Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the association between the timing and speed of transition among major smoking milestones (onset, weekly and daily smoking) and onset and recovery from nicotine dependence.

Method

Analyses are based on data from The National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R), a nationally representative face-to-face household survey conducted between February 2001 and April 2003.

Results

Of those who had ever smoked (n=5,692), 71.3% had reached weekly smoking levels and 67.5% had reached daily smoking. Four in ten who had ever smoked met criteria for nicotine dependence. A shorter time since the onset of weekly and daily smoking was associated with a transition to both daily smoking and nicotine dependence, respectively. The risk for each smoking transition was highest within the year following the onset of the preceding milestone. Recovery was associated with a longer period of time between smoking initiation and the development of dependence and a later age of smoking onset.

Conclusions

These findings shed light on the clinical course of smoking and nicotine dependence. Given the importance of timing of smoking transitions, prevalence may be further reduced through intervention targeted at adolescents and young adults in the months most proximal to smoking initiation.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States and is responsible for $157 billion in annual health-related economic losses (1). Further, nicotine dependence, believed to be an important contributor to failed cessation efforts, has been shown to predict future smoking behavior above and beyond smoking quantity (2) and to increase the likelihood of relapse following quit attempts (for review see (3). Traditional accounts of the natural history of smoking have suggested that nicotine dependence follows a series of necessary milestones such as smoking initiation, weekly and daily use (4). While smoking a first cigarette takes place almost exclusively prior to age 18 (5), risk for further experiences with smoking and the opportunity for more significant exposure continues throughout young adulthood. Based on prospective assessment from the Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth (DANDY) study, symptoms of nicotine dependence have been found to emerge in some people before the establishment of daily smoking patterns (6). Reports from the McGill Study on the Natural History of Nicotine Dependence in Teens (NDIT) have confirmed the emergence of dependence symptoms even among non-daily smokers (7, 8). Further, findings from the original National Comorbidity Survey have established continued risk for the transition to a diagnosis for nicotine dependence over a decade following the onset of daily smoking (5).

To date, smoking intervention has been overwhelmingly focused on either prevention of smoking initiation or alternately, treatment for heavy dependent use. Estimating the timing and speed among smoking milestones and their association with the development of nicotine dependence and persistence of smoking behavior is an important challenge for epidemiology given that further reductions in smoking prevalence may be best achieved by programs that target potentially malleable smoking behavior during this uptake process. Notably, however, with the exception of an early age of smoking initiation, which has been linked to increased likelihood of daily smoking and nicotine dependence (9), little else is known about the role of timing and speed of transitions for attaining major smoking milestones across the life course.

While a frequent criticism of cross-sectional research concerns the fact that respondents report past events as having occurred closer to the time of interview than is accurate, these ‘forward telescoping’ errors (Johnson & Schultz, 2005) also occur for the initial interviews of longitudinal investigations when assessing the lifetime prevalence of behavior and cannot be fully eliminated by subsequent waves. Moreover, prospective investigations can establish the order of onset of smoking milestones with certainty, but this benefit applies only to cases where the milestones are identified at different assessment waves (e.g. Insensee et al., 2003), which may be the exception particularly when assessments are spaced by one or more years. While longitudinal investigations are considered ideal for mapping the natural history of behavior, cross-sectional studies also possess a number of strengths that make them one appropriate mode of inquiry into timing and order of onset of both symptoms and behavior. First, their increased feasibility typically leads to larger samples sizes with often broader ranges of key sociodemographic characteristics such as age, education, race and economic status. Second, the findings of large cross-sectional samples are more generalizable to the population than longitudinal investigations that may be geographically restricted and suffer from nonrandom attrition. For these reasons, cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations are complimentary with different respective benefits.

Recent cross-sectional data collected by the National Comorbidity Survey — Replication (NCS-R) allows an evaluation of the association between the timing and speed of transition among major smoking milestones and onset and recovery from nicotine dependence. Specifically, we estimate: 1) the occurrence of nicotine dependence following the achievement of previous smoking milestones (onset, weekly and daily smoking); 2) the influence of timing and speed of transitions between smoking milestones on risk for regular smoking and nicotine dependence; and 3) the association between timing and speed of transitions among smoking milestones and recovery from nicotine dependence. The goal is to provide a first look at these associations in a nationally representative cross sectional sample, that may be tested in future longitudinal research.

