Abstract

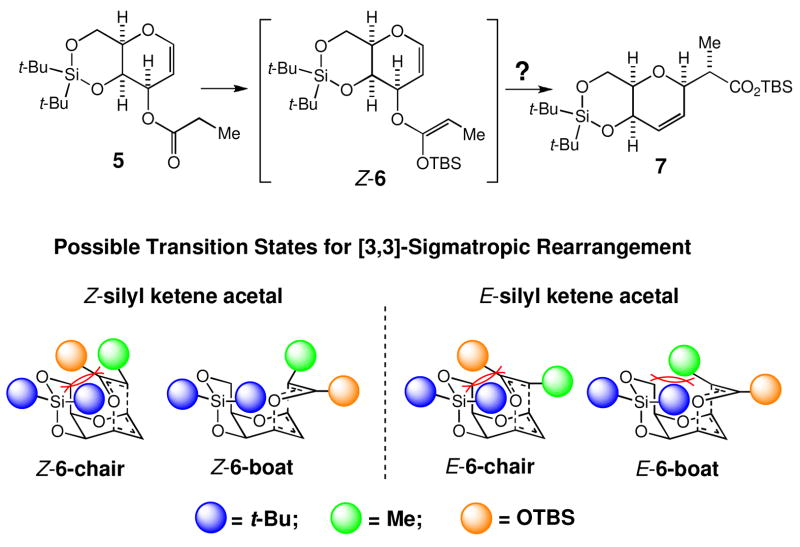

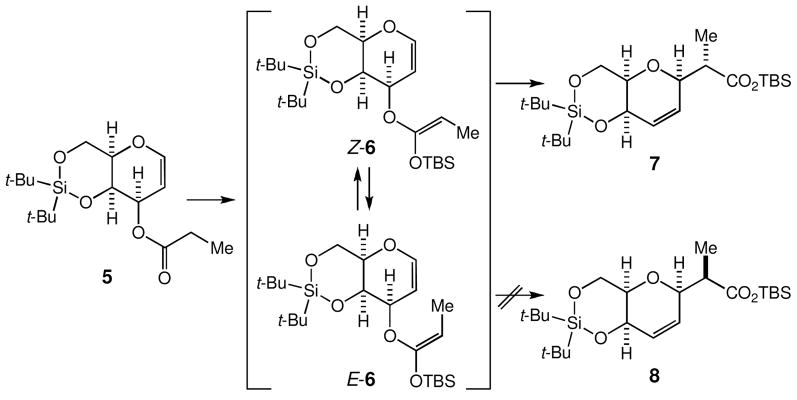

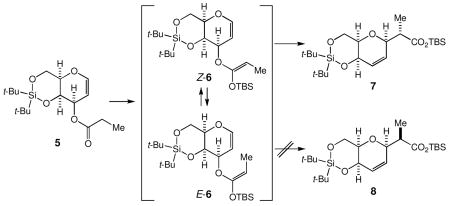

With focus on the steric effects present in the transition states for the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, the substrate 5 was designed to improve the overall stereoselectivity of the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement. Experimentally, it was found that: (1) only Z-6 rearranges to 7 at 80 °C and (2) E-6 isomerizes to Z-6 at 80 °C, thereby allowing to transform 5 into 7 in an almost quantitative yield. To illustrate the usefulness of this approach, two additional examples are given.

