Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

The survival of treated, noncirrhotic patients with hereditary hemochromatosis is similar to that of the general population. Less is known about the outcome of cirrhotic hereditary hemochromatosis patients. The present study evaluated the survival of patients with hereditary hemochromatosis and cirrhosis.

METHODS:

From an established hereditary hemochromatosis database, all cirrhotic patients diagnosed from January 1972 to August 2004 were identified. Factors associated with survival were determined using univariate and multivariate regression. Survival differences were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier life table method.

RESULTS:

Ninety-five patients were identified. Sixty patients had genetic testing, 52 patients (87%) were C282Y homozygotes. Median follow-up was 9.2 years (range 0 to 30 years). Nineteen patients (20%) developed hepatocellular carcinoma, one of whom was still living following transplantation. Cumulative survival for all patients was 88% at one year, 69% at five years and 56% at 20 years. Factors associated with death on multivariate analysis included advanced Child-Pugh score and hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were older at the time of diagnosis of cirrhosis (mean age 61 and 54.6 years, respectively; P=0.03). The mean age at the time of diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was 70 years (range 48 to 79 years). No other differences were found between the groups.

CONCLUSIONS:

Patients with hereditary hemochromatosis and cirrhosis are at significant risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma. These patients are older when diagnosed with carcinoma and may have poorer survival following transplantation than patients with other causes of liver disease. Early diagnosis and treatment of hereditary hemochromatosis by preventing the development of cirrhosis may reduce the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the future.

Keywords: Hemochromatosis, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Iron overload

Abstract

OBJECTIFS :

La survie des patients non cirrhotiques atteints d’hémochromatose héréditaire traités est similaire à celle de l’ensemble de la population. On n’en sait pas autant sur l’issue des patients cirrhotiques atteints d’hémochromatose héréditaire. La présente étude visait à évaluer la survie de ces patients.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

À partir d’une base de données établie de l’hémochromatose héréditaire, tous les patients cirrhotiques diagnostiqués entre janvier 1972 et août 2004 ont été repérés. Les facteurs associés à la survie ont été déterminés au moyen d’une régression univariée et multivariée. Les différences de survie ont été évaluées d’après la méthode de table de survie de Kaplan-Meier.

RÉSULTATS :

Quatre-vingt-quinze patients ont été repérés. Soixante avaient subi des tests génétiques, et 52 (87 %) étaient homozygotes C282Y. Le suivi médian était de 9,2 ans (fourchette de 0 à 30 ans). Dixneuf patients (20 %) ont développé un carcinome hépatocellulaire, et un vivait toujours après une transplantation. La survie cumulative de tous les patients était de 88 % au bout d’un an, de 69 % au bout de cinq ans et de 56 % au bout de 20 ans. À l’analyse multivariée, les facteurs associés au décès incluaient un indice de Child-Pugh avancé et un carcinome hépatocellulaire. Les patients atteints d’un carcinome hépatocellulaire étaient plus âgés au moment du diagnostic de cirrhose (âge moyen de 61 ans et de 54,6 ans, respectivement; P=0,03). L’âge moyen au diagnostic de carcinome hépatocellulaire était de 70 ans (fourchette de 48 à 79 ans). Aucune autre différence n’a été constatée entre les groupes.

CONCLUSIONS :

Les patients cirrhotiques atteints d’hémochromatose héréditaire sont très vulnérables à l’apparition d’un carcinome hépatocellulaire. Ces patients sont plus âgés au diagnostic de carcinome et peuvent présenter une survie moindre après la transplantation que les patients atteints d’une maladie hépatique d’autre origine. Un diagnostic précoce et le traitement de l’hémochromatose héréditaire par la prévention de l’apparition d’une cirrhose pourraient peut-être réduire l’incidence de carcinome hépatocellulaire.

Hereditary hemochromatosis, which results predominantly from mutations in the HFE gene, is one of the most common autosomal recessive inherited diseases of humans (1). In Canada, approximately one in 227 Caucasian individuals are homozygous for the C282Y mutation of the HFE gene (2,3).

Hereditary hemochromatosis is characterized phenotypically by an inappropriately high rate of intestinal iron absorption (4). Iron is subsequently deposited in many tissues, most notably the liver, where it can eventually lead to cirrhosis. Hepatocellular carcinoma complicating cirrhosis caused by hereditary hemochromatosis is well recognized (5–7).

