Dr Fontana is an Associate Professor of Medicine and the Medical Director of Liver Transplantation in the United States (US) at the University of Michigan Medical Center. Dr Fontana has been a leading investigator in the US Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG) for the past eight years. He is currently the Chair of the Ancillary Studies Committee and principal investigator of the long-term outcomes study of ALFSG patients. Dr Fontana is also a site investigator at the National Institutes of Health Drug Induced Liver Injury Network, which is prospectively enrolling patients with idiosyncratic drug hepatotoxicity due to prescription or complementary and alternative medicines (see http://dilin.dcri.duke.edu/ for further information).

Dr. Robert J Fontana is an Associate Professor of Medicine and the Medical Director of Liver Transplantation at the University of Michigan Medical Center, USA

PA: Tell us about the US ALFSG.

RJF: The US ALFSG is a network of 23 clinical sites and investigators interested in improving our understanding of the causes and outcomes of acute liver failure (ALF). Because ALF is an uncommon illness in western countries, with an estimated annual incidence of only one per 100,000 (ie, 2500 cases per year in the US), a multicentre network of referral centres provides a practical means to study this rare but potentially devastating illness. The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (US), under the leadership of William Lee, MD serves as the lead site and data-coordinating centre. We currently have an ongoing therapeutic trial of intravenous N-acetylcysteine versus placebo for non-acetaminophen (ACM)-induced ALF, and there are tentative plans to conduct a future study of moderate hypothermia in ALF patients with advanced encephalopathy. Recently, the adult ALFSG was renewed as a National Institutes of Health cooperative agreement through 2010, and Canada is now represented through the University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario) with Les Lilly, MD as the site investigator.

Consecutive patients with ALF (ie, international normalized ratio greater than 1.5 and encephalopathy onset within 26 weeks of presentation) are enrolled in the prospective observational study and followed for three weeks until recovery, transplantation or death. Detailed clinical data at presentation, serum, urine and liver tissue samples, and DNA for genetic testing have been collected in over 1000 adults since the study was initiated in 1998. Analysis of the first 308 patients enrolled demonstrated that ACM was the most common cause of ALF, accounting for 39% of cases, followed by a potpourri of idiosyncratic drug reactions in 13% (1). Interestingly, severe acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection accounted for only 4% and 7% of ALF, respectively, while 17% of cases were of indeterminate etiology. Overall, patient survival was 67% at three weeks, and 29% required emergency liver transplantation. The high proportion of ACM-induced ALF is in marked distinction to studies from the 1970s and 1980s, in which HAV and HBV were the most common etiologies of ALF, and ACM was not even mentioned (2,3). The shift in etiologies may be due to differing study methods, a reduced incidence of HAV/HBV due to vaccination, and increasing use of ACM-containing products versus acetylsalicylic acid for acute febrile illnesses in both children and adults to minimize the risk of Reye’s syndrome.

The extensive clinical and laboratory data, as well as the bank of serum and DNA samples, have provided a unique opportunity to conduct many important ancillary studies. Currently, there are over 40 active ancillary studies investigating topics ranging from laboratory and clinical predictors of susceptibility and liver regeneration to natural history and long-term neurological outcomes. We recently demonstrated that occult HBV, hepatitis E virus, SEN-V and parvovirus B19 infection do not account for the large proportion of indeterminate ALF cases (4–6). In addition, we learned that ALF patients with intracranial pressure monitors receive more interventions and undergo liver transplantation more frequently than nonmonitored patients, but they did not experience improved survival (7). I am hopeful that the ALFSG will continue to make important scientific contributions to our understanding of the etiopathogenesis and outcomes of this challenging disease.

PA: A recent study from the US ALFSG suggested that 48% of patients with ACM-induced ALF were taking medicinal or therapeutic doses rather than suicidal doses. Can you elaborate on these intriguing findings?

