Abstract

Structurally diverse chemotherapeutic and chemopreventive drugs, including camptothecin, doxorubicin, sanguinarine, and others, were found to cause covalent crosslinking of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) trimers in mammalian cells exposed to fluorescent light. This PCNA damage was caused by both nuclear and cytoplasmically localizing drugs. For some drugs, the PCNA crosslinking was evident even with very brief exposures to laboratory room lighting. In the absence of drugs, there was no detectable covalent crosslinking of PCNA trimers. Other proteins were photo-crosslinked to PCNA at much lower levels, including crosslinking of additional PCNA to the PCNA trimer. The proteins photo-crosslinked to PCNA did not vary with cell type or drug. PCNA was not crosslinked to itself or to other proteins by superoxide, hydrogen peroxide or hydroxyl radicals, but hydrogen peroxide caused mono-ubiquitination of PCNA. Quenching of PCNA photo-crosslinking by histidine, and enhancement by deuterium oxide, suggest a role for singlet oxygen in the crosslinking. SV40 large T antigen hexamers were also efficiently covalently photo-crosslinked by drugs and light. Photodynamic crosslinking of nuclear proteins by cytoplasmically localizing drugs, together with other evidence, argues that these drugs may reach the nucleoplasm in amounts sufficient to photodamage important chromosomal enzymes. The covalent crosslinking of PCNA trimers provides an extremely sensitive biomarker for photodynamic damage. The damage to PCNA and large T antigen raises the possibility that DNA damage signaling and repair mechanisms may be compromised when cells treated with antineoplastic drugs are exposed to visible light.

Keywords: Large T antigen, Photodynamic, PCNA, Proliferating cell nuclear antigen, Protein damage, Protein crosslinks

1. Introduction

Light excites photodynamic drugs to a triplet state that can transfer energy to molecular oxygen, converting it from its triplet ground state to a highly reactive singlet state (type II mechanism), or can react directly with other molecules to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals (type I mechanism) [1–3]. Singlet oxygen, the species responsible for most photodynamic damage [4], is rapidly inactivated by interactions with water and other molecules so that it reaches ineffective concentrations before it can diffuse far from its source. The short diffusion distance, a small fraction of a mammalian cell diameter [3], has given rise to the idea of targeted photodynamic damage to intracellular sites of photodynamic drug localization [1–3]. Targets of photodynamic damage include cellular organelles such as cell membranes, lysosomes, and mitochondria as well as biomolecules such as DNA and proteins. Covalent modification of proteins by radiation, ROS, or xenobiotics, including covalent protein crosslinking, is protein damage [5–7].

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was first identified as a nuclear antigen seen only in the S-phase of the cell cycle [8]. It was later identified as a processivity factor for DNA polymerase delta, both in DNA replication and in DNA repair [9]. PCNA functions as a homotrimer, with three PCNA monomers arranged in a ring that encircles the DNA strand [10]. This allows it to "clamp" DNA polymerase delta to the template strand to increase processivity [11]. The binding between the PCNA subunits in the circular trimer is non-covalent, so only PCNA momomers are detected under denaturing conditions, such as SDS gel electrophoresis. Treatment of cells or cell extracts with protein crosslinking agents can covalently crosslink the subunits of the PCNA trimer so that it migrates as a high molecular weight PCNA form on SDS gels [12]. Crosslinking studies have also suggested that two PCNA trimers may be arranged in pairs in the cell [13]. The PCNA ring is assembled onto DNA by replication factor C (RFC), a clamp loader [14]. In addition to being involved in DNA replication and DNA excision repair, PCNA is involved in DNA lesion bypass during DNA replication. When mammalian DNA replication forks encounter an unrepaired DNA lesion in the template strand, mammalian PCNA undergoes monoubiquitination, the covalent addition of a ubiquitin residue to PCNA [15] allowing the replacement of the high fidelity DNA polymerase delta with a low fidelity DNA polymerase that can insert DNA bases opposite the DNA lesion. Translesion DNA synthesis by a low fidelity DNA polymerase allows replication to proceed at the cost of mutagenesis. Pyrimidine dimers, a form of DNA damage caused by ultraviolet (UV) radiation, is an efficient inducer of monoubiquitinated PCNA in mammalian cells [16]. The importance of PCNA for genome stability, and the many known PCNA binding proteins, has given PCNA a reputation as the "ringmaster" or "maestro" of the genome [17, 18].

Simian virus 40 (SV40) is a DNA virus that makes extensive use of host cell DNA replication machinery and also packages its DNA in host cell-derived histones organized into nucleosomes [19]. This has led to the use of SV40 as a model for the mammalian replicon with many experimental advantages [20]. A major difference between SV40 and cellular DNA replication forks is the helicase. In SV40 replication forks, the virus-encoded large T antigen is the helicase, replacing the MCM helicase proteins of cellular replication forks [21]. The SV40 large t antigen is a circular hexamer composed of large t antigen monomers, and it is both a DNA and RNA helicase [22, 23]. Like the PCNA trimer, it encircles a DNA strand, and the binding between the subunits is non-covalent.

