The increasing use of Response to Intervention (RTI) for determining whether children qualify as learning disabled is due in large measure to the recognition that instruction plays a major role in determining the learning trajectory of individual children. In fact, it is now widely acknowledged that many students currently identified as learning disabled would not have been identified if instruction had been appropriately targeted and responsive (Clay, 1987; Denton & Mathes, 2003; Lyon, Fletcher, Fuchs, & Chhabra, 2006; Scanlon, Vellutino, Small, Fanuele & Sweeney, 2005; Snow, Burns & Griffin, 1998; Vellutino et al., 1996). Further, at least one study has documented a decline in special education classification rate after a tiered approach to interventions, a common RTI model, was implemented (O’Connor, Fulmer, Harty, & Bell, 2005).

Much of the research on RTI focuses heavily on evaluating children’s response to instruction while focusing little, if at all, on the instruction itself. Indeed, a major concern in many RTI studies is the incidence of false positives (i.e., cases where the assessments inaccurately identify a child as potentially learning disabled) and false negatives (i.e., cases where the assessments inaccurately identify a child as non-learning disabled), both of which raise the important question of what kinds of additional measures can be added to the prediction equations to reduce prediction errors. However, it is widely accepted that student achievement is determined in large part by the characteristics and qualities of instruction. Indeed, a central premise of RTI approaches is the need to insure that learning difficulties are not the result of inadequate instruction (Fuchs & Fuchs, 1998; Fuchs, Fuchs, & Speece, 2002; Vaughn, Linan-Thompson, & Hickman, 2003). Therefore, in this paper, we more fully explore the influence of instruction on children’s risk status. We focus, in particular, on classroom instruction as this is the critical first tier in most RTI models. Very little research has addressed either the characteristics of classroom instruction that serve to reduce the incidence of early reading difficulties or the potential effectiveness of professional development (PD) for classroom teachers in helping to reduce the incidence of early reading difficulties.

Thus, in this study, we analyzed the effects of PD for classroom teachers on the literacy skills of children who were deemed to be at risk of experiencing difficulties in early reading acquisition and we carefully investigated the characteristics of the instruction they offered both before and after participating in PD. Our design allowed us to investigate major premises of RTI models that are not often evaluated: 1) that the quality of the first tier of intervention (the classroom level) is a major determinant of children’s ongoing risk status; and 2) that PD for classroom teachers can effectively reduce the number of at risk children who continue to be at risk at the end of the school year. We also compared the effects of PD alone to the effects of small group intervention provided directly to at risk children and to the combination of both small group intervention and PD for classroom teachers.

Despite the relative lack of attention to the characteristics of classroom instruction in the RTI literature, in the broader education literature there has been growing interest in documenting instructional characteristics and their relationship to student achievement. There is now substantial documentation that variability in student outcomes is more closely associated with “natural” variability among classroom teachers than it is with variability between and among instructional programs (e.g., Bond & Dykstra, 1967; Tivnan & Hemphill, 2005). Moreover, several studies have documented substantial variability in the effectiveness of the early literacy instruction provided by classroom teachers (Foorman & Schatschneider, 2003; Pressley et al., 2001; Scanlon & Vellutino, 1996; Taylor, Pearson, Clark, & Walpole, 2000). Thus, although it has been well documented that certain characteristics of the child place him or her at risk for experiencing early reading difficulties (e.g., Fletcher et al, 1994; Stanovich & Siegel, 1994; Vellutino et al, 1996), it is also clear that characteristics of classroom instruction are powerful determinants of whether a child will experience such difficulties (Scanlon & Vellutino, 1996; 1997; Snow & Juel, 2005).

If RTI is to realize its promise, it is critical that more emphasis be placed on understanding the nature and characteristics of instruction that are effective in reducing the incidence of early reading difficulties and on how to help teachers become more effective in this regard. It is widely acknowledged that teachers’ professional knowledge is not complete upon certification (Snow, Griffin & Burns, 2005) and, therefore, on-going professional education is likely to be critical to the development of a highly effective teaching force. However, the National Reading Panel (2000) found it difficult to make specific recommendations about PD because of the paucity of research showing that PD changed both teachers’ practices and their students’ achievement. Studies of the effects of PD on classroom instruction are particularly important, because classroom instruction has the potential to affect the largest number of students. Moreover, if changes at the classroom level reduce the number of children who need more intensive interventions, the schools’ capacity to provide subsequent tiers of intervention will be enhanced because fewer students will need to be served.

Thus, the current study was conceived, in part, in response to the need for research on the contribution of PD to teachers’ instruction and students’ reading achievement. The study was also partly motivated by an earlier study (Scanlon et al., 2005; Vellutino, Scanlon, Small, & Fanuele, 2006) which showed that the number of children who experienced early reading difficulties could be substantially reduced through the provision of a rather limited kindergarten intervention program (30 minutes twice per week for 25 weeks) that supplemented the classroom program. That study also demonstrated that children who experienced reading difficulties, despite having the supplemental intervention in kindergarten, were much less likely to demonstrate severe reading difficulties at the end of first grade than were children who did not participate in kindergarten intervention. We reasoned that PD for classroom teachers, based on the intervention approach, could be equally or perhaps more effective in reducing the incidence of early reading difficulties.

Research Purposes

We used a longitudinal study that compared three approaches to reducing the incidence of early reading difficulties: 1) Professional Development Only (PDO), 2) Intervention Only (IO), and 3) Both PD for teachers and Intervention for their students who were at increased risk of experiencing early reading difficulties (PD+I). The PD provided to the classroom teachers was similar to the PD program provided to intervention teachers in the Scanlon et al. (2005) study. The small group intervention provided to the at risk kindergartners in the IO and PD+I conditions was the same as the intervention provided in the Scanlon et al. study. This was, essentially, a Tier 2 intervention.

Outcomes included both measures of student achievement and documentation of the characteristics of kindergarten classroom language arts instruction. Data were gathered as the teachers taught three consecutive cohorts of students in the years before (Baseline Cohort), during (Implementation Cohort) and after (Maintenance Cohort) the various treatments were instituted. Because personnel from the research team were actively involved in guiding and supporting classroom instruction for the Implementation Cohort, the major analyses are focused primarily on contrasts between the Baseline and Maintenance cohorts.

With regard to student achievement, we anticipated improved outcomes for at risk children in the Maintenance Cohort as compared to the Baseline Cohort in all three treatment conditions. Further, it was predicted that the PDO condition would be at least as effective as direct interventions for children (IO condition) in improving the early literacy skills. However, it was also anticipated that the strongest outcomes would occur in the PD+I condition, since the children would have the benefit of both enhanced classroom instruction and additional small group intervention..

With regard to classroom observations, it was anticipated that, for teachers in the PD and PD+I conditions, comparisons of Baseline versus the Maintenance year data would reveal a shift toward instruction that was aligned with the content of the PD program and more responsive to the needs of individual children. Thus, in comparisons of instruction provided for the two cohorts by the same teachers, it was expected that for the Maintenance Cohort:

more time would be allocated to language arts instruction;

more instruction would be focused on content related to the literacy goals of the PD program;

greater use would be made of literacy materials that allowed students to practice and apply skills and strategies related to the literacy goals; and

greater support would be provided for at risk students through differentiated instructional groupings and greater use of responsive modeling and scaffolding.

Method

Design

This study assessed the effects of three approaches to intervention provided for kindergarten children who were in the at risk range on a measure of early literacy skill: Professional Development Only for classroom teachers (PDO); supplemental, small group Intervention Only (IO); or both PD and supplemental Intervention (PD+I). All approaches utilized the Interactive Strategies Approach (ISA) to preventing reading difficulties (described below). Both longitudinal and experimental contrasts were included. To assess longitudinal effects, three consecutive cohorts of kindergartners were followed from the beginning of kindergarten to the beginning of first grade. For the Baseline Cohort, no research treatment occurred. All treatments were initiated with the Implementation Cohort. For the Maintenance Cohort, the PD activities for the teachers were discontinued however the direct interventions for children who were at risk continued in the IO and PD+I conditions.

A randomized block design was used to assign schools to the three treatment conditions. Toward the end of the Baseline Cohort’s kindergarten year, schools were assigned to one of the three groups with the groups being matched as closely as possible for SES, risk status for entering kindergarten students, and grade 4 achievement on the New York State English Language Arts assessment. Schools from within the same district were assigned to different groups in order to distribute the effects of curricula.

Participants

Teachers

Schools were eligible to participate in the study if they 1) served a relatively high number of low income students, 2) offered full day kindergarten; and 3) were within 50 miles of our research center in Albany, New York. In schools that met the criteria and expressed an interest in participating, teachers completed consent forms independently and submitted them to the researchers in sealed envelopes. To qualify for the study 80% of the kindergarten teachers needed to agree. Schools were provided with funds for the purchase of language arts materials for each participating classroom after the year of baseline data collection.

Fifteen schools (from ten districts, six urban and four rural) and 43 kindergarten teachers elected to participate in the study. All of the teachers were Caucasian women, a circumstance that is quite typical in the Albany, NY area. Because of the substantial demands of the study and because a fairly high number of schools had half-day kindergarten programs at the outset of the study, it was not possible to limit enrollment to schools that had full day kindergarten. Therefore, two schools that had half-day kindergarten during the Baseline Cohort’s kindergarten year, but full day kindergarten for the subsequent cohorts, were included in the study but excluded from the current report. Another school was excluded because it was closed at the end of the Baseline Cohort’s kindergarten year. The elimination of schools reduced the teacher sample to 38 teachers.

