Abstract

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as key regulators of transcription, often functioning as trans-acting factors akin to prototypical protein transcriptional regulators. Inside cells, ncRNAs are now known to control transcription of single genes as well as entire transcriptional programs in response to developmental and environmental cues. In doing so, they target nearly all levels of the transcription process from regulating chromatin structure through controlling transcript elongation. Moreover, trans-acting ncRNA transcriptional regulators have been found in organisms as diverse as bacteria and humans. With the recent discovery that much of the DNA in genomes is transcribed into ncRNAs with yet unknown function, it is likely that future studies will reveal many more ncRNA regulators of transcription.

Keywords: ncRNA, RNA polymerase, silencing

Introduction

Transcription — the process by which an RNA copy of one strand of DNA is made — is the first step in gene expression, and as such is highly regulated in all organisms. For years it was thought that the machinery that makes RNA and the factors that regulate its synthesis were proteins. More recently, many examples have been discovered in which an RNA functions to control transcription. These RNA transcriptional regulators are among a class referred to as non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) because they do not harbor open reading frames that encode proteins. ncRNAs that regulate transcription have been found in organisms from bacteria to humans. As a group they control transcription by diverse mechanisms and at multiple levels, from regulating the structure of the chromatin from which RNA is transcribed, to controlling the assembly of transcription complexes on DNA, and even influencing the transcription reaction itself.

The enzymes that perform transcription are DNA-dependent-RNA-polymerases. In general, core RNA polymerases, although capable of making RNA from DNA, cannot initiate transcription in a gene-specific fashion, but instead require accessory factors. Minimally the accessory factors localize the polymerase to the start site of transcription and help the polymerase initiate RNA synthesis. The transcription start sites of genes are contained within promoters, which are the regions of DNA that direct gene-specific transcription initiation. In bacteria, core RNA polymerase is aided by a dissociable protein named sigma factor (Mooney et al., 2005). In eukaryotes, there are three multi-subunit nuclear RNA polymerases: RNA polymerase I (Pol I) transcribes most ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and at least one ncRNA; RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcribes messenger RNA (mRNA) and some ncRNAs; and RNA polymerase III (Pol III) transcribes transfer RNA (tRNA), 5S rRNA, and some ncRNAs. Each of these core RNA polymerases requires accessory factors for transcription, including general transcription factors to form preinitiation complexes at promoters, elongation factors for efficient transcription through genes, and termination factors to complete synthesis of the primary mRNA transcript (reviewed in (Geiduschek and Kassavetis, 1995; Thomas and Chiang, 2006)). Transcription of specific genes is controlled by the actions of protein transcription factors — activators and repressors that bind specific DNA sequences in promoters (Kadonaga, 2004).

Transcription in eukaryotes is also controlled by coregulatory proteins — coactivators and corepressors — that do not bind DNA with sequence specificity, but are recruited to genes by activators and repressors, respectively (Thomas and Chiang, 2006). Some coregulators modulate transcription by communicating with the general transcription machinery, and others do so by changing the structure of chromatin, which is the ensemble of DNA and histone proteins that comprises eukaryotic genomes. Chromatin structure can be changed by post-translational modifications that are added to or removed from the histone proteins (Sterner and Berger, 2000; Shilatifard, 2006; Workman, 2006). Some regions of eukaryotic genomes are condensed into a compact structure referred to as heterochromatin that in general is transcriptionally silent, whereas transcriptionally active regions of the genome, referred to as euchromatin, are less condensed (Grewal and Moazed, 2003). All of the protein factors that function in setting levels of transcription are potential targets for regulatory ncRNAs.

Coincident with the recent surge in identification of ncRNAs that function to control transcription is the finding that the vast majority of the DNA in genomes is transcribed into RNA (reviewed in (Carninci and Hayashizaki, 2007; Kapranov et al., 2007b; Pheasant and Mattick, 2007; Vogel and Wagner, 2007)). In complex organisms the majority of genomic DNA encodes neither proteins nor classical functional ncRNAs, such as rRNA or tRNA. Previously, it was thought that the non-coding regions of these genomes, as well as the antisense strands of genes, were not actively transcribed. Now we know that the majority of genomic DNA is transcribed from both strands, and some of the ncRNAs arising from what was previously considered “junk DNA” can function as transcriptional regulators. This raises the questions: Do many of these newly discovered ncRNAs have functions, and if so, do any of them function as transcriptional regulators? We anticipate the answers to both questions will be yes.

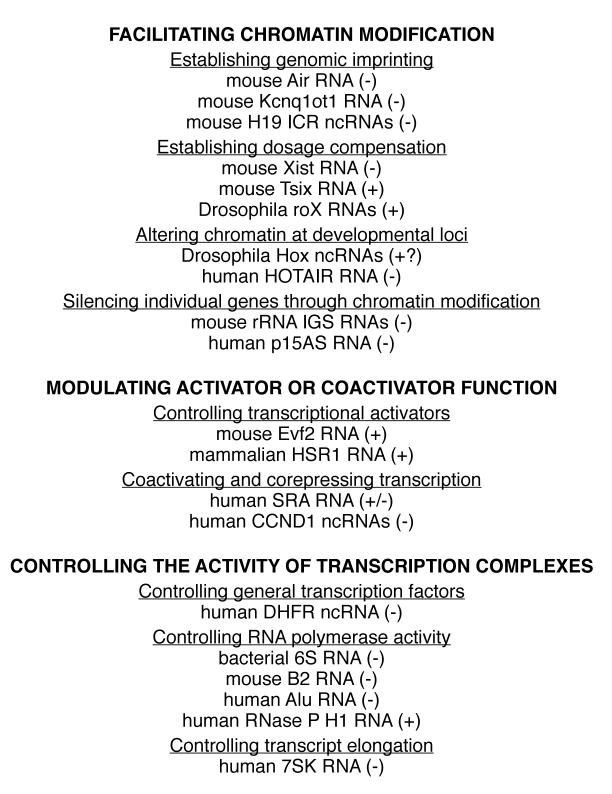

In this review we describe natural ncRNAs that control transcription. All of the ncRNAs we discuss control mRNA transcription in eukaryotes, with the exception of three, which control eukaryotic tRNA or rRNA transcription, or transcription in bacteria. We have grouped the ncRNAs according to their function in regulating the process of transcription, beginning with those that control chromatin structure and ending with an ncRNA that controls transcript elongation (Figure 1). We do not discuss examples in which sequences within a growing RNA transcript regulate its own synthesis (e.g. riboswitches). We also do not discuss siRNA-mediated gene silencing because it has been described in detail in many recent reviews (Wassenegger, 2005; Buhler and Moazed, 2007; Hawkins and Morris, 2008).

Figure 1.

ncRNAs regulate transcription at many levels. Shown are the ncRNAs discussed in this review, grouped according to their function in controlling transcription. For each ncRNA, the organism in which it is best characterized is indicated; however, in some cases the ncRNA is found in related organisms (e.g. mouse and human) and presumed to have a similar function in both. The plus and minus signs in parentheses indicate whether the ncRNA functions to upregulate or downregulate transcription, respectively. The question mark after the plus sign associated with Drosophila Hox ncRNAs indicates that there are conflicting reports on the function of these ncRNAs as transcriptional regulators, as explained in the text.

ncRNAs that facilitate chromatin modification

Multiple ncRNAs have been found to control transcription by mediating changes in the structure of chromatin in eukaryotic cells. Some of the ncRNAs establish large heterochromatin domains, thereby silencing many genes or even entire chromosomes, while others act to alter chromatin in small regions and thereby control single genes or groups of genes. We begin with ncRNAs involved in imprinting and dosage compensation, all of which can be considered monoallelic transcriptional regulators. We then consider ncRNAs that function in pattern formation during development. Finally, we discuss two ncRNAs that silence transcription of specific genes through changes in chromatin structure.