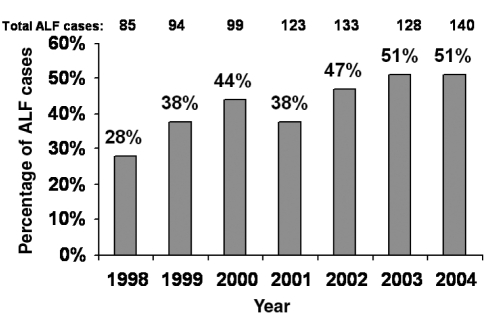

RJF: We recently published the outcomes of 275 consecutive patients with ACM-related ALF (8). First, we noted an alarming increase in the annual incidence of ALF due to ACM that rose from 28% in 1998 to 51% in 2004 (Figure 1). In addition, we found nearly 50% of ACM cases were nonintentional ‘therapeutic misadventures’. As you may recall, prior studies suggested that alcoholics taking excessive doses of ACM over several days or others receiving ACM-based analgesics for acute medical illnesses may rarely develop inadvertent hepatotoxicity (9,10). We were quite surprised to discover that 48% of ALF ACM cases were nonintentional in our prospective study. Although most of these patients were taking excessive doses of ACM, approximately 50% of the nonintentional group were consuming 4 g/day to 10 g/day, and 7% of the entire cohort reported ingesting less than 4 g/day of ACM. The majority (81%) of nonintentional overdose patients had either an acute or chronic painful medical condition, and 63% were taking a narcotic-ACM analgesic chronically. In addition, 38% of the nonintentional overdose group were consuming more than one ACM-containing product compared with 5% in the intentional group. Contrary to our expectations, there was no difference in the frequency of underlying depression, alcohol consumption or past history of substance abuse between the two patient groups.

Figure 1).

Acute liver failure (ALF) cases in the United States (US) attributable to acetaminophen (ACM) overdose. The US Acute Liver Failure Study Group (ALFSG) has identified an increasing incidence of ALF due to ACM between 1998 and 2004. Among the ACM-induced ALF cases, 48% were considered ‘nonintentional’ overdose cases wherein patients had taken excessive doses of ACM-containing products for medicinal purposes. Data provided by William Lee, MD, US ALFSG, December 2005

At presentation, the nonintentional overdose patients had significantly lower serum ACM levels (median 106 μmol/L versus 554 μmol/L, P<0.001) and presented later after symptom onset (median four days versus one day). In addition, they had lower serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels (3319 U/L versus 5326 U/L, P<0.001) but more advanced encephalopathy at presentation (53% grade ¾ versus 39% grade ¾, P=0.002). Contrary to prior retrospective studies, the nonintentional overdose patients did not have poorer outcomes despite a more delayed presentation with a similar proportion requiring liver transplantation (9% versus 7%) or having fatal outcomes (28% versus 29%).

Our study results have several important practical implications. First, the frequency of nonintentional ACM overdose cases is much higher than expected. The fact that this is occurring in multiple centres and the overall incidence is increasing over a short time period suggests that nonintentional ACM overdose is a substantial public health problem. Currently, it is estimated that there are 60,000 intentional ACM overdose cases each year in the US, with 500 fatalities (11). However, the incremental morbidity and mortality from nonintentional ACM overdose is unknown. If the frequency and distribution of ALF etiologies in the ALFSG are representative of the US, then there may be up to 500 nonintentional ACM overdose ALF cases each year with at least 150 deaths. Many of our ‘nonintentional’ overdose patients were seeing a physician for an acute or chronic medical problem. A recent study (12) from Chicago demonstrated that 7% of all emergency room patients were sent home on a prescription narcotic-ACM analgesic, but none of them had received instructions to reduce or stop other ACM-containing products. These data suggest that we need to better educate our patients and our colleagues of the hazards of excessive doses of ACM used for medicinal purposes. Fortunately, the majority of both intentional as well as nonintentional ACM overdose patients in the ALFSG study received N-acetylcysteine treatment (ie, 87% and 95%, respectively), which may partly explain the generally favourable outcomes in this patient group compared with other etiologies of ALF.

