Abstract

A series of ferrocenyl ester complexes, varying the lipophilic character of the pendant groups, was prepared and characterized by spectroscopic and analytical methods. The syntheses of Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2, Fe(CpCOOCH3) (CpCOO CH2CH3), and Fe(CpCOOCH2CH3)2 are reported. The solid-state structure of Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 has been determined by X-ray crystallography. Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 has the cyclopentadienyl rings virtually in an eclipsed conformation with the pendant groups not completely opposite to each other. Cyclic voltammetry characterization showed that the functionalized ferrocenes oxidize at potentials, Epa, higher than ferrocene as a result of the electro withdrawing effect of the pendant groups on the cyclopentadienyl ligand. The cytotoxicities of Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH2OH)2, Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH=CH2)2, Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2, Fe(CpCOOCH3)(CpCOOCH2CH3), and Fe(CpCOOCH2CH3)2 in colon cancer HT-29 and breast cancer MCF-7 cell lines were measured by the MTT biological viability assay and compared to ferrocene and ferrocenium. Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH=CH2)2 showed the best IC50 values, 180(10) μM for HT-29 and 190(30) μM for MCF-7 cell lines, with cytotoxicities similar to ferrocenium. The cytotoxic data suggest that as we increase the lipophilic character of the functionalized ferrocene, the cytotoxicity improves approaching to the cytotoxic activity of ferrocenium.

1. Introduction

Modern organometallic chemistry has been greatly influenced by the accidental discovery of bis(cyclopentadienyl)iron(II) (ferrocene) in 1951 [1, 2]. In fact, ferrocene (Cp2Fe) has been the most extensively studied organometallic species. Its applications in catalysis, organic synthesis, and industrial processes are numerous [3–6]. The thermal stability, inert character in concentrated acid and base solutions as well as the redox properties of ferrocene makes this species a versatile compound in many research areas.

Until 1979, the biological properties of metallocenes were unexplored. The report of titanocene dichloride (Cp2TiCl2) as the first metallocene to possess antitumor activity opened a new area of research, bioorganometallics, which has been developing rapidly in the last twenty eight years [7, 8].

In 1984, Köpf-Maier et al. reported the anticancer activity of ferrocenium complex in Ehrlich ascites tumor [9]. Since then, ferrocene has been studied for potential biological and medicinal applications [8, 10, 11]. Originally, the oxidized species of ferrocene, ferrocenium (Cp2Fe+) was reported to be responsible for the cytotoxic properties on DNA mediated through its capacity to generate oxygen-free radical species [12, 13]. Ferrocene has been recently reported to have antitumor properties due to the metabolic formation of ferrocenium ions which induces oxidative damage to DNA [14, 15]. As a result, many functionalized ferrocenes have been prepared and tested in cancer cells [11].

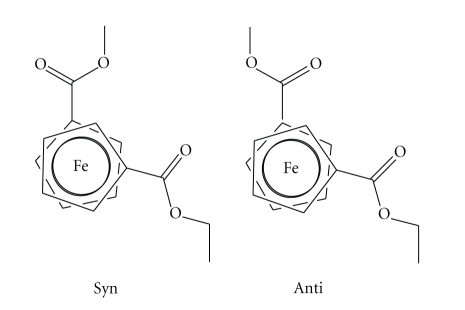

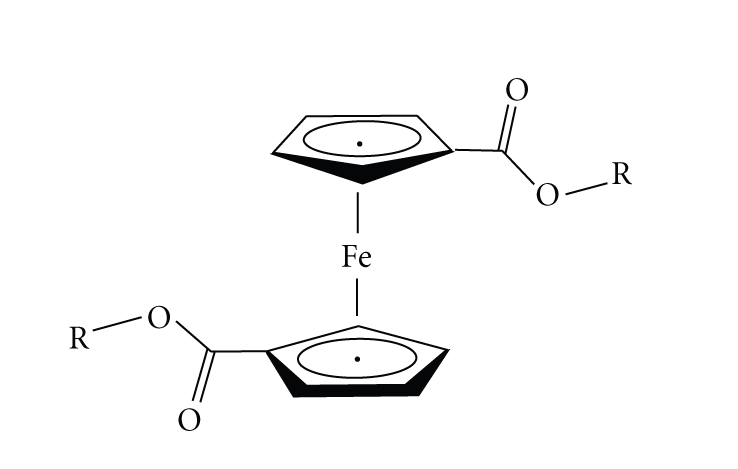

We have initiated a project on functionalized ferrocene chemistry, with pendant groups (functional groups, R) on the Cp rings varying their polar and lipophilic characters, see Scheme 1. The objective of this study is to understand how the polar and lipophilic characters of the pendant groups change the anticancer activity of the corresponding ferrocenyl derivatives. We have investigated the synthesis, structure, electrochemistry, and cytotoxic properties of five ferrocenyl esters in HT-29 colon cancer and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines. The objective of this study is to report these novel findings.

Scheme 1.

