Abstract

Plasmodium sporozoites traverse Kupffer cells on their way into the liver. Sporozoite contact does not elicit a respiratory burst in these hepatic macrophages and blocks the formation of reactive oxygen species in response to secondary stimuli via elevation of the intracellular cAMP concentration. Here we show that increasing the cAMP level with dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate (db-cAMP) or isobutylmethylxanthine(IBMX) also modulates cytokine secretion murine Kupffer cells towards an overall anti-inflammatory profile. Stimulation of Plasmodium yoelii sporozoite-exposed Kupffer cells with lipopolysaccharide or IFN-γ reveals down-modulation of TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1, and up-regulation of IL-10. Prerequisite for this shift of the cytokine profile are parasite viability and contact with Kupffer cells, but not invasion. While sporozoite-exposed Kupffer cells become TUNEL-positive and exhibit other signs of apoptotic death such as membrane blebbing, nuclear condensation and fragmentation, sporozoites remain intact and appear to transform to early exoerythrocytic forms in Kupffer cell cultures. Together, the in vitro data indicate that Plasmodium possesses mechanisms to render Kupffer cells insensitive to pro-inflammatory stimuli and eventually eliminates these macrophages by forcing them into programmed cell death.

Keywords: Plasmodium, Malaria, Sporozoite, Liver, Kupffer cell, Macrophage, Cytokine, Chemokine, Apoptosis

1. Introduction

After deposition into the avascular portion of the skin by anopheline mosquitoes (Vanderberg and Frevert, 2004; Amino et al., 2006), malaria sporozoites enter dermal capillaries and travel with the bloodstream to the liver. To reach hepatocytes, their initial site of replication, parasites must first cross the sinusoidal cell layer composed of fenestrated endothelial cells interspersed with Kupffer cells (Frevert, 2004; Frevert et al., 2006). In vitro and in vivo observations indicate that sporozoites actively invade and safely traverse Kupffer cells, exit those towards the space of Disse, and migrate through several hepatocytes before eventually settling down for development to liver stages (or exo-erythrocytic forms; EEF) (Meis et al., 1983; Mota et al., 2001; Frevert et al., 2005; Baer et al., 2007b). A few days later, infected hepatocytes release thousands of merozoites, which enter the bloodstream to invade erythrocytes and thus initiate the blood phase of the malaria infection. Because merozoites, in contrast to sporozoites, are susceptible to phagocytosis by Kupffer cells, they enter the hepatic blood camouflaged as merosomes, large packets of parasites enveloped in host cell membrane (Sturm et al., 2006; Tarun et al., 2006; Baer et al., 2007a).

Kupffer cells represent by far the largest population of tissue macrophages in the body account for approximately 35% of all liver cells (Wake et al., 1989). Aided by their strategic position in the liver sinusoid, these resident phagocytes efficiently clear the bloodstream from plethora of foreign and altered-self substances (Kuiper et al., 1994). Kupffer cells are fully functional professional antigen-presenting cells (APC) (Richman et al., 1979) and, after activation, can secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6 and MCP-1 (Decker, 1990; Kopydlowski et al., 1999). In response to the pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-1ß and TNF-α, activated Kupffer cells also express nitric oxide synthase type II (iNOS) and produce nitric oxide (NO) as well as reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Decker, 1990). On the other hand, Kupffer cells are also key players in a unique immune property of the liver, the induction of portal vein tolerance (Cantor and Dumont, 1967; Crispe et al., 2006). In response to the physiological levels of endotoxin and bacteria entering the portal circulation from the intestines (Jacob et al., 1977), Kupffer cells release anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10 and TGF-β (Knolle and Gerken, 2000). Thus, Kupffer cells occupy a central position in both immune defense against pathogens and maintenance of liver homeostasis.

Accumulating evidence suggests that malaria sporozoites are able to manipulate various Kupffer cell functions to their own advantage. By suppressing MHC class I expression, Plasmodium sporozoites down-modulate the APC function of these macrophages (Steers et al., 2005). Further, sporozoites use the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) to ligate the low-density lipoprotein receptor-like protein (LRP-1) thus inducing a cAMP-dependent signal transduction pathway that suppresses the respiratory burst in Kupffer cells (Usynin et al., 2007). Elevated cAMP levels down-modulate phagocytosis, phagolysosomal fusion, production of ROS, response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and expression of iNOS and cytokines in various types of macrophages and dendritic cells (Lowrie et al., 1979; Rossi et al., 1998; Kambayashi et al., 2001; Aronoff et al., 2005) suggesting that sporozoites use the overall deactivating and anti-inflammatory effect of this second messenger to modulate Kupffer cell function.

Here we report that Plasmodium sporozoites down-regulate the pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1, up-regulate the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, and eventually force Kupffer cells into apoptosis. We propose that by functionally and physically eliminating these hepatic macrophages, Plasmodium generates an overall immunosuppressed microenvironment in the liver that supports parasite survival in hepatocytes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Cell culture media and buffers, media supplements and trypan blue were from Invitrogen/Gibco (Carlsbad, CA). LPS from Escherichia coli 055:B5, mouse IFN-γ, 3-isobutyl-1 methylxanthine (IBMX), dibutyryl cAMP (db-cAMP) were from Sigma (Saint Louis, MI). Collagenase H was from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). FCS was from HyClone (Logan, UT). Cytometric bead array (CBA) mouse inflammation kit was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). APO-BrdU TUNEL Assay Kit, propidium iodide and Hoechst 33342 were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). 8–[4–chlorophenylthio]–2'–O-methyladenosine–3'–5'–cAMP (8–CPT–2'–O-Me-cAMP) and N6-monobutyryladenosine3'–5'-cAMP (6-MB-cAMP) were from BioLog Life Science (Arlington Heights, IL). Monoclonal CI:A3–1 antibody to F4/80 was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). FITC conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-rat IgG were from Boehringer (Indianapolis, IN). Percoll was from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ). Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate LPS detection kit QCL 1000 was from Cambrex (Walkersville, MD).

2.2. Animals and parasites

Swiss Webster and Balb/c mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY) were used according to the recommendations in the guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The cycles of wild-type Plasmodium yoelii strain 17 XNL and P. yoelii expressing green fluorescent protein (PyGFP) (Tarun et al., 2006) were maintained in Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes (Vanderberg and Gwadz, 1980). Sporozoites were isolated from salivary glands after surface decontamination of the mosquitoes with ethanol followed by extensive washing in PBS. To further minimize contaminations, sporozoites were purified by DEAE cellulose chromatography (Mack et al., 1978).

2.3. Determination of salivary gland contamination

To quantify bacterial contamination, serial dilutions of salivary gland (SG) preparations were plated onto Luria-Bertani (LB) medium agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The LPS concentration was determined with a Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate LPS detection kit.

2.4. Kupffer cell isolation and culture

Mouse livers were perfused in situ with calcium-free Hanks' buffered saline followed by digestion with collagenase H (Froh et al., 2002). Kupffer cell purification was by centrifugal elutriation (Knook and Sleyster, 1976) with a Beckman Coulter JE-5.0 elutriation rotor equipped with a Sanderson chamber as described (Usynin et al., 2007). Kupffer cells were collected from 38–68 ml/min at a centrifugation speed of 3,250 g. This protocol yielded cell populations with a reproducible purity and viability of > 95% as determined by trypan blue exclusion and F4/80 surface staining. Cells were cultivated in HEPES buffered RPMI supplemented with 20% FCS and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin G and 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate). After 30–60 min, the medium was replaced to remove unattached cells.

2.5. Kupffer cell treatment

Two day-old Kupffer cell cultures were used. Purified sporozoites were added at a ratio of one or three sporozoites per Kupffer cell. An equivalent amount of uninfected SG extract was added to control wells. To ensure fast sporozoite settlement, cultures were centrifuged at 50 g for 5–10 min. Because the known in vitro stickiness of Plasmodium sporozoites would have required drastic means for quantitative removal, we chose not to disturb the cultures after parasite addition to avoid unspecific Kupffer cell activation. LPS (10–20 ng/ml) or mouse IFN-γ (100–150 U/ml) was added 30 min after addition of the sporozoites. All inhibitors and activators were added 30 min before exposure to the various treatments (see Figure Legends).