PA: How much ACM can a patient safely take on a daily basis? Is there a threshold dose for ACM hepatotoxicity?

RJF: ACM is a safe and effective analgesic when used in recommended doses of less than 4 g/day. In fact, ACM is the most commonly used medication worldwide on a daily basis. However, when taken in excess, a dose-dependent risk of hepatotoxicity ensues due to enhanced formation of the highly reactive intermediate metabolite (N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine [NAPQI]) which can bind to intracellular proteins and lead to hepatocyte death. The risk of hepatotoxicity can be estimated using an algorithm based upon the initial serum ACM level after a single time point ingestion (ie, the Rumack nomogram) (13). However, because an accurate history of the amount and time of ACM ingested often cannot be obtained in cases of suicidal intent or in patients with an altered mental status, the Rumack nomogram cannot be applied to many intentional overdose patients or to any of the nonintentional patients who overdose over several days. Nonetheless, most experts feel that a maximum daily dose of 4 g/day can be tolerated by most adults without untoward hepatotoxicity (14). However, ACM has been so heavily marketed as a safe pain reliever, that it has now been incorporated into a myriad of over-the-counter medications. Currently, more than 100 products ranging from allergy, sleep and stomach remedies contain varying amounts of ACM (Table 1), and some of the liquid preparations such as Comtrex (Bristol-Myers Squibb, USA) contain 1000 mg in each teaspoon. I would hazard to say that most practicing physicians, including gastroenterologists and hepatologists, are not aware of the ACM content in these products, let alone our patients or the general public. In addition, there are studies demonstrating that patients frequently under-report their use of over-the-counter and alternative medications to medical doctors for a variety of reasons (15). Therefore, the potential for inadvertent ACM overdose is substantial in our society due to the ubiquitous presence of ACM in so many seemingly ‘safe’ products (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Over-the-counter products that contain acetaminophen (ACM)

| Trade name | Active ingredients | ACM dose (mg/tablet) |

|---|---|---|

| Actifed products (Pfizer Canada Inc) | Varies + ACM | 325 mg to 500 mg |

| Alka Seltzer products (Bayer Inc, Canada) | Calcium carbonate + citric acid + potassium bicarbonate + sodium bicarbonate + ACM | 250 mg to 325 mg |

| Anacin, Anacin-3 (Wyeth Consumer Healthcare Inc, Canada) | Varies + ACM | 80 mg to 500 mg, 100 mg/mL, 160 mg/5 mL |

| Arthritis Foundation Aspirin-Free (USA) | Varies + ACM | 500 mg |

| Benadryl Allergy/Cold Tablets (Pfizer Canada Inc) | Varies + ACM | 500 mg |

| Comtrex products (Bristol-Myers Squibb, USA) | Varies + ACM | 325 mg to 1000 mg, 500 mg/5 mL, 500 mg/15 mL, 1000 mg/5mL |

| Drixoral products (Schering Canada Inc) | Varies + ACM | 325 mg to 500 mg |

| Excedrin migraine products (Novartis Consumer Health Canada Inc) | Acetylsalicylic acid + caffeine + ACM | 250 mg to 500 mg |

| Goody’s Extra Strength Headache Powder and products (GlaxoSmithKline Inc, USA) | Acetylsalicylic acid + caffeine + ACM | 130 mg to 500 mg, 260 mg per powder paper |

| Liquiprin (Lee Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline Inc, USA) | ACM | 80 mg/0.8 mL, 80 mg/1.66 mL, 80 mg/2.5 mL |

| Midrin (Women First Healthcare, USA) | Isometheptene + dichloralphenazone + ACM | 325 mg |

| Nyquil (Procter & Gamble Inc, Canada) | Varies + dichloralphenazone + ACM | 250 mg, 167 mg/5 mL, 1000 mg/packet, 1000 mg/30 mL |

