Abstract

We examined the possibility of an in-group advantage in detecting intergroup anxiety. Specifically, we videotaped White and Black participants while they engaged in same-race or interrace interactions. Then we asked White and Black observers to view these videotapes (unaware of the racial context) and provide their impressions of participants' anxiety. Two results pointed to an in-group advantage in detecting intergroup anxiety. First, only same-race observers perceived a modulation of participants' anxious behavior as a function of racial context. This held true not only for relatively subjective perceptions of global anxiety, but also for perceptions of single, discrete behaviors tied to anxiety. Second, we found that only same-race observers provided descriptions of anxiety that tracked reliably with participants' cortisol changes during the task. These results suggest that White and Black Americans may have difficulty developing a sense of shared emotional experience.

In March of 2008, in a speech addressing contemporary racial tensions in America, then-Senator Barack Obama suggested that there is a “chasm of misunderstanding that exists between the races.” Could this be true? Is it more difficult for different-race individuals to understand each others' emotions and intentions? Here, we explored whether the ability to detect intergroup anxiety declines when perceptions are made across the racial divide.

Although intergroup interactions are becoming increasingly more common, they remain a source of anxiety for many people. Both majority group members (e.g., Whites in the United States) and minority group members (e.g., Blacks in the United States) show cognitive impairment and negatively-toned emotional and physiological responses during and after intergroup encounters (e.g., Mendes, Major, McCoy, & Blascovich, 2008; Richeson, Trawalter, & Shelton, 2005). For both groups, anxiety stems from a concern about confirming negative stereotypes (e.g., Steele & Aronson, 1995; Vorauer, Main, & O'Connell, 1998). This intergroup anxiety “leaks out” via relatively uncontrollable behaviors (Waxer, 1977), including physical distancing, fidgeting, and vocal tension (Goff, Steele, & Davies, 2008; Shelton, Richeson, & Salvatore, 2005; Weitz, 1972).

Similar to the concept of an in-group advantage in recognizing emotions within cultures (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002), we questioned whether there exists an in-group advantage in detecting intergroup anxiety. Although many studies have examined perceptions of intergroup anxiety (e.g., Mendes et al., 2008; Shelton et al., 2005; Vorauer & Turpie, 2004), and one has examined perceptions of racial bias by same- versus different-race perceivers (Richeson & Shelton, 2005), none, to our knowledge, have directly compared perceptions of intergroup anxiety made by same-race observers to those made by different-race observers. Therefore, this experiment examined the extent to which White and Black observers are differentially attuned to intergroup anxiety among members of their own racial groups.

We asked White and Black participants to complete a stressful task in the presence of a panel of White or Black interviewers, thus manipulating racial context. We videotaped participants' reactions to this situation. Then we asked White and Black observers, who were unaware of the racial context, to view the videotapes and gauge anxiety. We were interested in perceptions of general anxiety and two specific behaviors: vocal tension and reassurance seeking. Vocal tension is an unintentional sign of intergroup anxiety (Weitz, 1972). Reassurance seeking is a relatively uncontrollable activity expressed by those who are anxious and fear negative evaluation (Heerey & Kring, 2007). No work, to our knowledge, has explored the potential for an in-group advantage in the description of single, concrete behaviors such as these, which are ostensibly measured objectively (Burgoon & Baesler, 1991).

We indexed attunement to intergroup anxiety in two ways. First, we questioned whether observers detected a modulation of participants' anxious behavior as a function context (i.e., whether participants were being interviewed by a panel of same-race or different-race individuals). Second, we examined the extent to which observers' ratings predicted participants' objective stress responses, measured with cortisol changes. By examining correspondence between observers' ratings of anxiety and participants' cortisol levels, we could determine the relative accuracy of observers' ratings without concern for participants' attempts to present a more favorable image via self-report.

METHOD

Participants

We recruited Boston-area men and women (N = 193) who self-identified as White/Caucasian or Black/African American, were evenly distributed in gender (54% female, 46% male), and were on average just past young adulthood (age: M = 28.7 years, SD = 10.6 years, range = 18–55 years).

