G. D. (2007) Chem. Med. Chem. 2 1281-1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanimura, A., Nezu, A., Morita, T., Hashimoto, N., and Tojyo, Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 29054-29062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker, I., and Ivorra, I. (1992) Am. J. Physiol. 263 C154-C165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tojyo, Y., Tanimura, A., Nezu, A., and Morita, T. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1539 114-121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Politi, A., Gaspers, L. D., Thomas, A. P., and Höfer, T. (2006) Biophys. J. 90 3120-3133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berridge, M. (2007) Biochem. Soc. Symp. 74 1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanimura, A., and Turner, R. J. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 132 607-616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.