The survival of adequately treated, noncirrhotic patients with hereditary hemochromatosis is similar to that of the general population (8). However, less is known about the outcome of hereditary hemochromatosis patients with cirrhosis. In the present study, we evaluated the long-term outcome of patients with hereditary hemochromatosis and cirrhosis, particularly those with hepatocellular carcinoma.

METHODS

Patients

From an established database of hereditary hemochromatosis patients, all cirrhotic patients diagnosed from January 1972 to August 2004 were identified. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was based on clinical findings in 47 patients and histological findings in 48 patients. A clinical diagnosis of cirrhosis was established by an experienced hepatologist, and was based on a combination of physical examination and biochemical findings, as well as features of hepatic decompensation (ascites, portal hypertension and hepatic encephalopathy). The presence of histological cirrhosis was established by a pathologist familiar with chronic liver disease and iron overload. Cirrhosis was defined as widespread destruction of normal liver structure by fibrosis and the formation of regenerative nodules. Patients with other medical conditions known to be associated with iron overload, such as hemolytic anemia and history of multiple transfusions, were excluded. There were no patients with chronic hepatitis B or C in this group. Regarding alcohol intake, 17 patients, two with hepatocellular carcinoma, had a history of current or previous regular use, which was defined as greater than 20 g per day for men and 10 g per day for women.

Patient outcomes were determined from evaluation of medical records; communication with the patient’s gastroenterologist, primary care physician or, in some cases, the patient him-or herself; or family members. Factors associated with survival duration were determined using univariate and multivariate regression analyses. The following data were recorded at the time of diagnosis of cirrhosis: age, sex, serum ferritin level, transferrin saturation, aspartate aminotransferase level, alanine aminotransferase albumin level, bilirubin level, creatinine level and international normalized ratio. Data from liver biopsy included hepatic iron concentration (normal less than 36 μmol/g of dry liver weight) and hepatic iron index (hepatic iron concentration/age in years). Patients were considered diabetic if they required long-term treatment with insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents to control hyperglycemia. The presence of arthritis was determined by history and physical examination. Total iron removed during phlebotomy, Child-Pugh score, the presence of encephalopathy, ascites and history of regular alcohol use were also included in this analysis. All patients in the present series diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma were referred for surgical opinion.

Genetic studies

Among patients who underwent genetic testing for hereditary hemochromatosis after 1997, analysis of the C282Y mutation was performed by polymerase chain reaction amplification before restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, as has been previously described (9).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by logistic regression using the MedCalc software package (version 6.0, Mariakerke, Belgium). Values were considered significant at P<0.05. The independent effect of significant variables from univariate analysis (P<0.05) was assessed using multivariate regression analysis. Survival differences were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier life table method (Winstat 3.0, Kalmia, USA).

RESULTS

Patients

The main clinical and biological data of the patients are given in Table 1. The mean age of all patients was 57 years (range 28 to 82 years). The mean age at the time of diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was 70 years (range 48 to 79 years). Fourteen patients (15%) were women and 81 (85%) were men. Median follow-up duration for the present study was 9.2 years (range 0 to 30 years).

TABLE 1.

Main clinical and biochemical data of 95 cirrhotic hereditary hemochromatosis patients

| Demographics | All patients (n=95) | Non-HCC patients (n=76) | HCC patients (n=19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis of cirrhosis, years (range) | 57 (28–82) | 56 (28–82) | 61 (47–74) |

| Age at death, years (range) | 66 (40–93) | 65 (40–93) | 69 (48–79) |

| Sex, n (men/women) | 81/14 | 64/12 | 17/2 |

| Ferritin, μg/L (range) | 2303 (285–12,024) | 2647 (285–12,024) | 2893 (531–5376) |

| Transferrin saturation, % (range) | 85 (20–105) | 82 (21–105) | 79 (20–100) |

| AST, U/L (range) | 66 (17–746) | 83 (17–746) | 73 (16–213) |

| ALT, U/L (range) | 57 (6–475) | 76 (6–475) | 89 (19–354) |

| Bilirubin, μmol/L (range) | 16 (4–158) | 26 (4–158) | 27 (8–80) |

| Albumin, g/L (range) | 39 (21–47) | 38 (21–47) | 33 (21–42) |

| Creatinine, μmol/L (range) | 80 (50–166) | 84 (50–166) | 93 (70–129) |

| INR (range) | 1.1 (0.9–2.0) | 1.1 (1–1.9) | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) |