Establishing genomic imprinting

Mammalian cells have two alleles of each autosomal gene — one that is inherited from the mother and one that is inherited from the father. A small subset of genes is known to exhibit monoallelic expression in which a gene is expressed from only the maternal or the paternal allele rather than from both alleles. Restricting expression to a single autosomal allele is called genomic imprinting and it occurs through epigenetic mechanisms (reviewed in (Verona et al., 2003)). The term epigenetic refers to heritable changes in gene expression that are not caused by changes in the sequence of the DNA, for example, through post-translational modifications on histones or methylation on DNA. Approximately 80 genes in mice are known to be imprinted, and they are grouped in clusters containing 3-15 genes (Verona et al., 2003). Typically, at least one gene in an imprinted cluster expresses an ncRNA. A role for the ncRNA in imprinting has been experimentally explored in three imprinted clusters (Pauler et al., 2007). As discussed below, ncRNAs appear to be intimately involved in establishing genomic imprinting; however, the molecular mechanisms by which the ncRNAs mediate silencing at a single allele are not yet understood.

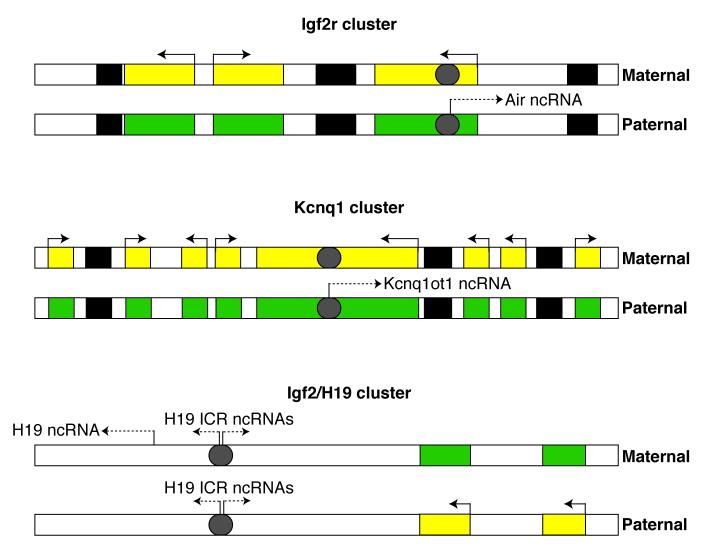

Mouse Air RNA

The Air RNA is transcribed from the imprinted Igf2r locus (Royo and Cavaille, 2008). This locus contains three maternally expressed protein-encoding genes (Igf2r, Slc22a2, and Slc22a3) and the Air non-coding gene, which is paternally expressed (Figure 2). The Air transcript is synthesized by Pol II from an intron in the Igf2r gene, is 108 kb in length, and is polyadenylated but unspliced. Experiments in mice first implicated Air RNA in imprinting because deleting the promoter of the Air gene from the paternal allele resulted in a loss of silencing of the paternal protein-encoding genes; however, deleting it from the maternal allele had no effect (Zwart et al., 2001). In these experiments, deletion of the Air promoter also removed a DNA element known to control imprinting. To more directly investigate the role of Air RNA in silencing the Igf2r, Slc22a2, and Slc22a3 protein-encoding genes, a strong polyadenylation site was inserted downstream of the transcriptional start site for Air RNA (Sleutels et al., 2002). Doing so truncated Air RNA to 4% of its length. Mice containing a paternal truncated Air allele did not exhibit silencing of the neighboring protein-encoding genes. Mice containing a maternal truncated Air allele showed silencing of the Igf2r locus similar to wild type (Sleutels et al., 2002). Therefore Air RNA functions in silencing the flanking mRNA genes on the paternal allele, although the mechanism by which this occurs is unknown.

Figure 2.

Representations of three imprinted mouse clusters (Igf2r, Kcnq1, and Igf2/H19) that exhibit allele-specific expression of protein-encoding and non-coding genes. The maternally and paternally inherited alleles are designated. Yellow bars indicate protein-encoding genes that are expressed, green bars indicate protein-encoding genes that are imprinted and silent, and black bars indicate genes that are not imprinted. The gray circles indicate the imprinting control regions, which are DNA elements that function in controlling monoallelic expression. Expression of the Air, Kcnq1ot1, H19, and H19 ICR ncRNAs are indicated. Adapted from Figure 1 in (Pauler et al., 2007).

Mouse Kcnq1ot1 RNA

The Kcnq1 locus is also imprinted and contains several maternally expressed protein-encoding genes, and a paternally expressed ncRNA named Kcnq1ot1 (Figure 2) (Royo and Cavaille, 2008). The 60 kb Kcnq1ot1 RNA appears to be similar to Air RNA with respect to its silencing function. Deleting a region of the genome containing the Kcnq1ot1 promoter in mice led to a loss of silencing when the deletion was inherited paternally; whereas, inheriting the deleted promoter maternally resulted in normal imprinted expression of all genes at the locus (Fitzpatrick et al., 2002). To determine whether the loss of silencing was due to a loss of the Kcnq1ot1 RNA, as opposed to the complete loss of transcription, a polyadenylation site was inserted to truncate the RNA at 1.5 kb (Mancini-Dinardo et al., 2006). Paternal chromosomes carrying the truncated allele showed expression of eight flanking genes that are typically silent, whereas maternal chromosomes with the truncated allele showed normal imprinting. Therefore, the paternally expressed Kcnq1ot1 RNA silences surrounding mRNA genes via a yet undiscovered mechanism. In a recent study, a different truncation of the Kcnq1ot1 RNA also resulted in disruption of paternal silencing; however, normal imprinted expression of one gene (Cdkn1c) was observed in a subset of mouse embryonic tissues (Shin et al., 2008). This finding led the authors to propose that silencing at the Kcnq1 locus involves two mechanisms: one dependent on Kcnq1ot1 RNA and one independent.

Genomic imprinting by Air and Kcnq1ot1 RNAs could occur through a variety of mechanisms; in fact, it is formally possible that silencing occurs due to the act of transcribing the ncRNAs, as opposed to the action of the ncRNAs themselves (reviewed in (Pauler et al., 2007; Royo and Cavaille, 2008)). Models that invoke the ncRNAs as mediators of silencing describe them as agents that direct recruitment of factors that add layers of repressive histone modifications or DNA methylations to specific regions of the genome. Other models suggest that RNAi is involved in silencing imprinted genes. Still other models propose that transcription of the ncRNA interferes with the function of a cis-acting DNA regulatory element that is responsible for controlling expression of all imprinted mRNA genes in a particular cluster. In this model, the ncRNA itself would have no role in silencing. Future experiments, especially those that separately test the function of transcription versus the ncRNA, will be needed to further unravel the roles of ncRNAs in allele-specific transcriptional silencing.

Mouse H19 ICR ncRNAs

Igf2/H19 is another imprinted gene locus that has been widely investigated, and recent studies have identified new ncRNAs transcribed from this locus that function in silencing, however, their characteristics are distinctly different from the Air and Kcnq1ot1 RNAs (Schoenfelder et al., 2007). At this locus, the Igf2 gene is protein-encoding and paternally expressed, while the H19 gene is non-coding and its transcript is maternally expressed (Pauler et al., 2007). Unlike the examples of Air RNA and Kcnq1ot1 RNA discussed above, it appears that the H19 RNA does not function in imprinting at the Igf2 locus. Experiments in which the entire H19 promoter and gene were conditionally deleted in mice had little or no effect on Igf2 imprinting (Schmidt et al., 1999). Recently, new ncRNAs transcribed from the mouse Igf2/H19 locus have been discovered (Schoenfelder et al., 2007). These ncRNAs are transcribed in both directions from the H19 ICR (imprinting control region) on both the maternal and paternal alleles (Figure 2). The ICR is a DNA element that functions in controlling monoallelic expression through differential epigenetic marks on either the paternal or maternal allele (Pauler et al., 2007). Although the H19 ICR ncRNAs were documented in mice, the experiments to characterize their function were performed in a model transgenic Drosophila line carrying a mouse H19 locus that silences expression of a reporter gene. The H19 ICR ncRNAs were transcribed from this locus in Drosophila, and knockdown of the ncRNAs by siRNA resulted in the loss of silencing of the reporter gene (Schoenfelder et al., 2007). The mechanism for how the H19 ICR ncRNAs mediate silencing is unknown; however, silencing of the reporter gene was unaffected by mutations in RNAi pathway genes. Future studies in mice will be needed to test whether the H19 ICR ncRNAs establish monoallelic transcription at the Igf2/H19 locus, and if so, determine the mechanism by which this occurs.

