Abstract

Decades of research have documented in school-aged children a persistent difficulty apprehending an overarching biological concept that encompasses animate entities like humans and non-human animals, as well as plants. This has led many researchers to conclude that young children have yet to integrate plants and animate entities into a concept LIVING THING. However, virtually all investigations have used the word “alive” to probe children’s understanding, a term that technically describes all living things, but in practice is often aligned with animate entities only. We show that when “alive” is replaced with less ambiguous probes, children readily demonstrate knowledge of an overarching concept linking plants with humans and non-human animals. This work suggests that children have a burgeoning appreciation of this fundamental biological concept, and that the word “alive” paradoxically masks young children’s appreciation of the concept to which it is meant to refer.

Keywords: conceptual development, children, folkbiology, animacy, science education

The relation between a word and the concept to which it refers lies at the very heart of successful communication. While often taken for granted, we heavily rely on the shared alignment of words and concepts between speaker and hearer. For example, a hearer will only be able to correctly attribute new information that they hear about “dogs” to all dogs if the word “dog” and concept DOG are aligned. But this alignment is not always perfect. On the one hand, it may be responsive to the context or mode of communication. It is well known that context is an important part of interpretation (Grice, 1957; Levinson, 1983; Sperber & Wilson, 1995; among many others). For example, in an engineering context, “fluid” maps to a concept including both liquids and gases, while in common parlance, it would likely be understood to map to liquids only. Beyond context, there may also be problems with the concept-word mapping itself. Hearers may simply lack the underlying concept corresponding to a particular word, for example, abstract concepts like JUSTICE or ATOM. They may map the word to a different concept than the one intended by the speaker. Or they may have the relevant concept firmly in place, but have not yet aligned it with the corresponding word.

The discussion above is more than hypothetical, as misalignments between words and concepts have real consequences for children’s learning. In this paper we focus on a particularly important example, the relation between the word “alive” and the concept LIVING THING – a core biological concept that encompasses animate entities like humans and non-human animals, as well as plants. Decades of research have documented children’s difficulty in tasks designed to elicit this concept, and in particular their difficulty judging plants to be alive. This difficulty has often been taken as evidence that children do not yet have a grasp of the underlying concept Unmasking Children’s Concept of Living Things 4 LIVING THING, and that it remains elusive for them well into their primary school years (Carey, 1985; Hatano, Siegler, Richards, Inagaki, Stavy, & Wax, 1993; Klingberg, 1952; Klingensmith, 1953; Laurendeau & Pinard, 1962; Piaget, 1929; Russell & Dennis, 1939; Slaughter, Jaakkola, & Carey, 1999). In contrast, we suggest an alternative interpretation: it is not that this concept eludes children, but rather that they have failed to align the word “alive” with it. We propose that this misalignment arises due to the ambiguity of the word “alive,” which often maps to an animate interpretation in colloquial speech.

In the current study, we pursue this proposal, probing children’s concept LIVING THING under conditions designed to alleviate some of this ambiguity. In Experiment 1, we seek to alleviate the ambiguity by manipulating the context of presentation, while in Experiment 2, we do so by manipulating the wording of the test question itself. In examining the relation between children’s underlying concept and the words used to probe it, this study serves to highlight the powerful links between language and conceptual representations. A large body of research into children’s appreciation of the concept LIVING THING has primarily relied on a categorization task that elicits judgments on the life status of a series of entities, both living and non-living. In this task, based on work by Piaget (1929) and standardized by Laurendeau and Pinard (1962), life-status judgments are elicited using the word “alive,” as in: “Are X’s/Is the X (the entity) alive?” (Anggoro, Waxman, & Medin, 2008; Carey 1985; Hatano, et al., 1993; Richards & Siegler, 1984; among others). Because this task has been the metric against which children’s appreciation of the concept LIVING THING is measured, and because this concept is so fundamental to science education, the evidence merits close examination.