Procedure

All participants were scheduled for afternoon appointments to control for diurnal fluctuations in cortisol. Following initial consent, participants viewed a neutrally-affective video for 30 min before providing a baseline saliva sample. Next, the experimenter informed participants that they would be completing two videotaped tasks before a panel of interviewers: delivering an 8-min speech and performing mental arithmetic (Trier Social Stress Test; Kirschbaum, Pirke, & Hellhammer, 1993). The experimenter then obtained a second informed consent.

For the speech task, participants were instructed to imagine that they were interviewing for a desirable job and to describe why they were well-suited for the job. Depending on condition assignment, participants were evaluated by either two White or two Black interviewers (one male, one female). After meeting the interviewers, participants were given 2 min to prepare the speech alone. At this point the interviewers then reentered the room and the speech task began. After the speech task, participants completed the 5-min mental-arithmetic task1 and then provided the second (reactivity) saliva sample. After 30 min had passed, the participant provided the final (recovery) saliva sample.

Neuroendocrine Measures

We obtained saliva samples using IBL SaliCap sampling devices, which were assayed for salivary-free cortisol using commercial immunoassays kits (IBL, Hamburg, Germany). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variance were less than 10%. For each participant, we calculated two cortisol change scores by subtracting baseline levels from reactivity and recovery samples. We averaged these two values to provide a proxy area under the curve or total amount of cortisol secreted as a consequence of the stressful task.

Observers' Ratings

Self-identified White/Caucasian (n = 11) and Black/African American (n = 8) undergraduate research assistants (observers) were trained to code the videotaped performances of the speech-delivery task. All observers were trained by the same research assistant, who watched 10 pilot participants with the observers and discussed how to code the measures. Once the research assistant was satisfied with the quality of the coding, observers completed the coding independently. Each videotape was coded by at least one White and one Black observer. Observers made a global assessment of participants' anxiety, responding to the item “The subject seemed anxious during the speech” on a scale from −4 (strongly disagree) to +4 (strongly agree). When making ratings of anxiety, observers viewed the videotapes silently. Observers also coded the extent to which participants displayed vocal tension and reassurance seeking throughout the speech delivery on a scale of −3(not at all)to +3(very much). When making ratings of these variables, observers viewed the videotapes with the sound turned on. Low internal consistency precluded the formation of a composite variable.

RESULTS

Data-Analytic Strategy

We tested whether same-race observers would be more likely to detect a situational modulation in anxiety. Therefore, we explored the three-way interaction among the participant's race, interviewers' race, and the match between the observer's and participant's race. For each dependent variable, we conducted a 2 (observer race: same or different from participant) × 2 (participant race) × 2 (interviewers' race) mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA), with repeated measures on the first factor. We decomposed significant three-way interactions by examining the effects of interviewers' race and the match between the observer and the participant separately for White and Black participants. Significant two-way interactions were further examined by conducting simple effects tests within the repeated measures variable—the match or mismatch between participants' and observers' race.

