Abstract

Background

This study examined the effect of fathers’ alcoholism and associated risk factors on toddler compliance with parental directives at 18 and 24 months of age.

Methods

Participants were 215 families with 12-month-old children, recruited through birth records, who completed assessments of parental substance use, family functioning, and parent-child interactions at 12, 18, and 24 months of child age. Of these families, 96 were in the control group, 89 families were in the father-alcoholic-only group, and 30 families were in the group with two alcohol-problem parents. Child compliance with parents during cleanup situations after free play was measured at 18 and 24 months. The focus of this paper is on four measures of compliance: committed compliance, passive noncompliance, overt resistance, and defiance.

Results

Sons of alcohol-problem parents exhibited higher rates of noncompliance compared with sons of nonalcoholic parents. Sons in the two-alcohol-problem parent group seemed to be following a trajectory toward increasing rates of noncompliance. Daughters in the two-alcohol-problem parent group followed an opposite pattern. Other risk factors associated with parental alcohol problems also predicted compliance, but in unexpected ways.

Conclusions

Results indicate that early risk for behavioral undercontrol is present in the toddler period among sons of alcoholic fathers, but not among daughters.

Keywords: Alcoholism, Child Behavior, Psychopathology, Parenting

Parental dysfunction such as alcoholism often serves as a marker variable for a number of other risks associated with alcoholism, such as other psychopathologies (e.g., depression, antisociality), family conflict, problematic infant temperament, and problematic parenting behavior during parent-infant interactions (Eiden et al., 1999; Eiden and Leonard, 1996, 2000; Fitzgerald et al., 1993; Jacob et al., 1991; Jansen et al., 1995; Wong et al., 1999). Taken together, these parental and family variables have a significant influence on child functioning. As early as preschool age, children of alcoholic fathers, especially boys, have been shown to display increased levels of externalizing behavior problems compared with children of nonalcoholic fathers (Puttler et al., 1998). Indeed, it has been hypothesized that one pathway to the greater risk for alcohol problems among children of alcoholics is through the likelihood of early conduct problems among these children leading to antisocial behavior, which in turn is associated with greater substance abuse. Empirical support for this hypothesis has been established in later ages for boys of alcoholic fathers (see Zucker et al., 1995). However, the early antecedents of this pathway have not been investigated to date. Moreover, not all children with alcoholic fathers display a trajectory toward maladaptation. There is a large degree of heterogeneity in outcomes among children of alcoholics. The role of other risk and protective factors in moderating regulatory problems among children of alcoholics is an important area of investigation, because it has direct implications for potential interventions with these high-risk children.

One purpose of this study was to examine the effect of fathers’ alcoholism and associated risk factors on child compliance with parental rules. Child compliance with parental rules is viewed as the first step in the gradual developmental shift from external to internal control of behavior. In this view, compliance is important as a precursor to conscience development (Kochanska et al., 1998). Researchers have established that compliance with rules of conduct emerges during the second year of life (Smetana et al., 2000). The construct of compliance has also been demonstrated as being somewhat heterogenous, with committed compliance being a predictor and an early form of internalization of rules of conduct (Kochanska and Aksan, 1995; Kochanska et al., 1995, 1998). Kochanska and her colleagues have defined committed compliance as reflecting wholehearted engagement with parental agenda and following of parental directives in an enthusiastic, self-regulated, and proactive fashion without immediate parental control (Kochanska et al., 1995, 1998). Various degrees of noncompliance have also been established, with passive noncompliance (mostly ignoring parental control) being most common in the second year of life and being negatively associated with later internalization of rules of conduct. Other forms of noncompliance have also been investigated, such as overt resistance and defiance of parental requests, although given their relatively lower occurrence during standard observational paradigms, not much is known about their precursors or developmental consequences. However, developmental shifts have been noted in all forms of compliance and noncompliance, with increases in committed compliance and general decreases in noncompliance with age, starting in the second year of life.

Theoretically, two major sources of influence on compliance have been suggested: child temperament and parenting behavior. In the domain of child temperament, although specific dimensions of temperament (such as fearfulness) have been implicated (Kochanska, 1995), a generally problematic temperament may be of importance in predicting compliance, especially in interaction with parental alcoholism status. Parenting behavior and the quality of parent-child interactions have long been identified as being important for the development of behavioral regulation, with parent-child interactions characterized by high levels of positive affect associated with higher committed compliance (Kochanska, 1997).

Previous studies have suggested that both of these sources of influence—temperament and parenting—are affected by parental alcoholism (Edwards et al., 2001; Eiden and Leonard, 1996; Eiden et al., 1999). Links have been established between parental alcoholism and less optimal parenting behavior. For instance, fathers’ alcoholism has been associated with higher negative affect and lower positive engagement and sensitivity among fathers, whereas maternal alcohol problems have been associated with lower maternal sensitivity (Eiden et al., 1999). The link between fathers’ alcoholism and infant temperament is less clear (see Zucker et al., 1995). However, there is some evidence that children of alcoholic fathers are perceived by their parents as having a more negative temperament (Edwards et al., 2001; Jansen et al., 1995). The extent to which these reflect actual child characteristics or influences of parental psychopathology on perceptions of the child is unclear.

Other family dynamics associated with alcoholism may also play an important role in predicting children’s compliance. Primary among these are parental psychopathology and family aggression. Both parental psychopathology, such as depression and antisocial behavior, and family aggression have been associated with increased rates of behavior problems among children. For instance, mothers of clinic-referred children had higher levels of maternal depression (Griest et al., 1980; Richman, 1979), and maternal depression was associated with higher levels of behavior problems among boys in nonclinical samples (Gross et al., 1995). Maternal depression was also a significant predictor of child behavior problems among children of alcoholics (Fitzgerald et al., 1993). The data regarding the association between parental conflict or aggression and child behavior problems suggest that families with high levels of conflict have children with higher rates of behavior problems (O’Brien and Bahadur, 1998; O’Keefe, 1994). This relationship is stronger among clinic-referred children compared with general population samples and is stronger for girls compared with boys (Emery and O’Leary, 1984; O’Keefe, 1994). Taken together, current theories regarding variables that promote child compliance and available data on the development of behavior regulation among children suggest several sets of variables that may predict the development of compliance in isolation or in interaction with each other. Primary among them are infant temperament, parenting behavior, parental psychopathology, and family aggression. Although it may be of interest to examine the specific risk factors that may exacerbate negative outcomes, in reality, many of these risk factors are nested in families [see Wong et al. (1999) for a discussion]. Thus, in addition to alcoholism per se, these risk factors taken together may have a direct effect on child compliance or may have interactive effects with parental alcohol problems.

The purpose of this study was 2-fold. The first was to examine whether children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fathers exhibited differences in the development of compliance from 18 to 24 months of age. The second was to understand the role of other risk factors in predicting compliance at 24 months of age. We hypothesized that children of alcoholic fathers would be more likely to display lower levels of committed compliance and higher levels of non-compliance with their parents compared with children of nonalcoholic fathers. Given the literature on boys of alcoholic fathers exhibiting higher risk in terms of externalizing behavior problems, we explored the possibility that fathers’ alcoholism and associated risk factors would have different effects on boys compared with girls. We also hypothesized that the combination of fathers’ alcoholism and additional risk factors would increase the risk for child noncompliance at 24 months of age.

