Abstract

Current Western medical treatment lays its main emphasis on evidence-based medicine (EBM) and cure is assessed by quantifying the effects of treatment statistically.

In contrast, in Chinese medicine, cure is generally assessed by evaluating the patient's “pattern” (Zheng) [cf. Glossary] and medicines are prescribed according to this. We believe that traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) cannot be evaluated precisely according to Western principles, in which a constant amount of the same medicine is given to a group of patients to be evaluated. When assessing cure using TCM, Zheng is more important than the determination of medical effects. This means that quantitative evaluation of TCM treatment can be very difficult.

In this paper, we focused on the Yin-Yang [cf. Glossary] balance to determine Zheng, and at the same time attempted to determine the treatment effects by applying the concept of regulation of Yin-Yang according to chronotherapeutic principles.

According to Zheng, advanced cancer patients generally lack both Yin and Yang. Chinese medical treatment therefore seeks to supplement both Yin and Yang. However, we divided patients into two groups and compared them with respect to survival. One group was administered a predominantly Yang (Qi) [cf. Glossary] tonic herbal treatment during the daytime, while the other group was administered Yin (Blood) [cf. Glossary] tonics during night time.

A comparison of the results of treatment showed that the patients in the group receiving Yang (Qi) replenishment during the daytime lived longer than patients receiving Yin (Blood) nourishment during the night. Moreover, the patients in the daytime Yang (Qi) replenishment group also fared significantly better than patients treated solely by Western methods.

Keywords: Chinese medicine, Yin, Yang, cAMP, cGMP, Chronotherapy

1. Introduction

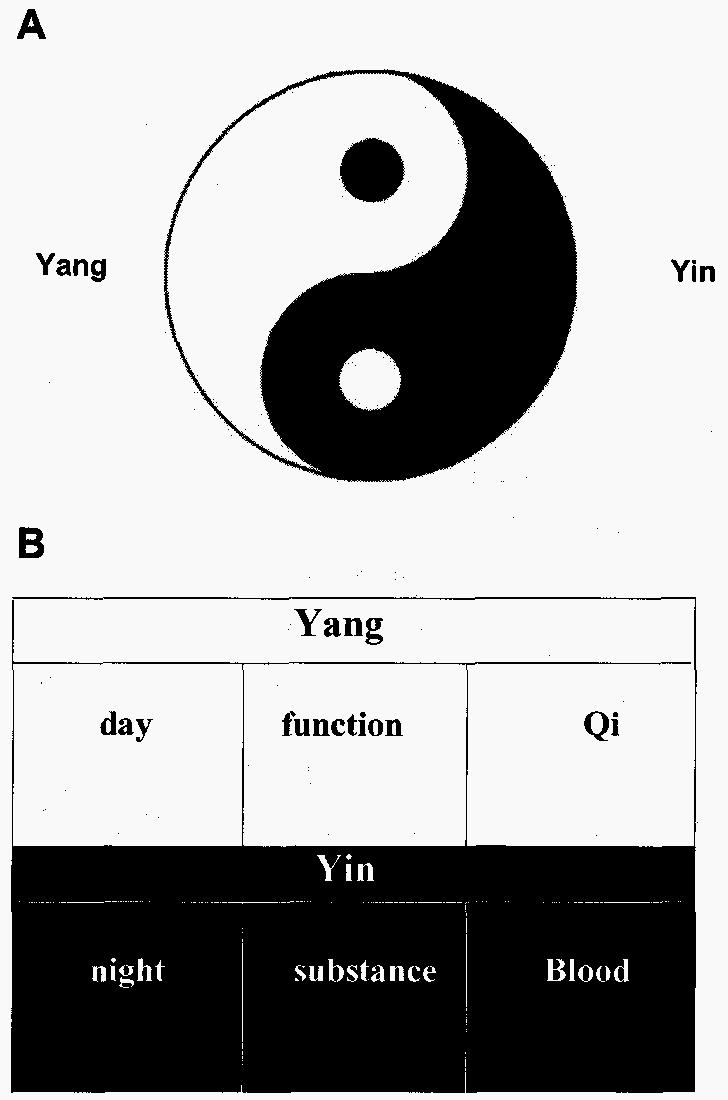

Traditional Chinese natural philosophy has been said to be based on the Zhou Yi [cf. Glossary] [23,29]. Originally, in the primordial state, there was “ONE”, which means unity by Chinese word and was then considered to give rise to the two complementary forces Yin and Yang [cf. Glossary]. Each of these forces included aspects of the opposite: Yin is contained within Yang, and Yang within Yin [5].

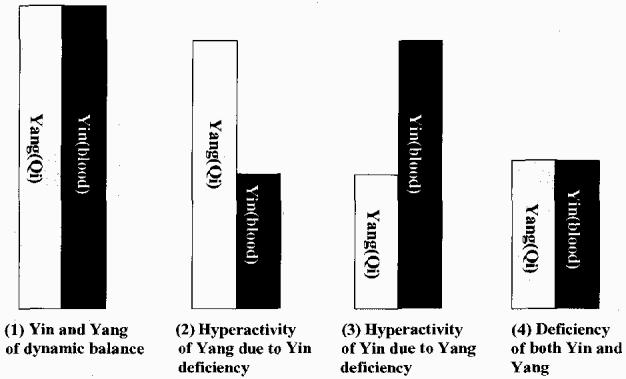

Through mutual dependence, alternate waxing and waning and repeated movements of contraposition and integration, a dynamic balance was considered to be maintained [3].