Structure of ferrocenyl ester complexes. R = CH3, CH2CH3, CH2CH2OH, and CH2CH=CH2.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Structure

The syntheses of Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2, Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH=CH2)2, and Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH2OH)2 have been reported previously [16, 17]. We applied the methodology developed by Busetto et al. to synthesize Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)2 and Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)(C5H4CO2CH3) (mixed ferrocene) [17]. Interestingly, using this synthetic methodology, the reaction of FeCl2 and one equivalent of NaC5H4CO2CH2CH3 and NaC5H4CO2CH3, even at room temperature, allowed the selective incorporation of two distinct functionalized Cp ligands, affording the mixed ferrocene complex in good yield without the formation of Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 and Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)2.

The NMR, IR, and elemental analysis corroborate the identities of the ferrocenyl ester complexes. The IR spectral data showed ν(C=O) broadbands at 1708 cm−1 (Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)2 and 1712 cm−1 (Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)(C5H4CO2CH3) corresponding to the carbonyl groups of the esters. In the 1H NMR spectrum, Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)2 exhibits two set of resonances at 4.42 and 4.84 ppm. These Cp protons exhibit coupling belonging to an AA′BB′ spin system. For the Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)(C5H4CO2CH3), the 1H NMR spectrum shows two sets of resonances at 4.42 and 4.85 ppm corresponding to the Cp protons of C5H4CO2CH2CH3 and C5H4CO2CH3 rings. While we might expect four sets of resonances in the vinyl region corresponding to two different substituted Cp rings, the fact that we observed only two sets suggests overlapping between these Cp proton signals. Particularly interesting in the 13C NMR spectrum, at room temperature, two sets of resonances for each carbon atom are observed in a ratio of 1:1. This suggests that two possible conformational diastereoisomers, syn and anti, coexist in solution as discussed below (Scheme 2) [18].

Scheme 2.

Conformational diastereoisomers of Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)(C5H4CO2CH3).

In solution, rapid ring oscillation about Cp–Fe–Cp axis allows H2 and H5 (H2′ and H5′) and H3 and H4 (H3′ and H4′) to become equivalents. This situation applies for both substituted Cp rings. Since both Cp rings have ester groups, overlapping of the H2/H5 and H2′/H5′, H3/H4 and H3′/H4′ signals in the 1H NMR spectrum is expected. However, the position of the ester groups yields to conformational diastereoisomers, syn and anti, which differ in the orientation of the carbonyl groups [18]. This condition applies when the C(Cp)–C(CO) bond is slow in the NMR scale time. When the rotation is fast, having enough energy to overcome the rotational barrier of the C(Cp)–C(CO) bond, such stereolabile chirality disappears. In the 13C NMR spectrum, the carbonyl orientation (syn and anti) makes significantly different magnetic environment on the Cp carbons as well as on the carbonyl groups such that two sets of resonances corresponding to syn and anti conformers can be observed. Variable temperature NMR studies, in toluene-d8, showed that at 80°C in the 1H spectrum, the multiplet signal at 4.85 ppm became a single line and the multiplet at 4.43 ppm broadened. These signals belong to the Cp rings. In the 13C NMR spectrum at 80°C, the carbon signals of one conformer begin to increase in intensity at expense of the other conformer, reaching a ratio of 1:2. This suggests that conformational diastereoisomers, syn and anti, at room temperature, have very similar stability but at high temperature, one diastereoisomer (presumably) anti becomes more populated.

In general, the present synthetic route developed by Busetto et al. [17] for the ferrocenyl ester complexes (Cp functionalization and formation of the corresponding functionalized ferrocene) represents a convenient alternative procedure for the functionalization of metallocenes and has been used by our group to synthesize functionalized titanocenes [19].

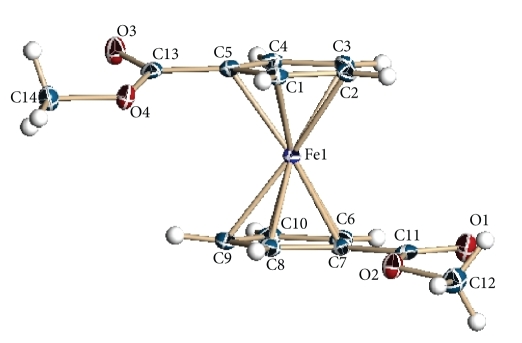

The solid-state structure of Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 was investigated by single-crystal X-ray diffraction, see Figure 1. Crystal data and structure refinement are summarized in the Supplementary Material available online at doi:10.1155/2009/420784 (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and the deposition number is CCDC 705387). Bonding parameters are included in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 1.

Solid-state structure of Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 drawn 50% thermal ellipsoids. Average Fe-Cp bonds, Fe(C1–C5) 2.049(28) Å and Fe(C6–C10) bond 2.048 (11) Å. Torsion angles for C(8)–C(7)–C(11)–O(2) 6.9(4)° and O(4)–C(13)–C(5)–C(1) 15.2(4)°.