| Pamprin (Chattem Inc, USA) | Pamabrom + pyrilamine + diphenhydramine + ACM | 250 mg to 500 mg, 650 mg/packet |

| Panadol (GlaxoSmithKline Inc, Canada) | Caffeine + ACM | 80 mg to 500 mg, 60 mg/0.6 mL, 80 mg/0.5 mL |

| Sine-Aid Sinus Medicine (McNeil Pharmaceuticals,USA) | Pseudophedrine + ACM | 500 mg |

| Sinutab products (Pfizer Canada Inc) | Pseudophedrine + ACM | 325 mg to 500 mg, 1000 mg/oz |

| Sominex Pain Relief Formula (GlaxoSmithKline Inc, USA) | Diphenhydramine + ACM | 500 mg |

| St Joseph’s Aspirin Free Products (McNeil-PPC Inc, USA) | Phenylpropanolamine + ACM | 80 mg to 500 mg, 60 mg/0.6 mL, 80 mg/0.8 mL, 80 mg/2.5 mL, 120 mg/5 mL, 160 mg/5 mL |

| Sudafed Sinus products (Pfizer Canada Inc) | Varies + ACM | 325 mg to 500 mg |

| Tempra products (Mead Johnson Nutritionals, Canada) | ACM | 80 mg, 160 mg/5 mL |

| Theraflu products (Novartis Consumer Health Inc, USA) | Varies + ACM | 325 mg to 650 mg, 650 mg to 1000 mg/packet |

| Tylenol products (McNeil Consumer Healthcare, Canada) | Varies + ACM | 325 mg to 650 mg, 250 mg/5 mL, 650 mg/30 mL, 650 mg to 1000 mg/packet, 1000 mg/30 mL |

| Vanquish products (Bayer Healthcare Corp, USA) | Acetylsalicylic acid + caffeine + ACM | 194 mg |

A multitude of prescription narcotic analgesics also have ACM added to them to improve their efficacy. Some of these products may contain as much as 750 mg of ACM per tablet such as Vicodin ES (Abbott Laboratories, USA) (Table 2). Because narcotic products can lead to addiction, the potential for untoward hepatotoxicity in patients with a history of substance abuse is even greater. Furthermore, because many patients with acute medical conditions may have impaired oral intake, it is possible that hepatic glutathione depletion may lower the threshold for ACM hepatotoxicity (16). Lastly, patients with a history of alcohol abuse may be at greater risk for ACM hepatotoxicity, particularly if they take excessive doses for a hangover immediately after stopping alcohol (17). A provocative hypothesis that individuals who develop hepatotoxicity at low doses of daily ACM consumption (ie, 4 g/day to 6 g/day) may actually be experiencing ‘idiosyncratic’ hepatotoxicity due to genetic alterations in drug-metabolizing enzymes or other environmental cofactors has recently been raised (18). The US ALFSG plans to explore the potential role of genetic polymorphisms in drug toxification, detoxification and regenerative pathways in cases of both intentional and nonintentional ACM overdose.

TABLE 2.

Prescription narcotic analgesics that contain acetaminophen (ACM)

| Trade name | Components | ACM dose (mg/tablet) |

|---|---|---|

| Anexsia (Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, USA) | Hydrocodone + ACM | 325 mg to 660 mg |

| Capital with Codeine Suspension (Carnrick Laboratories Inc, USA) | Codeine + ACM | 120 mg/5 mL |

| Darvocet-N50 (Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals Inc, USA) | Propoxyphene + ACM | 325 mg |

| Darvocet-N100 (Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals Inc, USA) | Propoxyphene + ACM | 650 mg |

| Darvocet-A500 (Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals Inc, USA) | Propoxyphene + ACM | 500 mg |

| Endocet (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Canada) | Oxycodone + ACM | 325 mg to 650 mg |