In this study, we show that structurally diverse anticancer drugs cause photodynamic damage, in the form of protein crosslinking, to proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and to SV40 large T antigen. The results provide new information on photodynamic protein-protein crosslinking in cells and show that enzymes of DNA replication and repair can be significantly photodamaged by common antineoplastic drugs, including those that localize in cytoplasmic organelles. Damage to such nuclear enzymes may compromise DNA damage signaling and repair, and thus alter cell survival and mutagenesis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

HeLa (human cervical cancer) and MCF-7 (human breast cancer) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Ca) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen). HeLa cells stably expressing HA-tagged PCNA (1), a gift from Dr. Niall Howlett (U. Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), were maintained in DMEM containing 1 µg/ml of puromycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 10% FBS. African green monkey kidney fibroblasts (CV-1) were obtained from the ATCC and cultured in MEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% calf serum (Invitrogen) and 14 mM HEPES (Sigma) (MEM/HEPES). CV-1 cells were infected with simian virus 40 (SV40, strain 777, 2.3 × 107 pfu/ml) for 1 hr at 37 °C and cultured with complete media for 36 hr before treatment with drugs [24]. SV40 transformed human fibroblast GM639 were obtained from the Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ) and were maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS. For experiments in deuterium oxide (D2O), powdered MEM was prepared in 99.9% D2O (Sigma) without serum. Cells in DMEM were maintained in water-jacketed incubators at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells in MEM/HEPES were maintained at 37°C in water-jacketed incubators with humidified room air. Experiments were done with cells in late log phase (80–90% confluent) to ensure a high level of replicating cells. The temperature sensitive ubiquitin conjugation mutant, ts85 [24] was maintained in DMEM with 10% FBS, at the permissive temperature, 32°C. For experiments to determine oxygen dependence, cells were grown in 25 cm2 tissue culture flasks. Nitrogen or air flushing was done through Luer stopcock controlled hypodermic needles inserted through silicone rubber stoppers used to seal the flasks. After flushing, the stopcocks were closed to seal the flasks.

2.2. Drugs and reagents

Proflavine, acridine orange, methylene blue, 9-aminoacridine, doxorubicin, hypericin, ethidium bromide, chloroquine, and ellipticine were from Sigma. Paraquat (methyl viologen dichloride hydrate), sanguinarine chloride, (S,R)-noscapine, 97%, and berberine hydrochloride hydrate, 99% were from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 tetrasodium salt (NPe6) was purchased from Frontier Scientific (Logan, UT). Camptothecin, m-amsacrine (m-AMSA, 4΄-(9-acridinylamino)methanesulfon-m-anisidide), and nitidine were obtained from the National Cancer Institute, Developmental Therapeutics Program (Frederick, MD). Proflavine, acridine orange, methylene blue, ethidium bromide, and NPe6 were prepared as stock solutions in distilled water. 9-aminoacridine, camptothecin, doxorubicin, ellipticine, and m-AMSA were dissolved in DMSO and hypericin was dissolved in methyl alcohol. Stock solutions were aliquoted and stored frozen in the dark at −20 °C. The E1 ubiquitin ligase inhibitor, PYR-41 was from BioGenova Corp. (Frederick, MD). Glutaraldehyde was purchased from Polysciences, Inc. (Warrington, PA). Other biochemicals from Sigma were sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), sodium deoxycholate, nonidet P-40 (NP-40), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), formaldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, dithiothreitol (DTT), desferoxamine, histidine, superoxide dismutase (SOD, EC 1.15.1.1), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), glycerol, mannitol, and ascorbic acid. The protease inhibitors, aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin were from USB (Cleveland, OH).

2.3. Irradiation

Two light sources were used in this study, a high intensity fluorescent light irradiator (irradiance of 75 W m−2), and room fluorescent lighting (recessed ceiling units: irradiance at the bench top: 1.3 W m−2). The irradiator consisted of an aluminum platform located below a bank of seven F8T5/D Sylvania Daylight™ fluorescent 8 watt 12” bulbs. Irradiance was measured with a Li-Cor LI-185B radiometer. The temperature of the samples, monitored with an electronic probe and maintained by a 12 watt cooling fan, was controlled at 25 ± 1.5 °C. Cells in 35 mm culture plates with 1 ml of serum-free medium (SFM) were irradiated with plate lids in place. Before and after irradiation, the samples containing photodynamic drugs were processed under darkroom conditions (dim red darkroom lights). Room fluorescent lighting was Luxline Terra-Lux F32T8/735 3500K. Radiant light exposures are expressed as J cm−2. All visible light irradiations were in the irradiator for 7 min giving a radiant dose of 3.15 J cm−2, unless otherwise indicated. No irradiations were longer than 10 minutes. UV exposure (as J m−2, 254 nm) was measured with a calibrated UVP J-225 meter (UVP, LLC, Upland, CA).

2.4. Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Cells were treated with drugs for 30 min, the medium was replaced with SFM, and the cells were irradiated as indicated. Controls were cells receiving the same light exposure but without drugs present. Whole cell protein extracts were prepared in SDS lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 10 µg/ml of each protease inhibitor, aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. Proteins (20–40 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT) using a BioRad (Hercules, CA) semi-dry transfer system. Blocked membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, rinsed, then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hr at room temperature. Protein was detected by SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescence Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using either X-ray film or the BioRad ChemiDoc™ XRS imaging system. Primary antibodies were mouse PC10 or goat C20 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA) directed against PCNA, mouse anti-HA tag (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), mouse anti-SV40 large T antigen (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA), goat anti-lamin B (Santa Cruz), goat anti-triose phosphate isomerase (Novus, Littleton, CO), and mouse monoclonal anti-ubiquitin (Biomol, Exeter, UK). Secondary antibodies were goat antimouse HRP conjugate (BioRad) and donkey anti-goat HRP conjugate (Santa Cruz). The apparent molecular weight of each PCNA form induced by photodynamic damage was estimated by comparison to commercial marker sets: Precision Plus Protein™ Dual color standards (BioRad) and EZ-Run™ pre-stained Rec Protein ladder (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

