Abstract

The syntheses and structures of three new coordinatively unsaturated, monomeric, square pyramidal thiolate-ligated Fe(III) complexes are described, [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)]+ (1), [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)(py)]1- (3), and [FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15). The anionic bis-carboxamide, tris-thiolate N2S3 coordination sphere of 15 is potentially similar to that of the yet-to-be characterized unmodified form of NHase. Comparison of the magnetic and reactivity properties of these reveals how anionic charge build-up (from cationic 1 to anionic 3 and dianionic 15) and spin-state influence apical ligand affinity. For all of the ligand-field combinations examined, an intermediate S= 3/2 spin-state was shown to be favored by a strong N2S2 basal plane ligand-field, and this was found to reduce the affinity for apical ligands, even when they are built-in. This is in contrast to the post-translationaly modified NHase active site, which is low-spin, and displays a higher affinity for apical ligands. Cationic 1 and its reduced FeII precursor are shown to bind NO and CO, respectively, to afford [FeIII((tame-N3)S2Me(NO)]+ (18, νNO= 1865 cm-1), an analogue of NO-inactivated NHase, and [FeII((tame-N3)S2Me)(CO)] (16; νCO stretch (1895 cm-1). Anions (N3-, CN-) are shown to be unreactive towards 1, 3 and 15, and neutral ligands unreactive towards 3 and 15, even when present in 100-fold excess, and at low—temperatures. The curtailed reactivity of 15, an analogue of the unmodified form of NHase, and its apical-oxygenated S= 3/2 derivative [FeIII((tame—N2SO2)S2Me2)]2- (20) suggests that regioselective post—translational oxygenation of the basal plane NHase cysteinate sulfurs plays an important role in promoting substrate binding. This is supported by previously reported theoretical (DFT) calculations.1

Introduction

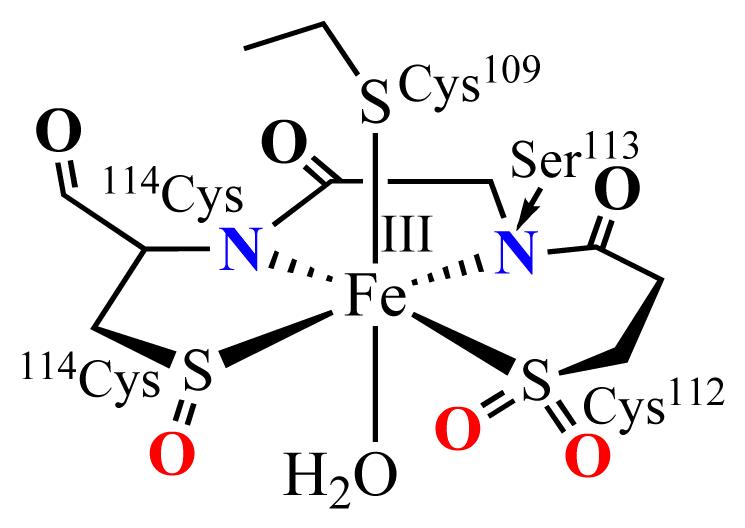

Nitrile hydratases are non-heme iron enzymes that catalyze the enantioselective hydrolysis of nitriles to amides.2-6 The active site of NHases are unusual and differ dramatically from the majority of non-heme iron enzymes, in that they contain three cysteinate ligands and two deprotonated peptide amides,7,8 as opposed to the more typical N/O (N2HisOAsp,Glu facial triad) ligand environment.9-12 The more covalent and electron-rich ligand environment of NHase stabilizes low-spin (S= ½) iron in the +3 oxidation state.13,14 Two of the cysteinates are oxidized (post-translationally modified), one to a sulfenic acid (114Cys—S—OH),1 or possibly 114Cys—SO2-,15 and the other to a sulfinate (112Cys—SO2-).16 Our group has been attempting to determine how the unusual active site structure of NHase contributes to its function.1,13,14,17-21 For example, why does nature incorporate cysteinates, only to modify them? Is there a correlation between structure, spin-state and reactivity? What ligand environment is necessary for the stabilization of a low spin-state? The low spin-state of NHase is unusual given that π-donor ligands, such as RS-, usually favor a high-spin state.20 The majority of non-heme iron enzymes are high-spin,9,11 and porphyrin ligands were originally thought to be necessary to stabilize low-spin Fe(III).22 We and others have shown that the magnetic and spectroscopic properties of NHase can be accurately reproduced by six—coordinate Fe(III) model complexes,23-28 containing two cis—thiolates, imines and in some cases an open binding site trans to one of the thiolates.13,18,21,25 Detailed spectroscopic and theoretical studies involving some of these compounds have shown that anisotropy in the available π—symmetry metal orbitals contribute to the stabilization of a low—spin state,20 as does the highly covalent nature of the Fe—S bonds.

The mechanism by which NHase operates has yet to be elucidated. It has been proposed that the iron site serves as either a hydroxide source, or as a Lewis—acidic site to which nitriles coordinate.4,8,16,26,29-36 In either case, the Fe3+ ion must be capable of binding H2O, OH-, or MeCN. The tetraanionic [N2amideScys(cysSOH)(cysSO2)]4- ligand environment of NHase would, however, be expected to decrease the metal ion Lewis acidity and affinity for substrates. The oxygen atoms cysSOH and cysSO2-, incorporated during post-translational modification, may help to offset this charge build-up.36 Insight regarding the functional role of the oxidized cysteinates would require isolation of the unmodified form of NHase. However, this form of the enzyme has yet to be characterized in its metal-containing form. An unmodified apo-form of Co-type NHase has been structurally characterized, and shown to contain a cysteine-disulfide in place of the post-translationaly oxidized sulfurs.37 However in the absence of a metal ion, this structure does not indicate how the absence of oxygens might influence the electronic and reactivity properties important to function.

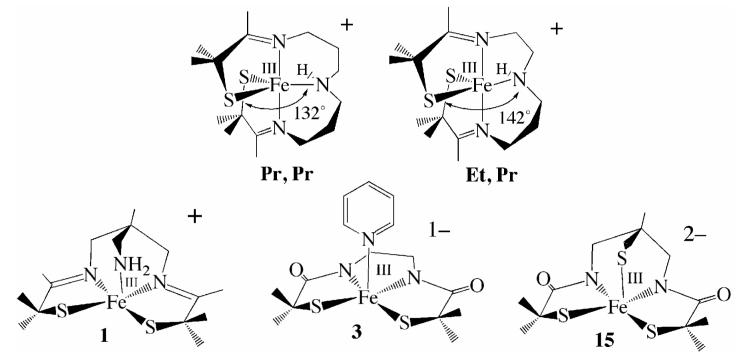

Previous NHase analogues synthesized by our group include five—coordinate [FeIII((Pr,Pr—N3)S2Me2)]+ (Pr,Pr in Scheme 1) and [FeIII((Et,Pr—N3)S2Me2)]+ (Et,Pr in Scheme 1) which bind NO and reversibly bind azide,38 but do not readily bind nitriles at ambient temperature.18 Reactivity of these models was shown to correlate with spin—state.18,21,38,39 Ligand constraints and metal ion accessibility may also limit reactivity, given that the pentadentate Pr,Pr and Et,Pr ligands favor trigonal bipyramidal over octahedral geometries.13,14 These ligands also incorporate a less anionic ligand set relative to that found at the active site of NHase. This prompted us to look into the design of models with less constraining ligands, a more open face, and deprotonated carboxamides in place of imines. Herein, we describe and compare the structural and reactivity properties of three new square pyramidal thiolate-ligated Fe(III) complexes, with ligands that favor the orthogonal angles required for substrate binding, and in one case an anionic bis-carboxamide, tris-thiolate N2S3 coordination sphere matching that of the yet-to-be characterized unmodified form of NHase. In order to determine how anionic charge build-up influences substrate affinity, structurally—related cationic, anionic, and dianionic complexes are compared.