| Esgic Plus (Mikart Inc, USA) | Butalbital + caffeine + ACM | 500 mg |

| Fioricet (Watson Pharmaceuticals Inc, USA) | Butalbital + caffeine + ACM | 325 mg |

| Fioricet with Codeine (Watson Pharmaceuticals Inc, USA) | Butalbital + caffeine + codeine + ACM | 325 mg |

| Lorcet (Forest Laboratories Inc, USA) | Hydrocodone + ACM | 325 mg to 750 mg, 500 mg/15 mL |

| Lortab (Whitby Pharmaceuticals, USA) | Hydrocodone + ACM | 325 mg to 500 mg, 500 mg/15 mL |

| Maxidone (Watson Laboratories Inc, USA) | Hydrocodone + ACM | 750 mg |

| Norco (Watson Laboratories Inc, USA | Hydrocodone + ACM | 325 mg |

| Panadol #3 and #4 (GlaxoSmithKline, Canada) | Codeine + ACM | 300 mg |

| Percocet (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Canada), Oxycet (Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, USA) | Oxycodone + ACM | 325 mg to 650 mg |

| Phenaphen with codeine (AH Robbins Co, USA) | Codeine + ACM | 325 mg to 650 mg |

| Roxicet (Roxane Laboratories Inc, USA) | Oxycodone + ACM | 325 mg to 500 mg, 325 mg/5 mL |

| Sedapap (Merz Pharmaceuticals, USA) | Butalbital + ACM | 650 mg |

| Talacen (Sanofi Winthrop Inc, USA) | Pentazocine + ACM | 650 mg |

| Tylenol with Codeine #2, #3 and #4 (Janssen-Ortho Inc, Canada) | Codeine + ACM | 300 mg |

| Tylox (Ortho-McNeil Inc, USA) | Oxycodone + ACM | 500 mg |

| Ultracet (Ortho-McNeil Inc, USA) | Tramadol + ACM | 325 mg |

| Vicodin (Abbott Laboratories, USA) | Hydrocodone + ACM | 500 mg |

| Vicodin ES (Abbott Laboratories, USA) | Hydrocodone + ACM | 750 mg |

| Vicodin HP (Abbott Laboratories, USA) | Hydrocodone + ACM | 660 mg |

| Wygesic (Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, USA) | Propoxyphene + ACM | 650 mg |

| Zydone (Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc, USA) | Hydrocodone + ACM | 400 mg |

The US Food and Drug Administration recently reviewed our data and related information on ACM hepatotoxicity at an advisory board meeting in 2002 (19). The only action taken was the insertion on the package labelling regarding the hazards of concomitant alcohol and ACM ingestion. Overall, many of us think more could and should still be done to apprise the general public and practitioners of the potential hazards of excessive ACM ingestion.

PA: What about patients with pre-existing liver disease and daily ACM dosing?

RJF: Many of us actually recommend ACM as the analgesic of choice for patients with liver disease due to concerns of the adverse effects of acetylsalicylic acid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients with cirrhosis or portal hypertension (ie, gastrointestinal bleeding or renal toxicity). Although patients with established liver disease and cirrhosis have intact glucuronidation and other detoxification pathways, most experts recommend less than 4 g/day. In my clinical practice, I conservatively advise a maximum of 2 g/day of ACM in patients with cirrhosis and up to 4 g/day in patients with milder liver disease. Ironically, many of my patients with mild liver disease are afraid to take any ACM-based analgesic as a result of the advice of their local medical providers or what they have read on the internet. I think we (ie, the gastroenterology/hepatology community) need to do a better job of educating our fellow physicians and patients that ACM is the preferred pain reliever for patients with liver disease but that the total daily dose ingested should be monitored.

PA: Does monitoring liver enzymes in patients on daily ACM predict hepatotoxicity?

