Abstract

A 52-year-old woman developed severe watery diarrhea, weight loss, anemia and hypoalbuminemia. A localized colon cancer was detected. Subsequently, extensive collagenous mucosal involvement of the small and large intestine was discovered. After resection of the colon cancer, her symptoms resolved. In addition, resolution of the inflammatory process occurred, including the subepithelial collagen deposits. Despite extensive small and large intestinal involvement, both clinical and histological resolution of collagenous inflammatory disease was evident. Collagenous enterocolitis is an inflammatory process that may represent a distinctive and reversible paraneoplastic phenomenon.

Keywords: Collagenous colitis; Collagenous enterocolitis; Collagenous sprue; Colon cancer, Paraneoplastic syndrome

Abstract

Une femme de 52 ans présentait de graves diarrhées liquides, une perte de poids, de l’anémie et de l’hypoalbuminémie. Un cancer du côlon circonscrit a été décelé. On a ensuite découvert une importante atteinte de la muqueuse collagénique de l’intestin grêle et du gros intestin. Après résection du cancer du côlon, les symptômes ont disparu. De plus, on a observé une résolution du processus inflammatoire, y compris les dépôts de collagène sous-épithélial. Malgré une importante atteinte de l’intestin grêle et du gros intestin, tant la résolution clinique que la résolution histologique de la maladie inflammatoire collagénique étaient évidentes. L’entérocolite collagénique est un processus inflammatoire qui peut constituer un phénomène paranéoplasique distinct et réversible.

Collagenous mucosal disease in both the small and large intestine has been recognized as a cause of diarrhea, particularly in middle-aged and elderly women (1). Recent Swedish registry data indicate that detection rates for collagenous colitis and ulcerative colitis in the elderly are similar (2). Usually, with colonic disease, watery diarrhea is common. With small bowel disease, however, malabsorption of different nutrients may occur. In most collagenous sprue cases reported to date, severe and ongoing malabsorption, weight loss and, often, a fatal outcome have been recorded. The precise pathogenetic mechanisms involved in these disorders remain poorly understood and still require elucidation.

This etiologically complex process is defined by distinct subepithelial collagen deposits. An intimate link with other ‘autoimmune disorders’ (eg, celiac disease) (3) or prior treatment with specific drugs (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and lansoprazole) (4,5) has been noted. Genetic factors may be important (6) and some may evolve from a pathologically different disorder, lymphocytic colitis (7). Lymphoma may occur with these collagenous disorders (8,9), but risk of other neoplasms (eg, colon cancer) is not increased (10). In the present patient, extensive collagenous disease resolved after resection of a concomitant colon cancer. This suggests a distinctive pathological process that, in some patients, may be a paraneoplastic phenomenon.

CASE PRESENTATION

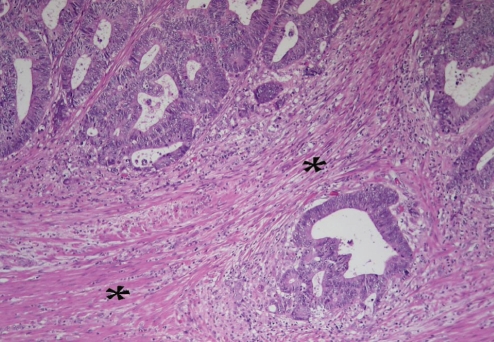

A 52-year-old woman developed a four-to six-month illness characterized by progressive malaise, loss of appetite, diarrhea up to 15 to 20 watery, nonbloody stools daily, weight loss of 15 kg and lower limb edema. She had no history of prior medical disorders, medication use or familial history of intestinal disease. Initial investigations in a rural community hospital, including studies for an infectious cause, were negative. A barium study of her small intestine was normal, but a colonoscopy demonstrated a 2 cm adenocarcinoma. In April 2004, a right hemicolectomy was performed for a moderately differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma, but none of 32 lymph nodes were involved (T2N0) (Figure 1). Because of the diarrhea, a full-thickness small intestinal biopsy was performed but reported to be normal.

Figure 1).