Scheme 1.

Results and Discussion

Syntheses of Thiolate-Ligated Model Complexes

The synthesis of transition-metal complexes containing an open-coordination site usually requires the use of steric bulk, non—coordinating solvents, and the strict avoidance of potentially coordinating counterions.40-45 Isolation of coordinatively unsaturated monomeric complexes is especially difficult when thiolates are included in the coordination sphere, since metal thiolates are prone to oligomerization.46-48 When mimicking a metalloenzyme active site, multidentate ligands are generally required in order to maintain a somewhat rigid structure, since the biologically important first-row transition-metal ions tend to be substitution labile.22,49 Previously we, and others, showed that gem dimethyls adjacent to the sulfur can prevent dimerization of iron thiolates.18,21,50-52 And more recently we showed that thiolate ligands reduce metal ion Lewis acidity relative to alkoxides and amines, and have a strong trans influence thereby helping to maintain an open coordination site.53 The previously reported tame-N3 (1,1,1-triaminoethane)54,55 ligand was used in this study as a scaffold for the new complexes, since it favors a more open, less constrained, square pyramidal or octahedral geometry as illustrated in Scheme 1. Details regarding the synthesis of the new tris-thiol, bis-carboxamide tame—(NH)2(SH)3 (14) ligand, as well as the synthesis and crystallographic characterization of square pyramidal [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)](PF6)•PhCN (1), (Me4N)[FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)(Py)]•2MeOH (3), (NMe4)2[FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]•MeCN (15), and dimeric (NMe4)2[FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)]2•2MeOH (2) are provided in the supplemental material.

Syntheses and Structure of Square Pyramidal [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)]+ (1), [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)]22- (2), [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)(py)]1- (3), and [FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15)

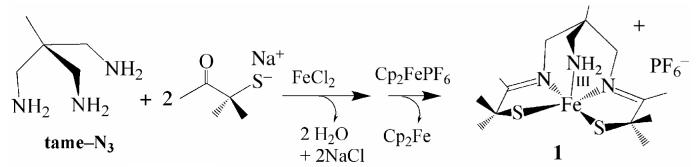

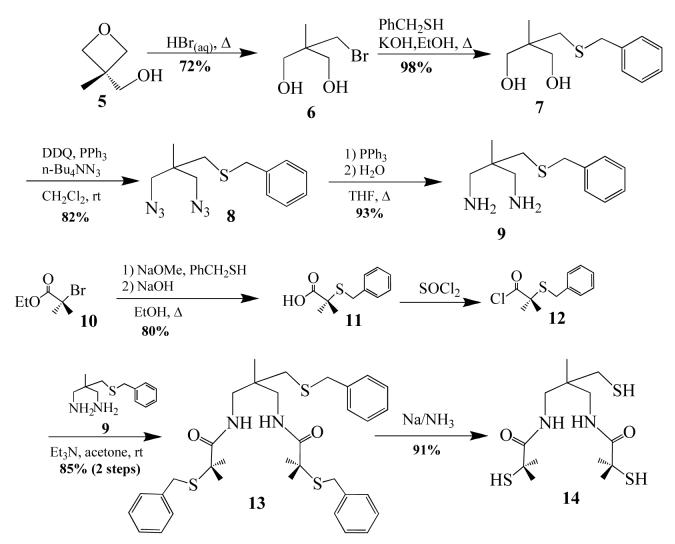

Imine- ligated [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)](PF6)•PhCN (1) was synthesized under anaerobic conditions via an Fe2+—templated, Schiff—base condensation reaction between tame—N3 and two equiv of deprotonated 3-methyl-3mercapto-2-butanone,24 followed by oxidation with Cp2Fe+ in benzonitrile (Scheme 2). The carboxamide-containing ligand N,N’-1,2-ethanediylbis[2-mercapto-2-methyl-propanamide] (Et—(NH)2(SH)2Me2) was synthesized as described elsewhere,56 and deprotonated in the presence of (NMe4)[FeCl4] to initially afford a thiolate—bridged dimeric complex (NMe4)2[FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)]2•2MeOH (2 Scheme 3, Figure 2), which is readily cleaved into monomers by coordinating solvents. Addition of excess pyridine to dimeric 2 in MeOH (2:1 MeOH/pyridine) results in the cleavage of the bridging Fe(1)-S(3) and Fe(2)—S(1) bonds to afford monomeric, monoanionic pyridine-ligated (Me4N)[FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)(Py)]•2MeOH (3; Scheme 3, Figure 3). The protonated tris—thiol bis—carboxamide ligand tame—(NH)2(SH)3 (14) was synthesized in excellent yields according to the six step convergent synthesis outlined in Scheme 4. This involves the addition of HBr(aq) to 3-methyl-oxetan-3-yl-methanol (5) to afford diol 6 in 72% yield, followed by SN2 displacement of the bromine upon addition of deprotonated benzyl mercaptan to afford 7 in 98% yield. Conversion of diol 7 to diazide 8 was achieved via the addition of DDQ/PPh3/n-Bu4NN3. Reduction of 8 was achieved using PPh3 to afford diamine 9 in 93% yield. This fragment is an analogue of the tame-N3 ligand used in the synthesis of 1 (Scheme 2). To incorporate two more aliphatic thiolates into 14, a second fragment (12) was synthesized, via the addition of benzyl mercaptan to ethyl 2-bromo-2-methyl propionate (10) in the presence of base to initially afford 11 (in 80% yield), which was converted to the chloride derivative 12, via the addition of thionyl chloride. Addition of tame-derived 9 to 12 afforded benzyl-protected tris-thiolate 13. Deprotection of the sulfurs using Na/NH3 followed by the addition of HCl afforded tame—(NH)2(SH)3 (14) (ESI-MS= 339.3, Figure S—8). Evidence for the presence of the free thiols was obtained by 1H-NMR (Figure S-5 and Figure S-6) and IR spectroscopy (νSH= 2544 cm-1, Figure S-7). The corresponding tris-thiolate ligated Fe3+ complex [FeIII(tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15), was synthesized via the addition of 5 equiv of NaOMe to a mixture of tame—(NH)2(SH)3 (14) and (Me4N)FeCl4 in MeOH at −35 °C.

Scheme 2.

Scheme 3.

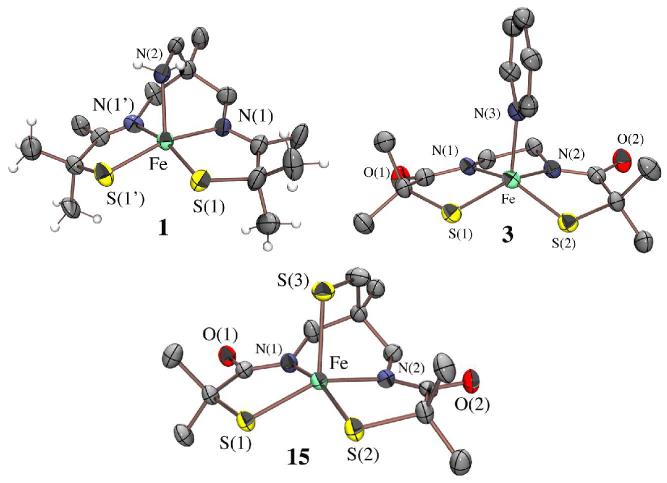

Figure 2.

