Abstract

Laminins that possess three short arms contribute to basement membrane assembly by anchoring to cell surfaces, polymerizing, and binding to nidogen and collagen IV. Although laminins containing the α4 and α5 subunits are expressed in α2-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy, they may be ineffective substitutes because they bind weakly to cell surfaces and/or because they lack the third arm needed for polymerization. We asked whether linker proteins engineered to bind to deficient laminins that provide such missing activities would promote basement membrane assembly in a Schwann cell model. A chimeric fusion protein (αLNNd) that adds a short arm terminus to laminin through the nidogen binding locus was generated and compared with the dystrophy-ameliorating protein miniagrin (mAgrin) that binds to the laminin coiled-coil dystroglycan and sulfatides. αLNNd was found to mediate laminin binding to collagen IV, to bind to galactosyl sulfatide, and to selectively convert α-short arm deletion-mutant laminins LmΔαLN and LmΔαLN-L4b into polymerizing laminins. This protein enabled polymerization-deficient laminin but not an adhesion-deficient laminin lacking LG domains (LmΔLG) to assemble an extracellular matrix on Schwann cell surfaces. mAgrin, on the other hand, enabled LmΔLG to form an extracellular matrix on cell surfaces without increasing accumulation of non-polymerizing laminins. These gain-of-function studies reveal distinct polymerization and anchorage contributions to basement membrane assembly in which the three different LN domains mediate the former, and the LG domains provide primary anchorage with secondary contributions from the αLN domain. These findings may be relevant for an understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of laminin deficiency states.

Basement membranes are specialized cell-adherent extracellular matrices consisting primarily of laminins, collagen IV, nidogens, and the heparan sulfate proteoglycans agrin and perlecan (for review, see Ref. 1). Among these, the laminins constitute a family of heterotrimeric glycoproteins that are essential for the assembly of basement membrane scaffolds (2, 3). One property of laminin thought to be critical for basement membrane assembly is that of its anchorage to cell surfaces, a process that appears to be mediated through the LG domains of the α-subunit. Deletion of the five laminin-111 LG domains or of LG domains 4-5 that contain dystroglycan and sulfatide binding loci or excess inhibiting LG4-5 fragment was found to result in a failure of basement membrane assembly in an experimental Schwann cell model (4-6). These studies further suggested that the reason laminin anchorage is crucial is that it provides the key linkage between the cell surface and the extracellular matrix scaffolding such that the other basement membrane components become tethered through laminin.

A second property of laminin is its polymerization into a network-like scaffolding (7, 8). Laminin-111 (α1β1γ1), the most extensively studied in this regard, self-assembles in a thermally reversible manner with an initial oligomer-forming step followed by a calcium-dependent multimer-forming step (7). Laminin fragment and domain loss-of-function analyses have provided evidence that polymerization requires the participation of all three (α, β, and γ) LN domains located at the N termini of the short arms (6, 9) such that laminins that possess fewer domains (as seen with truncated α3 and α4-laminins) lack the ability to polymerize (6, 10).

A third property of laminin found to contribute to basement membrane assembly and stability is that of the binding of nidogen-1 and nidogen-2 (11-13). The nidogen-1 interaction is mediated between the laminin γ1-LEb3 domain and the nidogen G3 domain. Nidogen G2 and G3 domains, in turn, bind to collagen IV. Although many basement membranes do not exhibit an absolute requirement of this bridging interaction, it appears likely that the interaction increases basement membrane stability (14-16).

The principal laminins of Schwann cell endoneurial and skeletal muscle sarcolemmal basement membranes contain the α2-subunit (17). The absence of this subunit found in laminins 211 and 221 has been shown to cause a congenital muscular dystrophy and peripheral neuropathy in humans (classified as type MDC1A) and in mice (for review, see Ref. 18). Both defects have been corrected by transgenic expression of full-length laminin α1 subunit, indicating interchangeability of the α1 and α2 chains (19, 20). A characteristic of α2 laminin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy is a compensatory increase in the laminin α4 subunit both in nerve and muscle. The assembly and functions of α4-laminin in basement membrane are not well understood. The protein is thought to be non-polymerizing with low affinity binding for α-dystroglycan, sulfatides, and α6β1 and α7β1 integrins (21, 22). Improved muscle function in laminin-deficient dystrophic mice, but not improved nerve function, was observed with transgenic expression of a internal domain-truncated muscle agrin (23, 24) that binds to laminin and to α-dystroglycan (Denzer et al. 45 and Gesemann et al. 35). Although it is likely that the benefit of effect depends on these interactions, it is less clear whether amelioration of the muscle phenotype is due primarily to the enhancement of α4-laminin adhesion, to alterations of sarcolemmal α5-laminin, or to some other effect.

Cultured Schwann cells have provided a useful model with which to study basement membrane assembly (4-6). Studies revealed that the galactosyl sulfatide present on the surface of these cells plays an important role in basement membrane anchorage through their binding to laminins, enabling laminin-dependent signaling through dystroglycan and β1-integrins (5, 25). Furthermore, both laminin LN and LG domains were found to be required for laminin assembly of Schwann cell surfaces either in the absence or presence of nidogen and collagen IV (6). Interestingly, neither β1-integrins nor dystroglycan was required for laminin anchorage during initial basement membrane assembly on these cells (5). These receptors may instead act to link (and hence stabilize) the basement membrane to the underlying cell cytoskeleton (26).

In the current study we asked whether laminin deficits of polymerization resulting from LN domain deletions and/or deficits of cell surface binding resulting from LG-domain deletions could be corrected with laminin-binding proteins that add back missing domain activities. Such synthetic protein reagents could provide analytical tools to help understand the role of different domains in basement membrane assembly with the potential for the development of therapeutic approaches. Because there is a nidogen-binding site on laminin γ1 chain near the intersection of the 3 short arms, we designed a chimeric protein (αLNNd) containing the N-terminal α1 LN-LEa domains attached to nidogen-1 G2-rod-G3 domains. We evaluated the capacity of this synthetic short arm to bind laminin and provide type IV collagen binding in lieu of the nidogen it replaces and compared its behavior in a Schwann cell model of basement membrane assembly with that of muscle (non-neural) miniagrin. The fusion protein was found to specifically facilitate polymer formation and basement membrane accumulation of N-terminal-truncated α1-laminins on cultured Schwann cells, whereas miniagrin corrected adhesion deficits.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Constructs—Expression vectors for the mouse laminin α1, human β1, and human γ1 subunits, for deletions of α1LN, α1LN-L4b, α1LG1-5, β1LN and γ1LN, and for chick non-neural miniagrin (mAgrin)3 have been previously described (6, 27-30). The cDNA for αLN-Nd was generated from α1-wtNm (McKee et al. (6)) and NdIIIpCEP-Pu (a gift of Takako Sasaki). The 5′ section containing the LN-LEa of α1 laminin, the bm40 signal peptide, c-Myc epitope tag, and enterokinase cleavage site was generated with primers 1F, 5′-ctgtcaagcttgccaccatgcgcggcagcggcac-3′, and 2r, 5-cacaagtctgctgacagacaccagag-3′. The G2-rod-G3 portion of nidogen for the C-terminal part of αLN-Nd was generated with primers 2f 5′-ctctggtgtctgtcagcagacttgtg-3′ and 1r 5′-taggaggagccactgtactc-3′. Both fragments were joined using the 1f and 1r primers, digested with HindIII-SbfI, and ligated into NdIIIpCEP-Pu. The intact open reading frame of αLNNd was moved via a SpeI-NotI digest to a pcDNA3.1Zeo vector (Invitrogen). The cytomegalovirus promoter and 5′-untranslated region was replaced by a ClaI-HindIII insert from the α1-wtNm vector. To generate the α1rLG1-5Nm construct, α1-wtNm was digested with SapI-BlpI and ligated with a PCR product using primers SapI 1f, 5′-gctgcacaagacaccctaacacag-3′, and BlpI 1r, 5′-gtcagctcagctcacgcttgtttccgg-3′, from α1-wtNm. α1rLN-rLG1-5Nm was generated by replacing a NheI-BsrGI fragment of α1rLG1-5Nm with a NheI-BsrGI fragment from rLNα1Nm. PCRs were carried out using Jumpstart Taq (Sigma P2893) or Roche Applied Science extend long PCR in an Eppendorf Mastercycler. Restriction enzymes (Fermentase; fastdigest), SV gel PCR clean up (Promega), T4 DNA HC ligase (Invitrogen), calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolabs), and XL10 gold Escherichia coli cells (Stratagene) were used according to the manufacture's instructions.