During the three years of data collection, teacher attrition occurred as a result of teachers retiring, taking leave, moving, or taking non-teaching positions. After attrition, the sample consisted of 28 teachers for whom 3 consecutive years of data were available.1 Four schools were included in each condition, with 1–4 teachers per school. The final sample included 9 teachers in IO schools, 10 teachers in PDO schools, and 9 teachers from PD+I schools.

Students

Students taught by the 28 teachers in this study were also participants in the research. Kindergarten students were recruited at the school’s kindergarten registration or through letters sent home with the child. In all but one school, over 90% of parents agreed to involve their children. Only children who were available for assessment at all measurement points are included in this report. Table 1 provides demographic data for each cohort and condition.

Table 1.

Percentages of children in each subgroup in each cohort and condition falling in each condition.

| Intervention Only | Professional Development Only | Professional Development + Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Imp | Main | Base | Imp | Main | Base | Imp | Main | |

| Racial/Ethnic Group | |||||||||

| Asian | 5.5 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| African American | 12.3 | 17.1 | 15.2 | 10.8 | 6.1 | 9.7 | 7.9 | 11.3 | 6.3 |

| Hispanic | 2.5 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 7.0 | 1.4 |

| White | 77.9 | 71.8 | 75.2 | 84.1 | 87.1 | 80.0 | 77.9 | 69.0 | 88.9 |

| Other & Missing | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 6.9 | 11.4 | 11.3 | 2.8 |

| Male | 55.8 | 59.0 | 48.8 | 44.0 | 47.9 | 49.0 | 44.3 | 52.1 | 51.4 |

| Free & Reduced Luncha | 34.4 | 27.5 | 40.0 | 24.8 | 31.9 | 50.3 | 40.7 | 34.5 | 51.4 |

There is a fair amount of missing data (3% to 15%) for each group owing to reluctance on the part of the schools to release data on the children’s free and reduce lunch status.

Note: Base=Baseline, Imp= Implementation, Main=Maintenance

Early Literacy Leaders

Each school nominated one individual to serve as an (Early) Literacy Leader (LL). In schools assigned to the PD conditions, the LLs were expected to provide on-going support to teachers in their school once active engagement in the PD component concluded. In schools in the IO and PD+I conditions, the LLs, in most cases, provided the intervention to one group of kindergartners in the Implementation Cohort. The LLs in the IO condition were expected to provide PD for teachers in their schools once the teachers had finished working with the Maintenance Cohort.

The LLs were all Caucasian women. Many LLs were teachers including three classroom teachers, three reading teachers, and three who taught both special education and reading. The group also included one speech and language pathologist, and three building administrators who held reading certification. All had at least 10 years teaching experience. LLs participated in the same PD as the classroom teachers. They also had ongoing monthly contact with project staff to enhance their professional knowledge.

Measures

The same data collection procedures were used for all three cohorts (Baseline, Implementation, and Maintenance). The children were assessed in the early fall and late spring of kindergarten and at the beginning of grade one.

Student Measures

PALS

The kindergarten version of the Phonological Awareness and Literacy Screening Battery (PALS - K, Invernizzi, Meir, Swank & Juel, 1999–2000) was administered to kindergartners at the beginning and end of the school year. This is a standardized measure that provides benchmarks for the identification of children who are at risk for literacy learning difficulties. The Rhyme Awareness, Beginning Sound Awareness, Alphabet Knowledge, Letter-Sound Knowledge and Spelling components were administered. The maximum score summing these subtests is 92 points. Risk status at each measurement point was based on the published benchmark (28 in the Fall and 74 in the Spring). Internal consistency reliability coefficients based on the subtests range from .79 to .85 for various subsamples (Invernizzi, Meier, Swank, & Juel, 2000).

The PALS 1–3 (Invernizzi & Meir, 2000–2001) was administered at the beginning of first grade. The outcome measure utilized for this study was the Entry Level Summed score which is the sum of the Spelling and Word Recognition components. The maximum possible score for this index is 77. The test manual reports reliability and validity indices within acceptable ranges (.73–.90).

Basic Reading Skills Cluster

At the beginning of grade 1, all students were administered subtests from the Woodcock-Johnson III Testsof Achievement (WJIII, Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001). Scores from the Letter-Word Identification and Word Attack subtests were used to derive a Basic Reading Skills Cluster (BSC) score. For four to seven year olds, the age-corrected test-retest reliability coefficient for a one year interval is .92. For the current sample, the beginning of first grade PALS Summed Score correlated .88 with the BSC.

Classroom Observations

CLASSIC

The Classroom Language Arts Systematic Sampling and Instructional Coding (CLASSIC) system was used to gather information on instructional characteristics (Scanlon, Gelzheiser, Fanuele, Sweeney, & Newcomer, 2003). The CLASSIC is a modified time-sampling teacher observation system. The observer records both a running narrative of the instructional events involving the teacher and every 90 seconds records verbatim a “slice” or instructional event that is coded for seven features of instruction. The combination of the running narrative and the verbatim record provided sufficient context to allow the observer to reflect on how to best code an event, and also allowed another coder to review coding decisions.

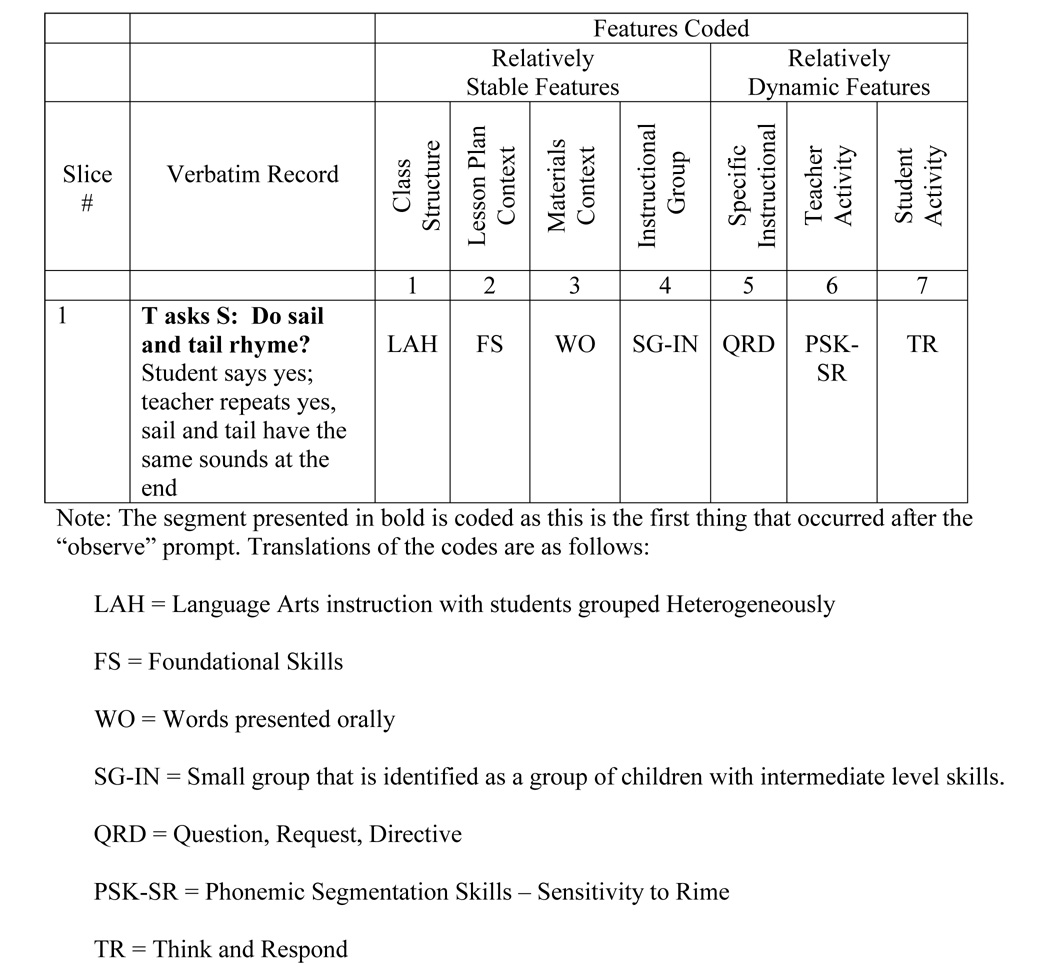

Six of the seven coded features focus on the teacher; the seventh feature captures the students’ response. Of the seven features, four tended to remain stable for periods of time and three tended to change frequently as the teacher interacted with students. (See Figure 1 for an example of a coded slice.) Detailed information about the CLASSIC observation system can be obtained from the first author.

Figure 1.

Sample of coded slice taken in the context of a small group lesson focused on the development of phonemic awareness. The teacher identified the group as her “middle” group prior to the observation.

Relatively Stable Features

The codes used for the Class Structure feature captured whether all children were engaged in a single activity or whether multiple activities were occurring simultaneously. For the Lesson Plan Context feature, codes allowed the observer to document major instructional blocks of the sort typically recorded in lesson plans (e.g., read aloud, text reading, skills, calendar time, writing, non-language arts activities). Codes for Materials Context identified the materials the teacher was using during instruction (e.g., trade book, letters, pictures, math materials). Instructional Group codes identified the group with whom the teacher was interacting, allowing for an estimate of the time that the teacher provided instruction in whole class versus small group settings and also capturing whether the small groups were heterogeneous or based on instructional needs.