Moderately differentiated colonic adenocarcinoma infiltrating into smooth muscle (*) of the muscularis propria

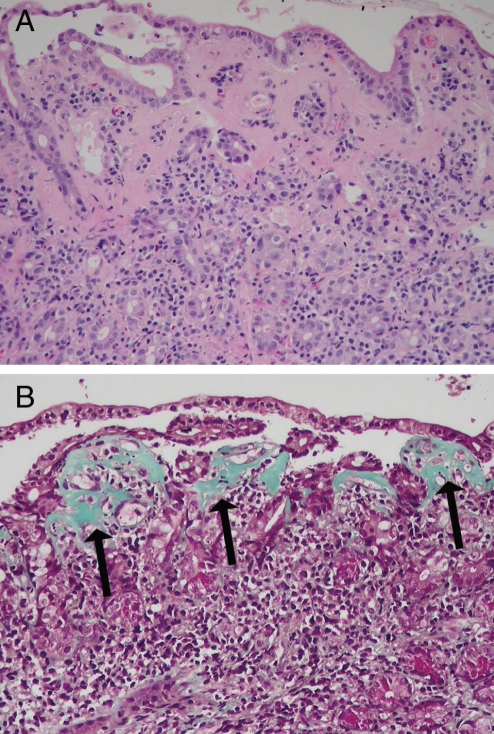

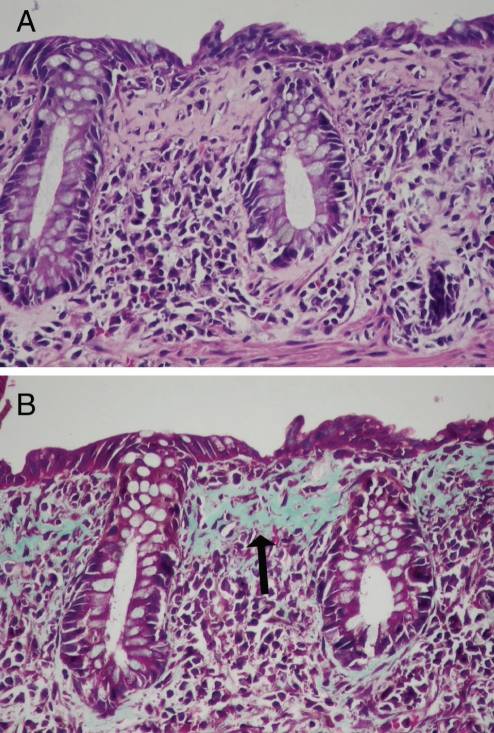

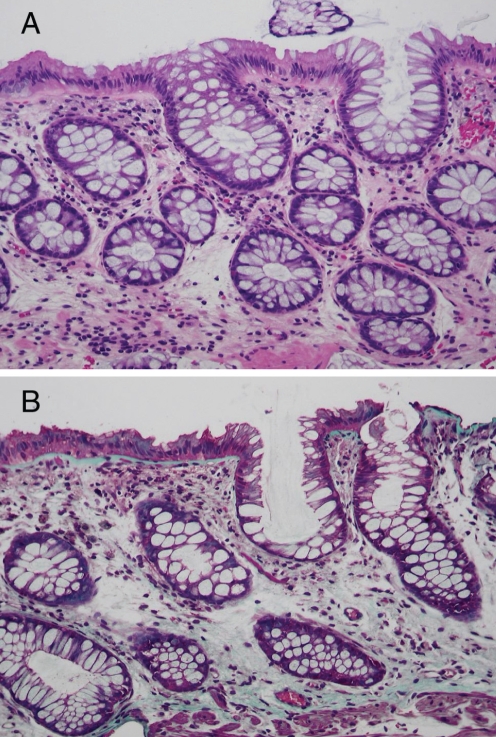

Postoperatively, her diarrhea persisted, so further studies were undertaken. Bloodwork showed an anemia (hemoglobin 118 g/L) with hypoalbuminemia (26 g/L). Other serum studies were normal including liver chemistry tests, electrolytes, magnesium, calcium, phosphate, carotene, immunoglobulins, cholesterol, triglycerides, gastrin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. Serum antibodies for gliadin and tissue transglutaminase were negative. Fecal cultures for bacteria, parasites and Clostridium difficile were negative. Abdominal and pelvic ultrasonography as well as computed tomography revealed surgical clips from her prior colonic resection. Endoscopic studies were normal, including the ileocolic anastomosis. However, an endoscopic biopsy of the duodenum showed partial villous atrophy with marked thickening of the subepithelial collagenous layer (Figure 2A and 2B). There was a mild lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the lamina propria and mild epithelial lymphocytosis. Endoscopic biopsies of the colon showed similar, but slightly less prominent, thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer (Figure 3A and 3B). Collagenous sprue and collagenous colitis were diagnosed.

Figure 2).

Collagenous enterocolitis. Duodenal mucosa (A) showing markedly thickened subepithelial collagen layer (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100). Trichrome stain of duodenal mucosa (B) highlights the thickened collagen layer (arrows) (Mallory’s trichrome, original magnification ×100)

Figure 3).

