Abstract

Objective To compare the clinical effectiveness of larval therapy with a standard debridement technique (hydrogel) for sloughy or necrotic leg ulcers.

Design Pragmatic, three armed randomised controlled trial.

Setting Community nurse led services, hospital wards, and hospital outpatient leg ulcer clinics in urban and rural settings, United Kingdom.

Participants 267 patients with at least one venous or mixed venous and arterial ulcer with at least 25% coverage of slough or necrotic tissue, and an ankle brachial pressure index of 0.6 or more.

Interventions Loose larvae, bagged larvae, and hydrogel.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was time to healing of the largest eligible ulcer. Secondary outcomes were time to debridement, health related quality of life (SF-12), bacterial load, presence of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus, adverse events, and ulcer related pain (visual analogue scale, from 0 mm for no pain to 150 mm for worst pain imaginable).

Results Time to healing was not significantly different between the loose or bagged larvae group and the hydrogel group (hazard ratio for healing using larvae v hydrogel 1.13, 95% confidence interval 0.76 to 1.68; P=0.54). Larval therapy significantly reduced the time to debridement (2.31, 1.65 to 3.2; P<0.001). Health related quality of life and change in bacterial load over time were not significantly different between the groups. 6.7% of participants had MRSA at baseline. No difference was found between larval therapy and hydrogel in their ability to eradicate MRSA by the end of the debridement phase (75% (9/12) v 50% (3/6); P=0.34), although this comparison was underpowered. Mean ulcer related pain scores were higher in either larvae group compared with hydrogel (mean difference in pain score: loose larvae v hydrogel 46.74 (95% confidence interval 32.44 to 61.04), P<0.001; bagged larvae v hydrogel 38.58 (23.46 to 53.70), P<0.001).

Conclusions Larval therapy did not improve the rate of healing of sloughy or necrotic leg ulcers or reduce bacterial load compared with hydrogel but did significantly reduce the time to debridement and increase ulcer pain.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN55114812 and National Research Register N0484123692.

Introduction

Venous leg ulcers develop from underlying venous disease and are one of the most common chronic wound types.1 High compression bandaging is effective but only about 50% of leg ulcers are healed within 16 weeks, leaving scope for further improvements.2 3 4

An important aspect of wound management is thought to be removal of devitalised tissue from the surface of the ulcer; a process called debridement.5 6 It has been suggested that larval therapy debrides wounds more swiftly than standard treatments7 8 as well as stimulating healing,9 10 11 12 reducing bacterial load,13 14 15 16 17 and eradicating meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus.18 Larvae used for medicinal purposes are available in loose and bagged formulations. Although larval therapy is increasingly used it has been evaluated in just one published randomised controlled trial, which included only 12 patients with venous leg ulcers and reported debridement rather than healing as the surrogate outcome.19 Evidence for any antimicrobial activity with use of larvae comes mainly from laboratory studies.14 15 16

We undertook a randomised controlled trial to evaluate the clinical and cost effectiveness of larval therapy compared with a standard debridement treatment (hydrogel) on time to complete healing of leg ulcers, time to debridement, cost of treatments, health related quality of life (including ulcer pain), and microbiology. The economic evaluation is reported in the accompanying paper.20

Methods

This was a pragmatic multicentre, randomised, open trial with equal randomisation, carried out in 22 centres in the United Kingdom from July 2004 to May 2007.

Participants were recruited from leg ulcer clinics, community nurse caseloads, hospital wards, and hospital outpatient departments (for example, dermatology or surgery). Participants gave written informed consent. Eligible participants had venous or mixed venous and arterial leg ulcers (assessed as an ankle brachial pressure index ≥0.6) with at least 25% of the wound covered by slough or necrotic tissue (larval therapy would not normally be used on wounds with less coverage). We considered ulcers with an area of 5 cm2 or less as eligible if they were non-healing (defined as no change in area over the preceding month). If a patient had multiple ulcers we chose the largest eligible ulcer as the reference lesion. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or lactating, were allergic to hydrogel, had grossly oedematous legs, or were taking anticoagulants (contraindicated with larval therapy).

After consenting to the trial, participants were randomised to receive either loose larvae (Zoobiotic; Bridgend, Wales), bagged larvae (Biomonde; Barsbüttel, Germany), or hydrogel (Purilon; Coloplast, Denmark), with nurses using a remote, telephone randomisation service provided by York Trials Unit (allocation was therefore fully concealed). Randomisation was done using permuted blocks with stratification by trial centre and ulcer area (≤5 cm2 or >5 cm2). A computer programmer, who was not involved in the data analysis, created the randomisation program using randomly permuted blocks with block sizes of three and six.