Relatively Dynamic Features

To capture the dynamic nature of instruction, we coded three characteristics of instruction. Codes for the Specific Instructional Focus indexed what students were expected to focus on, that is, the many objectives, sub-objectives, or tasks related to reading, writing, speaking, and listening. There were codes to indicate whether instruction was focused on such things as letter names, letter sounds, phonemic analysis, reading text, listening to text, comprehension of text read or heard, etc. Teacher Activity codes were used to indicate the instructional activity that the teacher used, for example, activity specifically focused on text (e.g., transcribing students’ dictation), activity to promote acquisition of information or skills (e.g., scaffolding), or activity that did not involve instruction (e.g., managing behaviors). Student Activity codes were used to indicate what students were doing during the coded event (e.g., oral reading, shared reading, thinking about and/or providing a response, listening, art).

Variables Used in Analysis

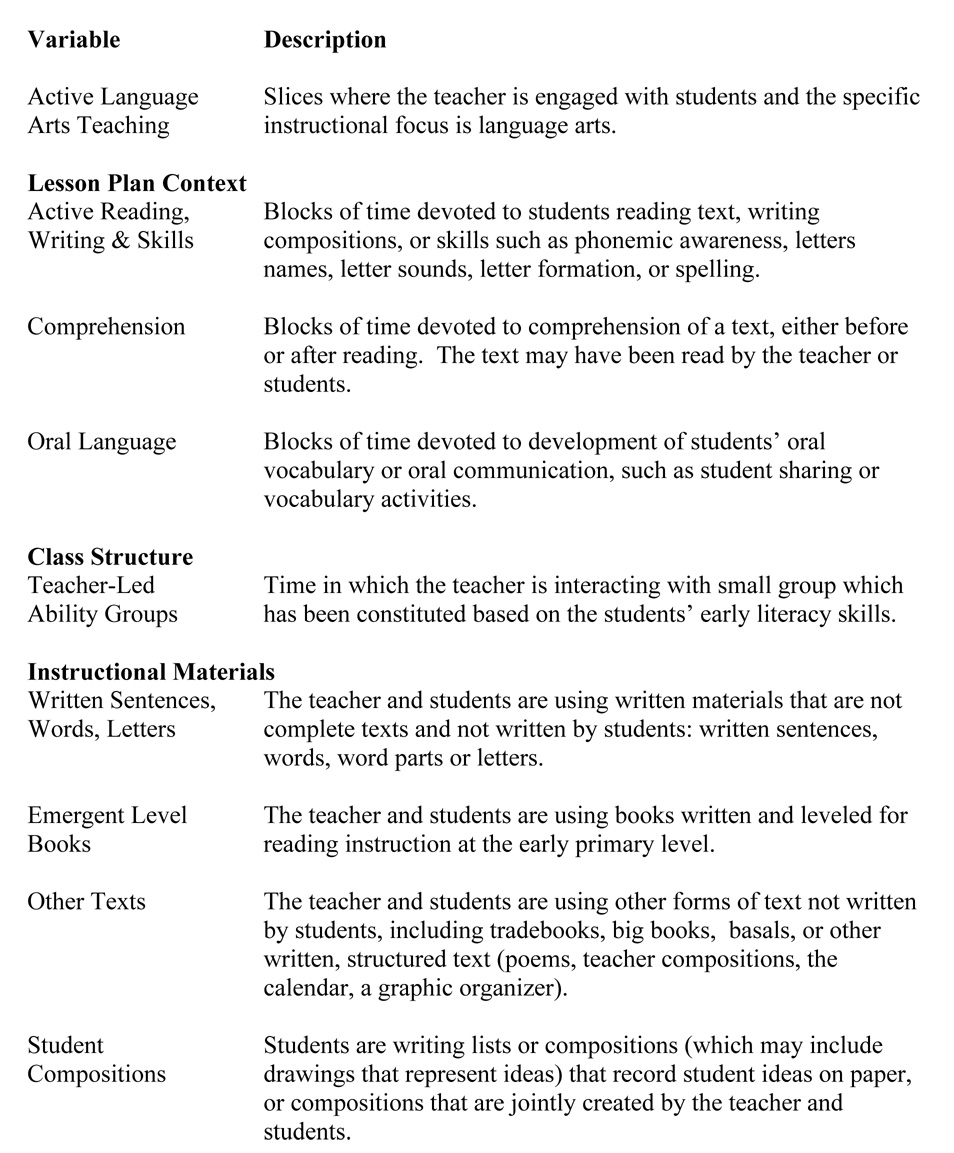

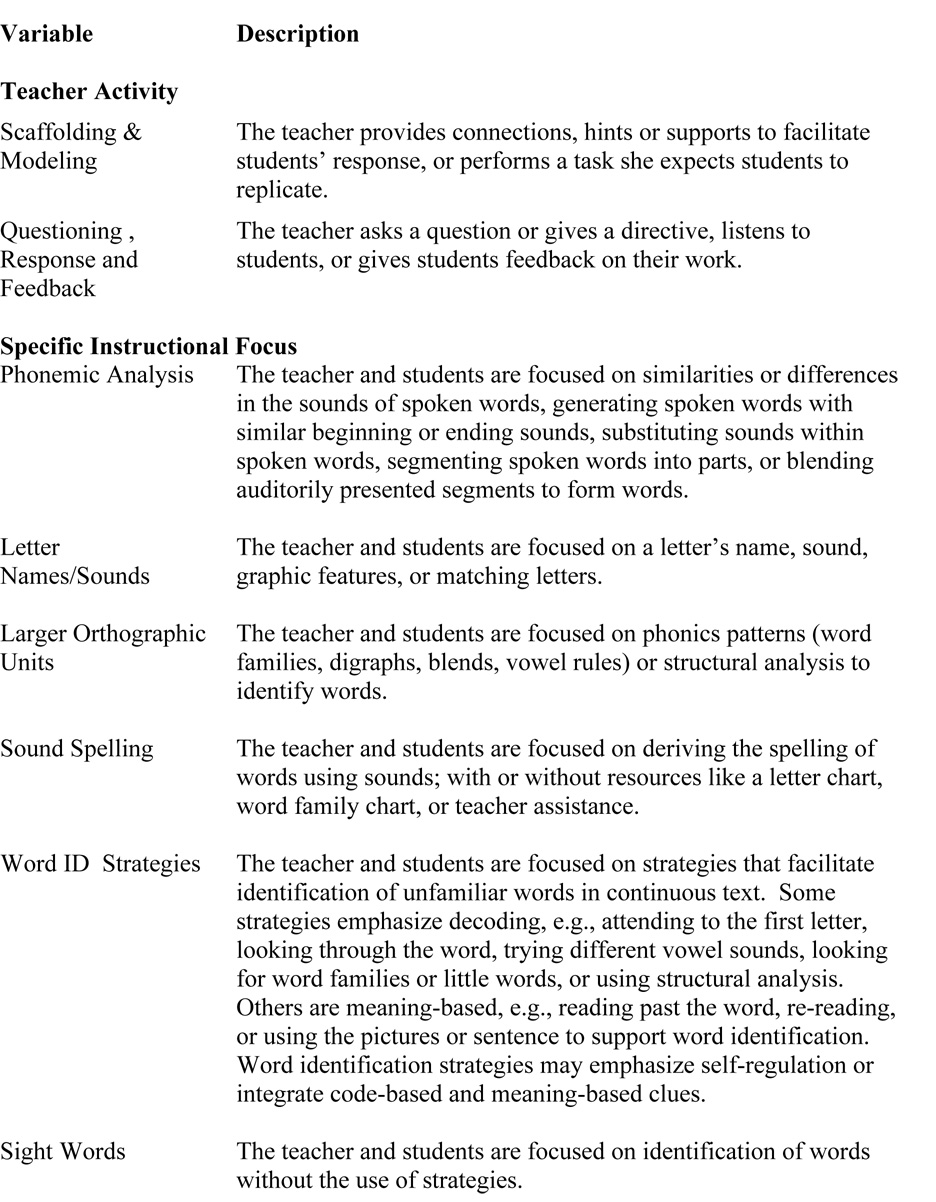

For purposes of analysis, we consolidated codes to make composite variables that aligned with the research purposes. These composite variables were based primarily on the literacy goals of the Interactive Strategies Approach and the PD program. For example, the PD stressed active engagement of students; we captured student engagement in the coding system with codes such as Every Student Response and Thinking and Responding. Codes that occurred infrequently were often collapsed with conceptually related codes to form meaningful and interpretable instructional constructs.2 For example, the Specific Instructional Focus feature includes 13 phonemic analysis codes which were combined to form one variable. Each of the variables used in this analysis is defined in Figure 2a (relatively stable features) and Figure 2b (relatively dynamic features).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Derived variables for the relatively stable features used in the analysis of observation data.

Figure 2b. Derived variables for the relatively dynamic features used in the analysis of observation data.

Reliability

Guided by a coding manual, observers were trained through coding written examples and videos. Once an observer demonstrated acceptable reliability in coding the videos, she/he accompanied the “standard” observer on live classroom observations and coded using the same time sample. To qualify to do independent observations, new observers needed to demonstrate that they had attained the requisite reliability level in two consecutive observations. Thereafter, reliability checks were conducted every 6 to 8 weeks. Reliability was calculated for each instructional feature as well as overall. The criterion set for acceptable reliability was 85% agreement for each feature and 90% agreement across the 7 features coded. Average feature reliabilities ranged from 99% for Classroom Structure to 93% for Specific Instructional Focus.

Procedures

Data Collection

Similar procedures were followed for data collection during the Baseline, Implementation, and Maintenance years of the study. All participating children were assessed within the first 3–4 weeks of kindergarten and again during the last month of kindergarten using the PALS-K. Students who were not lost through attrition were assessed again at the beginning of first grade using both the PALS 1–3 and the Woodcock-Johnson-III measures.