2.6. Ex vivo Kupffer cell analysis

To determine the effect of sporozoites on Kupffer cells in vivo, 5–7 × 105 P. yoelii sporozoites or the equivalent amount of control SG extract were injected into the tail vein of Balb/c mice (two per group). Kupffer cells from each group were isolated 18 h later, pooled, allowed to attach to culture dishes for 1 h, washed twice with medium, and stimulated for 6 h with 20 ng/ml LPS. Cell-free supernatants were stored at −80°C until further analysis.

2.7. Cytokine measurement

IL-12p70, TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1 and IL-10 were quantified with a FACS Calibur flow cytometer using the CBA mouse inflammation kit according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.8. TUNEL staining

DNA fragmentation was determined with an APO-BrdU TUNEL (=Terminal deoxynucleotide Transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling) Assay Kit with the following modifications. Cells were washed twice with PBS, air-dried, fixed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, rinsed with PBS and permeabilized for 2 min on ice in 0.1% Triton-X in 0.1% sodium citrate. DNA strand breaks were labeled with the deoxythymidine analog 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate (BrdUTP) using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and detected with an Alexa-Fluor 488-conjugated mouse anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody PRB-1 according to the manufacturer's staining protocol. Cells were counterstained with 1 µg/ml propidium iodide in RNAse solution.

2.9. Double-labeling of intracellular and extracellular sporozoites

Cells were fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and washed twice in PBS. Extracellular sporozoites were labeled with a polyclonal rabbit antiserum against P. yoelii CSP in combination with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG as described (Hügel et al., 1996). After air-drying and membrane permeabilization with 0.01% saponin and 0.5 % BSA in PBS, intracellular parasites were detected with the same antiserum in combination with Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG.

2.10. Immunofluorescence labeling of Kupffer cells

To determine morphological changes in response to parasite exposure, Kupffer cells were fixed after 20 h with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and labeled with monoclonal antibody (mAb) A3–1 against the tissue macrophage-specific surface marker F4/80 followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to FITC. Nuclei were stained with 1 µg/ml Hoechst 33342.

2.11. Microscopy and image analysis

Live and fixed cells were imaged with a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS confocal microscope equipped with a Ludin chamber for control of temperature and CO2 concentration. Image processing was done with Leica LCS software, ImagePro-Plus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) and Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA).

2.12. Statistical analysis

Statistical differences of the cytokine data were analyzed with ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. Statistical differences of all other data were analyzed using the two tailed Student's t-test. Differences of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Protein kinase A (PKA), but not exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC), regulates cytokine production in Kupffer cells

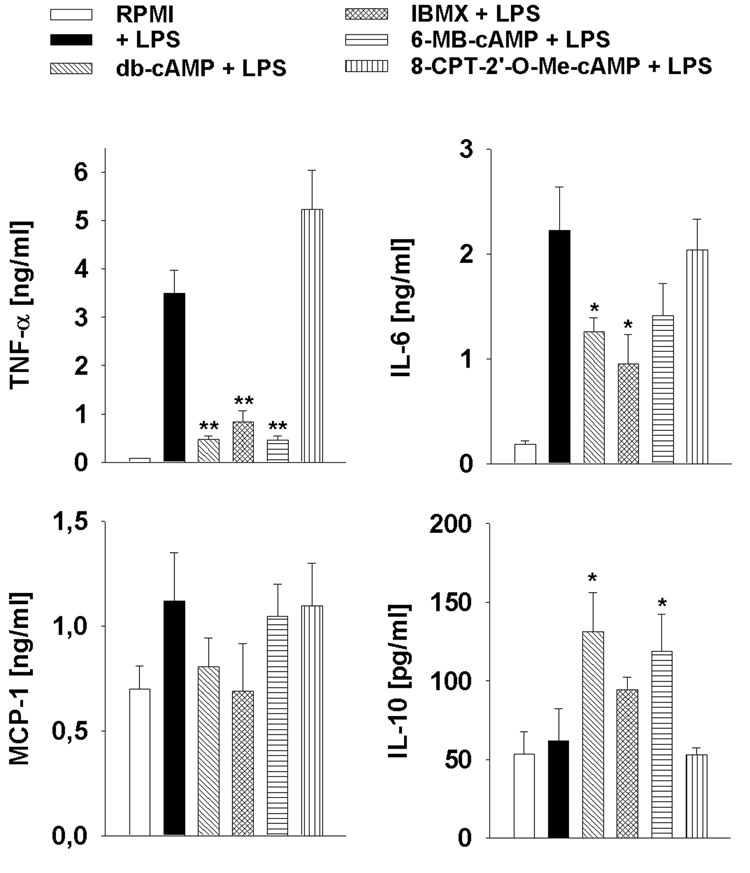

We showed previously that Plasmodium sporozoites block the respiratory burst in Kupffer cells by increasing the intracellular cAMP concentration (Usynin et al., 2007). We found that in contrast to other macrophages (Bengis-Garber and Gruener, 1995), the respiratory burst in Kupffer cells is regulated in a cAMP/EPAC-dependent, but PKA-independent manner. Since cAMP regulates the cytokine network in a variety of cell types including Kupffer cells (Zidek, 1999), we asked if an increase in the cAMP concentration also causes a modulation of the cytokine profile in Kupffer cells. We treated Kupffer cells with the specific cAMP analogs db-cAMP (membrane permeable cAMP analogue), 6-MB-cAMP (selective PKA activator), 8-CPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP (selective EPAC activator), or the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX. When the cells were subsequently stimulated with 20 ng/ml LPS, we found that db-cAMP, IBMX and 6-MB-cAMP all suppressed the production of TNF-α by 76–91% and of IL-6 by 43–71%, whereas the secretion of IL-10 was increased by up to two-fold (Fig. 1). MCP-1 was also suppressed, albeit not significantly. 8-CPT-2'-O-Me-cAMP had no significant effect suggesting that EPAC plays only a minor role in cAMP-mediated cytokine regulation (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Cytokine production by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated Kupffer cells is regulated in a protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent, but exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (EPAC)-independent manner. Kupffer cells were incubated for 30 min with 8-CPT-2’-O-Me-cAMP, 6-MB-cAMP, IBMX, db-cAMP or medium (RPMI) and then stimulated with LPS for another 6 h. Data were expressed as the mean from triplicate wells ± SEM. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01 in relation to controls.

This suggests that cAMP and PKA differentially regulate the cytokine secretion from LPS-stimulated Kupffer cells and that EPAC is not involved.

3.2. Uninfected salivary gland extract stimulates cytokine secretion in Kupffer cells

To examine the effect of parasite encounter on the cytokine profile of Kupffer cells in vitro, we isolated these macrophages from murine livers and co-cultivated them with P. yoelii sporozoites. We chose two different sporozoite-to-Kupffer cell ratios: 1:1, to mimic the natural in vivo situation where one Kupffer cell encounters one parasite, and 3:1, to enhance possible small effects, analogous to work previously done with Toxoplasma (Butcher et al., 2001). Plasmodium sporozoites harvested from anopheline salivary glands are inevitably contaminated with large amounts of mosquito tissue debris, bacteria and other microorganisms (Mack et al., 1978; Usynin et al., 2007). In addition, mosquito saliva comprises a complex molecular cocktail known to stimulate the immune response in the host (Ribeiro, 1987). To evaluate the effect of these mosquito-derived factors, we first exposed Kupffer cells to extracts from uninfected salivary glands. Preliminary data showed that SG preparations from uninfected mosquitoes induced a broad range of cytokines in Kupffer cells, including TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10 (data not shown). To minimize the effect of these mosquito-derived contaminants, all subsequent studies were performed with affinity-purified sporozoites. In our hands, anion exchange chromatography reduced the bacterial contamination in a well reproducible manner about 10-fold from 3.6 ± 3.3 (range from 0.4 – 10, n = 7) to approximately 0.3 ± 0.4 (range from 0.02 to 2, n = 7) bacteria per purified sporozoite. However, 10–30 ng/ml LPS still remained in Kupffer cell supernatants containing our SG preparations. Despite purification by affinity chromatography, control extracts still induced considerable levels of TNF-α, IL-10, IL-6 and MCP-1 compared with medium controls (Fig. 2). Since SG preparations from malaria-infected and uninfected mosquitoes contained the same amount of bacterial contamination (data not shown), we used extracts from the same numbers of uninfected glands, prepared in an identical fashion, as controls.