Interventions

Nurses were encouraged to consider all participants for compression and to use four layer bandaging 4 unless contraindicated by ankle brachial pressure index or patient tolerance.

We used sterile Lucilia sericata larvae. The number of larvae required for each application was determined from manufacturers’ guides. Larvae were left on the ulcer for three or four days, and nurses could assess the participant during this period. Participants could not receive compression bandaging while larvae were in situ. If further larval therapy was required on removal of the dressing, hydrogel and the participant’s usual bandage were applied while more larvae were ordered.

Participants in the control group received hydrogel covered with a knitted viscose dressing as well as compression depending on the ankle brachial pressure index and patient tolerance. Frequency of application was decided by the treating nurse.

The randomised treatment was applied in the debridement phase: this ended either when debridement occurred or when treatment was stopped before debridement (classified as withdrawal from trial treatment). In the phase after debridement, participants received a standard knitted viscose dressing with or without compression. The maximum length of follow-up was 12 months, although some participants who were randomised towards the end of recruitment had follow-up of between six and 12 months. We stopped collecting routine clinical data for participants whose reference ulcer had healed but asked them to continue completing questionnaires on quality of life and use of resources.

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome was time to complete healing of the reference ulcer. Ulcer healing was defined as complete epithelial cover in the absence of a scab (eschar), which was assessed by the nurse with independent corroboration by another nurse one week later. In the event of disagreement, treatment continued until agreement was reached on healing status. Nurses took digital photographs weekly for six months and then monthly. These were assessed centrally to ascertain healing status by two independent assessors, masked to treatment group.

Secondary outcomes were time to debridement of the ulcer, health related quality of life, microbiology (bacterial load and MRSA), adverse events, and ulcer related pain. Debridement was defined as a cosmetically clean wound. Nurses recorded the date a wound had debrided. Debridement status was also assessed by masked independent assessors using digital photographs. We used the SF-12, previously found to be sensitive to changes in the healing status of venous ulcers,21 to measure participants’ perceptions of health related quality of life both at the baseline assessment and at three, six, nine, and 12 months.

Microbiological swabs were taken at baseline, after removal of each trial debridement treatment during the first month (if the ulcer debrided within one month then weekly until one month), and then monthly until healing or completion of the trial. Laboratory analysis, blind to treatment, measured total bacterial load (10x copies/ml) and the presence or absence of MRSA.

We classed adverse events as serious or non-serious. Some events were always classified as serious (death, life threatening event, admission to hospital, persistent or significant disability or incapacity); the seriousness of other events (for example, infection and deterioration of the wound) was judged by the treating nurse. Health professionals indicated whether or not they believed the event was related to trial treatment. On the basis of reports in the literature and our earlier trial (VenUS I),4 we established a list of possible treatment related adverse events a priori (pressure damage, maceration, excoriation and infection ulcer related pain, ulcer deterioration).

Participants recorded ulcer related pain over the past 24 hours on a visual analogue scale at baseline and at first removal of the debridement treatment. The scale ranged from no pain (0 mm) to worst pain imaginable (150 mm).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were done in SAS version 9.1, and significance testing used a two sided 5% significance level.

We determined that we required 370 participants to detect a reduction in median healing time from 20 to 12.7 weeks with 90% power while allowing for 15% loss to follow up, or 270 participants to detect the same difference with 80% power. The estimated 20 week healing time for the control group and the difference between groups was based on the results of VenUS I.4

We initially compared time to debridement and time to healing between the three treatment groups using a log rank test. These treatment effects were explored in a Cox proportional hazards model including randomisation stratification factors (centre, baseline ulcer area) as well as prognostic variables (duration of ulcer and ulcer type: ankle brachial pressure index ≥0.8 and high compression; ankle brachial pressure index ≥0.8 and lower or no compression; ankle brachial pressure index 0.6 to 0.8). A priori we decided that if we found no evidence of a difference between loose and bagged larvae groups then we would present the hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for larval therapy overall (loose and bagged larvae groups combined) compared with hydrogel. The proportional hazards assumption was checked.