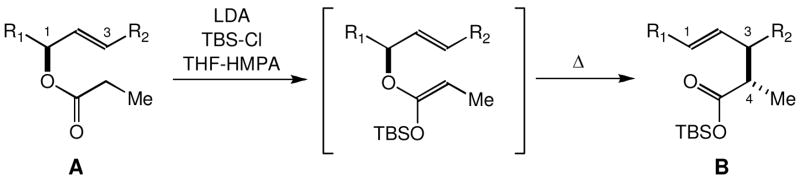

The Ireland-Claisen rearrangement is a versatile method to transfer the stereochemistry of a C-O bond into a C-C bond.1,2 As depicted in Scheme 1, this method consists of two synthetic operations, namely O-silyl ketene acetal formation, followed by thermally induced [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. Ireland demonstrated that Z- or E-selective O-silylation takes place on treatment of an ester with lithium-amide base in THF-HMPA or THF, respectively.3 Upon heating, the Z- or E-stereochemistry is relayed to the C4-stereochemistry in the product. It is generally agreed that the [3,3]-rearrangement proceeds through a chair-like transition state for acyclic systems, whereas the rearrangement proceeds through a boat-like transition state for pyranoid- and furanoid-glucals.2 Overall, the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement is effective to transform A into B in a stereo-controlled manner. However, it still remains a challenge to improve the overall stereoselectivity of this method.

Scheme 1.

The Ireland-Claisen rearrangement is depicted for the case where the O-silyl ketene acetal is formed under the Z-selective condition and the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement proceeds through a chair-like transition state.

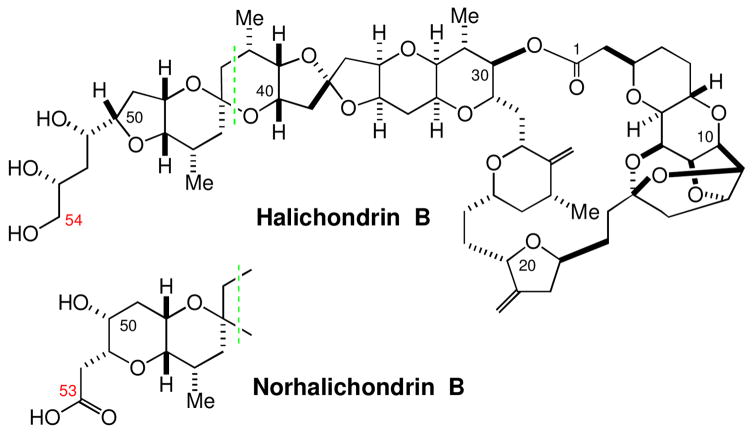

In the first generation synthesis of the marine natural products halichondrins (Scheme 2), 4 we relied on this synthetic method to construct the C27–C38 and C44–C53 building blocks of halichondrins (Scheme 3).5, 6, 7, 8 The overall stereoselectivity was approximately 8:1 for 1→3 and 5:1 for 1→4, respectively. In this letter, we report a new approach to perform this transformation in a completely-stereocontrolled manner.

Scheme 2.

Structure of halichondrin B and norhalichondrin B.

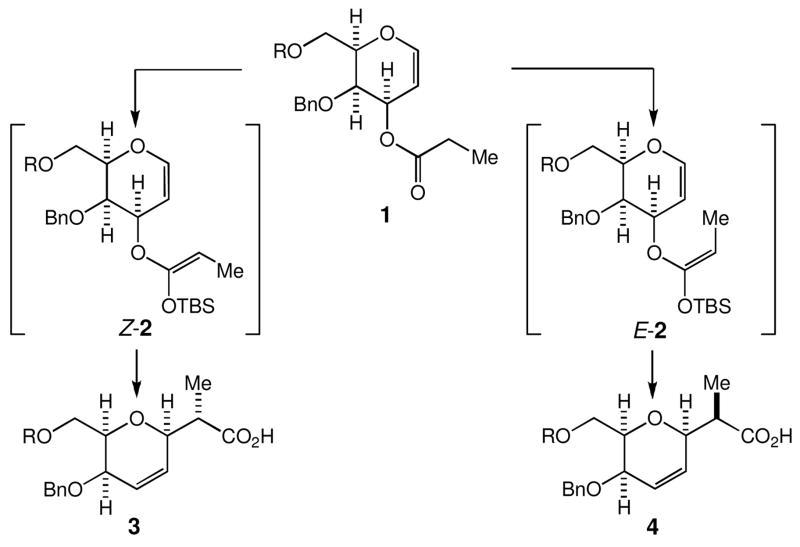

Scheme 3.

