Abstract

Background

Local production of IgA and IgE in the airways has been proposed to be an important event in both immune protection from pathogens and the pathogenesis of airway allergic diseases.

Objective

The objective of this study was to investigate the production of B cell-activating factor of the TNF family (BAFF), an important regulator of B cell survival and immunoglobulin class switch recombination, in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid after segmental allergen challenge (SAC) of allergic subjects.

Methods

SAC with saline or allergen was performed in 16 adult allergic subjects. BAL was performed at both saline-and allergen-challenged sites 20–24 hr after challenge. Concentrations of B cell-active cytokines including BAFF, IL-6 and IL-13 were measured using specific ELISA and cytometric bead array assays.

Results

BAFF protein was significantly elevated in BAL fluid after allergen challenge (53.8 pg/ml (0–407.4 pg/ml), p=0.001) compared with those at saline sites (0 pg/ml (0–34.7 pg/ml)). In the BAL fluid after allergen challenge, BAFF levels were significantly correlated with absolute numbers of total cells (r=0.779, p<0.001), lymphocytes (r=0.842, p<0.001), neutrophils (r=0.809, p<0.001) and eosinophils (r=0.621, p=0.010) but did not correlate with macrophages. Normalization to albumin indicated that BAFF production occurred locally in the airways. BAFF levels were also significantly correlated with other B cell-activating cytokines, IL-6 (r=0.875, p<0.001) and IL-13 (r=0.812, p<0.001).

Conclusion

The antigen-induced production of BAFF in the airway may contribute to local class switch recombination and immunoglobulin synthesis by B cells.

Keywords: Local immunoglobulin production, Segmental allergen challenge, BAFF, Allergic diseases, B cells, Eosinophils

INTRODUCTION

Allergic diseases are among the most common chronic inflammatory diseases worldwide.1 IgE has been associated with allergic diseases including asthma and rhinitis. Mast cells and basophils are key effector cells for IgE-mediated immune responses via cross-linking of their cell surface high affinity IgE receptor FcεRI.2, 3 After activation of cross-linking of FcεRI, mast cells and basophils release a wide variety of biological mediators including histamine, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, cytokines and chemokines.2, 3 Thus, IgE can trigger both immediate allergic reactions and late phase allergic reactions by the activation of mast cells and basophils.

Allergic reactions occur frequently in the mucosal tissues of the respiratory tract, skin and gut. In airway inflammatory diseases, local B cell class switch recombination (CSR) and synthesis of IgE and IgA can mediate activation of airway mast cells and eosinophils, respectively, in response to antigen exposure.4, 5 B cell clusters and IgA- and IgE-expressing B cells and plasma cells are found in the lamina propria of the nasal mucosa of patients with upper airways allergic disease.6 The levels of antigen-specific IgE are frequently found to be much higher in the airways and in the nasal mucosa than in the serum of individuals allergic to airborne allergens.7–10 Formation of IgE germline transcripts, which are biomarkers of the initial step of IgE CSR, is frequently found in the nasal mucosa of patients with allergic rhinitis, but usually only during the pollen season.6 IgE germline transcripts are also found in the bronchial mucosa of patients with atopic asthma and non atopic asthma but not in control subjects.11 Antigen specific IgE is significantly increased in BAL of asthmatic subjects after segmental allergen challenge (SAC).12, 13 Although it is now accepted that B cell accumulation, CSR and immunoglobulin production all occur locally in the airway,4, 5 the mechanism of local CSR and immunoglobulin production is not fully understood.

CSR is a process by which B cells shift from expression of the IgM H chain C region (Cμ) to another C region to make a new isotype of antibody. In general, CSR requires two signals.4, 5, 14 The first is normally through T cell cytokines including IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 and TGF-β which target specific CH genes for transcription. The second is delivered by the engagement of CD40 on B cells by its ligand, CD40 ligand, on activated T cells. B cell-activating factor of the TNF family (BAFF; also known as BLyS, TNFSF13B, TALL-1 and THANK) is a recently identified member of the TNF super family that plays important roles in B cell survival, proliferation and maturation.15, 16 Although CSR is generally thought to be highly dependent on the interaction of CD40 and CD40 ligand, it has been recognized that BAFF can also play a role as a second signal for CSR in the absence of T cells or CD40-dependent signaling.16, 17 BAFF binds to two high affinity receptors that are selectively expressed on B cells, including BAFF receptor (BAFF-R) and transmembrane activator and CAML interactor (TACI).16 BAFF-R is a potent regulator of mature B cell survival and IgE production by BAFF.18 TACI is critical for CSR and production of IgA immunoglobulins in humans.19 BAFF can also bind to a low affinity receptor, B cell maturation antigen (BCMA).16 Although BAFF is a critical factor for T cell independent immunoglobulin production, other cytokines are also required for CSR (e.g., IL-4 and IL-13 for IgE class switching). While BAFF has been recognized to mainly be a product of myeloid cells such as monocytes, dendritic cells (DCs) and neutrophils, non-lymphoid cell types also produce BAFF, including salivary gland epithelial cells, fibroblast-like synoviocytes and astrocytes.16, 17 Recently we have reported that BAFF is also produced by bronchial epithelial cells and nasal epithelial cells at a similar order of magnitude as that produced by myeloid cells.20, 21