METHOD

Participants

The participants were 215 families with 12-month-old infants who volunteered for an ongoing longitudinal study of parenting and infant development. Of these families, 96 were in the control group (both parents light drinking or abstaining). In 89 families, the father was alcoholic and mother was light drinking or abstaining, and in 30 families, the father was alcoholic and the mother was a heavy drinker (on the basis of their scores on alcohol measures at 12, 18, and 24 months, fathers who met the diagnosis of alcoholism at any time point were considered to be in the alcohol group and mothers who met heavy-drinking criteria at any time point were considered to be in the heavy-drinking group). The majority of the mothers in the study were white (93%), approximately 4% were black, and 2% were Hispanic or Native American. Similarly, the majority of fathers were white (89%), a few were black (8%), and 2% were Hispanic or Native American. The majority of the mothers were high school graduates (41%). Some post–high school education was reported by 30% of the mothers, and an additional 28% were college graduates. Among fathers, there was a slightly higher percentage with a high school diploma (46%) or a college degree (32%), but a lower percentage with a post–high school education such as an associate or vocational degree (18%). All of the mothers were cohabiting with the father of the infant in the study. Most of the parents were married and in their first marriage (87%), approximately 11% were never married, and 1% had previously been married. Mothers’ age ranged from 19 to 41 years (mean, 30.7 years; SD, 4.5 years), and fathers’ age ranged from 21 to 58 years (mean, 32.9 years; SD, 5.9 years). Approximately 62% of the mothers and 93% of the fathers were working outside the home at the time of the 12-month assessment, with very similar percentages working at the 18- and 24-month assessments (66 and 64% of mothers at 18 and 24 months; 93% of fathers at both times). There were few group differences associated with these sociodemographic characteristics. Mothers in the father alcoholic/mother heavy-drinking group were less likely to be white (80%) than mothers in the control (95%) or mothers in the father alcoholic/mother heavy-drinking group (94%). Fathers in the two-father-alcoholic groups had similar education levels, but both groups had significantly lower education levels than fathers in the control group [F(2,217) = 7.08, p < 0.01].

Procedure

The names and addresses of participating families were obtained from the New York State birth records for Erie County and were preselected for normal gestational age, birth weight, and maternal age between 18 and 40 years. Families were sent a letter describing a study of parenting and infant development and were invited to send in a reply form requesting further information and indicating interest. Parents who indicated an interest in the study were screened by telephone with regard to sociode-mographics and further eligibility criteria. Initial inclusion criteria consisted of the parents’ cohabiting since the infant’s birth and the target infant’s being the youngest child in the family; in addition, the mother was not pregnant at recruitment, there were no mother-infant separations for more than a week, the parents were the primary caregivers, and the infant did not have any major medical problems. These criteria were important to control because each of these has the potential to markedly alter parent-infant interactions. Additional inclusion criteria were used to minimize the possibility that any observed infant behaviors could be the result of prenatal exposure to drugs or heavy alcohol use. These additional criteria were as follows: mothers did not use drugs during pregnancy or the past year except for mild marijuana use (no more than twice during pregnancy), mothers’ average daily ethanol consumption was 15 ml or less (one drink a day), and mothers did not engage in binge drinking (five or more drinks per occasion) during pregnancy. During the phone screen, maternal reports of fathers’ drinking as indicated by the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria for alcoholism (RDC; Andreasen et al., 1986) were obtained, in addition to maternal reports of her own drinking. After this maternal phone screen, fathers were screened with regard to their alcohol use, problems, and treatment.

Families who met the basic inclusion criteria were provisionally assigned to one of three groups on the basis of parental screens (control, father alcoholic, both parents with alcohol problems), with final group status assigned on the basis of both the phone screen and questionnaires administered after the family began the study. Mothers in the control group scored below 3 on an alcohol screening measure [tolerance, worried, eye opener, amnesia, cutdown (TWEAK); Chan et al., 1993], were not heavy drinking (average daily ethanol consumption <1.00 ounces or 30 ml), did not acknowledge binge drinking, and did not meet DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence. Fathers in the control group did not meet RDC criteria for alcoholism according to maternal report, did not acknowledge having a problem with alcohol, had never been in treatment, and had alcohol-related problems in fewer than two areas in the past year and three areas in his lifetime (according to responses on a screening interview based on the University of Michigan Composite Diagnostic Index, UM-CIDI; Anthony et al., 1994). The father-alcoholic group consisted of two subgroups: one with partners who had low alcohol problems and the other with partners who had high alcohol problems. A family could be classified in the father-alcoholic group by meeting any one of the following three criteria: (1) the father met RDC criteria for alcoholism according to maternal report; (2) he acknowledged having a problem with alcohol or having been in treatment for alcoholism, was currently drinking, and had at least one alcohol-related problem in the past year; or (3) he indicated having alcohol-related problems in three or more areas in the past year or met DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence in the past year. A mother was considered to have alcohol problems if she met any of the following criteria: (1) TWEAK score of three or higher (Chan et al., 1993); (2) average daily ethanol consumption of 1.00 ounces (30 ml) or higher; (3) she acknowledged drinking five or more drinks per occasion at least once a month; or (4) she met DSM-IV diagnosis for abuse or dependence. Control families were matched to the two other groups with respect to race/ethnicity, maternal education, child sex, parity, and marital status.

Families were asked to visit the Institute at five different infant ages (12, 18, 24, and 36 months and upon entry into kindergarten), with three visits at each age. Extensive observational assessments with both parents were conducted at each age. The primary focus of the 12- and 18-month visits was on parent-infant interactions and attachment. The major focus of the 24- and 36-month visits was on parenting and toddler self-regulation (behavior problems, empathy, compliance, and internalization of parental rules). The major focus of the 60-month visits was on parenting, self-regulation, school adjustment, and peer interactions. Assessments of cognitive and motor development were also conducted at each age. Two weeks before each visit, parents were sent a packet of questionnaires, one for each parent. Both parents were asked to complete the questionnaires independently and return them at the first visit. Families were paid for participation. Child compliance during a cleanup situation (after free-play) was conducted at 18 and 24 months and is the outcome measure of interest in this article.

Measures

Parental Alcohol Use

Although parental alcohol abuse and dependence problems were partially assessed from the screening interview, self-report versions with more detailed questions were used to enhance the alcohol data and check for consistent reporting. A self-report instrument based on the UM-CIDI (Anthony et al., 1994; Kessler et al., 1994) interview was used to assess alcohol abuse and dependence. Several questions of the instrument were reworded to inquire as to “how many times” a problem had been experienced, as opposed to whether it happened “very often.” For questions reworded in this way, subjects had to endorse three or more problems in the past year for the item to be counted in the diagnosis. DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence diagnoses for current alcohol problems (in the past year) were used to assign final diagnostic group status. This instrument was also used to derive continuous measures of the number of parental alcohol-related symptoms in the past year.

A quantity-frequency measure of alcohol use adapted from Cahalan et al. (1969) was used to obtain a measure of average daily ethanol intake for both parents. Finally, a measure indicating severity of heavy drinking was computed. This five-item measure assessed the frequency of drinking six or more drinks, getting drunk, blacking out, passing out, and getting sick. Because of different variances, these items were standardized before summing. The internal reliability of this measure was excellent (α = 0.85).

All of the alcohol measures were highly skewed and were transformed by using square-root transformations. The resulting alcohol variables for each parent were strongly correlated with each other and were highly correlated across time (12, 18, and 24 months). Factor analyses were conducted to create composite factors with the three measures of alcohol problems at each time point for each parent: number of last-year abuse or dependence problems, severity of heavy drinking, and average daily ethanol intake. The factor analyses yielded a single factor for each parent, with high communality values ranging from 0.82 to 0.91 for fathers and 0.71 to 0.87 for mothers. Two composite scores were created, representing paternal and maternal alcohol problems for each time point. The stability of these composite scores across 12, 18, and 24 months was quite high, ranging from r = 0.64 for 12- to 24-month stability in maternal alcohol problems to r = 0.84 for 18- to 24-month stability for both maternal and paternal alcohol problems. Thus, the composite alcohol problem score for each parent was averaged to indicate alcohol problem severity across the first 24 months of the child’s life. The internal consistencies of these two composite scores reflecting severity of alcohol problems for each parent were α = 0.90 for fathers and α = 0.88 for mothers.