The Ireland-Claisen rearrangements used for the stereo-selective construction of two building blocks in the first generation synthesis of halichondrins. Carboxylic acids 3 and 4 were converted to the C27–C38 building block of the halichondrins and the C44–C53 and C44–C55 building blocks of the nor- and homo-halichondrins, respectively.7,8

The overall stereoselectivity of 1→3 and 1→4 (Scheme 3) was found to match roughly with the Z/E-ratio of O-silyl ketene acetals subjected to the Claisen rearrangement,7 indicating no obvious discrimination of the Z- over E-isomer at 80 °C in the step of [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. However, we wondered whether the activation energy for the thermally induced [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements could be affected with steric factors, resulting in an improvement in the overall stereochemistry of this process.9 Specifically, we focused on the steric destabilization present in the transition state for the Z- or E-O-silyl ketene acetal shown in Scheme 4. The E-O-silyl ketene acetal could rearrange through, in principle, either a boat-like or chair-like transition state, but both transition states appear to have a severe steric destabilization. Similarly, the Z-O-silyl ketene acetal could rearrange through either a boat-like or chair-like transition state. Interestingly, the chair-like transition state appears to have a severe steric destabilization, whereas the boat-like transition state appears to be free from such a steric destabilization. Thus, there is a possibility that the [3,3]-sigmatropic process might take place preferentially for the Z-O-silyl ketene acetal through the boat-like transition state, thereby resulting in an improvement in the overall stereoselectivity of this process.

Scheme 4.

Analysis of the steric destabilization in the chair- and boat-like transition states for the Z- and E-O-silyl ketene acetals derived from 5. In this analysis, t-Bu, Me, and OTBS are considered as sterically demanding groups, but the size of blue, green, or brown ball does not represent their relative steric-size.

In order to test this possibility, we synthesized the silylene 5 from commercially available D-galactal in two steps, (1) (t-Bu)2Si(OTf)2, py and (2) (EtCO)2O, DMAP, Et3N, in 91% overall yields in a 10-g scale. It is worthwhile to note that, unlike the acetonide case, 10 the silylene formation is completely selective for the C4 and C6 hydroxyl groups.

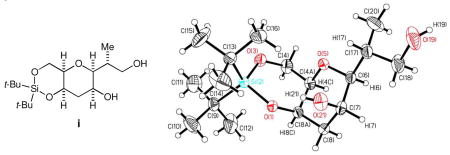

Under the conditions reported by Ireland (LHMDS, TBSCl, HMPA, THF, −78 °C), 5 was converted to the corresponding O-silyl ketene acetal 6, which was estimated as a 7.3:1 mixture of Z-6 and E-6 via 1H NMR analysis (Scheme 5). Upon heating at 80 °C in benzene for one day, this mixture furnished the carboxylate 7 as a single diastereomer in >85% yield, along with 5 and E-6 in a ca. 12% combined yield. The stereochemistry of 7 was unambiguously established via X-ray analysis on a derivative of the γ-lactone 9 shown in Scheme 6.11 We should make a comment on two experimental observations. First, the O-silyl ketene acetal recovered from the reaction was E-6, thereby indicating that the Claisen rearrangement took place through Z-6, but not through E-6. Second, the Me-stereochemistry of 7 indicated that the Claisen rearrangement proceeded exclusively via the boat-like transition state Z-6 boat.12

Scheme 5.

Stereospecific Ireland-Claisen rearrangement to transform 5 to 7.

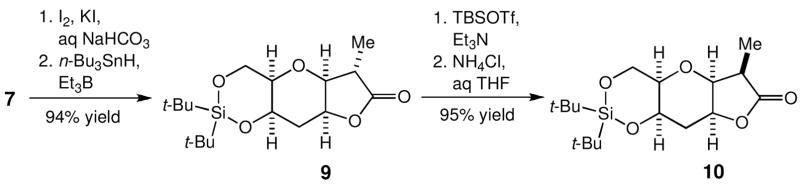

Scheme 6.