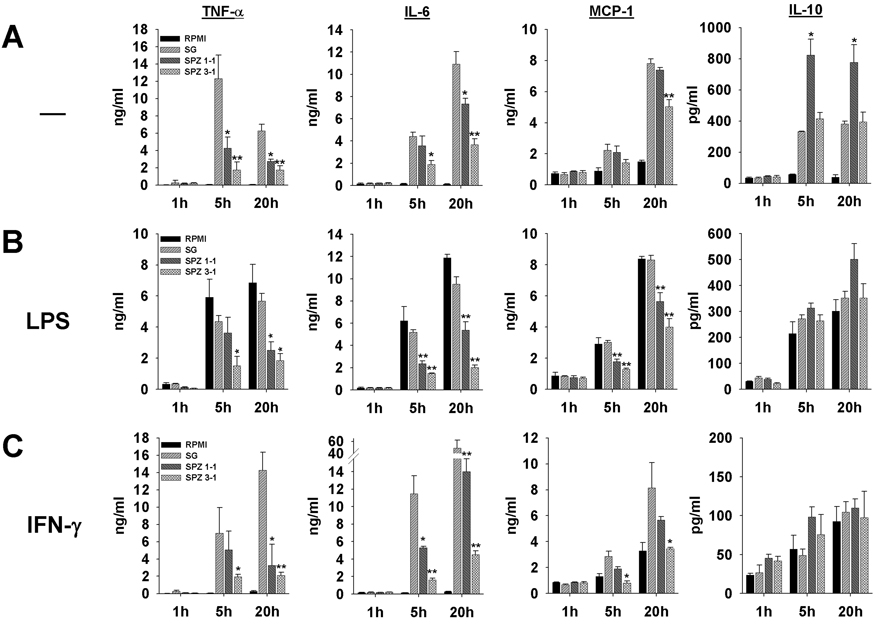

Fig. 2.

Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites suppress secretion of TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1, but not IL-10, in murine Kupffer cells in vitro. A) Cells were incubated with one or three sporozoites per Kupffer cell (SPZ 1:1 or SPZ 3:1) for the indicated periods of time. Control Kupffer cells were treated with uninfected salivary gland extract (SG) or medium alone (CTR). Data were expressed as the median of triplicate wells ± SEM. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01 in relation to SG controls. B) A second stimulus with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (20 ng/ml) was added 30 min after addition of sporozoites or SG extract. C) A second stimulus with IFN-γ (150 U/ml) was added 30 min after addition of sporozoites or SG extract.

3.3. Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites modulate the cytokine secretion profile in Kupffer cells

Since SG preparations induced the production of a wide range of cytokines in Kupffer cells, we asked whether or not sporozoites were able to modify this overall secretion profile. Comparison of sporozoite preparations with uninfected SG extracts revealed that the parasites profoundly suppressed the induction of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 and the chemokine MCP-1, while the levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were increased and unaltered at sporozoite-to-Kupffer cell ratios of 1:1 and 3:1, respectively (Fig. 2A). After 5 and 20 h of co-incubation with one or three sporozoites per Kupffer cell, the parasites suppressed the secretion of TNF-α and IL-6 by 50–80% compared with uninfected SG controls. MCP-1 was slightly down-regulated after 20 h. IL-12p70 secretion from Kupffer cells exposed to sporozoites or SG preparations did not exceed background levels (data not shown). The IL-10 level increased up to two-fold compared with SG controls (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained for Kupffer cells isolated from Swiss Webster (Fig. 2) or Balb/c mice (data not shown).

3.4. The sporozoite-mediated suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines is not abrogated by secondary pro-inflammatory stimuli

Bacterial translocation across the intestinal epithelium into the blood, and influx of endotoxin from the intestines into the portal venous circulation, are natural phenomena to which Kupffer cells are physiologically exposed (Sedman et al., 1994). As stated above, Kupffer cells typically respond to the natural influx of low levels of intestinal endotoxins and bacteria with anti-inflammatory cytokines (Jacob et al., 1977; Knolle and Gerken, 2000). However, Kupffer cells can be activated with high endotoxin concentrations or IFN-γ, and then cause local inflammation and liver injury (Laskin, 1997; Wheeler, 2003). To elucidate whether such pro-inflammatory stimuli can reverse the protective effect exerted by the parasites, we stimulated Kupffer cells 30 min after sporozoite addition with LPS (Fig. 2B) or IFN-γ (Fig. 2C), mediators well-known to induce pro-inflammatory responses in macrophages (Paludan, 2000). Kupffer cells responded to the LPS concentration of 20 ng/ml, which exceeds natural endotoxin levels and is therefore considered pro-inflammatory (Knolle and Gerken, 2000), with secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1 and IL-10 (Fig.2B). Similar to the results shown above, sporozoites suppressed the pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 in a concentration-dependent fashion with a maximum of 50–70% and enhanced the production of IL-10, while control gland extracts had no effect on the response elicited by LPS (Fig. 2B).

IFN-γ, at a concentration of 150 U/ml, did not induce considerable amounts of TNF-α or IL-6, while secretion of MCP-1 and IL-10 increased slightly over time (Fig. 2C). In the presence of IFN-γ, SG controls induced a strong production of TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1, which was suppressed by a maximum of 90% in the presence of sporozoites. On the other hand, both sporozoites and SG controls caused the IL-10 secretion to rise gradually. In contrast to LPS (see above), IFN-γ acted synergistically with the SG contaminants.

We conclude that exposure to SG sporozoites selectively blocks the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from Kupffer cells and enhances the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Remarkably, this modulating effect was not overcome by the secondary pro-inflammatory stimuli exerted by LPS and IFN-γ. This finding is reminiscent of our previous observations on the suppressive effect of sporozoites on the respiratory burst in Kupffer cells normally elicited by secondary stimuli (Usynin et al., 2007). Based on these findings, we propose that P. yoelii sporozoites create an overall anti-inflammatory microenvironment in the vicinity of Kupffer cells they have encountered, which may facilitate the onset of the malaria infection in the liver.