Unmasking Children’s Concept of Living Things 5

In classic work on this topic, Piaget (1929) described children as “animistic,” documenting in children as old as 12 years of age a pervasive tendency to deny that plants are alive, but to attribute life status to certain non-living objects (typically those that apparently move on their own) (see also Klingberg, 1952; Klingensmith, 1953; Laurendeau & Pinard, 1962; Russell & Dennis, 1939). Difficulty establishing the scope of the concept has been documented more recently in various populations (e.g., Anggoro, Waxman, & Medin, 2008; Carey, 1985; Opfer & Siegler, 2004; Richards & Siegler, 1984 for American children; Stavy & Wax, 1989 for Israeli children; Hatano, et al., 1993 for Japanese, American, and Israeli children). In general, these studies have underscored that children accurately attribute life status to animate entities, and are often adept at denying life status to nonliving entities. However, plants, being inanimate living things, have presented a particular challenge.

Children’s persistent difficulty is especially striking in light of evidence that even 4- and 5-year-olds can successfully identify the set of all living things -- including plants but excluding non-living entities -- when they are queried about biological properties other than “alive” (e.g., Anggoro, 2006; Backscheider, Schatz, & Gelman, 1993; Hatano, et al., 1993; Inagaki & Hatano, 1996; Opfer & Siegler, 2004; Springer & Keil, 1989, 1991; Waxman, 2005). Anggoro, Waxman and Medin (2008) illustrate this paradox. Children were asked to sort a series of cards depicting both living and non-living entities based on various predicates, including “is X alive,” “can X grow,” and “can X die.” Despite their successful categorization of all and only living things when prompted with the predicates “grow” and “die,” even 9- to 10-year-olds had more difficulty, and often excluded plants when prompted with the term “alive”.

Interestingly, then, although children do systematically apply certain predicates (e.g., “die”, “grow”) to humans, non-human animals, and plants, they have not mapped the word “alive” to it. Anggoro and her colleagues (2008) further show that this difficulty may be particularly pronounced in English-speaking populations, as Indonesian children were significantly more likely to include plants along with animate entities in their “alive” categorization. This result is attributed to differences in the naming practices in English and Indonesian for biological entities, suggesting a crucial role for language in the acquisition of biological concepts.

Focusing in on language, certain investigators have noted that children’s performance in the “alive” categorization task may be explained in part by their failure to interpret the word “alive” as adults do (Carey, 1985; Nguyen & Gelman, 2002; Piaget, 1929; Slaughter, Jaakkola, & Carey, 1999). Perhaps these studies are best interpreted as probing children’s interpretation of the word “alive,” and not their appreciation of an overarching concept linking all living things (Carey, 1985). Despite this suggestion for a more nuanced view of previous results, children’s persistent difficulty is more often taken as evidence that they “…simply do not understand that both animals and plants are living things (i.e., that they belong to the same category), and that children therefore…have difficulty finding a reasonable referent for the word ‘alive.’” (Slaughter, Jaakkola, & Carey, 1999, p. 79).

We propose that children do have burgeoning knowledge of an overarching concept linking humans, non-human animals, and plants, but use of the word “alive” masks their appreciation of it. “Alive” in English is ambiguous; it does not uniquely or even primarily map onto the Western science-inspired biological interpretation that is the focus of research on this topic. While it technically applies to humans, non-human animals, and plants, in practice its use is often aligned with animate beings only, thus excluding plants. Its entry in Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary illustrates this well. Among the 6 definitions listed, the primary definition, “having life,” seems apt because it picks out all (and only) living things. But this definition is immediately qualified with “not dead or inanimate,” thus explicitly excluding inanimates and therefore plants. This clearly reveals the tension between the technical meaning of “alive” and a more colloquial animate sense. The other Merriam-Webster entries underscore this animate meaning, as they generally relate to liveliness (“look alive,” “his face came alive at the mention of food”) or degree of activity (“streets alive with traffic,” “keep hope alive”).