Inversion of the stereogenic center of secondary methyl group.

We then examined the possibility to isomerize E-6 into Z-6, desirably under the rearrangement condition. Wilcox and Babston reported a facile geometrical isomerism of O-silyl ketene acetals in the presence of trialkylammonium perchlorate in CDCl3.13,14 Being encouraged with this, we heated a 7.3:1 mixture of Z-6 and E-6 at 80 °C in benzene for 3 days and obtained virtually pure 7 in an almost quantitative yield, thereby demonstrating that E-6 did isomerize into Z-6 under the rearrangement condition. The O-silyl ketene acetal used was the crude product obtained via a standard aqueous workup of the silylation reaction.15 Thus, we speculate that the observed isomerization is thermally induced, although there is the possibility that a salt(s) contaminated in the crude silyl ketene acetal might have catalyzed the isomerization. For preparative purposes, this procedure now allows us to stereospecifically convert 5 into 7 in an almost quantitative yield.16

Unlike the case outlined in Scheme 3, the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of 5 does not give a direct access to the Me-diastereomer of 7. Therefore, we studied a method to convert 7 into its Me-diastereomer 8. With use of two standard synthetic operations, 7 was converted to the γ-lactone 9 in 94% overall yield (Scheme 6). Considering its cage-like structure, we anticipated that the protonation on the enolate of 9 should take place preferentially from its convex face. In practice, the enolate of 9 was first trapped as its TBS-silyl ether and desilylation in the presence of aqueous ammonium chloride, to yield exclusively 10 in 95% overall yield.

The example summarized in Scheme 5 demonstrates that the overall stereoselectivity of the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement can be improved by modulating sterically the activation energy for the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. Naturally, we were curious in testing this notion on other substrates. In this respect, the following two examples are instructive.

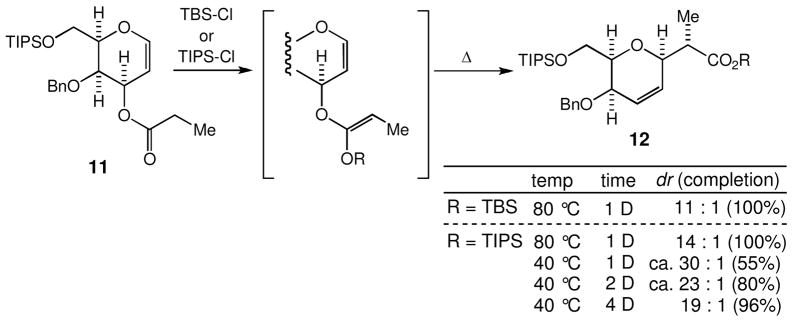

For the first example, we chose to use again the galactal template, but with a pattern of protecting groups different from 5. Upon heating at 80 °C in benzene, the O-silyl ketene acetal prepared with treatment of 11 with TBS-Cl gave a 11:1 mixture of 12 and its Me-diastereomer (Scheme 7). Interestingly, the O-silyl ketene acetal prepared with treatment of 11 with TIPS-Cl gave a 14:1 mixture of the two diastereomers, thereby showing that the steric bulkiness of the silyloxy group also has a noticeable effect. We then studied the rearrangement at a lower temperature (40 °C) and found that the diastereomeric ratio declined gradually from the day-one to the day-four. This time-course study suggested that (1) activation energy from Z-isomer to the product is smaller than that from E-isomer and (2) [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement proceeds via a boat-like transition state from the stereochemistry of 12. In addition, the observed overall stereoselectivity at 80 °C (14:1) vs. 40 °C (19:1) indicated that the E→Z isomerization takes place under the rearrangement condition at 40 °C.

Scheme 7.

The Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of the galactal with a pattern of protecting groups different from 5.