Parents’ Antisocial Behavior

A modified version of the Antisocial Behavior Checklist (Zucker and Noll, unpublished data, 1980) was used in this study. Because of concerns about causing family conflict as a result of parents’ reading each others responses, items related to sexual antisociality and those with low population base rates (Zucker, personal communication, 1995) were dropped. This resulted in a 28-item measure of antisocial behavior. Parents were asked to rate their frequency of participation in a variety of aggressive and antisocial activities along a four-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often), yielding potential scores from 28 to 112. The measure has been found to discriminate among groups with major histories of antisocial behavior (e.g., prison inmates, individuals with minor offenses in district court, and university students; Zucker and Noll, unpublished data, 1980) and between alcoholic and nonalcoholic adult men (Fitzgerald et al., unpublished data, 1991). Parents’ scores on this measure were also associated with maternal reports of child behavior problems among preschool children of alcoholics (Jansen et al., 1995). The original measure has adequate test-retest reliability (0.91 over 4 weeks) and internal consistency (coefficient α = 0.93). The antisocial behavior scores for both fathers and mothers were skewed and were transformed by using square-root transformations. The internal consistency of the 28-item measure in the current sample was quite high for both parents (α = 0.90 for fathers and 0.82 for mothers). Because the measurement of antisocial behavior was historical, reflecting a lifetime of antisociality, the measure was administered at the 12-month time point only.

Parents’ Depression

Parents’ depression was assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Inventory (Radloff, 1977), a scale designed to measure depressive symptoms in community populations. This scale is a widely used, self-report, four-point Likert-type measure. Parents were asked to report how often they experienced 20 depressive symptoms (e.g., poor appetite, feeling sad, inability to concentrate) during the past week, with responses including rarely or none, some, or a little of the time (1–2 days); occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–4 days); or most or all of the time (5–7 days). The scale has high internal consistency (Radloff, 1977) and strong test-retest reliability (Boyd et al., 1982; Ensel, 1982). In this study, the depression scores for both parents were skewed and were transformed by using square-root transformations. Depression for both parents was measured at 12, 18, and 24 months. The stability of the total depression scores was quite high, ranging from r = 0.57 for 12-to 24-month paternal depression to r = 0.65 for 18- to 24-month paternal and maternal depression. To create a composite score reflecting paternal and maternal depression across the first 24 months of the child’s life, the 12-, 18-, and 24-month depression scores for each parent were composited into single scales reflecting maternal and paternal depression. The internal consistency of this scale for this sample ranged from α = 0.84 for fathers to α = 0.82 for mothers.

Parents’ Aggression

Two measures of verbal and physical aggression were used in this study. Mother and father reports of physical aggression were obtained from a modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979). The items focusing on moderate (e.g., push, grab, or shove) to severe (e.g., hit with a fist) physical aggression, but not the very severe items (e.g., burned or scalded, use of weapons), were used in this study. Parents were asked to report on the frequency of their own and their partner’s aggression toward each other on a seven-item scale. Two composite physical aggression scores, one for each parent, were created by taking the maximum of each parent and the partners’ reports of aggression. The resulting scores were highly skewed and were transformed by using square-root transformations. Verbal aggression was measured by a modified version of the Index of Spouse Abuse scale (Hudson and McIntosh, 1981). Only the verbal aggression items were used from the original scale. Parents were asked to report on the frequency of their partners’ verbal aggression toward them on the resulting 15-item measure along a five-point scale ranging from “never” to “frequently.” A composite verbal aggression measure was created by summing the items and transforming the summed score. To create two single scales reflecting paternal and maternal aggression across the first 24 months of the child’s life, composite scales that consisted of verbal and physical aggression of each parent at 12, 18, and 24 months were created by taking the average across the measures. The internal consistencies of the final composite scales were α = 0.84 for mothers and α = 0.91 for fathers.

Infant Temperament

Mother and father reports of infant temperament were obtained by the Infant Characteristics Questionnaire (Bates et al., 1979). The scale consists of 32 items scored on a seven-point scale. High scores on all the items reflected a more problematic temperament. In previous reports, the Fussy-Difficult factor has been found to have stability from 6 to 24 months (Bates et al., 1979). However, less is known about the stability of the other factors, and the item content of these other factors has been found to vary across time. Because we were interested in creating composite scales reflecting dimensions of temperament that were relatively stable across time and emerged for ratings given by both parents, we performed several exploratory principal-components analyses on the scales. These analyses were performed separately at each age and for each parent. We were looking for factors that were similarly composed over time. By following procedures outlined by other temperament researchers (e.g., Lemery et al., 1999), we systematically varied the number of factors extracted and the method of rotation. We then selected a three-factor solution by examining the eigenvalues and by using the scree test for determining the number of components to retain. This three-factor solution was identified by using varimax rotation. The factors were Fussy-Difficult, Response to Novelty, and Persistence. The Fussy-Difficult scale was similar to the original scale by Bates et al. (1979) and measured the extent to which the parent perceived the infant as being difficult to care for (e.g., how much does your baby cry and fuss in general?). The Response to Novelty scale measured the child’s typical response to novel situations (e.g., how does your baby typically respond to a new person?) and is similar to the fearfulness or distress to novelty dimension identified with other scales of temperament (Goldsmith et al., 1991; Rothbart, 1981). The Persistence scale measures interest in exploration and impulse control. Composite ratings were created for each scale and each parent. The stability ratings for each scale at each time point were moderate, with correlations ranging from 0.50 for Persistence by fathers’ report to 0.68 for Fussy-Difficult by maternal report. All of the scales had high internal consistencies ranging from standardized α = 0.78 for Persistence according to paternal report to α = 0.82 for Fussy-Difficult by maternal report. Because of the possibility that the scales reflected, at least in part, parents’ perceptions of the child as opposed to child’s characteristics, we did not composite maternal and paternal ratings into single scales reflecting the child’s temperament. However, there was moderate association between maternal and paternal ratings, ranging from r = 0.32 for Persistence to r = 0.54 for Response to Novelty.

Parenting Behavior

Parents were asked to interact with their infants as they normally would at home for 10 min in a room filled with toys. These free-play interactions were coded with a collection of global five-point rating scales developed by Clark et al. (unpublished data, 1980), with higher scores indicating more positive affect or behavior. These scales have been found to be applicable for children ranging in age from 2 months to 5 years and have been recently validated with a large, normative sample of mothers and children (Clark, 1999).

All the scale points were clearly defined and seem to be directly related to the underlying construct. Clark (1986) found these scales to differentiate between psychiatrically ill and well mothers in terms of affective involvement, responsivity, and predictability in interactions with children, with psychiatrically ill mothers obtaining lower ratings on all these scales. Also, paternal and maternal alcohol problems have been associated with parenting behavior coded with these scales (Eiden and Leonard, 1996; Eiden et al., 1999). Furthermore, these scales have been found to differentiate more secure from less secure infants and preschoolers (Teti et al., 1991) and to be associated with maternal working models of attachment (by using the Adult Attachment Interview) and child security (Eiden et al., 1995). Three major aspects of parenting behavior were coded by using a collection of 38 scales: negative affect, positive engagement, and sensitivity. Details regarding coding and derivation of these scales have been described previously (Eiden et al., 1999). Parenting behavior across 12, 18, and 24 months was composited for each parent. The resulting six scales had high internal consistencies ranging from 0.89 to 0.91.

Two female coders rated parental behavior. The coding of maternal and paternal behavior was alternated between the two coders so that the coder who coded one parent did not code the other parent. Both coders were trained on the Clark scales by the first author (RDE) and were unaware of group membership and of all other data. The interrater reliability was fairly high, ranging from r = 0.89 to r = 0.95 (Pearson correlations) for each of these six composite scales.