Of course, we are not suggesting that children learn word meanings from dictionary definitions. Nonetheless, these entries are telling because they likely reflect something about adult usage, and therefore provide a glimpse of the cues to meaning that adults provide spontaneously, and unwittingly, to children. As children seek to establish the meaning of “alive,” therefore, they are likely to encounter a plethora of evidence for its sense that is aligned with animacy: a corpus analysis of child-directed speech suggests this is indeed the case (Leddon, Waxman, & Medin, 2007). The fact that “alive” is often used in this animate sense may be related to children’s difficulty including plants when questioned about this concept. Young children appear to map “alive” to the concept ANIMATE, instead of the concept LIVING THING. This observation would also explain why children tend to accurately attribute life status to animate entities, and deny it to nonliving things, but have difficulty with inanimate living things like plants.

In this paper we pursue the possibility of this misalignment between the word “alive” and the underlying concept to which it refers. To foreshadow, we show that young children can indeed integrate plants along with animate entities into an overarching concept LIVING THING, but that the word “alive” paradoxically masks their appreciation of the concept to which it is meant to refer.

Experiment 1

We have proposed that the word “alive,” and its close alignment to animacy, interferes with children’s ability to access the concept LIVING THING that it is intended to uncover. Children may nonetheless have access to another sense of “alive” that maps to the more inclusive biological concept. Perhaps children’s performance in previous studies simply reflects a failure on their part to realize that the scientific meaning of ‘alive’ was the meaning intended. If this is the case, and if children are indeed influenced by the context in which a task is presented, then it should be possible to highlight this more inclusive biological meaning. To test this possibility, we set an explicitly scientific context to highlight the more inclusive biological sense of the word “alive”. Our hypothesis is that if children have access to this alternative, more inclusive interpretation of “alive”, then they should successfully categorize plants along with the animate entities.

Method

Participants

Children were recruited from a large public magnet school in Chicago, IL, that draws from throughout the city to achieve racial and ethnic diversity (at the time of testing, the student population was 40.7% Black, 18.6% Hispanic, 17.0% White, 15.1% Asian, 8.2% Multi-Racial, .5% Native American). The mandate of this magnet school is not to select for particular aptitudes among students (e.g., math, performance arts), but rather to achieve a racial and ethnic diversity that goes beyond the diversity of neighborhood schools. Forty-four children participated: 14 4- to 5-year-olds (M = 5.21, SD = .56; 7 female, 7 male), 15 6- to 7-year-olds (M = 6.69, SD = .33; 7 female, 8 male), and 15 9- to 10-year-olds (M = 9.97, SD = .28; 10 female, 5 male).

Procedure

Children participated in a short testing session at their school. As the experimenter led the child to the testing area, she explicitly focused the child’s attention on science, explaining “…today we are going to talk about science. I just love science; it was always one of my favorite subjects and I still love learning about it. Do you like science?” She went on to ask what the child had been learning in science class lately, whether they had ever looked through a telescope or a microscope, and if they had ever done a science experiment.

Older children readily engaged in this conversation, describing their current science activities, which typically included cell biology (learning and diagramming parts of cells, etc.). Perhaps not surprisingly, the youngest children were often unsure what science was. For them, the experimenter followed up with a conversation about the sun, moon, planets, etc., explaining they would learn about these things in science someday. In all cases, an attempt was made to steer the conversation away from explicit discussions of living things, to avoid revealing the intent of the study or otherwise influencing children’s subsequent performance.

After the warm-up, the experimenter introduced the categorization task. It was explicitly described as an activity “about science.” Children were presented with 17 laminated cards, each depicting a photograph of an object on a white background (see Appendix for all entities depicted). To begin, the experimenter explained that the child would be asked to make two piles, “…one pile for everything that’s alive, another pile for everything that’s not alive.” After shuffling the cards, the experimenter presented them one at a time, asking “What’s this?” Then, using the name provided by the child, the experimenter asked, “Are X’s alive?” Each card was placed in the pile designated by the child. The experimenter noted the child’s responses; items judged alive and not alive were scored as 1 and 0, respectively. We then calculated each child’s mean response for the animate, plant, and non-living targets.