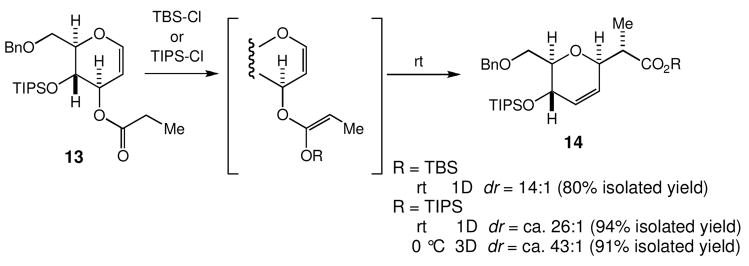

For the second example, we chose to use a substrate in the glucal series (Scheme 8).17 Unlike the galactal series, the Z/E-ratio at O-silylation was not reliably estimated, because the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement occured even at rt. The overall stereoselectivity from 13 to 14 was 14:1 via O-silylation with TBS-Cl. As noticed in the 11→12 case, the stereoselectivity was vastly improved via O-silylation with TIPS-Cl. Speculating that 11 and 13 may share the overall profiles of reactivity, i.e., (1) the Z-isomer rearranges faster than the E-isomer and (2) the E-isomer isomerizes to the Z isomer, we examined the possibility to improve the stereoselectivity by keeping the crude O-silyl ketene acetals at 0 °C; indeed, the transformation of 13 into 14 was achieved in 91% overall yield with the ca. 43:1 stereoselectivity.

Scheme 8.

The Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of a glucal.

In summary, we have demonstrated a valid approach to improve the overall stereoselectivity of the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement by sterically modulating the activation energy for the [3,3]-sigmatropic process. With this, the transformation of 5 into 7 was realized in a stereospecific manner in an almost quantitative yield. Following the routes previously established, 7 was converted into the two building blocks of halichondrins.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details, data of X-ray analysis, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra of key compounds (55 pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health (CA 22215) and to the Eisai Research Institute for generous financial support.

References

- 1.Ireland RE, Mueller RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:5897. doi: 10.1021/ja00765a079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For reviews, see: Ziegler FE. Chem Rev. 1988;88:1423.Enders D, Knopp M, Schiffers R. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1996;7:1847.Chai Y, Hong SP, Lindsay HA, McFarland C, Mclntosh MC. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:2905.Martin Castro AM. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2939. doi: 10.1021/cr020703u.

- 3.Ireland RE, Wipf P, Armstrong JD., III J Org Chem. 1991;56:650. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For the isolation of the halichondrins from a marine sponge Halichondria okadai Kadota, see: Uemura D, Takahashi K, Yamamoto T, Katayama C, Tanaka J, Okumura Y, Hirata Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:4796.Hirata Y, Uemura D. Pure Appl Chem. 1986;58:701.For isolation of the halichondrins from different species of sponges, see: Pettit GR, Herald CL, Boyd MR, Leet JE, Dufresne C, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Cerny RL, Hooper JNA, Rützler KCJ. Med Chem. 1991;34:3339. doi: 10.1021/jm00115a027.Pettit GR, Tan R, Gao F, Williams MD, Doubek DL, Boyd MR, Schmidt JM, Chapuis J-C, Hamel E, Bai R, Hooper JNA, Tackett LP. J Org Chem. 1993;58:2538.Litaudon M, Hart JB, Blunt JW, Lake RJ, Munro MHG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:9435.Litaudon M, Hickford SJH, Lill RE, Lake RJ, Blunt JW, Munro MHG. J Org Chem. 1997;62:1868.

- 5.For the synthetic work on the marine natural product halichondrins from this laboratory, see: Aicher TD, Buszek KR, Fang FG, Forsyth CJ, Jung SH, Kishi Y, Matelich MC, Scola PM, Spero DM, Yoon SK. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:3162.Choi H-w, Demeke D, Kang F-A, Kishi Y, Nakajima K, Nowak P, Wan Z-K, Xie C. Pure Appl Chem. 2003;75:1.Namba K, Jun HS, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7770. doi: 10.1021/ja047826b.Namba K, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15382. doi: 10.1021/ja055966v.Kaburagi Y, Kishi Y. Org Lett. 2007;9:723. doi: 10.1021/ol063113h.Zhang Z, Huang J, Ma B, Kishi Y. Org Lett. 2008;10:3073. doi: 10.1021/ol801093p. and references cited therein.