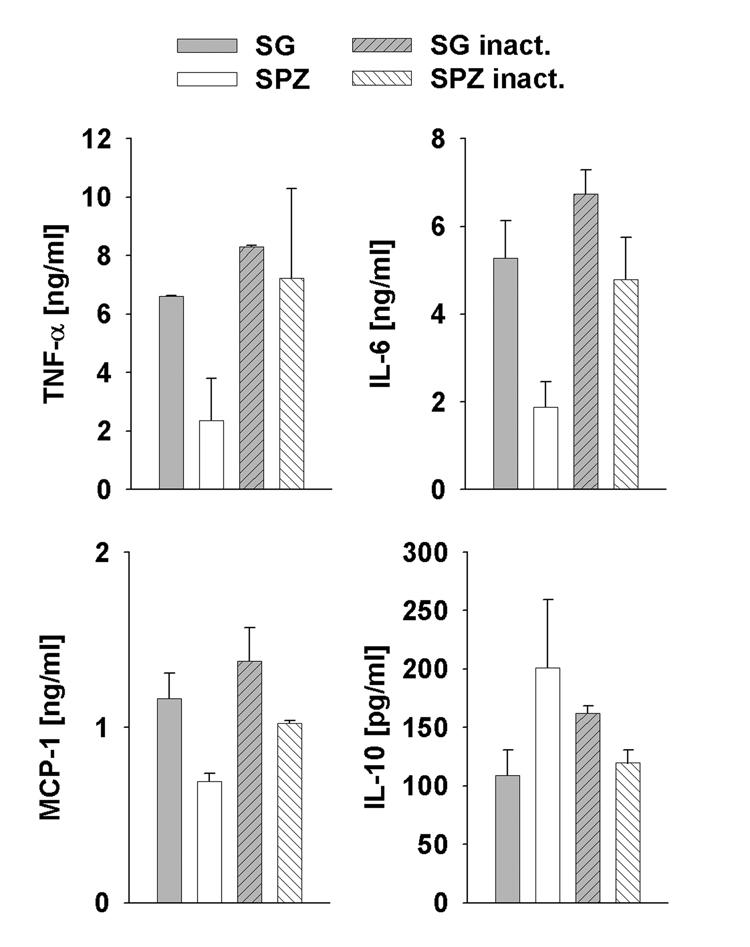

3.5. Sporozoite inactivation abrogates modulation of cytokine secretion

Inactivation of P. yoelii sporozoites by freeze thawing resulted in similar levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 as in the SG controls and thus abrogated the modulating effect of the parasites (Fig. 3). Likewise, sporozoite inactivation caused the IL-10 secretion to decrease to control levels. These data support the notion that sporozoite viability is required for modulation of the cytokine profile in Kupffer cells.

Fig. 3.

Sporozoite inactivation abrogates modulation of cytokine secretion. Cytokine response of Kupffer cell cultures after incubation with viable (SPZ) or inactivated (SPZ inact) sporozoites at a ratio of three sporozoites per Kupffer cell. Control Kupffer cells were treated with non-treated (SG) or inactivated (SG inact) salivary gland (SG) extract. Cytokine levels were analyzed in cell-free supernatants from duplicate wells after 6 h of incubation. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D.

3.6. Plasmodium yoelii infection of mice modulates TNF-α and IL-10 secretion from Kupffer cells

To determine the effect of Plasmodium sporozoites on the cytokine profile of Kupffer cells in vivo, we inoculated mice i.v. with 5–7×105 P. yoelii sporozoites or the equivalent amount of uninfected SG extract. Eighteen hours later, Kupffer cells were purified, cultivated and stimulated for 6 h with 20 ng/ml LPS. Data from three independent experiments show that Kupffer cells from sporozoite-infected mice responded with a 37.2% lower TNF-α secretion than those from sham-infected animals, while secretion of IL-10 was increased by 59% in infected mice compared with the controls (data not shown). This trend was further emphasized by the TNF-α:IL-10 ratio, which was strongly decreased compared with the sham-infected controls. Thus, while only a small proportion of the overall Kupffer cell population could have encountered a parasite under these experimental conditions, priming of these few Kupffer cells nevertheless caused a clearly detectable, although not significant, response to subsequent LPS stimulation, namely suppression of TNF-α and up-regulation of IL-10. This finding further supports the notion that P. yoelii infection induces an overall anti-inflammatory microenvironment in the liver.

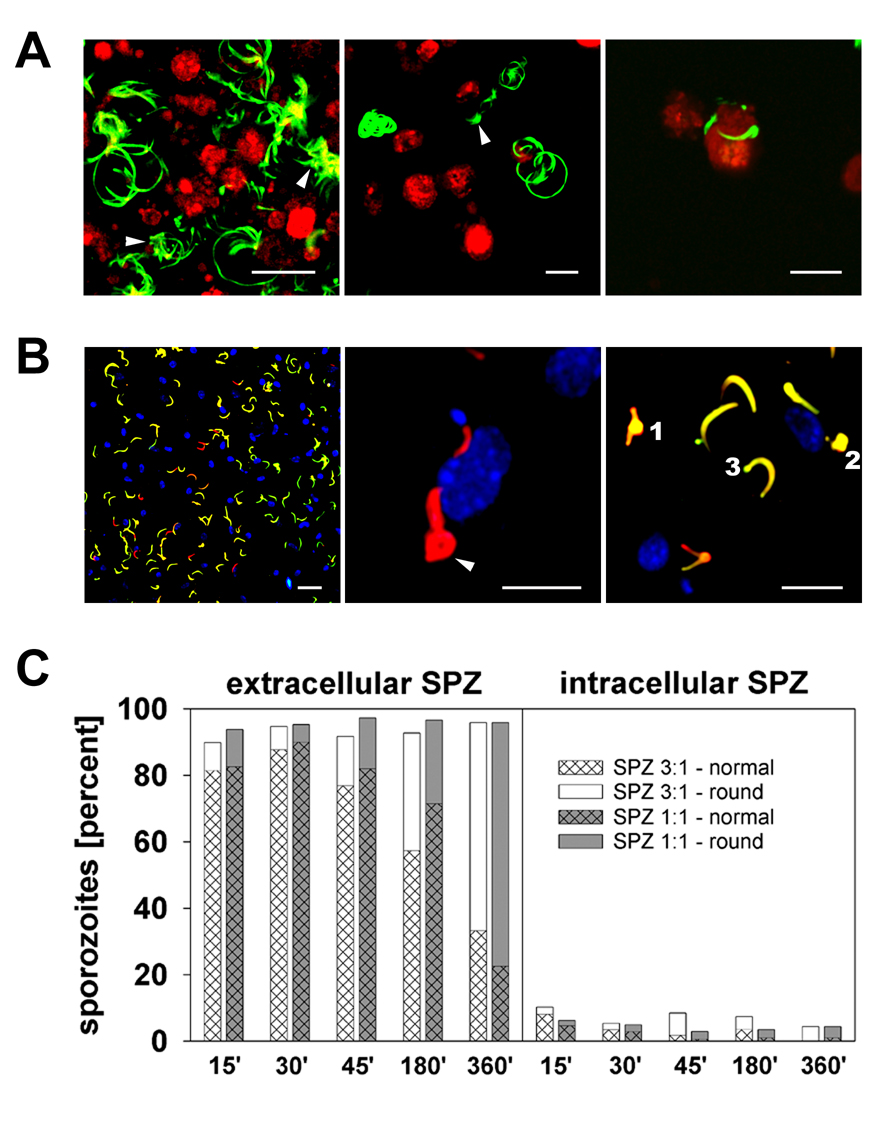

3.7. Sporozoite behavior in Kupffer cell cultures

To elucidate whether sporozoite contact with or migration through Kupffer cells was responsible for the observed alteration of cytokine secretion, we monitored the behavior of the parasites in real time. Live cell imaging with P. yoelii parasites that express GFP throughout the entire life cycle (PyGFP) (Tarun et al., 2006) demonstrated that most sporozoites did not make contact with Kupffer cells or the culture dish, but remained floating in the medium and exhibited Brownian motion. The small sub-population of adherent sporozoites showed the typical circular migration pattern, occasionally making contact with a Kupffer cell and gliding along its membrane (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Movie S1–Supplementary Movie S3). Invasion of or passage through Kupffer cells was observed only rarely. Enhancing parasite contact by low-speed centrifugation yielded an average of 0.5 and 1.5 attached sporozoites per Kupffer cell when sporozoite:Kupffer cell (SPZ:KC) ratios of 1:1 and 3:1 were used, respectively. This ratio of 0.5–1.5 attached parasites roughly corresponds to the in vivo situation, where one sporozoite interacts with one Kupffer cell. All in vitro experiments in this study were performed under these conditions.

Fig. 4.

Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites attach to and invade murine rine Kupffer cells in vitro. A) Life cell imaging of CellTracker red CMTP-loaded Kupffer cells co-cultivated with PyGFP sporozoites.(a and b) Circular or spiral trails indicate gliding motility of adherent sporozoites; the Brownian motion of non-adherent sporozoites is indicated by lateral or irregular displacement (arrows). (c) Two sporozoites in close association with a Kupffer cell. Maximum projections were derived from 50 frames acquired over a period of 160 s. Scale bars, 20 µm. B) Distinction of intra- and extracellular sporozoites. Kupffer cells exposed for 6 h to three P. yoelii sporozoites per cell were double-labeled with rabbit anti-P. yoelii circumsporozoite protein (CSP) in combination with GARFITC (extracellular sporozoites, yellow) and GAR-Texas Red (intracellular sporozoites, red). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (a) Most sporozoites are attached to the Kupffer cell surface and exhibit a normal crescent shape. (b) Two intracellular parasites, one of which is rounded (arrow), are located close to the nucleus of a Kupffer cell. (c) Extra- (yellow) and intracellular (red) sporozoites exhibit swelling of the nuclear region (1) or complete rounding (2). A few sporozoites carried a fluorescent blob at one cell pole (3). Scale bar, 20 µm (a), 10 µm (b and c). C) Quantification of intra- and extracellular sporozoites after various periods of co-incubation with Kupffer cells. Hatched fill represents normal sporozoites, homogeneous fill represents sporozoites with morphologic changes (B).

Previous work with mixed populations of non-parenchymal rat liver cells (Pradel and Frevert, 2001) or peritoneal macrophages (Danforth et al., 1980; Vanderberg et al., 1990) demonstrated that Plasmodium sporozoites are able to invade Kupffer cells and other macrophages in vitro. Because Kupffer cells are typically thinly spread in vitro, distinction of true cell traversal from mere sporozoite gliding over or under a cell is difficult to achieve by live cell imaging. Therefore, we analyzed the rate of invaded versus attached P. yoelii sporozoites in Kupffer cell cultures using a double labeling assay. A maximum of about 10% of the adherent sub-population of the parasites were intracellular after 15 min of co-cultivation (Fig. 4B). This number gradually decreased to approximately 4% after 6 h. Sporozoite-invaded Kupffer cells excluded fluorescent dextran (data not shown) confirming that parasite entry into phagocytic cells occurs by membrane invagination, not membrane wounding (Mota et al., 2001; Pradel and Frevert, 2001). Because sporozoite invasion was minimal, we consider the possibility of Kupffer cell traversal by multiple parasites highly unlikely. In fact, the near lack of invasion suggests a less intimate interaction compared with the sporozoite passage through Kupffer cells observed in vivo.

We noted that the morphology of the sporozoites in Kupffer cell cultures gradually changed. With increasing incubation time, progressively more intra- and extracellular sporozoites exhibited complete rounding or swelling in the nuclear region or at one of the cell poles (Fig. 4B, 4C). The total percentage of parasites showing these modifications ranged from 10–13% after 15 min to 66–76% after 6 h of co-cultivation. Thus, P. yoelii sporozoites remained intact in murine Kupffer cell cultures, but eventually appeared to transform to early EEF-like stages, similar to what has previously been observed in axenic culture (Kaiser et al., 2003).

3.8. Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites induce apoptosis in Kupffer cells

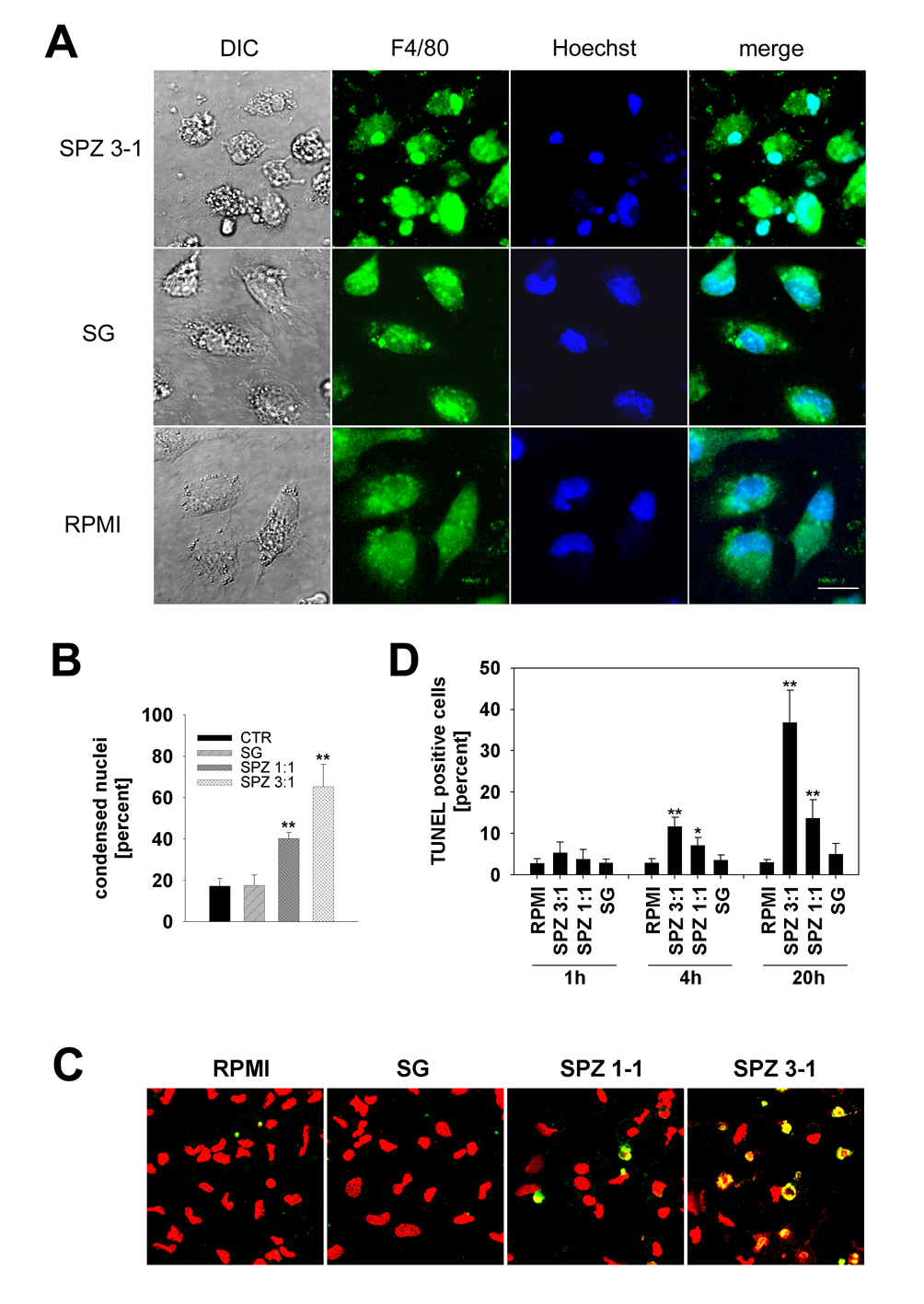

While imaging live PyGFP sporozoites, we noticed that some Kupffer cells exhibited alterations in cell shape such as rounding and blebbing (Fig. 4A). Similar to earlier in vitro observations with peritoneal macrophages (Danforth et al., 1980), we detected evidence for Kupffer cell death only upon co-incubation with sporozoites, not with uninfected SG extract or medium alone. The dramatic morphological alterations became even more obvious when Kupffer cell cultures were fixed after co-incubation with sporozoites and labeled with the tissue macrophage-specific surface marker F4/80. After 20 h of incubation, the cultures contained many rounded Kupffer cells and a large amount of F4/80-positive cell debris (Fig. 5A). Hoechst staining revealed that up to 65% of the Kupffer cell nuclei were condensed and fragmented (Fig. 5B). Cultures with control SG preparations showed no evidence of Kupffer cell alteration. Because cell membrane blebbing and nuclear condensation and fragmentation suggested death by apoptosis, we subjected Kupffer cell cultures (1 h, 4 h and 20 h after parasite addition) to TUNEL staining. After 20 h of exposure to sporozoites at ratios of 1:1 and 3:1, 13 ± 4% and 37 ± 8%, respectively, of the Kupffer cell nuclei were TUNEL-positive, while control SG extract had no effect (Fig. 5C, 5D). Thus, co-cultivation with P. yoelii sporozoites caused a dose-and time-dependent induction of apoptosis in Kupffer cells.

Fig. 5.