Cumulative Risk Score

Because family and child risk were generally nested within families [see Wong et al. (1999) for a discussion], we created a composite risk score to examine the cumulative effect of risk on compliance and to examine the interactive effects of the severity of parents’ alcohol problems and risk. The risk factors included in this composite score were as follows: paternal and maternal reports on the three temperament subscales; fathers’ depression; mothers’ depression; fathers’ antisocial behavior; mothers’ antisocial behavior; fathers’ and mothers’ negative affect, positive engagement, and sensitivity during play with infant; fathers’ aggression toward mothers; and mothers’ aggression toward fathers. Scores above and below the median were used as the cutoff for risk. For fathers’ depression, total depression scale scores above 6 were assigned to the risk category (45% of the sample). For mothers’ depression, total depression scale scores above 7 were assigned to the risk category (46% of the sample). For fathers’ antisocial behavior, scores above 38 were assigned to the risk category (46% of the sample). For mothers’ antisocial behavior, scores above 35 were assigned to the risk category (48% of the sample). For fathers’ positive engagement during play, scores below 3.86 were assigned to the risk category (49% of the sample). For fathers’ negative affect during play, scores below 4.50 were assigned to the risk category (42% of the sample). For fathers’ sensitivity during play, scores below 3.83 were assigned to the risk category (48% of the sample). For mothers’ positive engagement during play, scores below 4.02 were assigned to the risk category (48% of the sample). For mothers’ negative affect during play, scores below 4.50 were assigned to the risk category (45% of the sample). For mothers’ sensitivity during play, scores below 3.68 were assigned to the risk category (47% of the sample). For fathers’ aggression toward mother, scores above 0.77 were assigned to the risk category (49% of the sample). For mothers’ aggression toward father, scores above 1.39 were assigned to the risk category (50% of the sample). The total risk score was computed by counting the total number of risk categories, with a possible range of scores between 0 and 18. The range of scores in this study was 0 to 17 (mean, 9.39; SD, 3.63).

Child Compliance

Child compliance was assessed during a cleanup procedure after free play according to guidelines developed by Kochanska and Aksan (1995). After the 10-min parent-infant free play, parents were asked to have the child put all the toys away. Parents were given up to 10 min, and the paradigm was finished when the parent communicated that the task was completed or after 10 min. Child compliance during cleanup was coded according to guidelines developed by Kochanska and Aksan (1995). Each 30-sec segment was coded for the predominant quality of child compliance or noncompliance. The coding categories developed by Kochanska and her colleagues consist of five mutually exclusive codes: committed compliance, situational compliance, passive noncompliance, overt resistance, and defiance [see Kochanska et al. (1998) for further details about this coding scheme]. Given that situational compliance was fairly common at both 18 and 24 months and did not predict any later outcome, it was dropped from analyses.

Committed compliance consisted of child behaviors such as enthusiastically picking up toys and putting them in the boxes, spontaneously moving to a new pile of toys to clean up, etc. Passive noncompliance consisted of child behaviors such as ignoring parent, seeming not to hear parent, playing with toys, and taking toys out of the boxes instead of putting them in. Overt resistance reflected an oppositional response to parental requests and consisted of refusals to clean up or negotiations in the absence of anger. Defiance reflected protest or resistance to parental rules accompanied by anger or other negative affect. For instance, trying to leave the room or taking the toys out of the boxes, if accompanied by fussiness or whining, was coded as defiance. Defiance also included temper tantrums, kicking toys, or doing the opposite of what the parent asked. Coders of compliance data were blind to other information about the families and were unaware of group status. Interrater reliability was established on 15% of the tapes and ranged from 0.85 for 18-month committed compliance with mothers to 0.98 for 18-month committed compliance for fathers.

RESULTS

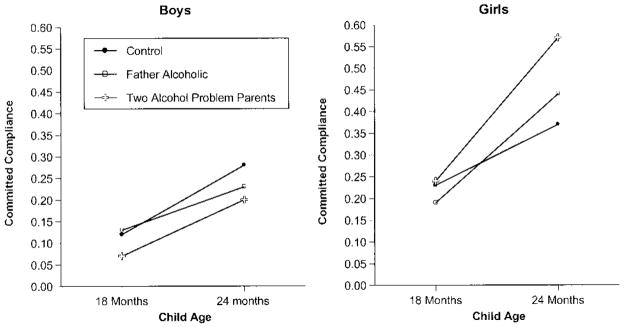

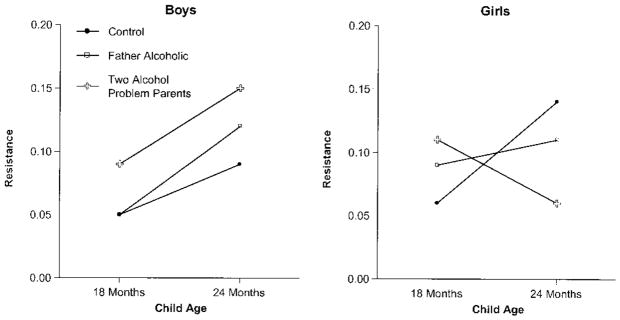

Repeated-measures analysis of variance was conducted with child age and parent (compliance with mother versus father) as the within-subject factors. Child sex and group status (control, father alcoholic, and two alcohol-problem parents) were between-subjects factors. The four compliance measures were used as the dependent variables. This analysis yielded a significant multivariate interaction effect of age, child sex, and group status [F(4,194) = 3.54, p < 0.05]. Univariate analyses indicated significant age, sex, and group status interaction effects for committed compliance [F(1,196) = 2.96, p < 0.05] and for resistance [F(1,196) = 3.56, p < 0.01]. Simple effects analyses indicated that at 18 months, there were sex differences in committed compliance in the control group such that girls exhibited more committed compliance compared with boys, but this sex difference was no longer significant at 24 months. There was no sex difference in committed compliance at 18 months within the two alcoholic groups, but at 24 months, girls exhibited more committed compliance compared with boys in both alcoholic groups. There were no group differences in committed compliance at 18 or 24 months among boys or at 18 months among girls. However, at 24 months, girls in families with two alcohol-problem parents showed more committed compliance compared with girls in the control group (see Fig. 1). There was a marginal difference in committed compliance (p = 0.06) between the two alcohol groups (father only versus both parents with alcohol problems). Simple effects analyses with resistance indicated a marginal group difference at 18 months among boys, with boys in the group with two alcohol-problem parents having higher resistance compared with boys in the other two groups (see Fig. 2). At 24 months, boys in the group with two alcohol-problem parents continued to exhibit significantly higher resistance compared with boys in the control group and marginally higher resistance compared with boys in the alcoholic-father-only group. Among girls, there were no group differences in resistance at 18 months, but at 24 months, girls in the control group had significantly higher levels of resistance compared with girls in the group with two alcohol-problem parents. There were no sex differences in resistance at 18 months. However, at 24 months, within the control group, girls had higher resistance compared with boys, but in the group with two alcohol-problem parents, boys had higher resistance compared with girls. Unlike boys in all three groups and girls in the control group, girls in the two alcoholic groups did not exhibit increases in resistance from 18 to 24 months.

Fig. 1.

Interaction effect of group, child sex, and child age on mean levels of committed compliance with both parents.

Fig. 2.

Interaction effect of group, child sex, and child age on mean levels of resistance with both parents.

The repeated-measures analysis of variance also yielded significant main effects of age, parent, and sex, although these were qualified by the interaction effects noted previously. Committed compliance and resistance increased with age; passive noncompliance and defiance decreased with age. Toddlers exhibited less committed compliance, more passive noncompliance, and more defiance with mothers compared with fathers. Finally, boys exhibited lower committed compliance, higher passive noncompliance, and higher defiance compared with girls.

Parental Discipline

Repeated-measures analysis of variance was conducted with child age and parent (mother versus father) as the within-subjects factors. Child sex and group status (alcoholic versus control) were between-subjects factors. The two levels of parental discipline (gentle guidance and control) were the dependent variables. This analysis yielded significant main effects of child age and sex, but these were qualified by a significant multivariate interaction effect of child age and sex [F(2,198) = 3.49, p < 0.05]. Simple effects analyses indicated that parents used increasing levels of gentle guidance and decreasing levels of control from 18 to 24 months for both boys and girls. There were no sex differences in use of gentle guidance or control at 18 months. However, at 24 months, parents used more gentle guidance and less control with girls compared with boys. There were no significant effects involving group status.