For immunoprecipitation, HeLa cells were treated with 40 µM proflavine or 60 µM acridine orange for 30 min, changed to drug-free, SFM, and then irradiated with fluorescent light (3.15 J cm−2). Cells were lysed using SDS lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. For PCNA immunoprecipitation, proteins were precleared with Pansorbin® cells and immunopure rabbit serum (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), then incubated with PC10 antibody (4 µg/tube) at 4 °C overnight on a rotator. Antibody-bound protein lysates were incubated with Protein A agarose beads (Calbiochem) with rotation for 4 hrs at 4 °C. Protein-antibody-bead complexes were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (BioRad). For the HA-tagged PCNA protein pull-down, proteins from proflavine and light treated HeLa cells expressing HA-tagged PCNA were extracted using RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH8.0, aprotinin 1 µg/ml, leupeptin 1 µg/ml, pepstatin 1 µg/ml, and PMSF 50 µg/ml) and processed using a ProFound™ HA-Tag IP/Co-IP set (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Proteins eluted from immobilized antibody-bead complexes were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting with PC10 or HA tag antibodies was carried out. For proteomic identification of PCNA crosslinked proteins, the acrylamide gel was Coomassie Blue stained and the protein band of interest was excised for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) analysis.

2.5. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

Two-dimensional electrophoresis was performed at Kendrick Laboratories, Inc. (Madison, WI) according to O’Farrell [25]. Isoelectric focusing was carried out using 2% pH 3.5–10 ampholines (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) for 9600 V-hrs. 10% SDS-PAGE slab gel electrophoresis was carried out for 4 hr at 15 mA/gel. The following proteins (Sigma) were used as molecular weight markers: myosin (220,000), phosphorylase A (94,000), catalase (60,000), actin (43,000), carbonic anhydrase (29,000) and lysozyme (14,000). The pH gradient was determined using a surface pH electrode on four blank IEF tube gels.

2.6. Mass spectrometry

Excised Coomassie stained protein bands from SDS-PAGE were analyzed at the Ohio State University Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility. LC/MS/MS was performed on a Thermo Finnigan LTQ mass spectrometer equipped with a nanospray source operated in positive ion mode. The scan sequence of the mass spectrometer was programmed for a full scan and MS/MS scans of the 10 most abundant peaks in the spectrum. Dynamic exclusion was used to exclude multiple MS/MS of the same peptide after detecting it three times. Sequence information from the MS/MS data was processed using the Mascot 2.0 active Perl script. Database searches were against the NCBInr database using MASCOT 2.0 (Matrix Science, Boston, MA). The mass accuracy of the precursor ions was set to 1.8 Da, and the fragment mass accuracy was set to 0.5 Da. The number of missed cleavages permitted in the search was 2. An individual peptide was considered as a good match if it produced a probability-based MOWSE (MOlecular Weight SEarch [26]) score greater than 20 (P<0.05). The cut-off score for significant protein identification was set at 45 and the matched peptides were all manually verified.

