Abstract

Hepsin is a type-II transmembrane serine protease overexpressed in the majority of human prostate cancers. We recently demonstrated that hepsin promotes prostate cancer progression and metastasis and thus represents a potential therapeutic target. Here we report the identification of novel small-molecule inhibitors of hepsin catalytic activity. We utilized purified human hepsin for high-throughput screening of established drug and chemical diversity libraries and identified sixteen inhibitory compounds with IC50 values against hepsin ranging from 0.23–2.31μM and relative selectivity of up to 86-fold or greater. Two compounds are orally administered drugs established for human use. Four compounds attenuated hepsin-dependent pericellular serine protease activity in a dose dependent manner with limited or no cytotoxicity to a range of cell types. These compounds may be used as leads to develop even more potent and specific inhibitors of hepsin to prevent prostate cancer progression and metastasis.

Keywords: hepsin, prostate, metastasis, inhibitor, cancer

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in United States males, with an estimated 186,320 new cases in 2008, accounting for 25% of cancer incidence and 10% of cancer deaths (1). While significant progress has been made in recent years in the understanding molecular mechanisms responsible for prostate cancer initiation and progression, therapeutic approaches for the treatment of prostate cancer remain limited. While localized prostate tumors are usually curable, diagnosis of prostate cancer remains a difficult, inexact process and treatment can result in side effects that significantly impact quality of life (2, 3). Metastatic prostate cancer is highly resistant to therapeutic intervention and almost uniformly fatal. Therefore, the development of effective novel targeted therapies to inhibit prostate cancer progression and metastasis will have a significant impact on prostate cancer mortality.

Multiple genetic and epigenetic changes take place during human prostate cancer initiation and progression (4, 5). Hepsin (HPN) is one of the most upregulated genes in human prostate cancer and encodes a type-II serine protease overexpressed in up to 90% of prostate tumors with levels often increased >10 fold (6–8). Hepsin is upregulated early in prostate cancer initiation and maintained at high levels throughout progression and metastasis. In addition, hepsin is also overexpressed in ovarian and renal carcinomas (9, 10).

Significant evidence indicates that hepsin overexpression plays an important role in the promotion of prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Hepsin upregulation in a transgenic mouse model of localized prostate cancer promoted progression, causing the transition of nonmetastatic cancer into an aggressive carcinoma with metastasis to bone, liver and lung (11). The cellular context and level of hepsin expression appear to be important to the phenotype, as high levels of hepsin overexpression in a prostate cancer cell line reduces cell proliferation and invasion (12). While the molecular mechanisms responsible for hepsin function in prostate cancer in vivo are unknown, in vitro evidence indicates that hepsin can activate pro-urokinase plasminogen activator (pro-uPA) and pro-hepatocyte growth factor (pro-HGF) (13, 14). Activation of the uPA cell-surface serine protease system and HGF-Met scattering pathway may be responsible for hepsin promoting metastasis and is consistent with the observed basement membrane disruption in mouse prostates overexpressing hepsin (11).

We sought to identify small molecules that specifically inhibit hepsin catalytic activity that may be used as lead compounds to develop targeted drugs to attenuate prostate cancer progression. Protease-targeted drugs have proven to be clinically useful for treatment of HIV and hypertension and show potential in the treatment of cancer, obesity, cardiovascular, inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases (15). WX-UK1 is a potent small-molecule inhibitor of uPA developed by Wilex and has shown antitumor and antimetastasis activity in a rat breast cancer model (16). WX-UK1 has completed phase Ib trials in patients with solid tumors and is currently in combination phase I trials with capecitabine in patients with breast cancer and other solid tumors.

We report here the identification of sixteen compounds that potently and selectively inhibit hepsin proteolytic activity. Four members are able to attenuate hepsin-dependent pericellular proteolytic activity with low or no general cellular toxicity. Two of the sixteen compounds are established human-use drugs used for alternate indications with known oral dosing strategies. We propose that these newly identified small molecules may be used as lead compounds for generation of potent and specific drugs for the treatment of human prostate cancer.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

The DIVERSet and NINDS II compound libraries and reordered hit compounds from those libraries were purchased from Chembridge Corporation and MicroSource Discovery Systems, Inc., respectively. The chromogenic peptide pyroGlu-Pro-Arg-pNA (S-2366) was purchased through Diapharma Group, Inc. Rabbit anti-human hepsin polyclonal antibody was purchased from Cayman Chemical (#100022) and goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse hepsin antiserum was produced against a synthetic peptide corresponding to the last 18 amino acids of mouse hepsin. Molecular biology grade DMSO was purchased from Fluka. Trypsin was purchased from ICN (#103140) and thrombin was purchased from Sigma (T-3399).

Recombinant Hepsin Expression and Purification

Recombinant expression and chromatographic purification of human hepsin was performed as described previously (17).

Compound Library Screening

The DIVERSet 10,000 compound and NINDS II 1040 compound libraries were diluted from 20 and 10μM stock plates in DMSO (respectively) to 20μM 10X solutions in 10% DMSO. Purified hepsin was incubated with 2μM compounds in 30mM Tris-HCl, 30mM imidazole, 200mM NaCl and 1% DMSO for 30 minutes at room temperature. Chromogenic peptide was added and the reactions allowed to proceed for 3 hours. Endpoint absorbance was measured using a VersaMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices), corrected for background and residual activity observed relative to buffer/solvent controls on each plate.