Recombinant and Native Proteins—Plasmids containing laminin subunits were stably transfected into HEK293 cells followed by selection of stable clones as described (6). Plasmids containing αLN-Nd, a1rLN-rLG1-5Nm (designated Δ(αLN&LG)), α1rLG1-5Nm (here shortened to ΔLG), and mAgrin (N25C9500, a gift of Markus Ruegg) were stably transfected into HEK293 cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All other laminin cell lines (LmΔαLN-L4b, LmΔαLN, LmΔβLN, LmΔγLN, and the laminins in which the γ1LN domain was replaced with α1LN or β1LN, i.e. Lmγ1∑α1LN, Lmγ1∑β1LN) and mouse nidogen-1 (pCisNid; gift of Rupert Timpl) were generated as previously described (6).

A stable cell line expressing αLNNd was supplemented with zeocin at 100 μg/ml, whereas recombinant laminin lines were supplemented with puromycin, zeocin, and G418 at a final concentration of 1, 100, and 500 μg/ml, respectively. Immunoprecipitation, SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis of secreted protein was used to confirm expression of trimeric laminin, αLNNd, nidogen-1, and mAgrin in the stable cell lines.

The α1, β1, and γ1 laminin chains were detected with antibodies specific for myc (Roche Applied Science), hemagglutinin (Roche Applied Science), and FLAG (Sigma) epitopes, respectively. Nidogen-1 and αLNNd were confirmed with anti-entactin (Chemicon MAB1946). The αLNNd protein was initially purified on heparin-agarose (Sigma H6508), eluted with 0.5 m NaCl in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, concentrated in an Amicon Ultra-15 filter (Millipore, 100,000 molecular weight cutoff), and dialyzed in a 20 mm phosphate, 1 m NaCl buffer. αLN-Nd as well as nidogen were finally purified by metal chelating chromatography as described (Fox et al. (11)) and dialyzed in TBS-50 (50 mm Tris, 90 mm NaCl, pH 7.4, 0.125 EDTA).

mAgrin was purified on His-select nickel affinity gel (Sigma P6611) with a 250 mm imidazole, 300 mm NaCl, 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, then concentrated and dialyzed as described above. Recombinant laminin was purified from media using heparin-agarose (Sigma) and FLAG M2-agarose as previously described (McKee et al. (6)).

Co-purified laminin and αLN-Nd were isolated directly on FLAG M2-agarose and prepared as above. Type IV collagen and laminin-111 were extracted from lathyritic mouse EHS tumor and purified as described (31).

Protein Concentrations—EHS-laminin concentrations were determined by absorbance (280 nm) as described (9) with molarity determined based on the protein mass of 710 kDa. Absorbance was also used to measure the concentration of αLNNd and mAgrin with masses of 156 and 125 kDa, respectively. Protein mass and molar concentrations of laminins containing domain deletions (LmΔLG, 605 kDa; LmΔαLN, 682 kDa; LmΔαLN-L4b, 558 kDa; LmΔ(αLN&LG), 577 kDa) were determined by gel densitometry of their Coomassie Blue-stained bands compared with those of EHS-laminin with corrections as needed for decreased mass.

Laminin Polymerization Assay—Aliquots (50 μl) of laminin without or with αLNNd in polymerization buffer were incubated at 37 °C, sedimented to separate polymerized protein, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as previously described in detail (6). The apparent critical concentration was calculated from the product of x intercept and slope (10).

Assay of αLNNd Binding to Laminin and Collagen-IV—One μg of recombinant laminin or collagen-IV was bound to a 96-well flat-bottomed dish (Nunc) in 40 mm sodium carbonate buffer overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 1 mg/ml BSA in phosphate-buffered saline and 0.06%Triton X-100, then incubated with 2-fold increasing amounts of αLNNd or nidogen (0.013-16 μg/ml). Protein was detected by entactin-specific (i.e. nidogen-1) monoclonal antibody (Chemicon MAB1946), protein A-horseradish peroxidase (Sigma P8651), and o-phenylenediamine (Sigma P3888). To determine collagen binding to αLNNd- or nidogen-bound laminin, one μg of recombinant laminin was coated onto a 96-well flat bottomed dish following by blocking with BSA and 5 μg/ml nidogen or αLNNd incubation for 1 h at room temperature. After 3 washes with phosphate-buffered saline and 0.06%Triton X-100, increasing amounts of collagen-IV (0.01-10 μg/ml) were added for 1 h at room temperature. Bound collagen was detected with collagen-IV-specific anti-body (Chemicon AB 756P), protein A-horseradish peroxidase (Sigma P8651), and o-phenylenediamine (Sigma P3888) with absorbance measured at 492 nm with a TECAN Spectrafluor plate reader.

Sulfatide Binding Assay—HSO4-3Galβ1-1′Ceramide (brain galactosyl sulfatides) and galactosyl ceramide (Sigma C4905) were dissolved in methanol, and 0.1 μg was added per immulon-1B microtiter well (ThermoLab systems). The plate was dried overnight at room temperature, and the wells were washed and blocked with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay blocking buffer (1% BSA in TBS-50/Ca2+). Proteins in varying concentrations in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay blocking buffer were added to each well and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Protein binding was detected with a horseradish peroxidase-linked monoclonal FLAG antibody (Sigma) and o-phenylenediamine (Sigma) with absorbance at 492 nm on a TECAN Spectrafluor.