Correlational analyses were used to examine contemporaneous and longitudinal associations between parental behavior during cleanup and child compliance. Among mothers, higher gentle guidance at 18 months was associated with higher committed compliance at both 18 and 24 months (r = 0.42, p < 0.001 and r = 0.17, p < 0.05, respectively), lower passive noncompliance at 18 months (r = −0.19, p < 0.01), and lower defiance at both 18 and 24 months (r = −0.21 and −0.17, and p < 0.01 and 0.05, respectively). Similarly, higher gentle guidance at 24 months was associated with higher committed compliance and lower passive noncompliance, resistance, and defiance at 24 months (r = 0.52, −0.29, −0.23, and −0.30, respectively, p < 0.001). Higher use of control at 18 months was associated with lower committed compliance at 18 and 24 months (r = −0.40, p < 0.001; r = −0.15, p < 0.05, respectively), higher passive noncompliance at 18 months (r = 0.22, p < 0.001), and higher defiance at 18 and 24 months (r = 0.15 and 0.14, respectively; p < 0.05). Similarly, higher use of control at 24 months was associated with lower committed compliance and higher passive noncompliance, resistance, and defiance at 24 months (r = −0.48, p < 0.001; r = 0.30, p < 0.001; r = 0.22, p < 0.01; and r = 0.15, p < 0.05, respectively). The associations were similar for fathers.

Association Between Fathers’ Alcoholism and Other Risk Factors

Multivariate ANOVAs (MANOVAs) were used to examine the association between fathers’ alcoholism and other risk factors, such as parental psychopathology, family aggression, negative infant temperament, and parenting behavior. Given the sex differences and interaction effects involving sex, both group status and child sex were used as the between-subjects factors. Parental depression and antisocial behavior were used as dependent variables in the first MANOVA. This analysis yielded a significant multivariate effect of fathers’ alcoholism on parents’ psychopathology [F(4,211) = 15.42, p < 0.001]. Univariate analyses indicated that alcoholic fathers were more antisocial and depressed compared with those in the control group. Mothers with alcoholic partners were more depressed compared with those in the control group, regardless of their own alcohol-problem status. Mothers with alcohol problems were more antisocial compared with mothers in the other two groups. Light-drinking mothers with alcoholic partners were also more antisocial compared with mothers in the control group (see Table 1). Maternal and paternal aggression toward each other were used as dependent variables in the second MANOVA. This analysis yielded a significant multivariate interaction effect of group and sex on partner aggression [F(2,214) = 6.50, p < 0.01]. Univariate analyses indicated significant interaction effects for both paternal and maternal aggression. Simple effects analyses indicated that there were no differences in parental aggression by child sex within the control and father-alcoholic-only groups. However, within families with two alcohol-problem parents, mothers displayed higher levels of partner aggression among families with girls compared with those with boys (mean, 4.58 and 1.97; and SD, 3.07 and 1.89, respectively). Among families with boys, both parents in the father-alcoholic group displayed higher levels of aggression toward each other compared with nonalcoholic parents (maternal aggression: mean, 2.49 vs. 1.55; SD, 1.97 and 1.69; paternal aggression: mean, 1.61 vs. 1.01; SD, 1.60 and 1.15). There were no group differences in partner aggression between the two alcohol groups. Among families with girls, those with two alcohol-problem parents displayed higher partner aggression compared with families in the other two groups (for maternal aggression: mean, 4.58; SD, 3.07 in the two-alcohol-problem-parent group; mean, 2.24; SD, 1.79 in the father-alcoholic-only group; mean, 1.62; SD, 1.98 in the control group; for paternal aggression: mean, 2.96, 1.45, and 0.97, respectively; SD, 2.64, 1.40, and 1.28, respectively).

Table 1.

Group Differences in Risk Variables

| Group |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

Father alcoholic |

Both parents with alcohol problems |

||||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F value | p value |

| Father | ||||||||

| ASB | 36.02a | 6.47 | 42.55b | 9.19 | 44.61b | 10.29 | 25.19 | 0.00 |

| Depression | 6.04a | 6.09 | 9.06b | 7.26 | 8.68b | 8.15 | 4.62 | 0.01 |

| Aggression toward mother | 0.98a | 1.21 | 1.53b | 1.49 | 2.23c | 2.20 | 8.91 | 0.00 |

| Negative affect during play | 4.45 | 0.43 | 4.36 | 0.44 | 4.37 | 0.32 | 1.18 | NS |

| Positive affect during play | 3.81a | 0.68 | 3.64b | 0.65 | 3.57b | 0.59 | 2.28 | 0.10 |

| Sensitivity during play | 3.89 | 0.64 | 3.86 | 0.60 | 3.78 | 0.59 | 0.36 | NS |

| ICQ—Fussy-Difficult | 2.64a | 0.59 | 2.91b | 0.64 | 2.67a | 0.65 | 4.86 | 0.01 |

| ICQ—Response to Novelty | 2.82 | 0.65 | 3.01 | 0.69 | 2.93 | 0.69 | 1.83 | NS |

| ICQ—Persistence | 4.09 | 0.73 | 4.21 | 0.69 | 3.97 | 0.70 | 1.51 | NS |

| Mother | ||||||||

| ASB | 34.84a | 4.50 | 36.75b | 5.22 | 40.26c | 7.64 | 17.18 | 0.00 |

| Depression | 7.33a | 6.37 | 9.40b | 7.75 | 10.23b | 7.62 | 4.92 | 0.01 |

| Aggression toward father | 1.59a | 1.82 | 2.37b | 1.88 | 3.15c | 2.78 | 8.23 | 0.00 |

| Negative affect during play | 4.41a | 0.47 | 4.48a | 0.41 | 4.20b | 0.67 | 3.75 | 0.025 |

| Positive affect during play | 4.04a | 0.57 | 4.01a | 0.62 | 3.77b | 0.77 | 2.34 | 0.10 |

| Sensitivity during play | 3.84a | 0.61 | 3.97a | 0.46 | 3.59b | 0.77 | 4.87 | 0.009 |

| ICQ—Fussy-Difficult | 2.47 | 0.62 | 2.63 | 0.64 | 2.69 | 0.70 | 2.06 | NS |

| ICQ—Response to Novelty | 2.83 | 0.73 | 2.81 | 0.72 | 2.93 | 0.81 | 0.31 | NS |

| ICQ—Persistence | 4.10a | 0.80 | 4.32b | 0.78 | 4.33b | 0.66 | 2.27 | 0.10 |

| Composite risk score | 8.16a | 0.34 | 10.14b | 0.36 | 10.79b | 0.62 | 10.91 | 0.001 |

Means with different superscripts were significantly different. High scores on negative affect indicate low negative affect.

ASB, Antisocial Behavior; ICQ, Infant Temperament; NS, not significant.

Two MANOVAs were conducted to examine group differences in parenting behavior. For fathers, this analysis did not yield any significant group differences, although there was a marginal effect of sex at the multivariate level [F(3,211) = 2.06, p = 0.10]. Univariate analyses indicated that fathers with daughters displayed lower negative affect, higher positive engagement, and higher sensitivity compared with fathers with sons. The MANOVA with maternal behavior indicated a significant effect of group status [F(3,213) = 3.87, p < 0.05]. Univariate analyses followed by simple contrasts indicated that mothers with alcohol problems displayed higher negative affect, lower positive engagement, and lower sensitivity during free-play interaction compared with mothers in the other two groups (see Table 1). Finally, ANOVA conducted with the composite risk score yielded a significant effect of group status. Simple contrasts indicated that nonalcoholic families had lower risk scores compared with those in the other two groups (see Table 1).

Taken together, alcoholic fathers were more antisocial, more depressed, and more aggressive toward their partners, had lower positive engagement during interactions with their children, and perceived their children to be more fussy and difficult compared with fathers in the control group. Moreover, alcoholic fathers who had partners with alcohol problems were more aggressive toward them compared with alcoholic fathers with light-drinking partners. Light-drinking mothers with alcoholic partners were more antisocial, more depressed, and more aggressive and perceived their infants as being more persistent compared with mothers in the control group. Mothers with alcohol problems were also more antisocial and more aggressive and exhibited higher negative affect, lower positive engagement, and less sensitivity with both boys and girls compared with mothers in the other two groups. Alcoholic families in general had higher levels of cumulative risk compared with nonalcoholic families.