| HIC, μmol/L (range) | 369 (13–814) | 329 (13–772) | 458 (89–814) |

| HII, HIC/age ratio (range) | 5.8 (0.26–17.9) | 7 (0.3–18) | 7 (1.5–12) |

| Diabetes (yes/no) | 38/57 | 26/50 | 12/7 |

| Arthritis (yes/no) | 32/63 | 25/51 | 7/12 |

| Iron removed during phlebotomy, g (range) | 11 (1–32) | 13 (1–32) | 11 (2–25) |

| Child-Pugh score (range) | 6 (5–12) | 6 (5–12) | 7 (5–10) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (yes/no) | 10/85 | 8/68 | 2/17 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 17/78 | 12/64 | 5/14 |

| Regular alcohol use (yes/no) | 17/78 | 15/61 | 2/17 |

ALT Alanine aminotransferase; AST Aspartate aminotransferase; HCC Hepatocellular carcinoma; HIC Hepatic iron concentration; HII Hepatic iron index; INR International normalized ratio

Regarding the diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis after 1997, 60 patients underwent genetic testing and of these, 52 patients (87%) were C282Y homozygotes. In the remaining cases, a diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis was made based on liver biopsy with a hepatic index greater than 1.9 and was supported by pedigree studies.

Of 95 patients, 19 (20%) had a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma while 76 (80%) were free of hepatocellular carcinoma. In all cases, hereditary hemochromatosis was diagnosed before the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. The diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was confirmed by histological findings on percutaneous biopsy, surgical resection or autopsy. Of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, only one was alive at the end of follow-up, having undergone orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) for this indication. Ten patients underwent regular screening with ultrasound and alpha-fetoprotein. Four patients had hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosed during screening. Alpha-fetoprotein level was only minimally elevated (16 μ/L) in one patient who successfully underwent OLT and was living at the time of the present study. Alpha-fetoprotein was significantly elevated in the remaining patients (386 μg/L to 2109 μg/L). A second patient was offered chemoembolization and declined. The remaining two patients were too ill for surgery or other treatment modalities. Of those not screened for hepatocellular carcinoma, two patients had incidentally diagnosed tumours. One patient underwent three sessions of percutaneous ethanol injection and survived 18 months following diagnosis. The second patient received chemoembolization and survived 25 months. Both patients eventually died secondary to tumour progression.

Univariate analysis

Clinical and laboratory features were evaluated to determine which, if any, correlated with patient survival. Univariate analysis was performed for each variable (using logistic regression for continuous variables and linear regression for frequency data). Factors significantly associated with death on univariate analysis included male sex, ferritin level, transferrin saturation, alanine aminotransferase level, bilirubin level, creatinine level, international normalized ratio, hepatic iron index, Child-Pugh score and the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (P<0.05).

Multivariate analysis

The independent effects of factors found to be significant in univariate analysis were assessed by multivariate analysis (stepwise linear regression). Using the multiple regression model, the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (P=0.0273) and Child-Pugh score (P=0.00025) were found to be associated with shorter survival duration. The parameters from this analysis are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Linear regression analysis

| I | Xi | β | SE | T | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Constant | 83.79351 | |||

| 1 | Child-Pugh score | −2.61941 | 0.83635 | −3.132 | 0.0025 |

| 2 | Hepatocellular carcinoma* | 7.67350 | 3.40534 | 2.253 | 0.0273 |

Equation of prediction: Y predicted (probability of shortened survival) = P (shortened survival [X1, X2]) = (β0 + ∑βiXi) = (83.79351 – 2.61941 Child-Pugh score + 7.67350 hepatocellular carcinoma [0;1]).

Absence of hepatocellular carcinoma = 0; presence of hepatocellular carcinoma = 1

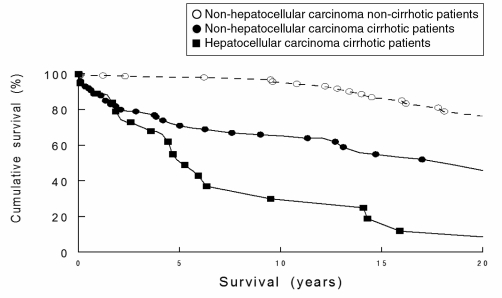

Kaplan-Meier survival curve

The survival curve of 76 nonhepatocellular carcinoma patients was compared with 19 hepatocellular carcinoma-affected patients (Figure 1). The rate of survival was lower in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (P=0.0193, log rank test). Cumulative survival for all patients was 88% at one year, 68% at five years, 63% at 10 years and 55% at 20 years.

Figure 1).