As shown by X-ray, this ferrocene is a sandwich complex with the cyclopentadienyl ligands adopting an eclipsed conformation and with the pendant groups not completely opposite to each other. The average Fe–C(Cp) distances for Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 are 2.049 and 2.048 which is very similar to those reported for ferrocene, 2.045 [20]. The shortest Fe–C(Cp) bond distances are on C(5) and C(7). The shorter bond distances could be attributed to the inductive (electro-withdrawing) effect of the ester groups on these carbon atoms. The ester groups are not coplanar with the Cp ring, one of the OCH3 is bent toward the iron atom (below the Cp plane) with a torsion angle of 15.2° while the other is bent away from the iron atom by 6.9°. The C(Cp)–C(CO) bonds (C(5)–C(13) and C(7)–C(11)) are somewhat shorter than a typical C-C single bond, 1.477(4) versus 1.54 (for a single bond), suggesting these bonds have partial double bond character as a result of conjugation with the Cp π system [21]. The later might explain the high C(Cp)–C(CO) rotational barrier encountered in the Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH3)(C5H4CO2CH3) complex. In addition, the two CO2Me groups are anti to each other.

While the solid structure of Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 has been reported previously, our solid-state structure has a fundamental difference to that published by Cetina et al. [22]. That is, in the lattice, they determined a hydrogen bonding network between the carbonyl group and the CH3 of the adjacent molecule. We could not determine such hydrogen bonding network between the carbonyl group and the CH3 of the adjacent molecule even though our data was collected at lower temperature (173 K versus 293 K) and we obtained better refinement parameter (R (I > 2 sigma (I)) 0.0397 versus 0.046).

2.2. Cyclic Voltammetry

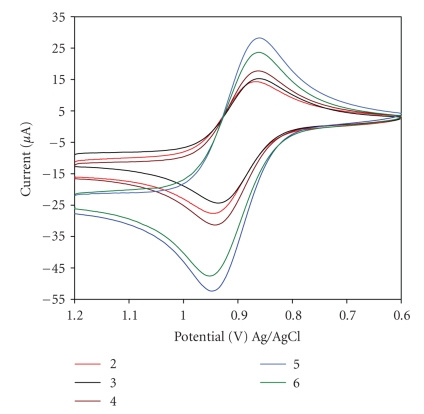

Electrochemical characterization of the subject complexes was performed by mean of cyclic voltammetry (CV). It is well known that ferrocene easily undergoes one electron oxidation to form ferrocenium (Cp2Fe+) in a reversible manner. Thus, we investigated the functionalized ferrocenes electrochemical behaviors and compared to ferrocene in organic solvent. Table 1 presents the CV results. As it can be seen in the cyclic voltammograms (Figure 2), ferrocene and Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2, as well as all the remaining functionalized ferrocenes undergo a reversible redox process with an i pa/ i pc ratio close to one. All the functionalized ferrocene demonstrated oxidation potentials, E pa, higher than ferrocene. This is the result of the electro-withdrawing (inductive) effect of the ester groups on the Cp rings. Since ferrocene is known to undergo one-electron redox process, it can be deduced that the subject complexes also undergo one-electron redox change. Thus, this major redox process on the functionalized ferrocenes is associated to the ferrocene/ferrocenium couple.

Table 1.

Redox potential of ferrocenyl esters in CH3CN 1M CH3CN 1M [NBun 4]PF6 at a scan rate of 100 mV/s, referenced to ferrocene/ferrocenium redox couple. Ferrocene concentration of 2 × 10−3 M. E1/2 is an average of the anodic and cathodic peaks potentials.

| Complex | E1/2 (mV) | ΔE (mV) |

|---|---|---|

| Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 | 454 | 75 |

| Fe(CpCOOCH2CH3)2 | 448 | 74 |

| Fe(CpCOOCH3)(CpCOOCH2CH3) | 452 | 78 |

| Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH=CH2)2 | 453 | 85 |

| Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH2OH)2 | 456 | 89 |

Figure 2.

Cyclic voltammograms of complexes 2: Fe(CpCOOMe)2, 3: Fe(CpCOOEt)2, 4: Fe(CpCOOMe)(CpCOOEt), 5: Fe(CpCOOCH2CH=CH2)2, and 6: Fe(CpCOOCH2CH2OH)2 (2 × 10−2 M) in CH3CN (1 × 10−3 M Bu4NPF6) at room temperature. The working electrode was a platinum disk, reference electrode was Ag/AgCl, and the scan rate was 100 mv/s.