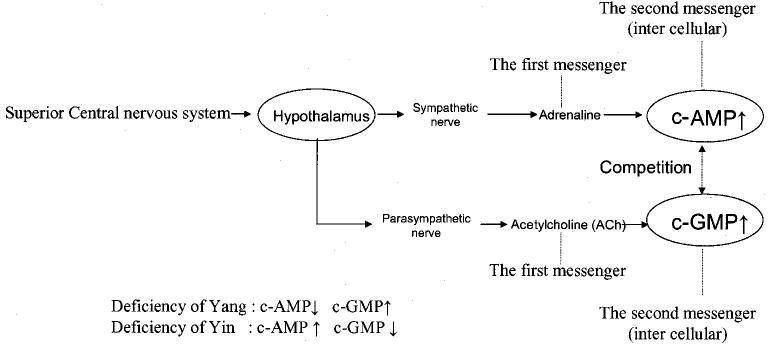

According to ancient Chinese theories, from the primordial chaos the Yang Qi [cf. Glossary.] first formed heaven, while the Yin Qi sank down to form earth. As shown in Fig. 1(1), this also included the temporal concepts of day and night. The black circle within the white of the day represents the sun, while the white circle within the black of the night represents the moon.

Fig. 1.

Yin (white portion) and Yang (black portion)

(1) Tai Ji illustration [cf. Glossary]

(2) A classification of Yin and Yang.

The changes of the sun and moon in the heavens led to theories related to astronomy, meteorology, and also medicine, with the human body considered to be a microcosmos.

In the field of Chinese medicine, disease was considered to be the manifestation of Yin-Yang imbalance and a complete separation of Yin and Yang meant death.

Within the living body, aspects of substance or form were designated Yin, and functional aspects Yang. Hence, Qi defined as the most basic energy of which the world is comprised is categorized as Yang and Blood which has functions of nourishing and moistening the whole body as Yin (Fig. 1 (2)).

The concept of time in Chinese medicine recognizes diurnal, monthly, and yearly rhythms (Table 1). Daytime is classified as Yang and night time Yin, summer as Yang and winter as Yin. Moreover, the movements of the moon are said to cause the body to shift from a state of excess at full moon towards deficiency or emptiness at new moon [13].

Table 1.

The concept of time in Chinese medicine

| Rhythm | Time | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Diurnal rhythm |

Day — Yang | Yang tonic (support) |

| Night — Yin |

Yin tonic (support) |

|

| 2) Monthly rhythm |

Full moon —Excess | Reducing (Eliminating pathogenic facters) |

| New moon —Deficiency |

Reinforcing (Strengthening the body resistance) |

|

| 3) Yearly rhythm | Summer — Yang | Yang tonic (support) |

| Winter — Yin | Yin tonic (support) |

As a basic therapeutic principle, it is advisable to replenish Yang during periods of abundant Yang and similarly, to augment Yin during periods of abundant Yin. Tonifying (supporting) Yang in advance during periods of abundant Yang will also ensure that Yang later remains in balance as a result of the transformation of Yang to Yin [13].

Generally, since chronic diseases of the respiratory system tend to worsen during the winter, tonification of Yang preceding summer is said to be beneficial. Similarly, for childhood allergies worsening during spring, tonifying Yin during winter is said to be helpful.

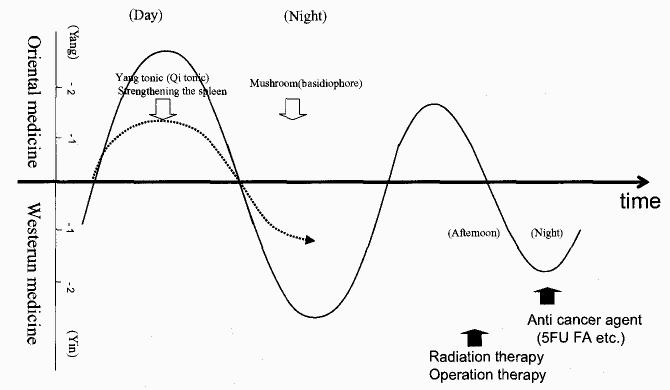

Fig. 2 depicts the fluctuations (waxing and waning) of Yin and Yang; health is considered a state of abundant Qi and Blood and a good balance between Yin and Yang.

Fig. 2.

Balance of Yin and Yang.

In cases of Yin deficiency, treatment requires enrichment of Yin (Yin tonics) and supplementation of the Blood (Blood tonics) during the night, while in cases of Yang deficiency, supplementation of Yang (Yang tonics) and Qi are required (Qi tonics) during the daytime. When both forces are depleted, treatment involves Yang supplementation and Yin enrichment (Yin and Yang tonics), as well as augmentation of both Qi and Blood (Qi and Blood tonics) during both the day and night time.

Next, it is necessary to discuss the system of Organs (Zhang-Fu) [cf. Glossary], and Channels-Collaterals [cf. Glossary] and their relationship to Chinese chronotherapy.

First, to explain chronotherapy it is important to consider the temporal cycles occurring in the body, which reflect those of the natural world, and the flow of Qi that is said to circulate within the body. The paths of this flow of Qi are known as Channels.