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the nonhepatocellular carcinoma noncirrhotic, nonhepatocellular carcinoma cirrhotic and hepatocellular carcinoma cirrhotic patients

DISCUSSION

In the present retrospective study of the long-term follow-up of patients with hereditary hemochromatosis and cirrhosis, a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was established in 19 of 95 patients (20%). The prevalence at the authors’ centre is in keeping with the literature, where the published incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis ranges from 12.4% to 45% (10–12). It is possible that this is a slight underestimation of the true prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma because not all patients were screened for hepatocellular carcinoma or underwent autopsy, at which time small tumours may have been discovered with careful hepatic sectioning. Also, because the authors’ centre is a referral centre for patients with hemochromatosis, a referral bias cannot be excluded.

Patients who undergo iron depletion therapy before the development of cirrhosis have a survival rate comparable with the general population (5,13). The development of genetic testing for hemochromatosis has led to earlier diagnosis in patients with possible iron overload and has led to screening of family members, allowing the diagnosis to be made at a presymptomatic stage (14–16). The widespread availability of genetic testing may lead to early diagnosis and treatment. This could, in the future, lead to a decreasing incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis.

Before 1995, patients at the authors’ centre did not receive routine surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus, the majority of patients in the current study were not screened. In recent years, serial ultrasound and alpha-fetoprotein measurements have been widely adopted as surveillance measures. However, this practice remains controversial because definite evidence is lacking that show that surveillance improves patient outcomes (17–19). Had each patient undergone regular, biannual ultrasounds and alpha-fetoprotein measurements, a total of 2894 investigations would have been performed, resulting in significant cost (20,21).

Before the publication of the Milan criteria (22) in 1996, few patients at the authors’ centre underwent transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma. The majority of tumours in the present study (13 of 19) were diagnosed in patients before this time and would not have been transplantated. As well, although there is no absolute age when transplantation is contraindicated, with increasing age, the risks associated with transplantation begin to exceed an acceptable level (23–25). It has also been shown that older transplant recipients, particularly those older than 60 years, have poorer long-term post-transplant survival. Malignancy accounts for the majority of deaths in this patient group (26,27). An acceptable upper limit for age at many centres, including the authors’, is approximately 70 years. Among the hepatocellular carcinoma patients in the present study, 11 of 18 would have been excluded from consideration for transplantation as a result of advanced age at the time of diagnosis. In addition, with an average wait for transplant of two to three years, many of the remaining patients who would have been considered candidates may have become ineligible. It is also likely that in some cases during this waiting period, tumour progression may have resulted in the patient becoming ineligible for transplant.

In contrast with hemochromatosis, the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with viral hepatitis appears to occur at a younger age. A mean age of 63 years for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma has been reported in patients with hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis (28,29). Therefore, early diagnosis in this group of patients may allow for more definitive treatment of lesions with transplantation or hepatic resection in those who are candidates. Despite concerns regarding recurrent infection, many appropriately selected patients with viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma generally do well following liver transplantation. Patients with hereditary hemochromatosis and iron overload have been shown to have poorer survival following liver transplant (30,31). This outcome is not explained solely by the concomitant presence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Increased rates of infection and late cardiac complications have been found to be the most common causes of post-transplant deaths in hereditary hemochromatosis patients (32,33). One- and five-year post-transplant survival rates of only 64% and 34% have been documented in hereditary hemochromatosis patients (34). These are significantly worse than the generally accepted rates of 80% and 70% seen for most other causes of chronic liver disease (35).