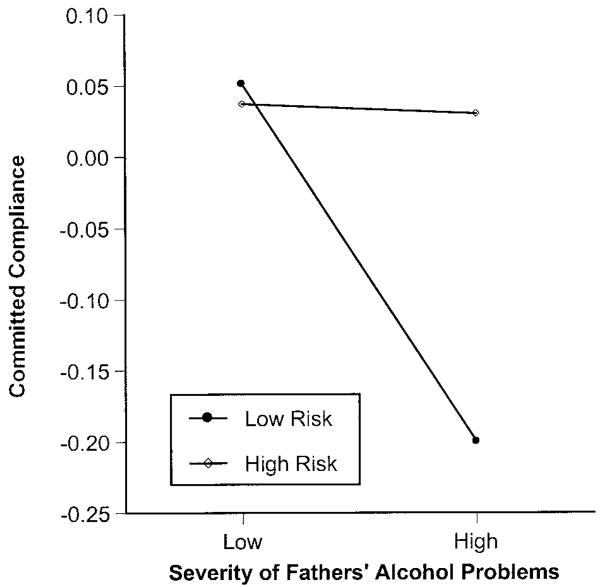

Role of Other Risk Factors in Predicting Compliance at 24 Months

The next step was to examine the role of other risk factors in predicting compliance at 24 months. The composite risk score was used to examine the cumulative effect of risk. Two separate sets of regression analyses were conducted: one predicting compliance among boys and the second predicting compliance among girls. To control for the immediate effects of parental discipline during cleanup, parents’ gentle guidance was entered in the first step, fathers’ severity of alcohol problem score and mothers’ severity of alcohol problem score in the second step, risk score in the third step, and the interaction terms of parental alcohol and risk in the fourth step. These analyses are reported in Tables 2 and 3. As indicated in Table 2, among boys there was a significant interaction effect of fathers’ alcohol and risk on committed compliance with mother. This interaction is depicted in Fig. 3. Among boys with high risk scores, fathers’ alcohol use did not have any effect on committed compliance. However, among boys with low risk scores, higher levels of alcohol problem severity were associated with lower committed compliance.

Table 2.

Regression Analysis: Prediction of Compliance Among Boys

| Standardized |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression |

Coefficients |

|||||||

| Variable | Predictor variables | R2 | R2 Inc | Fch | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 |

| Committed compliance | With mother | |||||||

| Gentle guidance | 0.27 | 0.27 | 41.99*** | 0.52*** | 0.52*** | 0.56*** | 0.53*** | |

| F alcohol problems | 0.29 | 0.02 | 2.36 | −0.12 | −0.16** | −0.23*** | ||

| Risk score | 0.31 | 0.02 | 3.70** | 0.16* | 0.20** | |||

| F risk | 0.34 | 0.03 | 4.32** | 0.18** | ||||

| Passive noncompliant | Gentle guidance | 0.16 | 0.16 | 21.20*** | −0.40*** | −0.40*** | ||

| F alcohol problems | 0.20 | 0.04 | 5.48** | 0.20*** | ||||

| Resistance | Gentle guidance | 0.03 | 0.03 | 2.84 | −0.16** | −0.16** | −0.25*** | |

| F alcohol problems | 0.10 | 0.07 | 4.37** | 0.08 | 0.16** | |||

| M alcohol problems | 0.24** | 0.23** | ||||||

| Risk score | 0.18 | 0.09 | 11.32*** | −0.31*** | ||||

| Defiance | Gentle guidance | 0.06 | 0.06 | 6.53** | −0.24** | −0.23** | ||

| F alcohol problems | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.14 | −0.17* | ||||

| M alcohol problems | 0.16* | |||||||

| Passive noncompliance | With father | |||||||

| Gentle guidance | 0.15 | 0.15 | 19.54 | −0.39*** | −0.39*** | −0.36*** | ||

| F alcohol problems | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.07 | |||

| M alcohol problems | −0.00 | −0.00 | ||||||

| Risk score | 0.18 | 0.03 | 3.82** | 0.18** | ||||

| Resistance | Gentle guidance | 0.05 | 0.05 | 5.84** | −0.23** | −0.23** | −0.25** | |

| F alcohol problems | 0.10 | 0.05 | 5.21** | 0.21** | 0.25** | |||

| Risk score | 0.13 | 0.03 | 3.41** | −0.17** | ||||

M, mother; F, father.

F risk, interactive term of fathers’ alcohol problem severity and risk score.

M risk, interactive term of mothers’ alcohol problem severity and risk score.

Only steps with significant standardized regression coefficients are depicted in the table.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Table 3.

Regression Analysis: Prediction of Compliance Among Girls

| Standardized |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression |

Coefficients |

|||||||

| Committed compliance | Predictor variables with mother | R2 | R2 Inc | Fch | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 |

| Gentle guidance | 0.22 | 0.22 | 30.49** | 0.47** | 0.48** | 0.49** | 0.49** | |

| F alcohol problems | 0.27 | 0.05 | 3.51 | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.10 | ||

| M alcohol problems | 0.23** | 0.21* | 0.19* | |||||

| Risk score | 0.28 | 0.01 | 1.53 | 0.11 | 0.13 | |||

| F risk | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.05 | ||||

| M risk | 0.04 | |||||||

M, mother; F, father.

M risk, interactive term of mothers’ alcohol problem severity and risk score.

F risk, interactive term of fathers’ alcohol problem severity and risk score.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Fig. 3.

Interaction effect of severity of fathers’ alcohol problems and cumulative risk score on committed compliance to maternal rules among boys.

For passive noncompliance with mothers, parental alcohol problems accounted for significant variance even with mothers’ gentle guidance in the equation. Examination of standardized regression coefficients indicated that a more severe paternal alcohol problem was associated with higher passive noncompliance. Addition of risk scores or the interaction scores did not account for significant additional variance. For resistance with mothers, both parental alcohol problems and risk accounted for significant additional variance (see Table 2). Examination of regression coefficients indicated that a higher maternal alcohol problem was associated with higher resistance. Only mothers’ gentle guidance during cleanup predicted defiance with mothers. For compliance with fathers among boys, risk accounted for significant variance in committed compliance such that a higher risk score was associated with higher committed compliance. Fathers’ alcohol problem accounted for additional variance in resistance such that a higher alcohol problem was associated with higher resistance among boys (see Table 2).

Among girls, mothers’ alcohol problem accounted for significant additional variance in committed compliance with mothers. However, the nature of the association was such that a higher maternal alcohol problem was associated with higher committed compliance. For compliance with fathers, only fathers’ gentle guidance was a significant predictor of compliance. Parents’ alcohol problems and risk did not account for additional variance (see Table 3).

Exploratory Analyses: Is it Committed Compliance or Compulsive Compliance?

Given the results that girls in families with two alcohol-problem parents displayed a marked increase in committed compliance from 18 to 24 months and at 24 months displayed higher committed compliance compared with girls in the control group, we conducted several exploratory analyses. Primarily, we explored the possibility that girls with two alcohol-problem parents may be exhibiting high levels of committed compliance due to fear (called compulsive compliance in the child-abuse literature). Consequently, we first examined associations between children’s affect during free-play and structured play and committed compliance during cleanup. Among girls with two alcohol-problem parents, those who displayed higher negative affect (e.g., overt distress, anxiety) during play interactions with their mothers or fathers at 12 months were more likely to display higher rates of committed compliance with both parents at 24 months (r = −0.76, p < 0.01 with mothers and r = −0.36, p < 0.10 with fathers). Results were similar with play interactions at 18 months and committed compliance at 24 months (r = −0.57, p < 0.05 with mothers; r = −0.65, p < 0.01 with fathers). Among girls in the nonalcoholic group, an opposite pattern was obtained. Girls who displayed lower negative affect during play interactions with mothers or fathers at 12 months were more likely to display higher committed compliance with both parents at 24 months (r = 0.25, p < 0.10 with mothers and r = 0.34, p < 0.05 with fathers). At 18 months, there were no associations with child affect during play with mothers and committed compliance, but lower negative affect during play with fathers was associated with higher committed compliance (r = 0.30, p < 0.05). Among girls in the father alcoholic group, only higher negative affect during play interactions with fathers at 18 months was associated with higher committed compliance at 24 months (r = −0.30, p < 0.05). It is important to note that no such associations were obtained for boys. Among boys, negative affect during play interactions was not associated with committed compliance.

