Abstract

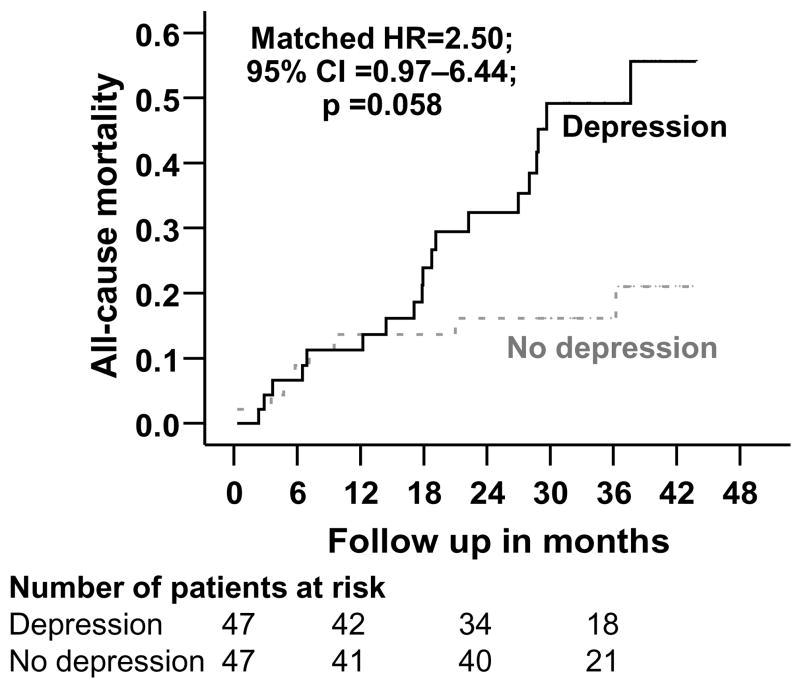

Depression is common in heart failure and is associated with increased mortality. Yet, it is often underdiagnosed and inadequately treated. Lack of disease-specific and easy-to-administer screening tools is one of the reasons for underdiagnosis of depression in heart failure. We examined the effect of depression, as diagnosed by a single question about depression caused by heart failure symptoms and affecting quality of life, in a propensity score matched cohort of heart failure patients. Of the 581 patients enrolled in the quality of life sub-study of the Digitalis Investigation Group trial, 298 (51%) reported that their heart failure prevented them from living as they wanted during the last month by making them feel depressed. Seventy patients (23%) who reported that they felt “much” or “very much” depressed were considered depressed for the purpose of this study. We matched 47 (67%) of these depressed patients with 47 patients from among the 283 patients without depression. Kaplan-Meier and matched Cox regression analyses were used to estimate associations of depression with mortality and hospitalizations during a median follow up of 33 months. Compared with 8 (17%) deaths in patients in the non-depressed group, 19 (40%) of those in the depressed group died from all causes (unadjusted hazard ratio {HR}, 1.55, 95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.004–2.39; p, 0.048). Adjustment for propensity scores (adjusted HR, 1.77, 95% CI, 1.04–3.00; p, 0.034) or other covariates (adjusted HR, 1.85, 95% CI, 1.12–3.04; p, 0.016) did not alter the association between depression and mortality. The association, however, became marginally significant in the matched cohort (HR, 2.50, 95% CI, 0.97–6.44; p, 0.058). There was no significant association between depression and hospitalization. Baseline depression, identified by a single disease-specific question, was associated with increased mortality among ambulatory chronic heart failure patients.

Keywords: Depression, heart failure, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Depression is common in heart failure (HF) and is associated with poor outcomes.1–5 Studies of depression in HF are often restricted to hospitalized acute HF patients and limited by the use of research-oriented screening tools, such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, which are almost never used in clinical practice.1–5 One of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) items asks a direct question about depression caused by HF symptoms.6,7 Such a single question may not identify all patients with depression, but will likely identify the most severe cases of depression, and might be easier to use by busy clinicians. However, the prognostic value of depression assessed in this manner is not well known. Using the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial data we studied the effect of depression as identified by a single question on outcomes in a propensity score matched cohort of ambulatory chronic HF patients.

METHODS

We used a public-use version of the DIG dataset obtained from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The details of the DIG trial have been previously published.8,9 Briefly, 7788 ambulatory chronic HF patients in normal sinus rhythm from 302 centers in United States and Canada were randomized to either digoxin or placebo during 1991-1993.8,9 Of these, 6800 had left ventricular ejection fraction <=45%. Most patients were receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and diuretics. DIG participants were followed for a median of 38 months. Vital status was collected up to December 31, 1995 and was ascertained for 99% of the patients.10

A subgroup of 581 patients participated in the quality of life sub-study and responded to the MLHFQ at baseline. One of the MLHFQ items asks “Did your heart failure prevent you from living as you wanted during the last month by making you feel depressed?6,7 Responses were recorded on a 6-point Likert scale (0=no to 5=very much). Of the 581 patients, 283 responded negatively and 298 patients responded positively. For the purpose of this study, patients (n=70) who felt “much” or “very much” depressed due to their HF symptoms (responses 4 or 5 on the Likert scale) were categorized as having depression. Patients (n=228) who felt “very little” to “somewhat” depressed were excluded from our analysis, resulting in a sample size of 353 patients: 70 depressed and 283 non-depressed.