3. Results

3.1. High molecular weight PCNA forms produced by photodynamic damage

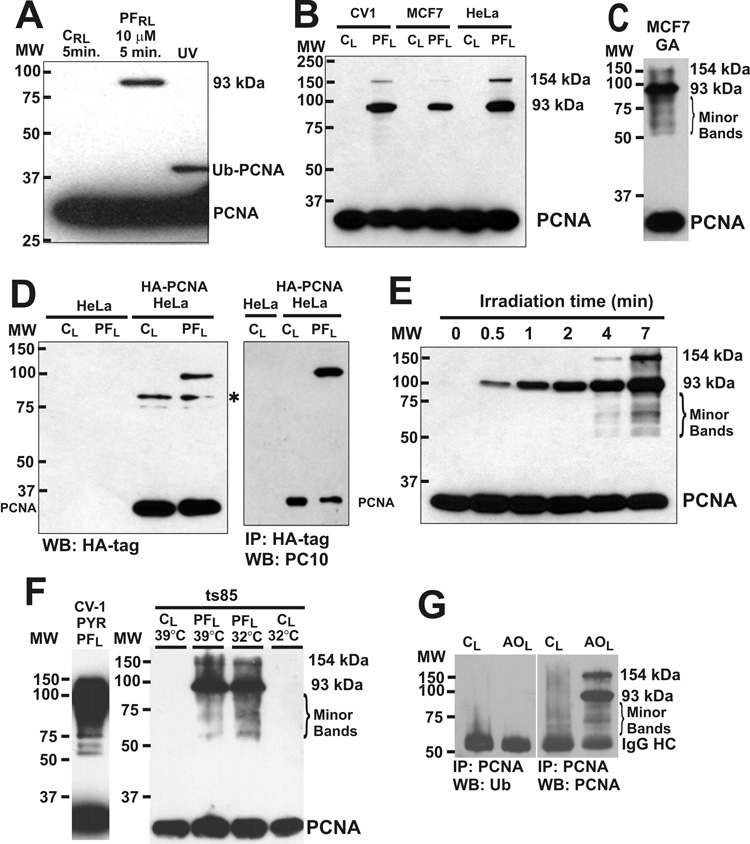

Western blotting of whole cell lysate from CV-1 cells treated with 10 µM proflavine during a brief exposure to room fluorescent lighting revealed a high molecular weight PCNA-antibody reactive protein band of about 93 kDa (Fig. 1A). As controls, CV-1 cells were irradiated without proflavine (Fig. 1A CRL), or were UV irradiated (Fig. 1A, UV) to induce mono-ubiquitinated PCNA [27, 28]. More intense visible light irradiation of proflavine-treated cells produced the 93 kDa PCNA reactive band, and a higher molecular weight (~154 kDa) band in CV-1, MCF-7 and HeLa cells (Fig. 1B). A RIPA lysate of MCF-7 cells was treated with glutaraldehyde, a protein crosslinking agent, subjected to SDS PAGE (12% acrylamide), then Western blotted using anti-PCNA antibody. Glutaraldehyde is known to covalently crosslink PCNA trimers to produce a high molecular weight PCNA band at about 93 kDa on SDS PAGE [12]. The major high molecular weight PCNA band produced by glutaraldehyde crosslinking corresponds to the major high molecular weight band produced by proflavine and light, suggesting that the 93 kDa PCNA band produced by proflavine and light represents the covalently crosslinked PCNA trimer. In addition, a higher molecular weight PCNA form of about 154 kDa was produced. A number of minor high molecular weight PCNA bands were also detected in the region below the 93 kDa band (Fig. 1C, Minor Bands). An experiment was done using cells expressing HA-PCNA to determine if the high molecular weight PCNA band was due to nonspecific binding of the anti-PCNA PC10 antibody to photodynamically damaged proteins. The 93 kDa band was detected with HA tag antibody in HeLa cells expressing HA-tagged PCNA and was also detected with the PC10 antibody after HA-tag immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1D). Development of these high molecular weight PCNA bands as a function of irradiation time was studied with CV-1 cells, and a number of weaker high molecular weight PCNA antibody-reactive bands, similar to those in the glutaraldehyde experiment, were evident at longer irradiation times (Fig. 1E, Minor Bands). Detection of the minor high molecular weight PCNA bands was dependent on irradiation time, drug concentration and chemiluminescent film exposure time.

Fig. 1.

High molecular weight PCNA forms produced by proflavine and light. A. CV-1 cells in SFM were exposed to room lighting for 5 min on the bench top (0.039 J cm−2) without (CRL), or with (PFRL) 10 µM proflavine treatment (37°C, 30 min). Other cells were UV-irradiated (UV, 30 J m−2), incubated 3hr in serum-containing MEM, and Western blotted with PCNA antibody (PC-10). MW, Molecular weight; PCNA, PCNA monomer; Ub-PCNA, monoubiquitinated PCNA; 93 kDA, 93 kilodalton PCNA form. B, CV-1, MCF-7, and HeLa cells in SFM were exposed to light in the irradiator (7 min, 75 W m−2, 3.15 J cm−2) without (CL) or with 40 µM proflavine (PFL). C, A RIPA lysate of MCF-7 cells was treated with glutaraldehyde (GA, 0.025%, 10 min, 37°C), glycine was added to 0.15 M to stop protein crosslinking, and the sample was Western blotted (anti-PCNA). Minor high molecular weight PCNA bands are indicated (Minor Bands) with 93 kDa and 154 kDa bands. D, HeLa cells and HeLa cells expressing HA-tagged PCNA (HA-PCNA HeLa) in SFM were exposed to light (3.15 J cm−2) without (CL) or with 40 µM proflavine (PFL), then Western blotted with HA tag antibody. Asterisk: non-specific band. HeLa cells expressing HA tagged PCNA were also immunoprecipitated with HA-tag antibody, then Western blotted with PCNA antibody. E, CV-1 cells treated with 40 µM proflavine in SFM were irradiated for different times (75 W m−2), and anti-PCNA Western blotting was performed. The zero time point is a dark control. F, CV-1 cells treated with the E1 ubiquitin ligase inhibitor, PYR-41 (25 µM), proflavine (40 µM) and light (3.15 J cm−2), were analyzed by PCNA Western blotting. ts85 cells, capable of ubiquitination at 32°C but not at 39°C, were incubated at each temperature for 16 hr, then treated with 40 µM proflavine and light (3.15 J cm−2) and analysed by PCNA Western blotting. G, CV-1 cells were treated with 40 µM acridine orange and light (3.15 J cm−2). SDS lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-PCNA antibody, and Western blotted with anti-ubiquitin antibody (left) before re-probing with anti-PCNA antibody (right).

Experiments were done to determine if the high molecular weight PCNA bands were due to polyubiquitination of PCNA. The pattern of high molecular weight PCNA bands caused by proflavine and light was not affected by treatment of the cells with the E1 ubiquitin ligase inhibitor, PYR-41, or by shifting the murine temperature-sensitive ubiquitin conjugation mutant, ts85, to the restrictive temperature (Fig. 1F). The 93 kDa band, the 154 kDa band and the minor high molecular weight bands did not react with ubiquitin antibody after PCNA immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1G).

