Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Acute esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis. Guidelines have been published in 1997; however, variability in the acute management and prevention of EVB rebleeding may occur.

METHODS:

Gastroenterologists in the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan were sent a self-reporting questionnaire.

RESULTS:

The response rate was 70.4% (86 of 122). Intravenous octreotide was recommended by 93% for EVB patients but the duration was variable. The preferred timing for endoscopy in suspected acute EVB was within 12 h in 75.6% of respondents and within 24 h in 24.6% of respondents. Most (52.3%) gastroenterologists do not routinely use antibiotic prophylaxis in acute EVB patients. The preferred duration of antibiotic therapy was less than three days (35.7%), three to seven days (44.6%), seven to 10 days (10.7%) and throughout hospitalization (8.9%). Methods of secondary prophylaxis included repeat endoscopic therapy (93%) and beta-blocker therapy (84.9%). Most gastroenterologists (80.2%) routinely attempted to titrate beta-blockers to a heart rate of 55 beats/min or a 25% reduction from baseline. The most common form of secondary prophylaxis was a combination of endoscopic and pharmacological therapy (70.9%).

CONCLUSIONS:

Variability exists in some areas of EVB treatment, especially in areas for which evidence was lacking at the time of the last guideline publication. Gastroenterologists varied in the use of prophylactic antibiotics for acute EVB. More gastroenterologists used combination secondary prophylaxis in the form of band ligation eradication and beta-blocker therapy rather than either treatment alone. Future guidelines may be needed to address these practice differences.

Keywords: Antibiotics, Practice, Prophylaxis, Rebleeding, Survey, Variceal bleeding

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’hémorragie aiguë des varices œsophagiennes (HVO) est une importante cause de morbidité et de mortalité chez les patients atteints d’une cirrhose hépatique. Des lignes directrices ont été publiées en 1997, mais il peut exister une certaine variabilité dans la prise en charge aiguë et la prévention de nouvelles hémorragies.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Un questionnaire a été envoyé aux gastroentérologues des provinces de la Colombie-Britannique, de l’Alberta, du Manitoba et de la Saskatchewan.

RÉSULTATS :

Le taux de réponse s’élevait à 70,4 % (86 sur 122). De l’octréotide intraveineux était recommandé par 93 % des gastroentérologues pour les patients atteints d’une HVO, mais la durée du traitement variait. Le moment de procéder à une endoscopie dans les cas de HVO aiguë présumée était favorisé dans un délai de 12 heures pour 75,6 % des répondants et dans un délai de 24 h pour 24,6 % des répondants. La plupart (52,3 %) des gastroentérologues n’utilisent pas systématiquement une prophylaxie antibiotique chez les patients atteints d’une HVO aiguë. La durée préconisée de l’antibiothérapie était inférieure à trois jours (35,7 %), de trois à sept jours (44,6 %), de sept à dix jours (10,7 %) et tout au long de l’hospitalisation (8,9 %). Les modes de prophylaxie secondaire consistaient à répéter le traitement endoscopique (93 %) et aux bétabloquants (84,9 %). La plupart des gastroentérologues (80,2 %) tentaient systématiquement de titrer les bétabloquants à un rythme cardiaque de 55 battements/minute ou une réduction de 25 % par rapport au début du traitement. La forme la plus courante de prophylaxie secondaire était une combinaison de thérapie endoscopique et pharmacologique (70,9 %).

CONCLUSIONS :

Il existe une certaine variabilité dans certains aspects du traitement de l’HVO, surtout dans les domaines qui ne s’associaient pas à des données probantes au moment de la publication des dernières lignes directrices. Les gastroentérologues n’utilisaient pas tous les mêmes antibiotiques prophylactiques pour traiter la HVO aiguë. Plus de gastroentérologues utilisaient une polyprophylaxie secondaire sous forme d’éradication par ligature élastique et de thérapie aux bétabloquants plutôt que d’un traitement seul. De nouvelles lignes directrices pourraient être nécessaires pour traiter de ces différences de pratique.

Approximately 30% of patients with cirrhosis develop esophageal varices and one-third of these patients experience esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB) (1,2). There is considerable morbidity with EVB and the mortality rate with each episode is up to 30% (3). Once EVB has occurred, the rate of recurrence is up to 60% if no further intervention is offered (3).