- 6.For synthetic work by Salomon, Burke, Yonemitsu, and Phillips, see: Kim S, Salomon RG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:6279.Cooper AJ, Pan W, Salomon RG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:8193. and the references cited therein.Burke SD, Buckanan JL, Rovin JD. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:3961.Lambert WT, Hanson GH, Benayoud F, Burke SD. J Org Chem. 2005;70:9382. doi: 10.1021/jo051479m. and the references cited therein.Horita K, Hachiya S, Nagasawa M, Hikota M, Yonemitsu O. Synlett. 1994:38.Horita K, Nishibe S, Yonemitsu O. Phytochem Phytopharm. 2000:386. and the references cited therein.Henderson JA, Jackson KL, Phillips AJ. Org Lett. 2007;9:5299. doi: 10.1021/ol702559e.

- 7.(a) Aicher TD, Buszek KR, Fang FG, Forsyth CJ, Jung SH, Kishi Y, Scola PM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:1549. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fang FG, Kishi Y, Matelich MC, Scola PM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:1557. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strictly speaking, 3 was converted to the C27–C38 building block of halichondrin B as well as homo- and nor-halichondrin Bs, whereas 4 was converted to the C44–C53 and C44–C55 building blocks of nor- and homo-halichondrin Bs, respectively.

- 9.For a relevant study, for example see: Wilcox CS, Babston RE. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:6636.

- 10.Acetonization of D-galactal ((MeO)2C(Me)2/PPTS) gave a 2:1 mixture of C4/C6- and C3/C4-acetonides.

-

11.An X-ray analysis was conducted on crystalline diol i (mp 143 °C) obtained on LiBH4-reduction of 9. X-ray crystal data for compound i: C17H34O5Si; MW=346.53; Monoclinic, space group P21 (No. 4), a = 9.1476(2) Å, b = 8.6362(1) Å, c = 12.8960(2) Å; α = 90, β= 105.592(1), γ = 90, V = 981.30(3) Å3, Z = 2, Dcal = 1.173 Mg/m3; independent reflections [R(int) = 0.0337]; refinement method, full-matrix least-squares refinement on F2; Goodness-of-fit on F2 = 1.020; final R indices [I > 2sigma(I)] R1 = 0.0359, wR2 = 0.0857.

- 12.Strictly speaking, 7 could arise through the chair-like transition state of E-6. However, this possibility is very unlikely, because E-6 was recovered and also because the E-enriched silyl ketene acetal did not give a higher yield of 7.

- 13.Wilcox CS, Babston RE. J Org Chem. 1984;49:1451. [Google Scholar]

- 14.For some relevant examples, see: Adam W, Wang X. J Org Chem. 1991;56:7244.Tanaka F, Node M, Tanaka K, Mizuchi M, Hosoi S, Nakayama M, Taga T, Fuji K. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:12159.

- 15.After O-silylation completed, the reaction mixture was poured onto hexanes. The organic layer was washed with water (5 times) and brine, dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated to afford the crude O-silyl ketene acetal.

- 16.This transformation was repeated in 20-gram scales by Dr. Chengguo Dong and Mr. Atsushi Ueda in this laboratories.

- 17.Several cases were reported on the Ireland-Claisen rearrangement of D-glucal derivatives, with the overall stereoselectivity varying from 2:1 to 6:1; see, Ireland RE, Wuts PGM, Ernst B. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:3205.Wallace GA, Scott RW, Heathcock CH. J Org Chem. 2000;65:4145. doi: 10.1021/jo0002801.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental details, data of X-ray analysis, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra of key compounds (55 pages). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.