Segmental allergen challenge (SAC) is widely used to study immune mechanisms of human allergic subjects in vivo and is a well known and relatively safe tool.22 In the present study, we investigated whether BAFF is induced by allergic reactions in human lower airways in vivo using SAC. We report here that BAFF is produced in the lower airway of allergic subjects following allergen exposure and the levels of production were highly correlated with the appearance of the other B cell activating cytokines, IL-6 and IL-13. These findings imply that exposure to antigen in the airway activates a process that stimulates the release of cytokines, including BAFF and others, that are known to promote CSR and immunoglobulin synthesis by B cells.

METHODS

Subjects and study protocol

Sixteen allergic subjects (9 males, 7 females) were recruited from the Johns Hopkins Asthma and Allergy Center. They ranged in age from 18 to 43 years (median, 33 years) and were classified as previously described based on history, allergy skin testing, lung function, and methacholine challenge.23 Details of subjects’ characteristics are included in Table I. All subjects signed informed consent, and the protocol and consent forms governing procedures for this study were approved by the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research. Bronchoscopy was performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and as reported in previous studies.12, 24, 25

The allergen selected for SAC was prioritized as 1.) ragweed, 2.) D. pteronyssinus, or 3.) D. farinae based on individual sensitivity. Allergens were selected to have low endotoxin content (range .125 – 25 endotoxin units/ml in undiluted stock preparations). The allergen concentration used for SAC was titrated for each individual based on allergen sensitivity to intradermal skin testing as previously described.24 Subjects were premedicated with 0.6 mg of atropine and 0.1 mg of fentanyl administered intravenously. After inhalation of nebulized 4% lidocaine, an Olympus BF10 fiberoptic bronchoscope (Olympic Corp., Lake Success, N.Y.) was inserted into the lower airways. Local anesthesia was supplemented with 2% lidocaine. A control sham challenge was performed by instilling 5 ml of normal saline into a subsegment of the lingula or right middle lobe. Antigen challenge was then performed by wedging a subsegment of the opposite lung (middle lobe or lingula) followed by instillation of 5 ml of ragweed (Greer Laboratories, Lenoir, NC), Dermatophagoides farinae (Greer Laboratories) or Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Greer Laboratories) antigen (Table 1). In two individuals, challenges were performed into wedged airway segments by 2 minute aerosols of normal saline or allergen (Table 1). After 20–24 hours, a second bronchoscopy was performed with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) at the sites of the normal saline and antigen challenges. BAL was performed with five, 20 ml aliquots of normal saline pre-warmed to 37°C. BAL fluid from each site was pooled and processed separately for cell, cytokine and albumin measurements. Blood samples (except in one patient) were collected at the time of the BAL after allergen challenge for cytokine and albumin measurements in the serum.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Subject | Disease | Age | Sex | Race | Allergen | Dose* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Allergic Asthma | 20 | Female | Cauc | RW | 0.03a × 0.5 |

| 2 | Allergic Asthma | 25 | Female | AA | RW | 0.03a × 25 |

| 3 | Allergic Asthma | 35 | Male | AA | RW | 5 × 0.1 |

| 4 | Allergic Asthma | 43 | Female | AA | RW | 5 × 0.1 |

| 5 | Allergic Asthma | 28 | Male | AA | RW | 5 × 0.1 |

| 6 | Allergic Asthma | 37 | Male | Cauc | DF | 5 × 0.03 |

| 7 | Allergic Rhinitis | 28 | Female | AA | RW | 5 × 2.5 |

| 8 | Allergic Asthma | 27 | Male | AA | DPT | 5 × 0.3 |

| 9 | Allergic Asthma | 33 | Male | Cauc | DPT | 5 × 0.3 |

| 10 | Allergic Asthma | 35 | Female | Cauc | DPT | 5 × 0.06 |

| 11 | Allergic Rhinitis | 43 | Female | Cauc | DPT | 5 × 0.13 |

| 12 | Allergic Asthma | 33 | Male | Cauc | DPT | 5 × 0.001 |

| 13 | Allergic Asthma | 33 | Male | AA | RW | 5 × 10 |

| 14 | Allergic Rhinitis | 43 | Female | AA | RW | 5 × 10 |

| 15 | Allergic Asthma | 18 | Male | AA | RW | 5 × 10 |

| 16 | Allergic Rhinitis | 42 | Male | AA | RW | 5 × 0.01 |

Cauc, Caucasian; AA, African American; RW, Amb a1 (Antigen E); DF, Der f1; DPT, Der p1.