We then estimated propensity scores for depression for all 353 patients, using a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model (c statistic=0.86), and used that to match 47 depressed patients with 47 patients without depression. Covariates in the model included all baseline patient characteristics in Table 1, as well as clinically plausible interactions.11–13 The propensity score is the conditional probability of receiving an exposure (e.g. to be depressed) given a vector of measured covariates, and can be used to adjust for selection bias when assessing causal effects in observational studies.14–17 Pre-match mean propensity scores for depressed and non-depressed patients were respectively 0.46201 and 0.13307 (absolute standardized difference, 147%; t-test p, <0.0001). After matching, mean propensity scores for depressed and non-depressed were respectively 0.32909 and 0.33373 (absolute standardized difference, 2%; t-test p, 0.919).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics, by depression status, after propensity score matching

| N (%) or mean (±SD) | Not Depressed (N = 47) | Depressed (N = 47) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.26 (±11.53) | 62.32 (±13.09) | .677 |

| Female | 14 (29.8%) | 10 (21.3%) | .344 |

| Non-white | 10 (21.3%) | 8 (17.0%) | .600 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.76 (±6.59) | 28.07 (±6.19) | .599 |

| Duration of HF (months) | 20.32 (±26.28) | 23.64 (±30.96) | .577 |

| Primary cause of HF | |||

| Ischemic | 32 (68.1%) | 32 (68.1%) | .980 |

| Hypertensive | 6 (12.8%) | 5 (10.6%) | |

| Idiopathic | 5 (10.6%) | 6 (12.8%) | |

| Others | 4 (8.5%) | 4 (8.5%) | |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 29 (61.7%) | 32 (68.1%) | .517 |

| Current angina | 22 (46.8%) | 18 (38.3%) | .404 |

| Hypertension | 21 (44.7%) | 21 (44.7%) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 14 (29.8%) | 14 (29.8%) | 1.00 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 17 (36.2%) | 20 (42.6%) | .527 |

| Medications | |||

| Pre-trial use of digoxin | 17 (36.2%) | 16 (34.0%) | .829 |

| Trial use of digoxin | 23 (48.9%) | 17 (36.2%) | .211 |

| ACE inhibitors | 46 (97.9%) | 43 (91.5%) | .168 |

| Non-potassium-sparing diuretics | 39 (83.0%) | 35 (74.5%) | .313 |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 3 (6.4%) | 4 (8.5%) | .694 |

| Potassium supplement | 14 (29.8%) | 13 (27.7%) | .820 |

| Symptoms and signs of HF | |||

| Dyspnea at rest | 14 (29.8%) | 14 (29.8%) | 1.00 |

| Dyspnea on exertion | 39 (83.0%) | 42 (89.4%) | .370 |

| Limitation of activity | 38 (80.9%) | 41 (87.2%) | .398 |

| Jugular venous distension | 3 (6.4%) | 4 (8.5%) | .694 |

| Third heart sound | 6 (12.8%) | 10 (21.3%) | .272 |

| Pulmonary râles | 6 (12.8%) | 7 (14.9%) | .765 |

| Lower extremity edema | 9 (19.1%) | 12 (25.5%) | .458 |

| NYHA functional class, % | |||

| Class I | 7 (14.9%) | 6 (12.8%) | .944 |

| Class II | 18 (38.3%) | 20 (42.6%) | |

| Class III | 19 (40.4%) | 19 (40.4%) | |

| Class IV | 3 (6.4%) | 2 (4.3%) | |

| Heart rate (/minute), | 78.40 (±11.35) | 78.36 (±14.05) | .987 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| Systolic | 126.83 (±17.78) | 127.96 (±19.19) | .768 |

| Diastolic | 74.28 (±10.71) | 76.85 (±12.16) | .279 |

| Chest radiograph findings | |||

| Pulmonary congestion | 7 (14.9%) | 5 (10.6%) | .536 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >0.5 | 28 (59.6%) | 29 (61.7%) | .833 |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 4.34 (±0.39) | 4.31 (±0.44) | .692 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.22 (±0.34) | 1.27 (±0.34) | .448 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 66.43 (±18.84) | 65.30 (±21.45) | .787 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 35.83 (±13.00) | 35.79 (±14.84) | .988 |

We used Kaplan-Meier and matched Cox regression analysis to determine the effect of baseline depression on mortality and hospitalization. Matched Cox regression analysis is a stratified analysis that uses each pair of matched patients as a separate stratum to compare survival within each pair, which is then used to estimate the overall hazard ratio. All statistical tests were evaluated using two-tailed 95% confidence levels, and analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 14.18

RESULTS

The mean (±SD) age of the 94 matched patients was 62 (±12) years, (range 21–92), 25% were women, and 19% were non-whites. Baseline characteristics of the matched cohort are displayed in Table 1.

