Leukemia treatment reveals safer side of γ-secretase inhibitors

γ-secretase inhibitors inhibit Notch, a transmembrane receptor which drives many cases T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL)—but there are safety concerns with such drugs. A combination treatment involving γ-secretase inhibitors and glucocorticoids could provide a more effective and safer approach.

A targeted combination therapy described in this issue of Nature Medicine may greatly improve outcome in individuals with a common childhood blood cancer: T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL)1.

The therapy relies on the combination of a γ-secretase inhibitor with a glucocorticoid, dexamethasone. The γ-secretase inhibitor targets Notch1, a transmembrane cell surface receptor that regulates normal T cell development2; activating mutations in the gene encoding NOTCH1 cause more than half of TALL cases3. Dexamethasone counteracts lethal gut toxicity induced by the γ-secretase inhibitor. The authors outline how the combination therapy induces apoptosis in T-ALL cells—in T-ALL cell lines, primary human T-ALL cells and in xenografts of such T-ALL cell lines in mice—to a much greater extent than either dexamethasone or the γ-secretase inhibitor alone1 (Fig. 1).

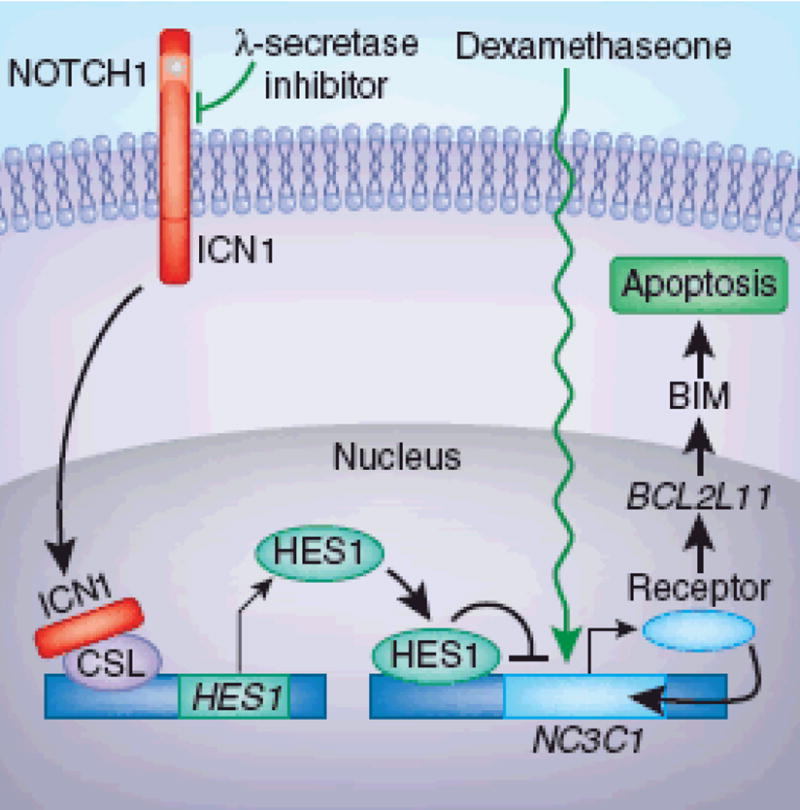

Figure 1. Combined treatment of NOTCH-positive T-ALL with a γ-secretase inhibitor and dexamethasone.

In untreated T-cells with mutant NOTCH (yellow dot), ICN1 released by γ-secretase associates with the transcription factor CSL and upregulates expression of the NOTCH target HES1. HES1 binding to the promoter of the NC3C1 gene inhibits its expression and results in insufficient production of the encoded glucocorticoid receptor- rendering these cells resistant to treatment with dexamethasone. Treatment with γ-secretase inhibitor and deamethasone prevents the release of ICN and CSL remains associated with a repressor complex, inhibiting HES1 expression. The inhibitor thereby restores autoinduction of the glucocorticoid receptor in the presence of dexamethasone and activates expression of its target genes, including BCL2L11. Increased amount of the proapoptotic BIM protein induces apoptosis, which eliminates the NOTCH-activated T-cells.

The approach, if they can be translated to people, might have benefits over current treatment of T-ALL, which accounts for 15% of childhood cases and 25% of adult cases of ALL4- a disease that affects approximately 5,000 people each year in the United States. Current multiagent chemotherapy regimens cure about 85% of children with T-ALL but only 50% of adults with T-ALL, and side effects are substantial5. The prognosis of adult patients has remained poor partly as a result of unfavorable genetic features of the leukemia as compared to those in children5.