Hepsin, Trypsin and Thrombin Activity Assays

Titration of the chromogenic substrate pyroGlu-Pro-Arg-pNA was performed for each enzyme and the resulting substrate-velocity data fit with nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 4 to calculate Vmax and Km. Enzyme assay concentration and observed Km: 0.4nM hepsin, Km=170μM, 0.4nM trypsin, Km=78.6μM, thrombin 188mU/mL, Km=106.2μM. Inhibitor activity was determined by incubating the individual enzymes with increasing concentrations of compounds in the library screen buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature followed by addition of the substrate at the observed Km. The reactions were then followed using a kinetic microplate reader and the linear rates of increase in absorbance at 405nm expressed as residual percent activity (100% × vi/vo). At least three independent experiments were performed for each enzyme. IC50 was calculated by fitting the data to a four-parameter non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism 4. The equilibration time dependence of inhibitor potency was determined by incubating hepsin with the respective inhibitor at its IC50 value or buffer/solvent alone under the above conditions in triplicate. Samples were withdrawn at 30, 60, 120 and 180 minutes and activity analyzed by the addition of substrate as above. Data are shown as percent inhibition relative to the respective buffer/solvent controls incubated for the same amount of time. The reversibility of inhibition was determined using a dilution technique. Hepsin was incubated with the inhibitors at their respective IC50 values or buffer control as above for 1 hour at room temperature in triplicate. Samples were then diluted with buffer to the additional percentage indicated and activity measured as above. Data are shown as percent inhibition relative to the respectively diluted buffer controls.

Cell Culture

LNCaP, HepG2 and HEK 293FT cells were purchased from ATCC. The spontaneously transformed mouse prostate epithelial cell line MP-1 was established by passaging C57/B6 primary mouse prostate epithelial cells. Cell culture components and suppliers were as follows: DMEM, F12 and RPMI base medias (Invitrogen), hydrocortisone (Calbiochem), insulin, T3 and cholera toxin (Sigma). Cells were incubated in a humidified (37°C, 5% CO2) incubator and passaged at 80% confluence with trypsin/EDTA. Mouse prostate epithelial cells MP-1 were maintained in E-media containing: 3:1 DMEM/F12, 37mM sodium bicarbonate, 0.42μg/mL hydrocortisone, 0.89ng/mL cholera toxin, 5.3μg/mL insulin, 5.3μg/mL transferrin, 2.1×10−11M T3, pen/strep and L-glutamine with 15% FCS. LNCaP cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS and pen/strep. HepG2 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and pen/strep. 293FT cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, L-glutamine, non-essential amino-acids and pen/strep.

Cell Cytotoxicity Assay

The general cytotoxicity of the compounds was determined using the CellTiter-Glo Assay from Promega. Mouse prostate epithelial, LNCaP and HepG2 cells were seeded in 96-well black culture plates at 2×104 cells per well and allowed to attach. Media was aspirated and compounds were administered at 20μM in the appropriate media and media with compounds was changed at 24 and 48 hours. CellTiter-Glo reagent was added to the cells and ATP-coupled luciferase activity recorded on a microplate luminometer.

Pericellular Serine Proteolytic Activity Assay

Plasmids encoding full-length mouse wild-type, active-site S352A mutant hepsin (Genbank: NM008281) cDNAs or the empty pLNCX2 vector were transfected into HEK 293FT cells using a calcium phosphate protocol. After 3.5hrs, transfect media was replaced with fresh media containing 20 μ or 50μM of test compounds or solvent control (0.5% DMSO in media) and cells incubated to 24 hours post-transfection. Attached cell monolayers were then washed twice with PBS and once with assay buffer (5% CO2 equilibrated phenol-red free DMEM with 1% BSA) to remove residual serum proteases/inhibitors. Cells were then incubated in assay buffer containing 20 or 50μM compounds for 30 minutes at 37°C. Peptide substrate was then added to a final concentration of 369 μM (observed Km in this system) and the reactions allowed to proceed at 37°C. Samples were withdrawn at 20, 40 and 60 minutes, quenched into an equal volume of 7% acetic acid and absorbance at 405nm measured with a microplate reader. Percent inhibition was calculated as residual activity relative to solvent control. Matched samples were used in parallel to determine toxicity of the test compounds to HEK 293FT cells in this system using the CellTiter-Glo assay.

Immunoblotting

Total protein lysates from transfected, compound treated HEK 293FT cells were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membrane. The membrane was blocked overnight in TBST buffer containing: 5% non-fat milk, 2% normal goat serum in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20. The membrane was then incubated in 3% BSA in TBST with polyclonal anti-mouse hepsin antibody (1:1000) for two hours at room temperature, washed 3×5 minutes with TBST and incubated for one hour in 0.1% BSA in TBST containing goat-anti-rabbit-HRP secondary antibody (1:2000), washed 3×5 minutes in TBST and developed with ECL (Pierce). Protein loading was confirmed by stripping the membrane and reprobing with anti-β-actin antibodies. Expression levels were quantified by densitometry using ImageQuantTL.