Method

Participants and Study Procedures

As described in more detail elsewhere (10), the NCS-R is a nationally representative household survey of English speakers 18 years and older in the contiguous United States. Respondents were selected from a multistage clustered area probability sample of households and face-to-face interviews were carried out between February 2001 and April 2003. The response rate was 70.9%. The NCS-R recruitment, consent, and field procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of both Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

Measures

Diagnostic Assessment

Lifetime smoking behavior and DSM-IV nicotine dependence were based on responses to the WMH-CIDI (11), a fully structured lay interview. Administration of the smoking module included the Part 2 sample and was based on a screening question that inquired whether the respondent had “ever smoked a cigarette, cigar or pipe, even a single puff”. Positive responses to this question were followed with a detailed assessment of lifetime smoking behavior including onset of ever, weekly and daily smoking. Respondents who reported reaching weekly smoking were asked about the DSM-IV symptoms of nicotine dependence (i.e. tolerance, withdrawal or smoking to avoid or reduce withdrawal, smoking in larger amounts or longer than intended, persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down, great deal of time spent to obtain, use or recover from smoking, activities given up or reduced, and smoking despite physical or psychological problems caused or exacerbated by smoking). Those meeting DSM-IV criteria at any point in their lifetime were considered to be nicotine dependent.

Transition Variables

Timing of transitions was based on reported age of onset of smoking initiation (“How old were you the very first time you smoked even a puff of a cigarette, cigar or pipe?), weekly smoking (“How old were you the very first time you smoked tobacco at least once a week for at least two months?”), daily smoking (“How old were you the very first time you smoked tobacco every day, or nearly every day for a period of at least two months?”) and nicotine dependence (“How old were you the very first time you had any of these problems?”). Variables accounting for speed of transitions between smoking milestones were created by subtracting age at reaching an earlier smoking milestone (e.g. smoking initiation) from age at reaching a later milestone (e.g. weekly smoking). Recovery from nicotine dependence was evaluated in terms of the last time that nicotine dependence symptoms were experienced (“How old were you the last time you had any of these problems?”).

Sociodemographic Correlates

Sociodemographic correlates include gender, cohort (defined by age at interview in categories 18-29 years, 30-44 years, 45-59 years, and 60 years), sex, race-ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, other and non-Hispanic white), completed years of education (student status, 0-11 years, 12 years, 13-15 years, and 16 years), and marital status (never married, previously married, and married or cohabitating,).

Data Analytic Procedure

Cumulative incidence curves of ever, weekly and daily smoking and the transition to nicotine dependence were obtained by means of the actuarial method implemented in PROC LIFETEST in SAS, version 9.1.3. The associations between timing and speed of movement through smoking milestones were estimated in discrete-time multivariate logistic regression analyses with person-year as the unit of analysis. Standard errors and significant tests were estimated using the Taylor series linearization method implemented in SUDAAN to adjust for design effects. The person-year variable was defined as the number of years since the onset of the earlier tobacco milestone up to either age of onset of later smoking milestone or age at interview (for censored cases). When predicting recovery from nicotine dependence (i.e. age at which nicotine dependence symptoms were reported as last experienced), the person-year variable was defined as the number of years since the onset of nicotine dependence up to either age of recovery of dependence or age at interview (for censored cases). Additional covariates include gender, cohort, race-ethnicity, education and marital status.

Results

Prevalence of Smoking and Nicotine Dependence

Seventy-three percent (SE 1.2) of the sample (n=5692) reported smoking a puff or more in their lifetime. Of those who had ever smoked, 71.3%, (SE 1.5) had reached weekly smoking levels and 67.5%, (SE 1.5) had reached daily smoking. Four in ten of those who had ever smoked (40.2%, SE 1.0) met criteria for nicotine dependence (population prevalence=29.6%, SE 0.8), with the majority of participants who met criteria for nicotine dependence having reached daily smoking levels (93.5%, SE 0.8) at or before the onset of dependence. Among those who reported reaching daily smoking (population prevalence=49.7%, SE 1.2), 59.5% (SE 1.4) met criteria for nicotine dependence.