The circulation of Qi in the Channels and Collaterals is said to relate to circadian rhythms. Two types of Qi circulate within the Channels and Collaterals; nutritive Qi, which circulates at the surface of the body, and defensive Qi which is found at the surface and in the five viscera (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney). Nutritive Qi fluctuates with time and this concept is applied in an acupuncture and moxibustion therapy method called the “Ziwuluzhu method” [25]. Regulation of nutritive Qi is often targeted in chronotherapy of musculoskeletal and nervous system disorders. On the other hand, defensive Qi is said to circulate in the Yang Channels at the surface in daytime and to circulate 25 times through each of the five viscera at night [4]. Therefore, this concept is applied to visceral disorders; the stimulation of Yang Channels in the daytime affects the viscera, which are Yin during the night [20]. Thus, thinking of the Zang Fu (viscera and bowels) and Channels system recommends supplementing Qi (Yang) during the daytime in advance when Yin has been depleted.

In this way, traditional Chinese Medicine provides individualized care adapted to the physical condition of patients with the imbalance of Yin and Yang and their respective symptoms, and also considers the relevant temporal aspects. This may be considered an evidence-based medicine (EBM) approach that takes into account individual differences of the host that pertain to the relevant pattern (Zheng) [cf. Glossary].

2. Clinical experiences of Chinese medicine for patients with advanced cancers

Table 2 summarizes the therapeutic course of seven patients with advanced cancer treated according to the principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine. All patients had stage III or IV tumors with lymph node metastasis, invasion to other organs, or distant metastases.

Table 2.

Patients had gastric, colon, breast or lung cancer. The group which received tonification of Qi and Yang is represented (Qi and Yang tonic) in white and that which was given Blood and Yin Enrichment (Blood and Yin tonic) in black

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age and sex | 71year-old Female |

71year-old Male | 70year-old Male | 39year-old Female |

38year-old Female |

46year-old Male | 65year-old Male |

| cancer | Stomach | Stomach | Rectum | Breast | Breast | Lung (scc) | Lung (adeno) |

| Stage | stage IV | stage IV | Duke D | stage IV | stage IV | stage IIIA | stage IIIA |

| TNM classification | T3N4P0H0 | T2N4P0H0 | T2bN1bM1 | T3bN2M1 | T3N2M0 | T3N1M0 | |

| Metastasis | Lymph node metastasis (paraAo) |

Lymph node metastasis |

Lung metastasis | Lymph node metastasis Pleural invasion |

Lymph node metastasis Skin invesion |

Neck lymph node metastasis/ Superior vena caval syndrome |

Pleural invasion |

| Operation | Distal gastrectomy |

Total gastrectomy | Low anterior resection |

Modified radical mastectomy |

Modified radical mastectomy |

||

| Treatment of Western Medicine |

Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy FEC for 5 courses) Hormone therapy (LH-RHagonist) |

Chemotherapy FEC for 5 courses) Hormone therapy (TAM) Radiation therapy |

Radiation therapy Chemotherapy (TAX • CBDCA) Immunotherapy (SSM) (LAK) |

Radiation therapy Chemotherapy (TAX/EGFR- TKI) |

||

| Syndrome of Chinese Medicine |

Fire due to Yin deficiency Blood stasis |

Fire duw to Yin deficiency |

Deficiency of QI and Yin Blood stasis |

Deficiency of Qi and Yin Stagnancy of the Liver- Qi |

Fire due to Yin deficiency /Blood stasis /Stagnancy of the Liver-Qi |

Fire due to Yin deficiency/Retention of Phlegm and Fluid |

Deficiency of QI and Yin Retention of Phlegm and Fluid |

| Treatment of Chinese Medicine |

Buzhong yiqi tang + addition /Tian xian cap. /Xi huang wan |

Shiquan dabu tang | Yiguan fian + Shengmai san /Resolving Heat- Phlegm |

Huang qi guizhi wu wu tang + Qi tonic /Sootning the depressed Liver • chest oppression/Reduce phlegm |

Yiguan fian + Soothing the depressed liver /Promoting blood circulation |

Xeng ye tang /Ruan jian /Heat-clearing and Detoxicating drug |

Buzhong yiqi tang + Phellinus linteus /Multicolored polypole |

| Prognosis after operation |

alive, 5years | alive, 9years | deceased, 2years | alive, 5years | deceased, 3.5years |