Cell Culturing—Schwann cells isolated from sciatic nerves from newborn Sprague-Dawley rats were the kind gift of Dr. James Salzer (New York University). These cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini Bio Products), neuregulin (0.5 μg/ml, Sigma), forskalin (0.2 μg/ml, Sigma), 1% glutamine, and penicillinstreptomycin. Cells at passages 11-17 were plated onto 24-well dishes (Denville) and treated with the indicated proteins for 1 h at 37 °C followed by washing and fixation. For electron microscopy (see the supplemental data) cells were plated in 60-mm Permanox dishes (Nalgene, Nunc) 2 days before the addition of proteins.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy—Schwann cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline and fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Immunofluorescence analysis was conducted as previously described (6). Briefly, cultures were blocked with goat serum and then stained with primary and secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescent probes. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for laminin-111 β1LN-LEa (anti-E4) and α1LG4-5 (anti-E3, 1/500) were used as described (4, 6, 32). Nidogen epitopes were stained with entactin monoclonal reagent (1/100). mAgrin and Myc-tagged laminins were stained with chick agrin (1/1000;30) and Myc (1/100) antibodies, respectively. Detection of bound primary antibodies was accomplished with Alexa Fluor 488 and 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) at 1:500 and 1:100, respectively, and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgM at 1:100 (Jackson Immuno-Research) and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (32). Laminin, αLNNd, mAgrin, collagen IV, and nidogen-1 immunofluorescence levels were quantitated from digital images recorded with IPLab 3.7 software (Scanalytics) as described (6). A segmentation range was chosen to subtract background and accellular immunofluorescence. The sum of pixels and their intensities in highlighted cellular areas of fluorescence were measured and normalized by dividing by the number of cells for each image. Data were expressed as the mean and S.D. of normalized summed intensities SigmaPlot and SigmaStat (Jandel).

Rotary-shadowed Pt/C Replicas—Rotary shadow laminins (25-50 μg/ml in 0.15 m ammonium bicarbonate, 60% glycerol) were sprayed onto mica discs, evacuated in a BAF500K unit (Balzers), rotary-shadowed with 0.9 nm Pt/C at an 8° angle, and backed with 8-nm carbon at a 90° angle as otherwise described (9).

RESULTS

The domain and subunit composition of proteins used in this study are shown in Fig. 1. The proteins mAgrin, αLNNd, and LmΔ(αLN&LG) were characterized and compared with LmΔαLN and wt Lm-111 by SDS-PAGE after purification.

FIGURE 1.

Recombinant αLNNd and mAgrin. Panel A, αLNNd and mAgrin. The chimeric protein αLNNd is composed of the N-terminal LN and LEa domains of the laminin α1 subunit (containing laminin polymerization (P) activity) fused to the C-terminal G2, LE, and G3 domains of nidogen-1 (containing type IV collagen-binding (C4) and laminin γ1-binding (Lm) activities). The internally truncated protein mAgrin consists of the laminin coiled-coil binding NtA domain fused through the first follistatin (FS) domain to the dystroglycan and sulfatide binding (DG/S) terminal laminin-like LG and LE domain complex. Panel B, Coomassie Blue-stained gels (SDS-PAGE, 8% acrylamide, reducing conditions) of mAgrin, αLNNd, LmΔ(αLN&LG), LmΔαLN, and (wt) laminin-111. Panel C, diagrammatic representations of the recombinant heterotrimeric laminins used in this study.

Molecular Morphology—αLNNd, mAgrin, LmΔαLN-L4b, and wild-type (wt) laminin-111 alone and in complexes were visualized in electron micrographs after Pt/C rotary shadowing (Fig. 2). αLNNd molecules had the appearance of three globular domains separated by two short rods in either an extended or bent configuration. LmΔαLN-L4b molecules had the appearance of a laminin with two rather than three short arms. After incubation of this laminin with αLNNd, a third short arm-like structure could be seen attached to the laminin from one of the two short arms near the junction of the other arms (Fig. 2, arrows), rendering laminin complexes not unlike (wt) laminin-111. mAgrin Pt/C replicas had the appearance of a flexible rod and globular protein in which four sphere-like structures could often be appreciated. After incubation of laminin-111 with mAgrin, the long arm (coiled-coil domain) was often seen to have a short projecting stub at about the mid-point along its length (arrows).

FIGURE 2.

Rotary-shadowed Pt/C replicas. Electron micrographs (shown contrast reversed) and corresponding schematic renditions of αLNNd (upper row panels), LmαΔLN-L4b (second row), complexes of αLNNd-LmαΔLN-L4b (third row), mAgrin (MA, fourth row), and complexes of mAgrin-laminin are shown. αLNNd adds a third short arm structure to the β1 and γ1 short arms of the truncated two-armed LmαΔLN-L4b, whereas mAgrin projects out from the long arm with its LG complex farthest from the coiled-coil.

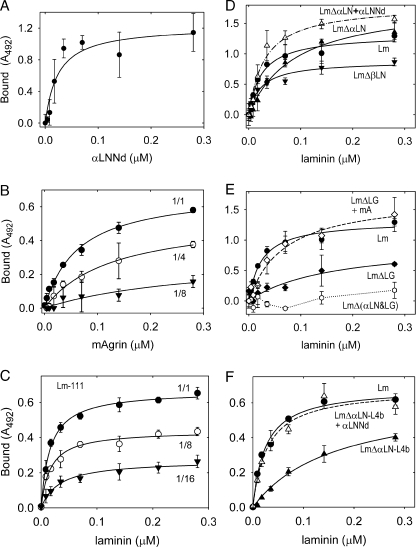

Binding Interactions of αLNNd—The chimeric protein was designed to possess three activities, i.e. binding of the C-terminal G3 domain to the laminin γ1 domain LE3b, binding of domains G2 and G3 to type IV collagen, and the laminin α1-short arm component of polymerization that resides in the LN domain. Purified chimeric protein was evaluated for its ability to bind to laminin-111 and to type IV collagen (Fig. 3) in solid phase assays and found to bind to both. Chimeric αLNNd and nidogen-1 bound in an almost identical manner (apparent KD of 0.29 and 0.26 nm, respectively). αLNNd also bound to type IV collagen with an apparent Kd of 4.0 nm (compared with 1.6 nm for nidogen-1). The ability of αLNNd was compared with that of nidogen-1 to mediate attachment of laminin to nidogen (ternary complex). αLNNd did this (KD of 1.4 nm) similar to nidogen-1 (1.4 nm).

FIGURE 3.

Binding of αLNNd to laminin-111 and type IV collagen. Panel A shows plots of the binding of αLNNd (closed circles) and nidogen-1 (Nd, open circles) to immobilized laminin-111 with bound protein detected at 492 nm after treatment with nidogen-specific antibodies (average and S.D., n = 3). No binding (single measurements) was detected with laminin-111 (closed triangles) or nidogen-1 (open triangles) on albumin (BSA)-coated wells. Data fitted for single-ligand binding (fitted half-maximal binding of 0.3 nm for αLNNd and nidogen-1). Panel B shows plot of the binding of αLNNd (closed circles) and nidogen-1 (open circles) to immobilized type IV collagen (average and S.D., n = 3). Half-maximal binding was fitted to 4 nm for αLNNd and 1.6 nm for nidogen-1. No binding (single measurements) was detected on BSA-coated wells. Panel C shows plots of type IV collagen binding to immobilized laminin-111 (through ternary complexes) mediated by the presence of either αLNNd (closed circles) or nidogen-1 (open circles) applied at constant concentration (33 nm). Coated wells were incubated with type IV collagen at the indicated concentrations followed by determination of bound protein (average and S.D., n = 3). Half-maximal binding was fitted and found to be 1.4 nm for αLNNd and 1.5 nm for nidogen-1. Chimeric αLNNd, like nidogen-1, showed binding activity for both laminin and type IV collagen and was able to mediate formation of ternary complexes.