The last clinical practice guidelines by the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) on the management of variceal bleeding were published in 1997 (4). However, the timing, duration and dosing of specific medical therapies in EVB patients have not been recommended. Recently, further therapies have been suggested to be efficacious in the management of acute EVB. The routine use of antibiotics has been recently shown to reduce infection and mortality in acute EVB patients (5,6). Pharmacotherapy or repeat esophageal band ligation has already been recommended in the prevention of recurrent bleeding but there is also evidence that combination therapy may improve rebleeding outcomes (4,7,8). It is unknown how or whether recent recommendations are being routinely applied in EVB patients. There are limited data on the current practices of gastroenterologists with EVB patients. The purpose of the present study was to determine the practice patterns of gastroenterologists in the acute management and secondary prevention of EVB.

METHODS

A list of practicing gastroenterologists was obtained from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Questionnaires were mailed in May 2005. The two-page, self-reporting survey consisted of two categories: demographic data and questions on the physician’s approach to the management of initial EVB. The survey package included a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study with an explanation of anonymity and a stamped returning envelope. Questionnaires were labelled numerically and anonymously for tracking purposes. Surveys were collected by an assistant with no access to survey results. Surveys were remailed four weeks later to initial nonresponders.

The results were collected into a spreadsheet database. Demographic data and questionnaire answers were recorded numerically. The proportion of responses were calculated and expressed as percentages. The limited sample size precluded statistical subgroup analysis.

The study was approved by the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

A total of 90 of 122 gastroenterologists responded to the survey. Four surveys were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires. The final response rate was 70.4% (86 of 122) (Table 1). The response rates according to provinces were: British Columbia 73.1% (38 of 52), Alberta 72% (36 of 50), Manitoba 76.9% (10 of 13) and Saskatchewan 28.6% (two of seven).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of gastroenterologists in a study examining management and prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding (EVB) (n=86)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Province | |

| Alberta | 36 (41.9) |

| British Columbia | 38 (44.2) |

| Manitoba | 10 (11.6) |

| Saskatchewan | 2 (2.3) |

| Hepatology focus | 24 (27.9) |

| Routinely manage patients with acute EVB | 75 (87.2) |

| Routinely manage patients with previous EVB | 82 (95.3) |

| Teaching hospital | 52 (60.4) |

| Community hospital | 34 (39.6) |

The proportion of gastroenterologists who reported a focus in hepatology was 27.9%. Most performed endoscopy (94.1%). Most routinely managed patients with acute EVB (87.2%) and followed patients who had previous EVB episodes (95.3%). Sixty per cent of respondents practiced at a teaching hospital, while 40% practiced at a community hospital (Table 1).

Acute EVB

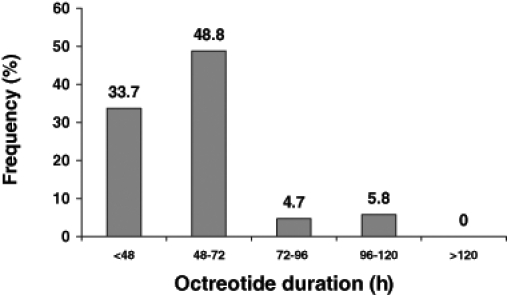

During acute EVB, 93% of gastroenterologists routinely used intravenous (IV) octreotide. However, the duration for which IV octreotide infusion was used for the control of EVB was variable: 33.7% for 24 h to 48 h, 48.8% for 48 h to 72 h, 4.7% for 72 h to 96 h, 5.8% for 96 h to 120 h and 0% for more than 120 h (Figure 1). Endoscopic therapy was recommended within 12 h of presentation by 75.6% and within 24 h by 24.6%.

Figure 1).

Octreotide infusion duration during acute esophageal variceal bleeding routinely used by gastroenterologists (n=86)

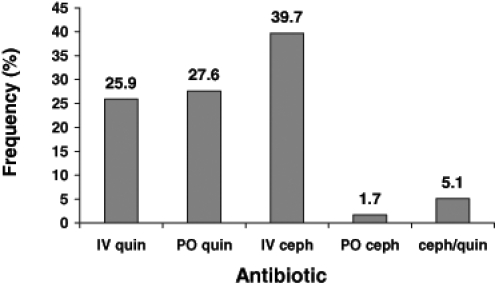

The proportion of gastroenterologists who routinely used antibiotics for infection prophylaxis during acute EVB was 47.7%. The antibiotic used was variable: 39.7% used IV cephalosporin, 25.9% used IV fluoroquinolone, 27.6% used oral fluoroquinolone, 5.1% used a combination of cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone and 1.7% used oral cephalosporin (Figure 2). Of those who used prophylactic antibiotics, 64.2% started pre-endoscopy and 35.8% started postendoscopy. The duration of antibiotic use varied: 35.7% used antibiotics for less than three days, 44.6% for three to seven days, 10.7% for seven to 10 days and 8.9% throughout hospitalization.