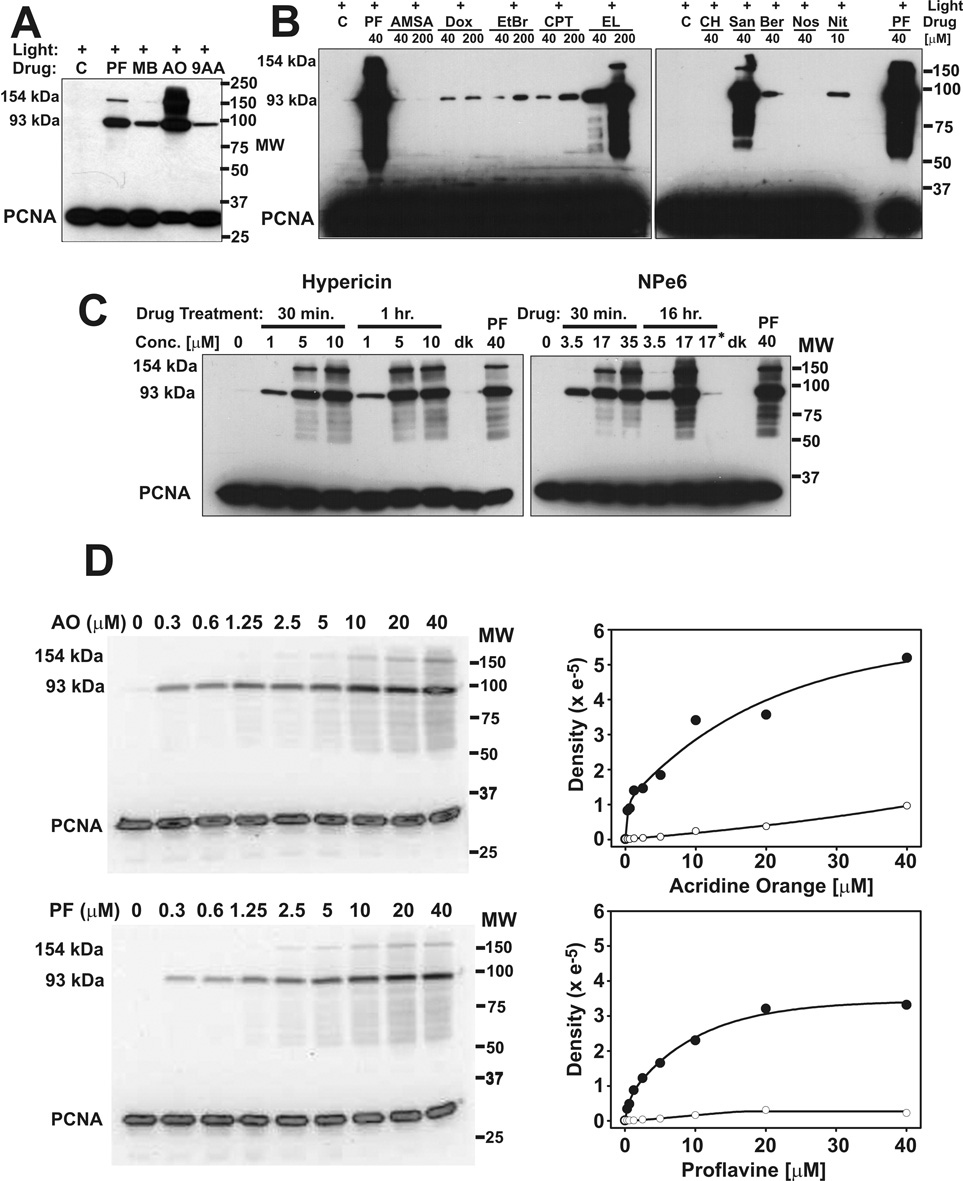

Since many drugs and natural products are at least weakly photodynamic [29–31] we extended the study to other commonly used drugs and reagents. The DNA intercalating photodynamic dyes, methylene blue, acridine orange, and 9-aminoacridine produced strong 93 kDa bands in CV-1 cells when irradiated with visible light (Fig. 2A). At the same drug concentration and radiant exposure, proflavine and acridine orange produced similar levels of the 93 kDa PCNA form, but very different levels of the 154 kDa form. Topoisomerase poisons and other drugs were also studied for their ability to photodamage PCNA, with ethidium bromide and proflavine as positive controls and noscapine as a negative control (Fig. 2B). Ellipticine and sanguinarine produced very strong 93 kDa and 154 kDa bands as well as the minor high molecular weight PCNA bands. Camptothecin, doxorubicin, berberine, nitidine, and ethidium bromide produced weak 93 kDa bands when irradiated with fluorescent light. None of these drugs caused high molecular weight PCNA forms when incubated with the cells in the dark (Supplemental Fig. S1). m-AMSA, chloroquine and noscapine did not produce detectable high molecular weight PCNA bands with exposure to light. The experiment was repeated, using a BioRad ChemiDoc™ XRS imaging system to quantitate the area of each lane corresponding to the 93 kDa band (not shown), and confirmed that m-AMSA and light exposure did not produce a detectable high molecular weight PCNA band.

Fig. 2.

PCNA photo-crosslinking by diverse drugs (radiant light exposures 3.15 J cm−2). A, CV-1 cells were treated with 40 µM proflavine (PF), methylene blue (MB), acridine orange (AO), 9-aminoacridine (9AA) in serum-free medium, or with serum-free medium alone (C) for 30 min before irradiation. B, Proflavine (PF), m-AMSA (AMSA), doxorubicin (Dox), ethidium bromide (EtBr), camptothecin (CPT), ellipticine (EL), chloroquine (CH), sanguinarine (San), berberine (Ber), noscapine (Nos), and nitidine (Nit) were added to cells for 30 min before irradiation. C, Cells were exposed to different concentrations of hypericin or NPe6 for the indicated times before irradiation. Controls included untreated cells (0 µM) receiving the same light exposure, cells treated with 40 µM proflavine and light, cells treated with either 10 µM hypericin or 17 µM NPe6 for 1 hr but kept in the dark (dk), and cells treated with NPe6 for 1 hr in serum containing medium before irradiation (indicated with an asterisk). D, Cells were treated with proflavine or acridine orange at the indicated concentrations and then irradiated. Anti-PCNA Western blots (AO and light, upper left; PF and light, lower left) were visualized and quantitated with the BioRad ChemiDoc™ XRS imaging system. Quantitation of the 93 kDa PCNA (●) and the 154 kDa PCNA (○) bands is shown to the right of each Western blot.

Hypericin, an endoplasmic reticulum localizing drug [32], was a very effective photodynamic producer of the 93 and 154 kDa bands, as well as the minor high molecular weight PCNA bands produced by proflavine (Fig. 2C). NPe6, a lysosome localizing drug [33] was also effective, although its effectiveness was greatly reduced by serum in the medium (Fig. 2C). To test the possibility that these drugs might reach PCNA as a result of nuclear membrane breakdown during mitosis, the experiment was also done in SV40 infected CV-1 cells that are locked into DNA synthesis and unable to progress to mitosis [34–36]. The infection was done at high multiplicity of infection (M.O.I. = 20 plaque-forming units per cell) to ensure that all cells were infected. Both drugs efficiently caused the formation of the high molecular weight PCNA forms in SV40 infected CV-1 cells when exposed to light (Supplemental Fig. S2).