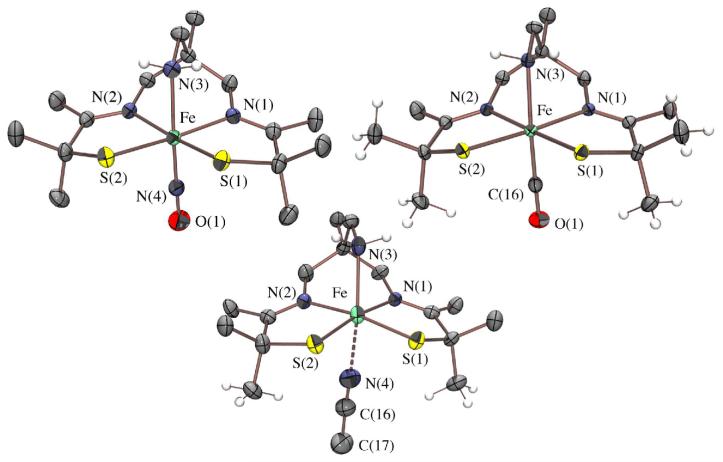

ORTEP of the anion of dimeric (NMe4)2[FeIII((Et—N2)S2Me2)]2•2MeOH (2) showing atom labeling scheme. All hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

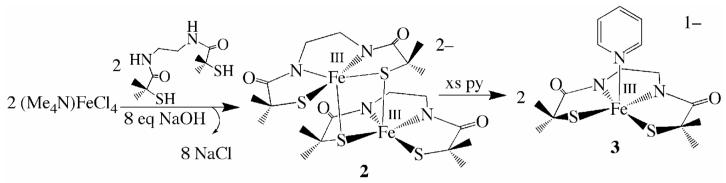

Figure 3.

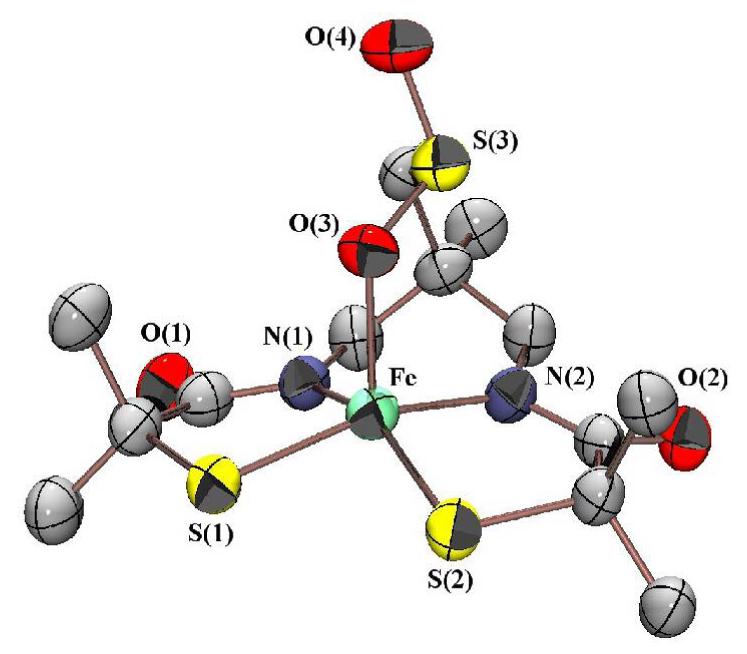

ORTEP of the cation of [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)](PF6)•PhCN (1), and the anions of (Me4N)[FeIII((Et—N2)S2Me2)(Py)]•2MeOH (3) and (NMe4)2[FeIII((tameN2S)S2Me2)]•MeCN (15), showing 50% ellipsoids and atom labeling scheme. All hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

Scheme 4.

X-ray quality crystals of 1, dimeric 2, and monomeric 3, were obtained by layering Et2O onto concentrated PhCN, MeOH, and 2:1 MeOH/pyridine solutions, respectively, and cooling to −35 °C. X-ray quality crystals of (NMe4)2[FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]•MeCN (15) were obtained by layered diffusion of Et2O into a MeCN solution at −35 °C. Crystallographic data collection and refinement parameters are contained in Table S—1, and metrical parameters for complexes 1-3 are compared in Table S—2. As shown in the ORTEP diagram of Figure 3, monomeric 1 contains a five-coordinate Fe3+ ion in a square pyramidal geometry (τ = 0.0),57 with two cis—thiolates and two cis—imine nitrogens (N(1) and N(1′)) in the basal plane, and an apical primary amine nitrogen (N(2)). The square-pyramidal Fe3+ ions of 3 and 15, on the other hand, contain two cis carboxamides (N(1) and N(2)) in place of 1′s imines in combination with two cis thiolates in the N2S2 basal plane, and either an apical pyridine (3) or thiolate (15) in place of the primary amine (1). The Fe3+ ion of 1 sits 0.293 Å above the mean basal N2S2 plane, and on a crystallographic mirror plane rendering S(1) and S(1′), as well as N(1) and N(1′) equivalent. The Fe3+ ion of 3 and 15, on the other hand, is pulled further (0.404 Å with 3, and 0.408 Å with 15) above the mean basal N2S2 plane, indicating that the metal ion has a higher affinity for apical thiolate and pyridine ligands. The N3S2 and N2S3 coordination spheres of 3 (τ = 0.090) and 15 (τ = 0.16) deviate only slightly from ideal square pyramidal (τ = 0.0).57 The tris-thiolate, bis-carboxamide [N2S3]5- coordination-sphere of 15 is potentially similar to that of the yet-to-be characterized unmodified form of NHase. The Fe3+ ions of 2 (Figure 2) sit 0.449 Å and 0.447 Å above the mean N2S2 basal planes, in an N2S3 coordination sphere that deviates only slightly (τ = 0.011 Å) from ideal square pyramidal. The basal plane Fe—S(1) distance of 1 (2.189(2) Å; Table S-2) is noticeably shorter than those of 3 (2.21(1) Å) and 15 (2.22(2) Å), reflecting the stronger trans influence of carboxamide versus imine ligands. This bond is considerably shorter than the sum of the covalent radii (2.27Å)58 indicating that the Fe—S bonds of 1 possess partial double bond (or significant ionic) character. The Fe—S bonds of dimeric 2 are differentiated by the distinct roles played by the sulfurs, as terminal (S(2); Fe(1)-S(2)= 2.199(2) Å) versus bridging (S(1); Fe(1)-S(1)= 2.251(2) Å) ligands.

The apical Fe—X (X= primary amine (1), pyridine (3), and thiolate (2 and 15)) bonds are considerably longer than typical bonds of this type, and/or the corresponding basal plane bonds. For example, Fe—N(amine) bonds usually fall in the range: 2.00-2.06 Å,17,21,59-62 whereas the Fe—N(2) bond of 1 is longer (2.132(6)Å). Iron-pyridine Fe—N distances usually fall in the range of 1.92 – 2.14,59,63-68 whereas that of 3 (Fe—N(3)) is longer (2.167(3) Å. The longer apical pyridine Fe-N(3) distance of 3 versus the apical amine Fe-N(2) distance of 1 reflects the stronger basal ligand-field imposed by the carboxamides, as well as the decreased Lewis acidity of the metal ion caused by the replacement of two neutral imines with two anionic deprotonated carboxamides. It is also possible that ligand constraints compress the apical amine distance. Pyridine Fe—N bonds are usually shorter, rather than longer, than amine Fe—N bonds. The apical Fe—S bonds in 2 (Fe—S(3)= 2.446(2) Å) and 15 (2.4058(7) Å) are considerably longer than the typical range (2.14 – 2.25 Å (low-spin); 2.30 – 2.37 Å high-spin)17,23,24,38,59-62,67-70 reflecting a large differential between the apical and basal ligand-fields. This is supported by the magnetic data (vide infra), and indicates that in the case of 2 the thiolate bridge should readily cleave. Both the strong basal ligand-field, and progressive negative charge build-up (in going from cationic 1, to monanionic 3, and dianionic 15) appear, therefore, to reduce the metal ion Lewis acidity of these square pyramidal complexes, and their affinity for built-in apical ligands. This is not without precedent given that deprotonated carboxamide ligands have been previously shown to favor lower coordination numbers.71 In addition, we recently showed that, when compared to alkoxides or amines, thiolate ligands favor lower coordination numbers.53