RJF: In light of recent comparative studies, several medical organizations now recommend ACM as the first-line agent for millions of patients with osteoarthritis due to its comparable efficacy, lower cost and generally favourable safety profile compared with NSAIDs and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors (20,21). In these large multicentre studies, patients were treated for three months with 4 g/day of ACM, and none of them developed liver toxicity. Extrapolating from that experience, I do not think that there is any role for liver enzyme monitoring in patients receiving therapeutic doses of ACM chronically. In fact, regular liver biochemistry monitoring is also not of any proven benefit for other potentially hepatotoxic drugs such as isoniazid and statins. In the ALFSG, over 93% of patients who developed non-intentional ACM-related ALF were consuming excessive doses of ACM and that is the most important risk factor.

PA: Can supplementation with glutathione be a helpful strategy?

RJF: Hepatotoxicity develops when excessive amounts of the highly reactive intermediate, NAPQI, are generated in the liver. The normal means to detoxify NAPQI is via glutathione transsulfuration. Theoretically, when hepatic glutathione stores are depleted from prolonged fasting, one may be more susceptible to ACM toxicity but confirmatory human data are lacking. Nonetheless, some experts have proposed incorporating a precursor of glutathione into ACM-containing products (22,23). For example, S-adenosylmethionine is converted in vivo to glutathione and this product is commercially available in multiple over-the-counter products as an antioxidant. Therefore, one could add a fixed dose of S-adenosylmethionine to each tablet of ACM and theoretically reduce the risk of toxicity if an excessive amount of ACM were ingested. However, this would require extensive reformulation of many ACM-containing products and there are no prospective data demonstrating the efficacy of this approach. Hence, I do not think we can support this approach currently, but I find the idea intriguing.

Other proposed strategies to reduce the incidence of ACM hepatotoxicity include restrictions on the amount of ACM that one can purchase at a pharmacy or supermarket. In the US, you can buy unlimited bulk quantities of ACM for a few dollars and some of the larger bottles (ie, 500 tablets of 500 mg) contain enough tablets that could be toxic to over 20 adults. In the United Kingdom, where the annual incidence of ACM overdose is nearly 10 times higher than other western countries, the government took several steps in 1998 to reduce the incidence of intentional ACM overdose (24). In addition to limiting the quantity of ACM dispensed at pharmacies, they also required blister packaging of ACM-containing products and instituted labelling changes as well. Although this was not popular with the pharmaceutical industry and the sales of ACM products initially declined, the morbidity and mortality from ACM overdose significantly declined, with a 22% reduction in suicidal deaths from ACM and a 30% reduction in the number of patients requiring liver transplantation (24). Similar measures could be undertaken in the US and other developed countries where ACM is a leading cause of ALF.

PA: There seems to be problems with most analgesics in liver disease patients. Acetylsalicylic acid and NSAIDs can cause bleeding and affect renal function. Narcotics are addictive. Many hospitals and physicians are still recommending ACM as the safest analgesic in patients with liver disease, including inpatients. Do you see this changing after your study?

RJF: The short answer is no, not really. In our prospective study, none of the patients were hospitalized when they developed nonintentional ACM overdose. Therefore, I do not think that the primary problem lies in the excessive use of ACM in hospitals. However, there are reports (25) demonstrating how inpatient ACM orders can be misinterpreted by nursing staff. Patients with liver disease are frequently hospitalized and may require antipyretics for fevers or blood product transfusions, and as it turns out, fever and infections, as well as chronic liver disease, can lead to a reduction in oxidative metabolism and cytochrome P450 expression. One prospective study (26) of children with high fevers receiving therapeutic doses of ACM in the hospital demonstrated no evidence of ACM-protein adduct formation. Therefore, as long as the total daily dose remains within the recommended guidelines I think we should be okay in the hospital setting.