3.2. Dose-response for high molecular weight PCNA forms

The Western blots in Figure 1E and Figure 2A suggest that the rate of formation of the 93 kDa PCNA band may differ from the rate of formation of the minor high molecular weight PCNA bands (including the 154 kDa band), and also suggest that the ratio of the major to minor bands may be different for different drugs (compare proflavine and acridine orange in Fig. 2A). To examine this more closely, the dose-responses for acridine orange and proflavine were compared quantitatively. The density of the 93 kDa band increased steeply as a function of drug concentration for both proflavine and acridine orange (Fig. 2D), but reached a plateau in the proflavine sample while continuing to increase at comparable concentrations of acridine orange. In both the acridine and proflavine experiments, the 154 kDa band showed a very different dose-response than the 93 kDa band. Minor high molecular weight PCNA bands, most located below the 93 kDa band, had a dose-response similar to the 154 kDa band.

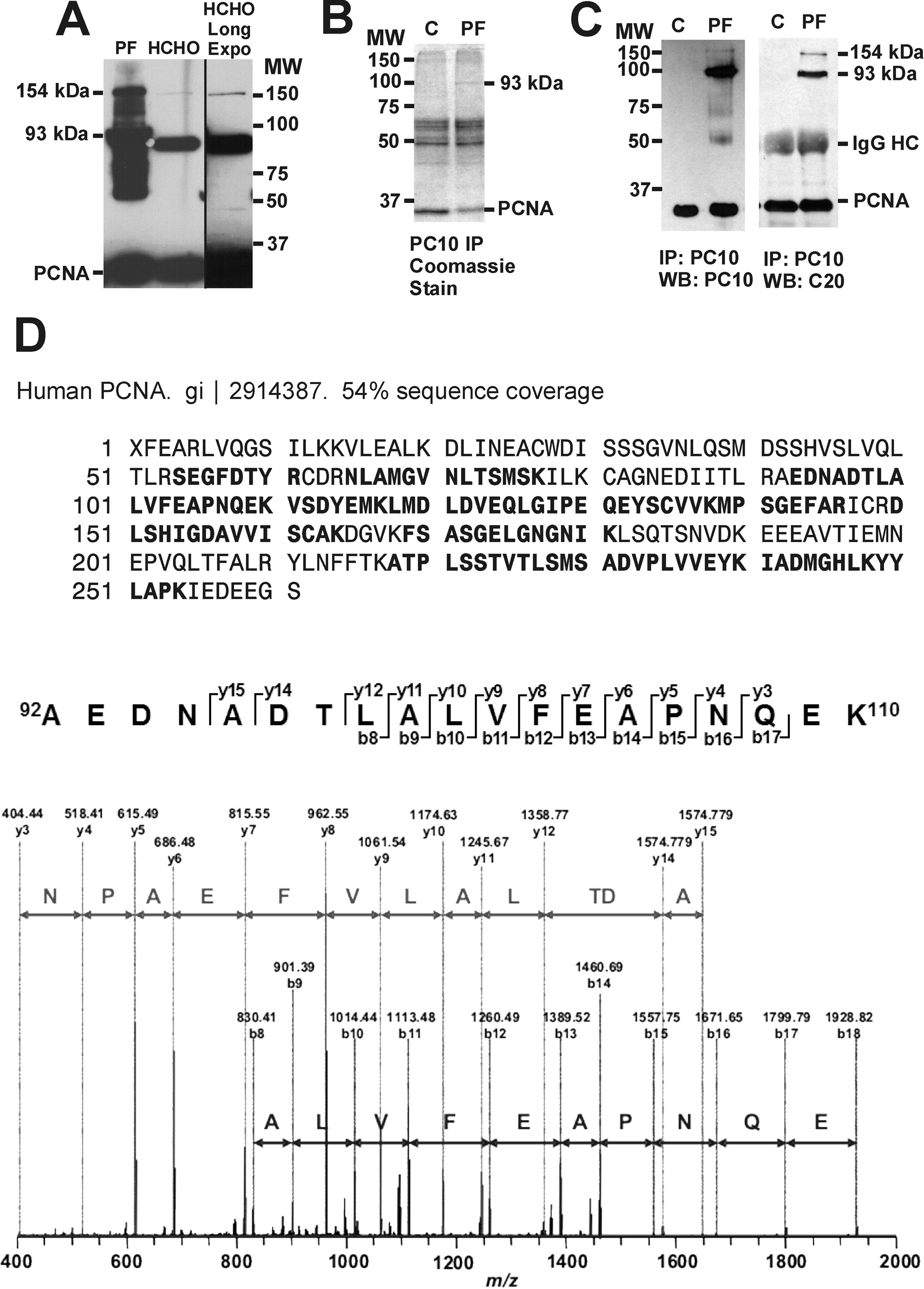

3.3. Identification of the 93 kDa band as a PCNA trimer

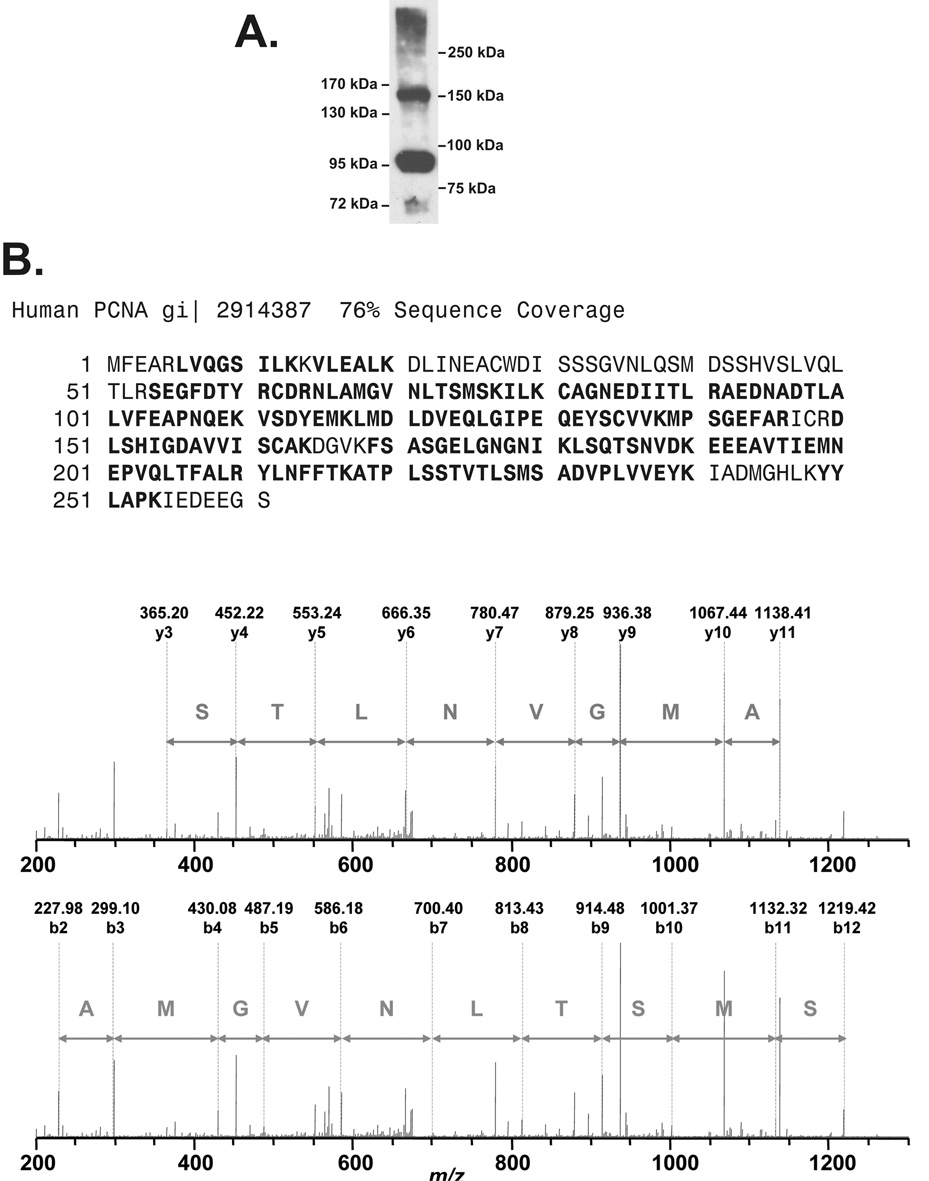

Formaldehyde treatment of cells covalently crosslinks PCNA trimers [13, 37]. Comparison of the high molecular weight PCNA forms produced by proflavine plus light and formaldehyde crosslinking showed somewhat different electrophoretic mobilities for the major high molecular weight PCNA bands, and numerous additional bands in the proflavine sample that were not detected by formaldehyde crosslinking (Fig 3A). To determine if the 93 kDa band represented the PCNA trimer or PCNA crosslinked to a heterologous protein, a proteomic experiment was undertaken. Immunoprecipitation of PCNA