We calculated the physical component summary score and mental component summary score of the SF-12 for each participant and used descriptive statistics to summarise these at each assessment. The standardised areas under the curve (area under the curve22 for each participant adjusted for the duration of available data) were reported for the larvae and hydrogel groups and compared using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Values were compared with those of age specific norms, available for the United States.23

Data on bacterial load were log transformed. We used a repeated measures regression model to compare changes in bacterial load over time between the larvae and hydrogel groups. Time of the ulcer swab was a continuous measure and we included a quadratic term to test if the effects of time were non-linear. We considered treatment (larvae or hydrogel), time, baseline ulcer area, ulcer type, and duration of ulcer as fixed effects and participants as random effects. The interaction between treatment and time was also assessed. We analysed bacterial load to the end of the trial and to the end of the debridement phase.

We used Fisher’s exact test to compare the proportion of participants (positive for MRSA at baseline) with MRSA eradicated by the end of the debridement phase between larvae and hydrogel groups. This was repeated for the proportion of participants who were negative for MRSA at baseline but who tested positive for MRSA at any follow-up assessment.

Using a negative binomial model and adjusting for the same covariates as the primary analyses we compared the numbers of adverse events in each participant between treatment groups. We also compared treatment groups for ulcer related pain during the 24 hours before the first removal of the debridement treatment (measured on a visual analogue scale), using linear regression and adjusting for baseline pain score, ulcer area, duration of ulcer, and ulcer type.

Results

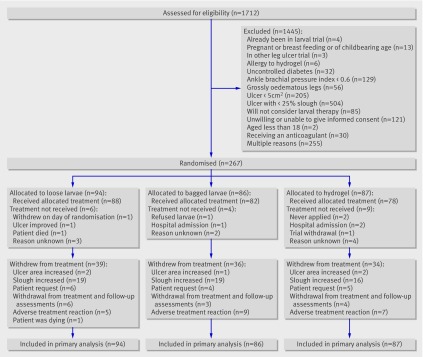

Between July 2004 and May 2007, 1712 people with leg ulcers were screened and 267 (15.6%) randomised from 18 centres: 94 to loose larvae, 86 to bagged larvae, and 87 to hydrogel. The remaining four centres did not recruit participants. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the trial and table 1 summarises their baseline characteristics.

Fig 1 Flow of participants through trial

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with leg ulcer allocated to one of three treatments for debridement: loose larvae, bagged larvae, or hydrogel. Values are numbers (percentages) of participants unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Loose larvae (n=94) | Bagged larvae (n=86) | Hydrogel (n=87) | Overall (n=267) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 36 (38.3) | 29 (33.7) | 44 (50.6) | 109 (40.8) |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 74.1 (12.9) | 73.5 (12.2) | 74.3 (12.8) | 74.0 (12.6) |

| Area of ulcer (cm2): | ||||

| ≤5 | 23 (24.5) | 20 (23.3) | 22 (25.3) | 65 (24.3) |

| >5 | 71 (75.5) | 66 (76.7) | 65 (74.7) | 202 (75.7) |

| Median (range) area of ulcer (cm2)* | 12.2 (0.6-174.9) | 17.3 (1.8-197.9) | 12.2 (1.0-116.8) | 13.2 (0.6-197.9) |

| Duration of ulcer (months): | ||||

| ≤6 | 33 (35.1) | 46 (53.5) | 35 (40.2) | 114 (42.7) |

| >6 | 61 (64.9) | 40 (46.5) | 52 (59.8) | 153 (57.3) |

| Median (range) duration of ulcer (months)* | 9.0 (1.0-240.0) | 6.0 (1.0-204.0) | 8.0 (1.0-372.0) | 7.0 (1.0-372.0) |

| ABPI, treatment: | ||||

| ≥0.8, high compression | 50 (53.2) | 46 (53.5) | 61 (70.1) | 157 (58.8) |

| ≥0.8, lower or no compression | 31 (33.0) | 30 (34.9) | 17 (19.5) | 78 (29.2) |

| 0.6-0.8 | 13 (13.8) | 10 (11.6) | 9 (10.3) | 32 (12.0) |

ABPI=ankle brachial pressure index.

*Median presented as data were skewed.