deceased, 1year | alive, 5years |

Foot note

TNM : UICC Stage classification

UICC : Union International Centre Cancer

T : Primary tumor

N : Regional lymph node

M : Distant metastasis

P : Peritoneal metastasis

H : Liver metastasis

UFT : tegaful+uracil

FEC : fluorouracil+epirubisin+cyclophosphamide

LH-RH agonist : leuprorelin acetate

TAM : tamoxifen citrate

TAX : docetaxel

CBDCA : carboplatin

SSM : specific substance MARUYAMA

LAK : lymphokine-activated Killer

EGFR-TKI : Gefitinibinib

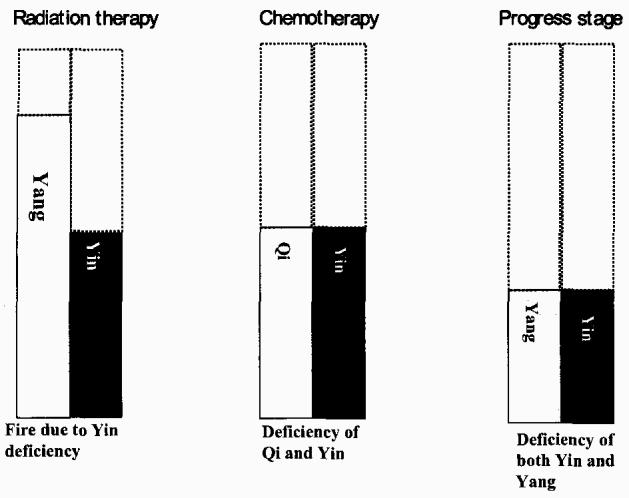

Underlying diseases were gastric cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer, and lung cancer. Deficiency of Yin [cf. Glossary] was observed in all patients.

Diagnostic breakdown was as follows: patients who underwent radiotherapy exhibited “Fire due to Yin deficiency” [cf. Glossary]; after the administration of chemotherapeutic agents, patients displayed “Deficiency of Qi and Yin” [cf. Glossary]; and patients in the terminal phase of cancer had “Deficiency of both Yin and Yang” [cf. Glossary] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Yin-Yang balance in cancer patients according to oncologic/therapeutic status. Excess of Yang is expressed as fire.

In the case of patients with Yin deficiency, we have shown survival outcomes for the commonly-used approach of night time Yin enrichment (Yin tonic), compared with tonification of Spleen Qi during the daytime [cf. Glossary] [2] [17]. The group receiving tonification of Qi and Yang (Qi and Yang tonics) is represented by white, and the group receiving Blood and Yin enrichment (Blood and Yin tonics) by black (Table 2).

We divided the seven advanced cancer patients into two groups according to Chinese medical symptoms and signs, irrespective of cancer region. Four cases were treated with Yang (Qi) tonics and three cases with Yin (Blood) tonics.

The main Chinese herbal [cf. Glossary]: Yin and Yang tonics used were as follows.

- 1) Yang (Qi) Supporting group.

- i) Buzhong -yiqi-tang.

- ii) Shiquan-da-bu-tang.

- 2) Yin (Blood) Supporting group.

- i) Yi-guan-fian.

- ii) Xeng-ye-tang.

- iii) Sheng-mai-san.

Four patients with gastric, breast or lung cancer who received daytime herbal therapy aimed at tonifying Qi and strengthening the Spleen have survived over 5 years. However, no therapeutic effect was achieved in any of these patients using night time Yin tonicsl In general, 5-year survival is reported to be 9.4% for stage IV gastric cancer, 10.9% for stage IV breast cancer, 17.7% for Dukes D colorectal cancer, and 30.3% for stage IIIa lung cancer (data from the National Cancer Hospital, Japan. (http://www.ncc.go.jp/jp/statistics/2OO3/datalO_2.pdf) It was also noted that cases receiving daytime Yang (Qi) tonics lived longer than 5 years. And the patients in the daytime Yang (Qui) replenishment group fared significantly better than patients treated solely by Western methods.

3. Discussion

From a Western medical point of view, the following observations can be made.

In 1970, Nelson Goldberg discovered that the physiological activities of neurotransmitters and hormones as well as the target cells of biologically active substances are mediated via intracellular cyclic nucleotides.

The concentration of the cyclic nucleotides cAMP/cGMP fluctuates and they appear to have mutually antagonistic actions. Accordingly, “Yin-Yang theory” has been applied to the regulation of cellular function. [8,9,11,12].

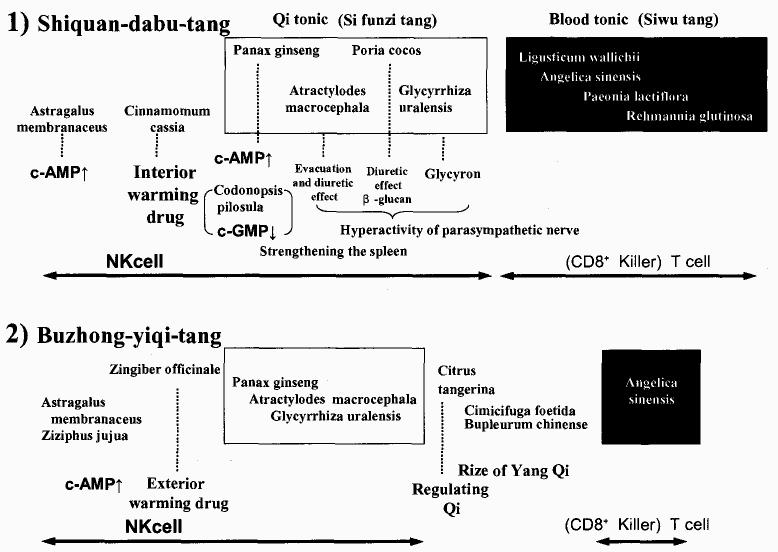

Furthermore in a Chinese clinical study, Guang An-fang reported that Yang deficiency corresponds to a decrease in cAMP, and Yin deficiency to an increase in cAMP [10,20,28] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Regulation of the nervous system: Gnang An-fang reported that Yang deficiency corresponds to a decrease in cAMP, and Yin deficiency to an increase in cAMP.