Establishing dosage compensation

Dosage compensation is the means by which organisms equalize levels of gene expression from the sex chromosomes in males and females. Although the mechanisms for establishing dosage compensation differ between mammals and Drosophila, they are similar in that ncRNAs are involved in the process. Mammals achieve dosage compensation by silencing one of the X chromosomes in females via the action of ncRNAs named Xist and Tsix. By contrast, Drosophila elevate levels of transcription from the single male X chromosome via the action of the roX RNAs. The functions of ncRNAs in mammalian and Drosophila dosage compensation are discussed below.

Mouse Xist and Tsix RNAs

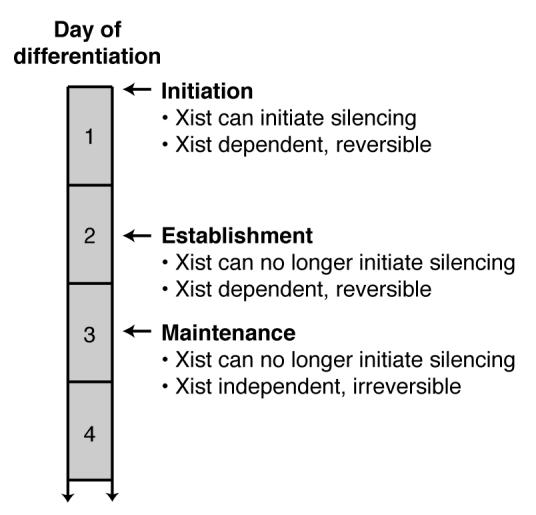

Xist (X inactive specific transcript) is an ncRNA that causes X chromosome inactivation (XCI), in which one of the female X chromosomes in transcriptionally silenced. Mouse Xist is 15-17 kb, spliced, polyadenylated, and is associated exclusively with the inactive X chromosome (reviewed in (Heard and Disteche, 2006)). In female embryos, Xist transcription is upregulated on the future inactive X chromosome, and Xist RNA coats the chromosome by associating with the chromatin in the vicinity of its transcription site. Xist initiates XCI by facilitating the recruitment of silencing factors such as Polycomb group proteins that modify histones (Figure 3) (Plath et al., 2003; Silva et al., 2003). As a result, following Xist expression, histones on the X chromosome lose modifications that mark transcriptionally active chromatin (e.g. acetylation of histone H3 lysine 9), and gain modifications that mark transcriptionally inactive chromatin (e.g. hypermethylation of histone H3 lysine 9). Ultimately, layers of chromatin modifications such as histone methylation, histone ubiquitinylation, and deposition of histone variants, spread across the entire X chromosome from which Xist was transcribed and lead to a silent heterochromatic state (Heard and Disteche, 2006).

Figure 3.

A schematic describing three steps in the process of X chromosome inactivation with respect to the numbers of days after mouse embryonic stem cells begin differentiation. Reversible means that continued Xist expression is required to prevent losing transcriptional silencing. Adapted from Figure 6 in (Plath et al., 2002).

Several lines of evidence support the model that Xist RNA itself is a key mediator of this process (Prasanth and Spector, 2007). First, Xist physically associates with the silent chromosome and the nuclear matrix around it (Heard and Disteche, 2006). Second, recruitment of Polycomb group proteins requires Xist RNA (Plath et al., 2003; Silva et al., 2003). Third, an autosome that contains the Xist transgene is silenced when the Xist RNA is expressed (Lee and Jaenisch, 1997). Lastly, a discrete region near the 5′ end Xist RNA is required for silencing, and other distinct regions are required for chromosomal association. Deleting the element required for silencing, results in Xist RNA that still associates with chromatin and coats the chromosome, but does not regulate repression of transcription (Wutz et al., 2002).

Xist is not the only ncRNA that is critical for proper execution of XCI — it works in conjunction with the Tsix RNA. Tsix is the antisense transcript of Xist, and their expression on a given X chromosome is mutually exclusive (Lee et al., 1999). Tsix expression protects the active X chromosome from inactivation by Xist RNA (Heard and Disteche, 2006). At the onset of differentiation, Tsix RNA expression persists on the future active X chromosome, and expression ceases on the future inactive X chromosome. This loss of Tsix expression allows for the upregulation of Xist RNA and its spreading along the future inactive X chromosome. The precise mechanism by which Tsix regulates Xist has not yet been deciphered; however, the recent study described next provides a compelling model.

The complementarity between Xist and Tsix RNAs has been suggestive of the formation of dsRNA and a role for the RNAi pathway in XCI. A recent report by Lee and colleagues demonstrates that this is likely the case (Ogawa et al., 2008). Using mouse embryonic stem cells, they detected short RNAs between 25 and 42 nt in length containing Xist/Tsix sequences. These short RNAs were tightly regulated; they were only detected while XCI was being established. Interestingly, double stranded Tsix/Xist RNA was detected before XCI and decreased as XCI proceeded, suggesting that the dsRNA was the precursor of the short RNAs (Ogawa et al., 2008). A link between XCI and the RNAi machinery was established from experiments in which female embryonic stem cells lacking Dicer showed diminished levels of the short RNAs, and also showed increased Xist RNA expression. The authors propose a model whereby Tsix/Xist dsRNA initially forms at both X chromosomes. During XCI, continued expression of Tsix from the active X chromosome leads to dsRNA that is processed to short RNAs, which then silence the Xist gene via a mechanism akin to transcriptional gene silencing (reviewed in (Hawkins and Morris, 2008)). This would keep the chromosome active. On the inactive X chromosome, Tsix expression does not occur, therefore Xist is transcribed and silences the chromosome as described previously.

Drosophila roX RNAs

Dosage compensation in Drosophila is different from mammals, in that it involves upregulating expression from the single male X chromosome; however, like mammals, ncRNAs are also involved. The ncRNA, either roX1 or roX2 (RNA on the X1 or X2, respectively) is part of a protein-RNA complex named MSL (male specific lethal) that binds to hundreds of sites on the male X chromosome (Deng and Meller, 2006). One of the MSL subunits, MOF (male absent on first), is a histone acetyltransferase and acetylation of histone H4 lysine 16 is enriched in regions of the male X chromosome (Deng and Meller, 2006). roX1 and roX2 are functionally redundant; dosage compensation and the proper binding of MSL to the X chromosome require either roX1 or roX2. There is little sequence similarity between roX1 (3.7 kb) and roX2 (multiple spliced forms, with the predominant form being 0.5 kb), and in the case of roX1, only relatively short regions at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the RNA are required for dosage compensation (Stuckenholz et al., 2003; Deng et al., 2005). Both ncRNAs are expressed from the X chromosome exclusively in males, with the exception of a short 2 hour window after egg laying during which roX1 is also expressed in females (Meller, 2003). When either roX1 or roX2 is expressed from a transgene on an autosome, transcription from the male X chromosome is upregulated and dosage compensation occurs (Meller and Rattner, 2002); therefore, these ncRNAs can activate transcription in trans. Additional studies will likely reveal the mechanism by which the roX RNAs aid in localizing the MSL complex to the male X chromosome, as well as their precise role in upregulating transcription.

Altering chromatin at developmental loci

The Hox loci, which contain genes encoding proteins that orchestrate development in animals, are among the best studied systems of coordinated transcriptional regulation. It has been known for over two decades that ncRNAs are synthesized from the Hox loci in Drosophila (Lipshitz et al., 1987). Recent studies have also identified Hox ncRNAs in humans, as well as additional Hox ncRNAs in flies, and have begun to shed light on their function. The view, however, is murky — especially in flies — due to two reports that contain seemingly conflicting results. We first summarize these two reports on Drosophila Hox ncRNAs and then discuss a report describing a function for a human Hox ncRNA.