Plasmodium yoelii sporozoites induce apoptosis in Kupffer cells. A) Cultures were exposed for 20 h to three P. yoelii sporozoites per Kupffer cell (SPZ 3–1), fixed and labeled with mAb F4/80 followed by GAM-FITC (green). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Only sporozoite-exposed Kupffer cells exhibit nuclear condensation, fragmentation and blebbing of the cell membrane. Salivary gland (SG), uninfected SG extract; DIC, differential interference contrast; RPMI, medium control. Scale bar, 10 µm. B) Quantification of the number of condensed and/or fragmented nuclei (A). Data were expressed as mean percent ± S.D. in relation to the total number of condensed nuclei from triplicate wells. Ratios were three (SPZ 3:1) or one (SPZ 1:1) sporozoites per Kupffer cell. SG, uninfected SG extract. **, P < 0.01 in relation to control SG extract. (C) Confocal scans of Kupffer cells co-cultivated for 20 h with three (SPZ 3:1) or one (SPZ 1:1) P. yoelii sporozoites per cell. Control cells were exposed to SG extracts (SG) or medium (RPMI). TUNEL-positive cells appear yellow due to counterstaining with propidium iodide (red). D) Quantification of apoptotic Kupffer cells after 1 h, 4 h and 20 h of co-cultivation with P. yoelii sporozoites, see (C) for details. Data were expressed as mean percent of TUNEL-positive cells ± S D. from triplicate wells. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01 in relation to SG controls.

4. Discussion

The major finding of this study is that Plasmodium sporozoites modulate cytokine secretion by Kupffer cells towards an overall anti-inflammatory profile and eventually cause these hepatic macrophages to undergo programmed cell death. Stimulation ulation of Kupffer cells revealed that prior in vitro exposure to P. yoelii sporozoites induced a selective concentration- and time-dependent suppression in the production of the pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1, while secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was enhanced. Similarly, Kupffer cells purified from P. yoelii sporozoite-infected mice also produced lower TNF-α and higher IL-10 levels upon subsequent in vitro stimulation with LPS compared with Kupffer cells from SG extract-injected control mice. Sporozoite inactivation abrogated this shift in the cytokine profile indicating that parasite viability is necessary to modulate the Kupffer cell response. Further, it appears that sporozoite contact, but not invasion, was required for Kupffer cell modulation. During co-cultivation with Kupffer cells, P. yoelii sporozoites gradually transformed (Kaiser et al., 2003) but remained intact, while sporozoite-exposed Kupffer cells exhibited cell membrane blebbing, nuclear condensation, fragmentation and eventually became TUNEL-positive suggesting that apoptosis had been triggered. Together, these findings suggest that sporozoites render Kupffer cells insensitive to pro-inflammatory stimuli and eventually eliminate these macrophages by forcing them into programmed death.

Kupffer cells are central players in the regulation of the cytokine network of the liver, during homeostasis and infection (Knolle and Gerken, 2000), and they also serve as a significant systemic source for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1 and IL-10 (Decker, 1990). In addition to preventing liver injury (Van Ness et al., 1995), the second messenger cAMP is also an important regulator of the cytokine response. Similar to sporozoite exposure, elevation of the intracellular cAMP concentration with db-cAMP or by inhibition of adenylyl cyclase with IBMX significantly suppressed secretion of the pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-α and IL-6, and stimulated the anti-inflammatory IL-10 in Kupffer cells. This immunosuppressive effect of cAMP is in agreement with reports documenting that Kupffer cells and other macrophages respond to elevation of this second messenger with down-regulation of TNF-α and up-regulation of IL-10 (Aronoff et al., 2005; Dahle et al., 2005; Gobejishvili et al., 2006), both well-known regulators of inflammation caused by bacterial infection. In a previous study, we reported that Plasmodium sporozoites increase the intracellular cAMP concentration and inhibit the respiratory burst in murine Kupffer cells in an EPAC-dependent, but PKA-independent, fashion (Usynin et al., 2007). Here, we show that specific PKA activation with 6-MB-cAMP suppressed the production of TNF-α and IL-6, and increased the production of IL-10 upon stimulation of Kupffer cells with LPS, while the selective EPAC activator 8-CPT-2’-O-Me-cAMP had no effect. These results suggest that the CSP-mediated cAMP increase may have a dual effect on Kupffer cells: a short-term EPAC-regulated blockage of the respiratory burst and a long-term PKA-mediated modulation of the cytokine profile. Thus, by manipulating Kupffer cells, Plasmodium may be able to support its survival in the host.

Under natural transmission conditions, mosquitoes inject sporozoites into the avascular portion of the skin (Vanderberg and Frevert, 2004; Amino et al., 2006) together with saliva, a complex molecular cocktail with anti-haemostatic properties (Ribeiro, 1987). As expected, uninfected mosquito bites can activate mast cells and induce local inflammatory reactions (Demeure et al., 2005), but they can also trigger systemic Th1 type responses with increased levels of IL-12, IFN-γ and iNOS expression, which can surprisingly protect mice against challenge with P. yoelii sporozoites (Donovan et al., 2007). In contrast to natural transmission, Plasmodium sporozoites prepared from mosquito salivary glands are inevitably contaminated with large amounts of tissue debris, endotoxin, bacteria and other microorganisms (Mack et al., 1978) (Frevert, unpublished data). While such vector-derived contaminants normally do not reach the liver, vaccination/challenge studies frequently require defined parasite numbers and thus depend on the i.v. inoculation of isolated SG sporozoites. Because of their dominant clearance function, Kupffer cells must be expected to also remove most of the i.v. injected SG residues from the blood. The finding that SG extract from uninfected mosquitoes can increase the serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity indicates damage of the liver parenchyma due to Kupffer cell activation (Mota et al., 2001; Frevert et al., 2005; Baer et al., 2007a). Although contamination was reduced by subjecting sporozoites to anion exchange chromatography (Mack et al., 1978), traces of LPS still remained in our SG preparations. We attribute, at least partially, the finding that SG extract induced the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro to these bacterial contaminants. The effect of mosquito-derived contaminants may be important, because injection of uninfected SG extract induced a high degree of protection against challenge with P. berghei sporozoites or Plasmodium gallinaceum-infected mosquito bites (Alger et al., 1972; Rocha et al., 2004). While this protective effect may be beneficial when induction of an immune response is desired, elimination of microbial contamination, for instance by breeding and maintaining mosquitoes under sterile conditions (Luke and Hoffman, 2003), may be necessary to achieve optimal liver infection rates for biological studies.

Sporozoite exposure induced apoptosis in Kupffer cells. It remains to be determined whether the elevated cAMP levels, which can alter macrophage morphology (Rossi et al., 1998), or the ribotoxic properties of CSP (Frevert et al., 1998) are involved in the initiation of the death program. More work is also required to elucidate how apoptosis relates to the observed cytokine changes because in lymphoid cells, for example, apoptosis can induce the rapid production of IL-10 (Gao et al., 1998). Regardless of the mechanism involved, Kupffer cell elimination by apoptosis may conceivably provide two beneficial effects for the hepatic phase of a malaria infection. Firstly, dying Kupffer cells are likely unable to produce cytokine and chemokine profiles adequate to convey a danger signal to the host’s immune system (DosReis and Barcinski, 2001). Second, injection of sporozoites had a clear suppressive effect on the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and down-modulated the expression of MHC class I molecules of a large proportion of the Kupffer cell population (Steers et al., 2005). One possible explanation for this phenomenon comes from the finding that phagocytic uptake of apoptotic cells induces macrophages to increase the production of the anti-inflammatory mediators IL-10 and TGF-β and to reduce the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8, even after stimulation with LPS (Voll et al., 1997). The clearance of damaged or apoptotic cells is extremely rapid and efficient and Kupffer cells play a dominant role in these mechanisms (Terpstra and van Berkel, 2000). Taking these data together, we propose that Kupffer cells that succumb to apoptosis after encountering a sporozoite are expelled from the sinusoidal cell layer and phagocytozed by neighboring Kupffer cells or other phagocytes located further downstream in the sinusoid. These macrophages respond by down-modulating MHC class I expression and secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines, which allows the overall immunosuppressive effect to expand from the site of sporozoite entry into the liver towards the central vein, thus providing a safe environment for EEF development.