The present report provides data pertaining to cyclic nucleotides in advanced cancer patients (Table 3). Concentrations of cyclic nucleotides in the plasma of blood were determined by the ultrasensitive radioimmunoassay method: (The DCC [Dextran-coated Charcoal] Method using 125I-labeled SCAMP- TME [125I-labeled Succinyl Cyclic AMP Tyrosin Methyl Ester]) [14].

Table 3.

Differentiation of syndrome and cyclic nucleotide

| Deficiency of Yang patient; cAMP↓ / cGMP ↑ (A fall of ratio) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Deficiency of Yin patient; cAMP↑ / cGMP ↓ (A rise of ratio) | |||

| CAMP 11∼21pmol/ml) |

c GMP (1.8∼4.8pmol/ml) |

cAMP/c MP ratio |

|

| Case1:alive,5years after operation Qi tonic and strengthening the spleen |

14.0 |

3.0 |

4.7 |

| Case3:deceased, 2years after operation Yin tonic case |

13.0 |

1.5 ↓ |

8.7 |

| Case 6:deceased, 1year after chemotherapy Yin tonic case |

35.0 ↑ | 25.0 ↑ | 1.4 ↓ |

Despite Yin deficiency in these patients, Qi tonics normalized cAMP, and in one patient with terminal gastric cancer (case 1) a favorable course was observed.

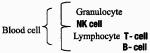

Abo et al. [1] described a regulatory system regarding control of granulocytes and lymphocytes by the autonomic nervous system. Considering that granulocytes and lymphocytes are, respectively, controlled by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, determination of the ratio of these cells might allow a quantitative evaluation of their correlation with Yin and Yang [16,21,26,27]. Moreover, like granulocytes, the Natural Killer (NK)-cells that attack malignant cells are also controlled by the sympathetic nervous system. Thus, stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system is said to increase their numbers. In addition, the release of cytotoxic substances by NK-cells is presumably under the control of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Table 4 shows Yin-Yang correspondences of the autonomic nervous system.

Table 4.

Correspondence of Yin/Yang with the autonomic nervous system

| Sympathetic nerve ↑ | Parasympathetic nerve ↑ | |

|---|---|---|

| Classification as Yin or Yang | Yang | Yin |

| ↑ | ↓ | |

| ↓ | ↑ | |

|

Increased cell numbers | Hyperactivity |

| Hyperactivity | Increased cell numbers | |

| Time | Day | Night |

| Treatment | Yang tonic(Qi tonic) | Yin tonic(Blood tonic) |

We hypothesized that, if cancer patients in whom Yin and Yang are deficient were treated by Yang and Qi tonics during the day, NK-cell numbers would increase as a result of sympathetic activation.

Therefore, the parasympathetic nervous system would be expected to become more dominant as the day progressed leading to increased NK-cell activity towards night. The Chinese medical concept of chronotherapy can explain this switch from Yang to Yin.

Fig. 5 shows preparations that have been demonstrated to be effective in cancer patients. First, stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system with a Qi tonifying formula based on Astragalus membranaceus (Huang qi) leads to an increase in cAMP [19], inducing a rise in NK-cell numbers. This Qi tonifying formula contains the spleen strengthening herbs Panax ginseng (Ren shen), Atractylodes macrocephalax (Bai zhu) and Poria cocos (Fu ling) which all stimulate diuresis and excretion, as welt as Glycyrrhiza uralensis (Gan cao) actions controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system. Hence this refers to a yin effect within the yang [7,23,30]. As this Qi tonifying formula increases NK-cell numbers, increased NK-cell activity as a result of the strengthening spleen effect of this formula would be expected to follow chronological principles. Moreover, Poria cocos and mushroom (basidiophore) are considered to have the same mechanism of action.

Fig. 5.

Consideration of traditional Chinese herbs

Various forms of Chinese medical treatment are as follows: reinforcing (supplementing treatment), reducing (removing treatment) and mediating (harmonizing treatment). Each form of treatment has its own optimal time period: i) reinforcing, between 9:00 and 15:00 [Tai Yang phase]; ii) mediating between 3:00 and 9:00 [Shao Yang phase]; and iii)reducing, from 15:00 to 21:00 [Yang Ming phase] [22,24].

Chronotherapeutic approaches of Chinese medicine attempt to achieve a balance between Yin and Yang. A practical application of this form of treatment is the increased number of NK-cells and suggested improvement in activation of these cells via the administration of Chinese herbal formulations at specific times and in specific arrangements. We herein propose a treatment plan combining a reducing-type treatment in the afternoon or at night with aggressive Western medical therapeutic approaches [18] (Fig. 6). In other words, we describe how integration of Chinese chronotherapy may lead to a normalization of biorhythms as an integrative part of cancer therapy. These preliminary results suggest that a further larger study is warranted. In the future, further basic studies and analyses of numerous previous cases in addition to prospective studies are required for chronotherapy to be used to fight cancer in the field of Chinese Medicine.

Fig. 6.