Dose, volume (ml) × concentration (μg/ml) of specific allergen;

, volume delivered by aerosol.

Cell counts

The volume of fluid recovered from each 100 ml lavage specimen was recorded. Before centrifugation, aliquots of fluid were removed for measurement of cell counts with a hemocytometer; cell viability was determined by trypan blue-dye exclusion; and differential cell counts were obtained by a Diff-Quik stain (American Scientific Products, McGaw Park, Ill.) of cytocentrifuge preparations (Cytospin; Shandon Southern Instruments, Inc., Sewickley, Pa) as previously described.24 Total cells was calculated as volume of BAL fluid recovered × cells/ml by hemocytometer count. Total counts of each cell type were calculated as total cells × percent of each cell type determined by differential cell counts.

Soluble protein measurement

The concentrations of BAFF (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) albumin (Bethyl Laboratory, Montgomery, TX), IgA (Bethyl Laboratory) and sIgA (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH) in BAL fluids and in the serum were measured with specific ELISA kits. The minimal detection limits for these kits are 31 pg/ml, 6.25 ng/ml, 7.8 ng/ml and 22.2 ng/ml, respectively. The concentrations of IL-6, IL-13 and IgE in BAL fluids were measured using a cytometric bead array (CBA) human IL-6 Flex Set, CBA human IL-13 flex set and CBA human IgE flex set (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). In brief, 50 μl of the mixed capture beads and 50 μl of BAL fluid were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. After adding 50 μl of the PE detection reagent to the mixture and incubation for 2 hours at room temperature, the beads were then washed with the wash buffer and analyzed with a BD FACSArray Bioanalyzer (BD Biosciences). The CBA data was analyzed with FCAP Array software version 1.0.1 (BD Biosciences). The minimal detection limits are 5 pg/ml (IL-6), 5 pg/ml (IL-13) and 1 ng/ml (IgE).

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as the medians (range; minimum to maximum). Differences between groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test or the Mann-Whitney U-test. Correlations were assessed by using the Spearman’s rank correlation. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

To determine the relevance of BAFF expression in experimental allergic responses in the lower airway, BAL fluids were collected from twelve allergic asthma subjects, 8 males (7 African American and 5 Caucasian subjects) and four allergic rhinitis subjects, 1 male (3 African American and 1 Caucasian subjects) after challenge with allergen or saline. Subject characteristics are shown in Table I.

Inflammatory cell responses in BAL fluid

Recovery of BAL fluid did not differ between saline-challenged sites (median, 49%; 28–63%) and allergen-challenged sites (median, 42%; 16–79%) (Table E1). As we expected, SAC induced a vigorous inflammatory cellular response in allergic subjects (Table 2), as previously reported.12, 24–26 Total cell numbers were approximately 3-fold greater at allergen-challenged sites than saline sites. Most cells found at the saline-challenged sites were macrophages. At allergen-challenged sites, lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils were present in significant numbers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inflammatory cell responses in BAL fluid

| Saline | Allergen | P** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cells (106 cells) | 16.4* (10.4–42.0) # | 46.3 (11.9–270.0) | 0.001 |

| Macrophages (106 cells) | 13.6 (7.5–39.7) | 13.9 (5.6–67.0) | 0.510 |

| Lymphocytes (106 cells) | 1.4 (0.3–5.5) | 6.9 (1.5–30.3) | 0.001 |

| Neutrophils (106 cells) | 0.9 (0.0–7.3) | 5.3 (0.9–104.5) | 0.002 |

| Eosinophils (106 cells) | 0.1 (0.0–1.8) | 22.1 (0.2–141.5) | 0.001 |

median, #(range);

saline vs allergen.

Detection of BAFF in BAL fluid

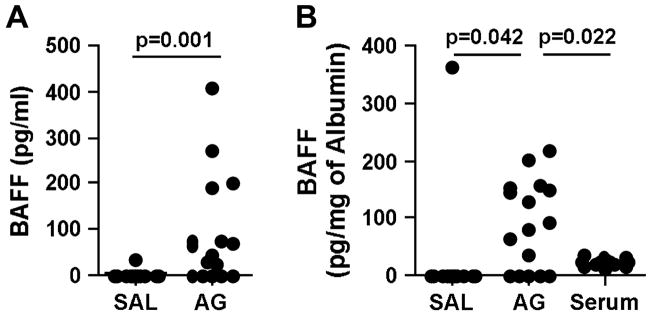

Shown in Fig. 1A are the ELISA results for BAFF using BAL fluids obtained 20–24 hours after segmental challenge. BAFF levels were below the limit of detection in most of the samples from saline sites with the exception of one patient (34.7 pg/ml). In the allergen-challenged sites, BAFF protein levels (median, 53.8 pg/ml; 0–407.4 pg/ml) were significantly increased compared to those at saline sites (p=0.001). We did not find any difference in this response between subjects with asthma or rhinitis or when using different allergens (RW or DPT) (Table E1).