Electronic and Magnetic Properties

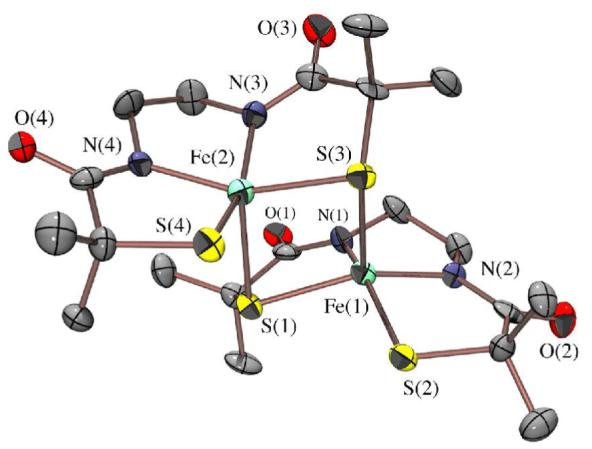

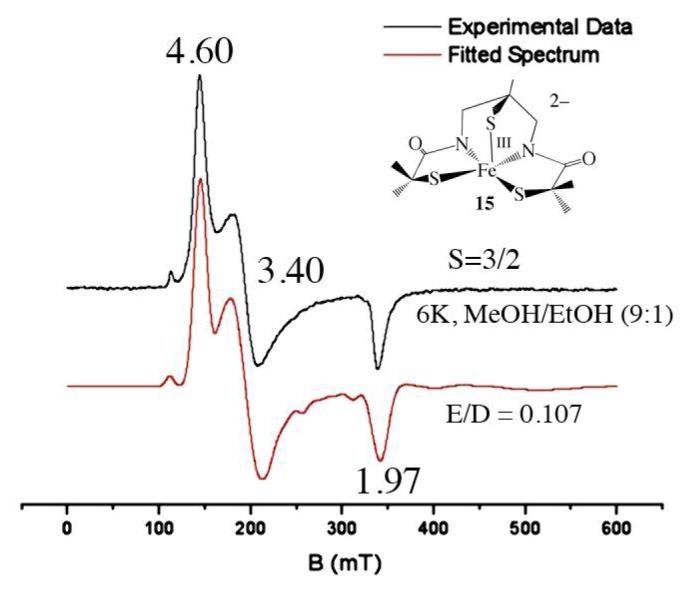

As illustrated in Table 1, the electronic and magnetic properties of the square pyramidal compounds described herein differ notably from those of low-spin (S=1/2) NHase, and low-spin synthetic analogues described previously by our group.1,13,14,17,18,20,21,23,59 All of the compounds described herein are intermediate—spin S=3/2, and solutions appear various shades of red, whereas all of the low-spin complexes in Table 1 appear green. One can attribute these differences to changes in coordination number and the resulting decrease in the separation between energy states. The electronic spectrum of dimeric 2 is solvent-dependent (Table 1). Coordinating solvents appear to cleave the dimer to afford solvent-bound five-coordinate derivatives, based on a similarity of their spectra to that of pyridine-bound 3. Six-equivalents of pyridine are required to completely convert 2 to 3 in CH2Cl2 (Figure S-12). In MeOH, the two Fe3+ ions of 2 behave independently, showing no signs of antiferromagnetic coupling, as indicated by the solution magnetic moment (∝eff(298 K)/Fe3+ = 4.01 ∝B), and EPR spectrum (g= 4.35, 2.00, E/D= 0.092, Figure S-14), which are consistent with a pure S= 3/2 spin-state over all temperatures (5 – 298 K) examined. Monomeric 3 and 15 are also intermediate—spin S= 3/2, both in solution (∝eff(3, 298 K, MeOH) = 3.72 ∝B; ∝eff(15, 298 K, MeOH) = 3.99 ∝B), and in the solid state (Figure 4), over all temperatures (4 – 300 K) examined. Fits to the low temperature EPR data of 3 (Figure S—13) and 15 (Figure 5) are consistent with an S=3/2 ground state, and Fe3+ in ∼axial (E/D 0.065), and slightly rhombic (E/D = 0.107) environments, respectively. Monomeric [FeIII(tame—N3)S2Me2)]+ (1) is also intermediate—spin (S= 3/2) both in the solid state over the temperature range 7–300 K (∝eff = 3.96 ∝B; Figure S-15), and in MeOH solution (∝eff = 3.74 ∝B) at ambient temperatures. Fits to the low temperature (7 K) EPR data for 1 in non-coordinating solvents (e.g., 2-Me-THF) are consistent with Fe3+ in a rhombically distorted environment (E/D = 0.185) and a pure S=3/2 ground state (g= 4.88, 2.60, 1.71; Figure S-16). The only exception to these trends occurs in coordinating solvents at extremely low temperatures (7 K), where 1 is present as a mixture of S=1/2 and S= 3/2 spin-states (g= 5.01, 4.25; and g= 2.25, 2.17, 1.95; Figure S—17). This would suggest that coordinating solvents bind to 1 at extremely low temperatures, where it would be entropically favored. The majority of characterized six-coordinate FeIII—thiolates are low-spin S= ½, whereas five-coordinate FeIII—thiolates, tend to display temperature-dependent magnetic properties highly dependent upon geometry, and S—Fe—S bond angles.18,21,38,39 Solvent binding would raise the energy of the half-occupied dz2 orbital of intermediate-spin 1, causing the electron to drop into the t2g set of orbitals resulting in an S= 3/2 → S= 1/2 spin-state change. In fact, when 1 is re-crystallized from MeCN, a co-crystallized MeCN points towards the vacant site, and appears to perturb the coordination environment at the Fe center, as determined by X-ray crystallography (vide infra), however the complex remains intermediate-spin at temperatures above 7 K.

Table 1.

Electronic Absorption and Magnetic Properties of S= 3/2 Square Pyramidal FeIII-Thiolates versus S= ½ Complexes and NHase.

| Compound | Color | λmax(ε)* (nm) | X-Band EPR (g-values)** |

|---|---|---|---|

| [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)]+ (1) | red | 400(3380), 540(1300) | 4.88, 2.60, 1.71 |

| [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)]22- (2)) | red | 465(6000)& | 4.35, 2.00 |

| 420(5700), 465(6000)& | |||

| 320(9200), 497(3200) $ | |||

| [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)(Py)]1- (3) | red/brown | 415(2600), 494(4800)# | 4.45, 1.97 |

| 424(2600), 487(4800)$ | |||

| [FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15) | orange | 471(3250), 433(2540, sh) | 4.60, 3.40, 1.97 |

| [FeIII(ADIT)2]+ | green | 416(4200), 718(1400) | 2.19, 2.13, 2.01 |

| [FeIII(DITpy)2]+ | green | 784(1300) | 2.16, 2.10, 2.02 |

| [FeIII(DITIm)2]+ | green | 802(1300) | 2.19, 2.15, 2.01 |

| [FeIII((Pr,Pr)—N3S2Me2)(N3)]+ | green | 460(220), 708(1600) | 2.23, 2.16, 1.99 |

| [FeIII((Et,Pr)— N3S2Me2)(MeCN)]+ |

green | 454(∼1100), 833(∼1000) | 2.17, 2.14, 2.01 |

| NHase enzyme | green | 710(∼1200) | 2.27, 2.14, 1.97 |

In MeCN unless otherwise indicated.