SUMMARY

Hepatocellular carcinoma occurs in approximately 20% of hemochromatosis patients with cirrhosis and is one of the most common causes of death. The role of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in these patients needs to be further evaluated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feder JN, Gnirke A, Thomas W, et al. A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Nat Genet. 1996;13:399–408. doi: 10.1038/ng0896-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams PC. Population screening for haemochromatosis. Gut. 2000;46:301–3. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams PC, Reboussin DM, Barton JC, et al. Hemochromatosis and iron-overload screening of in a racially diverse population. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1769–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming RE, Sly WS. Mechanisms of iron accumulation in hereditary hemochromatosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:663–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.155838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fargion S, Fracanzani AL, Piperno A, et al. Prognostic factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in genetic hemochromatosis. Hepatology. 1994;20:1426–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840200608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niederau C, Fischer R, Sonnenberg A, Stremmel W, Trampisch HJ, Strohmeyer G. Survival and causes of death in cirrhotic and in noncirrhotic patients with primary hemochromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1256–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511143132004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiniakos G, Williams R. Cirrhotic process, liver cell carcinoma and extrahepatic tumors in idiopathic hemochromatosis. Study of 71 patients treated with venesection therapy. Appl Pathol. 1988;6:128–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niederau C, Strohmeyer G, Stremmel W. Epidemiology, clinical spectrum and prognosis of hemochromatosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;356:293–302. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2554-7_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams PC, Halliday JW, Powell LW. Early diagnosis and treatment of hemochromatosis. Adv Intern Med. 1989;34:111–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellerbrand C, Poppl A, Hartmann A, Scholmerich J, Lock G. HFE C282Y heterozygosity in hepatocellular carcinoma: Evidence for an increased prevalence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:279–84. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strohmeyer G, Niederau C, Stremmel W. Survival and causes of death in hemochromatosis. Observations in 163 patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;526:245–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb55510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fargion S, Mandelli C, Piperno A, et al. Survival and prognostic factors in 212 Italian patients with genetic hemochromatosis. Hepatology. 1992;15:655–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams PC, Speechley M, Kertesz AE. Long-term survival analysis in hereditary hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:368–72. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90013-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards CQ, Cartwright GE, Skolnick MH, Amos DB. Homozygosity for hemochromatosis: Clinical manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:519–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-4-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galhenage SP, Viiala CH, Olynyk JK. Screening for hemochromatosis: Patients with liver disease, families, and populations. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004;6:44–51. doi: 10.1007/s11894-004-0025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCune CA, Ravine D, Worwood M, Jackson HA, Evans HM, Hutton D. Screening for hereditary haemochromatosis within families and beyond. Lancet. 2003;362:1897–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14963-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larcos G, Sorokopud H, Berry G, Farrell GC. Sonographic screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis: An evaluation. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:433–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.2.9694470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Bisceglie AM. Issues in screening and surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S104–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velazquez RF, Rodriguez M, Navascues CA, et al. Prospective analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2003;37:520–7. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolondi L, Sofia S, Siringo S, et al. Surveillance programme of cirrhotic patients for early diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A cost effectiveness analysis. Gut. 2001;48:251–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniele B, Bencivenga A, Megna AS, Tinessa V. Alpha-fetoprotein and ultrasonography screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:108–12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett-Guerrero E, Feierman DE, Barclay GR, et al. Preoperative and intraoperative predictors of postoperative morbidity, poor graft function, and early rejection in 190 patients undergoing liver transplantation. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1177–83. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.10.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin GL, Sasaki AW, Zaman A, et al. Comparative analysis of outcome following liver transplantation in US veterans. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:788–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desai NM, Mange KC, Crawford MD, et al. Predicting outcome after liver transplantation: Utility of the model for end-stage liver disease and a newly derived discrimination function. Transplantation. 2004;77:99–106. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000101009.91516.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrero JI, Lucena JF, Quiroga J, et al. Liver transplant recipients older than 60 years have lower survival and higher incidence of malignancy. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1407–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins BH, Pirsch JD, Becker YT, et al. Long-term results of liver transplantation in older patients 60 years of age and older. Transplantation. 2000;70:780–3. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, et al. Morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type C: A retrospective follow-up study of 384 patients. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:463–72. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9024300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fattovich G, Pantalena M, Zagni I, Realdi G, Schalm SW, Christensen E. Effect of hepatitis B and C virus infections on the natural history of compensated cirrhosis: A cohort study of 297 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2886–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawford DH, Fletcher LM, Hubscher SG, et al. Patient and graft survival after liver transplantation for hereditary hemochromatosis: Implications for pathogenesis. Hepatology. 2004;39:1655–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.20242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kowdley KV, Hassanein T, Kaur S, et al. Primary liver cancer and survival in patients undergoing liver transplantation for hemochromatosis. Liver Transpl Surg. 1995;1:237–41. doi: 10.1002/lt.500010408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tung BY, Farrell FJ, McCashland TM, et al. Long-term follow up after liver transplantation in patients with hepatic iron overload. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:369–74. doi: 10.1002/lt.500050503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brandhagen DJ. Liver transplantation for hereditary hemochromatosis. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:663–72. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.25359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kowdley KV, Brandhagen DJ, Gish RG, et al. Survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatic iron overload: The national hemochromatosis transplant registry. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kilpe VE, Krakauer H, Wren RE. An analysis of liver transplant experience from 37 transplant centers as reported to Medicare. Transplantation. 1993;56:554–61. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199309000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]