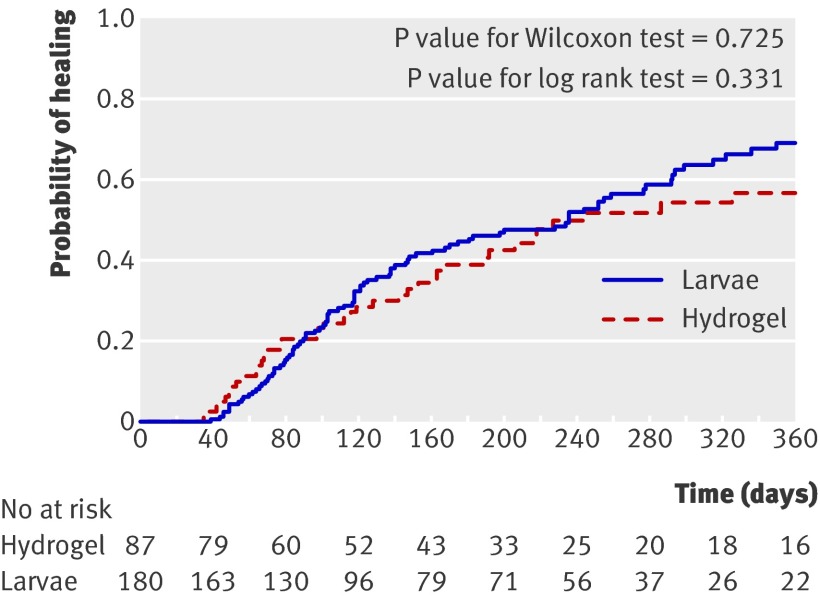

Time to ulcer healing did not differ between the groups (log rank test 1.00, df=2, P=0.62). In the adjusted analysis, healing rates did not differ between the loose and the bagged larvae arms (χ2 0.19, df=1, P=0.66). Results are therefore presented for larvae overall (loose and bagged larvae arms combined) compared with hydrogel. The median time to healing in the larvae group was 236 days (95% confidence interval 147 to 292) and in the hydrogel group was 245 days (166 to upper limit not estimable). Figure 2 shows the Kaplan Meier survival curve for time to healing of ulcers in both groups.

Fig 2 Kaplan Meier plot of time to ulcer healing after larval therapy (loose and bagged larvae arms combined) compared with hydrogel

The hazard ratio from the adjusted analysis for larvae compared with hydrogel was 1.13 (95% confidence interval 0.76 to 1.68, P=0.54), indicating a slightly increased likelihood of healing in the larvae group, although this was not statistically significant. When the analysis was repeated using the date of healing as recorded by the nurses on the patient record forms the conclusions remained the same.

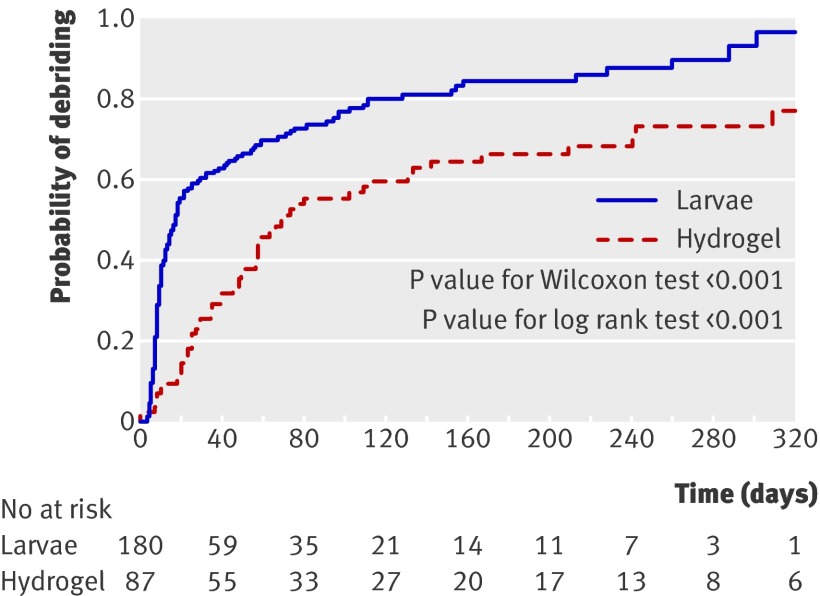

Time to debridement differed significantly between the three groups (25.38, df=2, log rank test P<0.001). The median time to debridement with loose larvae was shorter (14 days, 95% confidence interval 10 to 17) than with bagged larvae (28 days, 13 to 55) and with hydrogel (72 days, 56 to 131). When loose and bagged larvae were compared in the adjusted analysis, however, the difference in time to debridement was not significant (χ2 1.52, df=1, P=0.22). Figure 3 shows the Kaplan Meier curve for time to debridement in both groups.

Fig 3 Kaplan Meier plot of time to debridement of ulcer using larvae (loose and bagged combined) compared with hydrogel

The rate of debridement at any time in either larvae groups was about twice that of the hydrogel group; the hazard ratio for the combined larvae group compared with hydrogel was 2.31 (95% confidence interval 1.65 to 3.24, P<0.001).