Drosophila Hox ncRNAs

Sauer and colleagues reported that ncRNAs transcribed from TREs (trithorax response elements) in the fly Hox loci recruit the Ash1 protein, a histone methyl transferase, to the ultrabithorax (Ubx) gene, thereby activating its transcription in larval imaginal discs (Sanchez-Elsner et al., 2006). Three ncRNAs were identified (tre1-3) that ranged in size from 350 to 1109 nt. Each of the ncRNAs bound directly to Ash1 in vitro and associated with the protein in cells. Treatment with siRNAs targeting the tre ncRNAs lowered Ubx transcription and reduced recruitment of Ash1 to the TREs. tre ncRNAs that were expressed from a transfected plasmid in Drosophila S2 cells localized to the genomic TREs and caused recruitment of Ash1. Together these results led to a model in which the tre ncRNAs recruit Ash1 to the TREs in larval cells, causing activation of Ubx transcription (Sanchez-Elsner et al., 2006).

Mazo and colleagues subsequently published a seemingly conflicting report in which they concluded that transcription of ncRNAs from the Ubx loci (but not the ncRNAs themselves) caused repression of Ubx gene transcription (Petruk et al., 2006). They investigated several ncRNAs transcribed from the intergenic region upstream of the Ubx gene, including the tre RNAs described above. Experiments showed that although the ncRNAs and the Ubx mRNA are present in embryos at the same time, they are not found in the same cells. siRNA knockdown of the ncRNAs did not affect Ubx mRNA transcription, but eliminating transcription of the ncRNA genes by promoter knockout caused expression of the Ubx mRNA (Petruk et al., 2006). These results led to a transcriptional interference model in which the process of transcribing the ncRNA genes represses Ubx mRNA transcription, and the ncRNAs themselves do not function as regulators of Ubx transcription.

Both the Sauer and Mazo papers provide compelling evidence to support their respective models. Clearly, further study will be needed to clarify the relative importance of Hox ncRNAs and transcriptional interference in setting levels of Ubx transcription in individual cells during Drosophila development. A recent review provides a detailed discussion of the published results and current debate in this field, as well as describes a hypothetical model that can reconcile some of the seemingly conflicting experimental results by taking developmental timing into account (Lempradl and Ringrose, 2008).

Human HOTAIR RNA

ncRNAs arising from the human Hox loci have recently been identified (Rinn et al., 2007; Sessa et al., 2007), and one such ncRNA has been found to control transcription (Rinn et al., 2007). Chang and colleagues reported that an ncRNA named HOTAIR (Hox antisense intergenic RNA), which is a 2.2 kb transcript made from the HOXC locus on chromosome 12, acts in trans to silence transcription across the 40 kb HOXD locus on chromosome 2 (Rinn et al., 2007). siRNA knockdown of HOTAIR caused multiple changes throughout the HOXD locus including: increased transcription, decreased trimethylation of H3 lysine 27, and decreased occupancy of Suz12, a protein in the histone modifying Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2). HOTAIR was also found to co-immunoprecipitate with Suz12. The results lead to a model in which HOTAIR is made from the HOXC locus and recruits PRC2 to the HOXD locus (via an unknown mechanism), leading to trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 and transcriptional silencing (Rinn et al., 2007). This ncRNA is unique in that it acts in trans to silence chromosomal domains. Future studies will likely reveal whether a similar mechanism is used by this or other ncRNAs to silence transcription at specific loci throughout the genome.

Silencing individual genes through chromatin modification

Mouse rRNA IGS ncRNAs

The genes from which mammalian ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is transcribed contain intergenic spacer (IGS) sequences that possess promoters for Pol I. rRNA genes exist in tandem arrays, and a significant portion of these genes are maintained in a transcriptionally silent heterochromatic state (Santoro, 2005). A recent study has shown that ncRNAs transcribed by Pol I from IGS sequences contribute to silencing rRNA genes (Mayer et al., 2006). The primary factor responsible for establishing this silent state is NoRC (nucleolar remodeling complex), which is an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler that can recruit histone modifiers and DNA methylation enzymes (Santoro, 2005). Experiments showed that association of NoRC with chromatin required interaction with RNA, which was mediated by its TIP5 subunit (Mayer et al., 2006). In vitro binding assays then showed that TIP5 tightly and specifically bound ncRNAs with sequences matching those of the rRNA gene promoter. Analysis of RNA from mouse cells revealed transcripts that originated from IGS sequences and contained regions that matched rRNA gene promoter sequences, as well as shorter RNAs that contained promoter sequences. The IGS ncRNAs co-immunoprecipitated with overexpressed NoRC from cells. Knockdown of the IGS transcripts derepressed transcription from rRNA genes, decreased histone modifications associated with silent chromatin, and disrupted nucleolar localization of NoRC (Mayer et al., 2006). This study provides another example of how ncRNAs are able to control transcription by mediating the recruitment of protein factors that modify chromatin.

Human p15AS RNA

Recently, an antisense transcript from the p15 gene (p15AS RNA) was discovered to function in transcriptional silencing (Yu et al., 2008). p15 is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that acts as a tumor suppressor (Nobori et al., 1994). In many cancers the p15 gene is silenced, although the mechanism by which this occurs was unknown (Lubbert, 2003). Feinberg, Cui, and colleagues hypothesized that the p15AS RNA is involved in silencing the p15 gene in tumor cells (Yu et al., 2008). They found that p15AS levels were elevated in leukemia cell lines, whereas p15 mRNA levels were decreased. Additionally, heterochromatic markers consistent with silencing were observed on the p15 gene in the leukemia cell lines (Yu et al., 2008). When p15AS was overexpressed in cells, the p15 gene was silenced and the silencing was maintained even after expression of p15AS was eliminated, suggesting that p15AS is involved in initiating silencing as opposed to maintaining silencing. Given the sequence complementarity between the p15 mRNA and the p15AS RNA, it seemed possible that the RNAi pathway would be involved in silencing p15 transcription. In mouse embryonic stem cells lacking Dicer, however, p15AS-induced silencing of the p15 gene still occurred efficiently (Yu et al., 2008). A molecular picture of how p15AS mediates silencing has yet to be revealed. Given that antisense partners exist for up to 70% of transcripts in cells (Katayama et al., 2005), the example of p15AS provides an intriguing model for how other antisense transcripts might function to control transcription.

ncRNAs that modulate transcriptional activator or coactivator function

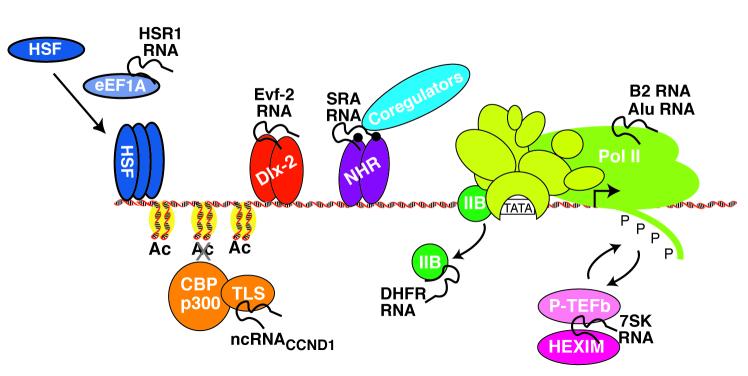

In general, transcriptional activators and coactivators function at many genes. Therefore, the ncRNAs that regulate the activities of activators or coactivators have the potential to control entire transcriptional programs in cells. By contrast, it is also possible for an ncRNA to control the activity of a single gene by targeting an activator or coactivator that acts at the locus from which the ncRNA is transcribed. As a group, the ncRNAs described below utilize both mechanisms (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A model depicting the protein targets of several ncRNAs that regulate Pol II transcription. ncRNAs have been shown to regulate transcription using mechanisms as diverse as controlling: chromatin modifications, the oligomerization state of an activator, interactions with co-regulators, sequestration in RNPs, and the activity of Pol II itself. Figure 1 indicates whether these ncRNAs stimulate or repress transcription. See the text for a more detailed description of each ncRNA and how it regulates transcription.