However, I would point out some other interesting data from the ALFSG regarding the use of ACM in patients with severe acute liver injury. A paper by Davern et al (27) has recently looked at the diagnostic utility of ACM-cysteine adducts as a biomarker for ACM hepatotoxicity. The bottom line is that serum ACM-cysteine adducts were present in all tested patients with ACM-induced hepatotoxicity and this assay may prove useful in cases of diagnostic uncertainity. However, 20% of patients with known HAV- or HBV-related ALF also had detectable ACM-cysteine adducts and these patients tended to have higher serum ALT levels and poorer outcomes compared with the adduct-negative group. This suggests that these patients may have been receiving potentially toxic doses of ACM for their prodromal symptoms of fever and malaise. In addition, 20% of the indeterminate ALF cases had detectable adducts and these patients also had higher serum ALT and lower bilirubin levels compared with the others. This suggests that they may have been misdiagnosed as ACM overdose cases or that ACM may have been a cofactor in their illness. The latter speculation raises the question as to whether we should administer N-acetylcysteine to all indeterminate ALF patients with high serum aminotransferase levels, because the adduct assay is not currently commercially available. I would suggest that we need to study this further before changing our clinical practice. In addition, a recent meta-analysis showed no demonstrable benefit of N-acetylcysteine for non-ACM-related liver injury (28). And as you know, we are currently addressing this issue in our ongoing double-blind randomized controlled trial of intravenous N-acetylcysteine versus placebo in non-ACM-induced ALF that we hope to complete soon.

PA: So where do we go from here?

RJF: Overall, I think that ACM is a highly effective and generally safe analgesic when used in recommended doses. Unfortunately, ACM has found its way into so many over-the-counter and prescription products that we have allowed the general public to become exposed to this potentially hepatotoxic compound in various insidious and unforeseen circumstances. Furthermore, because these products are marketed as being safer than alternative analgesics such as acetylsalicylic acid and NSAIDs, the general public may unwittingly consume higher doses than recommended for an acute illness and develop inadvertent hepatotoxicity. I actually think that if ACM were introduced today as a new drug, not only would it be denied over-the-counter dispensing status, but it may not even be approvable as a prescription drug due to its known dose-dependent hepatotoxicity. But because the drug has been around for so many years with a tremendous worldwide prescribing experience, manufacturers contend that it should remain freely available in the marketplace with little or no restrictions. One of the limitations with the ALFSG observational data is knowing the denominator of users of the over-the-counter and prescription narcotic-ACM products but once we know that what will be an acceptable rate of avoidable hepatotoxicity?