Figure 1.

BAFF production in BAL fluid after SAC. (A) Measurement of BAFF in BAL fluids obtained 20–24 hours after segmental allergen challenge or saline challenge was performed using ELISA. (B) BAFF concentration in BAL and serum was normalized to the concentration of albumin. The mean concentration of BAFF in the serum was 710±280 pg/ml (mean±SD). SAL; saline, AG; antigen.

BAFF is known to circulate in the blood, and serum levels have been reported in the range of 500–1500 pg/ml.27, 28 To elucidate whether elevation of BAFF protein in BAL fluid after allergen challenge reflects local production in the airway or if it reflects plasma leakage, we measured the concentration of albumin and used it as a marker of plasma exudation. Albumin concentrations in BAL fluid were significantly increased after challenge (35 μg/ml (15–104 μg/ml) after saline challenge versus 370 μg/ml (43–3362 μg/ml) after antigen challenge, p=0.001) (Table E1). When we normalized the concentration of BAFF to the concentration of albumin in BAL and serum, the BAFF concentration in BAL fluid after allergen challenge (median, 87.4 pg/mg of albumin) was still significantly higher than in BAL fluid after saline challenge (median, 0 pg/mg of albumin, p=0.042, see Fig. 1B). BAFF normalized to albumin was also higher in the BAL of antigen-challenged sites when compared to levels in the serum (median, 24.7 pg/mg of albumin, p=0.022). This data suggests that BAFF is produced and/or released locally after allergen exposure in the airway even though some of the BAFF protein observed in the BAL after antigen challenge may appear as the result of vascular leakage.

Levels of BAFF correlate with allergen-induced inflammatory cells and cytokines

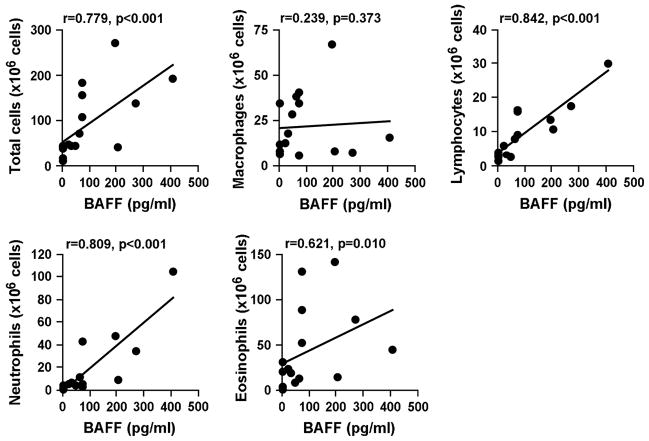

In the BAL fluid after allergen challenge, BAFF levels were strongly correlated with absolute numbers of total cells (r=0.779, p<0.001), lymphocytes (r=0.842, p<0.001), neutrophils (r=0.809, p<0.001) and eosinophils (r=0.621, p=0.010) (Fig. 2). No significant correlation was found between BAFF concentrations and macrophage numbers (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

BAFF levels correlated with allergen-induced influx of inflammatory cells. Differential cell counts were obtained using Diff-Quik staining of cytocentrifuge preparations. Correlations were assessed using the Spearman’s rank correlation.

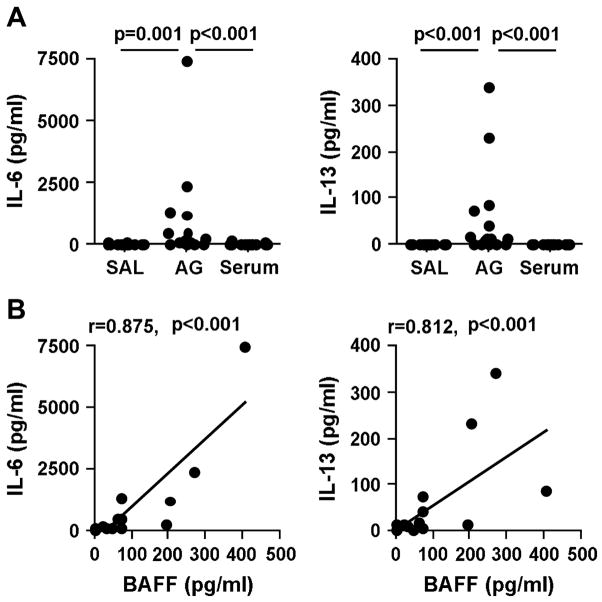

We also analyzed the concentrations of other B cell-activating cytokines, IL-6 and IL-13, in the BAL fluid and in the serum. Confirming previous reports,25, 29 we observed that the concentrations of IL-6 and IL-13 after allergen challenge were significantly increased in BAL fluid (IL-6; 88.4 pg/ml (9.9–7549 pg/ml), IL-13; 11.7 pg/ml (0–339.7 pg/ml)) when compared with saline challenge (IL-6; 4.2 pg/ml (1.2–54.1 pg/ml), IL-13; 0 pg/ml) or compared to levels in the serum (IL-6; 8.1 pg/ml (0–106.4 pg/ml), IL-13; 0 pg/ml) (Fig. 3A). Using BAL fluid data obtained from allergen-challenged segments only, we found that the levels of BAFF were strongly correlated with the levels of IL-6 (r=0.875, p<0.001) and IL-13 (r=0.812, p<0.001) (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