The next question addressed was whether αLNNd, when bound to a laminin with two short arms, would mediate laminin polymerization (Fig. 4). This was evaluated in a standard self-assembly assay (37 °C) in which the products are separated by sedimentation and evaluated by SDS-PAGE (6, 10). LmΔαLN-L4b did not form a polymer when incubated alone. However, when LmΔαLN-L4b and αLNNd were incubated in increasing equimolar concentrations, they co-sedimented in the polymer fraction in a concentration-dependent fashion with apparent critical concentrations (0.06 and 0.08 μm) similar to that observed with laminin-111 (0.07 and 0.08 μm). αLNNd did not appear to adversely affect the polymerization of (wt) laminin-111 (critical concentration of 0.06 μm) despite the addition of a fourth short arm creating a laminin complex with two α1LN domains. Incubation of LmΔβLN or LmΔγLN with αLNNd did not enable polymerization. This was interpreted as evidence that αLNNd is only able to rescue a polymerization deficit arising from deletion resulting in loss of the αLN domain (LmΔαLN and LmΔαLN-L4b).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of αLNNd on the polymerization of laminins with shortarm deletions. Recombinant laminins alone or mixed with equimolar αLNNd were incubated in the presence of 1 mm calcium at 37 °C followed by centrifugation, SDS-PAGE, and densitometry quantitation of Coomassie Blue intensity of supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions. Panel A, Coomassie Blue-stained gels of the following preparations after incubation: Lm-111, LmΔαLN-L4b + αLNNd (equimolar for all concentrations), Lm-111 + αLNNd (equimolar), LmΔαLN-L4b, LmΔβLN + αLNNd (equimolar), and LmΔγLN + αLNNd (equimolar). Laminin concentrations (mg/ml) are indicated above the supernatant (s) and pellet (p) pairs. Panel B, plots of the fraction of polymer against total laminin concentration for the indicated laminins (both shown and not shown in the above gels) without or with αLNNd. The chimeric fusion protein αLNNd enabled the polymerization of LmΔαLN-L4b and LmΔαLN but not LmΔβLN or LmΔγLN.

Binding of wt Laminin, LmΔαLN-L4b, and mAgrin to Sulfatides—The binding of the agrin NtA domain to the coiled-coil domain of laminin-111 through the γ1-subunit (KD ≈ 2 nm) and of the non-neural agrin LG domains (KD ≈ 2 nm) to α-dystroglycan has been previously described (33-35).

Schwann cells contain galactosyl sulfatide that provides cell surface binding to laminins (5). To determine whether mAgrin and αLNNd bind to sulfatides, these proteins and different recombinant laminins were evaluated with a solid-phase assay (Fig. 5). Fitted half-maximal binding values (apparent KD) were determined for mAgrin (0.06 μm), αLNNd (0.02 μm), (wt) laminin-111 (0.02 μm), LmΔαLN (0.09 μm), LmΔαLN-L4b (0.16 μm), and LmΔ(αLN&LG) (none detected). The binding of LmΔLG was low (0.16 μm) and is deduced to reflect binding largely arising from the αLN domain. However, the measured value was greater than that detected with αLNNd or reported for α1LN/LEa protein fragment (0.04 μm; 36) and may reflect interference arising from other domains of laminin. The addition of mAgrin to LmΔLG increased laminin binding (0.09-0.07 μm), and the addition of αLNNd to LmΔαLN and LmΔαLN-L4b increased the apparent affinities (0.16-0.07 and 0.03 μm, respectively). These changes are thought to primarily reflect the combined contributions arising from adding a second sulfatide binding domain to the mutant laminins possessing one binding domain, rather than polymerization, as detection of contributions of the latter is thought to require mobile lipid molecules reconstituted in a mobile bilayer (37). Binding (half-maximal and maximal) for laminin and (especially) mAgrin were found to be decreased when sulfated-galactosyl ceramide was diluted into non-sulfated galactosyl ceramide. Structural analysis of the laminin α1 LG4 domain has revealed several lysines and arginines that interact with the small sulfatides and is consistent with the hypothesis that each LG domain engages several glycolipid sulfates (38). Therefore, the decreases in binding in the assay may arise from the loss of sulfate charge density available to bind to the LG4 protein patch. Although the sulfatide composition of Schwann cell surfaces has not been determined, it is likely that it much less than 100%, and therefore, the effective laminin and agrin affinities may be lower than that detected with pure lipid. A caveat is that if the sulfatides are organized into compact rafts, the higher affinities could be preserved.

FIGURE 5.

Protein binding to galactosyl sulfatide. The indicated components (single or equimolar pairs) were incubated at the indicated concentrations in lipid-coated wells. Binding was detected with antibodies to laminin (FLAG epitope-horseradish peroxidase), αLNNd (Myc), or mAgrin (agrin). The average and S.D. values (n = 3) and fitted regressions for simple binding (solid and dashed lines) are shown in each graph. Panel A, binding of αLNNd to galactosyl-3-sulfate-ceramide. Panel B, binding of mAgrin to galactosyl-3-sulfate-ceramide undiluted (1/1) or diluted (1/4, 1/8) in galactosyl-ceramide. Panel C, binding of (wt) laminin to galactosyl-3-sulfate-ceramide undiluted (1/1) or diluted (1/8, 1/16) in galactosyl-ceramide. Panel D, Binding of Lm (closed circles), LmΔαLN (closed triangles), LmΔαLN + αLNNd (open triangles), and LmΔβLN (closed inverted triangles). Panel E, Binding of Lm (closed circles), LmΔLG (closed diamonds), LmΔLG + mA (open diamonds), and LmΔ(αLN&LG) (open circles). Panel F, Binding of Lm (closed circles), LmΔαLN-L4b (closed triangles), and LmΔαLN-L4b +αLNNd (open triangles). Contributions fromαLNNd, mAgrin, and laminin LG and αLN domains were detected. Dilution of the sulfated galactosyl ceramide in galactosyl ceramide resulted in decreased binding for mAgrin and laminin. Coupling of αLNNd to LmΔαLN, αLNNd to LmΔαLN-L4b, and mA to LmΔLG increased the laminin affinities.

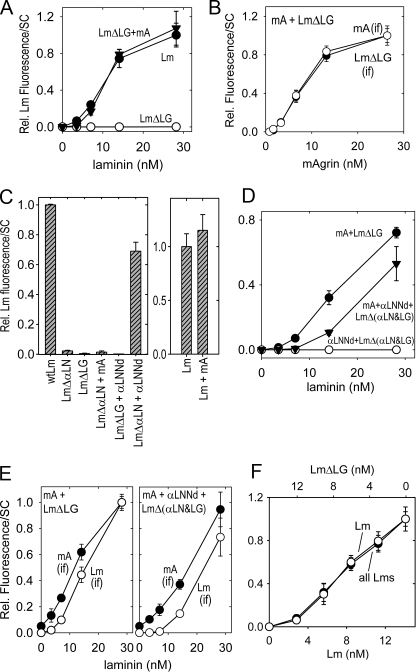

Laminin Accumulation on the Surface of Cultured Schwann Cells—It was previously found that Schwann cells treated with exogenous laminins assemble a thin basement membrane on the free cell surface in a process dependent upon interactions of the LG domains with cell surface sulfatides and upon the ability of laminins to polymerize (5, 6). Laminin assembly was found in turn to enable the incorporation of collagen IV in the presence of nidogen-1. To determine whether αLNNd and mAgrin were capable of affecting laminin assembly on cells through their respective capacities to alter polymerization and adhesive interactions, Schwann cells were incubated with laminins bearing deletions of different domains in either the presence or absence of the above laminin-binding proteins (Figs. 6, 7 and 8).