Results

Expression and Purification of the Recombinant Extracellular Region of Hepsin

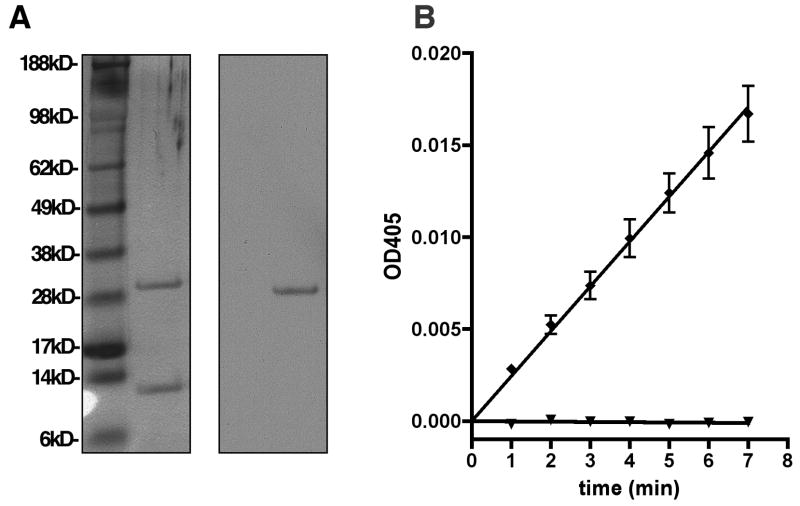

The extracellular region of human hepsin consists of residues Ser46 to Leu417 (Genbank: BC025716) and contains the catalytic and scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) domain. The yeast P. pastoris was stably transfected with the hepsin expression construct and the secreted 41kD hepsin zymogen was purified from the media using several steps of affinity and ion exchange chromatography. During purification to homogeneity, the enzyme spontaneously activated as previously reported (17). Protein identity was confirmed by silver stain of SDS-PAGE separated samples and immunoblotting with anti-hepsin catalytic domain polyclonal antibodies (Figure 1A). The purified hepsin was enzymatically active (Figure 1B), cleaving the chromogenic serine protease substrate pyroGlu-Pro-Arg-pNA. This proteolytic activity was completely inhibited by the broad-spectrum serine protease inhibitor PEFAbloc.

Figure 1.

Characterization of recombinant active hepsin. A, Chromatographically purified recombinant human hepsin was produced in P. pastoris and analyzed by silver staining of SDS-PAGE gel and immunoblotting with anti-hepsin catalytic domain antibodies. B, Purified hepsin is proteolytically active and inhibited by a broad-spectrum serine protease inhibitor. 0.4nM purified hepsin was incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes in buffer alone (diamonds) or in the presence of 4mM PEFAbloc (triangles). The chromogenic serine protease substrate pyroGlu-Pro-Arg-pNA was then added and enzyme activity observed as a linear increase in absorbance at 405nm over time.

High-Throughput Screening and Characterization of Hit Compounds

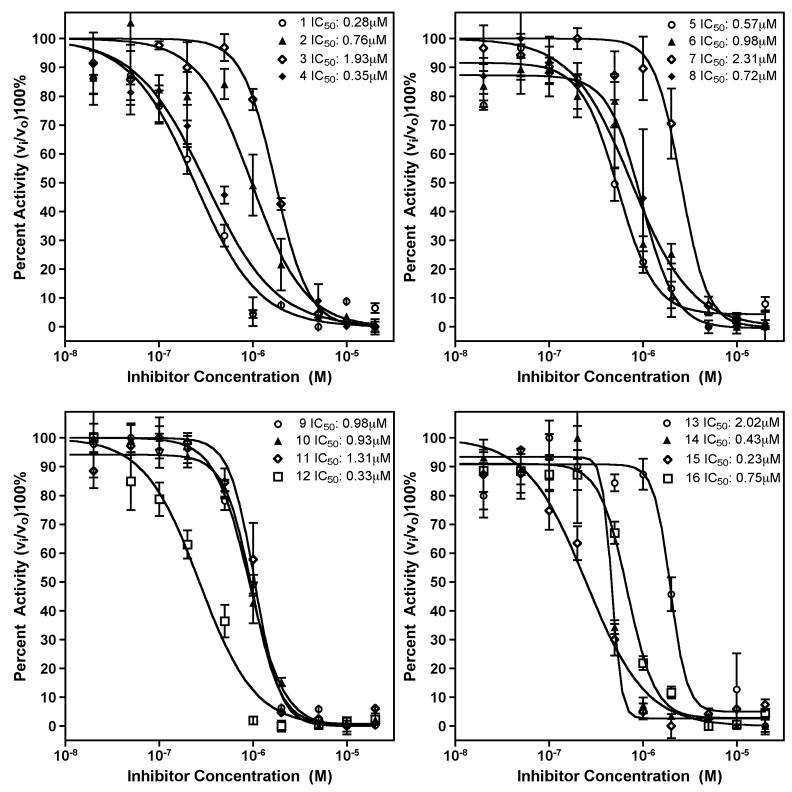

To identify novel inhibitors of hepsin, we screened the Chembridge DIVERSet 10,000 compound high-diversity library using an assay based on the cleavage of the chromogenic peptide. In addition, the NINDS II library of 1040 compounds was screened to identify hepsin inhibitors among established drugs and known bioactive molecules. Screens were performed in a 96-well format at a final compound concentration of 2μM. To minimize false positives, positions 1 and 12 of each row contained DMSO/buffer controls. As a measure of reproducibility, the Z’ score for this assay was 0.78 (18). Compounds that showed ≥90% inhibition were individually reproduced. Reproduced hits were reordered from the supplier and their inhibitory activity was confirmed (Figure 2). IC50 values for these compounds were determined by titration of the compounds against kinetic hepsin activity (Figure 3). Relative specificity was determined by titration against the serine proteases trypsin and thrombin (Table 1).