BAL levels of BAFF after allergen challenge were correlated with levels of cytokines. (A) Measurement of other B cell activators, IL-6 and IL-13, in BAL and in serum, was performed using CBA assays. (B) Correlations were assessed using the Spearman’s rank correlation. SAL; saline, AG; antigen.

Detection of immunoglobulins in BAL fluid

We also analyzed the concentrations of total immunoglobulins, IgA, sIgA and IgE, in the BAL fluid and in the serum. The concentrations of total IgA and total IgE after allergen challenge were significantly increased in BAL fluid (IgA; 22.6 μg/ml (7.1–345.1 μg/ml), p=0.002, IgE; 12.8 ng/ml (1.4–776.5 ng/ml), p=0.007) when compared with saline challenge (IgA; 6.3 μg/ml (2.5–15.1 μg/ml), IgE; 1.3 ng/ml (0–15.2 ng/ml)) (Fig. E1A and Table E1). In addition, the concentrations of IgA (r=0.887, p<0.001) and IgE (r=0.627, p=0.009) were strongly correlated with the level of BAFF in BAL fluid from allergen-challenged segments (Fig. E1B). However, when we normalized the concentration of immunoglobulins to the level of albumin in BAL and serum, the concentrations of IgA and IgE in BAL fluid after allergen challenge were not higher than in BAL fluid after saline challenge or in the serum (Fig. E1C). In addition, the concentration of sIgA was not elevated in BAL fluid from allergen-challenged segments (Fig. E1A).

DISCUSSION

It is now clear that antigen-specific B cells are activated and undergo CSR in the airways during allergic responses.4, 5 Thus, it becomes important to consider the role that local factors in the mucosa play in the recruitment, differentiation, activation, and survival of B lymphocytes. BAFF is an important regulator of B cell activation, proliferation, CSR and immunoglobulin production. This study provides the first demonstration that BAFF, as well as other B cell-activating cytokines, IL-6 and IL-13, was significantly increased in BAL fluid after SAC in allergic subjects (Fig. 1 and 3). The concentrations of BAFF detected in BAL fluid at allergen-challenged sites were highly correlated with the absolute numbers of recruited inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils, but BAFF was not correlated with the numbers of macrophages. The concentrations of antigen-induced BAFF were also correlated with the concentrations of other B cell active cytokines, IL-6 and IL-13 (Fig. 2 and 3).

Despite the generality that CSR is restricted to lymphoid organs, it is accepted that local immunoglobulin CSR and IgE production also occur in the airway.4, 5 It has been reported from many laboratories that IgE class switching and antigen specific IgE production occur in the nasal and airway mucosa of patients with allergic asthma and allergic rhinitis, although the mechanism is not fully understood.4, 6, 11, 12, 30–32 The Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 are well known to induce IgE production from B cells. It is well established that IL-4 and IL-13 are induced after SAC in allergic patients and that these cytokines are also induced ex vivo following allergen exposure of biopsy specimens obtained from allergic subjects.24, 25, 30 In this report we demonstrate that the concentrations of IL-13 in BAL fluid were significantly increased after SAC when compared with saline challenge (Fig. 3A). Although we did not assay IL-4 in the present study, previous studies by our group and others have shown that IL-4 is elevated following SAC.24, 33 While IL-4 and IL-13 can induce formation of the IgE germline transcript, which is a sterile product of the initial step of IgE CSR, these cytokines by themselves are not sufficient to induce DNA recombination and IgE synthesis in B cells. In addition to activation by IL-4 or IL-13, activation of CD40 by CD40 ligand on activated T cells and/or activation of BAFF-R/TACI by BAFF/APRIL are required to induce CSR and IgE production.4, 5, 16, 17 In the current study, we present the first evidence that BAFF is significantly increased in BAL fluid after SAC of allergic patients (Fig. 1A). To eliminate the possibility that the result merely reflects vascular leakage, we normalized values to the concentration of albumin as an indicator of plasma leak. Normalized BAFF concentrations in BAL fluids at allergen-challenged sites were still significantly higher than in BAL fluids of saline-challenged sites and were higher than normalized values in the serum (Fig. 1B) suggesting that BAFF is produced locally during experimental allergic reactions in the lower airway. These results do not totally eliminate the possibility that vascular leakage or active transport contribute to the increased appearance of BAFF in antigen-challenged airways, however. Importantly, the IgE class switch-inducing cytokine, IL-13, was also produced locally after allergen challenge and concentrations of IL-13 were strongly correlated with concentrations of BAFF (Fig. 3B). In addition, another B cell activator, IL-6, was also induced in the lower airway and concentrations were significantly correlated with BAFF (Fig. 3B). Collectively, this data suggests that local production of B cell stimulating cytokines, BAFF, IL-13 and IL-6, may play a role in local B cell responses, immunoglobulin isotype class switching and immunoglobulin production in the lower airway of allergic inflammatory diseases.