Observations of teachers’ language arts instruction were conducted five times per year. Teachers identified a 2-hour (approximate) time period when they conducted language arts instruction. To maximize representativeness, observations were distributed across the school year, days of the week, and observers. During the Implementation year, three of the five observations of teachers in the PD conditions were conducted by a literacy coach who was supporting the teacher’s ISA related PD. Because of the potential for bias, we do not present observation data collected during the course of the Implementation year.

Treatments – Implementation Cohort

Professional Development

Teachers in schools assigned to the PDO or PD+ I conditions participated in a 3 day workshop concerned with the Interactive Strategies Approach (ISA, Scanlon & Sweeney, 2004; Vellutino & Scanlon, 2002) during the summer prior to teaching children in the Implementation Cohort. They were provided with a handbook and access to the ISA PD website, which included additional teaching ideas.

The Interactive Strategies Approach

The ISA is an approach to early literacy instruction that we have been developing and testing for over 15 years (Scanlon & Sweeney, 2004; Scanlon et al 2005; Vellutino & Scanlon, 2002; Vellutino et al, 1996). It is based on the premise that reading is a complex process that involves the orchestration of multiple cognitive processes, types of knowledge, and reading subskills and that most early reading difficulties can be prevented if literacy instruction is comprehensive, responsive to individual student need, and fosters the development of a Self Teaching Mechanism (Share, 1995). In the earlier studies, the ISA was implemented in small group and one-to-one instructional situations by teachers who were members of our research staff. The current study represents our first attempt to implement the ISA at the classroom level.

The ISA is not a “program”. Rather, it is an approach that is designed to be useful in the context of a variety of language arts programs. In order to plan and organize instruction, teachers need the requisite knowledge and skills to identify what the children are ready to learn and to identify which children would be most appropriately grouped for instruction. Thus the PD program focused on developing teachers’ knowledge in order to enable them to more fully understand their students’ needs. It also provided tools, in the form of techniques and activities, which teachers could select, as appropriate, to help their at risk students make the accelerated progress needed in order to meet grade level expectations. Major emphasis was placed on the need to include small group, differentiated instruction.

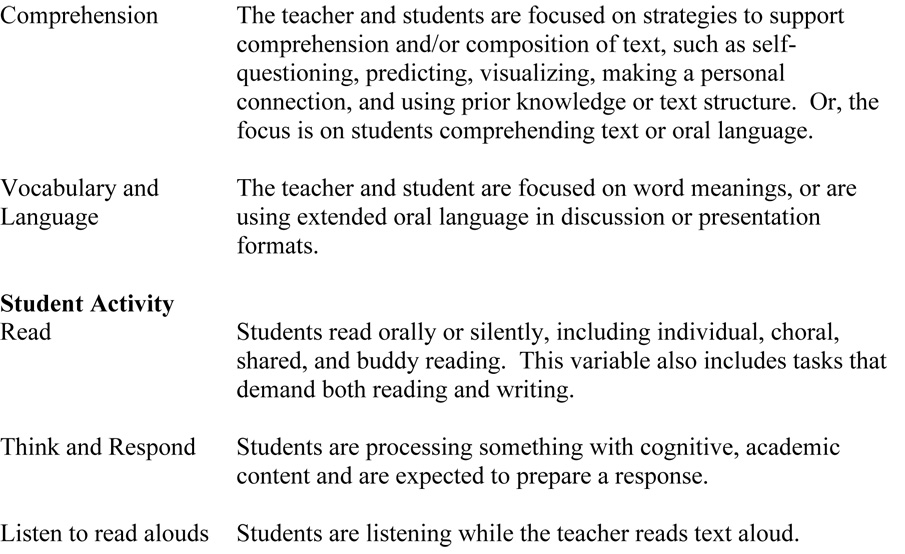

For purposes of the PD program, we organized the approach around ten related instructional goals for emergent readers (see Figure 3). Taken together, the pursuit of these goals was intended to prepare the children to become active and strategic readers who enjoyed and responded to texts read or heard and who applied their knowledge of the alphabetic code in conjunction with contextual cues provided by the text in mutually supportive ways to facilitate the learning of unfamiliar printed words. The goal-oriented structure of the PD program was intended to help teachers focus on these instructional purposes.

Figure 3.

Instructional Goals of ISA at the Kindergarten Level

Coaching

During the Implementation year, each teacher in the PDO and PD+I conditions was supported by an Early Literacy Collaborator (ELC). The two ELCs were experienced teachers who were certified in reading and who had experience as ISA intervention teachers. The ELCs were considered to be collaborators rather than coaches because their primary purpose was to help teachers identify the ways in which the ISA could be incorporated into the curriculum that was in place. Teachers worked individually with their ELC on at least five occasions. The sessions typically involved observation of the teacher’s 2 to 2 ½ hour language arts block followed by 30 to 60 minute reflection session. Suggestions and modeling were also provided by the ELCs. In addition, the ELCs met once a month with all of the kindergarten teachers at a school. These meetings lasted approximately one hour and allowed the opportunity to review the goals of the ISA and to respond to teacher questions and concerns. The school’s Literacy Leader (LL) frequently attended these meetings.

Intervention

Teachers in schools in the IO condition did not participate in the PD program. At-risk kindergartners in IO and PD+I schools were provided with small group instruction (3 students or fewer) by research staff teachers twice a week. The small group instruction used the Interactive Strategy Approach and followed a lesson format that included reading books (read by the children or the teacher), learning about letters and letter sounds, phonemic awareness, and writing. Research staff teachers participated in an ISA workshop similar to that used in the PD conditions. Lesson logs and audio recordings were kept for each intervention session and were used to assess (and encourage) fidelity to the instructional principles of the ISA; however, since the intent of the ISA is that teachers will modify instruction to effectively address the needs of their students, traditional indices of fidelity cannot be applied. The intervention teachers were provided with group (biweekly) and individual (every six weeks) supervision.

Treatments: Maintenance Cohort

At-risk kindergartners in the Maintenance Cohort in schools assigned to the IO or PD+I conditions received ISA instruction in small groups as was provided for the Implementation Cohort. The research project did not provide additional PD for teachers in the PD conditions. However, the LLs were expected to provide support to teachers in these conditions. The amount and type of support provided varied by LLs was not documented and varied across schools.

Results

Below we present a classification analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of the three treatment conditions in reducing the number of children who qualified as at risk at the end of kindergarten. Because analysis of classification accuracy uses arbitrary cutoff scores, we also analyze the performance levels on the measures administered at the beginning and end of kindergarten and at the beginning of first grade. Thereafter, we analyze the effects of the PD program on the classroom instruction. Finally, we consider the instruction provided by teachers in each of the treatment conditions during the year in which they taught the Baseline Cohort, in an effort to explain unanticipated differences in end of kindergarten performance.

Reductions in the proportion of children who qualified as at risk for reading difficulties

Table 2 presents the percentages of children who were classified as at risk at the beginning and end of kindergarten for the various treatment conditions and cohorts. These data indicate that, in general, at kindergarten entry, the schools assigned to the IO and PDO conditions enrolled comparable proportions of children who were at risk for reading difficulties. The schools assigned to the PD+I condition, on the other hand, enrolled students who were somewhat more likely to score in the at risk range of the PALS-K. This general pattern was evident across all three cohorts. However, the proportion of children who scored in the at risk range at the end of kindergarten varied by both condition and cohort. Considering the Baseline Cohort first, it is clear that, in the IO condition, there was no reduction in the percentage of children who qualified as at risk from the beginning to the end of the kindergarten year. However, in the PDO and PD+I conditions, there was a substantial reduction in the percentage qualifying as at risk from the beginning to the end of kindergarten. This finding suggests that the effectiveness of the instruction provided in kindergarten varied considerably by condition before any of the treatments were implemented. These differences will be more fully explored in a later section.

Table 2.

Percentages of children qualifying as at risk for reading difficulties at the beginning and end of kindergarten.

| Percentage at Risk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Beginning of Kindergarten | End of Kindergarten | ||

| Intervention Only (IO) | Baseline | 156 | 50.6 | 52.6 |

| Implementation | 124 | 52.4 | 31.5 | |

| Maintenance | 125 | 53.6 | 27.2 | |

| Professional Development Only (PDO) | Baseline | 154 | 50.6 | 35.1 |

| Implementation | 164 | 47.0 | 19.5 | |

| Maintenance | 147 | 51.7 | 17.0 | |

| Professional Development + Intervention (PD+I) | Baseline | 137 | 59.9 | 24.8 |

| Implementation | 145 | 57.2 | 17.2 | |

| Maintenance | 144 | 61.8 | 17.4 | |

Comparisons of the percentages of children who qualified as at risk across cohorts within each condition provide an indication of the effectiveness of each treatment. At the end of kindergarten, for all conditions, there was a reduction in the percentage of children who qualified as at risk in the Implementation and Maintenance Cohorts relative to the Baseline Cohort.

To evaluate the significance of the patterns described, a three-level HLM model was fit to the data. Specifically, children’s risk status on the PALS-K at the beginning and end of kindergarten were treated as a repeated measure and nested within classrooms and schools, which were both treated as random effects. Treatment condition, cohort, and time of test were treated as fixed effects. This analysis yielded a main effect for time (F (1, 9) = 217.03, p < .0001) which reflects the general trend for fewer children to score in the at risk range at the end of kindergarten than at the beginning, and a main effect for cohort (F (2, 18) = 7.71, p < .01) which reflects the tendency for fewer children in the Implementation and Maintenance Cohorts to qualify as at risk as compared to the Baseline Cohort. The main effect for condition was not significant. There was, however, a significant interaction effect for time by condition (F (2, 9) = 14.95, p < .01), reflecting the fact that, in general, there were larger differences across conditions at the end of kindergarten in the percentages of children qualifying as at risk than there were at the beginning of kindergarten. The final significant effect for this analysis was an interaction between cohort and time of test (F (2, 18) = 10.09, p < .01). This interaction reflects the greater reduction in the number of children who qualified as at risk at the end of kindergarten in the Implementation and Maintenance Cohorts as compared with the Baseline Cohort. Finally, with regard to the analysis of risk status, neither the interaction between condition and time nor the three way interaction between condition, cohort, and time was significant, suggesting that the conditions were not differentially effective in reducing the incidence of risk status at the kindergarten level.