2.3. Cytotoxic Studies—3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT): Colorimetric Assay for Cytotoxicity Analysis on the Colon Cancer HT-29 and Breast MCF-7 Cell Lines

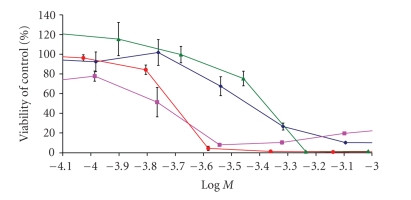

The cytotoxicities of the ferrocenyl ester complexes on the HT-29 colon cancer and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines were measured using a slightly modified MTT assay [23, 24]. Ferrocene was initially evaluated at time intervals of 72, 96, and 120 hours at concentrations that ranged from 10–1200 μM, in HT-29, to determine its optimal activity (Supplementary Figure 1S). Ferrocene displayed comparable activity at all three time intervals, with an IC50 value of 3.6 × 10−4 M. Since exposing the cells to ferrocene at longer periods of time did not increase its cytotoxic activity, all subsequent experiments were performed at a drug exposure time of 72 hours. Ferrocene, ferrocenium, and the functionalized complexes (–CO2R, R=Me, Et) were tested in concentrations which ranged from 10–1200 μM. In addition, two control experiments were run 100% Medium and 5% DMSO/95% Medium. Both control experiments behaved identical demonstrating that 5% DMSO in the Medium does not have any cytotoxic effect on these cells. Table 2 summarizes the results of the cytotoxicity experiments and Figure 3 depicts the cytotoxic curves from MTT assays showing the effect of the ferrocene complexes on the viability of HT-29 colon cancer cell line. The IC50 value represents the concentration of the ferrocene at which the cell growth is inhibited by 50%. It can be noted that bis(carboethoxycyclopentadienyl)ferrocene showed activity comparable to ferrocene, with values of 370 and 360 μM, respectively but it has less cytotoxicity than ferrocenium (180 μM). In contrast, (carboethoxycyclopentadienyl)-(carbomethoxycyclopentadienyl)-ferrocene and the bis(carbomethoxycyclopentadienyl)-ferrocene exhibited less cytotoxic activity than ferrocene and ferrocenium. The carbomethoxy functionalization has been shown previously to inactivate or lower the cytotoxic activity of resulting titanocene complexes [19]. The present results clearly show how the presence of the carbomethoxy substituent in the cyclopentadienyl ring lowers the activity of ferrocene in a stepwise manner, being the bis(carbomethoxy)ferrocene less active than (carbomethoxy)(carboethoxy)ferrocene. The carboethoxy functionalization does not improve the activity of the ferrocene complexes as compared to ferrocene.

Table 2.

Cytotoxicities of ferrocenes studied on HT-29 colon cancer and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines at 72 hours, as determined by MTT assay. IC values are the average of four independent measurements with their standard deviations ().

| HT-29 | MCF-7 | |

|---|---|---|

| Complex | IC50 (μM) | IC50 (μM) |

| FeCp2 | 360(30) | 1500(100) |

| Fe(Cp–COOEt)2 | 370(10) | 250(20) |

| Fe(Cp–COOMe)(Cp–COOEt) | 500(20) | 320(30) |

| Fe(Cp–COOMe)2 | 720(50) | 520(20) |

| Fe(CpCOOCH2CH2OH)2 | 370(20) | 340(30) |

| Fe(CpCOCH2CHCH2)2 | 180(10) | 190(30) |

| Fe[Cp2]BF4 | 180(10) | 150(05) |

Figure 3.

Dose-response curves for functionalized cyclopentadienyl ferrocenes against HT-29 cells at 72 hours drug exposure. Legend: ferrocene-diamonds, bis(carbomethoxy)-squares, bis(carboethoxy)-triangles, and (carbomethoxy)(carboethoxy)-circles.

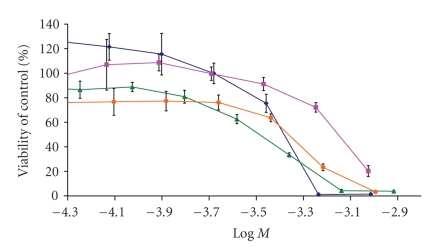

Other ferrocenyl complexes, varying the lipophilic character of the carboalkoxy groups, were also evaluated for cytotoxic activity against HT-29 cells. Ferrocene complexes with either terminal alcohol or allyl groups were tested in concentrations that ranged from 13 to 1300 μM at a 72-hour time interval. IC50 values for these complexes are also summarized in Table 2, and Figure 4 shows the cytotoxic curves for these complexes along with ferrocene and ferrocenium for comparison. The ferrocene alcohol complex shows an IC50 value of 370 μM which is comparable to ferrocene, while (allyl) complex shows higher cytotoxic activity than ferrocene and equal to the ferrocenium at the time interval studied, with an IC50 value of 180 μM.

Figure 4.

Dose-response curves for functionalized ferrocene complexes on HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cells at 72 hours. Complex with terminal alcohol (diamonds), complex with terminal allyl (squares), ferrocene (triangles), and ferrocenium ion (circles).