We did not identify the origins of BAFF production in the lower airway. It is well known that BAFF is produced by monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils and epithelial cells from several tissues including lungs, nasal airways and sinus tissue and tonsils.16, 17, 20, 21, 34,35 Several groups have reported that T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes are capable of producing BAFF in several conditions, although the level of expression is rather weak compared to that of myeloid cells.16, 36, 37 Our present study showed that BAFF concentrations in BAL fluid after SAC were positively correlated with the numbers of lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils but not macrophages. This suggests that infiltrating neutrophils and lymphocytes may play a greater role in BAFF production in the airway after allergen challenge than resident macrophages (Fig. 2). In the current study, we showed that eosinophils were the most highly accumulated cells in BAL fluid after allergen challenge, which agrees with previous studies showing that the absolute number of eosinophils was enhanced more than 250 fold (Table 2). However, our previous studies with purified peripheral blood eosinophils indicated that neither resting eosinophils nor eosinophils primed with IL-5, GM-CSF, sIgA or IFN-β made BAFF in vitro.21 Previous studies have shown that eosinophils isolated from BAL are phenotypically distinct from those primed by cytokines in vitro and the possibility remains that infiltrating eosinophils may make BAFF in the lower airways.38, 39 Another possible source of BAFF observed in the lower airway in the present study is dendritic cells. DCs are well known to produce BAFF17 and a recent study has shown that DC subsets, both myeloid DCs and plasmacytoid DCs, are accumulated in BAL fluid after SAC.40 Importantly, DCs, especially plasmacytoid DCs, are well known as type I IFN producing cells. Type I IFNs, IFN-α and IFN-β, strongly activate DCs, monocytes, macrophages and epithelial cells to produce BAFF, indicating that alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells may also play an important role in the local production of BAFF, although they are not elevated in BAL after allergen challenge.17, 20 This suggests that accumulation and activation of DCs in the lower airway may be one of the key events that induce BAFF production from resident and infiltrating cells. Recently, we have reported that BAFF is elevated in nasal polyp tissue from patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, and expression of BAFF is correlated with B cell markers. This suggests that overproduction of BAFF in nasal polyps may contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, perhaps via expansion and activation of B cells.21 We have also shown that BAFF producing cells in the upper airway include mucosal epithelial cells and unidentified infiltrating cells in the lamina propria.21 This would support the suggestion that both infiltrating cells in BAL and tissue epithelial cells may produce BAFF in the lower airway. In either case, the correlation of local BAFF production with the influx of inflammatory cells suggests that BAFF production is an integral part of the inflammatory response driven by allergen. Future studies will be required to determine the precise nature of the BAFF-producing cells in the lower airway after allergen challenge.

The current finding, that BAFF is elevated in the lower airway after allergen challenge of allergic subjects, has implications for the local activation of immunoglobulin production and class switching, as has been proposed to occur in allergic diseases in the airways.4, 5, 12, 31, 32 We therefore analyzed the concentrations of immunoglobulins, total IgA, total IgE and sIgA in this study. Although normalized IgA and IgE concentrations in BAL fluids at allergen-challenged sites were not higher than in BAL fluids of saline-challenged sites or in the serum, the absolute concentrations of IgA and IgE were significantly increased in BAL fluids after allergen challenges (from 4–10 fold Fig. E1). In addition, the concentration of sIgA, which is known as the mucosal immunoglobulin and is not found circulating at meaningful levels in the periphery, was not elevated in BAL fluids from allergen-challenged segments (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that the elevation of IgA and IgE in BAL fluids during the short 24 hr period of time after allergen challenge is primarily mediated by vascular leak.