Chinese and Western chronotherapeutic concepts The following concepts apply to the understanding of chronotherapy in Chinese medicine. Prior to the application of western medical treatment during the “Tai Yang phase” from 09:00 to 15:00, replenishing spleen Qi will increase the number.of NK-cells, while in the “Yin phase” from 21:00 to 07:00 the administration of mushrooms etc. enhances NK-cell activity. Later, when the immune function has been boosted, radio-therapy or surgery may be performed during the reducing period of the “Yang Ming phase” between 15:00 and 21:00 and followed by treatment with anticancer agents like 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or folic acid (FA) during the night (the time of application may vary with the type of the anticancer agent), permitting the administration of combination therapy. Moreover, integration of Chinese chronotherapy should also be feasible postsurgically.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Professor A. Renwick for his excellent advice, which was most helpful in the preparation of this article.

Glossary

1) Zhou Yi, Tai Ji.

2) Yin and Yang.

3) Qi and Blood.

4) Channels and Collaterals.

5) Viscera and Bowels (Zang and Fu organs).

6) Pattern (Zheng).

7) Chinese Herbs.

N.B.; This glossary is quoted in part from [31] and some parts are modified by the authors.

1) Zhou Yi, Tai Ji

The “Zhou Yi” system, which was used to explain the origins of the universe, requires the existence of a single absolute presence designated “ONE”, centering on the unmoving northem star in the northern sky. Its surroundings are expressed by the chaos governed by the laws of changes, in other words “Tai Ji”. In the “Tai Ji” illustration, the interrelated movements of the sun, earth and moon generate the changes of Yin and Yang. The Yin-Yang concept is not based on two opposing forces, but rather a theory of changes in nature rooted in a single force that always returns to the “ONE”.

2) Yin and Yang

Yin and Yang were concepts originally described in ancient Chinese philosophy, originally being used to denote whether or not a place faced the sun. A place exposed to the sun is considered Yang, while one in the shade is thought of as Yin. The southern side of a mountain, for example, is Yang, while the northern side is Yin. Subsequently, the theory was refined through many centuries of practice and observation of every type of natural phenomenon occurring throughout life. Yin and Yang came to be viewed as two components which oppose each other and exist in all things. Furthermore, their interaction was considered to promote the occurrence, development, and transformation of all things. Consequently, Yin and Yang theory can be used as means of analyzing all natural phenomena. The “Zhou Yi,” an ancient philosophical work, draws from complicated natural and social phenomena the same two philosophical concepts, describes Yin and Yang as forming the basis of the “Dao” (the basic law of the natural world) of heaven and earth.

The transformation of Yin and Yang into each other is therefore considered a fundamental law of the universe.

The impact of Yin and Yang theory on the science of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has promoted the formation and development of TCM's own theoretical system. Eventually, Yin and Yang theory itself became an important part of basic TCM theory.

In terms of chronological patterns, day is Yang and night is Yin by nature, but both day and night can be further divided as follows: the period from dawn till noon is considered the Yang within Yang; the period from noon till dusk, the Yin within Yang; the period from dusk till midnight, the Yin within Yin; and the period from midnight till dawn, the Yang within Yin.

3) Qi and blood

The concept of Qi is based on the original ancient Chinese understanding of natural phenomena, in which it is defined as the most basic energy of which the world is comprised. According to this view, everything in the universe results from the movements and changes of Qi. This concept was introduced into TCM and became one of its characteristics.

Although Qi in the human body differs in classification and formation, generally speaking, it has only two sources. One is the innate vital substance one inherits from one's parents before birth. The other is the nutritive essence and “fresh air” (natural energy part of which is oxygen) one receives from air, water, and food that are provided by the external environment.

The functions of Qi.

i) Promoting Action.

ii) Warming Action.

iii) Defending Action.

iv) Consolidating and Governing Action.

v) Promoting Metabolism and Transformation.

In TCM, blood is seen as a red liquid rich in nutrition, circulating within the blood vessels. Hence, vessels are regarded as tubes through which blood flows. Blood has the functions of nourishing and moistening the whole body. It circulates constantly within the vessels, to the five viscera and six bowels in the interior, and to the skin, muscles, ten-dons and bones in the exterior, continuously providing nutrients to all tissues and organs so as to maintain their normal physiological functions.

4) Channels and collaterals

Channel, or “Jing” in Chinese, means route, and represents the main trunks running vertically in the system of channels and collaterals; while the collaterals, or “Luo” in Chinese, refers to a net, and represents the branches of a channel in the system.

TCM holds that the channels and collaterals are distributed over the entire body and are interlinked. In this manner, the superficial and interior, and upper and lower aspects of the human body are connected, and the body is seen as an organic whole.

The composition of the System for the Channels and Collaterals:

i) The regular channels

Twelve regular channels are described, three Yin channels and three Yang channels in both hands and feet. These are collectively referred as the Twelve Channels which also have collateral pathways.

ii) The extra channels

These can be classified into the reticular branch and superficial branch conduits that connect the Twelve Channels with external cutaneous areas “Fu(Bowels) and Head”.

iii) The divergent channels

These are the branches that derive from, enter, emerge from and join the twelve regular channels which in turn reach the deeper parts of the body through these branches. Most of the twelve divergent channels derive from the regular channels at the upper and lower extremities in the region of the elbows and knees and then enter the thoracic and abdominal cavities, where they connect to the Zang (viscera) organs to which they pertain.