During a median follow up of 33 months (range, 0.3 to 43.8 months), 27 (29%) patients died from all causes, 22 (23%) due to cardiovascular causes, and 7 (7%) due to worsening HF. Compared with 8 (17%) deaths in patients in the non-depressed group, 19 (40%) of those in the depressed group died from all causes (unadjusted hazard ratio {HR}, 1.55, 95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.004–2.39; p, 0.048; Table 2). Adjustment for propensity scores (adjusted HR, 1.77, 95% CI, 1.04–3.00; p, 0.034) or other covariates (adjusted HR, 1.85, 95% CI, 1.12–3.04; p, 0.016) did not alter the association between depression and mortality. The association between depression and all-cause mortality remained significant in the matched cohort (HR, 2.56, 95% CI, 1.12–5.85; p, 0.026) but bordered on significance when matched Cox regression analysis was used (HR, 2.50, 95% CI, 0.97–6.44; p, 0.058; Table 2). Kaplan-Meier plots for all-cause mortality are displayed in Figure 1. Depression had no associations with cardiovascular or HF mortality.

Table 2.

Association of depression with all-cause mortality

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) | P values | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted, before matching (n=353) | 1.55 (1.004 – 2.39) | 0.048 |

| Adjusted for propensity scores, before matching (n=353) | 1.77 (1.04 – 3.00) | 0.034 |

| Adjusted for covariates,* before matching (n=353) | 1.85 (1.12 – 3.04) | 0.016 |

| Propensity-matched (n=94) | 2.56 (1.12 – 5.85) | 0.026 |

| Propensity-matched, accounted for matching (n=94) | 2.50 (0.97 – 6.44) | 0.058 |

Covariates in the final model included age, sex, race, diabetes, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, lower extremity edema, and serum creatinine.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots for all-cause mortality (HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval)

Hospitalizations due to all causes, cardiovascular causes and worsening HF occurred respectively in 69 (74%), 53 (56%) and 33 (35%) patients. Compared with 34 (72%) all-cause hospitalizations in patients in the non-depressed group, 35 (75%) of those in the depressed group were hospitalized from all causes (HR, 1.15, 95% CI, 0.63 – 2.09; p, 0.648). Depression had no associations with hospitalizations due to cardiovascular causes or worsening HF.

DISCUSSION

In the current analysis, we demonstrate that using a single item question about the presence of depression in the past four weeks caused by HF symptoms, it was possible to identify severely depressed feeling among 12% of patients, which was associated with increased mortality. This is important as it may provide an easy tool for busy clinicians to identify disease-specific depression in ambulatory HF patients who might be at increased risk of death, which may be potentially prevented by appropriate therapeutic interventions.

Our findings are consistent with prior investigations of the relationship between depression and mortality.1–5,19,20 However, our study is distinguished by the use of a single item question to identify patients with depression related to HF symptoms, and the use of propensity score matching. Although the underlying biological and behavioral mechanism by which depression adversely affects survival in HF is not well understood, there are putative explanations. Physiological hypotheses include heightened susceptibility to platelet activation, autonomic dysfunction, an impaired cytokine network, and activated apoptosis signaling molecules.21–23 Other explanatory models have attempted to relate depression in HF to increased mortality via behavioral mechanisms such as poor medication adherence, lack of energy and drive, and a sedentary life style.24,25

Despite the high prevalence of depression among patients with HF, the poor outcomes associated with it, and the safe treatment options available, it is surprising that it remains relatively under-diagnosed and inadequately treated.26 Barriers to effective diagnosis and treatment of depression in HF patients in general, and in elderly HF patients in particular, include patient, provider, and health care system factors. One of the key provider factors is inadequate time to evaluate and treat depression.26 Our findings suggest that a single question related to depressed mood caused by HF symptoms would identify many depressed patients who are at high risk of mortality. Although the aim of this study was not to examine the psychometric properties of the single MLHFQ question relative to established depression scales, it is noteworthy that this single question identified depression in 12% of patients and that depression identified in this way was associated with increased risk of death. Furthermore, this question is unique as it not only identified depression, but also qualified depression as being due to their HF and as having limited their quality of life.