Figure 2).

Antibiotics preferred by gastroenterologists who routinely use antibiotic prophylaxis in acute esophageal variceal bleeding (n=41). Ceph Third-generation cephalosporin; IV Intravenous; PO Orally; Quin Quinolones

Prevention of esophageal variceal rebleeding

The forms of secondary prophylaxis used by gastroenterologists to prevent EVB rebleeding after an initial event included repeat endoscopic therapy only (23.3%), pharmacological therapy only (5.8%) and endoscopic and/or pharmacological therapy (76.9%). Of those who performed repeat endoscopy, 93% performed it routinely and 19.5% recommended it within one week, 17.1% by two weeks, 43.9% by four weeks, 15.9% by eight weeks and 3.7% depended on hospital wait list time. Repeat endoscopic therapy was performed by 95.3% until varices were eradicated.

Pharmacotherapy with beta-blockers was routinely used by 83.7% of the gastroenterologists. Nadolol (46.8%) was the first choice, followed by propranolol 28.6%, metoprolol 3.9%, either nadolol or propranolol 22.6% and either propranolol or metoprolol 1.3%. When beta-blockers were used, 80.2% of respondents routinely attempted to titrate the dose to a heart rate of 55 beats/min or to a 25% reduction from baseline. Nitrates alone were not recommended by any gastroenterologist, and only 2.3% used nitrates in combination with beta-blockers. When pharmacotherapy was used, 74% started therapy in a hospital as opposed to as an outpatient. The use of combination endoscopic therapy and pharmacotherapy simultaneously for secondary prophylaxis of EVB was recommended by 70.9% of gastroenterologists. Reported barriers to pharmacotherapy were patient intolerance (77.9%), noncompliance (53.4%) and insufficient evidence (7.0%). Although 22.1% of gastroenterologists claimed no barriers to performing endoscopic secondary prophylaxis, 77.9% reported the following barriers: patient noncompliance (51.2%), lack of resources (30.2%) and insufficient evidence (9.3%).

DISCUSSION

EVB is a significant cause of hospitalization and mortality among patients with cirrhosis. Practice guidelines were published in 1997 on the management of EVB by the ACG (4). However, practice patterns and adherence to the ACG guidelines have not been recently assessed. In addition, further studies have been published in the literature that may influence the current practice of gastroenterologists. The present study surveyed gastroenterologists and found that there was variability in certain aspects of their approach to the management of acute EVB and secondary prophylaxis.

During acute EVB, surveyed gastroenterologists routinely used IV octreotide when available. However, the duration of octreotide use varied, with one-third of gastroenterologists suggesting up to 48 h and one-half up to 72 h. Although no recommendations on the duration of octreotide have been published, studies that have shown benefit in rebleeding rates used an infusion rate of five days (9,10). Interestingly, only 5.8% of gastroenterologists routinely infused octreotide for five days. Factors for lower duration of use may include medication cost, earlier discharge from hospital and anecdotal experience that shorter duration of use may not lead to adverse outcomes.

In acute EVB patients, endoscopic band ligation therapy is effective and stops bleeding in 90% of cases (4,8,11,12). Suspected EVB is usually considered an urgent indication for endoscopy, but the optimal timing is unknown. More than 50% of patients continue bleeding without immediate therapy. The high risk for complications in EVB patients appears to be appreciated among respondents in this survey because the majority (75.6%) recommended endoscopy within 12 h of presentation with suspected EVB.

Cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding are at an increased risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and other infections not specific to patients with liver disease (13–15). Prophylactic treatment in cirrhotic patients with GI bleeding (independent of the presence or absence of ascites) has been associated with reduced rates of infections and even mortality (6,14,15). Although antibiotic prophylaxis was not addressed in the last ACG guidelines, recommendations have since been published on the routine use of antibiotics, particularly with fluoroquinolones (6). However, a recent single-centre, Canadian, retrospective study (16) reported that less than one-quarter of cirrhotic patients with GI bleeding admitted to hospital received prophylactic antibiotics. Similarly, we found that only less than one-half (47.7%) of all gastroenterologists surveyed reported routinely using antibiotic prophylaxis. In addition, although the reported evidence has mostly involved fluoroquinolones (6,14,15,17–19), only 53.5% used oral or IV fluoroquinolones, while 41.4% used IV cephalosporins. Cases of SBP have been traditionally treated with third-generation cephalosporins (5), and the high rate of cephalosporin use may be due to its traditional use as a first-line therapy in SBP. We note that antibiotic use in cirrhotic patients with GI bleeding prevents infections other than SBP, such as bacteremia, pneumonia and urinary tract infections (4,8,11,12). The lack of consensus on antibiotic prophylaxis indicates that further recommendations are needed. In addition, further studies looking at the efficacy of cephalosporins in EVB are warranted before it is routinely used for EVB.