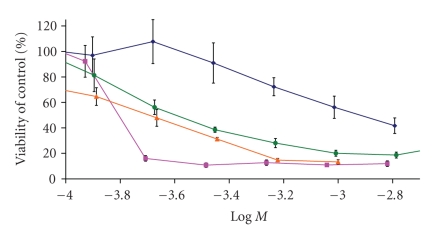

The initial work performed by Kopf-Maier et al. demonstrated that ferrocenium possesses in vivo anticancer activity in breast cancer [9]. Based on this precedent, we investigated our functionalized ferrocenes in MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. Surprisingly, ferrocene showed to be less cytotoxic in breast cancer than in colon cancer. With regard to the functionalized ferrocenes and similar to the results on HT-29 cell line, a pattern in the cytotoxicity as we change the functional group (pendant group) is evident. First, in the ferrocenyl with carboalkoxy groups, the incorporation of methyl ester (–CO2CH3) groups on the Cp rings decreases the cytotoxic activity of the resulting complexes. Second, see Figure 5, the increase in the lipophilic character on the carboalkoxy substituents such as in Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH=CH2)2, where the ethyl group is substituted by an olefin, increases the cytotoxic activity. Such behavior has been reported previously by two-independent research groups, as described below [12, 25].

Figure 5.

Dose-response curves for functionalized ferrocene complexes on MCF-7 breast cancer cells at 72 hours. Ferrocene(diamonds), ferrocenium(squares), bis(carboethoxy)(triangles), and terminal allyl (circles).

A wide variety of ferrocenyl derivatives have been synthesized by several research groups aimed to improve their anticancer activity as well as to understand the structure-activity relationship. Very active ferrocenyl derivatives have been synthesized containing estrogen receptor modulators as pendant groups [26]. Among them, 1,1′-bis-(4′-hydroxyphenyl)-2-ferrocenyl-but-1-ene showed strong antiproliferative activity in both hormone-dependent (MCF-7) and hormone-independent (MDA-MDA231) breast cancer cells with IC50 = 0.7 and 0.6 μM, respectively [26]. On the other hand, ferrocenyl carbohydrate conjugates prepared by Orvig et al. showed IC50 values between 87–468 μM on HTB-129 human breast cancer cell line [27]. Our ferrocenyl esters showed IC50 values similar to those of the ferrocenyl carbohydrates [27] and ferrocenium derivatives tested on MCF-7 cell line: ferroceniumcarboxylic acid tetrafluoroborate (IC50 = 340 μM), decamethylferrocene tetrafluoroborate (IC50 = 37 μM), 1,1′-dimethylferrocenium tetrafluoroborate (IC50 = 320 μM), and ferrocenium boronic acid tetrafluoroborateIC50 = 317 μM) [12]. It should be clearly noticed that, as reported previously, the increase in the lipophilic character on the ferrocene or ferrocenium complex increases the cytotoxic activity [12, 25].

For colon cancer, the cytotoxic data is more limited for a more meaningful comparison and assessment. On a recent review on the medicinal properties of ferrocenes, it was described a series of ferrocene conjugates (functionalized) anchored to polyaspartimides (water soluble carrier polymers) and evaluated on Colo and Hela colon cancer cell lines [11, 28]. The IC50 values determined are in the 10−4–10−5 M range, analogous to some of our most active species. From these studies, Neuse et al. found that increasing the hydrophilicity of the polyaspartimide side chains does not necessarily improve the cytotoxicity of the resulting ferrocenes, similar to our findings [28]. On the other hand, opposite to our findings, Kenny et al. studied the antiproliferative effect of a series of N-(ferrocenyl)benzoyl dipeptide esters on H1229 lung cancer cells and found that increasing the alkyl chain length of the amino acid lower the cytotoxic activity [29]. However, since the data come from different cancer cell lines, the comparison of the IC50 values becomes less accurate.

Finally, an important conclusion derived from this study is that minor changes in the pendant group on the Cp ring may have notable impact in the cytotoxic activity of the resulting ferrocenes. This is in good agreement with previous reports [12, 25]. Increasing the lipophilic character of the ferrocenyl esters apparently improves their biological activity, as a result of better transport of these species into the target place inside the cell [12, 13, 25]. This increased lipophilic character on the ferrocenes increases the cell uptake (improving cell membrane permeability of the ferrocene), and more ferrocene molecules could become available inside the cell to express their activity. It has been proposed by Lander et al. that not only ferrocenium cation but also ferrocene is able to express oxidative stress [15]. Ferrocene is able to generate H2O2 by autooxidation, forming ferrocenium ions. The immune-stimulatory properties of ferrocene are postulated to be mediated by redox-sensitive signaling proteins [15].

3. Experimental

3.1. General Procedure

All reactions were performed under an atmosphere of dry nitrogen using Schlenk glassware or a glovebox, unless otherwise stated. Reaction vessels were flame dried under a stream of nitrogen, and anhydrous solvents were transferred by oven-dried syringes or cannula. Tetrahydrofuran was dried and deoxygenated by distillation over K-benzophenone under nitrogen. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Brucker Vector-22 spectrometer with the samples as compressed KBr discs. The NMR spectra were obtained on a 500 MHz Bruker spectrometer. Elemental analyses were obtained from Atlantic Microlab, Inc., Ga, USA. Electrochemical characterization was carried out on a BAS CV050W voltammetric analyzer of Bioanalytical Systems, Inc. with a three-stand electrode cell. Cyclic voltammetric experiments were performed in deoxygenated CH3CN solution of ferrocene complexes with 1M of [NBun 4PF6 as supporting electrolyte and ferrocene complex concentration of 2 × 10−3M. The three electrodes used were platinum disk as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode, and Pt wire as an auxiliary electrode. The working electrode was polished with 0.05 μm alumina slurry for 1–2 minutes, and then rinsed with double-distilled and deionized water. This cleaning process is done before each CV experiment and a sweep between 0 and 2000 mV is performed on the electrolyte solution to detect any possible deposition of ferrocene on the electrode surface.