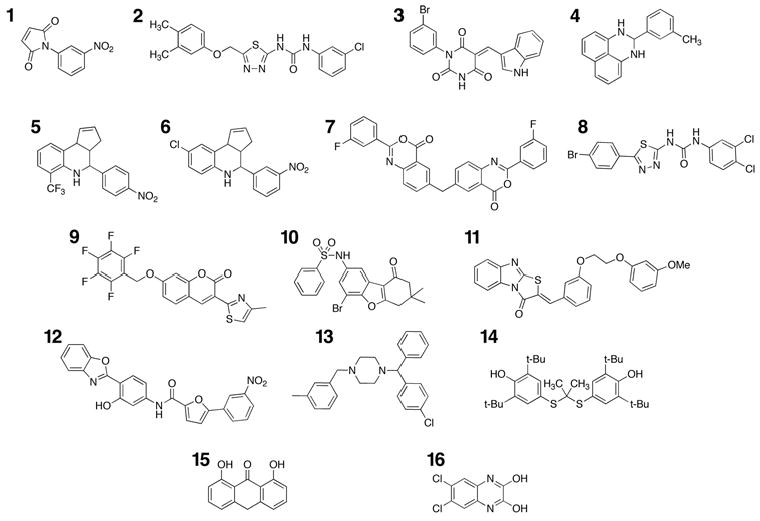

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of identified hepsin inhibitors. Compounds 1–12 were identified from the ChemBridge DIVERSet library. Compounds 13–16 (meclizine, probucol, anthralin and 2,3-dihydroxy-6,7-dichloroquinoxaline) were identified from the NINDS II library of known drugs and bioactives.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of hepsin activity by identified compounds. A, Compounds 1–4. B, Compounds 5–8. C, Compounds 9–12. D, Compounds 13–16. Purified recombinant hepsin was preincubated with indicated compounds for 30 minutes at room temperature. The residual percent activity of the enzyme toward the chromogenic substrate was then determined with a kinetic microplate reader at 405nm. The data are the mean of three independent experiments. IC50 was calculated by four-parameter non-linear regression curve fitting.

Table 1.

Protease inhibitory activities of the compounds identified from library screening.

| Compound | Library | ID | IC50 hepsin (μM) | IC50 trypsin (μM) | IC50 thrombin (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chembridge Diverset | 5133201 | 0.28±0.07 | 3.88±0.85 | * |

| 2 | Chembridge Diverset | 6066621 | 0.76±0.26 | >20 | >20 |

| 3 | Chembridge Diverset | 6232890 | 1.93±0.39 | 7.63±1.51 | >20 |

| 4 | Chembridge Diverset | 6071655 | 0.35±0.12 | 19.6±2.7 | >20 |

| 5 | Chembridge Diverset | 5655336 | 0.57±0.19 | 31.2±2.0 | >20 |

| 6 | Chembridge Diverset | 5658856 | 0.98±0.20 | 10.2±1.5 | >20 |

| 7 | Chembridge Diverset | 5770901 | 2.31±0.53 | 13.1±3.0 | >20 |

| 8 | Chembridge Diverset | 6066971 | 0.72±0.20 | 1.71±0.21 | >20 |

| 9 | Chembridge Diverset | 6238388 | 0.98±0.12 | 20.9±7.5 | >20 |

| 10 | Chembridge Diverset | 6132801 | 0.93±0.13 | 7.72±1.10 | >20 |

| 11 | Chembridge Diverset | 6176059 | 1.31±0.44 | 2.00±0.33 | >20 |

| 12 | Chembridge Diverset | 6011640 | 0.33±0.07 | 3.50±0.67 | >20 |

| 13 | NINDS II | meclizine | 2.02±0.37 | >20 | >20 |

| 14 | NINDS II | probucol | 0.43±0.05 | 33.5±11.5 | >20 |

| 15 | NINDS II | anthralin | 0.23±0.05 | 1.26±0.30 | >20 |

| 16 | NINDS II | NMDA receptor antagonist | 0.75±0.09 | 2.42±0.29 | >20 |

Compound 1 activated thrombin activity, approximately 3-fold at 1μM.

The determined IC50 values for these compounds against hepsin displayed a range of 0.28–2.31μM. Compounds 1, 3, 7, 9 and 10 are subject to nucleophilic addition and may react with the active site serine γO. 2 and 8 share a chlorophenyl substituted thiadiazolurea core, with compound 2 displaying higher selectivity. Compounds 5 and 6 share a tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinoline core, with 5 displaying both higher potency and selectivity. Compound 3 shares an indole moiety with LY178550 (19), the N-H of which forms a hydrogen bond to the γO of the catalytic serine of thrombin.

We observed four total hits from the NINDS II library of drugs and bioactive molecules (compounds 13–16). Interestingly, 13 and 14 (meclizine and probucol) are established human-use drugs with oral dosing. 15 (anthralin) is a topically administered anti-psoriatic agent. Compound 16 (2,3-dyhydroxy-6,7-dichloroquinoxaline, an NMDA receptor antagonist) shares a tetrasubstituted pyrazine with amiloride, a selective, moderately potent uPA inhibitor (20).