followed by gel electrophoresis was shown to produce a Coomassie staining band at the position of the 93 kDa band seen in Western blots (Fig. 3B). PCNA immunoprecipitates, Western blotted with PC10 monoclonal and C20 polyclonal antibodies to PCNA, confirmed that the Coomassie band at 93 kDa contained PCNA (Fig. 3C). LC/MS/MS analysis identified this band as PCNA with 54% sequence coverage, a Mowse score of 621, and several high confidence peptide sequences such as that of the peptide AEDNADTLALVFEAPNQEK (Fig. 3D). No peptides of other proteins were detected.

Fig. 3.

The 93 kDa band is the crosslinked PCNA trimer. A, HeLa cells were treated with 40 µM proflavine (PF) and light (3.15 J cm−2) or with 1.5 % formaldehyde (HCHO) for 30 min at room temperature. The proflavine plus light treated cells were lysed with SDS lysis buffer, and the formaldehyde treated cells were lysed with RIPA buffer following the protocol of Naryzhny et al. [13, 37]. The proteins from the two samples were Western blotted with PC10 antibody. A longer film exposure of the HCHO lane shows the 154 kDa PCNA positive band. B, PCNA from cells exposed to 40 µM proflavine and light (PF, 3.15 J cm−2) and control cells exposed to light alone (C) was immunoprecipitated from a HeLa cell RIPA lysate with PC10 antibody. Proteins of the immunoprecipitate were visualized by Coomassie staining. C, PC10 immunoprecipitated HeLa samples were Western blotted with PC10 and C20 antibodies. The IgG heavy chain from the immunoprecipitation is indicated (IgG HC). D, The 93 kDa Coomassie stained band was excised, trypsin digested, and processed for LC/MS/MS. PCNA amino acid sequences detected by LC/MS/MS are indicated in bold. Sequence tags for the unique PCNA tryptic peptide AEDNADTLALVFEAPNQEK are shown.