Results

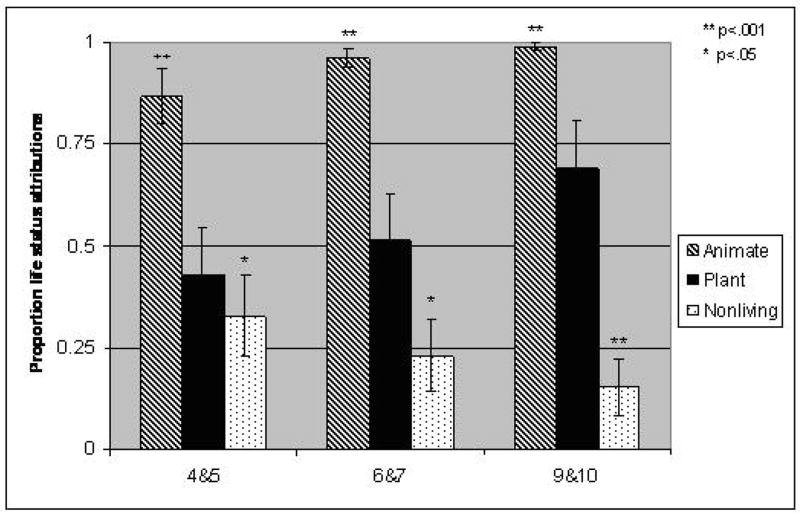

Although children were presented with the term “alive” within an explicitly scientific context, their performance nevertheless mirrored decades of previous research, revealing children’s persistent difficulty including plants (Figure 1). We conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) using category (3: animate, plant, nonliving1) as a within-participants factor, age (3: 4 to 5 years, 6 to 7 years, 9 to10 years) as a between-participants factor, and children’s responses as a dependent variable. This analysis revealed only a main effect for category, F(2, 82) = 46.59, p < .001. Pairwise comparisons revealed that children included animates in their categorization at a greater rate than plants, and included plants at a greater rate than nonliving things, both p’s < .001.

Figure 1.

Experiment 1. Proportion of life status attributions in each category, as a function of age.

Comparisons to chance performance augment this interpretation. As predicted, children at all ages had no difficulty attributing life status to animate entities. Performance in this category differed from chance levels at every age, all p’s < .001. Also as predicted, children reliably denied life status to non-living things; performance in this condition differed from chance levels at every age, all p’s < .05. However, when it came to judging the life status of plants, children at all ages performed at the chance level. Importantly, then, even the 9- to 10- year-olds failed to include plants in their categorization of things that are “alive.”

Discussion

Placing the “alive” categorization task explicitly within the context of science did not alter the general pattern found in decades of previous research. Indeed, children as old as 9 to 10 years of age failed to reliably attribute life status to plants. Therefore children’s difficulty was not ameliorated with a manipulation of context, and they continued to misalign “alive” with the concept ANIMATE.

Of course, it is possible that our manipulation failed to signal a scientific context or mode of construal in children. This point is well-taken, especially for the younger children, who often did not know what science was. But the older children readily discussed their current science activities, and often gave detailed accounts of learning about cell biology, including parts of plant and animal cells. Even these children, who clearly engaged in a scientific conversation and discussed issues relevant to living things immediately prior to the categorization task, largely failed to include plants in their categorization. It is clear, therefore, that children have failed to align the word “alive” with a concept that corresponds to the biological concept including animate entities as well as plants. What is less clear is whether children might be more likely to tap into an overarching concept of living things in a categorization task that did not include the ambiguous term “alive.” This question is examined directly in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2

To examine whether children have an overarching biological concept of humans, nonhuman animals, and plants as living things, we probed children’s knowledge but avoided the word “alive” entirely. This experiment tests the hypothesis that children indeed appreciate the relevant concept, but their apprehension of it is masked by the word “alive,” which is fraught with ambiguity. To do so, we conducted a categorization task, substituting the semantically equivalent “living thing” for “alive”. Although this may appear on the surface to be a more technical and demanding concept, “living thing” has few (if any) alternative senses, and no senses that systematically exclude plants. Using this term also allowed us to directly probe for children’s knowledge of the overarching abstract concept, previously hinted at with children’s performance on tasks questioning other biological properties (like “grow” or “die”). We reasoned that if children do appreciate an overarching concept that includes plants as well as animate entities, then they should be more likely to show it here, when “alive” is avoided. In short, they should be more likely to attribute life status to plants, and to do so at an earlier age.