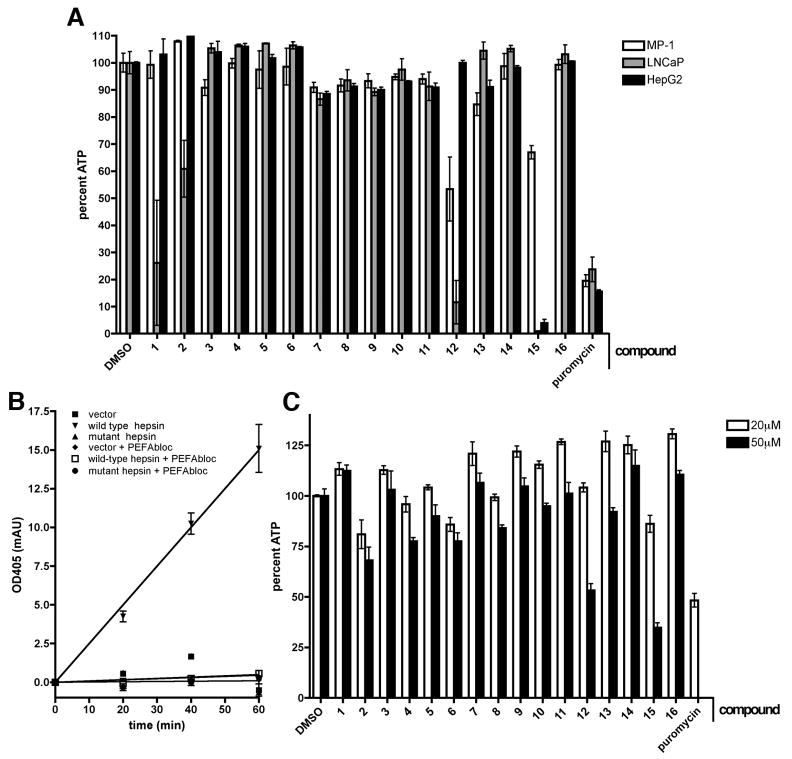

General Cellular Toxicity

To provide an estimate of cellular toxicity and the usefulness of the identified inhibitors in cell-based systems, we performed general cellular toxicity assays. For this purpose, 20μM compounds were incubated with a variety of cell types including the mouse prostate epithelial cell line MP-1, the human hepatoma cell line HepG2 and the human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP (Figure 4A). Compounds and media were replenished daily for three days. At the end of incubation, cell viability was measured using an ATP-luciferase coupled assay. Compounds 1 and 2 displayed substantial toxicity to LNCaP cells without affecting MP-1 or HepG2 cells. Compound 12 was substantially toxic to LNCaP and MP-1 without affecting HepG2. Compound 15 (a known inhibitor of cellular respiration, metabolism and DNA synthesis (21)) was toxic to all cell types, particularly to LNCaP and HepG2 cells. Compounds 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14 and 16 displayed limited or no cytotoxicity to these cells at this concentration.

Figure 4.

Cellular toxicity of identified inhibitors and hepsin-dependent pericellular serine protease assay. A, The mouse prostate epithelial cell line MP-1 (white bars), human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP (grey bars) and human hepatoma cell line HepG2 (black bars) were incubated for 72 hours with 20μM indicated compounds in media with 0.5% DMSO. Media and drugs were replaced every 24 hours. Cell viability was then determined by an ATP-luciferase coupled assay. Puromycin at 5μg/mL and DMSO at 0.5% were used respectively as positive control and negative controls.

B, 293FT cells expressing full-length wild-type, catalytically inactive mouse hepsin mutant or empty vector were incubated for 30 minutes in serum-free media containing vehicle alone or the broad spectrum serine protease inhibitor PEFAbloc. The chromogenic serine protease substrate pyroGlu-Pro-Arg-pNA was then added to the media. The media with cleaved substrate was collected at indicated times, quenched and pericellular proteolytic activity observed as absorbance at 405nm. Note that only the cells expressing wild-type hepsin, but not the cells expressing inactive mutant hepsin, vector alone or wild-type hepsin in the presence of PEFAbloc displayed pericellular proteolytic activity. C, Toxicity of the compounds over the course of the pericellular protease assay was evaluated by 24-hour treatment of cells with 20 μM (white bars) or 50 μM (black bars) compounds relative to vehicle control. Cell viability was then determined by an ATP-luciferase coupled assay. Puromycin at 5μg/mL was used as a positive control.