In MeOH/EtOH (9:1) glass unless otherwise indicated

Spectrum recorded in MeOH solution.

Spectrum recorded in pyridine solution.

Spectrum recorded in CH2Cl2 solution.

Figure 4.

Inverse molar magnetic susceptibility 1/χm vs temperature (T) plot for (Me4N)[FeIII((Et—N2)S2Me2)(Py)]•2MeOH (3) and (NMe4)2[FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]•MeCN (15) each fit to an S = 3/2 spin-state with Curie constants 2.05 (3) and 1.91 (15).

Figure 5.

Low temperature (7 K) X-band EPR spectrum (black) of (NMe4)2[FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]•MeCN (15) in MeOH/EtOH (9:1) glass, fitted (red) to E/D = 0.107.

Pure intermediate (S = 3/2) spin-states of iron(III) are rare, and predominantly seen when Fe3+ is in an tetragonally-distorted environment in which the apical and equatorial ligand fields are dramatically different.72-75 Dithiolenes, tetra-aza- macrocycles, and carboxamide ligands, for example, have all been shown to favor these spin-states.76-79 The relative stabilities of the S= 3/2 and S=1/2 electronic configurations depends on the separation between the dxy and dz2 orbitals, ΔE(t2g/eg*) (Figure S—18). Extensive π-bonding with the thiolates and/or carboxamides in the xy plane of 1, 3, and 15 would push the dxy orbital up in energy towards the dz2, decreasing ΔE and thereby favoring an S= 3/2 ground state with a half occupied dz2 orbital. The half-occupied dz2 orbital of an S= 3/2 spin-system would decrease the open binding site’s Lewis acidity, relative to that of a low (S=1/2) spin system (Figure S—18) with its empty dz2 orbital. This could have important consequences when it comes to “substrate” binding (vide infra).

Redox Properties

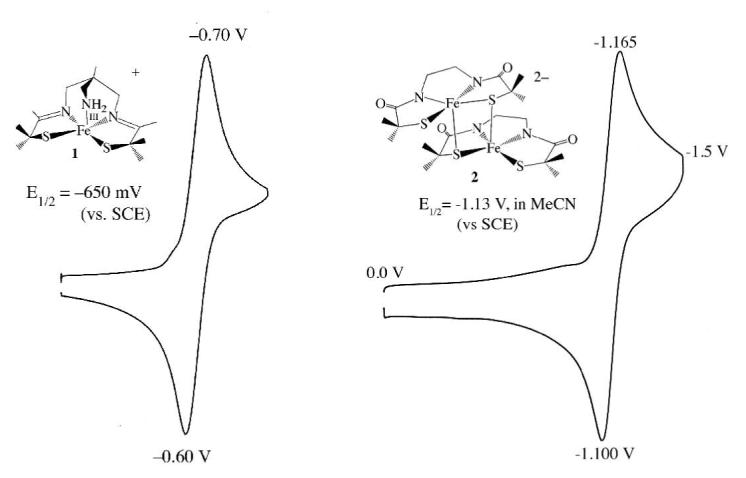

As shown by the negative redox potentials of Table 2, and the cyclic voltammograms of Figures 6, and S—19, the ligands described in this study stabilize iron in the +3 oxidation state, adhering to trends established for thiolate/carboxamide ligatd iron complexes. 13,14,23,27,59,67,68,80 Redox potentials shift in a negative direction as anionic carboxamides are incorporated in place of 1′s neutral imines (Table 2),81,82 as well as when the neutral apical amine of 3 is replaced by an anionic apical thiolate in 15. In fact, the 5- charge of 15′s [N2S3]5- ligand creates such an electron-rich environment for the Fe3+ ion, that no reduction wave is observed in the window +1.0 V → -1.8 V (vs SCE). This shows that the +2 oxidation state is inaccessible at reasonable potentials, and that the energy of the redox active orbital is raised dramatically when Fe3+ is place in an environment identical to that of unmodified NHase. The inaccessibility of the +2 oxidation state is important for the prevention of undesirable Fenton-type side—reactions.83

Table 2.

Redox Potential Dependence on Ligand Environment and Molecular Charge.

| Compound | Reduction Potential (vs SCE) |

|---|---|

| [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)]+ (1) | −650 mV |

| [FeIII(DITIm)2]+ | −680 mV |

| [FeIII(DITpy)2]+ | −930 mV |

| [FeIII(ADIT)2]+ | −1002 mV |

| [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)]22- (2) | −1130 mV |

| [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)(Py)]1- (3) | −1340 mV |

| [FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15) | < -1800 mV |

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammogram of [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)](PF6)•PhCN (1) and (NMe4)2[FeIII((Et—N2)S2Me2)]2•2MeOH (2), both in MeCN at 298 K (0.1 M (Bu4N)PF6, glassy carbon electrode, 150 mV/sec scan rate). Peak potentials versus SCE indicated.

Reactivity of Five-coordinate [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)]+ (1), [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)(Py)]1- (3), and [FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15), and dimeric [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)]22- (2)

Although dimeric [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)]22- (2) undergoes bridge cleavage reactions with neutral σ-donors such as pyridine, the resulting S= 3/2 anionic compound [FeIII(Et—N2S2Me2)(Py)]1- (3) remains five-coordinate even in neat pyridine. Dianionic S= 3/2 [FeIII(tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15) displays a similar lack of affinity for additional ligands. Even when added in excess (>100 eq) and at low temperatures (−78 °C), anionic (N3-, CN-), neutral (Py, CO) and/or σ-donor ligands (MeCN) show no signs of binding to 3 or 15, as determined by electronic absorption spectroscopy. Nitric oxide reacts with 15, however the product obtained in this reaction proved to be too unstable to isolate. Cationic S=3/2 [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)]+ (1) is only slightly more reactive than anionic 3 and 15 suggesting that overall molecular charge (1- vs 1+), and the weaker ligand field (imines in 1 versus carboxamides in 3 and 15), only slightly influences reactivity properties. Cationic 1 will only bind π—acid ligands such as NO at ambient temperature, and not anions such as CN- or N3-. Neutral ligands (such as MeOH) bind to cationic 1 only at extremely low (7 K) temperatures (vide supra). At 7 K anionic 3 and 15, on the other hand, show no signs (by EPR) of binding neutral ligands. Although oxidized 1 does not bind CO, its neutral reduced Fe(II) precursor can be trapped with CO(g), affording [FeII((tame-N3)S2Me)(CO)] (16). The extremely low νCO stretch (1895 cm-1 (16; Figure S—20) vs typical FeII—CO range νCO = 1929–1969 cm-1) indicates that the Fe2+ ion of 16 is fairly electron-rich. Carbonyl-ligated Fe2+ compounds are rare, and typically quite labile.24,84 For example, previously reported [FeII((Pr,Pr)—N3S2Me2)(CO)] (17, νCO = 1929 cm-1) readily dissociates CO at temperatures above 0°C.24 Carbonyl-ligated 16 (Figure 7) CO-is considerably more stable than 17, most likely because CO binds trans to an amine in 16, as opposed to a thiolate in 17. Quantitative addition of NO(g) to oxidized 1 affords [FeIII((tame-N3)S2Me)(NO)]+ (18), an analogue of the NO—inhibited form of NHase. Complex 18 (Figure 7) displays an νNO stretch (1865 cm-1; Figure S—21) close to that of NHase (νNO = 1853 cm-1), and is diamagnetic (Figure S—22), indicating that NO—binding induces a spin—state change at the metal S= 3/2 → S= 1/2. The mean Fe—S distance in 18 (2.254(4) Å) is 0.068 Å longer than in 1, and 0.024 Å shorter than in reduced carbonyl-bound 16 (2.278(1) Å; Table S-3), indicating that the most appropriate formal electronic description lies somewhere between Fe(III)—NO• and Fe(II)—NO+. Metrical parameters for 16 are compared with that of 18 in supplemental Table S-3.