Method

Participants

Ninety children participated, from the same school as Experiment 1: 30 4-to 5-year-olds (M = 5.18, SD = .59; 14 female, 16 male), 29 6- to 7-year-olds (M = 6.90, SD = .53; 17 female, 12 male), and 31 9- to10-year-olds (M = 9.81, SD = .40; 19 female, 12 male).

None of the children had participated in Experiment 1.

Procedure

The method mirrored that of Experiment 1, except that there was no scientific discussion preceding the categorization task. Children were led to a quiet testing area in their school and immediately introduced to the categorization task, with no specific preceding context set. The categorization question itself was re-phrased “Are X’s living things?”.

Results

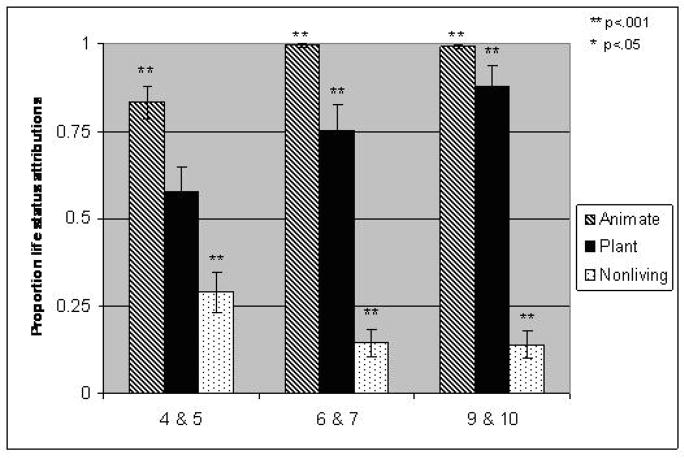

When asked about “living things,” children demonstrate a very different, and more precocious, appreciation of the overarching biological concept and of the place of plants within it (Figure 2). An ANOVA revealed a main effect of category, F(2, 174) = 210.82, p < .001, and a marginal effect of age, F(2, 87) = 2.98, p = .056, both of which were mediated by a category by age interaction, F(4, 174) = 7.36, p < .001. Post hoc analyses indicate that this interaction stemmed primarily from developmental differences in children’s attribution of life status to plants. Pairwise comparisons revealed that 4- to 5-year-olds and 6- to 7-year-olds were both more likely to include animates than plants in their categorization, both p’s < .01, and also more likely to include plants than non-living entities, both p’s < .001. In contrast, 9- to 10- year old children were just as likely to include plants as animates in their categorization, ns; and their tendency to include nonliving things was reliably lower than each, both p’s < .001.

Figure 2.

Experiment 2. Proportion of life status attributions in each category, as a function of age.

Comparisons to chance levels of responding are also revealing. As in Experiment 1, children at all ages readily attributed life status to animate entities, and denied life status to nonliving things; performance in these categories differed from chance levels at every age, all p’s < .001. However, children’s attribution of life status to plants was more precocious than in Experiment 1. While 4- to 5-year-olds attributed life status to plants at chance levels, by age 6- to 7, children attributed life status to plants at a rate greater than chance, p = .001, as did 9- to 10- year-olds, p < .001.