To prevent future cases of inadvertent ACM hepatotoxicity, I think several actions should be considered. At a minimum, all prescription narcotic-ACM congeners should state on the dispensing label and product the amount of ACM included in each tablet and the maximum daily allowable dose, and patients should receive simple written instructions regarding other products that may put them at risk of inadvertent overdose. Alternatively, if additional studies demonstrate a high-rate of nonintentional ACM-related ALF due to prescription narcotic-ACM congeners, the amount of ACM in these products should either be restricted or completely eliminated (ie, do no harm). Regulations for over-the-counter products are a more difficult issue. While you could propose to limit dispensing of these products to, say, 30 tablets per bottle, that may inconvenience millions of people in legitimate need of these medications as well as increase consumer costs. However, the experience in the UK has been very favourable and preventing additional deaths or liver transplantation due to this avoidable circumstance is worthwhile and likely cost-effective. At a minimum, I think labelling changes that include prominent listing of ACM on these products, the maximum number of tablets allowable, restricting the amount of ACM in each therapeutic dose to, say, 300 mg, and greater regulatory oversight to provide more balanced marketing claims is reasonable. Finally, a substantial public health initiative to educate patients and physicians of this avoidable cause of potentially lethal ALF is warranted in light of its increasing incidence.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiodt FV, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakela J, Mosley JW, Edwards VM, Govindarajan S, Alpert E. A double-blinded randomized trial of hydrocortisone in acute hepatic failure. The Acute Hepatic Failure Study Group. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1223–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01307513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritt DJ, Whelan G, Werner DJ, Eigenbrodt EH, Schenker S, Combes B. Acute hepatic necrosis with stupor or coma. An analysis of thirty-one patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1969;48:151–72. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umemura T, Tanaka E, Ostapowicz G, et al. Investigation of SEN virus infection in patients with cryptogenic acute liver failure, hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia, or acute and chronic non-A-E hepatitis. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1545–52. doi: 10.1086/379216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee WM, Brown KE, Young NS, et al. Brief report: No evidence of parvovirus B19 or hepatitis E virus as causes of acute liver failure. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-9061-5. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wai CT, Fontana RJ, Polson J, et al. Clinical outcome and virological characteristics of hepatitis B-related acute liver failure in the United States. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:192–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaquero J, Fontana RJ, Larson AM, et al. Complications and use of intracranial pressure monitoring in patients with acute liver failure and severe encephalopathy. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1581–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, et al. Acute Liver Failure Study Group Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: Results of a United States multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1364–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.20948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman HJ, Maddrey WC. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) hepatotoxicity with regular intake of alcohol: Analysis of instances of therapeutic misadventure. Hepatology. 1995;22:767–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiodt FV, Rochling FA, Casey DL, Lee WM. Acetaminophen toxicity in an urban county hospital. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1112–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710163371602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lovitz TL, Klein-Schwartz W, White S, et al. 2000 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:337–95. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.25272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborne ZP, Bryant SM. Patients discharged with a prescription for acetaminophen-containing narcotic analgesics do not receive appropriate written instructions. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:48–50. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2003.50038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smilkstein MJ, Knapp GL, Kulig KW, Rumack BH. Efficacy of oral N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose. Analysis of the national multicenter study (1976 to 1985) N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1557–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812153192401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rumack BH. Acetaminophen misconceptions. Hepatology. 2004;40:10–5. doi: 10.1002/hep.20300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeff LB, Lindsay KL, Bacon BR, Kresina TF, Hoofnagle JH. Complementary and alternative medicine in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;34:595–603. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitcomb DC, Block GD. Association of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity with fasting and ethanol use. JAMA. 1994;272:1845–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520230055038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slattery JT, Nelson SD, Thummel KE. The complex interaction between ethanol and acetaminophen. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60:241–6. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplowitz N. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: What do we know, what don't we know, and what do we do next? Hepatology. 2004;40:23–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.20312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WM. Acetaminophen and the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group: Lowering the risks of hepatic failure. Hepatology. 2004;40:6–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikles CJ, Yelland M, Del Mar C, Wilkinson D. The role of paracetamol in chronic pain: An evidence-based approach. Am J Ther. 2005;12:80–91. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200501000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wegman A, van der Windt D, van Tulder M, Stalman W, de Vries T. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or acetaminophen for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee? A systematic review of evidence and guidelines. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:344–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Grady JG. Paracetamol hepatotoxicity: How to prevent. J R Soc Med. 1997;90:368–70. doi: 10.1177/014107689709000703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song Z, McClain CJ, Chen T. S-Adenosylmethionine protects against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Pharmacology. 2004;71:199–208. doi: 10.1159/000078086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawton K, Simkin S, Deeks J, et al. UK legislation on analgesic packs: Before and after study of long term effect on poisonings. BMJ. 2004;329:1076. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38253.572581.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb SA, Henry RL. Paracetamol pro re nata orders: An audit. J Paeditr Child Health. 2004;40:213–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James LP, Wilson JT, Simar R, et al. Evaluation of occult acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in hospitalized children receiving acetaminophen. Pediatric Pharmacology Research Unit Network. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2001;40:243–8. doi: 10.1177/000992280104000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davern TJ, II, James LP, Hinson JA, et al. Measurement of serum acetaminophen-protein adducts in patients with acute liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:687–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sklar GE, Subramaniam M. Acetylcysteine treatment for non-acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:498–500. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]