Abstract

Stigmatization represents a chronic negative interaction with the environment that most people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia face on a regular basis. Different types of stigma—public stigma, self-stigma, and label avoidance—may each have detrimental effects. In the present article, the possible consequences of stigma on onset, course, and outcome of schizophrenia are reviewed. Stigmatization may be conceptualized as a modifiable environmental risk factor that exerts its influence along a variety of different pathways, not only after the illness has been formally diagnosed but also before, on the basis of subtle behavioral expressions of schizophrenia liability. Integrating stigma-coping strategies in treatment may represent a cost-effective way to reduce the risk of relapse and poor outcome occasioned by chronic exposure to stigma. In addition, significant gains in quality of life may result if all patients with schizophrenia routinely receive information about stigma and are taught to use simple strategies to increase resilience vis-à-vis adverse, stigmatizing environments.

Keywords: stigmatization, discrimination, schizophrenia, psychosis, environment, affective symptoms

Introduction

Most individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia will be confronted with some form of stigmatization.1,2 Stigmatization refers to a stereotyped set of negative attitudes, incorrect beliefs, and fears about the diagnosis schizophrenia that impact on how this syndrome is actually understood by others. It involves problems of knowledge (ignorance), attitudes (prejudice), and behavior (discrimination) and may be compounded by a scientifically inaccurate emphasis on biogenetic models of illness on the part of professionals.3–6 Different types of stigma—public stigma, self-stigma, and label avoidance7—may have profoundly defeating consequences for the individual with a psychotic disorder.8–11 Ritsher and Phelan12 suggest that the harmful effects of stigma may work through the internal perceptions, beliefs, and emotions of the stigmatized person, even above and beyond the effects of direct discrimination by others. Most of the research in the area of stigma is based on negative reactions faced by people with schizophrenia in studies on public attitudes or equivalent behavioral research. Research exploring the views of those exposed to stigma is less common. Although stigma is typically noted in professional guidelines, possible interventions are not proposed.13 Therefore, in the present article, the consequences of stigma and their potentially negative impact on onset, course, and outcome of schizophrenia are examined not only from a scientific but also from a user perspective.

Genetic Risk, Stigma, and Schizophrenia

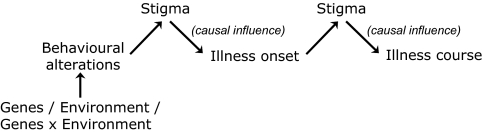

Given the fact that the genetic vulnerability to schizophrenia is likely much more widely distributed than the illness itself, environmental factors impacting on vulnerable individuals may be invoked in order to explain the fact that not all vulnerable people make the transition to psychotic disorder.14 What has received much less attention is the fact that some of these environmental factors may be provoked by the behavioral expression of genetic vulnerability itself, a phenomenon known as gene-environment correlation or rGE.14 In some instances of rGE, the observed environmental risk factor merely represents a genetic epiphenomenon and is of no causal consequence itself. Sometimes, however, the environmental factor in rGE may still be of causal consequence. This latter scenario may be particularly relevant in the prodromal phase of the illness. According to the model described in this article and depicted in figure 1, some of the causal environmental risks for schizophrenia in the realm of social adversity represent structural negative interpersonal interactions in response to the behavioral expression of genetic risk. For example, a person may become stigmatized on the basis of odd speech or paranoid reactions that are the expression of schizophrenia liability. Although in this case stigmatization does not occur on the basis of a formal diagnosis, structural discrimination may nevertheless occur if the behavior is perceived, similar to schizophrenia, as different, out of the ordinary or strange. To the degree that stigma is a form of structural discrimination, the term may be of use in highlighting these early processes associated with schizophrenia liability and form a continuum with the stigma observed after illness onset and its negative consequences on illness course (figure 1). The central theme is that stigmatization/structural discrimination can be perceived as a component of social adversity, which can lead to social defeat and shape specific negative beliefs about the self and about others.15 Presenting the negative interactions induced by liability and illness and their impact on, respectively, onset and course in 1 model may help focus attention on these issues and create more research culminating in risk-reducing strategies.