Timing and Speed of Smoking Transitions

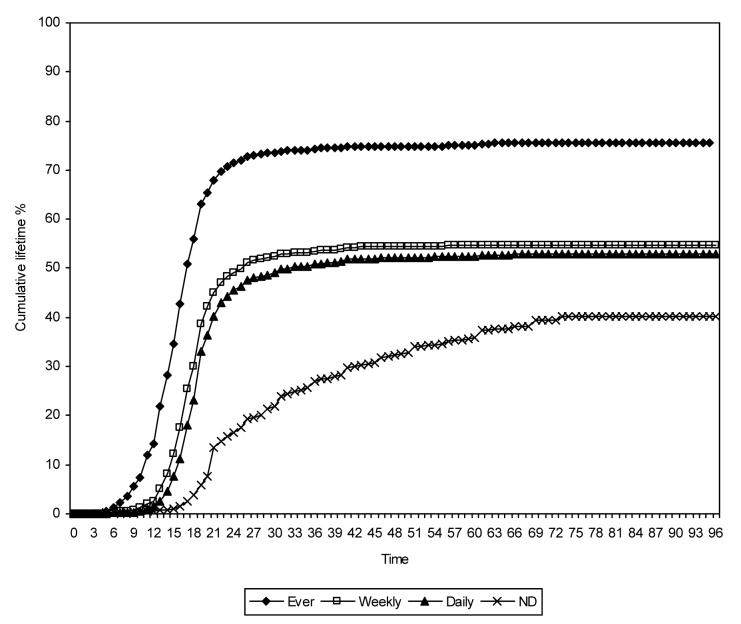

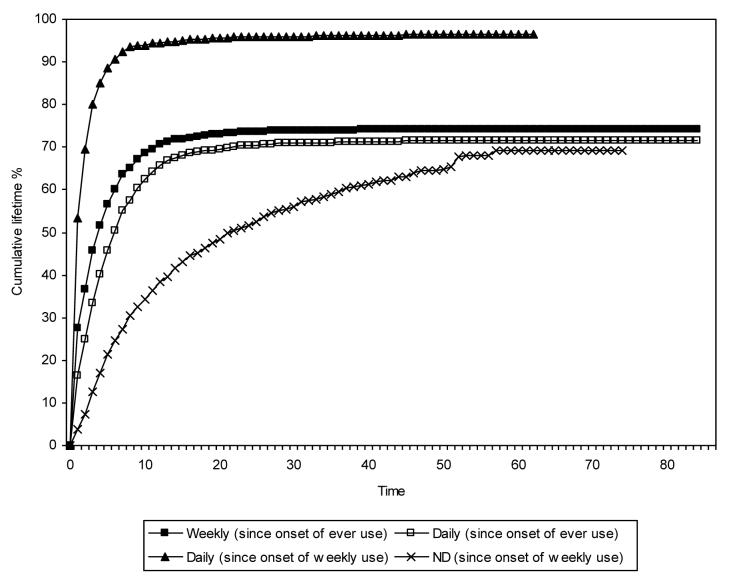

Figure 1 presents the cumulative incidence curves of the transition to each smoking milestone according to chronological age. Except for the curve for nicotine dependence which shows its steepest acceleration between 18 and 21 and continues to increase for several years, the cumulative probability of attaining the remaining smoking milestone shows the sharpest increase beginning at age 12 and leveling off by age 20. Fig. 2 depicts the cumulative probability of attaining each smoking milestone according to time from achievement of a previous milestone. The cumulative probability of weekly and daily smoking increased sharply during the first 5 years following smoking initiation; the rate of increase is slower to 10 years and levels off thereafter. More than half of the conversion to daily smoking occurred in the first year following the onset of weekly smoking with increases in cumulative probability continuing to 5 years. In contrast, the cumulative probability of nicotine dependence shows its sharpest increase in the first 10 years following weekly smoking followed by a slower rate of increase continuing for several years.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence curves of ever, weekly, daily smoking and nicotine dependence in the National Comorbidity Survey - Replication (time=chronological age).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence curves of ever, weekly, daily smoking and nicotine dependence in the National Comorbidity Survey - Replication (time=years since onset of previous smoking milestone).