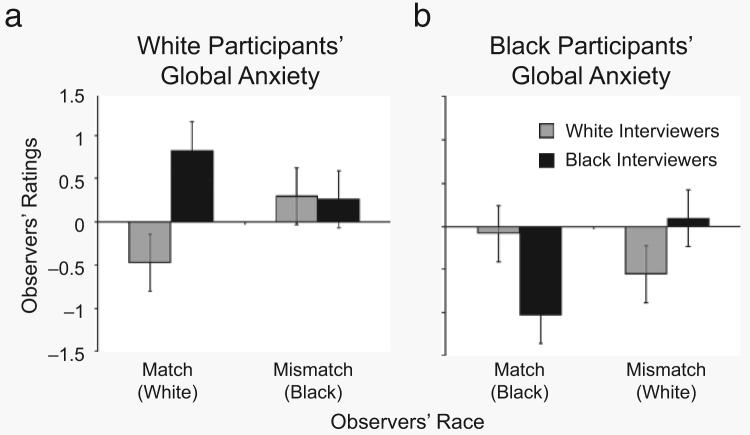

Global Anxiety

Observers' global impressions of anxiety yielded the expected three-way interaction, F(1, 138) = 9.15, prep = .99.2 A significant two-way interaction emerged for ratings of White participants, F(1, 138) = 3.89, prep 5 .88. White observers perceived more anxiety among White participants interacting with Black interviewers (M = 0.85, SEM = 0.30) than with White interviewers (M = −0.47, SEM = 0.36), F(1, 138) = 8.18, prep = .99. However, Black observers did not observe this difference, F(1, 138) < 1.00 (Fig. 1a). The two-way interaction was also significant for ratings of Black participants, F(1, 138) = 5.31, prep = .93. From the perspective of Black observers, Black participants appeared more anxious when their interviewers were White (M = 0.05, SEM = 0.39) than when their interviewers were Black (M = 1.03, SEM = 0.41), F(1, 138) = 5.17, prep = .93. White observers failed to detect this difference, F(1, 138) < 1 (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

White and Black observers' ratings of global anxiety among (a) White participants and (b) Black participants. Separate bars are used to indicate participants who were evaluated by White and Black interviewers. Error bars show standard errors of the means.

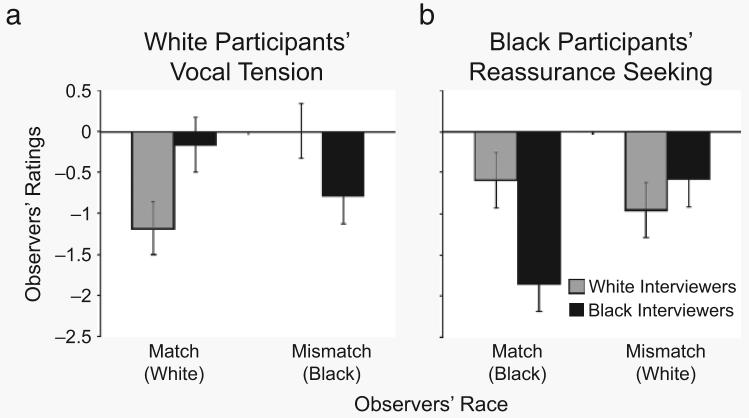

Vocal Tension

Analysis of vocal tension ratings revealed a significant three-way interaction, F(1, 85) = 8.80, prep = .99. When we restricted the analysis to White participants, a significant two-way interaction between observer race and interviewer race emerged, F(1, 85) = 11.07, prep = .99. White observers perceived more vocal tension in White participants who were being evaluated by Black interviewers (M = −0.17, SEM = 0.35) than those being interviewed by White interviewers (M = −1.20, SEM = 0.33), F(1, 85) = 9.71, prep = .99. However, Black observers perceived more vocal tension in White participants who were being evaluated by White interviewers (M = 0.00, SEM = 0.32) than those being interviewed by Black interviewers (M = −0.80, SEM = 0.34), F(1, 85) = 4.52, prep = .89 (Fig. 2a). The two-way interaction was not significant for Black participants, F(1, 85) = 1.14.

Fig. 2.

White and Black observers' ratings of (a) vocal tension among White participants and (b) reassurance seeking among Black participants. Separate bars are used to indicate participants who were evaluated by White and Black interviewers. Error bars show standard errors of the means.

Reassurance Seeking

Ratings of reassurance seeking revealed the expected three-way interaction, F(1, 86) = 6.68, prep = .95. Simple effects tests revealed no significant differences for ratings of White participants. However, for ratings of Black participants, the two-way interaction was significant, F(1, 86) = 5.35, prep = .93. From the perspective of Black observers, Black participants were more likely to seek reassurance when their interviewers were White (M = −0.60, SEM = 0.33) than when their interviewers were Black (M = −1.80, SEM = 0.36), F(1, 86) = 4.58, prep = .91. White observers did not detect this difference, F(1, 86) < 1.00 (Fig. 2b).