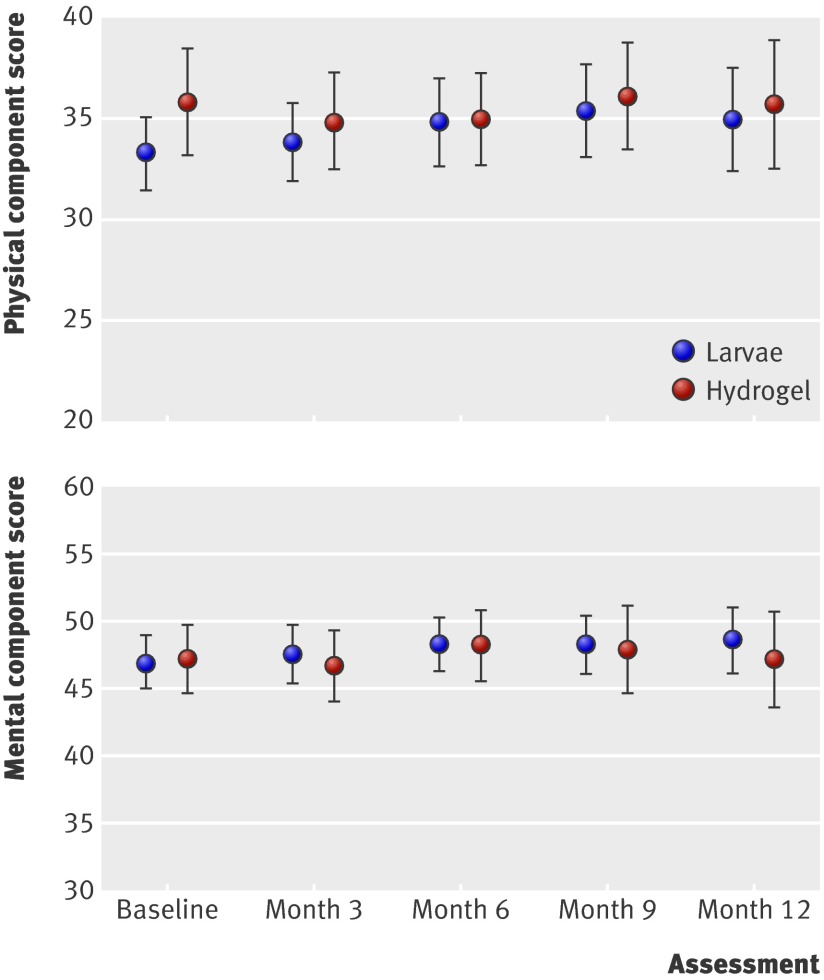

The mean baseline physical component summary score for the combined larvae group was 33.3 (SD 11.4) and for the hydrogel group was 35.9 (SD 11.5). These values were low compared with the 37.9 (SD 11.16) for norm based scores of people aged 75 and over in the US. The mean baseline mental component summary score for the combined larvae group was 46.9 (SD 12.3) and for the hydrogel group was 47.2 (SD 11.0), compared with 50.4 (11.66) for the general US population. The physical component summary scores did not differ between the groups (median area under the curve 0.4. for the combined larvae group, −0.5 for the hydrogel group, P=0.25), indicating no evidence of a difference between the two groups (fig 4). The result for the mental component summary was: median area under the curve −0.8 for the combined larvae group and −0.7 for the hydrogel group (P=0.95, fig 4).

Fig 4 Mean (95% CI) SF-12 physical component and mental component scores over time in patients with leg ulcers treated by larval therapy or hydrogel

The average log bacterial count at baseline was 6.5 (about 3.1×106 copies/ml) and was similar across the groups. The analysis of data collected from swabs during the trial showed no evidence of a difference in bacterial load over time between the combined larvae group and the hydrogel group (difference in means (larvae minus hydrogel) −0.06, 95% confidence interval −0.24 to 0.12, P=0.75). There was evidence that overall ulcer bacterial load decreased over time in both groups (P=0.01) but no evidence that reductions over time were different between the groups (P=0.63). Similar results were seen in the analysis of bacterial load only up to the point of debridement.

The prevalence of MRSA at baseline was low, with only 6.7% of participants (18/267) having a positive swab at baseline: seven participants allocated to loose larvae, five allocated to bagged larvae, and six allocated to hydrogel. Of these, MRSA was eradicated during the debridement phase in 57.1% (4/7) of participants allocated to loose larvae, 100% (5/5) allocated to bagged larvae, and 50% (3/6) allocated to hydrogel. There was no evidence of a difference between the combined larvae and the hydrogel groups (75% (9/12) v 50% (3/6); P=0.34). Also, the number of participants who were negative for MRSA at baseline but positive at one or more follow-up assessments did not differ between the combined larvae and the hydrogel groups (7.1% (12/168) v 2.5% (2/81); Fisher’s exact test P=0.16).