NOTCH1 is a 2-chain molecule that, upon interaction of its extracellular domain with ligands of the Delta-Serrate-Lag 2 family, activates the intramembrane presenilin/γ-secretase protease complex that liberates the intracellular domain ICN1 of NOTCH1 from the lipid bilayer. After translocation to the nucleus, the ICN1 associates with the transcription factor CSL6 and activates the transcription of a set of target genes including the proliferation-promoting oncogene MYC. Although MYC upregulation contributes to NOTCH1-induced cellular transformation, experimental evidence suggests that the participation of additional responder genes is required in this process5. The introduction of activated NOTCH1 alleles into mouse bone marrow leads to the development of T-ALL7. This finding suggests that NOTCH1 activation is also an aspect of the human T-ALL disease process. This hypothesis is further supported by the observation that activated NOTCH1 is essential for maintaining the transformed state of the human malignant cells8.

Real et al.1 started their investigation by testing the hypothesis that T-ALL cell lines with activated NOTCH1 are resistant to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis due to their aberrant NOTCH1 signaling. Indeed, the cells showed minimal loss of viability after treatment with dexamethasone or GSI alone but were highly sensitive to the combined treatment. The authors show that the direct target of activated NOTCH1, the inhibitory transcription factor HES1, binds to the promoter of the gene NR3C1, which encodes the glucocorticoid receptor, thereby inhibiting its expression. Treatment with inhibitor enhanced NR3C1 expression and activity, which up-regulates the expression of its known target, the proapoptotic gene BCL2L11, resulting in apoptosis (Figure 1).

How does dexamethasone reverse GSI-induced intestinal toxicity in mice? GSI causes severe intestinal secretory metaplasia as a result of marked increase in goblet cell differentiation9 and arrested cell proliferation in the intestinal crypts. The tumor suppressor gene Klf4, which encodes a Kruppel-like transcription factor, normally regulates goblet cell differentiation10. Again, the authors show that increased HES1 expression in GSI-treated mice suppressed Klf4 expression directly by binding to the Klf4 promoter1 (Figure 1). Subsequent transcription profiling revealed that the intestines of mice treated with GSI and dexamethasone expressed more Ccnd2, a cell cycle regulator, than did that of mice treated with GSI alone. The authors provide evidence that the dexamethasone-induced expression of Ccnd2, at least in part, protects the mice from GSI-induced goblet cell metaplasia, though its observed effect on Klf4 downregulation is indirect1.

The known toxicity of dexamethasone treatment includes conditions such as osteopenia, hypertension and muscle atrophy; however, the potential effects of long-term inhibition of γ-secretase remain unknown. The enzyme γ-secretase targets more than 30 physiologically important transmembrane proteins, including the amyloid precursor protein involved in Alzheimer disease11. Given that there are at least 6 different γ-secretase complexes in humans, subtype-specific inhibitors may be developed that have less broad side effects12.

Clinical trials of GSI have been hindered by the considerable gastrointestinal problems experienced by the participants12. Therefore, it will be necessary to determine whether GSI/dexamethasone combination therapy is as safe in humans as it appears to be in mice. No doubt it will take time to determine the optimal safe dosage for treatment; Real et al. report that in a small number of their mice, the combined treatment had to be stopped due to excessive weight loss1. The combination treatment also increased lymphoid atrophy in the thymus and spleen, thereby potentially diminishing normal immunity.

Despite the promise of this approach for NOTCH-1 activated T-ALL, not all patients with this condition would be expected to respond. Eight percent of T-ALL samples harbor mutations in or show homozygous deletion of FBW7, a gene that encodes a ubiquitin ligase responsible for NOTCH1 ICN1 turnover. T-ALL cell lines carrying such mutations are resistant to GSI treatment13.

The findings of Real et al. may have broader implications, as NOTCH1 signaling is involved in many cancers14. By inference, the combination therapy might also be beneficial for solid tumors with aberrant NOTCH1 signaling. Likewise, GSI inhibits the production of amyloidogenic β-amyloid peptides involved in Alzheimer disease, and this work make provide new ways to treating that condition.

The new finding will initiate a flurry of research activity to further validate the combination therapy in additional preclinical studies1. Provided that the outcome will be positive, the approach will be ready to move into phase 1 trials.

References

- 1.Real PJ, et al. Nat Med. 2009;15:50–58. doi: 10.1038/nm.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabher C, von Boehmer H, Look AT. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:347–359. doi: 10.1038/nrc1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weng AP, et al. Science. 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrando AA, et al. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Lancet. 2008;371:1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsieh JJ, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:952–959. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pear WS, et al. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2283–2291. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang MY, Xu L, Shestova O, Histen G. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3181–3194. doi: 10.1172/JCI35090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milano J, et al. Toxicol Sci. 2004;82:341–358. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz JP, et al. Development. 2002;129:2619–2628. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolia A, De Strooper B. Semin Cell Dev Biol. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.10.007. published online. (31 October 2008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staal FJT, Langerak AW. Haematologica. 2008;93:493–497. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neil J, et al. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Li Y, Banerjee S, Sarkar FH. Cancer Lett. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.030. published online. (3 December 2008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]