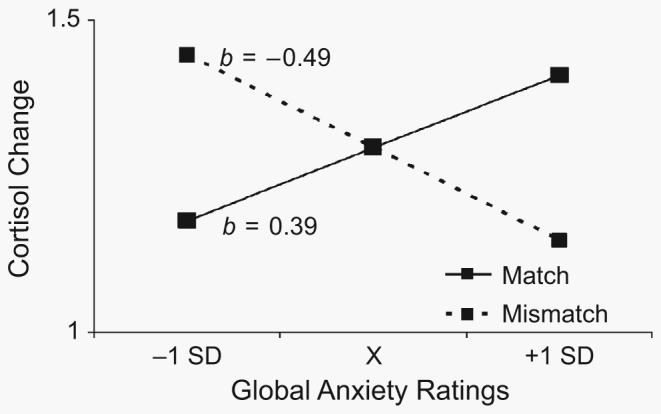

Correspondence of Anxiety Ratings and Neuroendocrine Reactivity

Our results show strong effects for the in-group advantage such that when observers' and participants' race matched, the observers detected modulation of anxiety based on the racial composition of the interview. But to what extent were observers' perceptions accurate? To address this question, we examined the extent to which anxiety ratings predicted participants' changes in cortisol during the course of the experiment. We examined two predictors of participants' average cortisol secretion: global anxiety ratings from race-matched and race-mismatched observers. We also included in this model participants' race and interviewers' race, and then we added the appropriate two- and three-way interactions of these variables in subsequent regression models.

Both sets of anxiety ratings predicted cortisol changes. Ratings made by race-matched observers were in the expected direction, with higher scores predicting greater cortisol increases (b = 0.39, prep = .85). In contrast, when participants' race and observers' race were different, ratings were negatively related to cortisol increases, b = −0.49, prep = .91 (Fig. 3). That is, participant-observer matches resulted in correspondence between anxiety ratings and cortisol responses, but participant-observer mismatches resulted in significant effects in the opposite direction. Because no other main effects or higher-order interactions were significant, we can conclude that the effects were not qualified by the race of the participant or evaluators. The lack of a Participant Race × Interviewer Race interaction suggests that assignment to the same-race versus interrace conditions did not produce different cortisol levels.

Fig. 3.

Average change in cortisol secretion (n/mol) as a function of global anxiety rating (plotted at the mean rating and 1 SD above and below the mean). Results are shown separately for observers whose race matched the participant's race and for observers whose race mismatched the participant's race.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed an in-group advantage in recognizing intergroup anxiety. Race-matched observers—who were not aware of the racial context of the interviews—detected an increase in anxiety during intergroup encounters; however, race-mismatched observers were insensitive to this distinction. Race-matched observers appeared to draw upon subtle nonverbal indicators of intergroup anxiety that were undetectable to race-mismatched observers. Moreover, only race-matched observers were sensitive to cortisol reactivity, an internally-generated response to stress.

These findings are consistent with the broader notion that emotion recognition is diminished when perceivers are asked to identify emotions expressed by members of a different cultural group (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002). The in-group advantage has been attributed to nonverbal “accents,” subtle differences in the appearance of emotional expressions of emotion across cultures (Marsh, Elfenbein, & Ambady, 2003). Although the general language of emotion expression may be universal, members of a single cultural group appear to develop a defining style not easily interpreted by out-group members.

Examination of vocal tension ratings provides support for this explanation. White observers detected an increase in vocal tension when White participants were faced with an interracial encounter, and Black observers sensed the opposite pattern. This is interesting because vocal tension may be an especially diagnostic indicator of Whites' intergroup anxiety. The voice is a highly “leaky” channel of communication in that it readily transmits a signal that the expresser would prefer to conceal (Ekman & Friesen, 1969), and vocal negativity has been identified as a sign of Whites' discomfort during interracial interactions (Weitz, 1972). Together with more controllable signs of racial tolerance (e.g., increased smiling to Black interaction partners), vocal tension may constitute a pattern of “repressed affect,” or tension that one would prefer to disguise as positivity (Shelton, Richeson, & Vorauer, 2006; Weitz, 1972). Here, we demonstrate that only White observers detected the genuine sign of discomfort. Perhaps Black observers took controllable positive behaviors at face value and perceived more positivity— and therefore less vocal tension—among Whites who were being interviewed by Blacks (e.g., Shelton et al., 2006).