Discussion

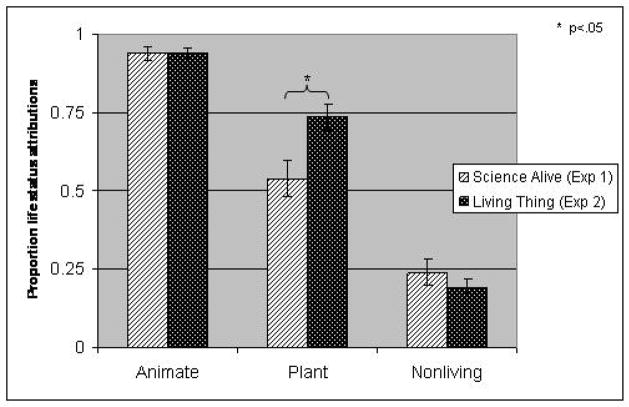

Children’s attributions of life status when queried about “living things” indeed revealed a relatively early appreciation of a core biological concept that includes plants as well as animate entities. While children categorizing based on “alive” never attributed life status to plants at a rate greater than chance, children categorizing based on “living thing” reliably attributed life status to plants by age 6 to 7, and distinguished plants from nonliving entities at age 4 to 5. This constitutes support for the hypothesis that the ambiguous “alive” is aligned with the concept ANIMATE, and not the concept LIVING THING. It therefore serves to mask children’s appreciation of this core biological concept. If this hypothesis is correct, then children should readily attribute life status to animate entities and deny it to nonliving things in both Experiments 1 and 2, but they should be more likely to attribute life status to plants in Experiment 2, when the ambiguous term “alive” was avoided, than in Experiment 1. In a final analysis, we tested this hypothesis directly in a series of planned comparisons based on an ANOVA using category (3) as a within-participants factor, and age (3) and experiment (2) as between-participants factors (Figure 3). As predicted, there were no reliable differences in attributions of life status to animates (for Experiment 1, M = .94, for Experiment 2, M = .94, ns) or to nonliving things (for Experiment 1, M = .24, for Experiment 2, M = .19, ns). In contrast, performance on plant did differ across the two experiments (for Experiment 1, M = .54, for Experiment 2, M = .74, p < .01). This analysis therefore confirms children’s greater tendency to include plants when categorizing based on “living thing” as compared to “alive,” suggesting an animacy-aligned interpretation of “alive.”

Figure 3.

Experiments 1 and 2 compared. Proportion of life status attributions in each category across experiments.

General Discussion

These experiments reveal that the word “alive” paradoxically masks young children’s burgeoning appreciation of the concept to which it is meant to refer. This is an important finding because decades of research demonstrating children’s difficulty apprehending a biological concept including all and only living things have heavily relied on this term. We have documented that the word “alive” itself actually interferes with their ability to access the very concept that it is intended to uncover. Moreover, when children are probed with the semantically equivalent, but less ambiguous, “living thing”, they are more likely to attribute life status to plants, and to do so at an earlier age.

The very fact that we observe this misalignment with the word “alive” is telling. Integrating plants into the concept LIVING THING is clearly difficult for young children, and simply replacing the word “alive” with a less ambiguous probe does not ameliorate this difficulty entirely. On the contrary, even in the current study where children were probed with “living thing”, it was not until 6 to 7 years of age that they reliably attributed life status to plants. In contrast, their success including animals and humans, even at the youngest ages, suggests a privileged place for animate beings in this category. This finding converges with previous work dating back to Piaget, and highlights the central role animacy plays in children’s concept of living things. Broadening the scope of the concept to include plants is likely no simple task for young children. Moreover, the ambiguity of the term “alive” and it close alignment to animacy represents an added challenge. Nevertheless, the results of Experiment 2 show that children can overcome this challenge, and demonstrate burgeoning knowledge of a concept that includes plants as well as animate entities when probed with the less ambiguous “living thing.” Indeed we suspect that subsequent research will reveal other contexts beyond the ones tested here in which this capacity will come forward; Linguistic manipulations are likely to be just one means of revealing children’s appreciation of the concept including only and all living things. It will be important in future work to also explore non-linguistic means of highlighting this category. These findings underscore the importance of considering the relation between words and concepts, especially if our goal is to discover the underlying conceptual representations of young children whose interpretation of words may not always straightforwardly map to the meaning adults intend. This work also has implications for science education. Because successful communication between teachers and students relies on shared word meanings, it is important to characterize not only the scientific concepts children bring to the classroom, but how children encode these concepts in words.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes for Health (R01 HD41653) and the National Science Foundation (BCS 0132469) to the second and third authors. The authors wish to express their gratitude to Flo Anggoro, Andrzej Tarlowski, Sara Unsworth, Patricia Hermann, Jessica Umphress, Melissa Luna, Will Bennis, and Olivier LeGuen for discussion of this work, and especially to Jennifer Woodring for contributions every step along the way. We also thank the principal, teachers, and students at Walt Disney Magnet School.