Dimethyl carbonate, diethyl carbonate, diallyl carbonate, ethylene carbonate, diethyl ether (anhydrous ≥99.7%), anhydrous FeCl2, [Cp2Fe]BF4, and CDCl3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. NaCp was prepared in situ by reacting freshly distilled cyclopentadiene and NaH in THF. Silica gel was heated at about 200°C while a slow stream of dry nitrogen was passed through it.

The syntheses of sodium 1-carbomethoxycyclopentadienide (NaCpCOOCH3) and sodium 1-carboethoxycyclopentadienide (NaCpCOOCH2CH3) have been reported previously by our group [18].

The colon cancer cell line HT-29 and the breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF7 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection, Va, USA, and were at 37°C and 95% Air/5% CO2. Growth medium for HT-29 was McCoy's 5A complete medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) antibiotic/antimycotic. Growth medium for MCF7 was Eagle's Minimum Essential Media supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 1% (v/v) antibiotic/antimycotic, nonessential amino acids, and 0.01 mg/mL bovine insulin. MTT and Triton X-100 used for the cytotoxic assay were obtained from Sigma. All MTT manipulations were performed in a dark room.

3.2. Synthesis

3.2.1. Synthesis of 1,1′-bis(carbomethoxy)-ferrocene (Fe(CpCOOCH3)2)

To a solution of NaCpCOOCH3 (0.47 g, 3.1 mmol) in THF 20 mL, was added solid FeCl2 (0.2 g, 1.5 mmol). The solution was stirred for 24 hours at room temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and CH2Cl2 was added; the red suspension was first filtered on a Celite pad and then chromatographed on silica gel eluting with Et2O to give 0.45 g (95%) of orange viscous oil. The product was redissolved in chloroform/hexane (1:9) at −20°C and orange solid could be obtained.1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 3.85(s, 6H; –OCH3), 4.43[t, 4 H, 3 J(H, H) = 1.5 Hz, AA′BB′; Cp], 4.85[t, 4H, 3 J (H, H) = 1.5 Hz; AA′BB′; Cp]. 13CNMR(125 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 51.71(–OCH3), 71.61(CH; Cp), 72.62(CH; Cp), 72.89(ipso-C; Cp), 170.82(C=O). IR (KBr, cm−1): 2957, 1703, 1470, 1288, 1197, 1147, 965, 780. Anal. Calcd for C14H14O4Fe: C, 55.67; H, 4.64. Found: C, 56.01; H, 4.74.

3.2.2. Synthesis of 1,1′-bis(carboethoxy)-ferrocene (Fe(CpCOOCH2CH3)2

To a solution of NaCpCOOCH2CH3 (0.50 g, 3.16 mmol) in THF 20 mL, was added solid FeCl2 (0.2 g, 1.58 mmol). The solution was stirred for 24 hours at room temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and CH2Cl2 was added; the red suspension was first filtered on a Celite pad and then chromatographed on silica gel eluting with Et2O to give 0.48 g (92%) of orange viscous oil. The product was resolved in chloroform/hexane (1:12) at −20°C and orange solid could be obtained. 1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 1.38(t, 6H, 3 J (H, H) = 7.0 Hz; –OCH2CH3), 4.31(q, 4H, 3 J (H, H) = 7.0 Hz; –OCH2CH3), 4.42[t, 4H, 3 J (H, H) = 1.5 Hz, AA′BB′; Cp], 4.84[t, 4H, 3 J (H, H) = 1.5 Hz; AA′BB′; Cp]. 13CNMR(125 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 14.53(–OCH2CH3), 60.43(–OCH2CH3), 71.53(CH; Cp), 72.71(CH; Cp), 73.16(ipso-C; Cp), 170.43(C=O). IR (KBr, cm−1): 2985, 2936, 1708, 1479, 1457, 1379, 1282, 1144, 1030, 1017, 774. Anal. Calcd for C16H18O4Fe: C, 58.22; H, 5.46. Found: C, 58.19; H, 5.48.