In total, 131 participants had 340 adverse events. Of these, 13.8% were classed as serious, corresponding to 14.6% events with loose larvae, 13.5% with bagged larvae, and 13.5% with hydrogel. More participants in the combined larvae group experienced one or more adverse events than participants in the hydrogel group (51.7% v 43.7%) but this difference was not significant (χ2 2.65, df=1, P=0.10).

The mean ulcer related pain scores (for the 24 hours before removal of first debridement treatment) for the larvae groups were about double those of the hydrogel group (table 2). After adjustment, significantly more pain was experienced by participants in both larvae groups (P<0.001) than in the hydrogel group.

Table 2.

Difference in ulcer related pain score at first removal of treatment (larvae minus hydrogel)

| Variables | Estimate (SE) | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group: | |||

| Loose larvae (n=82): hydrogel (n=71) | 46.74 (7.25) | <0.001 | 32.44. to 61.04 |

| Bagged larvae (n=70): hydrogel (n=71) | 38.58 (7.67) | <0.001 | 23.46 to 53.70 |

| Baseline pain score | 0.41 (0.07) | <0.001 | 0.26 to 0.55 |

| Area (log) | 1.34 (2.94) | 0.65 | −4.41 to 7.10 |

| Duration of ulcer (log) | −4.23 (2.36) | 0.07 | −8.86 to 0.40 |

Bracketed values in first column are numbers of participants.

Discussion

We found no evidence that a phase of treatment with loose or bagged larvae reduces the time to healing of leg ulcers compared with hydrogel. The median healing times (236 days for the larvae groups and 245 days for the hydrogel group) were longer than in our previous trial, where the median time to healing with four layer bandaging was 92 days and with short stretch bandaging was 126 days. The most likely explanation for the increased healing time in the current trial (VenUS II) is that we restricted eligibility to the trial to patients with sloughy and necrotic leg ulcers and ulcers associated with more arterial disease than in the previous study. We also found no evidence of a difference in health related quality of life or bacterial load.

Our findings do, however, indicate that larvae are a more effective debriding agent than hydrogel. This is the first report of pain associated with larval therapy in a large number of patients with leg ulcers, with a control group for comparison. Pain reported in the 24 hours before removal of the first larvae treatment was considered related to the procedure and was probably transient and did not seem to impact on the health related quality of life measurements made at three monthly intervals.

The low rate of MRSA identified in these mainly community dwelling patients with leg ulcers is welcomed and contrasts with previous reports.24 25 We also showed that MRSA can be eradicated from leg ulcers irrespective of whether larval therapy is used.

Strengths and limitations of study

We believe that this is the first randomised controlled trial to investigate the effect of larval therapy on wound healing and we used blinded outcome assessment to protect against observer bias. Although trial evidence is limited, there are several non-randomised controlled trials that led to the promotion of larval therapy as a clinically effective treatment7 26 27 28 29; “effective” variously defined as the promotion of healing,10 11 12 30 31 promotion of debridement,8 reduction in number of micro-organisms in the wound,14 15 16 and reduction of MRSA specifically.16 The present trial provides a more robust evidence base to explore these issues.

As we did not investigate debridement as a longer term outcome we were unaware of how many ulcers that did debride remained debrided. Furthermore, although the current study is the first randomised controlled trial we have identified to investigate and publish data on the antimicrobial action of larval therapy, we also recognise the limitations of the methods used. We only investigated an association between larval therapy and total bacterial load. Beyond identification of MRSA we did not have the resources to carry out qualitative investigation of bacterial flora so can not draw any conclusions about the impact of larval therapy on other species.

Finally, as with many randomised controlled trials, recruitment of sufficient numbers of eligible patients was a challenge and we did not reach our initial sample size despite an extension in time and funding. The reasons for this are probably complex. Anecdotally, nurses thought there were fewer patients with leg ulcers than previously, attributing this to an increased use of compression bandaging. Secondly, fewer ulcers than we originally anticipated were sloughy. Indeed the main single reason for exclusion of patients from the trial was ulcers not containing sufficient slough. Since this is a prerequisite for using larval therapy, our experience suggests that doing a larger trial in the United Kingdom would be challenging.