Controlling transcriptional activators

Mouse Evf-2 RNA

Vertebrate Dlx genes encode homeodomain proteins that function as transcriptional activators during neuronal differentiation and brain and limb patterning (Panganiban and Rubenstein, 2002). The Dlx genes are expressed in bigene clusters, which contain highly conserved enhancers in the intergenic region that separates the two genes in the cluster. Studies found that an ncRNA named Evf-2 was transcribed in a developmentally regulated manner from the highly conserved intergenic region in the Dlx-5/6 cluster (Feng et al., 2006). Indications of a function for the Evf-2 RNA came from experiments showing that its expression was tightly linked to expression of the Dlx-5 and Dlx-6 genes. Further experiments in mouse neuronal cells showed that the Evf-2 RNA plays a role in activating Dlx-5/6 expression; knocking down Evf-2 using siRNAs eliminated Dlx-5/6 transcriptional activation. Evf-2 RNA elicits it effects through interaction with Dlx-2, a homeodomain transcription factor known to induce brain patterning by upregulating the expression of Dlx-5/6 (Panganiban and Rubenstein, 2002). The Evf-2 RNA and the Dlx-2 protein form a complex inside cells, which is thought to stabilize the interaction between Dlx-2 and its target sequences in the Dlx-5/6 enhancer (Feng et al., 2006). The complex between Dlx-2 and Evf-2 activates transcription in a target and homeodomain specific manner. For example, Evf-2 RNA cannot coactivate the transcription of homeodomain proteins other than Dlx-2, and Evf-2 does not cooperate with Dlx-2 to activate transcription from enhancers other than Dlx-5/6 (Feng et al., 2006). Therefore, Evf-2 RNA functions as a localized transcriptional coactivator.

Mammalian HSR1 RNA

Transcription of mRNAs encoding mammalian heat shock proteins is rapidly and highly upregulated during heat shock and other types of cell stress (Morimoto, 1998). A primary regulator of this process is the transcriptional activator HSF1 (heat shock factor 1). Prior to heat shock HSF1 is predominantly monomeric, which is its inactive conformation. In response to heat shock, HSF1 is localized in the nucleus as a homotrimer where it is bound to specific DNA elements in the promoters of genes upregulated in response to heat shock (Voellmy, 2004). A search for factors that regulate HSF1 activity revealed an ncRNA, named heat shock RNA 1 (HSR1) (Shamovsky et al., 2006). Experiments showed that HSR1 works in conjunction with the translation factor eEF1A to promote HSF1 trimerization and DNA binding; neither factor alone was sufficient to activate HSF1. Decreasing levels of HSR1 in mammalian cells by antisense or siRNA resulted in loss of products from heat-shock activated genes, and decreased survival after prolonged heat shock (Shamovsky et al., 2006). It appears that mammalian cells have evolved to use ncRNAs as key regulators of gene expression during cell stress since several ncRNAs have now been discovered to regulate transcription during the mammalian cell stress response: HSR1, 7SK, and B2/Alu RNAs (the latter three are discussed later). Interestingly, these ncRNAs target distinctly different steps in the transcription process and regulate different classes of genes.

Coregulating transcription

Human SRA RNA

Steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA) was one of the first ncRNAs discovered as a regulator of Pol II transcription (Lanz et al., 1999). It functions as a coregulator for nuclear receptors, which are ligand-activated transcription factors (e.g. the estrogen, glucocorticoid, and vitamin D receptors). The transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors is heavily controlled by coregulators (reviewed in (McKenna and O’Malley, 2002)). SRA is thought to function as an ncRNA scaffold, using several stem-loop structures to bring together nuclear receptors and protein coregulators at target genes (Colley et al., 2008). Although first identified as a coactivator for nuclear receptors, SRA has now been shown to mediate transcriptional repression as well. To add another layer of complexity to SRA’s ability to control transcription, this ncRNA is subject to post-transcriptional modification. SRA is the substrate for two pseudouridine synthases, enzymes that catalyze the isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine (Zhao et al., 2004). The prevailing model is that differential pseudouridylation of SRA by the two enzymes acts as a regulatory switch to influence SRA’s ability to interact with coregulator proteins (Zhao et al., 2007).

SRA interacts with a diverse set of coregulator proteins to mediate nuclear receptor-driven transcription, and new ones continue to be identified. For example, a search for novel SRA-binding proteins identified SLIRP (SRA Stem-Loop Interacting RNA binding Protein) (Hatchell et al., 2006). SLIRP functions as a corepressor in an SRA-dependent manner, and SLIRP recruitment to endogenous nuclear receptor-dependent promoters requires SRA. In a second example, a nuclear receptor corepressor named SHARP (SMRT/HDAC1 Associated Repressor Protein) was found to interact with SRA through three RNA recognition motifs (Shi et al., 2001). These motifs are required for SHARP to repress SRA-mediated nuclear receptor activity. Thirdly, the RNA binding DEAD-box proteins p68/p72 were found to bind SRA in vitro and co-purify with SRA from cell extracts (Watanabe et al., 2001). Experiments in cells showed that p68/p72 function with SRA to coactive transcription mediated by the estrogen receptor. Interestingly, SRA along with p68/p72 also function as coactivators of MyoD, a transcription factor that facilitates muscle cell differentiation, but is not a member of the nuclear hormone receptor family (Caretti et al., 2006). These findings suggest that SRA is a general transcriptional coregulator that likely controls the expression of many genes.

Human ncRNACCND1

While searching for regulators of histone acetyltransferases, an RNA binding protein named TLS was found to associate with CBP and p300 and inhibit their acetyltransferase activities (Wang et al., 2008). The inhibition was sensitive to RNase treatment in vitro, indicating that the function of TLS in regulating CBP/p300 is RNA dependent. Subsequent cell-based studies showed that TLS is recruited to the cyclin D1 gene (CCND1) and that siRNA knockdown of TLS increased both CCND1 mRNA and levels of acetylated histone H3 at the CCND1 promoter (Wang et al., 2008). The authors searched for ncRNAs transcribed from the CCND1 upstream region that could potentially regulate TLS — the idea being that an ncRNA transcribed locally could bind TLS at the CCND1 promoter and cause it to decrease the acetyltransferase activity of CBP/p300, thereby lowering CCND1 mRNA transcription. The authors identified multiple ncRNAs (as a group named ncRNACCND1) that are transcribed from the CCDN1 upstream region and induced by ionizing radiation, a condition under which CCND1 transcription is downregulated (Wang et al., 2008). ncRNACCND1 are polyadenylated but not capped, heterogeneous in size (200 nt, 330 nt, and larger), present at a low copy number (2-4 copies per cell), and mainly associated with chromatin, perhaps via regions of RNA-DNA hybrid. RNA oligonucleotides corresponding to regions of ncRNACCND1 bound TLS in vitro and caused TLS to inhibit p300 histone acetyltransferase activity. Knockdown of ncRNACCND1 by siRNA decreased TLS recruitment to the CCND1 promoter, increased acetylation of histone H3 lysine 9 and lysine 14, and increased levels of CCND1 mRNA (Wang et al., 2008). These results led to a model in which ncRNACCND1 act at the CCND1 gene by binding to and activating TLS. In its active form, TLS binds CBP/p300 and inhibits their acetyltransferase activities, which decreases histone H3 acetylation and lowers CCND1 mRNA transcription.

ncRNAs that control the formation or activity of transcription complexes

The ncRNAs below all regulate components of the general transcription machinery; therefore, they have the potential to control transcription of many genes across the genome (Figure 4). Indeed, all but one of the ncRNAs act as trans factors that broadly regulate transcription. The exception is the DHFR ncRNA, which is thought to act near its site of synthesis in a gene-specific fashion. Three of the ncRNAs described below (6S, B2, and Alu RNAs) function as trans repressors of the polymerase itself and globally control transcription in response to changing cellular conditions, yet they are from organisms as distant as bacteria and humans.

DHFR ncRNA controls the activity of a general transcription factor

The human DHFR gene contains two promoters. The downstream major promoter directs transcription of the DHFR mRNA, while the upstream minor promoter directs synthesis, at a much lower level, of an ncRNA that terminates within the second intron of the DHFR gene (Martianov et al., 2007). In vitro transcription assays revealed that when these two promoters were in tandem, with the minor promoter upstream, transcription from the major promoter was inhibited. The DHFR ncRNA interacted directly with the general transcription factor TFIIB in vitro, and this interaction destabilized preinitiation complexes at the major DHFR promoter (Martianov et al., 2007). Moreover in cells, ChIP assays revealed decreased occupancy of TFIIB at the major promoter that depended on the presence of both the minor promoter and the ncRNA transcribed from it. Interestingly, a stable triplex structure between the DHFR ncRNA and the DNA of the major promoter was observed in vitro, supporting a model in which formation of the triplex on chromatin might facilitate promoter targeting and transcriptional repression in cells (Martianov et al., 2007). Recent studies have revealed an abundance of transcripts that originate from the upstream promoter regions of genes (Guenther et al., 2007; Kapranov et al., 2007a). Given this observation, it is possible that the mechanism of transcriptional regulation described for the DHFR gene could occur elsewhere in the genome.