Limitations of our analysis include a modest sample size and lack of validation of depression using an established tool. Misclassification of some potential depressed patients in the non-depressed group is possible. However, we excluded patients with mild to moderate depression, and any random misclassification would likely result in underestimation of the association of depression with mortality. In addition, residual bias and bias due to unmeasured covariates are possible. Finally, patients in our study were relatively younger and predominantly men, with normal sinus rhythm and from the pre-beta-blocker era of HF therapy. Therefore, larger prospective studies in contemporary HF patients are needed to confirm our findings. In conclusion, the presence of depression caused by HF symptoms in the previous four weeks as identified by a single question was associated with increased mortality in ambulatory chronic HF patients. This question may provide clinicians tool for identifying high risk depressed HF patients for appropriate therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

“The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) study was conducted and supported by the NHLBI in collaboration with the DIG Investigators. This Manuscript was prepared using a limited access dataset obtained from the NHLBI and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the DIG Study or the NHLBI.”

Funding/Support: Dr. Ahmed is supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants from the National Institute on Aging (1-K23-AG19211-04) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1-R01-HL085561-01 and P50-HL077100).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Havranek EP, Ware MG, Lowes BD. Prevalence of depression in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:348–50. A9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, Kuchibhatla M, Gaulden LH, Cuffe MS, Blazing MA, Davenport C, Califf RM, Krishnan RR, O’Connor CM. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1849–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumsfeld JS, Jones PG, Whooley MA, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Weintraub WS, Spertus JA. Depression predicts mortality and hospitalization in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150:961–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Junger J, Schellberg D, Muller-Tasch T, Raupp G, Zugck C, Haunstetter A, Zipfel S, Herzog W, Haass M. Depression increasingly predicts mortality in the course of congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedmann E, Thomas SA, Liu F, Morton PG, Chapa D, Gottlieb SS. Relationship of depression, anxiety, and social isolation to chronic heart failure outpatient mortality. Am Heart J. 2006;152(940):e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rector TS, Cohn JN. Assessment of patient outcome with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire: reliability and validity during a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pimobendan. Pimobendan Multicenter Research Group. Am Heart J. 1992;124:1017–25. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90986-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rector TS, Kubo SH, Cohn JN. Validity of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire as a measure of therapeutic response to enalapril or placebo. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:1106–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90582-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Digitalis Investigation Group. Rationale, design, implementation, and baseline characteristics of patients in the DIG trial: a large, simple, long-term trial to evaluate the effect of digitalis on mortality in heart failure. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:77–97. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Digitalis Investigation Group. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins JF, Howell CL, Horney RA. Determination of vital status at the end of the DIG trial. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:726–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed A, Husain A, Love TE, Gambassi G, Dell’Italia LJ, Francis GS, Gheorghiade M, Allman RM, Meleth S, Bourge RC. Heart failure, chronic diuretic use, and increase in mortality and hospitalization: an observational study using propensity score methods. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1431–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed A, Ali M, Lefante CM, Mullick MS, Kinney FC. Geriatric heart failure, depression, and nursing home admission: an observational study using propensity score analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:867–75. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000209639.30899.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed A, Perry GJ, Fleg JL, Love TE, Goff DC, Jr, Kitzman DW. Outcomes in ambulatory chronic systolic and diastolic heart failure: a propensity score analysis. Am Heart J. 2006;152:956–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Asso. 1984;79:516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:757–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin DB. Using propensity score to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2001;2:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 18.SPSS. SPSS for Windows, Rel. 14. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murberg TA, Bru E, Svebak S, Tveteras R, Aarsland T. Depressed mood and subjective health symptoms as predictors of mortality in patients with congestive heart failure: a two-years follow-up study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1999;29:311–26. doi: 10.2190/0C1C-A63U-V5XQ-1DAL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaccarino V, Kasl SV, Abramson J, Krumholz HM. Depressive symptoms and risk of functional decline and death in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musselman DL, Evans DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:580–92. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kop WJ, Verdino RJ, Gottdiener JS, O’Leary ST, Bairey Merz CN, Krantz DS. Changes in heart rate and heart rate variability before ambulatory ischemic events(1) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:742–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parissis JT, Adamopoulos S, Rigas A, Kostakis G, Karatzas D, Venetsanou K, Kremastinos DT. Comparison of circulating proinflammatory cytokines and soluble apoptosis mediators in patients with chronic heart failure with versus without symptoms of depression. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1326–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziegelstein RC, Fauerbach JA, Stevens SS, Romanelli J, Richter DP, Bush DE. Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1818–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camacho TC, Roberts RE, Lazarus NB, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD. Physical activity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:220–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, Arons BS, Barlow D, Davidoff F, Endicott J, Froom J, Goldstein M, Gorman JM, Marek RG, Maurer TA, Meyer R, Phillips K, Ross J, Schwenk TL, Sharfstein SS, Thase ME, Wyatt RJ. The National Depressive and Manic–Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA. 1997;277:333–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]