Next, we examined associations between parent ratings of child behavior problems (with the Child Behavior Checklist; Achenbach, 1992) at 18 and 24 months and committed compliance at 24 months. Among girls with two alcohol-problem parents, higher scores on the anxious-depressed subscale (by father report) at 18 months was associated with higher committed compliance at 24 months (r = 0.50, p < 0.10). The association with maternal report was in the same direction but not significant due to the small sample size (r = 0.38, p > 0.10). Similarly, among girls with alcoholic fathers and non–alcohol-problem mothers, higher scores on the anxious-depressed subscale by father report at 18 months was associated with higher committed compliance at 24 months (r = 0.31, p < 0.05). There were no associations with maternal reports. In contrast, among girls with nonalcoholic parents, higher scores on anxiety-depression by maternal report at 24 months were associated with lower committed compliance (r = −0.33, p < 0.05). No associations were found with paternal reports or with child behavior at 18 months.

Finally, we coded mutual positive affect during 24-month cleanup for a small subset of girls, all with two alcohol-problem parents and randomly selected for the other two groups (n = 14 in both alcoholic groups; n = 10 in father-alcoholic group; n = 10 in nonalcoholic group). Mutual positive affect was coded according to previous studies (e.g., Kochanska and Murray, 2000). Both parental and child affect were coded every 30 sec by use of a five-point rating scale that ranged from highly positive to highly negative. An interval was considered mutually positive when both the parent and the child displayed positive affect while not displaying negative affect. The total number of mutually positive episodes was divided by the total number of coded episodes. We hypothesized that compulsive compliance was displayed when high levels of committed compliance along with low levels of mutual positive affect occurred. Among girls with two alcohol-problem parents, 46% displayed such a pattern, compared with 27% in the father-alcoholic-only group and 0% in the nonalcoholic group.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies on the development of compliance have noted increases in committed compliance from infancy to the preschool period and decreases in passive noncompliance, resistance, and defiance over time (Kochanska et al., 1995, 1998). Previous studies have also noted sex differences in committed compliance and passive noncompliance, with girls showing higher committed compliance and lower passive noncompliance compared with boys (Kochanska et al., 1995). Our results regarding developmental changes in compliance and sex differences are similar to those of previous studies indicating that committed compliance increases over time and passive noncompliance and defiance decrease over time. However, contrary to previous investigations, there were significant increases in resistance in our sample over time, even within the control group. Moreover, a comparison of the rates of the various forms of compliance within our sample compared with other normative samples indicated that even within the control group, toddlers in our study showed lower rates of committed compliance and higher rates of all forms of noncompliance (see Kochanska et al., 1995, 1998). One explanation for this is that because of group matching on demographics, even our control group represented higher family risk compared with other normative samples.

The results suggest that fathers’ alcoholism is significantly associated with the development of compliance among boys, especially in the presence of maternal alcohol problems. Boys in the group with two alcohol-problem parents exhibited increased levels of overt resistance to parental requests at 18 months and continued to exhibit higher resistance compared with boys with nonalcoholic parents at 24 months. Moreover, higher severity of fathers’ alcohol problems over the first 24 months was associated with higher rates of passive noncompliance during mother-child interactions and higher rates of resistance during father-child interactions among boys. Higher severity of maternal alcohol problems was associated with higher rates of resistance during mother-child interactions among boys. Although some degree of passive noncompliance is fairly normative during the toddler years, these results suggest that sons of alcoholics deviate from sons of nonalcoholics in the degree of noncompliance they exhibit during cleanup interactions with their parents. Previous studies with preschool-age sons of alcoholics have demonstrated that they may be at higher risk for externalizing behavior problems (see Johnson et al., 1991). To the extent that sons of alcoholics continue to deviate from sons of nonalcoholics in the degree of noncompliance exhibited during interactions over time, they may present an increased risk for continued behavioral undercontrol over the preschool years.

Contrary to expectations, girls exhibited an opposite pattern of compliance compared with boys. Daughters of alcoholics, especially those with two alcoholic parents, showed a sharp increase in the level of committed compliance from 18 to 24 months. Indeed, analyses with the severity of alcohol problem measures indicated that higher severity of maternal alcohol problem was associated with higher committed compliance, even after controlling for the immediate effects of maternal behavior during interactions (i.e., maternal gentle guidance). Given that mothers with alcohol problems were more antisocial and aggressive, one possible explanation for this finding is that girls of mothers with alcohol problems were displaying the compulsive compliance discussed in the child-abuse literature (see Crittenden, 1992; Crittenden and DiLalla, 1989; Jacobsen and Miller, 1998). Compulsive compliance has been defined as inhibition of behavior that may be disagreeable to an abusive mother and complying with maternal demands promptly and without need for additional maternal intervention. During cleanup, it is generally difficult to differentiate between compulsive compliance and committed compliance. One possibility was to also code mutual positive affect during cleanup in addition to compliance and maternal discipline. Theoretically, compulsive compliance would occur in the absence of positive affect, whereas committed compliance would be accompanied by mutual positive affect. Indeed, exploratory analyses regarding the possibility of compulsive compliance among girls with two alcohol-problem parents were supportive of the hypothesis that these girls displayed compliance due to fear. The associations between distress during play interactions and higher committed compliance and between higher anxiety and depression on the Child Behavior Checklist and higher committed compliance, and the prevalence of the pattern of high committed compliance in the absence of mutual positive affect, all supported the hypothesis that girls with two alcohol-problem parents displayed compulsive compliance. In the long term, compulsive compliance has been associated with distortions in children’s perceptions of and responses to reality (Crittenden, 1992). Other studies with children of alcoholics have noted that maternal alcohol problems are associated with an increased risk for internalizing behavior problems and depression among girls, but not boys (Christensen and Bilenberg, 2000). Taken together, if indeed daughters of mothers with alcohol problems are displaying higher levels of compliance due to fear, this may be one pathway for maladaptation within this group.

Why is a parental alcohol problem associated with higher compliance in girls but with higher noncompliance in boys? Perhaps the answer lies in the literature examining socialization of emotions and factors that promote internalization of responsibility. The literature on sex differences in the development of conduct problems may also be helpful in this regard (see Zahn-Waxler, 1993). For instance, evidence indicates that caregivers respond in different ways to the same emotion expressed by boys and girls in infancy. Anger expressions by girls are more likely to elicit negative responses from the mother, whereas anger responses by boys are more likely to elicit an empathic response (Malatesta and Haviland, 1982). Moreover, parental characteristics such as maternal negativity and depression have been associated with antisocial behavior among boys (e.g., Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986; Nigg and Hinshaw, 1998). This negative maternal response and differential maternal responding to noncompliance displayed by boys and girls may be heightened among families with aggressive and antisocial mothers.

Furthermore, fathers tend to be more differentiated than mothers in their practices with boys and girls (Lytton and Romney, 1991; Siegal, 1987). Thus, fathers are likely to provide strong signals about appropriate sex role behaviors for boys and girls. Children of antisocial fathers may receive messages about appropriate sex roles that are different and more deviant from children of nonantisocial fathers, hence heightening sex differences and leading to opposite patterns of behavior in their sons versus their daughters.

One of the goals of this study was to investigate the role of other risk factors in predicting outcomes among children of alcoholics. Among boys, increased risk predicted passive noncompliance with fathers, and resistance with both parents. However, the nature of the relationships was contrary to expectations. A higher risk score was associated with lower resistance with both parents among boys. However, as expected, a higher risk score was associated with higher passive noncompliance with fathers, among boys. Perhaps boys from high-risk families were more fearful of exhibiting overt resistance in response to parental requests or demands but were more comfortable ignoring parental requests. We also obtained interactive effects of risk and fathers’ alcohol problem on committed compliance of boys with their mothers. The severity of fathers’ alcohol problems had an effect on committed compliance only when risk was low. If risk was high, fathers’ alcohol problems did not contribute to prediction of compliance. This interaction is identical to that reported in previous studies with outcomes such as externalizing behavior problems, such that fathers’ alcoholism had an effect on child outcomes only when maternal depression was low (Edwards et al., 2001). Thus, risk was associated with compliance among boys in some expected and some unexpected ways.