Figure 7.

ORTEP of reduced [FeII((tame—N3)S2Me2)(CO)]•MeCN (16), the cations of [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)(NO)](PF6) (18) and [FeIII((tame—N3)S2Me2)(MeCN)](PF6)•MeCN (19) showing 50% ellipsoids and atom labeling scheme, as well as the weakly interacting MeCN (Fe—N(4)= 2.63 Å) in 19.

Based on the appearance of a new low—spin species in the EPR spectrum (Figure S—17), cationic 1 does appear to bind neutral σ—donors such as MeOH, but only at extremely low temperatures (7 K). When MeCN is used as the solvent for recrystallization of 1, in place of PhCN, a co-crystallized MeCN points towards the vacant site of [FeIII(tame-N3)S2Me2)(MeCN)]+ (19) (Figure 7). Although this interaction is weak (Fe—N(4) = 2.63 Å) it does appear to elongate the apical Fe—N(3) bond (by 0.056 Å in 19 relative to 1; supplemental Tables S-2 and S-3), and causes the Fe3+ ion to move 0.147 Å closer to the N2S2 basal plane (from 0.293 Å in 1 to 0.147 Å in 19), away from apical amine N(3), towards the acetonitrile (N(4)). The νCN (MeCN) value of 2254 cm-1 is close to that of free MeCN, and there is no significant increase in the nitrile C(16)—N(4) bond length in 19 (1.159(7) Å) relative to free MeCN (1.14 Å), indicating that the nitrile is by no means activated by its interaction with the Fe3+ ion.

Although the curtailed affinity of 3 and 15 for additional ligands could reflect the anionic charge, it could also reflect the presence of an electron in the intermediate-spin apical site orbital (vide supra; Figure S-18). Reactivity has previously been shown by our group to correlate with spin-state.18,38,18,21,38,39 For example, low—spin (S=1/2) five—coordinate [FeIII((Et,Pr)—N3S2Me2)]+ (Et,Pr; Scheme 1) binds a wide variety of ligands including nitriles (RCN, R= Me, Bz, Et, tBu), py, tBuNC, MeOH, and MeC(O)NH2, as well as N3- and NO.18,38 Intermediate-spin (S= 3/2), five-coordinate [FeIII((Pr,Pr)—NMeN2amideS2Me2)]1-, on the other hand, does not appear to bind any of these ligands, even at low temperatures.18,21,38,39 Five-coordinate [FeIII((Pr,Pr)—N3S2Me2)]+ (Pr,Pr; Scheme 1) does not bind N3- at ambient temperatures where an S= 3/2 excited state is 23% populated, but does at low—temperatures (−80 °C) where an S= ½ state is predominantly populated.18 The equilibrium for binding azide favors the azide—bound form of Et,Pr ([FeIII((Et,Pr)N3S2Me2)(N3)]) ten times more than that of Pr,Pr ([FeIII((Pr,Pr)N3S2Me2)(N3)]),38 meaning that an additional 2.3 kcal mol-1 energy is released when azide binds to low-spin (S= 1/2) Et,Pr versus partially (23%) intermediate-spin S= 3/2 Pr,Pr.

Given the potential similarity between [FeIII(tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15) and the uncharacterized unmodified form of NHase, the curtailed reactivity of the former suggests that post—translational oxygenation of the equatorial cysteinate sulfurs plays an important role in promoting substrate binding. This is supported by theoretical (DFT) calculations,1 which predict that the hypothetical unmodified form of NHase has a weak affinity for water (Fe-OH2 = 3.4 Å) unless the equatorial thiolate ligands are oxidized (Fe-OH2 = 2.1 Å). Whereas the catalytically active, post-translationaly modified form of NHase readily binds N3-, CN-, and NO, and hydrolyzes RCN, our unmodified NHase analogue 15 does not bind substrates (RCN) or inhibitors (N3-, CN-, or NO), even when present in excess and at low-temperatures. H—bonding, may also play an important role in NHase activity, as suggested by the inactivity of mutants lacking highly conserved 56Arg and 141Arg.85,86 In order to address the possible roles of thiolate oxidation and/or H-bonding on reactivity we attempted to both oxidize the equatorial sulfurs of 15, and crystallize 15 in the presence of H-bond donors such as H2O.

Unmodified NHase analogue 15 is soluble and stable in H2O. Crystallization from “wet” DMF affords a structure containing two dianionic iron complexes (NEt4)2[FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]•3H2O (15a) and three H2O’s each H—bonded to a different carboxamide oxygen (O(1)•••H(52)(H2O)= 2.010 Å; O(1)-H(52)-O(5)= 163.3°; O(2)•••H(72)(H2O)= 2.049 Å; O(2)-H(72)-O(7)= 176.1°; O(3)•••H(61)(H2O)= 1.998 Å; O(3)-H(61)-O(6)= 169.0°; Figure S—23). Comparison of the two structures (15 versus 15•3H2O) shows very little change in carboxamide C—N (mean distance= 1.339(2) Å in 15•3H2O versus 1.337(3) Å in 15) and C=O (mean distance= 1.26(1) Å in 15•3H2O versus 1.255(3) Å in 15) bond distances (Table 2). The H—bonded complex 15•3H2O (Figure S-23) remains five-coordinate, and intermediate-spin S= 3/2. This is true even when excess guanidinium•HCl is added, as a potential H-bond donor and mimic for the conserved arginine residues,86 suggesting that sulfur oxygenation plays a more important role than H-bonding in determining magnetic and reactivity properties.

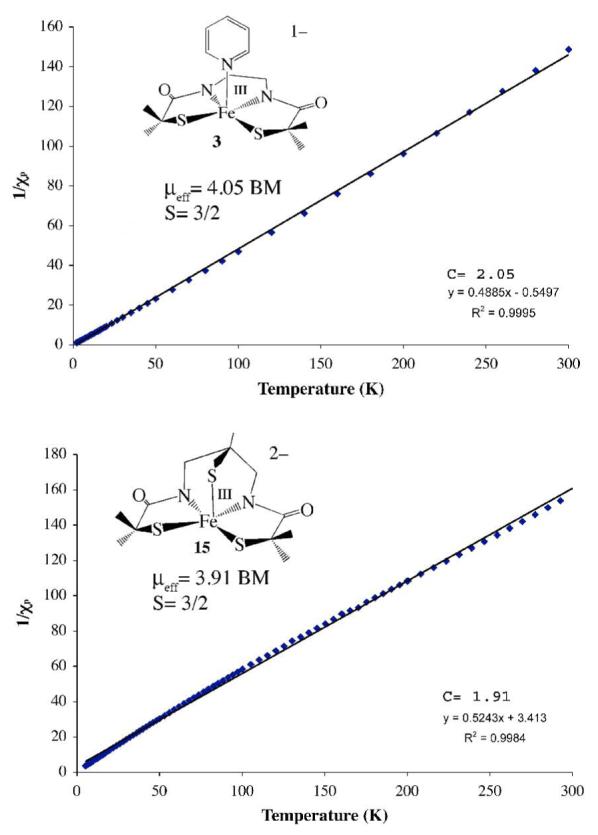

Reactivity of Unmodified NHase Analogue [FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15) with Dioxygen