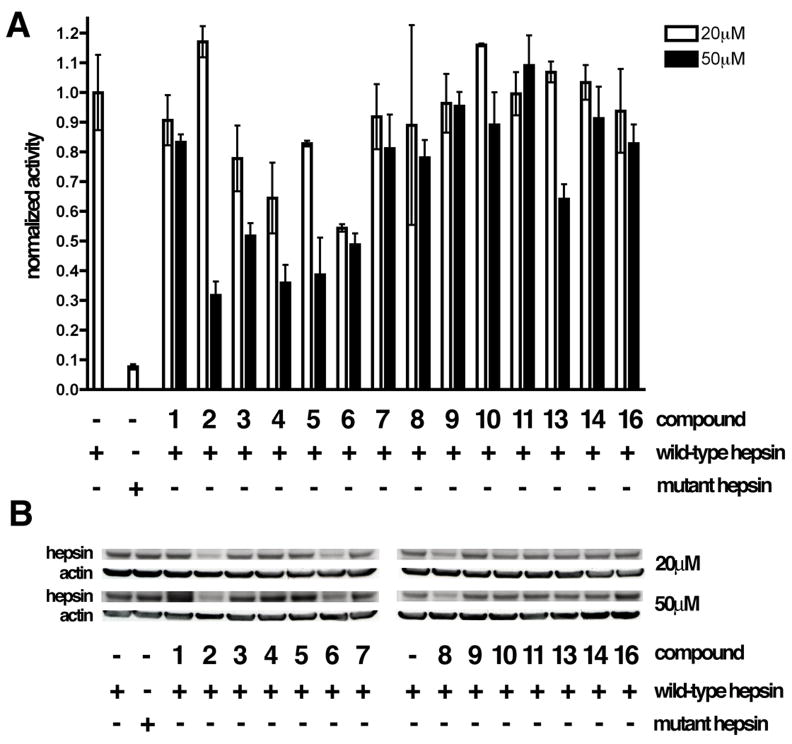

Inhibition of Hepsin-Dependent Pericellular Proteolytic Activity

To determine whether the identified compounds were able to inhibit cell-based hepsin activity, we developed an assay to measure hepsin-dependent pericellular serine-proteolytic activity (Figure 4B) (22–26). For this purpose, we utilized HEK 293FT cells expressing full-length wild-type and catalytically inactive (S352A) mutant mouse hepsin proteins or vector alone. Attached cell monolayers were incubated in assay buffer with peptide substrate and the reactions allowed to proceed at 37°C. Samples were withdrawn at 20, 40 and 60 minutes, quenched into an equal volume of 7% acetic acid and absorbance at 405nm measured with a microplate reader. Activity levels were adjusted by altering hepsin expression levels to within the linear range of detection. A positive linear rate of activity was observed only for wild-type hepsin-expressing cells and was abolished in the presence of the broad spectrum serine protease inhibitor PEFAbloc.

To determine the potential cytotoxicity of the previously identified hepsin inhibitors in this model system, HEK 293FT cells were incubated under identical conditions with 20 and 50μM of the compounds and cytotoxicity was determined using the ATP-luciferase coupled assay as described above (Figure 4C). Compounds 12 and 15 displayed substantial toxicity at 50μM and were not further characterized. The remaining compounds at 20 and 50μM final concentration of were incubated overnight with hepsin-expressing cells and pericellular proteolytic activity was determined in the presence of the compounds, as described above (Figure 5). As treatment with chemical compounds may alter hepsin expression level (and impact pericellular proteolytic activity), hepsin levels in drug-treated cells were determined via immunoblotting. Data are displayed as normalized pericellular proteolytic activity/expression level relative to vehicle treated wild-type hepsin expressing cells. We found that compounds 3, 4, 5 and 13 attenuated pericellular proteolytic activity in a dose dependent manner without substantially affecting hepsin expression levels or displaying overt toxicity. Compounds 4 and 5 offered the most potent inhibition, attenuating activity approximately 60% at 50μM. 3 and 13 reduced activity approximately 50% and 25% (respectively) at 50μM. To further characterize these four compounds, we evaluated the time dependence and reversibility of their biochemical inhibition of hepsin. Inhibition of hepsin by compounds 3, 4, 5 and 13 significantly increased with extended equilibration time (Figure S1) and this inhibition was not reversible by dilution (Figure S2), indicating that these compounds are slow-binding, irreversible inhibitors.

Figure 5.

Attenuation of hepsin-dependent pericellular protease activity by the identified hepsin inhibitors. A, HEK 293FT cells expressing wild-type mouse hepsin, an enzymatically inactive mouse hepsin mutant or vector alone were incubated for 24 hours with 20 μM (white bars) or 50 μM (grey bars) of the biochemically identified hepsin inhibitors and pericellular proteolytic activity was determined in the presence of the inhibitors as described in Figure 5A. As some of the drugs significantly impacted the hepsin expression in HEK 293FT cells, data are displayed as pericellular proteolytic activity/expression level relative to that of vehicle treated wild-type hepsin expressing cells. B, Immunoblot analysis of hepsin expression levels in HEK 293FT cells expressing wild-type and inactive mutant hepsin and treated for 24 hours with indicated drugs. Protein loading was controlled via immunoblotting with anti-β-actin antibodies.

Discussion

We report here the identification of several small molecules that display potent and selective inhibition of the type-II cell-surface serine protease hepsin. Hepsin is overexpressed in human prostate, renal and ovarian cancers and significant evidence implicates hepsin as a metastasis promoting protease in human prostate cancer. Therefore, specific hepsin inhibitors may be useful to attenuate prostate cancer progression and prevent metastasis.

In this study, we identified sixteen hepsin inhibitors utilizing high-throughput screening of small-molecule libraries. To determine the relative selectivity of the newly identified compounds for hepsin, we evaluated their inhibitory activity toward the physiologically relevant serine proteases trypsin and thrombin. Trypsin is a broad-spectrum serine protease with roles in digestion, defense, development and blood coagulation. Thrombin is a chymotrypsin-like serine protease that converts fibrinogen to fibrin and has other roles in blood coagulation. Several of the compounds identified in this study have substantial selectivity for hepsin, with some of the molecules displaying up to 78-fold selectivity toward hepsin versus trypsin and >87-fold selectivity toward hepsin versus thrombin. These IC50 values were determined with relatively short incubation times and it is possible that they were reflective of enzyme-inhibitor association rate differences. Indeed, compounds 3, 4, 5 and 13 displayed a time-dependent increase in hepsin inhibition. In addition, dilution experiments demonstrated that compounds 3, 4, 5 and 13 irreversibly inhibit hepsin. Compound 3 is subject to nucleophilic addition through 1,4-addition and may form a covalent bond with the active site serine γO. The mechanisms that may be responsible for the irreversibility of the inhibition by compounds 4, 5, 13 are less clear. In the future studies, it will be important to rigorously characterize the inhibitory potency and specificity of these compounds under fully equilibrated conditions and to determine their mode of inhibition.