To further explore the impact of the different treatment conditions on the risk status of children in each of the cohorts, we analyzed the stability of the students’ risk status on the PALS-K from the beginning to the end of kindergarten. Children were classified as follows: True Positives are children who qualified as at risk at both the beginning and end of kindergarten, False Positives are children who qualified as at risk at the beginning of kindergarten but not at the end, True Negatives are children who did not qualify as at risk at either the beginning or end of kindergarten and False Negatives are children who did not qualify as at risk at the beginning of kindergarten but did qualify as at risk at the end of kindergarten. We also explored the sensitivity and the specificity of identifying children who were at risk at the beginning of kindergarten and who remained at risk at the end of kindergarten. These data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Indices of classification accuracy for each cohort within each treatment condition.

| TP | FP | TN | FN | Sensitivitya | Specificity b | Overall Accuracy Rate c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO Baseline | 40.4 | 10.3 | 37.2 | 12.2 | 76.8 | 78.3 | 77.6 |

| IO Implementation | 23.4 | 29.0 | 39.5 | 8.1 | 74.3 | 57.7 | 62.9 |

| IO Maintenance | 22.4 | 31.2 | 41.6 | 4.8 | 82.4 | 57.1 | 64.0 |

| PDO Baseline | 27.3 | 22.1 | 42.9 | 7.8 | 77.8 | 68.1 | 70.2 |

| PDO Implementation | 17.1 | 29.9 | 50.6 | 2.4 | 87.7 | 62.9 | 67.7 |

| PDO Maintenance | 16.3 | 35.4 | 47.6 | .7 | 95.9 | 56.7 | 63.9 |

| PD+I Baseline | 24.1 | 35.8 | 39.4 | 0.8 | 96.8 | 52.4 | 63.5 |

| PD+I Implementation | 16.6 | 40.7 | 42.1 | 0.7 | 96.0 | 50.8 | 58.1 |

| PD+I Maintenance | 16.0 | 45.8 | 36.8 | 1.4 | 92.0 | 44.6 | 52.8 |

Sensitivity = True Positive / True Positives + False Negatives

Specificity = True Negatives / True Negatives + False Positives

Total Accuracy = True Positives + True Negatives

The classification data reveal substantial differences in classification accuracy across conditions and cohorts. For example, for the Baseline groups, it is clear that the highest percentage of accurate classifications overall occurred in the IO condition with approximately equal sensitivity and specificity indices. In contrast, the classification accuracy rate for the PD+I Baseline group is substantially lower but the sensitivity index is much higher than the sensitivity index for the IO group while the specificity index for the PD+I group is much lower than the same index for the IO group. Since the two Baseline groups started kindergarten with similar performance levels on the PALS-K, these data suggest differential effectiveness in language arts instruction with the PD+I Baseline group receiving instruction that was much more effective. Note also that the Baseline group in the PDO condition fell between the IO and PD+I group on all three of these indices and the combined results provide strong evidence of variability in the effectiveness of classroom instruction and of the potential effectiveness of Tier 1 interventions.

Comparisons of classification accuracy within treatment conditions across cohorts reveal a clear trend for overall classification accuracy to be reduced for the Implementation and Maintenance Cohorts as compared to the Baseline Cohort. Further, in all conditions, the sensitivity index improved for the Implementation and Maintenance Cohorts as compared to the Baseline Cohort while the specificity index became worse. In other words, with the changes in instructional experiences that (presumably) occurred as a result of the implementation of the various treatments, it became quite unlikely that a child who did not appear to be at risk at the beginning of kindergarten would perform in the at risk range at the end of kindergarten. Moreover, within each condition, the false positive rate increased substantially for the Implementation and Maintenance Cohorts. In fact, in all three treatment conditions, there were substantially more false positives than true positives in the Maintenance Cohort. These data suggest that, as the quality of instruction improves, assessments designed to identify students who are at risk increase in their sensitivity but decrease in their specificity. These data provide a strong argument for the value of an RTI approach in that risk status was clearly related to instructional experiences. Further, the data also provide strong evidence for the efficacy of PD in enhancing the effectiveness of instruction at Tier 1.

Performance on kindergarten measures of student achievement

Table 4 provides means and standard deviations for PALS-K assessment administered at the beginning and end of kindergarten for the children grouped by PALS-K risk status at kindergarten entry. For the children in the at risk range, the data reveal that, across cohorts and treatment conditions, the children performed at similar levels on the PALS-K pretext. However, the PALS-K posttest data reveal substantial differences by treatment condition even for the Baseline Cohort. In general, consistent with the risk reduction data described above, at the end of kindergarten, students in the IO condition performed below the level of the children in the PDO and PD+I conditions. The combined results suggest that Tier 1 instruction at the kindergarten level can be at least as effective in reducing the number of kindergarten children at risk for early reading difficulties as Tier 2 supplemental intervention.

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations on the Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening (PALS – K) for each treatment group and cohort at the beginning and end of Kindergartena

| At Riskc | Not At Riskc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % At Riskb | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| IO | Baseline | Mean | 16.41 | 58.28 | 48.66 | 79.14 | |

| (n=156) | 50.6 | (SD) | 6.99 | 18.24 | 16.20 | 9.13 | |

| Implementation | Mean | 18.05 | 72.12 | 52.85 | 81.86 | ||

| (n=124) | 52.4 | (SD) | 6.73 | 17.43 | 15.66 | 7.71 | |

| Maintenance | Mean | 16.46 | 73.60 | 53.98 | 82.64 | ||

| (n=125) | 53.6 | (SD) | 6.86 | 12.49 | 15.51 | 9.14 | |

| PDO | Baseline | Mean | 16.33 | 66.17 | 49.13 | 83.09 | |

| (n=154) | 50.6 | (SD) | 7.16 | 18.65 | 15.10 | 8.14 | |

| Implementation | Mean | 17.71 | 74.23 | 52.62 | 85.18 | ||

| (n= 164) | 47.0 | (SD) | 6.74 | 16.80 | 15.71 | 5.33 | |

| Maintenance | Mean | 16.61 | 77.11 | 51.24 | 86.70 | ||

| (n= 147) | 51.7 | (SD) | 6.92 | 14.31 | 15.56 | 4.73 | |

| PD+I | Baseline | Mean | 15.29 | 72.72 | 44.35 | 85.38 | |

| (n=137) | 59.9 | (SD) | 6.82 | 15.33 | 13.10 | 5.10 | |

| Implementation | Mean | 15.88 | 77.71 | 49.44 | 88.24 | ||

| (n=145) | 57.2 | (SD) | 6.94 | 13.59 | 14.67 | 4.40 | |

| Maintenance | Mean | 16.62 | 78.87 | 50.33 | 87.75 | ||

| (n=144) | 61.8 | (SD) | 6.35 | 13.45 | 14.27 | 5.32 | |

Maximum score on the PALS = 92

Percent at risk at kindergarten entry

Students are grouped by risk status at kindergarten entry

The students who did not qualify as at risk at kindergarten entry, scored substantially higher than the at risk children at both the beginning and end of kindergarten. Another general trend evident in Table 4 is that, at the end of kindergarten, the children in all of the Implementation and Maintenance Cohorts consistently performed at higher levels on the PALS-K than did children in the Baseline Cohort. This pattern suggests that all three treatment conditions were effective in improving outcomes for children in both the at risk and the not at risk groups. It should be noted that smaller cohort differences emerged for the children who were not at risk. As the PALS-K has a maximum score of 92, this may be attributable to ceiling effects.

To test the effects of the various factors that might influence performance, a three-level HLM model was fit to the data. Student performances on the PALS-K total score at the beginning and end of kindergarten were treated as a repeated measure and nested within classroom and school, which were treated as random effects. Fixed effects in the model were treatment condition, cohort, subjects’ risk status at kindergarten entry, and time of test for the PALS. This analysis yielded a main effect for cohort (F (2, 18) = 41.00, p < .0001), risk status (F (1, 9) = 2299.60, p < .0001), and time of test ( F (1, 9) = 9181.57, p < .00001) but no main effect for treatment condition (F (2, 9) = 1.51, p = .27). There was also a significant Time by Condition interaction (F (2, 9) = 33.39, p < .0001) which reflects that fact that, in the Fall of kindergarten, all performance levels in each of the conditions were comparable but, at the end of kindergarten, the performance levels were substantially different with the PD+I condition performing better than the PDO condition which performed better than the IO condition.

Analysis of beginning and end of year PALS-K performances also yielded significant three-way interaction for cohort by risk status by time of test (F (2, 28) = 14.57, p < .001). To follow-up the significant three-way interaction, we constructed a series of post-hoc interaction contrasts to compare the means on the PALS-K total score within treatment group across cohorts, risk status, and time of test. We also evaluated the magnitude of change separately for at risk and not at risk groups. For the at risk groups, the change from the beginning to the end of kindergarten for the Implementation Cohort was significantly greater than the change for the Baseline Cohort (t (18) = −4.98, p < .0001). Change in the Maintenance Cohort was also significantly greater than change in the Baseline Cohort among the at risk children (t (18) = −6.62, p < .0001). Similar contrasts comparing change from the beginning to the end of kindergarten for the children who were not at risk did not yield statistically significant differences between cohorts. However, these outcomes may have been due to ceiling effects (note that 92 is the PALS-K’s maximum score and that standard deviations are reduced in Table 4). Taken together, these analyses make it clear that all three approaches to enhancing the development of early literacy skills had a positive impact on student performance, especially for students in the at risk group.