Controlling RNA polymerase activity

Bacterial 6S RNA

Bacterial RNA polymerases (RNAPs) contain a dissociable subunit, the σ subunit, which together with the core enzyme, binds the promoters of genes, melts the DNA to form open complexes, and initiates transcription (Mooney et al., 2005). The predominant σ factor in E. coli is σ70. 6S RNA is a bacterial ncRNA that binds the σ70-RNAP to represses transcription in late stationary phase (Wassarman and Storz, 2000). The secondary structure of 6S RNA contains a single-stranded bulge that mimics the conformation of melted promoter DNA (Barrick et al., 2005; Trotochaud and Wassarman, 2005). Mechanistic studies showed that 6S RNA represses transcription by preventing σ70-RNAP from binding to promoter DNA (Wassarman and Saecker, 2006). Surprisingly, 6S RNA serves as a template for RNA-dependent RNA synthesis (Wassarman and Saecker, 2006; Gildehaus et al., 2007). In vitro experiments showed that RNAP produced 14-20 nt de novo transcripts named pRNAs that initiated from a specific site within the bulge region of 6S RNA (Wassarman and Saecker, 2006). Upon synthesis of pRNAs, the σ70 subunit was released and the remaining complex between core RNAP and 6S RNA was unstable. This suggests that synthesis of pRNA releases RNAP from 6S RNA, thereby derepressing transcription. Consistent with this model, 6S RNA/pRNA hybrids were detected in extracts prepared from E. coli cells that had been released from stationary phase (Wassarman and Saecker, 2006). Hence, the transcriptional repressor 6S RNA serves as a template for the synthesis of its own derepressive RNA.

Mouse B2 RNA and Human Alu RNA

Mouse B2 RNA and human Alu RNA are discussed together because they share a common function as general transcriptional repressors in response to heat shock, although these ncRNAs are not similar in sequence or secondary structure (Allen et al., 2004; Espinoza et al., 2007; Mariner et al., 2008). The abundance of B2 and Alu RNAs increases sharply in response to heat shock and other cellular stresses (Liu et al., 1995). B2 and Alu RNAs were found to bind tightly to Pol II and function as transcriptional repressors of mRNA genes in response to heat shock in mouse or human cells, respectively (Allen et al., 2004; Espinoza et al., 2004; Mariner et al., 2008). The interaction between Pol II and the ncRNAs occurs with low nM affinity in vitro and does not require other factors, although the interaction is likely to be regulated inside cells, such that transcriptional repression in response to heat shock is promoter-selective. The ncRNAs do not prevent the polymerase from being recruited to promoter DNA; instead, biochemical experiments showed that B2 and Alu RNAs enter complexes with Pol II at promoters where they repress RNA synthesis (Espinoza et al., 2004; Mariner et al., 2008). Consistent with this finding, ChIP assays in mouse and human cells showed an increase in the occupancy of Pol II at the promoters of repressed genes upon heat shock. In addition, B2 and Alu RNAs were found to occupy the promoters of genes repressed during heat shock in mouse and human cells, respectively, using a modified ChIP assay designed to detect the locations of ncRNAs associated with chromatin in cells (Mariner et al., 2008). Experiments indicate that B2 or Alu RNA, while allowing complexes to form at promoters, keeps Pol II from properly interacting with promoter DNA, thereby repressing transcription (Espinoza et al., 2007).

Deletion analysis has defined regions of B2 and Alu RNAs that are involved in either high-affinity binding to Pol II or transcriptional repression. Within each ncRNA these regions are distinct from one another; removing a region required for transcriptional repression results in an ncRNA that can still bind tightly to Pol II and assemble into complexes on promoter DNA, however, cannot repress transcription (Espinoza et al., 2007; Mariner et al., 2008). Interestingly, the regions of Alu RNA that repress transcription are modular: they can be fused to an ncRNA that binds Pol II and enable that RNA to inhibit transcription (Mariner et al., 2008). This property is reminiscent of protein transcriptional regulators, which have DNA binding domains and regulatory domains that can be mixed and matched.

The similarities between the mechanisms by which mammalian B2/Alu RNAs and bacterial 6S RNA repress transcription are striking, but perhaps not surprising; mammalian and bacterial protein transcriptional regulators share may features. B2, Alu, and 6S RNAs all bind directly to an RNA polymerase, block the ability of the polymerase to properly associate with promoter DNA, and as a result repress transcription. Moreover, all three ncRNAs act as somewhat global repressors of transcription in response to a specific cellular condition (e.g. they act at many genes as opposed to acting locally at one or two). It remains to be determined how repression by B2 and Alu RNAs is overcome when mouse and human cells recover from heat shock. It is possible that the mechanism(s) will involve RNA-directed RNA synthesis, and as such, be related to the mechanism used by bacterial RNAP to recover from 6S RNA-mediated repression during the exit from stationary phase.

Human RNase P (H1 RNA)

RNase P has long been recognized as an important factor involved in tRNA processing; it functions to remove 5′ leader sequences from precursor tRNAs (Xiao et al., 2002). Eukaryotic RNase P is a large ribonucleoprotein complex that consists of a catalytic RNA (H1 RNA) and approximately 10 protein subunits. More recently, a new function for RNase P in controlling transcription by Pol III has been revealed (Reiner et al., 2006). The precise role of H1 RNA in this process, compared to the protein subunits of RNase P, has not yet been defined; nonetheless this study defines an exciting new function for a ribonucleoprotein complex as a transcriptional regulator.

Studies found that RNase P enzymatic activity co-immunoprecipitated with Pol III from human cells (Reiner et al., 2006). Further in vitro experiments revealed that nuclear extracts depleted of RNase P no longer supported transcription of tRNA genes as well as several other ncRNA genes transcribed by Pol III. Moreover, addition of exogenous partially purified RNase P to depleted extracts restored Pol III activity in a manner dependent on intact H1 RNA. ChIP assays showed that RNase P subunits localized to tRNA and 5S rRNA genes, but not to U6 snRNA or 7SL genes in cells (Reiner et al., 2006). siRNAs targeting various subunits of RNase P inhibited Pol III transcription in human cells; however, Pol III could still occupy the promoters of tRNA and 5S rRNA genes after siRNA treatment. This suggests that RNase P is not required for Pol III recruitment to these genes, but it is required a subsequent step in the transcription reaction. The authors propose a model in which RNase P acts as a general transcription factor for Pol III (Reiner et al., 2006). The precise mechanism by which RNase P controls transcription by Pol III, the role of H1 RNA in the process, and whether Pol III transcription can be coupled to tRNA processing remain to be determined.

7SK RNA controls transcript elongation

7SK snRNA plays a role in regulating the availability of the transcription factor P-TEFb (positive transcription elongation factor b), which controls transcript elongation at most mRNA genes (Peterlin and Price, 2006). P-TEFb is a cyclin-dependent kinase that phosphorylates the C-terminal domain of Pol II, thereby allowing productive elongation and co-transcriptional mRNA processing (Peterlin and Price, 2006). A role for 7SK snRNA in transcription was initially revealed when it was found to bind to P-TEFb and inhibit its kinase activity (Nguyen et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001). Subsequent studies found that 7SK snRNA negatively regulates P-TEFb by sequestering it in an snRNP complex that also contains the protein HEXIM1 or HEXIM2 (Yik et al., 2003; Michels et al., 2004). The inactive complex containing P-TEFb, 7SK RNA, and HEXIM predominates over free P-TEFb in many cell lines, and the release of P-TEFb from this complex occurs when cells are treated with stress-inducing agents, such as actinomycin D (Yik et al., 2003). Therefore, 7SK regulates the reservoir of P-TEFb by controlling the equilibrium between its active and inactive forms; this equilibrium is thought to be important for cell growth and viability (Peterlin and Price, 2006).