Cell based efficacy is a significant barrier to the development of inhibitors identified with biochemical screens, due to target accessibility, matrix effects and potential non-specific cytotoxicity. To determine the ability of these compounds to inhibit cell-based hepsin activity, we developed a hepsin-dependent pericellular serine protease activity assay. Four of the identified compounds (3, 4, 5 and 13) were able to attenuate pericellular proteolytic activity with limited or no cytotoxicity at effective concentrations. Compounds 4 and 5 were among the most potent inhibitors of hepsin in the purified biochemical assay, however compounds 3 and 13 were among the less potent. This observation, in addition to the increased dosage required to attenuate pericellular activity, may be attributable to the presence of albumin in the cell-based system. Albumin is known to reversibly bind drugs, reduce their concentration free in solution and alter dose-response relationships (27, 28). For example, the non-nucleoside HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitor efavirenz (used as part of highly active antiretroviral therapy, HAART) is more than 99% protein bound in plasma, mainly to albumin (29). Alternatively, it is possible that a portion of the pericellular serine protease activity observed upon hepsin overexpression is due to the hepsin-mediated activation of other serine proteases, which may take place in the Golgi or endoplasmic reticulum (ER), before proteins are delivered to the cell surface. Therefore, lower potency of hepsin inhibitors in the cell-based assay may reflect lower plasma membrane and/or Golgi/ER permeability of these compounds.

Two of the compounds that were identified as non-cytotoxic hepsin inhibitors are orally administered human use drugs. Probucol is an antihyperlipidemic agent developed for use in coronary artery disease and was one of the most potent and specific in vitro inhibitors of hepsin proteolytic activity. Paradoxically, this drug did not reduce pericellular serine protease activity in the cell-based assay. It is possible that probucol showed no activity in the cell-based assay due to the previously mentioned effects of albumin or its high hydrophobicity. This compound has an approximate logP value of 10, is known to be transported almost exclusively by lipoprotein vesicles in serum and delivered from these directly into the cell membrane (30, 31). Water-soluble analogues of probucol (32, 33) have been synthesized and it will be interesting to determine whether these compounds show inhibition of hepsin proteolytic activity and function in a cell-based assay. Meclizine is an anti-nausea drug and available as an over-the-counter remedy for motion sickness. It displayed moderate potency, >10-fold selectivity and was able to attenuate hepsin-mediated pericellular proteolytic activity by 30% at 50μM. Presently, meclizine is one of the most promising lead compounds and provides a template for hepsin inhibitor optimization via medicinal chemistry approaches.

Prostate cancer develops slowly in the majority of cases; however progression to metastasis is highly lethal and can occur rapidly. Treatments to prevent metastasis include radical prostatectomy and radiation therapy, both of which carry significant risk to urinary and sexual function. Metastatic prostate cancer can be treated with androgen ablation therapy, but almost uniformly results in hormone-refractory disease leading to mortality. Effective agents to prevent disease progression would reduce the need for surgical or radiation-based therapies and have a significant impact on prostate cancer related mortality. Hepsin inhibitors derived from the lead compounds identified here may serve this purpose.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Equilibration time dependence of hepsin inhibition. Hepsin was incubated with indicated compounds (A - compound 3, B - compound 4, C - compound 5, D - compound 13) at their respective IC50 values or with buffer/solvent alone. Samples were withdrawn at 30, 60, 120 and 180 minutes and kinetic enzyme activity analyzed by the addition of substrate. Data are shown as percent inhibition relative to the respective buffer/solvent controls, incubated for the same amount of time.

Figure S2. Reversibility of hepsin inhibition. Hepsin was incubated with indicated compounds (A - compound 3, B - compound 4, C - compound 5, D - compound 13) at their respective IC50 values or with buffer/solvent control for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were then diluted with buffer to the additional percentage indicated and kinetic enzyme activity analyzed by the addition of substrate. Data are shown as percent inhibition relative to the respectively diluted buffer controls.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Katherine Pratt (Davie Lab, University of Washington) for advice on recombinant expression in P. pastoris, Dr. Brett Kaiser and Dr. Clint Speigel (Stoddard Lab, FHCRC) for advice on protein purification, Tonibelle Gatbonton and Benjamin Newcomb (Bedalov lab, FHCRC) for help with the pilot library screen, Dr. Shlomo Handeli (Simon Lab, FHCRC) for help with the cellular toxicity assay and all members of the Vasioukhin lab for critical review of this manuscript.

Financial support: This study was supported by NCI grant R01 CA102365 and NTDF grant from FHCRC to VV. JC is a recipient of the NCI Chromosome Metabolism and Cancer Predoctoral Traineeship Award T32 CA09657.

References

- 1.Cancer Facts and Figures: American Cancer Society; 2008 2008.

- 2.The Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Test: Questions and Answers. US National Institutes of Health; 2007.

- 3.Early Prostate Cancer: Questions and Answers. US National Institutes of Health; 2007.