Fig. 1.

Extended Model of Stigma Taking Into Account Stigma Induced by Expression of Both Illness and Behavioral Alterations Associated With Illness Liability.

Stigma and Onset of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are characterized by alterations in behavioral and cognitive development and, closer to the onset of the first psychotic episode, by an at-risk mental state or “prodromal” phase of illness in which a noticeable change from premorbid functioning occurs.16 Different types of prodrome have been identified, and patients may progress from 1 type to another.17 For example, in 1 type, psychotic symptoms may appear intermittently but briefly. Subsequently, subclinical psychotic symptoms may persist for longer periods, and individuals may at some stage meet International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, criteria for schizotypal personality disorder. Another type consists of neurotic symptoms, which commonly start before positive symptoms; individuals may meet criteria for depression or anxiety disorders.17 The question rises to what degree subtle negative interpersonal interactions induced by the changing behavior of individuals with an at-risk mental state may contribute to the risk of transition to a psychotic disorder. In other words, is it possible that subclinical psychotic experiences or other behavioral expressions of risk provoke stigmatizing reactions that further fuel the underlying psychotic process, increasing the risk for transition to a clinical psychotic episode?

There is face validity to the notion that people displaying behavioral expression of schizophrenia liability, whether it be in the form of a “prodrome,” in the context of “schizotypal” low-grade psychotic experiences or even in the form of subtle developmental behavioral alterations long before illness onset,18 are likely to experience structural discrimination/stigmatization to a degree that it becomes relevant in terms of altering risk for transition to psychotic disorder. Although research is needed to address this question before firm conclusions can be drawn and interventions can be developed or adjusted, there is nevertheless some support for this notion in the literature. For example, Janssen et al19 examined whether perceived discrimination on the basis of skin color or ethnicity, gender, age, appearance, disability, or sexual orientation was prospectively associated with onset of psychotic symptoms. The results indicated that perceived discrimination predicted, in a dose-response fashion, incident delusional ideation. One way of explaining these findings is to hypothesize that subtle changes in the behavior of individuals with early expression of psychosis liability give rise to negative social interactions and structural discrimination that in turn increase the risk for delusional ideation, eg, by facilitating a paranoid attributional style20 and/or by sensitization (and/or increased baseline activity) of the mesolimbic dopamine system.21 A prediction from this model is that in populations who suffer structural discrimination, the proportion of individuals with vulnerability for schizophrenia that actually makes the transition to psychotic disorder should be higher than in nonstigmatized populations. Recent work showing that the observed increased risk for schizophrenia in ethnic minority groups is contingent on the level of associated discrimination these groups are facing is compatible with this notion.22

Stigma and Illness Course

Course and Outcome

Although traditional follow-up studies of cohorts of patients to date have not included measures of stigma as a course modifier, there are nevertheless several reasons to assume that a strong association likely exists. Stigmatization may lead to negative discrimination, which in turn leads to numerous disadvantages in access to care, poor health service, and frequent life events that can damage self-esteem.23 Stigmatization represents a chronic stressor and therefore, given evidence that stress triggers episodes of schizophrenia,24,25 may act as a modifier of illness course. For example, there is some evidence that social stressors such as stigmatizing interactions and victimization can exacerbate symptoms and impact on social functioning.26,27 Furthermore, stigmatization, in the sense of label avoidance, can cause a delay in help- or treatment-seeking behavior. In particular, the threat of social disapproval or diminished self-esteem that accompanies the label may account for underuse of services.28 In addition, prejudice and discrimination related to schizophrenia have been observed to result in poor treatment compliance.29 In a study about internalized stigma, Ritsher and Phelan12 found that alienation predicted depressive symptoms and reduced self-esteem, suggesting that it may be very difficult for individuals to escape, without assistance, a vicious circle of low self-esteem and alienation negatively impacting on each other.12 Awareness of illness may result in better functional outcome, but if awareness is accompanied by acceptance of stigmatizing beliefs, greater social dysfunction, less hope, and lower self-esteem become more likely.30