Timing and Speed of Transitions Predicting Smoking Milestones

After controlling for gender, cohort, race-ethnicity, education and marital status, discrete-time multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that a shorter time since smoking initiation significantly predicted the transition to weekly smoking among ever smokers, OR 0.82 (0.80-0.84). Specifically, the transition to weekly smoking was significantly more likely to occur in the same year as smoking onset than in any other period following smoking initiation. When predicting daily smoking, those reporting a faster transition between initiation and weekly use were more likely to reach daily smoking levels, OR 0.97 (0.95-0.99). Further, a shorter time since the onset of weekly smoking was associated with a transition to daily smoking, OR 0.77 (0.74-0.80). Again, the transition to daily smoking was significantly more likely to occur in the same year as the onset of weekly smoking compared to a year or more following the weekly smoking transition. When predicting nicotine dependence among those who had reached at least weekly smoking levels, an earlier age of smoking initiation, OR 0.94 (0.90-0.99), and a faster transition between smoking initiation and daily smoking, OR 0.96 (0.94-0.99), predicted a transition to nicotine dependence. While the transition to nicotine dependence was more likely to occur in the same year as the onset of weekly smoking compared to 6 or more years past the onset of weekly smoking, dependence was similarly likely to onset across the first 5 years following the achievement of daily smoking.

Timing and Speed of Transition Predicting Recovery from Nicotine Dependence

The speed and timing of transitions were also examined in relation to recovery from nicotine dependence. Recovery increased with every additional year following the onset of nicotine dependence, OR 1.02 (1.01-1.03), and with every additional year between the first use of tobacco and the onset of dependence, OR 1.05 (1.04-1.06). That is, developing nicotine dependence in the more distant past and with a longer interval between smoking initiation and nicotine dependence are associated with a higher incidence of recovery. A later age of smoking onset was also independently associated with recovery from nicotine dependence, OR 1.05 (1.02-1.07).

Discussion

This investigation documented the natural course of tobacco use across four major milestones: initiation, weekly smoking, daily smoking and nicotine dependence. Key findings showed that nearly three-quarters of the population reported smoking a puff or more in their lifetime. Of those who had ever smoked, 71.3% had reached weekly smoking levels and 67.5% had reached daily smoking. Four in ten of those who had ever smoked met criteria for nicotine dependence with most participants reaching daily smoking levels at or before the onset of nicotine dependence. A faster transition between previous smoking milestones was associated with the progression to both daily smoking and nicotine dependence and the risk for each smoking transition was highest within the year following the onset of the preceding milestone. Recovery from nicotine dependence was, by contrast, associated with a slower transition between initiation and the onset of dependence, a later age of smoking initiation and an increased number of years following the onset of nicotine dependence.

Overall, rates of ever smoking (12), and daily smoking (5, 12) reported herein, mirror those described in previous studies based on nationally representative samples of adults. The rate of DSM-IV nicotine dependence however, was found to be somewhat higher in the present NCSR sample (29.6%, 0.8) compared to the National Epidemiologic Study of Alcohol and Related Conditions (17.7%, 0.23), the only other representative survey of U.S. adults to establish prevalence based on formal DSM-IV criteria. This discrepancy may be based on the different threshold of use required for the administration of nicotine dependence symptoms in the NESARC (i.e. one of the following: 100+ cigarettes, Pipe, 50+ times, snuff, 20+ times, chewing tobacco, 20+ times) compared to the weekly use for a month or more threshold used by NCS-R (Grant, Hasin, Chou, Stinson, & Dawson, 2004).

The present study advanced knowledge by demonstrating the effects of both speed and timing of transitions on the achievement of major smoking milestones. Individuals who initiate smoking at a younger age have been previously shown to be at increased risk for developing nicotine dependence and chronic smoking (13, 14). While we confirmed this with regard to nicotine dependence, with increased risk among initiating earlier, age of initiation was not found to be associated with the transitions to either weekly or daily use. Instead, it was the time since the previous milestone that most consistently predicted each smoking outcome. In each case, achievement of a higher smoking milestone was most common in the year or years most proximal to the onset of the preceding milestone. The transition to weekly use was most likely to occur during the year when smoking was first initiated. The same was true for transitions to daily smoking in which onset was most common in the year when weekly smoking levels were first established.

The speed of transition between initiation and weekly use and between initiation and daily use were also found to be associated with daily smoking and nicotine dependence, respectively. The fact that timing between these previous smoking milestones was independently associated with the transition to daily smoking and nicotine dependence further confirms the importance of this early clinical course in establishing who will become a chronic smoker. In some respects, the findings regarding speed of transition may also partially contradict common theories of dependence which emphasize heavy exposure as the primary influence in the development of addiction. That is, given that a subgroup of smokers report developing nicotine dependence before the onset of daily smoking and that among those who reach daily smoking before dependence, onset of nicotine dependence was often rapid, it is likely that other factors beyond heaviness of exposure is driving this progression, a conception that has been supported in previous research (6, 7).