Two recent reports provide insight into how disruption of the 7SK snRNP allows cells to respond to changing growth conditions and transcriptional demand. One study found that a La-related protein, PIP7S, stably associates with the 7SK snRNP (He et al., 2008). Loss of PIP7S, which occurs in many tumors, shifts the P-TEFb equilibrium to the active state and results in malignant transformation. A second report revealed that in response to UV treatment, two phosphatases involved in Ca2+-dependent signaling (PP2B and PP1α) work cooperatively to dephosphorylate P-TEFb, resulting in disruption of the 7SK snRNP (Chen et al., 2008). This allows P-TEFb to be recruited to promoters where it can regulate transcript elongation. Therefore, controlling the formation and disruption of the 7SK snRNP is critical for regulating the amount of active P-TEFb, which globally controls transcript elongation.

Concluding remarks

ncRNAs are now known to be key regulators of transcription, and as a group function at many different levels from regulating chromatin structure to controlling transcript elongation. To date only a limited number of ncRNA transcriptional regulators have been identified in a small set of organisms; however, the observations that different ncRNAs with related functions have been identified in a single organism (e.g. Air and Kcnq1ot1 RNAs) and that ncRNAs with similar function have been identified in diverse organisms (e.g. bacterial 6S RNA, mouse B2 RNA, and human Alu RNA) support the notion that ncRNAs will ultimately be discovered as pervasive regulators of transcription across biology. Since RNAs with little sequence similarity can have similar function, identifying transcriptional regulatory ncRNAs that share a function in different or similar species might be more difficult than identifying homologous proteins, which have often been found by sequence comparison. Given the vast number of ncRNAs now known to exist in cells, most with unknown function, we imagine that many are ncRNA transcriptional regulators awaiting discovery.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Public Health Service grant (R01 GM068414) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