The cyclical flow of Qi (The Channels mean the paths for flow of Qi):

i) Defensive Qi

The movement of the Defensive Qi is said to provide circulation between the Yang channels on the exterior and the inner organs “Zhang (viscera)” which have collaterals.

ii) Nutritive Qi

Nutritive Qi originates from the middle warmer and enters the channels by way of the lung. The movement of the Nutritive Qi is said to provide circulation between the Twelve Channels and the “Fu(Bowels) and Head” each of which also has collaterals.

cf.) The triple (upper, middle and lower) warmer is one of the six bowels.

This term is peculiar to TCM. TCM says that the middle warmer ferments water and food and transports and transforms food essence in order to produce vital energy and blood. This referring is to the functions of the spleen and stomach.

When speaking of Yin and Yang of the twelve channels, the three Yang channels of the hand and three Yang channels of the foot are classified as Yang Ming, Shao Yang or Tai Yang, while the three Yin channels of the hand and three Yin channels of the foot are classified as Tai Yin, Jue Yin or Shao Yin. The visceral name of each channel is determined by the organ to which it pertains. For example, the channel pertaining to the spleen is named the spleen channel of Foot Tai Yin.

5) Viscera and bowels (Zang and Fu organs)

In TCM, the internal organs of the human body are divided into two groups: the “five viscera” and “six bowels”. The five viscera comprise the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney and have the common characteristic of preserving vital substances. The six bowels consist of the gall-bladder, stomach, large intestine, small intestine, urinary bladder and “triple warmer;” this group of organs functions to transmit and digest water and food.

The spleen

TCM is worlds apart from Western medicine in its understanding of the spleen. According to TCM, the spleen lies in the middle warmer (the middle portion of the body cavity) and is the main organ of the digestive system. The organ is further divided into its Yin aspects (its material structure) and Yang aspects (its functions and heat-generating properties).

The Qi of the spleen simply refers to its function. In TCM literature, the term “the blood of the spleen” is uncommon. The main functions of the spleen are digestion and absorption of food and supply of nutrients to all tissues of the body.

Among the three Yin aspects (Tai Yin, Shao Yin and Jue Yin) the Tai Yin is the most important. The organ related to the Tai Yin is the spleen. Oriental medicine interprets the function of the spleen as improvement of the digestive functions through the actions of Qi and providing the energy for warming the body from the inside (middle warmer).

Chen Xiou-Yuang (a medical doctor in China: A.D. 1753-1823) once said: “The spleen is the most important of the three Yin. For this reason even in a state of Yin deficiency (lack of nutrients) it is essential to improve digestion and absorption (supplement the spleen Qi) and replenish the nutrition (Yin).”

In other words, this indicates the importance of initially supplementing Qi (spleen Qi supplementation), even in Yin deficiency.

6) Diagnostic pattern (Zheng)

Diagnosis of TCM syndrome. The set pattern of a patient's symptoms due to the relative activity of Yin and Yang (Qi and Blood, Viscera and Bowels etc.) that indicates the appropriate Oriental medical approach.

i) Deficiency of Yin pattern

Symptoms as feverish sensation in the forehead palms and soles, dry throat, night sweating, emaciation, red tongue with little fur, thready and rapid pulse.

ii) Deficiency of Yang pattern

Symptoms as intolerance of cold, cold limb, pale complexion, not thirsty, fatigue, loose stool, plump pale tongue, deep slow and feeble pulse.

iii) Deficiency of Qi pattern

Symptoms as listlessness, lassitude, shortness of breath, spontaneous perspiration, pale tongue and weak pulse.

iv) Fire due to Yin deficiency pattern

It is more feverish sensation than Deficiency of Yin pattern.

v) Deficiency of Qi and Yin pattern

It is mixed of Deficiency of Yin and Deficiency of Qi pattern.

vi) Deficiency of Yin and Yang pattern

It is mixed of Deficiency of Yin and Deficiency of Yang pattern.

7) Chinese herbs

i) Astragalus membranaceus (Huang qi).

ii) Cinnamomum cassia (Rou gui).

iii) Panax ginseng (Ren shen).

iv) Atractylodes macrocephala (Bai zhu).

v) Poria cocos (Fu ling).

vi) Glycyrrhiza uralensis (Gan cao).

vii) Ligusticum wallichii (Chan xiong).

viii) Angelica sinensis (Dang gui).

ix) Paeonia lactifiora (Bai shao yao).

x) Rehmannia glutinosa (Shu di huang).

xi) Ziziphus jujuba (Da zao).

xii) Zingiber officinale (Sheng jiang).

xiii) Citrus tangerina (Ju pi).

xiv) Cimicifuga foetida (Sheng ma).

xv) Bupleurum chinense (Chai hu).

xvi) Codonopsis pilosula (Dang shen).

8) Chinese medicinal formulas

i) Buzhong-yiqi-tang

Crude herb composition: Astragalus membranaceus. Cinnamomum cassia Panax ginseng. Atractylodes macrocephala Poria cocos Glycyrrhiza uralensis Ligusticum wallichii Angelica sinensis Paeonia lactiflora Rehmannia glutinosa

ii) Shiquan-dabu-tang

Crude herb composition: Astragalus membranaceus Ziziphus jujuba Zingiber officinale Panax ginseng Atractylodes macrocephala Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Citrus tangerina Cimicifuga foetida. Bupleurum chinense. Angelica sinensis.