Accumulating evidence supports the notion that malaria sporozoites are able to manipulate the immune function of various cells of the host. i) Krzych and colleagues reported that radiation-attenuated Plasmodium berghei sporozoites induce up-regulation of MHC class I, CD40 and CD80/CD86 expression and increase the production of IL-12p40, while infectious sporozoites are able to down-modulate MHC class I expression in murine Kupffer cells in vivo (Steers et al., 2005). This may be one reason why Kupffer cells appear not to present antigen to CSP-specific effector CD8+ T cells (Chakravarty et al., 2007). ii) By engaging the scavenger receptor LRP, P. berghei and P. yoelii sporozoites increase the intracellular cAMP level and inhibit the respiratory burst in Kupffer cells (Usynin et al., 2007). iii) Plasmodium gallinaceum infects and develops in Kupffer cells from chickens (Huff, 1963; Frevert et al., 2007). To transform these hepatic macrophages into nurse cells, this avian malaria parasite, like many other evolutionarily related Plasmodium species, therefore likely possesses mechanisms for macrophage deactivation. iv) Liver stages from mammalian Plasmodium species are able to prevent apoptosis in infected hepatocytes (Leiriao et al., 2005; van de Sand et al., 2005; van Dijk et al., 2005; Sturm et al., 2006; Baer et al., 2007a), thereby keeping their host cells alive until merozoite release is accomplished. In conclusion, Plasmodium appears to modulate basic anti-microbial functions of Kupffer cells to support the enormous growth of its liver stages culminating in the release of thousands of merozoites into the blood. A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms may take us one step closer to controlling this deadly parasite.

Supplementary Material

Life cell imaging of CellTracker red CMTP-loaded Kupffer cells (red) co-cultivated with PyGFP sporozoites (green). The movie shows a merge of differential interference with the green and red channels. Note that the sporozoite glides along the Kupffer cell surface, loses cell contact, and exhibits Brownian motion. The 50 frames of the movie were acquired over a period of 160 s.

Life cell imaging of CellTracker red CMTP-loaded Kupffer cells (red) co-cultivated with PyGFP sporozoites (green). The sporozoite glides along and possibly through Kupffer cells. The 50 frames of the movie were acquired over a period of 160 s.

Life cell imaging of CellTracker red CMTP-loaded Kupffer cells (red) co-cultivated with PyGFP sporozoites (green). Differential interference contrast channel is merged with the green and red channel. Please note that the sporozoite glides along the surface of Kupffer cells and culture dish. Finally, the sporozoites lose surface contact and exhibit Brownian motion. The 100 frames of the movie were acquired over a period of 320 s.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Mauricio Calvo-Calle (University of Massachusetts School of Medicine), Urszula Krzych (Walter Reed Army Institute for Research) and Jerome Vanderberg (NYU School of Medicine) for critically reviewing the manuscript. The work was supported by NIH grants RO1 AI51656 and S10 RR019288 to UF and a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Liver Foundation to CK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Note: Supplementary data associated with this article.

References

- Alger NE, Harant JA, Willis LC, Jorgensen GM. Sporozoite and normal salivary gland induced immunity in malaria. Nature. 1972;238:341. doi: 10.1038/238341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amino R, Thiberge S, Martin B, Celli S, Shorte S, Frischknecht F, Menard R. Quantitative imaging of Plasmodium transmission from mosquito to mammal. Nat Med. 2006;12:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nm1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff DM, Canetti C, Serezani CH, Luo M, Peters-Golden M. Cutting edge: macrophage inhibition by cyclic AMP (cAMP): differential roles of protein kinase A and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP-1. J Immunol. 2005;174:595–599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer K, Klotz C, Kappe SHIK, Schnieder T, Frevert U. Release of hepatic Plasmodium yoelii merozoites into the pulmonary microvasculature. PLoS Pathog. 2007a;3:e171. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer K, Roosevelt M, Clarkson AB, Jr, van Rooijen N, Schnieder T, Frevert U. Kupffer cells are obligatory for Plasmodium yoelii sporozoite infection of the liver. Cell Microbiol. 2007b;9:397–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengis-Garber C, Gruener N. Involvement of protein kinase C and of protein phosphatases 1 and/or 2A in p47phox phosphorylation in formylmet-Leu-Phe stimulated neutrophils: studies with selective inhibitors RO 31-8220 and calyculin A. Cell Signal. 1995;7:721–732. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(95)00040-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher BA, Kim L, Johnson PF, Denkers EY. Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites inhibit proinflammatory cytokine induction in infected macrophages by preventing nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2001;167:2193–2201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor HM, Dumont AE. Hepatic suppression of sensitization to antigen absorbed into the portal system. Nature. 1967;215:744–745. doi: 10.1038/215744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty S, Cockburn IA, Kuk S, Overstreet MG, Sacci JB, Zavala F. CD8(+) T lymphocytes protective against malaria liver stages are primed in skin-draining lymph nodes. Nat Med. 2007;13:1035–1041. doi: 10.1038/nm1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispe IN, Giannandrea M, Klein I, John B, Sampson B, Wuensch S. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of liver tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:101–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahle MK, Myhre AE, Aasen AO, Wang JE. Effects of forskolin on Kupffer cell production of interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor alpha differ from those of endogenous adenylyl cyclase activators: possible role for adenylyl cyclase 9. Infect Immun. 2005;73:7290–7296. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7290-7296.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danforth HD, Aikawa M, Cochrane AH, Nussenzweig RS. Sporozoites of mammalian malaria: attachment to, interiorization and fate within macrophages. J Protozool. 1980;27:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1980.tb04680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker K. Biologically active products of stimulated liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) Eur J Biochem. 1990;192:245–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demeure CE, Brahimi K, Hacini F, Marchand F, Peronet R, Huerre M, St-Mezard P, Nicolas JF, Brey P, Delespesse G, Mecheri S. Anopheles mosquito bites activate cutaneous mast cells leading to a local inflammatory response and lymph node hyperplasia. J Immunol. 2005;174:3932–3940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan MJ, Messmore AS, Scrafford DA, Sacks DL, Kamhawi S, McDowell MA. Uninfected mosquito bites confer protection against infection with malaria parasites. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2523–2530. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01928-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DosReis GA, Barcinski MA. Apoptosis and parasitism: from the parasite to the host immune response. Adv Parasitol. 2001;49:133–161. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(01)49039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frevert U, Galinski MR, Hügel F-U, Allon N, Schreier H, Smulevitch S, Shakibaei M, Clavijo P. Malaria circumsporozoite protein inhibits protein synthesis in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:3816–3826. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frevert U. Sneaking in through the back entrance: The biology of malaria liver stages. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frevert U, Engelmann S, Zougbédé S, Stange J, Ng B, Matuschewski K, Liebes L, Yee H. Intravital observation of Plasmodium berghei sporozoite infection of the liver. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frevert U, Usynin I, Baer K, Klotz C. Nomadic or sessile: can Kupffer cells function as portals for malaria sporozoites to the liver? Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1537–1546. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frevert U, Späth G, Yee H. Exoerythrocytic development of Plasmodium gallinaceum in the White Leghorn chicken. Int J Parasitol. 2007;38:655–672. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froh M, Konno A, Thurman G. Isolation of Liver Kupffer cells. In: Bus J, Costa L, Hodgson E, Lawrence D, Reed D, editors. Current Protocols in Toxicology. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. pp. 14.14.11–14.14.12. [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Herndon JM, Zhang H, Griffith TS, Ferguson TA. Antiinflammatory effects of CD95 ligand (FasL)-induced apoptosis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:887–896. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobejishvili L, Barve S, Joshi-Barve S, Uriarte S, Song Z, McClain C. Chronic ethanol-mediated decrease in cAMP primes macrophages to enhanced LPS-inducible NF-kappaB activity and TNF expression: relevance to alcoholic liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G681–G688. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00098.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff CG. Experimental research on avian malaria. In: Dawes B, editor. Advances in Parasitology. London and New York: Academic Press; 1963. pp. 1–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hügel FU, Pradel G, Frevert U. Release of malaria circumsporozoite protein into the host cell cytoplasm and interaction with ribosomes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;81:151–170. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02701-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob AI, Goldberg PK, Bloom N, Degenshein GA, Kozinn PJ. Endotoxin and bacteria in portal blood. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:1268–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser K, Camargo N, Kappe SH. Transformation of sporozoites into early exoerythrocytic malaria parasites does not require host cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1045–1050. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambayashi T, Wallin RP, Ljunggren HG. cAMP-elevating agents suppress dendritic cell function. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:903–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knolle PA, Gerken G. Local control of the immune response in the liver. Immunol Rev. 2000;174:21–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knook DL, Sleyster EC. Separation of Kupffer and endothelial cells of the rat liver by centrifugal elutriation. Exp Cell Res. 1976;99:444–449. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopydlowski KM, Salkowski CA, Cody MJ, van Rooijen N, Major J, Hamilton TA, Vogel SN. Regulation of macrophage chemokine expression by lipopolysaccharide in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;163:1537–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper J, Brouwer A, Knook DL, Berkel TJCv. Kupffer and sinusoidal endothelial cells. In: Arias IM, Boyer JL, Fausto N, Jakoby WB, Schachter DA, Shafritz DA, editors. The Liver: Biology and Pathobiology. New York: Raven Press, Ltd.; 1994. pp. 791–818. [Google Scholar]