Previous studies have shown that antigen specific IgE is elevated in BAL fluid within 24 hr after allergen challenge using the same challenge protocol.12, 13 Thus it is quite possible that local antigen specific IgE production by allergen is regulated by the local production of BAFF while total IgE levels largely reflect leak during the 24 hr post challenge period. Earlier studies41 showed that B cell CSR requires substantially longer than 24 hr, suggesting that local production of antigen specific IgE in the BAL is mediated by B cells that have already undergone class switching, such as those that are frequently found in airway mucosa of allergic subjects.4, 11, 32 Mucosal sIgA, which was not elevated in BAL fluid in this study, has to be transported by the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor in the epithelium after production of dimeric IgA by plasma cells.42 Thus it is reasonable to expect that the production of sIgA requires a longer time than the production of monomeric IgA. It is probable that newly class switched B cells produce local IgA and IgE at a time later than 24 hr post challenge. Local production of BAFF and IL-13 might induce both IgE production in pre-switched B cells and IgE CSR in naive B cells. The direct relevance of BAFF production and B cell response in the airway is worthy of future investigation using an extended challenge protocol.

In summary, we report here that BAFF is up-regulated in the airway of allergic subjects following allergen exposure. The concentration of BAFF was significantly higher in BAL at the allergen-challenged site than in the serum after normalization to serum albumin, suggesting that BAFF production occurs locally within the airways. BAFF levels at allergen-challenged sites were highly correlated with levels of IL-13 and IL-6. Our findings indicate that BAFF and other B cell stimulating cytokines are produced locally in the airway after exposure to antigen and may contribute to local B lymphocyte responses in airway inflammatory disease and in host defense.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH grants, R01 HL068546, R01 HL078860, 1R01 AI072570 and R01 AI063184 and by a grant from the Ernest S. Bazley Trust.