References

- 1.Abo T, Kawamura T. Immunomodulation by the autonomic nervous system: therapeutic approach for cancer, collagen diseases, and inflammatory Bowel diseases. Ther Apheresis. 2002;6(5):348. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-0968.2002.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen SZ, Liu KT, Yu YN, Yu CR. Medical Books. Vol. 1. Fujian Science and Technology Press; Fujian, China: 1981. New proofreading Chen Xiouyuang; Shang hua lun qian zhu du fa; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou R. An outline of clinical traditional Chinese medicine. Publishing House of Midori-Shobo; Tokyo, Japan: 1988. pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.“Huang di nei jing Ling shu” zhu shi. Vol. 3. Publishing House of Shanghai Science and Technology Press; China: 1986. Compiled by Nanjing collage of Traditional Chinese Medicine; pp. 468–75. [Google Scholar]

- 5.“Huang di nei jing Su wen” zhu shi. Vol. 10. Publishing House of Shanghai Science and Technology Press; China: 1987. Compiled by Nanjing collage of Traditional Chinese Medicine; pp. 61–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cyong JC. Japanese-English dictionary of oriental medicine. Publishing House of Iseisha; Tokyo, Japan: 1993. p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dictionary of Chinese drugs. Shanghai Science and Technology Press; China: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estensen RD, Hill HR, Quie PG, Gogan N, Goldberg ND. Cyclic GMP and cell movement. Nature. 1973;245(5426):458–60. doi: 10.1038/245458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George WJ, Polusion JB, O'Toole AG, et al. Elevation of guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic phosphate in rat heart after perfusion with acetylcholine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;66:398–403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.2.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan AF. J Harbin Med Univ. 1975;1:133. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg ND, O'Dea RF, Haddox MK, Cyclic GMP. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1973;3:155–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haddox MK, Nicol SE, Goldberg ND. pH induced increase in cyclic GMP reactivity with cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;54(4):144–50. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)91148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He SX, Song KY, Su ZY. Chronotherapy and Chronopharmacotherapy. Tianjin Science and Technology Press; Tianjn, China: 1994. pp. 270–80. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honma M, Satoh T, Takezawa J, Ui M. An ultrasensitive method for the simultaneous determination of cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP in small-volume samples from blood and tissue. Biochem Med. 1977;18:257–73. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(77)90060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida H. A history of Chinese medical thought. University of Tokyo Press; Japan: 1992. pp. 124–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamura T, Toyabe S, Moroda T, Iiai T, Takahashi I, Iwanaga H, et al. Neonatal granulocytosis is a postpartum event which is seen in the liver as well as in the blood. Hepatology. 1997;26:1567–72. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v26.pm0009397999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.sKe SG. Nan fang yi hua. (Gan JG) Beijing Science and Technology Press; China: 1991. pp. 64–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levi F, et al. A phase I–II trial of 5-day continuous intravenous infusion of 5-fluorouracil delivered at circadian rhythm modulated rate in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Infus Chemother. 1995;5:153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li DX, et al. Effects of astragalus saponin 1 on cAMP and cGMP level in plasma and DNA synthesis in regenerating liver Nanjing Medical College. J Pharm. 1984;19(8):619–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li YL, Ke QG. Shiyoung zuijia shijian zhenjiu jinggyi. Beijing Xueyuan Press; China: 1994. pp. 77–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madden KS, Livnat S. In Psychoneuroimmunology. Academic Press; New York: 1991. p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyashita I, Itou M. “Zhou Yi and traditional Chinese medicine” Ido-no-Nippon-Sha; Yokosuka, Japan; 1992. pp. 3–63. translater. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saiki I. Cancer and tonic prescriptions. Jpn J Orient Med. 2000;50(3):808–17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sono K. Shang Han Run that I watched from east and west medicine. Publishing House of Nanzando; Tokyo, Japan: 2002. p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xuan MY, et al. A study report of Hiroshima electricity and autoindustry junior college. 24. Hiroshima, Japan: 1991. Planning for computer program on Ziwuliuzhu Nazifa method in Chinese medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki S, Toyabe S, Moroda T, Tukahara A, Iiai T, Minagawa M, et al. Circadian rhythm of leukocytes and lymphocyte subsets and its possible correlation with the function of autonomic nervous system. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;10:500–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4411460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toyabe S, Iiai T, Fukuda M, Kawamura T, Suzuki S, Uchiyama M, et al. Idetification of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on lymphocytes in periphery as well as thymus in mice. Immunology. 1997;92:201–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamauti H, Uemura S, Kokubu M. (Translator) A guide to immunology of traditional Chinese medicine. Oriental Science Press; Japan: 1993. p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L. “Zhou Yi and traditional Chinese medicine”. Beijing Science and Technology Press; China: 1990. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zang Xi-chun. “Yi Xue Zhong Zhong Can Xi Lu”. Hebei Science and Technology Press; China: 1991. p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang EQ, et al. A practical English-Chinese library of traditional Chinese medicine basic theory of traditional Chinese medicine(I) Publishing House of Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 1990 Chapter.2, pp 38–53 Chapter 3, pp. 70–1, pp. 88–93, pp. 124–9 Chapter 4, pp. 164–73, pp. 184–91 Chapter 5, pp. 208–15. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang EQ, et al. A practical English–Chinese library of traditional Chinese medicine-diagnostic of traditional Chinese medicine. Publishing House of Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 1988:294–301. Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]