In terms of recovery, we again demonstrated the importance of the early course of smoking exposure. Among those who had met criteria for nicotine dependence, both speed and timing of past smoking transitions were found to predict recovery from nicotine dependence. Although the link between age of smoking onset and both smoking persistence and failed attempts at smoking cessation have been widely reported (15-17) the present study is the first to document the added risk that speed and transition timing may have on the chronicity of nicotine dependence showing that likelihood of recovery is increased with longer periods of transition between the first use of tobacco and the onset of dependence.

The present findings should also be considered within the context of study limitations. Retrospective reporting of age of reaching smoking milestones is subject to error, given that respondents are being asked about events that, for older persons, may have occurred decades ago. Also, given the cross-sectional nature of our data and the measurement of dependence symptom onset in reference to those who reached full criteria for DSM-IV nicotine dependence, the present study may not be wholly comparable to previous prospective work which has often focused on the earliest stages of dependence symptoms among novice smokers (18, 19). This research does however add to this accumulating evidence that for many, smoking initiation represents the beginning of a process that leads rapidly to established smoking and nicotine dependence. Therefore, more targeted intervention aimed at adolescents and young adults based on their previous exposure to smoking may be warranted. Currently, the malleability of smoking behavior during this uptake process is unknown, but may represent an appropriate point of intervention. Additional longitudinal work focused the timing and speed of smoking transitions is now required.

Acknowledgements

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) was supported by grant U01-MH60220 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; grant 044708 from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the John W. Alden Trust. Data analyses and manuscript preparation were undertaken with support from an Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (Jianping, Kalaydjian, Merikangas), grant K01 DA15454 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (Dierker); an Investigator Award from the Patrick & Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation (Dierker) and support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Tobacco Etiology Research Network.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the U.S. government.

References

- 1.CDC Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs--United States, 1995-1999 Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report. 2002. pp. 3003–3003. [PubMed]

- 2.Sledjeski E, Dierker L, Costello D, Shiffman S, Donny E, Flay BR. Predictive validity of four nicotine dependence measures in a college sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;87:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker T, Japuntich SJ, Hogel JM, McCarthy DE, Curtain JJ. Pharmacologic and Behavioral withdrawal from addictive drugs. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(5):232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 4.SAMHSA: Office of Applied Studies National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2002 http://www.samhsa.gov/oas/nhsda.htm.

- 5.Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hiripi E, Kessler R. Nicotine dependence in the United States: prevalence, trends, and smoking persistence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:810–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, Coleman M, Wood C. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: The DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(4):397–403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gervais A, O’Loughlin J, Meshefedjian G. Milestones in the natural course of onset of cigarette use among adolescents. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;175(3) doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF, Meshefedjian G, McMillan-Davey E, Clarke P, Hanley J, Paradis G. Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron-Epel O, Haviv-Messika A. Factors associated with age of smoking initiation in adult populations from different ethnic backgrounds. European Journal of Public Health. 2004;14(3):301–305. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): Background and aims. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(2):60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mei-Chen Hu MD, Kandel Denise B. Epidemiology and Correlates of Daily Smoking and Nicotine Dependence Among Young Adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(2):299–309. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett S, Husten C, Kann L, Warren C, Sharp D, Crosset L. Smoking initiation and smoking patterns among US college students. Journal of American College Health. 1999;48:55–60. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everett S, Warren C, Sharp D, Kann L, Husten C, Crossett L. Initiation of cigarette smoking and subsequent smoking behavior among U.S. high school students. Preventive Medicine. 1999;29(5):327–333. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Determining the probability of future smoking among adolescents. Addiction. 2001;96(2):313–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96231315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilpin EA, White VM, Pierce JP. What fraction of young adults are at risk for future smoking, and who are they? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7(5):747–759. doi: 10.1080/14622200500259796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslau N. Daily cigarette consumption in early adulthood: Age of smoking initiation and duration of smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1993;33(3):287–291. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiFranza JR, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, Ockene JK, Savageau JA, Cyr D, Coleman M. Initial symptoms of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Tobacco Control. 2000;9(3):313–319. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karp I, O’Loughlin J, Paradis G, Hanley J, DiFranza J. Smoking trajectories of adolescent novice smokers in a longitudinal study of tobacco use. Annuls of Epidemiology. 2005;15(6):445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]