FIGURE 6.

Laminin and type IV collagen assembly on cell surfaces. Schwann cells were incubated with the indicated components (14 nm each unless otherwise indicated1) for 1 h, washed, fixed, and immunostained for laminin, agrin, nidogen/entactin, and/or collagen IV and counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Panels A, B, E, F, I, and J. Cells were untreated (NT), treated with (wt) laminin, LmΔαLN-L4b, LmΔαLN-L4b + αLNNd, LmΔαLN, and LmΔαLN + αLNNd and immunostained with anti-Lmγ1 (green) antibody. Increased laminin immunofluorescence was detected when αLNNd was coincubated with laminins lacking the αLN domain. Panels M and N, αLNNd was not detected on cells when incubated alone (anti-entactin) but was detected colocalized with laminin when co-incubated with LmΔαLN. Panels C, D, G, and H, cells were treated with LmΔLG, LmΔLG + mAgrin (mA) and stained with antibodies for laminin (anti-Lmγ1, green) or agrin (red). Increased laminin and mA immunofluorescence was detected when mA was incubated with LmΔLG. Panels K and L, cells were incubated with LmΔ(αLN&LG) + mA or with LmΔ(αLN&LG) + mA + αLNNd and stained with antibody for Lm. Increased laminin immunofluorescence was detected when LmΔ(αLN&LG) was co-incubated with mA and αLNNd but not when incubated only with mA. Panels M, and N, αLNNd (M; 14 nm) incubated alone (M, anti-entactin, red; anti-Lmγ1, green) or with LmΔαLN (N; 14 nm). Little αLNNd accumulated on cell surface in the absence of the laminin. Panels O and P, when Myc-tagged laminin (56 nm) was incubated, both Myc and LG4-5 (E3) epitopes were detected. When Myc-tagged LmΔLG (28 nm) was incubated with Myc-free laminin (28 nm), only the LG4-5 epitope (compared with Myc) was detected on the cell surface. Panels Q-V, cells were immunostained for collagen IV (red) after treatment with LmΔαLN-L4b + collagen IV (Col-IV), laminin + Col-IV, LmΔαLN-L4b + Col-IV + nidogen (Nd), laminin + Col-IV + Nd, LmΔαLN-L4b + Col-IV + αLNNd, and laminin + Col-IV + αLNNd. Increased collagen IV was detected with either αLNNd with non-polymerizing laminin or nidogen with either wt or non-polymerizing laminin.

FIGURE 7.

Contribution of αLNNd to laminin accumulation on Schwann cell (SC) surfaces. Cells were cultured with the indicated proteins for 1 h and immunostained for the laminin β1 subunit (E4-specific antibody). Panels A and B, quantitation of laminin (A) and corresponding entactin antigen (B) immunofluorescence summed cell intensities for laminin (Lm, closed circles), αLNNd (constant 26 nm) with increasing LmΔαLN (closed inverted triangles), nidogen-1 (26 nm) with increasing LmΔαLN (open triangles), and LmΔαLN alone (open circles) (average and S.D., n ≥ 5). The addition of αLNNd, but not nidogen-1, to the non-polymerizing LmΔαLN enabled self-assembly to a degree approaching that of intact laminin. Panels C and D, cells were incubated with the indicated proteins (constant 14 nm laminin and 14 nm αLNNd). αLNNd enabled the cell surface assembly of laminins bearing deletions of the αLN domain but not deletions of the βLN or γLN domains.

FIGURE 8.

Contribution of mAgrin to laminin accumulation on Schwann cell (SC) surfaces. Cells were incubated followed by detection of adherent protein as in the Fig. 7. Laminin (panel A) and mAgrin (panel B) immunofluorescence (average and S.D., n = 8) of cells incubated with increasing concentrations of LmΔLG with mAgrin (mA) constant 26 nm; closed inverted triangles), (wild-type) laminin-111 (closed circles), or LmΔLG alone (open circles) is shown. mAgrin co-accumulated with LmΔLG in a concentration-dependent manner. Panel C, left, plot (n = 5) of the indicated laminins (14 nm) incubated alone, with αLNNd (14 nm), or with mAgrin (14 nm). Increased laminin accumulation occurred when non-polymerizing laminin was incubated with αLNNd or when LmΔLG was incubated with mAgrin but not when LmΔαLN was incubated with mAgrin or when LmΔLG was incubated with αLNNd. Right, plot of laminin-111 (14 nm, n = 6) incubated without or with mAgrin (13 nm). Panel D, cell surface accumulation of LmΔ(αLN&LG). The cell accumulation of nonpolymerizing/non-adhesive laminin treated with either αLNNd alone (closed inverted triangles), co-purified with equimolar LmΔ(αLN&LG) or with mAgrin + αLNNd (open triangles) was compared with that of LmΔLG treated with mAgrin (open circles, constant 26 nm). Panel E, laminin (open circles) and mAgrin (closed circles) immunofluorescence were compared for both mAgrin + LmΔLG (left) and mAgrin + αLNNd + LmΔ(αLN&LG) (right). The laminin with combined deletions inactivating polymerization and adhesion could only be rescued with a mixture of αLNNd and mAgrin. The laminin and mAgrin epitopes accumulated together with a near-constant ratio. Panel F, laminin and LmΔLG were varied with respect to each other (summed concentration maintained at 14 nm) and detected with antibody for laminin. LmΔLG was unable to accumulate on cell surfaces even in the presence of wt laminin.

Cells near confluency were incubated for an hour with proteins diluted into the culture medium, washed, fixed, and treated with antibody to laminin followed by detection with a fluorescent secondary reagent. The average cell fluorescent intensities (average and S.D. of sums of pixel intensities/cell) were determined from the antibody-stained images and plotted (Figs. 7 and 8). Treatment of cells with laminin-111 (wt) resulted in the accumulation of laminin (Figs. 6, A and B, and 7A) as reported previously (6). In contrast, treatment with the non-polymerizing laminins LmΔαLN-L4b, LmΔαLN, or the chimeric fusion protein αLNNd (detected with nidogen-specific antibody) resulted in almost no detectable protein (Fig. 6, E and I). However, when LmΔαLN-L4b or LmΔαLN was mixed with αLNNd in equimolar concentrations (14 nm), laminin fluorescence was substantially increased (Fig. 6, F and J, and Fig. 7, A-C) to levels approaching (∼60-70% in different experiments) of (wt) laminin. Laminin accumulation on cells increased as a function of increasing concentration (Fig. 7A) and was accompanied by a corresponding increase in nidogen epitope (B) located on αLNNd. αLNNd was specific in its ability to improve laminin accumulation on cells as it had no appreciable effect when incubated with laminins bearing deletions of the β-LN or γ-LN domains or bearing an incomplete complement of α-, β-, and γ-LN domains or an incomplete set (α-α-β and α-β-β) of domains when combined with αLNNd (Fig. 7C). αLNNd caused a slight increase in wt laminin fluorescence that could be related to the small increase seen in the polymerization slope (Fig. 7D).