Appendix

Complete list of stimuli.

| Item | Category |

|---|---|

| Person | Animate |

| Bear | |

| Squirrel | |

| Blue jay | |

| Trout | |

| Bee | |

| Worm | |

| Maple Tree | Plant |

| Cranberry Bush | |

| Dandelion | |

| Sun | Non-Living |

| Clouds | |

| Water | |

| Rock | |

| Bicycle | |

| Scissors | |

| Pencil |

These entities correspond to the entities used in previous research (Anggoro, 2005; Anggoro, Waxman, & Medin, 2008). They were selected to represent a variety of life forms. For example, in addition to the human there are 3 mammals, 4 non-mammals (selected again for their variety: a bird, a fish, an insect, an invertebrate), 3 diverse plants, and 4 non-living natural kinds as well as 3 artifacts.

Footnotes

Preliminary analyses of both Experiments 1 and 2 revealed no differences within animates, within plants, or within nonliving things, and therefore we collapsed across these to test our hypotheses.

References

- Anggoro FK. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Northwestern University; 2006. Naming and acquisition of folkbiologic knowledge: Mapping, scope ambiguity, and consequences for induction. [Google Scholar]

- Anggoro FK, Waxman SR, Medin DL. Naming practices and the acquisition of key biological concepts: Evidence from English and Indonesian. Psychological Science. 2008;19(4):314–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backscheider AG, Schatz M, Gelman SA. Preschoolers’ ability to distinguish living kinds as a function of regrowth. Child Development. 1993;64:1242–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Carey S. Conceptual change in childhood. Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Grice P. Meaning. The Philosophical Review. 1957;66:377–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hatano G, Siegler RS, Richards DD, Inagaki K, Stavy R, Wax N. The development of biological knowledge: A multi-national study. Cognitive Development. 1993;8:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki K, Hatano G. Young children’s recognition of commonalities between animals and plants. Child Development. 1996;67:2823–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg G. The distinction between living and not living among 7–10-year-old children, with some remarks concerning the so-called animism controversy. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1952;90:227–238. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1957.10533019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingensmith SW. Child animism: What the child means by “alive”. Child Development. 1953;24:51–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1953.tb04715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurendeau M, Pinard A. Causal thinking in the child. New York: International Universities Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Leddon EM, Waxman SR, Medin DL. Talking about living things: What children learn about biological concepts in everyday conversations. Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development Biennial Meeting; Boston, MA. 2007. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Levinson SC. Pragmatics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen SP, Gelman SA. Four and 6-year-olds’ biological concept of death: The case of plants. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2002;20:495–513. [Google Scholar]

- Opfer JE, Siegler RS. Revisiting preschoolers’ living things concept: A microgenetic study of conceptual change in basic biology. Cognitive Psychology. 2004;49:301–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. In: The child’s conception of the world. Tomlinson J, Tomlinson A, translators. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co; 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Richards DD, Siegler RS. The effects of task requirements on children’s life judgments. Child Development. 1984;55:1687–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Russell RW, Dennis W. Studies in animism: I. A standardized procedure for the investigation of animism. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1939;55:389–400. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter V, Jaakkola R, Carey S. Constructing a coherent theory: Children’s biological understanding of life and death. In: Siegal M, Peterson C, editors. Children’s understanding of biology and health. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber D, Wilson D. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. 2. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Springer K, Keil F. On the development of biologically specific beliefs: The case of inheritance. Child Development. 1989;60:637–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]