- 4.Vasioukhin V. Hepsin paradox reveals unexpected complexity of metastatic process. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1394–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.11.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford TJ, Tomlins SA, Wang X, Chinnaiyan AM. Molecular markers of prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2006;24:538–51. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magee JA, Araki T, Patil S, et al. Expression profiling reveals hepsin overexpression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5692–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhanasekaran SM, Barrette TR, Ghosh D, et al. Delineation of prognostic biomarkers in prostate cancer. Nature. 2001;412:822–6. doi: 10.1038/35090585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stamey TA, Warrington JA, Caldwell MC, et al. Molecular genetic profiling of Gleason grade 4/5 prostate cancers compared to benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2001;166:2171–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanimoto H, Yan Y, Clarke J, et al. Hepsin, a cell surface serine protease identified in hepatoma cells, is overexpressed in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2884–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zacharski LR, Ornstein DL, Memoli VA, Rousseau SM, Kisiel W. Expression of the factor VII activating protease, hepsin, in situ in renal cell carcinoma. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:876–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klezovitch O, Chevillet J, Mirosevich J, Roberts RL, Matusik RJ, Vasioukhin V. Hepsin promotes prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:185–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srikantan V, Valladares M, Rhim JS, Moul JW, Srivastava S. HEPSIN inhibits cell growth/invasion in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6812–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran P, Li W, Fan B, Vij R, Eigenbrot C, Kirchhofer D. Pro-urokinase-type plasminogen activator is a substrate for hepsin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30439–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchhofer D, Peek M, Lipari MT, Billeci K, Fan B, Moran P. Hepsin activates pro-hepatocyte growth factor and is inhibited by hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor-1B (HAI-1B) and HAI-2. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1945–50. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fear G, Komarnytsky S, Raskin I. Protease inhibitors and their peptidomimetic derivatives as potential drugs. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113:354–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbenante G, Fairlie DP. Protease inhibitors in the clinic. Med Chem. 2005;1:71–104. doi: 10.2174/1573406053402569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somoza JR, Ho JD, Luong C, et al. The structure of the extracellular region of human hepsin reveals a serine protease domain and a novel scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) domain. Structure. 2003;11:1123–31. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chirgadze NY, Sall DJ, Klimkowski VJ, et al. The crystal structure of human alpha-thrombin complexed with LY178550, a nonpeptidyl, active site-directed inhibitor. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1412–7. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans DM, Sloan-Stakleff K. Suppression of the invasive capacity of human breast cancer cells by inhibition of urokinase plasminogen activator via amiloride and B428. Am Surg. 2000;66:460–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt KN, Podda M, Packer L, Baeuerle PA. Anti-psoriatic drug anthralin activates transcription factor NF-kappa B in murine keratinocytes. J Immunol. 1996;156:4514–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raynaud F, Bauvois B, Gerbaud P, Evain-Brion D. Characterization of specific proteases associated with the surface of human skin fibroblasts, and their modulation in pathology. J Cell Physiol. 1992;151:378–85. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041510219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauvois B. Murine thymocytes possess specific cell surface-associated exoaminopeptidase activities: preferential expression by immature CD4-CD8- subpopulation. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:459–68. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauvois B, Sanceau J, Wietzerbin J. Human U937 cell surface peptidase activities: characterization and degradative effect on tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:923–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sameni M, Moin K, Sloane BF. Imaging proteolysis by living human breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2000;2:496–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGowen R, Biliran H, Jr, Sager R, Sheng S. The surface of prostate carcinoma DU145 cells mediates the inhibition of urokinase-type plasminogen activator by maspin. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4771–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertucci C, Domenici E. Reversible and covalent binding of drugs to human serum albumin: methodological approaches and physiological relevance. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:1463–81. doi: 10.2174/0929867023369673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wasan KM, Brocks DR, Lee SD, Sachs-Barrable K, Thornton SJ. Impact of lipoproteins on the biological activity and disposition of hydrophobic drugs: implications for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:84–99. doi: 10.1038/nrd2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boffito M, Back DJ, Blaschke TF, et al. Protein binding in antiretroviral therapies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:825–35. doi: 10.1089/088922203769232629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satonin DK, Coutant JE. Comparison of gas chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography for the analysis of probucol in plasma. J Chromatogr. 1986;380:401–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83670-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu CA, Tsujita M, Hayashi M, Yokoyama S. Probucol inactivates ABCA1 in the plasma membrane with respect to its mediation of apolipoprotein binding and high density lipoprotein assembly and to its proteolytic degradation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30168–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheetz MJ, Barnhart RL, Jackson RL, Robinson KM. MDL 29311, an analog of probucol, decreases triglycerides in rats by increasing hepatic clearance of very-low-density lipoprotein. Metabolism. 1994;43:233–40. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(94)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tardif JC, Gregoire J, Schwartz L, et al. Effects of AGI-1067 and probucol after percutaneous coronary interventions. Circulation. 2003;107:552–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047525.58618.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Equilibration time dependence of hepsin inhibition. Hepsin was incubated with indicated compounds (A - compound 3, B - compound 4, C - compound 5, D - compound 13) at their respective IC50 values or with buffer/solvent alone. Samples were withdrawn at 30, 60, 120 and 180 minutes and kinetic enzyme activity analyzed by the addition of substrate. Data are shown as percent inhibition relative to the respective buffer/solvent controls, incubated for the same amount of time.

Figure S2. Reversibility of hepsin inhibition. Hepsin was incubated with indicated compounds (A - compound 3, B - compound 4, C - compound 5, D - compound 13) at their respective IC50 values or with buffer/solvent control for 1 hour at room temperature. Samples were then diluted with buffer to the additional percentage indicated and kinetic enzyme activity analyzed by the addition of substrate. Data are shown as percent inhibition relative to the respectively diluted buffer controls.