The contribution of mAgrin to the accumulation of laminins on Schwann cells was also examined (Figs. 6, C, D, G, and H, and 8). LmΔLG failed to accumulate on cells, even at concentrations as high as 28 nm (Fig. 8A). Similarly, very little mAgrin was detected on cell surfaces when added without laminin (Fig. 6G). In contrast, coincubation of LmΔLG with mAgrin resulted in the accumulation of both laminin and mAgrin (Fig. 6, D and H) in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 8, A and B). The addition of mAgrin to (wt) laminin caused only a slight increase over that seen with the laminin alone (Fig. 8C). On the other hand, the addition of mAgrin to a non-polymerizing laminin did not lead to increased laminin accumulation (Fig. 8D).

The ultrastructure of cells treated with wt laminin, LmΔαLN-L4b, LmΔLG, LmΔαLN-L4b + αLNNd, and LmΔLG + mAgrin was evaluated after incubation of the components (14 nm) for one hour (supplemental Fig. S1). Thin basement membrane-like linear electron-dense matrices (lamina densa), separated from the cell surface by an electron lucid zone (lamina lucida), were detected in lengths of several μm or more after treatment with αLNNd + LmΔαLN-L4b or with mA + LmΔLG that was similar to the matrix formed with (wt) laminin and that was absent after treatment with the defective laminins in the absence of the synthetic linker proteins.

Because there appear to be separate polymerization and adhesive contributions required for laminin assembly on Schwann cell surfaces, it seemed reasonable to expect that a laminin that lacked both an LN domain and LG domains would be able to accumulate on cells only in the presence of both αLNNd and mAgrin. The recombinant laminin LmΔ(αLN&LG) was generated to evaluate this possibility. When LmΔ(αLN&LG), copurified with αLNNd, was incubated with cells, the laminin failed to accumulate at different concentrations (Figs. 6K and 8D). However, when αLNNd-LmΔ(αLN&LG) was also mixed with mAgrin, laminin accumulation was observed on cells (Fig. 6L) in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 8, D and E).

We asked whether laminins lacking LG domains can accumulate on cells by co-polymerization with intact laminins. To address this possibility, LmΔLG (20 μg/ml, Myc-tagged) was mixed with (wt) laminin (20 μg/ml and compared with Myc-tagged (wt) laminin (40 μg/ml). The laminins were co-stained with antibodies to Myc and to LG4-5 (anti-E3). LmΔLG was not detected in the mixture, whereas both wt laminins were detected (Fig. 6, O and P). Furthermore, a colinear increase of total and wt laminin was observed when wt laminin was varied with LmΔLG with the sum of the two laminins maintained constant (Fig. 8F). These data indicate that under the conditions of the assay (below the free solution critical concentration), all laminins are attached to the cell surface through LG domains. It follows that the cell surface extracellular matrix contains a laminin monolayer and that every LmΔLG that accumulates in the presence of mA must be simultaneously bound to mA and anchored to the cell surface.

Because accumulation of collagen IV on Schwann cell surfaces requires laminin, the nidogen-binding site in laminin, and nidogen (6), we asked whether αLNNd would be able to support a collagen IV network on the cell surface (Figs. 6, Q-V, and Fig. 9). Collagen immunofluorescence was detected on cell surfaces after treatment with collagen IV in the presence of either wt laminin with nidogen-1 or non-polymerizing laminin with αLNNd. The collagen levels detected with the latter were substantial (½ to 3/4 of wt laminin plus nidogen). When mAgrin was incubated with LmΔLG, nidogen, and collagen, near-normal (i.e. wt) levels were detected (Fig. 9C). In agreement with earlier observations (6), non-polymerizing laminin, itself retained at very low levels relative to wt laminin, can maintain substantial levels of collagen so long as the nidogen-bridging interaction is preserved. Here αLNNd was able to substitute for nidogen for this activity.

FIGURE 9.

Contributions of αLNNd and mAgrin to type IV collagen accumulation on cells. Schwann cells (SC) were incubated with the indicated laminins (14 nm) and collagen IV (9 nm) without/with αLNNd (14 nm) or nidogen (14 nm). Panel A, comparison of laminin versus collagen IV accumulation and αLNNd versus nidogen contributions (average and S.D., n = 7, each condition). Laminin accumulation in the presence of collagen IV required either a polymerizing laminin or non-polymerizing laminin + αLNNd. Collagen IV accumulation required only a non-polymerizing laminin + nidogen or nonpolymerizing laminin + αLNNd. Panel B, plots of mAgrin and LmΔLG contributions. Type IV collagen accumulation was increased with LmΔLG + mAgrin + nidogen (n = 7). Panel C, mAgrin accumulation required LmΔLG in the presence of nidogen and collagen IV (n = 5). mA, mAgrin.

The chimeric fusion protein αLNNd uses the nidogen-binding site to attach to laminin and, therefore, would be expected to be in competition with any existing nidogen. The effect of such competition was examined in the absence and presence of collagen IV (Supplemental Fig. S2). When αLNNd was varied to molar excess in the presence of 13 nm nidogen-1 and LmΔαLN-L4b, laminin accumulation on cells increased with a plateau reached by ∼25 nm. When nidogen-1 was varied to molar excess over constant 13 nm αLNNd and LmΔαLN-L4b, laminin accumulation decreased with a low plateau reached above ∼25 nm. However, the addition of 9 nm collagen IV dampened this effect such that the addition of molar excess of nidogen caused no appreciable decrease in laminin accumulation. An interpretation compatible with the results is that collagen IV forms a network that can accommodate substantial excess of nidogen or αLNNd, resulting in little apparent competition.

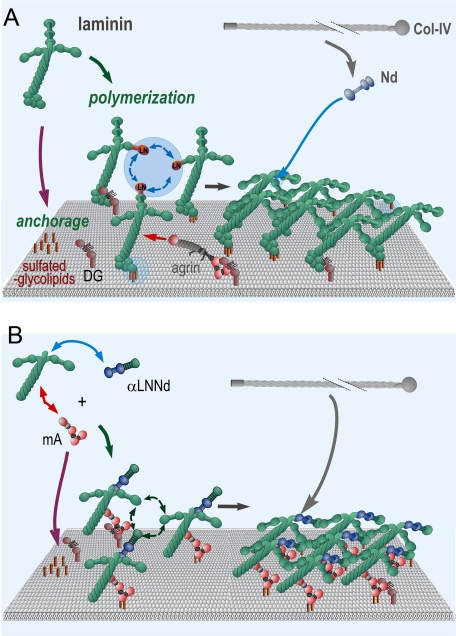

DISCUSSION

A study of two synthetic linker proteins that add functional activities to laminins and restore the ability of deficient laminins to assemble a basement membrane-like extracellular matrix on Schwann cells has provided insights into the mechanisms of basement membrane assembly. A model (Fig. 10) consistent with these findings and supported by our earlier studies is that a laminin initiates assembly by attaching to the cell surface through sulfatides (and also to α-dystroglycan to the degree to which it is present) and by forming linkages among adjacent laminins through polymerization. Nidogen-1 binds to laminin and also to type IV collagen, increasing the surface concentration of the latter and thereby promoting its own polymerization. Agrins further stabilize the laminins by binding to them and to the cell surface.

FIGURE 10.

Basement membrane assembly mediated by intact and polymer/adhesion-deficient laminins. A working model is shown based upon the findings of this and our previous studies. Panel A, laminins (e.g. 111, 211) become anchored through their LG (primary interactions) and αLN (secondary interactions) domains to cell surface sulfatides (abundant) and dystroglycan (less abundant). The α, β, and γ LN domains of different laminin molecules bind to form a polymer. Type IV collagen molecules associate with the laminin polymer primarily through the bridging activity of nidogens, enabling formation of a collagen co-polymer. Panel B, a laminin-deficient in polymerization (here with only two short arms) and cell adhesion activity (here absence of LG domains) could only polymerize if provided synthetic linker proteins with the missing polymerization (αLNNd) and anchoring (mA) activities.