Addition of dry O2 to [FeIII((tame—N2S)S2Me2)]2- (15) in MeCN results in the addition of two oxygen atoms to the parent molecule as determined by ESI-MS. X-ray quality crystals of this oxygenated product were obtained upon low temperature (−35 °C) layering of Et2O onto an MeCN solution. As shown in the ORTEP of Figure 8 the apical thiolate sulfur is selectively oxidized by O2, to afford O-bound sulfinate—ligated [FeIII((tame—N2SO2)S2Me2)]2- (20). Preferential oxygenation of the apical sulfur occurs initially because the apical Fe—S(3) bond is significantly longer, making it the most basic sulfur, and thus more susceptible to oxidation, than the basal plane sulfurs S(1) and S(2). Rearrangement of this kinetic product to a potentially different thermodynamically preferred product would be expected to be slow, since it would involve cleavage of fairly robust S=O bonds. Oxygenation of 15′s apical sulfur not only leaves the S= 3/2 spin—state (∝eff = 3.75 ∝B (Figure S—24); g∞ = 3.74, g→| = 2.02 (Figure S—25)) and bond lengths (Table S—2) unperturbed, but reactivity is unaffected as well. Like 15, sulfinate-ligated 20 does not bind anionic (N3-, CN-), neutral (Py, CO, NO) and/or σ-donor ligands (MeCN), even when added in excess (>100 eq) and at low temperatures (−78 °C), as determined by electronic absorption spectroscopy. Given the similarity between 20 and the NHase active site, this implies that regioselective post-translational oxygenation of the basal plane sulfurs is critical to NHase function. In the enzyme, apical thiolate oxidation is prevented by its placement in a solvent inaccessible site.16 The basal plane sulfurs, on the other hand, point towards a solvent accessible channel. Oxygenation of the basal sulfurs would weaken the basal plane ligand-field by “tying up” the π-symmetry sulfur orbitals, increase the metal ion Lewis acidity, and thereby increase the apical Fe—S interaction17 causing a spin-state change from S= 3/2 to S= ½ (Figure S-18). The low spin S= ½ state would possess a more Lewis acidic dz2 orbital that would more readily bind apical ligands.87.

Figure 8.

ORTEP of the anion of (NEt4)2[FeIII((tame—N2SO2)S2)]•MeCN (20) showing 50% ellipsoids and atom labeling scheme.

Summary and Conclusions

The strong N2S2 basal plane ligand-field and anionic charge of equatorial carboxamides in the thiolate-ligated complexes described herein, results in a significantly weakened apical ligand interaction, even with tethered built-in ligands. Introduction of an apical thiolate in place of an amine does pull the Fe3+ ion out of the basal N2S2 plane, however, indicating that it has a higher affinity for thiolates. Spin-state may be responsible for reduced apical ligand affinity,18,87,88 since the intermediate S= 3/2 spin—system, for all of the ligand-field combinations examined herein, would have an electron in the orbital (dz2) pointing towards the vacant site. This is in contrast to the post-translationaly modified NHase active site, which is low-spin, with an empty apical site orbital, and displays a higher affinity for apical ligands. Since the preferred ground state of six-coordinate iron thiolate complexes is S = ½,13,14,23,59 “substrate” binding to an S=3/2 spin-system would require a spin-state change involving the pairing of electrons, and this could create an additional barrier to ligand binding. The mechanism by which NHase operates has yet to be elucidated. It has been proposed that the iron site serves as either a hydroxide source, or as a Lewis—acidic site to which nitriles coordinate.4,8,16,26,29-36 Both mechanisms would require ligand binding to the vacant apical site. The results described herein suggest that regioselective post-translational oxygenation of the basal plane NHase cysteinates is required in order to weaken the equatorial ligand field, and increase the Lewis acidity of the dz2 orbital pointing towards the vacant apical site. Density functional calculations support this.1

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

The post—translationally modified NHase active site.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH (#GM 45881). P. L. -M. gratefully acknowledges support by an NIH pre-doctoral minority fellowship (# F31 GM73583-01).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Contains experimental data for the tame—(NH)2(SH)3 (14) ligand synthesis, including ESI mass spec, IR, and 1H NMR data. Experimental, and crystallographic data for complexes 1 — 3, 15, 15a•3H2O, 16, and 18-20. An ORTEP diagram of 15a•3H2O. Electronic absorption spectra of 1—3 and 15. Magnetic data for 1 and 20. X-band EPR spectra of 1—3, and 20. A cyclic voltammogram of 3. And, vibrational data for CO—bound 16 and NO—bound 18. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Dey A, Chow M, Taniguchi K, Lugo-Mas P, Davin SD, Maeda M, Kovacs JA, Odaka M, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:533–541. doi: 10.1021/ja0549695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Mitra S, Holz RC. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7397–7404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Noguchi T, Nojiri M, Takei K, Odaka M, Kamiya N. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11642–11650. doi: 10.1021/bi035260i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Nature Biotechnology. 1998;16:733–736. doi: 10.1038/nbt0898-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Sugiura Y, Kuwahara J, Nagasawa T, Yamada H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:5848–5850. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Stolz A, Trott S, Binder M, Bauer R, Hirrlinger B, Layh N, Knackmuss H-J. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 1998;5:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Nagashima S, Nakasako M, Naoshi D, Tsujimura M, Takio K, Odaka M, Yohda M, Kamiya N, Endo I. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Huang W, Jia J, Cummings J, Nelson M, Schneider G, Lindqvist Y. Structure. 1997;5:691–699. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que LJ. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Emerson JP, Farquhar ER, Que L. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:8553–8556. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Pau MYM, Lipscomb JD, Solomon E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:18355–18362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Joseph CA, Maroney MJ. Chem. Comm. 2007:3338–3349. doi: 10.1039/b702158e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kovacs JA. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:825–848. doi: 10.1021/cr020619e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kovacs JA, Brines LM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:501–509. doi: 10.1021/ar600059h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Song L, Wang M, Shi J, Xue Z, Wang M-X, Qian S. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2007;362:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Nagashima SN,M, Naoshi D, Tsujimura M, Takio K, Odaka M, Yohda M, Kamiya N, Endo I. Nature Structural Biology. 1998;5:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lugo-Mas P, Dey A, Xu L, Davin SD, Benedict J, Kaminsky W, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11211–11221. doi: 10.1021/ja062706k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Shearer J, Jackson HL, Schweitzer D, Rittenberg DK, Leavy TM, Kaminsky W, Scarrow RC, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11417–11428. doi: 10.1021/ja012555f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Shearer J, Kung IY, Lovell S, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:463–468. doi: 10.1021/ja002642s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kennepohl P, Neese F, Schweitzer D, Jackson HL, Kovacs JA, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:1826–1836. doi: 10.1021/ic0487068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ellison JJ, Nienstedt A, Shoner SC, Barnhart D, Cowen JA, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5691–5700. [Google Scholar]