Abbreviations

- BAFF

B cell-activating factor of the TNF family

- CSR

class switch recombination

- SAC

segmental allergen challenge

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- CBA

cytometric bead array

Footnotes

Clinical implications: Local production of BAFF may have either a protective or pathogenic role in immunity or allergic diseases, respectively.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pearce N, Ait-Khaled N, Beasley R, Mallol J, Keil U, Mitchell E, et al. Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Thorax. 2007;62:758–66. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.070169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prussin C, Metcalfe DD. 5 IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:S450–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawakami T, Galli SJ. Regulation of mast-cell and basophil function and survival by IgE. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:773–86. doi: 10.1038/nri914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiset PO, Cameron L, Hamid Q. Local isotype switching to IgE in airway mucosa. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:233–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gould HJ, Takhar P, Harries HE, Durham SR, Corrigan CJ. Germinal-centre reactions in allergic inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:446–52. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takhar P, Smurthwaite L, Coker HA, Fear DJ, Banfield GK, Carr VA, et al. Allergen drives class switching to IgE in the nasal mucosa in allergic rhinitis. J Immunol. 2005;174:5024–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tse KS, Wicher K, Arbesman CE. IgE antibodies in nasal secretions of ragweed-allergic subjects. J Allergy. 1970;46:352–7. doi: 10.1016/0021-8707(70)90086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Small P, Barrett D, Frenkiel S, Rochon L, Cohen C, Black M. Local specific IgE production in nasal polyps associated with negative skin tests and serum RAST. Ann Allergy. 1985;55:736–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakajima S, Gillespie DN, Gleich GJ. Differences between IgA and IgE as secretory proteins. Clin Exp Immunol. 1975;21:306–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merrett TG, Houri M, Mayer AL, Merrett J. Measurement of specific IgE antibodies in nasal secretion--evidence for local production. Clin Allergy. 1976;6:69–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1976.tb01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takhar P, Corrigan CJ, Smurthwaite L, O’Connor BJ, Durham SR, Lee TH, et al. Class switch recombination to IgE in the bronchial mucosa of atopic and nonatopic patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peebles RS, Jr, Liu MC, Adkinson NF, Jr, Lichtenstein LM, Hamilton RG. Ragweed-specific antibodies in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids and serum before and after segmental lung challenge: IgE and IgA associated with eosinophil degranulation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:265–73. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson DR, Merrett TG, Varga EM, Smurthwaite L, Gould HJ, Kemp M, et al. Increases in allergen-specific IgE in BAL after segmental allergen challenge in atopic asthmatics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:22–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.1.2010112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oettgen HC. Regulation of the IgE isotype switch: new insights on cytokine signals and the functions of epsilon germline transcripts. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:618–23. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider P, MacKay F, Steiner V, Hofmann K, Bodmer JL, Holler N, et al. BAFF, a novel ligand of the tumor necrosis factor family, stimulates B cell growth. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1747–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackay F, Silveira PA, Brink R. B cells and the BAFF/APRIL axis: fast-forward on autoimmunity and signaling. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litinskiy MB, Nardelli B, Hilbert DM, He B, Schaffer A, Casali P, et al. DCs induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching through BLyS and APRIL. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:822–9. doi: 10.1038/ni829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castigli E, Wilson SA, Scott S, Dedeoglu F, Xu S, Lam KP, et al. TACI and BAFF-R mediate isotype switching in B cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:35–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castigli E, Wilson SA, Garibyan L, Rachid R, Bonilla F, Schneider L, et al. TACI is mutant in common variable immunodeficiency and IgA deficiency. Nat Genet. 2005;37:829–34. doi: 10.1038/ng1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato A, Truong-Tran AQ, Scott AL, Matsumoto K, Schleimer RP. Airway epithelial cells produce B cell-activating factor of TNF family by an IFN-beta-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2006;177:7164–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato A, Peters A, Suh L, Carter R, Harris KE, Chandra R, et al. Evidence of a role for B cell-activating factor of the TNF family in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1385–92. 92e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Julius P, Lommatzsch M, Kuepper M, Bratke K, Faehndrich S, Luttmann W, et al. Safety of segmental allergen challenge in human allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:712–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu MC, Bleecker ER, Lichtenstein LM, Kagey-Sobotka A, Niv Y, McLemore TL, et al. Evidence for elevated levels of histamine, prostaglandin D2, and other bronchoconstricting prostaglandins in the airways of subjects with mild asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:126–32. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu MC, Proud D, Lichtenstein LM, Hubbard WC, Bochner BS, Stealey BA, et al. Effects of prednisone on the cellular responses and release of cytokines and mediators after segmental allergen challenge of asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:29–38. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.116004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang SK, Xiao HQ, Kleine-Tebbe J, Paciotti G, Marsh DG, Lichtenstein LM, et al. IL-13 expression at the sites of allergen challenge in patients with asthma. J Immunol. 1995;155:2688–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bochner BS, Hudson SA, Xiao HQ, Liu MC. Release of both CCR4-active and CXCR3-active chemokines during human allergic pulmonary late-phase reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:930–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsushita T, Hasegawa M, Matsushita Y, Echigo T, Wayaku T, Horikawa M, et al. Elevated serum BAFF levels in patients with localized scleroderma in contrast to other organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:87–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Migita K, Abiru S, Maeda Y, Nakamura M, Komori A, Ito M, et al. Elevated serum BAFF levels in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:586–91. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Virchow JC, Jr, Walker C, Hafner D, Kortsik C, Werner P, Matthys H, et al. T cells and cytokines in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after segmental allergen provocation in atopic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:960–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cameron L, Hamid Q, Wright E, Nakamura Y, Christodoulopoulos P, Muro S, et al. Local synthesis of epsilon germline gene transcripts, IL-4, and IL-13 in allergic nasal mucosa after ex vivo allergen exposure. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:46–52. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.107398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.KleinJan A, Vinke JG, Severijnen LW, Fokkens WJ. Local production and detection of (specific) IgE in nasal B-cells and plasma cells of allergic rhinitis patients. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:491–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15.11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ying S, Humbert M, Meng Q, Pfister R, Menz G, Gould HJ, et al. Local expression of epsilon germline gene transcripts and RNA for the epsilon heavy chain of IgE in the bronchial mucosa in atopic and nonatopic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:686–92. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batra V, Musani AI, Hastie AT, Khurana S, Carpenter KA, Zangrilli JG, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentrations of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1, TGF-beta2, interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 after segmental allergen challenge and their effects on alpha-smooth muscle actin and collagen III synthesis by primary human lung fibroblasts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:437–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato A, Schleimer RP. Beyond inflammation: airway epithelial cells are at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:711–20. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu W, He B, Chiu A, Chadburn A, Shan M, Buldys M, et al. Epithelial cells trigger frontline immunoglobulin class switching through a pathway regulated by the inhibitor SLPI. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:294–303. doi: 10.1038/ni1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huard B, Arlettaz L, Ambrose C, Kindler V, Mauri D, Roosnek E, et al. BAFF production by antigen-presenting cells provides T cell co-stimulation. Int Immunol. 2004;16:467–75. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darce JR, Arendt BK, Chang SK, Jelinek DF. Divergent effects of BAFF on human memory B cell differentiation into Ig-secreting cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:5612–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroegel C, Liu MC, Hubbard WC, Lichtenstein LM, Bochner BS. Blood and bronchoalveolar eosinophils in allergic subjects after segmental antigen challenge: surface phenotype, density heterogeneity, and prostanoid production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;93:725–34. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(94)90252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sedgwick JB, Calhoun WJ, Vrtis RF, Bates ME, McAllister PK, Busse WW. Comparison of airway and blood eosinophil function after in vivo antigen challenge. J Immunol. 1992;149:3710–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bratke K, Lommatzsch M, Julius P, Kuepper M, Kleine HD, Luttmann W, et al. Dendritic cell subsets in human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after segmental allergen challenge. Thorax. 2007;62:168–75. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.067793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Claassen JL, Levine AD, Buckley RH. Recombinant human IL-4 induces IgE and IgG synthesis by normal and atopic donor mononuclear cells. Similar dose response, time course, requirement for T cells, and effect of pokeweed mitogen. J Immunol. 1990;144:2123–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cerutti A. The regulation of IgA class switching. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:421–34. doi: 10.1038/nri2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.