The study adds several elements to our understanding of laminin interactions and assembly. First, the data support, through a gain-of-function analysis, that the laminin polymer is formed by the binding of α,,β and γ LN domains into a ternary domain complex. An absent αLN domain, but not an absent βLN or γLN, could be replaced with the missing αLN domain with restoration of self-assembly. It is interesting that placement of the synthetic linker arm at the nidogen-binding site located in domain LEb3 of the γ-subunit near the intersection of the three short arms created a third arm sufficiently similar to the defective native arm to provide the activity. Furthermore, the internal L4a, LEb, L4c, and LEc of the α-subunit are largely dispensable for polymerization. These internal domains may serve primarily to add length to the short arm, affecting the spacing of laminins within the polymer but might also contribute to polymer stability. Of note, binding of αLNNd to wt laminin, which adds a fourth short arm duplicating the αLN domain, was not deleterious for polymerization and slightly enhanced it. The polymerization slope increase seen with recombinant and to a lesser extent with EHS-laminin may be the consequence of a fractional reduction of activity within the LN domain.

A study of interactions between laminin LN-LEa fragment pairs, in which binding was detected for α1LNLEa-α1LNNEa pairs, led to a less-restricting hypothesis of assembly in which a laminin polymer could form with ternary complexes that lacked an α-β-γ composition (39). However, a subsequent domain loss-of-function analysis conducted with heterotrimeric laminins failed to support this alternative (6). The current study now provides gain-of-function evidence that a strict α-β-γ short arm complex is required. The possibility that the α-α subunit interaction is involved in the attachment between laminin polymer layers rather than polymerization per se presents itself as an interesting alternative hypothesis to explain its self-binding.

The linker protein αLNNd was able to largely, but not completely, restore laminin assembly on cell surfaces when coupled to laminin molecules lacking the αLN domain or entire α-short arm. The incompleteness of the rescue may be a consequence of instability in the recombinant linker protein, incorrectness of the length of the linker placement of αLN to the other LN domains, or a missing contribution from the internal α-short arm domains. Although the lack of change of the critical concentration for the linked laminin compared with wt laminin is more compatible with the first interpretation, further study will be required to resolve the question. Preservation of the type IV collagen binding sites of nidogen G2 and G3 domains within αLNNd allowed for the linked laminin complex to recruit type IV collagen to the cell surface in the absence of nidogen. The ability of nidogen to compete for αLNNd accumulation on cells was considerably reduced in the presence of type IV collagen. mAgrin, an internally truncated protein that binds strongly to the coiled-coil domain of laminin, to sulfatides, and to α-dystroglycan can also enhance basement membrane assembly. In particular, we found that it enables the poorly adhesive laminin LmΔLG to become anchored to the cell surface, assemble, and recruit nidogen and type IV collagen. Anchorage, however, was found to be sufficient for such assembly on Schwann cells only in the presence of LN-mediated polymerization. This limitation was revealed by the specificities of laminin rescue and with a laminin that lacked both an α-LN domain and LG domains with assembly restoration only if mAgrin and αLNNd were coincubated with the doubly truncated LmΔ(αLN&LG).

Earlier analysis of the cultured Schwann cells revealed that sulfatides constitute the principal contribution for laminin anchorage (to be distinguished from signaling contributions) and not α-dystroglycan, β1-integrins, or heparan sulfates 5). In another (breast epithelial) cell line, a greater dystroglycan contribution for laminin accumulation was reported (25). The explanation for the observed differences may lie in the relative surface density of these different molecules, all capable of laminin binding through LG domains, i.e. in Schwann cells there are too few dystroglycan molecules available for laminin binding compared with available sulfatide molecules for dystroglycan to serve as principal anchor. However, it seems a reasonable expectation that in some tissues dystroglycan (notably in muscle) or integrins will be found to serve as the chief anchoring species because of their abundance. The significance of these receptors is that they can link the basement membrane to the underlying cortical cytoskeleton to stabilize the basement membrane-cell interface. mAgrin is an interesting linker protein in that it binds to γ1-laminins, α-dystroglycan, sulfatides, and an integrin and may well be suited to provide an anchorage function for laminins in different cellular environments.

A model refinement to be considered is based on the observations that sulfatide binding contributions also arise from αLN domains (this study and Garbe et al. 36). These domains may provide supplemental adhesion of laminin molecules to the cell surface such that contacts form with both LG and αLN. Nonetheless, adhesion through LG must occur for laminin to accumulate on cell surfaces. Furthermore, polymerization is required in addition to αLN and LG for significant assembly on cell surfaces and cannot be accomplished with laminins that only possess αLN and LG domains.

Both this study and that of McKee et al. (6) have revealed a contribution of type IV collagen and nidogen in which a collagen-rich laminin-poor discontinuous extracellular matrix can form on a cell surface in the absence of laminin polymerization and presence of collagen and nidogen. The collagen levels achieved under these circumstances have been found to be about half that with a polymerizing laminin. In contrast, cell surface of laminin or collagen has not been observed to any appreciable degree with a non-adhesive laminin (without LG domains) on Schwann cells.

In summary, domain-modified laminin-111 proteins were used in this study to identify key self-assembly and anchoring activities that distinguish the two synthetic linker proteins and to analyze their contributions to basement membrane assembly in a model culture system. A question that arises is how predictive are these findings for complex basement membranes of different tissues? Of particular interest, from a human disease standpoint, are the basement membranes of the Schwann cell endoneurium in nerve and the sarcolemma in skeletal muscle. Both of these basement membranes are defective in the MDC1A congenital muscular dystrophies and mouse models that result from null, hypomorphic, and domain-altering mutations of the gene coding for the laminin α2 subunit. Laminin-211 is the principal laminin of these basement membranes. However, α4- and α5-laminins are expressed in the dystrophy (23, 40-42). α4-laminins lack the α-subunit short arm for polymerization and bind less well to α-dystroglycan and sulfatides (21, 22), whereas laminin-511, thought to polymerize, has also reduced binding to these components (43). What then is the basis for a mAgrin rescue of muscle and its failure (so far) to rescue in nerve (23, 24, 40)? One possible explanation for the observation in peripheral nerve is that mAgrin cannot rescue an α2-defect through α4-laminin. The phenotypic rescue in muscle, on the other hand, is substantial. It has been suggested that mAgrin accomplishes this in muscle through its interaction with α4-laminins and dystroglycan (23). This would appear to be a reasonable interpretation if the only defect is in adhesion. However, if laminin polymerization is also important, then the rescue of α4-laminin would be insufficient. An alternative possibility, consistent with the findings of this study, is that the rescue is mediated through α5-laminins, a laminin found to increase in the sarcolemmal basement membrane after mAgin treatment (23). In nerve, there may be too little α5-laminin available for binding to mAgrin to mediate rescue of radial sorting. A caveat to consider in comparing the effects of mAgrin on nerve and muscle is that these tissues may contain different densities of anchors/receptors that could differentially effect a requirement for polymerization. The model does not rule out the possibility that a sufficiently high density distribution of a high affinity surface component could reduce the requirement for polymerization by enabling binding of a sufficiently dense distribution of laminin molecules to form a stable matrix in the absence of the contribution provided by polymerization (6).