Collagenous enterocolitis. Colonic mucosa (A) showing markedly thickened subepithelial collagen layer (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×100). Trichrome stain of colonic mucosa (B) highlights the thickened collagen layer (arrow) (Mallory’s trichrome, original magnification ×100)

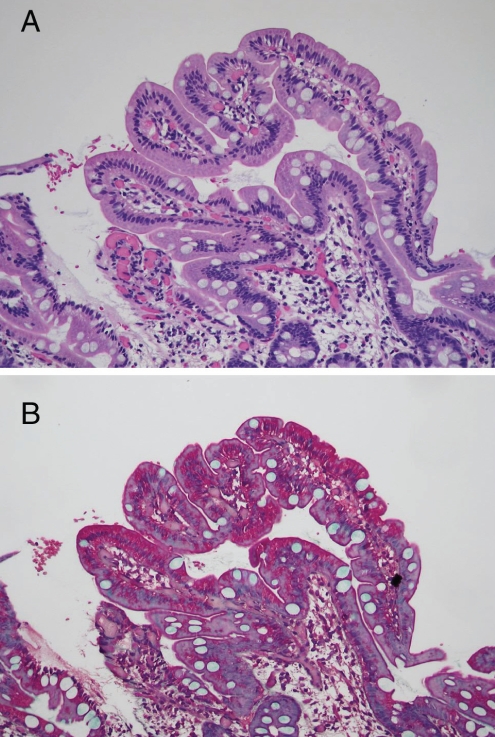

Treatments with a gluten-free diet and oral 5-aminosalicylates (4 g daily) were not effective, but a four-week course of oral budesonide controlled ileal release 9 mg daily was initially associated with reduced diarrhea. In July 2004, she moved to British Columbia to a meditation centre on Saltspring Island. She had persistent diarrhea and bilateral lower limb edema, but over the next three to four months, this completely resolved without medication on a normal diet. In October 2004, she was re-evaluated. She had regained all of her lost weight. She had no diarrhea and, except for surgical scars, her physical examination was normal. Bloodwork was normal, including her hemogram (hemoglobin 125 g/L) and serum albumin (37 g/L). Her tissue transglutaminase serology was normal. Endoscopic evaluation of her upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts and biopsies of the stomach, duodenum and colon were normal (Figures 4A, 4B, 5A and 5B).

Figure 4).

Normal duodenal mucosa with return of the subepithelial collagen layer to normal. A Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100; B Mallory’s trichrome, original magnification ×100

Figure 5).

Normal colonic mucosa with return of the subepithelial collagen layer to normal. A Hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100; B Mallory’s trichrome, original magnification ×100

In March 2005, all prior pathological sections were reviewed, including sections from her colonic resection. The carcinoma was confirmed with negative lymph nodes; however, subepithelial collagen deposits were detected in both the resected colon and the original full-thickness small intestinal biopsy. Through June 2005, she has remained well with no recurrent diarrhea.

DISCUSSION

Collagenous sprue and colitis are pathologically distinct disorders involving the small and large intestine (1). The hallmark of both disorders is thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer. The diseases are usually seen in middle-aged to elderly women and present with diarrhea and, often, weight loss. In addition, with extensive small bowel involvement, severe malabsorption and evidence of protein loss may develop. Rarely, concomitant involvement of both gastric and intestinal sites has been recorded (11,12). The etiology and pathogenesis still require elucidation, although inherited and other factors may play a role (3–7).

In the patient recorded here, extensive collagenous involvement of the small and large intestine was associated with a colon cancer. Given the localized nature of the neoplastic lesion, her symptoms appeared inappropriately severe to be directly attributed to the maligancy. Following cancer resection, the clinical and pathological features of her concomitant small and large intestinal diseases dramatically and completely resolved. Although budesonide may have played a role in partially improving her symptoms associated with this extensive intestinal inflammatory process, it is unlikely to have been responsible for the complete histological resolution of her disease. Detailed histological studies in several placebo-controlled trials have shown that budesonide treatment in collagenous colitis improves the thickening of the subepithelial collagen deposits and decreases the inflammation within the lamina propria, but does not produce complete histological resolution of the disease process (13–15). In the present report, extensive involvement of the colon as well as the small intestine was completely reversed and normalized, including resolution of the collagen deposits.