3.2.3. Synthesis of 1-(carbomethoxy)-1′-(carboethoxy)-ferrocene (Fe(CpCOOCH3) (CpCOOCH2CH3)

To a solution of NaCpCOOCH3 (0.23 g, 1.58 mmol) and NaCpCOOCH2CH3 (0.25 g, 1.58 mmol) in THF 20 mL, was added solid FeCl2 (0.2 g, 1.58 mmol). The solution was stirred for 24 hours at room temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and CH2Cl2 was added; the red suspension was first filtered on a Celite pad and then chromatographed on silica gel eluting with Et2O to give 0.46 g (92%) of orange viscous oil. The product was dissolved in chloroform/hexane (1:10) at −20°C and orange solid could be obtained.1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 1.39(t, 3H, 3 J (H, H) = 7.0 Hz; –OCH2CH3), 3.85, 3.86*(s, 3H; –OCH3), 4.32(q, 2H, 3 J (H, H) = 7.0 Hz; –OCH2CH3), 4.43[m, 4H; Cp], 4.85[m, 4H; Cp].13CNMR(125 MHz, CDCl3): δ(ppm) 14.52, 14.55*(–OCH2CH3), 51.76(–OCH3), 60.46, 60.48*(–OCH2CH3), 71.57, 71.61*(CH; Cp), 72.73, 72.77*(CH; Cp), 72.86, 73.21*(ipso-C; Cp), 170.43, 170.49*(C=O), 170.87, 170.95*(C=O). IR (KBr, cm−1): 2995, 2950, 1712, 1472, 1284, 1143, 1030, 774, 514. Anal. Calcd for C15H16O4Fe: C, 57.00; H, 5.07. Found: C, 57.19; H, 5.08.

The two complexes [Fe(C5H4CO2CH2CH=CH2)2] and [Fe{C5H4CO2(CH2)2OH}2] were prepared as described by Busetto et al. from sodium cyclopentadenide and diallyl carbonate or solid ethylene carbonate [17].

3.3. Cytotoxic Assay

Biological activity was determined using the MTT assay originally described by Mossman [19a] but using 10% Triton in isopropanol as a solvent for the MTT formazan crystals [19b]. HT-29 and MCF7 cells were maintained at 37°C and 95% Air/5% CO2 in McCoy's 5A (ATCC) complete medium, which had been supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (ATCC) and 1% (v/v) antibiotic/antimycotic (Sigma). Asynchronously, growing cells were seeded at 1.5 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates containing 100 μL of complete growth medium, and allowed to recover overnight. Various concentrations of the complexes (10–1300 μM) dissolved in 5% DMSO/95% Medium were added to the wells (eight wells per concentration, experiments performed in quadruplicate plates). The complexes solutions were prepared first by dissolving the corresponding ferrocene in DMSO and then Medium was added to a final composition of 5% DMSO/95% Medium. In addition to the cells treated with the ferrocenes, two controls experiments were run one without any addition of solvent mixture (5% DMSO/95% Medium) and one adding 5% DMSO/95% Medium to the cells. Both control experiments behaved identical, showing that 5% of DMSO in the Medium did not render toxic to these types of cells. The cells were incubated for an additional 70 hours. After this time, MTT dissolved in complete growth medium was added to each well to a final concentration of 1.0 mg/mL and incubated for two additional hours. After this period of time, all MTTs containing medium were removed, cells were washed with cold PBS and dissolved with 200 μL of a 10% (v/v) Triton X-100 solution in isopropanol. After complete dissolution of the formazan crystals, well absorbances were recorded in triplicates on a 340 ATTC Microplate Reader (SLT Lab Instruments) at 570 nm with background subtraction at 630 nm. Concentrations of compounds required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50% (IC50) were calculated by fitting data to a four-parameter logistic plot by means of SigmaPlot software from SPSS, Ill, USA.

3.4. X-Ray Crystallographic Analysis

A light orange needle crystal with 0.15 × 0.04 × 0.01 mm in size was mounted on a cryoloop with Paratone oil. Data was collected in a nitrogen gas stream at −173°C on a Bruker Smart system. Data collection was 99.6% complete to 25° in θ. The data was integrated using the Bruker SAINT software program. The structure was solved by direct methods and all nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically by full-matrix least-squares (SHELXL-97). The crystal structure has been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and the deposition number is CCDC 705387.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material contains crystallography data, bonding parameters, and torsion angles for Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 and cytotoxic plot for ferrocene on HT-29 colon cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

E. Meléndez acknowledges the NIH-MBRS SCORE Programs at both the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, USA and the Ponce School of Medicine for financial support via NIH-MBRS-SCORE Program Grant no. S06 GM008239-23 and the PSM-Moffitt Cancer Center Partnership 1U56CA126379-01. In addition, E. Meléndez thanks NSF-MRI Program for providing funds for the purchasing of the 500 MHz NMR instrument, School of Crystallography, the University of California, San Diego, Calif, USA, and Professor Arnold Rheingold and Dr. Antonio Dipasquale for the X-ray facility and to the Sloan Foundation for financial support in the form of a graduate fellowship to R. Hernández.