A related question is whether αLNNd, like mAgrin, holds potential to ameliorate the radial sorting defect and muscle pathology seen in laminin-α2 deficiency states. The most obvious situation in which one might expect αLNNd to beneficially affect nerve and muscle is with the dy2J dystrophic mouse that arises from an in-frame deletion within the α2LN domain (44). In those variants of the syndrome in which there is little or no laminin α2 expression, one might predict that such amelioration would be less likely, especially if the repair is mediated by binding of αLNNd to laminin-411. The deficit of anchorage for this laminin would remain uncorrected. On the other hand, the combined action of mAgrin and αLNNd might efficiently convert laminin-411 into a strongly adhesive polymerizing laminin.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-NS38469 and R37-DK36425. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs 1 and 2.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: mAgrin, miniagrin; wt, wild type; EHS, Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm; BSA, bovine serum albumin; Pt/C, platinum/carbon.

References

- 1.Yurchenco, P. D., Amenta, P. S., and Patton, B. L. (2004) Matrix Biol. 22 521-538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth, N., Vatansever, H. S., Murray, P., Meyer, M., Frie, C., Paulsson, M., and Edgar, D. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 144 151-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miner, J. H., Li, C., Mudd, J. L., Go, G., and Sutherland, A. E. (2004) Development 131 2247-2256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsiper, M. V., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115 1005-1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, S., Liquari, P., McKee, K. K., Harrison, D., Patel, R., Lee, S., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 169 179-189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKee, K. K., Harrison, D., Capizzi, S., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 21437-21447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yurchenco, P. D., Tsilibary, E. C., Charonis, A. S., and Furthmayr, H. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260 7636-7644 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yurchenco, P. D., Cheng, Y. S., and Colognato, H. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 117 1119-1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yurchenco, P. D., and Cheng, Y. S. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 17286-17299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng, Y. S., Champliaud, M. F., Burgeson, R. E., Marinkovich, M. P., and Yurchenco, P. D. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 31525-31532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox, J. W., Mayer, U., Nischt, R., Aumailley, M., Reinhardt, D., Wiedemann, H., Mann, K., Timpl, R., Krieg, T., Engel, J., and Chu, M. L. (1991) EMBO J. 10 3137-3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pöschl, E., Mayer, U., Stetefeld, J., Baumgartner, R., Holak, T. A., Huber, R., and Timpl, R. (1996) EMBO J. 15 5154-5159 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ries, A., Gohring, W., Fox, J. W., Timpl, R., and Sasaki, T. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268 5119-5128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bader, B. L., Smyth, N., Nedbal, S., Miosge, N., Baranowsky, A., Mokkapati, S., Murshed, M., and Nischt, R. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 6846-6856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willem, M., Miosge, N., Halfter, W., Smyth, N., Jannetti, I., Burghart, E., Timpl, R., and Mayer, U. (2002) Development 129 2711-2722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poschl, E., Schlotzer-Schrehardt, U., Brachvogel, B., Saito, K., Ninomiya, Y., and Mayer, U. (2004) Development 131 1619-1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton, B. L., Miner, J. H., Chiu, A. Y., and Sanes, J. R. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139 1507-1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gullberg, D., Tiger, C. F., and Veiling, T. (1999) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56 442-460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gawlik, K., Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y., Ekblom, P., Takeda, S., and Durbeej, M. (2004) Hum. Mol. Genet. 13 1775-1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gawlik, K. I., Li, J. Y., Petersen, A., and Durbeej, M. (2006) Hum. Mol. Genet. 15 2690-2700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talts, J. F., Sasaki, T., Miosge, N., Gohring, W., Mann, K., Mayne, R., and Timpl, R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 35192-35199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishiuchi, R., Takagi, J., Hayashi, M., Ido, H., Yagi, Y., Sanzen, N., Tsuji, T., Yamada, M., and Sekiguchi, K. (2006) Matrix Biol. 25 189-197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moll, J., Barzaghi, P., Lin, S., Bezakova, G., Lochmuller, H., Engvall, E., Muller, U., and Ruegg, M. A. (2001) Nature 413 302-307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiao, C., Li, J., Zhu, T., Draviam, R., Watkins, S., Ye, X., Chen, C., Li, J., and Xiao, X. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 11999-12004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weir, M. L., Oppizzi, M. L., Henry, M. D., Onishi, A., Campbell, K. P., Bissell, M. J., and Muschler, J. L. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 4047-4058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yurchenco, P., and Patton, B. L. (2009) Curr. Pharm. Des., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Yurchenco, P. D., Quan, Y., Colognato, H., Mathus, T., Harrison, D., Yamada, Y., and O'Rear, J. J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 10189-10194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smirnov, S. P., McDearmon, E. L., Li, S., Ervasti, J. M., Tryggvason, K., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 18928-18937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colognato-Pyke, H., O'Rear, J. J., Yamada, Y., Carbonetto, S., Cheng, Y. S., and Yurchenco, P. D. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 9398-9406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smirnov, S. P., Barzaghi, P., McKee, K. K., Ruegg, M. A., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 41449-41457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yurchenco, P. D., and Furthmayr, H. (1984) Biochemistry 23 1839-1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, S., Harrison, D., Carbonetto, S., Fässler, R., Smyth, N., Edgar, D., and Yurchenco, P. D. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 157 1279-1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denzer, A. J., Schulthess, T., Fauser, C., Schumacher, B., Kammerer, R. A., Engel, J., and Ruegg, M. A. (1998) EMBO J. 17 335-343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kammerer, R. A., Schulthess, T., Landwehr, R., Schumacher, B., Lustig, A., Yurchenco, P. D., Ruegg, M. A., Engel, J., and Denzer, A. J. (1999) EMBO J. 18 6762-6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gesemann, M., Brancaccio, A., Schumacher, B., and Ruegg, M. A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 600-605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garbe, J. H., Gohring, W., Mann, K., Timpl, R., and Sasaki, T. (2002) Biochem. J. 362 213-221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalb, E., and Engel, J. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 19047-19052 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison, D., Hussain, S. A., Combs, A. C., Ervasti, J. M., Yurchenco, P. D., and Hohenester, E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 11573-11581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odenthal, U., Haehn, S., Tunggal, P., Merkl, B., Schomburg, D., Frie, C., Paulsson, M., and Smyth, N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 44505-44512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meinen, S., Barzaghi, P., Lin, S., Lochmuller, H., and Ruegg, M. A. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176 979-993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang, D., Bierman, J., Tarumi, Y. S., Zhong, Y. P., Rangwala, R., Proctor, T. M., Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y., Takeda, S., Miner, J. H., Sherman, L. S., Gold, B. G., and Patton, B. L. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168 655-666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patton, B. L., Connoll, A. M., Martin, P. T., Cunningham, J. M., Mehta, S., Pestronk, A., Miner, J. H., and Sanes, J. R. (1999) Neuromuscul. Disord. 9 423-433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu, H., and Talts, J. F. (2003) Biochem. J. 371 289-299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colognato, H., and Yurchenco, P. D. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9 1327-1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denzer, A. J., Gesemann, M., Schumacher, B., and Ruegg, M. A. (1995) J Cell Biol 131, 1547-1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.