While concurrent collagenous colitis and colon cancer have been previously recorded elsewhere (16), an increased colon cancer risk in collagenous colitis has not been defined to date, including an extensive registry series of 117 collagenous colitis patients followed for a mean of seven years (10). However, there are prior historical reports of apparent resolution of collagenous colitis following treatment of a malignant disorder. In one, resolution of collagenous colitis was recorded after chemotherapeutic treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (17). In the other, collagenous colitis refractory to medical treatment improved after a subtotal colectomy with a Brooke ileostomy for a colon carcinoma (18). In the present patient, collagenous disease, extensively present in both the small intestine and colon, resolved completely and has not recurred, suggesting that these collagen deposits represented a pathologically defined paraneoplastic phenomenon. Recent reports have implicated a hormone-related or immune-mediated pathogenesis for paraneoplastic phenomena in colon cancer (19–24). Further definition of the precise mechanism involved in the mucosal deposition of collagen associated with malignant disorders is needed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freeman HJ. Collagenous mucosal inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:338–50. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olesen M, Eriksson S, Bohr J, Jarnerot G, Tysk C. Microscopic colitis: A common diarrheal disease. An epidemiological study in Orebro, Sweden, 1993-1198. Gut. 2004;53:346–50. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.014431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman HJ. Collagenous colitis as the presenting feature of biopsy-defined celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:664–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000135363.12794.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giardiello FM, Hansen FC, III, Lazenby AJ, et al. Collagenous colitis in setting of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:257–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01536772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson RD, Lestina LS, Bensen SP, Toor A, Maheshwari Y, Ratcliffe NR. Lansoprazole-associated microscopic colitis: A case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2908–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Tilburg AJ, Lam HG, Sledenrijk CA, et al. Familial occurrence of collagenous colitis. A report of two families. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:279–85. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH, Giardiello FM, Jessurun J, Bayliss TM. Lymphocytic (microscopic) colitis: A comparative histopathologic study, with particular reference to collagenous colitis. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:18–28. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards DB. Collagenous colitis and histiocytic lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:260–1. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-3-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouyaya F, Michenet P, Gargot D, Breteau N, Buzacoux J, Legoux JL. Lymphocytic colitis, followed by collagenous colitis, associated with mycosis fundoides-type-T-cell lymphoma. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1993;17:976–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan JL, Tersmette AC, Offerhaus GJ, Gruber SB, Bayless TM, Giardiello FM. Cancer risk in collagenous colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:40–3. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulimood AB, Ramakrishna BS, Mathan MM. Collagenous gastritis and collagenous colitis: A report with sequential histological and ultrastructural findings. Gut. 1999;44:881–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castellano VM, Munoz MT, Colina F, Nevado M, Casis B, Solis-Herruzo JA. Collagenous gastrobulbitis and collagenous colitis. Case report and review of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:632–8. doi: 10.1080/003655299750026128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baert F, Schmit A, D’Haens G, et al. Budesonide in collagenous colitis: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial with histologic follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:20–5. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miehlke S, Heymer P, Bethke B, et al. Budesonide treatment for collagenous colitis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:978–84. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonderup OK, Hansen JB, Birket-Smith L, Vestergaard V, Teglbjaerg R, Fallingborg J. Budesonide treatment for collagenous colitis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial with morphometric analysis. Gut. 2003;52:248–51. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardiner GW, Goldberg R, Currie D, Murray D. Colonic carcinoma associated with an abnormal collagen table. Collagenous colitis. Cancer. 1984;54:2973–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841215)54:12<2973::aid-cncr2820541227>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Werf SD, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Bronkhorst FB, Werre JM. Chemotherapy responsive collagenous colitis in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease: A possible paraneoplastic phenomenon. Neth J Med. 1987;31:228–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alikhan M, Cummings OW, Rex D. Subtotal colectomy in a patient with collagenous colitis associated with colonic carcinoma and systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1213–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson JT, Paschold EJ, Levine EA. Paraneoplastic hypercalcemia in a patient with adenosquamous cancer of the colon. Am Surg. 2001;67:585–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stummvoll GH, Aringer M, Machold KP, Smolen JS, Raderer M. Cancer polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis as a first sign of hidden neoplasms. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:40–4. doi: 10.1080/030097401750065319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pantalone D, Muscas GC, Tings T, et al. Peripheral paraneoplastic neuropathy, an uncommon clinical onset of sigmoid cancer. Tumori. 2002;88:347–9. doi: 10.1177/030089160208800420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsukamoto T, Mochizuki R, Mochizuki H, et al. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration and limbic encephalitis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the colon. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:713–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.6.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peek R, Dijkstra BG, Meek B, Kuijpers RW. Autoantibodies to photoreceptor membrane proteins and outer plexiform layer in patients with cancer-associated retinopathy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128:498–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobson DM, Adamus G. Retinal anti-bipolar cell antibodies in a patient with paraneoplastic retinopathy and colon carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:806–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]