Performance on beginning of first grade measures of student achievement

To evaluate the stability of the effects observed at the end of kindergarten, parallel analyses were conducted on the PALS 1–3 and for the Basic Skills Cluster administered at the beginning of first grade (Table 5).3

Table 5.

Means and standard deviations for each treatment group and cohort on measures administered at the beginning of first grade.

| PALS 1–3a | Grade 1 | WJBSCb | Grade 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At Risk | Not At Risk | At Risk | Not At Risk | |||

| IO | Baseline | Mean | 27.66 | 50.03 | 93.68 | 111.28 |

| (n=129) | (SD) | 13.78 | 16.32 | 13.09 | 15.09 | |

| Implementation | Mean | 37.98 | 52.61 | 100.73 | 113.88 | |

| (n=107) | (SD) | 15.34 | 14.38 | 11.46 | 15.53 | |

| Maintenance | Mean | 38.45 | 57.04 | 99.54 | 116.24 | |

| (n=110) | (SD) | 15.16 | 14.09 | 11.01 | 15.34 | |

| PDO | Baseline | Mean | 38.12 | 57.01 | 100.03 | 113.70 |

| (n=131) | (SD) | 16.60 | 16.18 | 11.99 | 13.80 | |

| Implementation | Mean | 43.25 | 57.62 | 102.82 | 116.29 | |

| (n=151) | (SD) | 15.01 | 13.74 | 10.56 | 13.57 | |

| Maintenance | Mean | 45.69 | 60.57 | 104.79 | 117.71 | |

| (n=129) | (SD) | 16.15 | 14.13 | 10.87 | 13.38 | |

| PD+I | Baseline | Mean | 43.66 | 59.78 | 101.95 | 115.56 |

| (n=109) | (SD) | 15.47 | 13.72 | 11.96 | 12.72 | |

| Implementation | Mean | 47.97 | 65.74 | 105.17 | 120.09 | |

| (n=119) | (SD) | 16.12 | 9.64 | 13.85 | 10.57 | |

| Maintenance | Mean | 48.64 | 63.16 | 104.99 | 118.21 | |

| (n= 120) | (SD) | 16.00 | 12.56 | 13.03 | 12.01 |

Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening, first through third grade version

Woodcock-Johnson Basic Skills Cluster

The three-level HLM analysis of the PALS 1–3 at the beginning of first grade revealed a main effect for cohort, (F(2,18)= 18.05, p < .0001), initial risk status (F (1,9) = 386.30, p < .0001), and condition (F (2, 9) = 4.60, p = .042). None of the interaction effects were significant. Contrasts for the effect of condition indicated that the children in the PD+I condition performed significantly better than those in the IO condition (t (9) = − 3.03, p = .014). The performance level for the PDO condition was intermediate between the IO and the PD+I conditions and did not differ significantly from either condition. With regard to the cohort effect, the Baseline Cohort performed substantially below the Implementation (t (18) = −4.50, p < .001) and Maintenance Cohorts (t (18) = −5.69, p < .001) while the Implementation and Maintenance Cohorts did not differ significantly.

Analyses of the BSC revealed a similar pattern with significant main effects for cohort (F (2, 18) = 11.44, p < .001) and initial risk status (F (1, 9) = 349.61, p < .001) but only a marginal effect for condition (F (2, 9) = 2.71, p = .119). Follow-up tests of the cohort effect demonstrated statistically significant mean differences between the Baseline Cohort and Implementation Cohort, t(18)=3.97, p=.0009, and between the Baseline Cohort and the Maintenance Cohort, t(18)=4.28, p=.0004, with the Baseline Cohort performing worse than the other two cohorts. The initial risk main effect revealed that students at-risk performed more poorly than students not at risk. There was no evidence that the gap between the two groups narrowed; the difference in performance between the at risk and not at risk groups was essentially the same for the Baseline and Maintenance Cohorts. In the IO condition we expected that such a narrowing would occur since no treatment was provided that would influence the reading skills of not at risk children. It is not a surprise, of course, that PD for classroom teachers provided in the PDO and PD+I conditions would have influenced the performance of both the at risk and the not at risk children.

Teacher Observation Data

From the CLASSIC, we derived variables that captured specific teacher activities and practices that were the focus of the PD program and that early literacy research suggests should be related to success in early literacy development. The observation data were then analyzed to determine whether and how the kindergarten teachers who participated in the PD program (PDO and PD+I conditions) changed their instruction from the Baseline to the Maintenance year. We also conducted an exploratory analysis using CLASSIC data collected when the teachers taught the Baseline Cohort in an effort to explain the substantial end of kindergarten performance differences across the three treatment conditions.

The observation data that were ultimately analyzed included only those periods of time that were coded as Language Arts time. Further, because teachers’ schedules varied we included only the blocks of time that were devoted to language arts instruction and, within those blocks, only those slices in which the teacher was actively engaged in instruction.4

The effects of PD on instruction

As teachers from the PDO and PD+I conditions participated in the same PD program and since the sample of teachers for whom we had three consecutive years of data was limited, we opted to combine the PDO and PD+I groups to increase sample size and power. Before the decision was made, we examined the teaching activities of the two groups, and found few differences. To evaluate the effects of the PD program on instruction, we compared observation data for the Baseline Cohort and the Maintenance Cohort. Data gathered while the teachers taught the Implementation Cohort are presented but not specifically analyzed because they were collected while the teachers were being actively coached and because the lasting effects of PD were of more interest than the potentially temporary effects that were observed during the period of active PD.

Data included calculation of effect sizes (Glass’ d) comparing observations during Baseline and Maintenance years. In addition, HLM analyses, with teachers nested within schools, were conducted to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the Baseline and Maintenance years. Table 6a and 6b present the means and standard deviations across the five observations for the number of slices that were coded as Active Language Arts instruction and for the number of times each (derived) observation code5 was assigned. It is important to note that the means are computed on raw counts. Note that for the relatively stable features (Table 6a) the amount of time allocated to particular instructional activities can be estimated by multiplying the number of times a particular code was assigned by 1.5 minutes (representing the time interval for each observational slice). Such time estimates are not possible for the relatively dynamic features of instruction (Table 6b).

Table 6.

| a. Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes for the relatively stable features of instruction coded (PDO and PD + I teachers combined. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Mean (SD) |

Implementation Mean (SD) |

Maintenance Mean (SD) |

Baseline Versus Maintenance Effect Size | Baseline Versus Maintenance p value | ||

| Average Number of Slices per Observation | 85.2 | 101.6 | 99.7 | .65 | <.001 | |

| (19.3) | (24.5) | (22.5) | ||||

| Active Language Arts Teaching | 41.8 | 52.2 | 51.5 | 0.75 | <.0001 | |

| (13.0) | (18.1) | (13.7) | ||||

| Lesson Plan Context | ||||||

| Active Reading, Writing & Skills | 23.8 | 28.9 | 32.5 | 0.83 | <.0001 | |

| (10.5) | (10.8) | (11.9) | ||||

| Comprehension | 3.1 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 0.05 | Ns | |

| (3.0) | (4.2) | (3.1) | ||||

| Oral Language | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.4 | −0.21 | Ns | |

| (1.4) | (2.8) | (1.4) | ||||

| Class Structure | ||||||

| Teacher-Led Ability Groups | 8.1 | 12.0 | 15.7 | 0.96 | <.0001 | |

| (7.9) | (10.9) | (9.7) | ||||

| Instructional Materials | ||||||

| Written Sentences, Words, Letters | 10.4 | 9.2 | 15.1 | 0.68 | .001 | |

| (7.0) | (5.2) | (9.6) | ||||

| Emergent Level Books | 5.1 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 0.45 | .03 | |

| (5.7) | (7.4) | (7.8) | ||||

| Other Texts | 11.8 | 15.3 | 13.7 | 0.41 | Ns | |

| (4.5) | (8.7) | (6.7) | ||||

| Student Compositions | 9.0 | 11.1 | 8.3 | −0.15 | Ns | |

| (4.5) | (6.4) | (5.8) | ||||

| b. Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes for the relatively dynamic features of instruction coded (PDO and PD + I teachers combined. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Mean (SD) |

Implementation Mean (SD) |

Maintenance Mean (SD) |

Baseline Versus Maintenance Effect Size | Baseline Versus Maintenance p value | |

| Teacher Activity | |||||

| Scaffolding & Modeling | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.5 | −0.09 | Ns |

| (2.3) | (1.9) | (2.2) | |||

| Question, Response, Feedback | 24.6 | 32.2 | 31.1 | 0.75 | .0003 |

| (8.7) | (12.1) | (8.4) | |||

| Specific Instructional Focus | |||||

| Phonemic Analysis | 1.4 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 0.83 | .004 |

| (1.0) | (2.7) | (2.0) | |||

| Letter Names & Sounds | 6.1 | 5.3 | 9.7 | 0.83 | .009 |

| (4.3) | (3.3) | (7.6) | |||

| Larger Orthographic Units | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.26 | Ns |

| (1.1) | (0.9) | 1.3 | |||

| Sound Spelling | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.7 | −0.14 | Ns |

| (1.5) | (2.3) | (1.2) | |||

| Word ID Strategies | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.23 | Ns |

| (0.9) | (0.8) | (0.9) | |||

| Sight Words | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 0.52 | .09 |

| (1.6) | (2.1) | (1.8) | |||

| Comprehension | 6.5 | 9.2 | 6.4 | −0.01 | Ns |

| (3.0) | (5.0) | (3.7) | |||

| Vocabulary and Language | 3.2 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 0.02 | ns |

| (1.6) | (2.9) | (1.8) | |||

| Student Activity | |||||

| Read | 6.0 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 0.59 | .01 |

| (3.9) | (5.8) | (4.8) | |||

| Think and Respond | 13.6 | 16.2 | 16.0 | 0.45 | .01 |

| (5.4) | (6.2) | (4.5) | |||

| Listen to read Alouds | 2.2 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 1.00 | .04 |

| (1.0) | (2.7) | (2.3) | |||

a Codes were assigned to the verbatim record that was recorded at the beginning of each 90 second observational slice. For relatively stable features, such as Class Structure and Lesson Plan Context, multiplying the number of times the code was assigned by 1.5 (one and one half minutes) provides an estimate of the amount of time that particular instructional characteristics were observed.