- Laskin DL. Role of hepatic macrophages in inflammation and tissue injury. In: Vidal-Vanaclocha F, editor. Functional Heterogeneity of Liver Tissue. Austin: R.G. Landes Company; 1997. pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Leiriao P, Albuquerque SS, Corso S, van Gemert GJ, Sauerwein RW, Rodriguez A, Giordano S, Mota MM. HGF/MET signalling protects Plasmodium-infected host cells from apoptosis. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:603–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie DB, Aber VR, Jackett PS. Phagosome-lysosome fusion and cyclic adenosine 3':5'-monophosphate in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium bovis BCG or Mycobacterium lepraemurium. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;110:431–441. doi: 10.1099/00221287-110-2-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke TC, Hoffman SL. Rationale and plans for developing a non-replicating, metabolically active, radiation-attenuated Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite vaccine. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:3803–3808. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack SR, Vanderberg JP, Nawrot R. Column separation of Plasmodium berghei sporozoites. J Parasitol. 1978;64:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meis JFGM, Verhave JP, Jap PHK, Meuwissen JHET. An ultrastructural study on the role of Kupffer cells in the process of infection by Plasmodium berghei sporozoites in rats. Parasitology. 1983;86:231–242. doi: 10.1017/s003118200005040x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota MM, Pradel G, Vanderberg JP, Hafalla JCR, Frevert U, Nussenzweig RS, Nussenzweig V, Rodriguez A. Migration of Plasmodium sporozoites through cells before infection. Science. 2001;291:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5501.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paludan SR. Synergistic action of pro-inflammatory agents: cellular and molecular aspects. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:18–25. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradel G, Frevert U. Malaria sporozoites actively enter and pass through rat Kupffer cells prior to hepatocyte invasion. Hepatology. 2001;33:1154–1165. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JM. Role of saliva in blood-feeding by arthropods. Annu Rev Entomol. 1987;32:463–478. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.32.010187.002335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman LK, Klingenstein RJ, Richman JA, Strober W, Berzofsky JA. The murine Kupffer cell. I. Characterization of the cell serving accessory function in antigen-specific T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 1979;123:2602–2609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha AC, Braga EM, Araujo MS, Franklin BS, Pimenta PF. Effect of the Aedes fluviatilis saliva on the development of Plasmodium gallinaceum infection in Gallus (gallus) domesticus. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:709–715. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000700008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AG, McCutcheon JC, Roy N, Chilvers ER, Haslett C, Dransfield I. Regulation of macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by cAMP. J Immunol. 1998;160:3562–3568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedman PC, Macfie J, Sagar P, Mitchell CJ, May J, Mancey-Jones B, Johnstone D. The prevalence of gut translocation in humans. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:643–649. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steers N, Schwenk R, Bacon DJ, Berenzon D, Williams J, Krzych U. The immune status of Kupffer cells profoundly influences their responses to infectious Plasmodium berghei sporozoites. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2335–2346. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm A, Amino R, van de Sand C, Regen T, Retzlaff S, Rennenberg A, Krueger A, Pollok JM, Menard R, Heussler VT. Manipulation of host hepatocytes by the malaria parasite for delivery into liver sinusoids. Science. 2006;313:1287–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1129720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarun AS, Baer K, Dumpit RF, Gray S, Lejarcegui N, Frevert U, Kappe S. Quantitative isolation and in vivo imaging of malaria parasite liver stages. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra V, van Berkel TJ. Scavenger receptors on liver Kupffer cells mediate diate the in vivo uptake of oxidatively damaged red blood cells in mice. Blood. 2000;95:2157–2163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usynin I, Klotz C, Frevert U. Malaria circumsporozoite protein inhibits the respiratory burst in Kupffer cells. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2610–2628. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Sand C, Horstmann S, Schmidt A, Sturm A, Bolte S, Krueger A, Lutgehetmann M, Pollok JM, Libert C, Heussler VT. The liver stage of Plasmodium berghei inhibits host cell apoptosis. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:731–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk MR, Douradinha B, Franke-Fayard B, Heussler V, van Dooren MW, van Schaijk B, van Gemert GJ, Sauerwein RW, Mota MM, Waters AP, Janse CJ. Genetically attenuated, P36p-deficient malarial sporozoites induce protective immunity and apoptosis of infected liver cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12194–12199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500925102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ness K, Podkameni D, Schwartz M, Boros P, Miller C. Dibutyryl cAMP reduces nonparenchymal cell damage during cold preservation of rat livers. J Surg Res. 1995;58:728–731. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1995.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderberg J, Gwadz W. The transmission by mosquitoes of Plasmodia in the laboratory. In: Kreier J, editor. Malaria: Pathology, vector studies and culture Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 153–234. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderberg JP, Chew S, Stewart MJ. Plasmodium sporozoite interactions with macrophages in vitro: a videomicroscopic analysis. J Protozool. 1990;37:528–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1990.tb01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderberg JP, Frevert U. Intravital microscopy demonstrating antibody-mediated immobilization of Plasmodium berghei sporozoites injected into skin by mosquitoes. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voll RE, Herrmann M, Roth EA, Stach C, Kalden JR, Girkontaite I. Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1997;390:350–351. doi: 10.1038/37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wake K, Decker K, Kirn A, Knook DL, McCuskey RS, Bouwens L, Wisse E. Cell biology and kinetics of Kupffer cells in the liver. Int Rev Cytol. 1989;118:173–229. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60875-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler MD. Endotoxin and Kupffer cell activation in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:300–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zidek Z. Adenosine - cyclic AMP pathways and cytokine expression. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1999;10:319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Life cell imaging of CellTracker red CMTP-loaded Kupffer cells (red) co-cultivated with PyGFP sporozoites (green). The movie shows a merge of differential interference with the green and red channels. Note that the sporozoite glides along the Kupffer cell surface, loses cell contact, and exhibits Brownian motion. The 50 frames of the movie were acquired over a period of 160 s.

Life cell imaging of CellTracker red CMTP-loaded Kupffer cells (red) co-cultivated with PyGFP sporozoites (green). The sporozoite glides along and possibly through Kupffer cells. The 50 frames of the movie were acquired over a period of 160 s.

Life cell imaging of CellTracker red CMTP-loaded Kupffer cells (red) co-cultivated with PyGFP sporozoites (green). Differential interference contrast channel is merged with the green and red channel. Please note that the sporozoite glides along the surface of Kupffer cells and culture dish. Finally, the sporozoites lose surface contact and exhibit Brownian motion. The 100 frames of the movie were acquired over a period of 320 s.