Possible explanations and implications for clinicians and policymakers

We found no evidence to recommend the routine use of larval therapy on sloughy leg ulcers to speed up healing or reduce bacterial load. If debridement in itself is a goal of treatment, such as before skin grafting or other surgery, then larval therapy should be considered; however, it is associated with significantly more pain than hydrogel. Future treatment decisions should be fully informed by the finding that there is no evidence of an impact on healing time.

Unanswered questions and future research

The present study supports the view that larval therapy is an effective debriding agent. However, the study raises uncertainty about the role of debridement in the care of leg ulcers. Although debridement is viewed as an important part of preparation of the wound bed, data describing the relation between debridement and healing are sparse. Research is required to explore the relation between debridement, healing, and microbiology as well to better understand the value of debridement as an outcome from the patient’s perspective.

What is already known on this topic

Larvae are increasingly used to treat leg ulcers and are thought to stimulate healing, reduce bacterial load, and eradicate MRSA

Clinical evidence to support larval therapy comes from a small randomised controlled trial that did not follow patients to healing

What this study adds

Larval therapy significantly reduced the time to debridement of sloughy or necrotic leg ulcers compared with hydrogel

Larval therapy did not increase healing rates nor reduce bacterial load and was associated with significantly more ulcer related pain in the 24 hours before removal of the first treatment than hydrogel

We thank the participants for taking part in the trial; the research nurses, tissue viability teams, district nurses, and hospital outpatient staff for recruiting participants and completing the trial documentation; the principal investigators at each site for coordinating recruitment of the participants; members of the trial steering committee (Su Mason (independent chair), Mike Campbell, and Francine Cheater); and members of the data monitoring and ethics committee (Keith Abrams (chair), Michelle Briggs, and Alun Davies) for overseeing the study.

The VenUS II collaborators (current and past) are: Una Adderley, Jacqui Ashton, Gill Bennett, JMB, Anne Marie Brown, Sue Collins, Ben Cross, NC, Val Douglas, CD, JCD, Andrea Ellis, Caroline Graham, Christine Hodgson, Gemma Hancock, Shervanthi Homer-Vanniasinkam, CI, June Jones, Nicky Kimpton, Dorothy McCaughan, Elizabeth McGinnis, Jeremy Miles, JLM, Veronica Morton, EAN, Sue O’Meara, Angie Oswald, Emily Petherick, Ann Potter, Pauline Raynor, Linda Russell, Jane Stevens, MS, Nikki Stubbs, DJT, Kath Vowden, Peter Vowden, Michael Walker, Shernaz Walton, Val Wadsworth, Margaret Wallace Judith Watson, Anne Witherow, and GW.

Contributors: JCD was trial manager between 2005 and 2008. GW and JMB designed and carried out the statistical analyses. MS and CI designed and carried out the economic analyses and contributed to the analysis of the trial. CI contributed to the design of the trial. NC was the chief investigator, led the design of the trial, chaired the Trial Management Group, and edited and approved the final draft of the report. She is guarantor. CD advised on the collection and analysis of microbiological data. JLM carried out the microbiological analysis. EAN and DJT contributed to the design and coordination of the study.

Funding: This project was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme (project No 01/41/04). The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health. Zoobiotic supplied and distributed the loose larvae at no cost and Biomonde supplied the bagged larvae at no cost. These manufacturers had no role in the design of the trial or in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the West Midlands multicentre research ethics committee and local ethics committees.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b773

References

- 1.Nelzen O, Bergqvist D, Lindhagen A. Venous and non-venous leg ulcers: clinical history and appearance in a population study. Br J Surg 1994;81:182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullum N, Nelson EA, Flemming K, Sheldon T. Systematic reviews of wound care management: (5) beds; (6) compression; (7) laser therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, electrotherapy and electromagnetic therapy. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullum N, Nelson EA, Fletcher AW, Sheldon TA. Compression for venous leg ulcers [update of Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(3):CD000265]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(2):CD000265. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iglesias C, Nelson EA, Cullum NA, Torgerson DJ, Ven UST. VenUS I: a randomised controlled trial of two types of bandage for treating venous leg ulcers. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong DG, Mossel J, Short B, Nixon BP, Knowles EA, Boulton AJM. Maggot debridement therapy: a primer. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2002;92:398-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien M. Exploring methods of wound debridement. Br J Community Nurs 2002;10-8. [PubMed]