Psychopathology and Quality of Life

Stigma leads to negative psychological outcomes among the mentally ill, including lowered self-esteem,12,31 diminished self-efficacy,31 and more depressive symptoms.12,31

In a qualitative study by Dinos et al,9 the most common consequences of feelings of stigma revolved around anger, depression, fear, anxiety, feelings of isolation, guilt, embarrassment, and prevention from recovery or avoidance of help seeking. Around 1 in 3 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia has a social anxiety disorder, and it has been suggested that stigma may be closely related to social anxiety in schizophrenia. Thus, presence of social anxiety was predicted by greater experience of shame related to the psychotic diagnosis.32 This finding is highly relevant, given that higher levels of anxiety are associated with more hallucinations, withdrawal, depression, hopelessness, better insight, and poorer function and outcome.33,34 Finally, there is evidence that prejudice and discrimination related to schizophrenia result in an increased probability of misuse of alcohol and drugs.29

Stigmatization can have detrimental consequences for both objective and subjective quality of life (QOL). Attributing one's problems to a mental illness is associated with reduced subjective QOL among persons with schizophrenia, much of which may be mediated by perceived stigma and lower self-esteem.35,36 Persons with mental health problems are often socially rejected, which can have negative consequences for their well-being in general and their self-esteem in particular.37 Anxiety disorders may impose an additional burden to patients with schizophrenia, resulting in further decline in their subjective QOL.38

Interventions for Modifiable Risks?

The data discussed above suggest that stigma may be seen in part as a modifiable risk factor for onset and persistence of psychosis; individual treatments may be developed to promote resilience and help individuals cope better. These interventions may not only be relevant for coping with stigma after illness onset but also before, if individuals show subtle alterations in behavior associated with schizophrenia liability. Although such interventions remain to be developed, the literature suggests a few simple guidelines that may be generally applicable. First, it is useful to differentiate between negative symptoms, depression, anxiety, and the consequences of stigmatization. For example, social isolation can be the result of all the above. Knowledge about (the consequences of) stigmatization is essential in understanding the coping strategies people with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders apply. Conveying such knowledge to professionals during training and to patients and relatives during psychoeducation would be a useful first step.39 Second, several studies have shown that the negative impact of stigma is greater if individuals use avoidant and isolating coping styles in the face of stigma.11,40–44 This suggests that induction of more active coping styles and sharing of experiences, possibly in the context of peer support,45 may be the ingredients of tailored treatments. Another important way of approaching stigma reduction is to offer ways of integration and recovery, eg, through paid employment, which has been observed to reduce stigma.46