Ratings of reassurance seeking resulted in a different pattern: Black observers detected an increase in reassurance seeking among Black participants paired with White interviewers, but White observers failed to make such a distinction. Reassurance seeking is a compulsive “checking” behavior designed to forestall the occurrence of a feared outcome, such as a negative evaluation (Heerey & Kring, 2007). Although both Whites and Blacks often enter intergroup encounters fearful of confirming negative stereotypes, the stereotype they fear confirming is race-specific: Whereas Whites are concerned about appearing prejudiced and unfair (Vorauer et al., 1998), Blacks are anxious about appearing unintelligent and incompetent (e.g., Aronson, 2002). Because the stereotypes are different, the expressions of intergroup anxiety may be different, resulting in greater vocal tension for White participants who feared appearing prejudiced and greater reassurance seeking for Black participants who feared appearing unintelligent and incompetent. The current study suggests that only in-group observers are sensitive to these manifestations.

In sum, this work adds to a growing body of research addressing the emotional, rather than cognitive, side of intergroup perceptions. Past work has demonstrated that people are reluctant to attribute to out-group members a full range of emotional experiences, with harmful consequences for helping and empathy (e.g., Cuddy, Rock, & Norton, 2007). Similarly, relative insensitivity to the emotional states of out-group members may make it difficult to develop a sense of shared emotional experience (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson, 1994). We suggest that future work should investigate the extent to which sustained and meaningful interracial contact, which has the potential to reduce racial prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006), contributes to a reduction in the emotion recognition gap.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO1 HL079383 to W.B.M. and by a National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Advanced Rehabilitation Research Training Grant H133P050001.

Footnotes

We do not present data on nonverbal behavior during the mental-arithmetic portion of the procedure because individuals often produce highly constrained behavior during this task.

Reductions in sample size resulted from a video malfunction, which reduced the sample size available to code.

REFERENCES

- Aronson J. Stereotype threat: Contending and coping with unnerving expectations. In: Aronson J, editor. Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education. Academic; Oxford, England: 2002. pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon JK, Baesler EJ. Choosing between micro and macro nonverbal measurement: Application to selected vocalic and kinesic indices. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 1991;15:57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Rock MS, Norton MI. Aid in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: Inferences of secondary emotions and intergroup helping. Group Relations and Intergroup Processes. 2007;10:107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV. The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding. Semiotica. 1969;1:49–98. [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein HA, Ambady N. On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:203–235. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff PA, Steele CM, Davies PG. The space between us: Stereotype threat and distance in interracial contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:91–107. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL. Emotional contagion. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Heerey EA, Kring AM. Interpersonal consequences of social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:125–134. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. The “Trier Social Stress Test”: A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Elfenbein HA, Ambady N. Nonverbal “accents”: Cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. Psychological Science. 2003;14:373–376. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.24461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes WB, Major B, McCoy S, Blascovich J. How attributional ambiguity shapes physiological and emotional responses to social rejection and acceptance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:278–291. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richeson JA, Shelton JN. Brief report: Thin slices of racial bias. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2005;29:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Richeson JA, Trawalter S, Shelton JN. African Americans' implicit racial attitudes and the depletion of executive function after interracial interactions. Social Cognition. 2005;23:336–352. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Richeson JA, Salvatore J. Expecting to be the target of prejudice: Implications for interethnic interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:1189–1202. doi: 10.1177/0146167205274894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Richeson JA, Vorauer JD. Threatened identities and interethnic interactions. European Review of Social Psychology. 2006;17:321–358. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorauer JD, Main KJ, O'Connell GB. How do individuals expect to be viewed by members of lower status groups? Content and implications of meta-stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:917–937. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.4.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorauer JD, Turpie CA. Disruptive effects of vigilance on dominant group members' treatment of out-group members: Choking versus shining under pressure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:384–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxer PH. Nonverbal cues for anxiety: An examination of emotional leakage. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1977;86:306–314. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.86.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitz S. Attitude, voice, and behavior: A repressed affect model of interracial interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1972;24:14–21. doi: 10.1037/h0033383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]