Using Cohen’s (1988) guidelines for interpreting effect sizes (0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 suggesting small, moderate and large effects, respectively), the data in Table 6a suggest that PD had a significant, moderate effect on the total amount of time that teachers devoted to language arts instruction, and a significant, large effect on the time allocated to having students actively reading, writing, or engaged in skill activities. However, PD did not change the time that teachers’ allocated to comprehension and produced a small decrease in the time explicitly allocated to oral language, effects that were disappointing, since comprehension and oral language development were important features of the PD program.

Following the PD program, teachers demonstrated substantial increases in the time devoted to teacher-led instruction provided to small, ability-based groups. This was consistent with the PD program, which stressed the need to match instruction to the children’s current capabilities. Also, during the maintenance year, we observed significant increases in the amount of time teachers used printed materials highlighted in the PD such as emergent level books, sentences, words, and letters in isolation. There was no change in the time spent using other texts or student compositions as materials.

Data on the more dynamic features of instruction (Table 6b), indicate that following PD, teachers were coded as engaging with students by questioning, listening, and providing feedback significantly more often than in the Baseline year. This change is consistent with the increase in time devoted to small group instruction. Surprisingly, PD did not yield an observable change in the use of modeling and scaffolding, although these were stressed in the PD.

With regard to specific instructional focus, there were large, significant effects on the number of times that teachers were coded as focusing on phonemic analysis and on letter names, sounds, and graphic features. However, it is noteworthy that phonemic analysis was the focus of instruction only infrequently during our observations. PD also resulted in a moderate increase in the number of times teachers were coded as focusing on developing sight word knowledge; this effect approached significance. Although also a focus of PD, only small, non-significant effects were observed on teachers’ tendency to focus instruction on word identification strategies and on larger orthographic units such as word families, or on the use of instruction focused on sound spelling, comprehension, or vocabulary and oral language.

With regard to student responses during instruction, Maintenance Cohort children were coded as being engaged in listening to read alouds, in reading, and in thinking and responding significantly more often than Baseline Cohort children. All of these effects were consistent with the PD and statistically significant.

In general, the effects of the PD program seem to have had a positive and lasting effect on the kindergarten instruction. During the Maintenance year, as compared with the Baseline year, teachers were observed to spend more time on active language arts instruction, to focus more on the differential needs of the children in their classes, and to focus more on the development of the foundational skills that tend to be associated with early reading difficulties. Following involvement in the PD program, teachers were also observed to more frequently engage the children in reading and in actively thinking and responding.

Comparison across conditions for the Baseline Cohort

At noted previously, there were unanticipated differences across the three conditions for the Baseline Cohort in end of year performance levels on the PALS-K. In an effort to explain these differences, we compared the CLASSIC data for the teachers in the three conditions during the year in which they taught the Baseline Cohort. Tables 7a and 7b provide these data. Note that the effect sizes compare the PD+I condition with the IO condition since these are the two conditions that tended to yield the largest differences in student performance for the Baseline Cohort. The data for the PDO condition are presented for purposes of comparison. Because the number of teachers in each condition is quite small, few of the comparisons are statistically significant and caution must be used in interpreting these contrasts. However, several of the effect sizes are substantial and thus may help to inform our understanding of what constitutes effective instruction.

Table 7.

| a. Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes for CLASSIC codes for relatively stable features of instruction used in observation of teachers in three conditions during the Baseline year.a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO (n = 9) | PDO (n = 10) | PD + I (n = 9) | IO vs. PD+I Effect Size | p value | ||

| Mean slices per observation | Mean | 96.4 | 85.8 | 84.5 | −.60 | ns |

| SD | (18.9) | (19.1) | (20.8) | |||

| Active Language Arts Teaching | Mean | 40.1 | 40.8 | 42.9 | 0.24 | ns |

| SD | (8.2) | (11.3) | (15.3) | |||

| Lesson Plan Context | ||||||

| Active Reading, Writing & Skills | Mean | 17.7 | 23.6 | 24.1 | 0.78 | ns |

| SD | (5.2) | (10.4) | (11.2) | |||

| Comprehension | Mean | 1.7 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 0.77 | ns |

| SD | (1.4) | (2.2) | (3.7) | |||

| Oral Language | Mean | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.4 | −0.24 | ns |

| SD | (2.3) | (1.7) | (1.1) | |||

| Class Structure | ||||||

| Teacher-Led Ability Groups | Mean | 1.9 | 6.6 | 9.8 | 1.12 | <.001 |

| SD | (4.3) | (5.8) | (9.8) | |||

| Instructional Materials | ||||||

| Written Sentences, Words, Letters | Mean | 6.6 | 10.9 | 9.8 | 0.60 | ns |

| SD | (4.7) | (8.1) | (6.0) | |||

| Emergent Level Books | Mean | 1.9 | 4.1 | 6.1 | 0.81 | ns |

| SD | (2.6) | (2.9) | (7.9) | |||

| Other Texts | Mean | 14.9 | 11.2 | 12.6 | −0.54 | ns |

| SD | (3.9) | (4.6) | (4.5) | |||

| Student Compositions | Mean | 7.9 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 0.18 | ns |

| SD | (3.0) | (4.3) | (4.9) | |||

| b. Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes for CLASSIC codes for relatively dynamic features of instruction used in observation of teachers in three conditions during the Baseline year.a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO (n = 9) | PDO (n = 10) | PD + I (n = 9) | IO vs. PD+I Effect Size | IO vs. PD+I p value | ||

| Teacher Activity | ||||||

| Scaffolding & Modeling | Mean | 3.5 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 0.66 | ns |

| SD | (1.1) | (2.2) | (2.6) | |||

| Questioning and Explanation | Mean | 20.1 | 24.0 | 25.3 | 0.58 | ns |

| SD | (8.8) | (8.6) | (9.2) | |||

| Specific Instructional Focus | ||||||

| Phonemic Analysis | Mean | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0.59 | ns |

| SD | (0.7) | (0.7) | (2.7) | |||

| Letter Names/Sounds | Mean | 5.5 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 0.09 | ns |

| SD | (2.8) | (4.6) | (4.2) | |||

| Larger Orthographic Units | Mean | 0.3 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.22 | ns |

| SD | (0.4) | (1.4) | (0.8) | |||

| Sound Spelling | Mean | 0.8 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 0.77 | ns |

| SD | (0.7) | (1.9) | (0.8) | |||

| Word ID Strategies | Mean | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.19 | .03 |

| SD | (0.1) | (0.4) | (1.3) | |||

| Sight Words | Mean | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 0.06 | ns |

| SD | (2.2) | (1.9) | (1.2) | |||

| Comprehension | Mean | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 0.12 | ns |

| SD | (3.1) | (2.3) | (3.8) | |||

| Vocabulary and Language | Mean | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.0 | −0.30 | ns |

| SD | (1.5) | (1.6) | (1.6) | |||

| Student Activity | ||||||

| Read | Mean | 6.1 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 0.12 | ns |

| SD | (3.3) | (2.4) | (5.2) | |||

| Think and Respond | Mean | 9.9 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 0.75 | ns |

| SD | (4.7) | (5.2) | (5.9) | |||

| Every Student Response | Mean | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | NA | ns |

| SD | (0) | 0.2 | 0.0 | |||

| Listen to read alouds | Mean | 3.4 | 2.5 | 1.9 | −1.03 | ns |

| SD | (1.8) | 1.0 | 1.2 | |||

Codes were assigned to the verbatim record that was recorded at the beginning of each 90 second observational slice.

Table 7a reveals that, while there were more observational slices for the teachers in the IO condition compared to the teachers in the other two conditions, the total time allocated to language arts instruction was similar across conditions. The three groups did differ (albeit not significantly) in time allocated to active reading, writing, and skills instruction with the teachers in the PD+I condition devoting nearly 50% more time to this topic than did the teachers in the IO condition. Differences across conditions were striking with regard to teachers attending to understanding and responding to students needs. PD+I teachers spent approximately five times more time in working with small ability-based groups than did the IO teachers. PD+I teachers made substantially greater use of emergent level books and other printed materials that would provide the children with the opportunity to attend to and analyze written text. Teachers in the IO condition made greater use of “other texts” which were typically texts that were read aloud to the children.