- (22).da Silva J. J. R. Frausto, Williams RJP. The Inorganic Chemistry of Life. 2nd Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2001. The Biological Chemistry of the Elements. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Shoner S, Barnhart D, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 1995;34:4517–4518. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ellison JJN,A, Shoner SC, Barnhart D, Cowen JA, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5691–5700. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Schweitzer DE,JJ, Shoner SC, Lovell S, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10996–10997. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Scarrow RC, Strickler B, Ellison JJ, Shoner SC, Kovacs JA, Cummings JG, Nelson MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9237–9245. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Mascharak PK, Harrop TC. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:253–260. doi: 10.1021/ar0301532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Mascharak PK. Coord. Chem. 2002;225:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hopmann KH, Himo F. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2008:1406–1412. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Odaka M, Fujii K, Hoshino M, Noguchi T, Tsujimura M, Nagashima S, Yohada N, Nagamune T, Inoue I, Endo I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:3785–3791. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Scarrow RC, Brennan BA, Nelson MJ. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10078–10088. doi: 10.1021/bi960164l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Jin H, Turner IM, Jr., Nelson MJ, Gurbiel RJ, Doan PE, Hoffman BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:5290–5291. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Nelson MJ, Jin H, Turner IM, Jr., Grove G, Scarrow RC, Brennan BA, Que L., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7072–7073. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Brennan BA, Cummings JG, Chase DB, Turner IM, Jr., Nelson MJ. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10068–10077. doi: 10.1021/bi960163t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bonnet D, Artaud I, Moali C, Petre D, Mansuy D. FEBS Lett.s. 1997;409:216–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Greene SN, Richards NGJ. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:17–36. doi: 10.1021/ic050965p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Miyanaga A, Fushinobu S, Ito K, Shoun H, Wakagi T. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:429–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Schweitzer D, Shearer J, Rittenberg DK, Shoner SC, Ellison JJ, Loloee R, Lovell SC, Barnhart DK,JA. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:3128–3136. doi: 10.1021/ic0109187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lugo-Mas PT,W, Schweitzer D, Theisen RM, Xu L, Shearer J, DiPasquale A, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. 2008. submitted (#ja-2008-03414b) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (40).Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:601–608. doi: 10.1021/ar700008c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Yandulov DV, Schrock RR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:6252–6253. doi: 10.1021/ja020186x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Smith JM, Sadique AR, Cundari TR, Rodgers KR, Lukat-Rodgers G, Lachicotte RJ, Flaschenriem CJ, Vela J, Holland PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:756–769. doi: 10.1021/ja052707x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).O’Keefe BJ, Breyfogle LE, Hillmyer MA, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:4384–4393. doi: 10.1021/ja012689t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Brown SD, Betley TA, Peters JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:322–323. doi: 10.1021/ja028448i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).MacBeth CE, Hammes BS, Young VG, Borovik AS. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:4733–4741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Hagen KS, Holm RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:5496–5497. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Millar M, Lee JF, Koch SA, Fikar R. Inorg. Chem. 1982;21:4105–4106. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Gebhard MS, Deaton JC, Koch SA, Millar M, Solomon EI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2217–2231. doi: 10.1021/ja00226a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Lippard SJ, Berg JM. Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry. University Science; Mill Valley: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Shoner SC, Nienstedt A, Ellison JJ, Kung I, Barnhart D, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:5721–5725. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Krishnamurthy D, Sarjeant AN, Goldberg DP, Caneschi, Totti F, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:7328–7341. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Brines LM, Shearer J, Fender JK, Schweitzer D, Shoner SC, Barnhart D, Kaminsky W, Lovell S, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:9267–9277. doi: 10.1021/ic701433p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Brines LMV-A,G, Kitagawa T, Swartz RD, Lugo-Mas P, Kaminsky W, Benedict JB, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2008;361:1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2007.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Liu S, Wong E, Karunaratne V, Rettig SJ, Orvig C. Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:1756–1765. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Song B, Reuber J, Ochs C, Hahn FE, Lugger T, Orvig C. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:1527–1535. doi: 10.1021/ic0009831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Kruger HJ, Peng G, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 1991;30:734–742. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Addison AW, Rao TN, Reedijk J. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984:1349. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Pauling L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond. 3rd Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Jackson HL, Shoner SC, Rittenberg D, Cowen JA, Lovell S, Barnhart D, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:1646–1653. doi: 10.1021/ic001271d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Shearer J, Fitch SB, Kaminsky W, Benedict J, Scarrow RC, Kovacs JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., USA. 2003;100:3671–3676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0637029100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Shearer J, Nehring J, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:5483–5484. doi: 10.1021/ic010221l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Schweitzer D, Ellison JJ, Shoner SC, Lovell S, Kovacs JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10996–10997. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Roelfes G, Lubben M, Chen K, Ho RYN, Meetsma A, Genseberger S, Hermant RM, Hage R, Mandal SK, Young VG, Zang Y, Kooijman H, Spek AL, Que L, Jr, Feringa BL. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1929–1936. doi: 10.1021/ic980983p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Zang Y, Kim J, Dong Y, Wilkinson EC, Appelman EH, Que L., Jr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997:4197–4205. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Roelfes G, Lubben M, Chen K, Ho RYN, Mettsma A, Genseberger S, Hermant RM, Hage R, Mandal SK, Young VG, Jr., Zang Y, Kooijman H, Spek AL, Que L, Jr., Feringa BL. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1929–1936. doi: 10.1021/ic980983p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Marlin DS, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:3258–3260. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Noveron JC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:1138–1139. doi: 10.1021/ic971388a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Noveron JC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3247–3259. doi: 10.1021/ja001253v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Theisen RM, Shearer J, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:7682–7690. doi: 10.1021/ic0491884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Tyler LA, Noveron JC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:616–617. doi: 10.1021/ic990794m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Collins TJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1994;27:279. [Google Scholar]

- (72).Keutel H, Käpplinger I, Jäger EG, Grodzicki M, Schunemann V, Trautwein AX. Inorganic chemistry. 1999;38:2320–2327. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Fettouhi M, Morsy M, Waheed A, Golhen S, Ouahab L, et al. Inorg. Chem. 1999 doi: 10.1021/ic990299q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Kostka KL, Fox BG, Hendrich MP, Collins TJ, Rickard CEF, Wright LJ, Munck E. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- (75).Simonato JP, Pécaut J, Le Pape L, Oddou JL, Jeandey C, Shang M, Scheidt WR, Wojaczyński J, Wołowiec S, Latos-Grazyński L, Marchon JC. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:3978–3987. doi: 10.1021/ic000150a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Keutel H, Käpplinger I, Jäger EG, Grodzicki M, Schunemann V, Trautwein AX. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:2320–2327. [Google Scholar]

- (77).Fettouhi M, Morsy M, Waheed A, Golhen S, Ouahab L. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:4910–4912. doi: 10.1021/ic990299q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Kostka KL, Fox BG, Hendrich MP, Collins TJ, Rickard CEF, Wright LJ, Munck E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:6746–6757. [Google Scholar]

- (79).Collins TJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 1994;27:279–285. [Google Scholar]

- (80).Harrop TC, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:9527–9533. doi: 10.1021/ic051183z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Kruger HJ, Holm RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2955–2963. [Google Scholar]

- (82).Kruger HJ, Peng G, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 1991;30:734–742. [Google Scholar]

- (83).Meyerstein D, Goldstein S. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:547–550. [Google Scholar]

- (84).Nguyen DH, Hsu HF, Munck E, Millar M, Koch SA. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8963–8964. [Google Scholar]

- (85).Piersma SR, Nojiri M, Tsujimura M, Noguchi T, Odaka M, Yohda M, Inoue Y, Endo I. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000;80:283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Endo I, Nojiri M, Tsujimura M, Nakasako M, Nagashima S, Yohda M, Odaka M. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001;83:247–253. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Strickland N, Harvey JN. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:841–852. doi: 10.1021/jp064091j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Carreon-Macedo JL, Harvey JN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5789–5797. doi: 10.1021/ja049346q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.