Once a patient has had an episode of EVB, the rate of recurrence without further treatment is up to 60% (3). Endoscopic eradication of varices may lower the rate of recurrent bleeding to 25% to 30% in one year (8). Nonselective beta-blocker therapy (nadolol or propranolol) has been shown to lower recurrent bleeding rates to 44% (20). Either endoscopic therapy or pharmacotherapy (ie, beta-blockers) has been recommended by the ACG as a method of reducing recurrent bleeding (4). Accordingly, we found that endoscopic eradication and beta-blockers were routinely used as secondary prophylaxis by 95.3% and 83.7% of surveyed gastroenterologists, respectively. The combination of band ligation eradication plus a beta-blocker has a potential role, but currently, only limited evidence is available (7,21). Recently, the Portal Hypertension Report of the Baveno IV Consensus Workshop (22) concluded that combination therapy is likely the best treatment but more trials are needed. Despite the paucity of studies in this area, the present study found that majority of gastroenterologists (76.7%) attempted to use combination therapy to prevent variceal rebleeding. However, the proportion of patients actually undergoing combination prophylaxis may not be that high for a variety of reasons. The reported barriers to using beta-blockers were mainly patient intolerance and noncompliance. The barriers to endoscopic eradication therapy were mainly patient noncompliance and a lack of resources, but over 20% claimed no barriers at all. Although the majority of gastroenterologists appear to be advocating combination secondary prophylaxis, further studies in this area are needed to justify this practice.

Overall, the regional gastroenterologists approach to EVB is consistent with the last published guideline. However, in the treatment of acute EVB, variability exists in the duration of octreotide treatment and the use of antibiotic prophylaxis. In the prevention of rebleeding, beta-blockers are being routinely recommended and the majority advocates for combination therapy with endoscopic eradication and beta-blockers. Future guidelines on EVB are needed to address these issues that were not previously recommended.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by an unrestricted research grant from Janssen-Ortho Canada Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.The North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices Prediction of first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:983–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gores GJ, Wiesner RH, Disckson ER, Zinsmeister AR, Jorgensen RA, Langworthy A. Prospective evaluation of esophageal varices in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1552–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:800–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grace ND. Diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1081–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimola A, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A consensus document. J Hepatol. 2000;32:142–53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard B, Grange JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1655–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, et al. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus nadolol and sucralfate compared with ligation alone for the prevention of variceal rebleeding: A prospective, randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:461–5. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharara AI, Rockey DC. Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:669–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Besson I, Ingrand P, Person B, et al. Sclerotherapy with or without octreotide for acute variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:555–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung JY, Chung SM, Yung MY, et al. Prospective randomized study of effect of octreotide on rebleeding from oesophageal varices after endoscopic ligation. Lancet. 1995;346:1666–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laine L, el-Newihi HM, Migikovsky B, Sloane R, Garcia F. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-1-199307010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA, et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1527–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206043262304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard B, Cadranel JF, Valla D, Escolano S, Jarlier V, Opolon P. Prognostic significance of bacterial infection in bleeding cirrhotic patients: A prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1828–34. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh WJ, Lin HC, Hwang SJ, et al. The effect of ciprofloxacin in the prevention of bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis after upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:962–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauwels A, Mostefa-Kara N, Debenes B, et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis after gastrointestinal hemorrhage for cirrhotic patients with a high risk of infection. Hepatology. 1996;24:802–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilbur K, Sidhu K. Antimicrobial therapy in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:607–11. doi: 10.1155/2005/759360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soriano G, Guarner C, Tomas A, et al. Norfloxacin prevents bacterial infection in cirrhotics with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1267–72. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blaise M, Pateron D, Trinchet JC, Levacher S, Beaugrand M, Pourriat JL. Systemic antibiotic therapy prevents bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1996;20:34–8. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soares-Weiser K, Brezis M, Tur-Kaspa R, Paul M, Yahav J, Leibovici L. Antibiotic prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic inpatients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:193–200. doi: 10.1080/00365520310000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: A meta-analytic review. Hepatology. 1995;22:332–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840220145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de la Pena J, Brullet E, Sanchez-Hernadez E, et al. Variceal ligation plus nadolol compared with ligation for prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding: A multicenter trial. Hepatology. 2005;41:572–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005;43:167–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]