- 7.Sherman RA, Hall MJ, Thomas S. Medicinal maggots: an ancient remedy for some contemporary afflictions. Annu Rev Entomol 2000;45:55-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambers L, Woodrow S, Brown AP, Harris PD, Phillips D, Hall M, et al. Degradation of extracellular matrix components by defined proteinases from the greenbottle larva Lucilia sericata used for the clinical debridement of non-healing wounds. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:14-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prete PE. Growth effects of Phaenicia sericata larval extracts on fibroblasts: mechanism for wound healing by maggot therapy. Life Sci 1997;60:505-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Plas MJA, van der Does AM, Baldry M, Dogterom-Ballering HCM, van Gulpen C, van Dissel JT, et al. Maggot excretions/secretions inhibit multiple neutrophil pro-inflammatory responses. Microbes Infect 2007;9:507-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horobin AJ, Shakesheff KM, Pritchard DI. Promotion of human dermal fibroblast migration, matrix remodelling and modification of fibroblast morphology within a novel 3D model by Lucilia sericata larval secretions. J Invest Dermatol 2006;126:1410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horobin AJ, Shakesheff KM, Pritchard DI. Maggots and wound healing: an investigation of the effects of secretions from Lucilia sericata larvae upon the migration of human dermal fibroblasts over a fibronectin-coated surface. Wound Repair Regen 2005;13:422-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bexfield A, Nigam Y, Thomas S, Ratcliffe NA. Detection and partial characterisation of two antibacterial factors from the excretions/secretions of the medicinal maggot Lucilia sericata and their activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Microbes Infect 2004;6:1297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huberman L, Gollop N, Mumcuoglu KY, Block C, Galun R. Antibacterial properties of whole body extracts and haemolymph of Lucilia sericata maggots. J Wound Care 2007;16:123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huberman L, Gollop N, Mumcuoglu KY, Breuer E, Bhusare SR, Shai Y, et al. Antibacterial substances of low molecular weight isolated from the blowfly, Lucilia sericata. Med Vet Entomol 2007;21:127-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas S, Andrews AM, Hay NP, Bourgoise S. The anti-microbial activity of maggot secretions: results of a preliminary study. J Tissue Viability 1999;9:127-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van der Plas MJA, Jukema GN, Wai S-W, Dogterom-Ballering HCM, Lagendijk EL, van Gulpen C, et al. Maggot excretions/secretions are differentially effective against biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;61:117-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mumcuoglu KY, Miller J, Mumcuoglu M, Friger M, Tarshis M. Destruction of bacteria in the digestive tract of the maggot of Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J Med Entomol 2001;38:161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wayman J, Nirojogi V, Walker A, Sowinski A, Walker MA. The cost effectiveness of larval therapy in venous ulcers. J Tissue Viability 2000;10:91-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soares MO, Iglesias CP, Bland JM, Cullum N, Dumville JC, Nelson EA, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of larval therapy for leg ulcers. BMJ 2009;338:b825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iglesias CP, Birks Y, Nelson EA, Scanlon E, Cullum NA. Quality of life of people with venous leg ulcers: a comparison of the discriminative and responsive characteristics of two generic and a disease specific instruments. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1705-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews JN, Altman DG, Campbell MJ, Royston P. Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ 1990;300:230-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware JE, Koninski M. SF-36. Physical and mental health summary scores: a manual for users of version 1.2. Lincoln, RI: Qualitymetric, 2001.

- 24.Tentolouris N, Petrikkos G, Vallianou N, Zachos C, Daikos GL, Tsapogas P, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in infected and uninfected diabetic foot ulcers. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006;12:186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lecornet E, Robert J, Jacqueminet S, Van Georges H, Jeanne S, Bouilloud F, et al. Preemptive isolation to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus cross-transmission in diabetic foot. Diabetes Care 2007;30:2341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson M. The benefits of larval therapy in wound care. Nurs Stand 2004;19:70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman R. Age-old therapy gets new approval. Adv Skin Wound Care 2005;18:12-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherman RA, Pechter EA. Maggot therapy: a review of the therapeutic applications of fly larvae in human medicine, especially for treating osteomyelitis. Med Vet Entomol 1988;2:225-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas S, Jones M, Shutler S, Jones S. Using larvae in modern wound management. J Wound Care 1996;5:60-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horn KL, Cobb AH Jr, Gates GA. Maggot therapy for subacute mastoiditis. Arch Otolaryngol 1976;102:377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horobin AJ, Shakesheff KM, Woodrow S, Robinson C, Pritchard DI. Maggots and wound healing: an investigation of the effects of secretions from Lucilia sericata larvae upon interactions between human dermal fibroblasts and extracellular matrix components. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:923-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]