The lack of findings with defiance is not surprising, given that the base rates of defiance were not high and the distributions of the defiance scores deviated significantly from normality. Overall, the rates of defiance were 10% at 18 months and 5% at 24 months. These rates are similar to those from previous studies (Kochanska et al., 1995, 1998), but given the relatively low base rates and the nature of the distributions, it is not surprising that few relationships emerged with defiance.

There are several limitations in this study. Primary among them are the small sample size of families with two alcohol-problem parents and the fact that maternal alcohol problems can be examined only in the context of paternal alcohol problems in this study. However, it is important to note that in the majority of families with alcohol problems, maternal alcohol problems exist in the context of paternal alcohol problems. In other words, women with alcohol problems are more likely to have partners with alcohol problems than vice versa [see Roberts and Leonard (1997) for further discussion]. Future studies that include samples of mothers with and without alcoholic partners may be able to better answer the question of the role of maternal alcohol problem in the development of compliance. The measurement of compliance included in this study took place in a single cleanup situation and across two time points. As a result, we were unable to examine predictors of changes across time across different situations. As our study progresses, we will be able to add measures of compliance in different contexts as well as at additional time points. On the basis of these results, we will be able to examine whether sons of alcoholic fathers continue to follow a trajectory toward increasing noncompliance across time and also examine early predictors of different trajectories of compliance.

In conclusion, these results suggest that sons of alcohol-problem parents exhibit higher rates of noncompliance compared with sons of nonalcoholic parents, especially in the presence of maternal alcohol problems. Sons in the two-alcohol-problem parent group seem to be following a trajectory toward increasing rates of noncompliance. Daughters in the two-alcohol-problem parent group follow an opposite pattern. Given the current coding of observational data, it is difficult to distinguish between compliance with parental requests because of wholehearted commitment to parental agenda versus compliance due to fear. This is an area for future research with high-risk samples. Fathers’ alcoholism and maternal alcohol problems are associated with multiple risk factors and higher levels of composite risk. Increased family and child risk also play a significant role in predicting compliance, although the nature of these associations is not clear from these results. Future studies with longer follow-up periods will be able to examine developmental trajectories of self-regulation among children of alcoholics, and sex differences in the development of self-regulation as a function of group status, more closely.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank parents and infants who participated in this study and the research staff who were responsible for conducting and coding numerous assessments with these families. Special thanks to Dr. Grazyna Kochanska for her guidance and generous support with materials on measurement and coding of toddler compliance.

Supported by grants from the NIAAA (1RO1 AA 10042-01A1) and the NIDA (1K21DA00231-01A1).

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/2–3 and 1992 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Rice J, Endicott J, Reich T, Coryell W. The family history approach to diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:421–429. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800050019002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;2:244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Freeland CAB, Lounsbury ML. Measurement of infant difficultness. Child Dev. 1979;50:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD, Myers JK. Screening for depression in a community sample: understanding the discrepancies between depression syndrome and diagnostic scales. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:1195–1200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100059010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D, Cisin IH, Crossley HM. Publications Division, Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies. College & University Press; New Haven, CT: 1969. American Drinking Practices: A National Study of Drinking Behavior and Attitudes (Monographs of the Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies No. 6) [Google Scholar]

- Chan AWK, Welte JW, Russell M. Screening for heavy drinking/alcoholism by the TWEAK test. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:463. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen HB, Bilenberg N. Behavioural and emotional problems in children of alcoholic mothers and fathers. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;9:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s007870070046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. Maternal affective disturbances and child competence. Presented at the meetings of the International Conference on Infant Studies; Los Angeles, CA. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. The Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment: a factorial validity study. Educ Psychol Meas. 1999;59:821–846. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM. Quality of attachment in the preschool years. Dev Psychopathol. 1992;4:209–241. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM, DiLalla DL. Compulsive compliance: the development of an inhibitory coping strategy in infancy. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1989;16:585–599. doi: 10.1007/BF00914268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards EP, Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Temperament and behavioral problems among infants in alcoholic families. J Infant Ment Health. 2001;22:374–392. doi: 10.1002/imhj.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Chavez F, Leonard KE. Parent-infant interactions in alcoholic and control families. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:745–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Leonard KE. Paternal alcohol use and the mother-infant relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8:307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Leonard KE. Paternal alcoholism, parental psychopathology, and aggravation with infants. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Teti D, Corns K. Maternal working models of attachment, marital adjustment, and the parent-child relationship. Child Dev. 1995;66:1504–1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, O’Leary KD. Marital discord and child behavior problems in a nonclinic sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1984;12:411–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00910656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensel WM. The role of age in the relationship of gender and marital status to depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982;179:536–543. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Sullivan LA, Ham HP, Zucker RA, Bruckel S, Schneider AM, Noll RB. Predictors of behavior problems in three-year-old sons of alcoholics: early evidence for the onset of risk. Child Dev. 1993;64:110–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Rieser-Danner LA, Briggs S. Evaluating convergent and discriminant validity of temperament questionnaires for preschoolers, toddlers, and infants. Dev Psychol. 1991;27:566–579. [Google Scholar]

- Griest DL, Forehand R, Wells KC, McMahon RJ. An examination of differences between nonclinic and behavior-problem clinic-referred children and their mothers. J Abnorm Psychol. 1980;89:497–500. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.89.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Conrad B, Fogg L, Willis L, Garvey C. A longitudinal study of maternal depression and preschool children’s mental health. Nurs Res. 1995;44:96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson WW, McIntosh SR. The assessment of spouse abuse: two quantifiable dimensions. J Marriage Fam. 1981;43:873–885. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Krahn GL, Leonard KE. Parent-child interactions in families with alcoholic fathers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen T, Miller LJ. Compulsive compliance in a young maltreated child. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:462–463. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen RE, Fitzgerald HE, Ham HP, Zucker RA. Pathways into risk: temperament and behavior problems in three- to five-year-old sons of alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Sher KJ, Rolf JE. Models of vulnerability to psychopathology in children of alcoholics: an overview. Alcohol Health Res World. 1991;15:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wiltchen HE, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Children’s temperament, mother’s discipline, and security of attachment: multiple pathways to emerging internalization. Child Dev. 1995;66:597–615. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: implications for early socialization. Child Dev. 1997;68:94–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N. Mother-child mutually positive affect, the quality of child compliance to requests and prohibitions, and maternal control as correlates of early internalization. Child Dev. 1995;66:236–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Koenig AL. A longitudinal study of the roots of preschoolers’ conscience: committed compliance and emerging internalization. Child Dev. 1995;66:1752–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanksa G, Murray KT. Mother-child mutually responsive orientation and conscience development: from toddler to early school age. Child Dev. 2000;71:417–431. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Tjebkes TL, Forman DR. Children’s emerging regulation of conduct: restraint, compliance, and internalization from infancy to the second year. Child Dev. 1998;69:1378–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemery KS, Goldsmith HH, Klinnert MD, Mrazek DA. Developmental models of infant and childhood temperament. Dev Psychol. 1999;35:189–204. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Family factors as correlates and predictors of juvenile conduct problems and delinquency. In: Torrey M, Morris N, editors. Crime and justice. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1986. pp. 29–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H, Romney DM. Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1991;109:267–296. [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta CZ, Haviland JM. Learning display rules: the socialization of emotion expression in infancy. Child Dev. 1982;53:991–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Hinshaw SP. Parent personality traits and psychopathology associated with antisocial behaviors in childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39:145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien MJ, Bahadur MA. Marital aggression, mother’s problem-solving behavior with children, and children’s emotional and behavioral problems. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1998;17:249–272. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M. Adjustment of children from maritally violent homes. Fam Soc. 1994;75:403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Puttler LI, Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Bingham CR. Behavioral outcomes among children of alcoholics during the early and middle childhood years: familial subtype variations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1962–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Richman N. Behaviour problems in pre-school children: family and social factors. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;131:523–527. doi: 10.1192/bjp.131.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]