PD+I teachers were observed to provide more scaffolding and modeling and to engage in questioning and explanation more often (Table 7b). With the Baseline Cohort, classroom teachers in the PD+I condition focused more often on phonemic analysis, teaching about larger orthographic units, sound spelling, and word identification strategies, that is, topics that would enable the children to effectively use the alphabetic code. However, it is important to note that these foci were coded infrequently. It is also important to note similarities among the PD+I and IO teachers in most frequent topics for instruction: comprehension, letter names and sounds, and vocabulary and oral language.

With regard to what the students were engaged in during language arts instruction, the data in Table 7b reveal that children in the PD+I condition were more often coded as being engaged in thinking and responding than children in the IO condition. On the other hand, children in the IO condition were more often coded as listening to read alouds than the children in the PD+I condition. Children in both conditions were coded as being engaged in reading about equally often.

Taken together, at Baseline, the observation data suggest that the teachers in the PD+I condition differed from the teachers in the IO condition in ways that allowed their students to actively learn early literacy skills. The most striking difference between groups was in the use of small ability-based groupings. In the context of RTI models, teachers are frequently encouraged to attend to the varying instructional needs of the children in their classroom with particular attention to the needs of the children who are not meeting grade level expectations. This recommendation is consistent with the finding that teachers who were most successful in improving the outcomes for their at risk students devoted more time to working with small ability-based groups.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the reading growth of at risk kindergarten children in response to intervention under one of three conditions: professional development for classroom teachers only (PDO), supplemental small group intervention only (IO), or the two treatments combined (PD+I). The Interactive Strategies Approach to reading instruction was used in all three conditions. As previous intervention research had demonstrated that both supplemental small group and one-to-one intervention was effective in reducing the incidence of early reading difficulties (Scanlon et al, 2005; Vellutino et al., 1996), a major question addressed in the current study was whether classroom teachers would also be able to reduce the incidence of early reading difficulties after participating in a PD program designed to improve early literacy instruction. This is an important question given that RTI models view classroom instruction as the first tier of intervention for at risk children.

The findings suggest that all three intervention conditions (IO, PDO, and PD+I) were effective in helping to substantially reduce the incidence of early reading difficulties. Comparisons of performance levels in the Baseline and Maintenance Cohorts in each condition showed that the number of children who qualified as at risk from the beginning to the end of kindergarten was reduced and that the performance levels of at risk children were substantially increased at the end of kindergarten and beginning of first grade. Moreover, the classification analyses suggested that the instructional modifications provided in all conditions were an important determinant of classification accuracy. In general, as instruction became more effective, assessment-based classification accuracy declined. With improvements in instruction, more children made more progress that resulted in both an increase in the incidence of false positives and a decrease in the incidence of false negatives. To an extent, the inclusion of growth parameters of the types typically used in RTI classification studies (Compton, Fuchs, Fuchs, & Bryant, 2006; Vellutino, Scanlon, Zhang, & Schatschneider, in press), indexes the quality of instruction - the more effective the instruction, the greater the growth demonstrated by students receiving the instruction.

The design of this study was intended to allow us to evaluate the relative effectiveness of the three treatment conditions compared. However, comparisons within the Baseline Cohort revealed that, although groups assigned to the three conditions were similar at kindergarten entry, there were marked performance differences after kindergarten instruction. That is, there were substantial differences in classroom teacher effectiveness for the three conditions before the experimental treatments were instituted. These pre-existing differences limit our ability to confidently make direct comparisons related to the relative effectiveness of the three intervention conditions. Thus, given the current data, it is not possible to determine which of the three conditions was more or less effective in improving outcomes for students who qualified as at risk. Therefore, in what follows, we discuss the effects of each condition separately.

The PDO condition served as a Tier 1 intervention. The results for this condition demonstrate that when provided with ISA-based PD, classroom teachers reduced by half (35% Baseline to 17% Maintenance) the number of children who qualified as at risk at the end of the year. Further evidence for the effectiveness of the PDO condition is provided by the improved performance levels of the Maintenance Cohort children who entered kindergarten at risk. As a group, they performed at a substantially higher on the end of kindergarten and beginning of first grade assessments than did the Baseline Cohort.

The IO condition could be considered a form of Tier 2 intervention. The Baseline versus Maintenance group differences at the end of kindergarten were larger in this condition than in the other two conditions. However, because the end of kindergarten and beginning of first grade performance levels for the Baseline Cohort in this condition were much lower than for the Baseline Cohorts in the other two conditions, it seems likely that the large differences are at least partially attributable to substantial weaknesses in the instruction offered by classroom teachers in the IO Baseline Cohort.

We had anticipated that the provision of both professional development for classroom teachers and supplemental instruction for at risk students (PD+I) would have a stronger positive impact on early literacy skills for the at risk children than either of the treatments alone. However, the data do not support this hypothesis. Indeed, considering just the end of kindergarten PALS-K scores, it is evident that the smallest Baseline versus Maintenance differences occurred in the PD+I condition while the largest differences occurred in the IO condition (see Table 4). While this finding could be taken as evidence that the PD+I condition was the least effective, it is important to note that the performance level of the Maintenance group for the IO condition equaled the performance level for the Baseline Cohort in the PD+I condition. Thus, before involvement in any of the interventions instituted by the research project, the teachers in the PD+I condition were already highly effective in promoting growth in literacy skills among their students who were at risk. While the implementation of enhancements to the classroom program through PD and the addition of supplemental small group instruction did result both in reductions in the number of children who qualified as at risk and in overall improvement in performance levels among children in the at risk group, it may be that further improvements would have required the implementation of more intensive intervention (Tier 3) for the children who continued to struggle despite high quality interventions at both Tier 1 and Tier 2. It should be recalled that the Tier 2 intervention offered was rather limited (30 minutes of small group instruction twice per week). On the other hand, it is possible that, as suggested by the LLs when presented with these outcomes, the teachers in the PD+I condition may have felt less of a press to address the needs of their at risk students since those children were receiving supplemental instruction outside of the classroom. Nevertheless, overall, it seems safe to infer that PD for classroom teachers (which supports Tier 1 intervention) was at least as effective as supplemental small group remediation (Tier 2 intervention) in reducing the number of kindergartners who continued to be at risk for reading difficulties over the course of the school year.

Were we to make recommendations for implementing a tiered approach to intervention based on the results of the current study, we would argue strongly for beginning with PD for kindergarten classroom teachers. The current study clearly demonstrates that teachers provided with the type of PD utilized in this project can substantially reduce the number of children who are at risk for reading difficulties at the end of kindergarten. In light of the cost effectiveness of improving the quality of classroom instruction versus providing direct, supplemental interventions to children (which requires additional staffing), the argument in favor of PD for classroom teachers as a critical component of early intervention and Tier 1 intervention in particular seems strong.

This argument is buttressed by observed differences in the effectiveness of classroom instruction among teachers in the different treatment conditions. In order to better understand characteristics of kindergarten language arts instruction that were associated with better child outcomes, we conducted periodic observations of instruction. In the current paper we focused on comparisons of instructional characteristics in the year before and the year after teachers participated in a PD program. We also compared the instructional characteristics of teachers who were found to be particularly effective in promoting early literacy skills among their at risk students in the Baseline Cohort (the teachers in the PD+I condition) and those who were found to be substantially less effective (the teachers in the IO condition). With regard to the effects of PD, the analyses revealed that involvement in the program led teachers to devote more time to language arts instruction. However, that additional time was not evenly distributed across all areas of language arts. Rather, the Baseline-Maintenance group comparisons revealed that, following PD, teachers devoted significantly more time to engaging children in reading text, writing, and learning foundational skills, but no more time to comprehension or oral language development. Further, almost all of the additional time devoted to active language arts instruction could be accounted for by increases in the amount of time devoted to teaching small groups of children with the groups being organized by instructional need. Increases were also noted in the amount of time teachers devoted to actively engaging the children, as evidenced by significant increases in the frequency with which teachers used questioning and provided feedback and the children were observed to be reading or thinking and/or providing responses. During the Maintenance year, teachers were observed to focus more often on developing foundational literacy skills such as teaching about letters and their sounds and developing phonemic awareness. However, although we articulated the need to attend to comprehension and oral language development during the PD program, we apparently did not emphasize this enough since changes in these aspects of instruction tended to be small and transitory (i.e., they were apparent during the Implementation year but not during the Maintenance year.)

Comparisons of the two treatment groups that differed in the effectiveness of the classroom teachers during the Baseline year (IO versus PD+I) yielded results that were largely consistent with the findings derived from the analysis of the effects of PD. Thus, for example, comparisons of the more effective group (PD+I) with the comparatively ineffective group (IO) indicated that the more effective group spent significantly more time during language arts instruction working with small ability-based groups. And, while none of the other comparisons yielded statistically significant differences, the directions of several of the differences were consistent with the findings from the PD comparisons.

Before concluding this paper it is important to discuss some of the limitations of the design and procedures utilized. In designing school-based research it is almost always necessary to deviate from the generally preferred randomized control trial design that can be so powerful in allowing researchers to attribute causality to the experimental treatments. In this study we utilized a quasi-experimental design with assignment to conditions being done at the level of the school in order to avoid the multiple objections that would be raised by parents, teachers, and school administrators when children in the same school are treated in distinctly different ways. An additional limitation was the use of the Baseline Cohort as our primary control group for each treatment. While several interpretational problems can arise with the use of historical control groups, given the goal of explicitly studying the effects of PD for teachers on student achievement and the widely documented variability in teacher effectiveness, having each teacher serve as her own control seemed justified. An additional limitation that must be considered is that all of the teachers in this study volunteered to participate. While this is, of course, the only way such a study could be conducted, it has important implications for generalization of the outcomes. Teachers who were willing to participate in a university-based study that involved classroom observations across a three-year period no doubt differ in multiple ways from teachers who declined to participate.

Summary