References

- 1.Lee S, Chiu MY, Tsang A, Chui H, Kleinman A. Stigmatizing experience and structural discrimination associated with the treatment of schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1685–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickerson FB, Sommerville J, Origoni AE, Ringel NB, Parente F. Experiences of stigma among outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:143–155. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lincoln TM, Arens E, Berger C, Rief W. Can antistigma campaigns be improved? A test of the impact of biogenetic vs psychosocial causal explanations on implicit and explicit attitudes to schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:984–994. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A, Sartorius N. Stigma: ignorance, prejudice or discrimination? Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:192–193. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Causal beliefs and attitudes to people with schizophrenia. Trend analysis based on data from two population surveys in Germany. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:331–334. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulze B. Stigma and mental health professionals: a review of the evidence on an intricate relationship. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:137–155. doi: 10.1080/09540260701278929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corrigan PW, Wassel A. Understanding and influencing the stigma of mental illness. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2008;46:42–48. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20080101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulze B, Angermeyer MC. Subjective experiences of stigma. A focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives and mental health professionals. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:299–312. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinos S, Stevens S, Serfaty M, Weich S, King M. Stigma: the feelings and experiences of 46 people with mental illness. Qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:176–181. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buizza C, Schulze B, Bertocchi E, Rossi G, Ghilardi A, Pioli R. The stigma of schizophrenia from patients’ and relatives’ view: a pilot study in an Italian rehabilitation residential care unit. Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health. 2007;3:23. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-3-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Torres MA, Oraa R, Aristegui M, Fernandez-Rivas A, Guimon J. Stigma and discrimination towards people with schizophrenia and their family members. A qualitative study with focus groups. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:14–23. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2004;129:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for the Treatment of Schizophrenia and Related Disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:1–30. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Os J, Rutten BP, Poulton R. Gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: review of epidemiological findings and future directions. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:1066–1082. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collip D, Myin-Germeys I, Van Os J. Does the concept of “sensitization” provide a plausible mechanism for the putative link between the environment and schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:220–225. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, et al. Psychosis prediction: 12-month follow up of a high-risk (“prodromal”) group. Schizophr Res. 2003;60:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drake RJ, Lewis SW. Treatment of first episode and prodromal signs. Psychiatry. 2005;4:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welham J, Isohanni M, Jones P, McGrath J. The antecedents of schizophrenia: a review of birth cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2008 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn084. Advance Access Published July 24, 2008, doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen I, Hanssen M, Bak M, et al. Discrimination and delusional ideation. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:71–76. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Freeman D, Bebbington PE. A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychol Med. 2001;31:189–195. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E. Hypothesis: social defeat is a risk factor for schizophrenia? Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s9–s12. doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.51.s9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veling W, Selten JP, Susser E, Laan W, Mackenbach JP, Hoek HW. Discrimination and the incidence of psychotic disorders among ethnic minorities in The Netherlands. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:761–768. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sartorius N. Lessons from a 10-year global programme against stigma and discrimination because of an illness. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:383–388. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman RM, Malla AK. Stressful life events and schizophrenia. I: a review of the research. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:161–166. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Winkel R, Stefanis NC, Myin-Germeys I. Psychosocial stress and psychosis. A review of the neurobiological mechanisms and the evidence for gene-stress interaction. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:1095–1105. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanos PT, Moos RH. Determinants of functioning and well-being among individuals with schizophrenia: an integrated model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:58–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, et al. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1627–1632. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59:614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villares CC, Sartorius N. Challenging the stigma of schizophrenia. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2003;25:1–2. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462003000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:192–199. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang LH. Application of mental illness stigma theory to Chinese societies: synthesis and new directions. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:977–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birchwood M, Trower P, Brunet K, Gilbert P, Iqbal Z, Jackson C. Social anxiety and the shame of psychosis: a study in first episode psychosis. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lysaker PH, Salyers MP. Anxiety symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: associations with social function, positive and negative symptoms, hope and trauma history. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:290–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huppert JD, Smith TE. Anxiety and schizophrenia: the interaction of subtypes of anxiety and psychotic symptoms. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:721–731. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900019714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mechanic D, McAlpine D, Rosenfield S, Davis D. Effects of illness attribution and depression on the quality of life among persons with serious mental illness. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:155–164. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunikata H, Mino Y, Nakajima K. Quality of life of schizophrenic patients living in the community: the relationships with personal characteristics, objective indicators and self-esteem. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verhaeghe M, Bracke P, Bruynooghe K. Stigmatization and self-esteem of persons in recovery from mental illness: the role of peer support. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54:206–218. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braga RJ, Mendlowicz MV, Marrocos RP, Figueira IL. Anxiety disorders in outpatients with schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on the subjective quality of life. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin SK, Lukens EP. Effects of psychoeducation for Korean Americans with chronic mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1125–1131. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vauth R, Kleim B, Wirtz M, Corrigan PW. Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lysaker PH, Salyers MP, Tsai J, Spurrier LY, Davis LW. Clinical and psychological correlates of two domains of hopelessness in schizophrenia. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45:911–919. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.07.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooke M, Peters E, Fannon D, et al. Insight, distress and coping styles in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;94:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, Lysaker PH. Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1437–1442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ertugrul A, Ulug B. Perception of stigma among patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davidson L, Chinman M, Sells D, Rowe M. Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:443–450. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perkins DV, Raines JA, Tschopp MK, Warner TC. Gainful employment reduces stigma toward people recovering from schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9158-3. Advance Access Published July 24, 2008, doi:10.1007/310597-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]