References

- Allen TA, Von Kaenel S, Goodrich JA, Kugel JF. The SINE-encoded mouse B2 RNA represses mRNA transcription in response to heat shock. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:816–821. doi: 10.1038/nsmb813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick JE, Sudarsan N, Weinberg Z, Ruzzo WL, Breaker RR. 6S RNA is a widespread regulator of eubacterial RNA polymerase that resembles an open promoter. RNA. 2005;11:774–784. doi: 10.1261/rna.7286705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhler M, Moazed D. Transcription and RNAi in heterochromatic gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1041–1048. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caretti G, Schiltz RL, Dilworth FJ, Di Padova M, Zhao P, Ogryzko V, Fuller-Pace FV, Hoffman EP, Tapscott SJ, Sartorelli V. The RNA helicases p68/p72 and the noncoding RNA SRA are coregulators of MyoD and skeletal muscle differentiation. Dev Cell. 2006;11:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y. Noncoding RNA transcription beyond annotated genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, et al. PP2B and PP1alpha cooperatively disrupt 7SK snRNP to release P-TEFb for transcription in response to Ca2+ signaling. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1356–1368. doi: 10.1101/gad.1636008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley SM, Iyer KR, Leedman PJ. The RNA coregulator SRA, its binding proteins and nuclear receptor signaling activity. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:159–164. doi: 10.1002/iub.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Meller VH. Non-coding RNA in fly dosage compensation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Rattner BP, Souter S, Meller VH. The severity of roX1 mutations is predicted by MSL localization on the X chromosome. Mech Dev. 2005;122:1094–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza CA, Allen TA, Hieb AR, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. B2 RNA binds directly to RNA polymerase II to repress transcript synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nsmb812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza CA, Goodrich JA, Kugel JF. Characterization of the structure, function, and mechanism of B2 RNA, an ncRNA repressor of RNA polymerase II transcription. RNA. 2007;13:583–596. doi: 10.1261/rna.310307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Bi C, Clark BS, Mady R, Shah P, Kohtz JD. The Evf-2 noncoding RNA is transcribed from the Dlx-5/6 ultraconserved region and functions as a Dlx-2 transcriptional coactivator. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1470–1484. doi: 10.1101/gad.1416106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick GV, Soloway PD, Higgins MJ. Regional loss of imprinting and growth deficiency in mice with a targeted deletion of KvDMR1. Nat Genet. 2002;32:426–431. doi: 10.1038/ng988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiduschek EP, Kassavetis GA. Comparing transcriptional initiation by RNA polymerases I and III. Curr Opin in Cell Biol. 1995;7:344–351. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildehaus N, Neusser T, Wurm R, Wagner R. Studies on the function of the riboregulator 6S RNA from E. coli: RNA polymerase binding, inhibition of in vitro transcription and synthesis of RNA-directed de novo transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1885–1896. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SI, Moazed D. Heterochromatin and epigenetic control of gene expression. Science. 2003;301:798–802. doi: 10.1126/science.1086887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG, Levine SS, Boyer LA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchell EC, et al. SLIRP, a small SRA binding protein, is a nuclear receptor corepressor. Mol Cell. 2006;22:657–668. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins PG, Morris KV. RNA and transcriptional modulation of gene expression. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:602–607. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He N, Jahchan NS, Hong E, Li Q, Bayfield MA, Maraia RJ, Luo K, Zhou Q. A La-related protein modulates 7SK snRNP integrity to suppress P-TEFb-dependent transcriptional elongation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell. 2008;29:588–599. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard E, Disteche CM. Dosage compensation in mammals: fine-tuning the expression of the X chromosome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1848–1867. doi: 10.1101/gad.1422906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadonaga JT. Regulation of RNA polymerase II transcription by sequence-specific DNA binding factors. Cell. 2004;116:247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P, et al. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science. 2007a;316:1484–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1138341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P, Willingham AT, Gingeras TR. Genome-wide transcription and the implications for genomic organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2007b;8:413–423. doi: 10.1038/nrg2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama S, et al. Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science. 2005;309:1564–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1112009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz RB, McKenna NJ, Onate SA, Albrecht U, Wong J, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. A steroid receptor coactivator, SRA, functions as an RNA and is present in an SRC-1 complex. Cell. 1999;97:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, Davidow LS, Warshawsky D. Tsix, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nat Genet. 1999;21:400–404. doi: 10.1038/7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, Jaenisch R. Long-range cis effects of ectopic X-inactivation centres on a mouse autosome. Nature. 1997;386:275–279. doi: 10.1038/386275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempradl A, Ringrose L. How does noncoding transcription regulate Hox genes? BioEssays. 2008;30:110–121. doi: 10.1002/bies.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshitz HD, Peattie DA, Hogness DS. Novel transcripts from the Ultrabithorax domain of the bithorax complex. Genes Dev. 1987;1:307–322. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Chu WM, Choudary PV, Schmid CW. Cell stress and translational inhibitors transiently increase the abundance of mammalian SINE transcripts. Nucl Acids Res. 1995;23:1758–1765. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.10.1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubbert M. Gene silencing of the p15/INK4B cell-cycle inhibitor by hypermethylation: an early or later epigenetic alteration in myelodysplastic syndromes? Leukemia. 2003;17:1762–1764. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini-Dinardo D, Steele SJ, Levorse JM, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM. Elongation of the Kcnq1ot1 transcript is required for genomic imprinting of neighboring genes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1268–1282. doi: 10.1101/gad.1416906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariner PD, Walters RD, Espinoza CA, Drullinger LF, Wagner SD, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. Human Alu RNA is a modular transacting repressor of mRNA transcription during heat shock. Mol Cell. 2008;29:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martianov I, Ramadass A, Barros A. Serra, Chow N, Akoulitchev A. Repression of the human dihydrofolate reductase gene by a non-coding interfering transcript. Nature. 2007;445:666–670. doi: 10.1038/nature05519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer C, Schmitz KM, Li J, Grummt I, Santoro R. Intergenic transcripts regulate the epigenetic state of rRNA genes. Mol Cell. 2006;22:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, O’Malley BW. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell. 2002;108:465–474. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller VH. Initiation of dosage compensation in Drosophila embryos depends on expression of the roX RNAs. Mech Dev. 2003;120:759–767. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller VH, Rattner BP. The roX genes encode redundant male-specific lethal transcripts required for targeting of the MSL complex. EMBO J. 2002;21:1084–1091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels AA, et al. Binding of the 7SK snRNA turns the HEXIM1 protein into a P-TEFb (CDK9/cyclin T) inhibitor. EMBO J. 2004;23:2608–2619. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney RA, Darst SA, Landick R. Sigma and RNA polymerase: an on-again, off-again relationship? Mol Cell. 2005;20:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI. Regulation of the heat shock transcriptional response: cross talk between a family of heat shock factors, molecular chaperones, and negative regulators. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3788–3796. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VT, Kiss T, Michels AA, Bensaude O. 7SK small nuclear RNA binds to and inhibits the activity of CDK9/cyclin T complexes. Nature. 2001;414:322–325. doi: 10.1038/35104581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobori T, Miura K, Wu DJ, Lois A, Takabayashi K, Carson DA. Deletions of the cyclin-dependent kinase-4 inhibitor gene in multiple human cancers. Nature. 1994;368:753–756. doi: 10.1038/368753a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa Y, Sun BK, Lee JT. Intersection of the RNA interference and X-inactivation pathways. Science. 2008;320:1336–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.1157676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panganiban G, Rubenstein JL. Developmental functions of the Distal-less/Dlx homeobox genes. Development. 2002;129:4371–4386. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauler FM, Koerner MV, Barlow DP. Silencing by imprinted noncoding RNAs: is transcription the answer? Trends Genet. 2007;23:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterlin BM, Price DH. Controlling the elongation phase of transcription with P-TEFb. Mol Cell. 2006;23:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruk S, Sedkov Y, Riley KM, Hodgson J, Schweisguth F, Hirose S, Jaynes JB, Brock HW, Mazo A. Transcription of bxd noncoding RNAs promoted by trithorax represses Ubx in cis by transcriptional interference. Cell. 2006;127:1209–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pheasant M, Mattick JS. Raising the estimate of functional human sequences. Genome Res. 2007;17:1245–1253. doi: 10.1101/gr.6406307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plath K, Fang J, Mlynarczyk-Evans SK, Cao R, Worringer KA, Wang H, de la Cruz CC, Otte AP, Panning B, Zhang Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in X inactivation. Science. 2003;300:131–135. doi: 10.1126/science.1084274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plath K, Mlynarczyk-Evans S, Nusinow DA, Panning B. Xist RNA and the mechanism of X chromosome inactivation. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:233–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.042902.092433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanth KV, Spector DL. Eukaryotic regulatory RNAs: an answer to the ‘genome complexity’ conundrum. Genes Dev. 2007;21:11–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.1484207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner R, Ben-Asouli Y, Krilovetzky I, Jarrous N. A role for the catalytic ribonucleoprotein RNase P in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1621–1635. doi: 10.1101/gad.386706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinn JL, et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo H, Cavaille J. Non-coding RNAs in imprinted gene clusters. Biol Cell. 2008;100:149–166. doi: 10.1042/BC20070126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Elsner T, Gou D, Kremmer E, Sauer F. Noncoding RNAs of trithorax response elements recruit Drosophila Ash1 to Ultrabithorax. Science. 2006;311:1118–1123. doi: 10.1126/science.1117705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro R. The silence of the ribosomal RNA genes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2067–2079. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JV, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM. Enhancer competition between H19 and Igf2 does not mediate their imprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9733–9738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder S, Smits G, Fraser P, Reik W, Paro R. Non-coding transcripts in the H19 imprinting control region mediate gene silencing in transgenic Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:1068–1073. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa L, Breiling A, Lavorgna G, Silvestri L, Casari G, Orlando V. Noncoding RNA synthesis and loss of Polycomb group repression accompanies the colinear activation of the human HOXA cluster. RNA. 2007;13:223–239. doi: 10.1261/rna.266707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamovsky I, Ivannikov M, Kandel ES, Gershon D, Nudler E. RNA-mediated response to heat shock in mammalian cells. Nature. 2006;440:556–560. doi: 10.1038/nature04518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Downes M, Xie W, Kao HY, Ordentlich P, Tsai CC, Hon M, Evans RM. Sharp, an inducible cofactor that integrates nuclear receptor repression and activation. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1140–1151. doi: 10.1101/gad.871201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilatifard A. Chromatin modifications by methylation and ubiquitination: implications in the regulation of gene expression. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:243–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JY, Fitzpatrick GV, Higgins MJ. Two distinct mechanisms of silencing by the KvDMR1 imprinting control region. EMBO J. 2008;27:168–178. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J, Mak W, Zvetkova I, Appanah R, Nesterova TB, Webster Z, Peters AH, Jenuwein T, Otte AP, Brockdorff N. Establishment of histone h3 methylation on the inactive X chromosome requires transient recruitment of Eed-Enx1 polycomb group complexes. Dev Cell. 2003;4:481–495. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutels F, Zwart R, Barlow DP. The non-coding Air RNA is required for silencing autosomal imprinted genes. Nature. 2002;415:810–813. doi: 10.1038/415810a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner DE, Berger SL. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:435–459. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.435-459.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckenholz C, Meller VH, Kuroda MI. Functional redundancy within roX1, a noncoding RNA involved in dosage compensation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2003;164:1003–1014. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.3.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MC, Chiang CM. The general transcription machinery and general cofactors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;41:105–178. doi: 10.1080/10409230600648736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotochaud AE, Wassarman KM. A highly conserved 6S RNA structure is required for regulation of transcription. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:313–319. doi: 10.1038/nsmb917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona RI, Mann MR, Bartolomei MS. Genomic imprinting: intricacies of epigenetic regulation in clusters. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:237–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.092717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voellmy R. On mechanisms that control heat shock transcription factor activity in metazoan cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:122–133. doi: 10.1379/CSC-14R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J, Wagner EG. Target identification of small noncoding RNAs in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Arai S, Song X, Reichart D, Du K, Pascual G, Tempst P, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK, Kurokawa R. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman KM, Saecker RM. Synthesis-mediated release of a small RNA inhibitor of RNA polymerase. Science. 2006;314:1601–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1134830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman KM, Storz G. 6S RNA regulates E. coli RNA polymerase activity. Cell. 2000;101:613–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80873-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenegger M. The role of the RNAi machinery in heterochromatin formation. Cell. 2005;122:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, et al. A subfamily of RNA-binding DEAD-box proteins acts as an estrogen receptor alpha coactivator through the N-terminal activation domain (AF-1) with an RNA coactivator, SRA. EMBO J. 2001;20:1341–1352. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Workman JL. Nucleosome displacement in transcription. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2009–2017. doi: 10.1101/gad.1435706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutz A, Rasmussen TP, Jaenisch R. Chromosomal silencing and localization are mediated by different domains of Xist RNA. Nat Genet. 2002;30:167–174. doi: 10.1038/ng820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Scott F, Fierke CA, Engelke DR. Eukaryotic ribonuclease P: a plurality of ribonucleoprotein enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:165–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Zhu Q, Luo K, Zhou Q. The 7SK small nuclear RNA inhibits the CDK9/cyclin T1 kinase to control transcription. Nature. 2001;414:317–322. doi: 10.1038/35104575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yik JH, Chen R, Nishimura R, Jennings JL, Link AJ, Zhou Q. Inhibition of P-TEFb (CDK9/Cyclin T) kinase and RNA polymerase II transcription by the coordinated actions of HEXIM1 and 7SK snRNA. Mol Cell. 2003;12:971–982. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Gius D, Onyango P, Muldoon-Jacobs K, Karp J, Feinberg AP, Cui H. Epigenetic silencing of tumour suppressor gene p15 by its antisense RNA. Nature. 2008;451:202–206. doi: 10.1038/nature06468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Patton JR, Ghosh SK, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Shen L, Spanjaard RA. Pus3p- and Pus1p-dependent pseudouridylation of steroid receptor RNA activator controls a functional switch that regulates nuclear receptor signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:686–699. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Patton JR, Davis SL, Florence B, Ames SJ, Spanjaard RA. Regulation of nuclear receptor activity by a pseudouridine synthase through posttranscriptional modification of steroid receptor RNA activator. Mol Cell. 2004;15:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart R, Sleutels F, Wutz A, Schinkel AH, Barlow DP. Bidirectional action of the Igf2r imprint control element on upstream and downstream imprinted genes. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2361–2366. doi: 10.1101/gad.206201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]