References

- 1.Kealy TJ, Pauson PL. A new type of organo-iron compound. Nature. 1951;168(4285):1039–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller SA, Tebboth JA, Tremaine JF. Dicyclopentadienyliron. Journal of the Chemical Society. 1952:632–635. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Togni A, Hayashi T, editors. Ferrocenes: Homogeneous Catalysis/Organic Synthesis/Materials Science. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gómez Arrayás R, Adrio J, Carretero JC. Recent applications of chiral ferrocene ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition. 2006;45(46):7674–7715. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Togni A, Halterman RL, editors. Metallocenes. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atkinson RCJ, Gibson VC, Long NJ. The syntheses and catalytic applications of unsymmetrical ferrocene ligands. Chemical Society Reviews. 2004;33(5):313–328. doi: 10.1039/b316819k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Köpf H, Köpf-Maier P. Titanocene dichloride—the first metallocene with cancerostatic activity. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition in English. 1979;18(6):477–478. doi: 10.1002/anie.197904771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaouen G, editor. Bioorganometallics. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köpf-Maier P, Köpf H, Neuse EW. Ferricenium complexes: a new type of water-soluble antitumor agent. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 1984;108(3):336–340. doi: 10.1007/BF00390468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Staveren DR, Metzler-Nolte N. Bioorganometallic chemistry of ferrocene. Chemical Reviews. 2004;104(12):5931–5985. doi: 10.1021/cr0101510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fouda MFR, Abd-EIzaher MM, Abdelsamaia RA, Labib AA. On the medicinal chemistry of ferrocene. Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 2007;21(8):613–625. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabbì G, Cassino C, Cavigiolio G, et al. Water stability and cytotoxic activity relationship of a series of ferrocenium derivatives. ESR insights on the radical production during the degradation process. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;45(26):5786–5796. doi: 10.1021/jm021003k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osella D, Mahboobi H, Colangelo D, Cavigiolio G, Vessières A, Jaouen G. FACS analysis of oxidative stress induced on tumour cells by SERMs. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2005;358(6):1993–1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura H, Miwa M. DNA cleaving activity and cytotoxic activity of ferricenium cations. Chemistry Letters. 1997;26(11):1177–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovjazin R, Eldar T, Patya M, Vanichkin A, Lander HM, Novogrodsky A. Ferrocene-induced lymphocyte activation and anti-tumor activity is mediated by redox-sensitive signaling. The FASEB Journal. 2003;17(3):467–469. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0558fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spradau TW, Katzenellenbogen JA. Preparation of cyclopentadienyltricarbonylrhenium complexes using a double ligand-transfer reaction. Organometallics. 1998;17(10):2009–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busetto L, Cassani MC, Albano VG, Sabatino P. Coordination chemistry of ester-functionalized Cp ligands. The atom-economy synthesis of Na[C5H4CO2(CH2)2OH], solid state structures of [Rh{C5H4CO2(CH2)2OH}(CO)2] and [Rh2{μ-(C5H4CO2CH2)2}(NBD)2] Organometallics. 2002;21(9):1849–1855. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonini BF, Fochi M, Lunazzi L, Mazzanti A. Conformational studies by dynamic NMR. 72. Stereolabile enantiomers of acyl and thioacyl ferrocenes. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2000;65(8):2596–2598. doi: 10.1021/jo991751q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao LM, Hernández R, Matta J, Meléndez E. Synthesis, Ti(IV) intake by apotransferrin and cytotoxic properties of functionalized titanocene dichlorides. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2007;12(7):959–967. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunitz JD, Orgel LE, Rich A. The crystal structure of ferrocene. Acta Crystallographica. 1956;9, part 4:373–375. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pauling L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond. 3rd edition. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cetina M, Jukić M, Rapić V, Golobič A. Ferrocene compounds. XXXVIII. Di-methyl ferrocene-1,1′-dicarboxylate. Acta Crystallographica Section C. 2003;59(6):m212–m214. doi: 10.1107/s0108270103008503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1983;65(1-2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denizot F, Lang R. Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival: modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1986;89(2):271–277. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James P, Neudörfl J, Eissmann M, Jesse P, Prokop A, Schmalz H-G. Enantioselective synthesis of ferrocenyl nucleoside analogues with apoptosis-inducing activity. Organic Letters. 2006;8(13):2763–2766. doi: 10.1021/ol060868f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vessières A, Top S, Pigeon P, et al. Modification of the estrogenic properties of diphenols by the incorporation of ferrocene. Generation of antiproliferative effects in vitro. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;48(12):3937–3940. doi: 10.1021/jm050251o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreira CL, Ewart CB, Barta CA, et al. Synthesis, structure, and biological activity of ferrocenyl carbohydrate conjugates. Inorganic Chemistry. 2006;45(20):8414–8422. doi: 10.1021/ic061166p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caldwell G, Meirim MG, Neuse EW, van Rensburg CEJ. Antineoplastic activity of polyaspartamide-ferrocene conjugates. Applied Organometallic Chemistry. 1998;12(12):793–799. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corey AJ, O'Donovan N, Mooney Á, O'Sullivan D, Rai DK, Kenny PTM. Synthesis, structural characterization, in vitro anti-proliferative effect and cell cycle analysis of N-(ferrocenyl)benzoyl dipeptide esters. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. In press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material contains crystallography data, bonding parameters, and torsion angles for Fe(C5H4CO2CH3)2 and cytotoxic plot for ferrocene on HT-29 colon cancer cells.