3.4. Identification of the 154 kDa band as a PCNA oligomer

Acridine orange was used in a proteomic study to identify the protein or proteins in the 154 kDa band, since it is the most efficient producer of this band under the conditions of our irradiator (Fig. 2A). High molecular weight PCNA bands produced by acridine orange and light were compared to two high molecular weight marker protein ladders (Fig. 4A). Two prominent, well resolved PCNA antibody-reactive bands migrated at positions corresponding to molecular weights of 93 kDa and 154 kDa respectively. A lysate of HeLa cells exposed to 60 µM acridine orange and light was concentrated using a 50 kDa cutoff centrifugal filter to reduce the amount of PCNA monomer for the subsequent immunoprecipitation. After PCNA immunoprecipitation and SDS PAGE, the Coomassie-stained PCNA band at 154 kDa was analyzed by LC/MS/MS. PCNA was identified with a sequence coverage of 76%, high quality peptide sequences, such as NLAMGVNLTSMSK (Fig. 4B), and a protein score of 907. A small, diverse set of proteins with low protein scores and few matched peptides, usually single peptides, was also detected (Table 1). Three candidate heterologous PCNA interacting proteins were tested by Western blotting. The 154 kDa band was not detected with antibodies to beta actin (Sigma), nucleolin (Santa Cruz) or Caf1 p60 (Santa Cruz).

Fig. 4.

The 154 kDa Band is a PCNA oligomer. A, Western blot of PCNA forms produced by 40 µM acridine orange and light (3.15 J cm−2) in HeLa cells. SDS PAGE (7% acrylamide) was done with the PCNA monomer run off the gel for maximum resolution in the high molecular weight range. Two molecular weight marker sets were used: EZ-Run™ pre-stained Rec Protein Ladder (left side markers) and Precision Plus Protein™ Dual color standards (right side markers). B, LC/MS/MS results. PCNA sequence coverage (bold) for the 154 kDa band determined by nano-LC/MS/MS of the Coomassie stained band after tryptic digestion, with sequence tags for the PCNA peptide NLAMGVNLTSMSK.

Table 1.

154 kDa PCNA-positive species candidate proteins. Candidate proteins components of the 154 kDa form are indicated, with protein scores that reflect the probability of correct identification.

| Protein | Molecular weight | Sequence coverage | Queries Matched | Protein Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCNA | 29.1 kDa | 76% | 54 | 907 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L6 | 32 kDa | 11% | 3 | 158 |

| nucleolin | 76.6 kDa | 13% | 7 | 146 |

| cytoplasmic beta actin | 42 kDa | 9% | 4 | 127 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L7 | 29.2 kDa | 10% | 3 | 116 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L4 | 47.9 kDa | 14% | 5 | 116 |

| Histone H1.2 | 21.3 kDa | 14% | 4 | 112 |

| Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, mitochondrial precursor | 166 kDa | 7% | 8 | 108 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U | 91 kDa | 3% | 3 | 104 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase | 165 kD | 5% | 7 | 102 |

Protein score is -10*Log(P), where P is the probability that the observed match is a random event. Protein scores greater than 67 are significant (p<0.05).

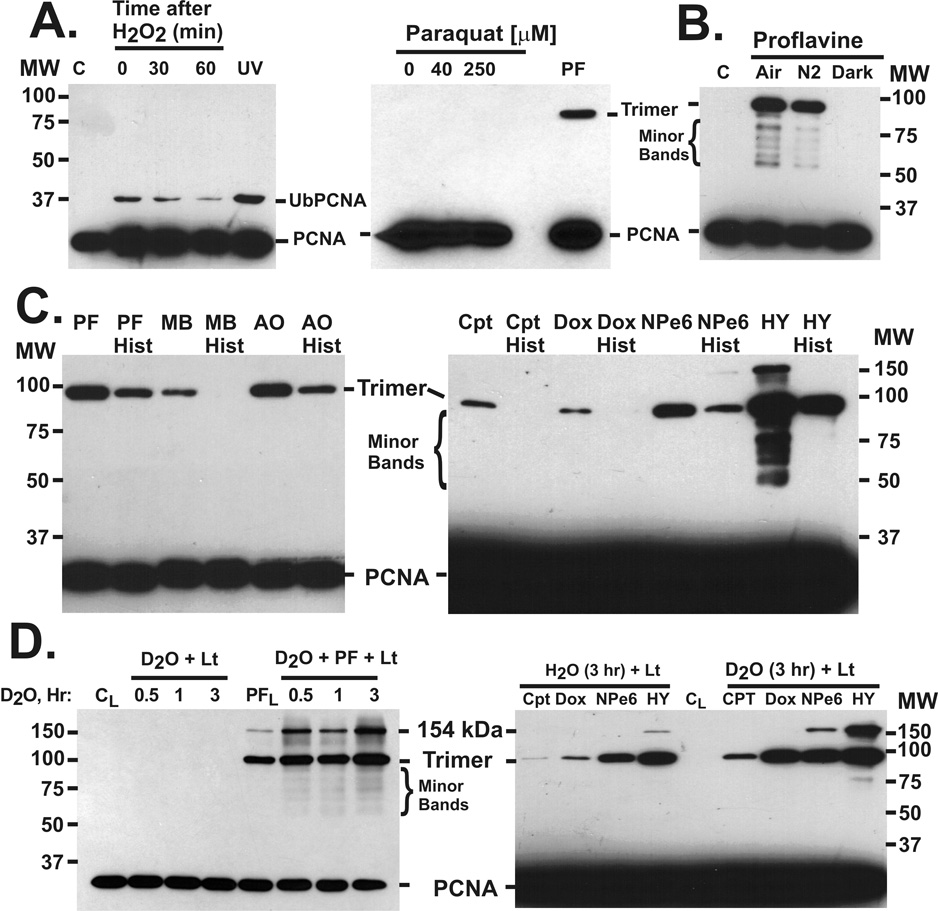

3.5. Tests for ROS involved in photodynamic crosslinking of PCNA

Since photodynamic drugs can generate a number of ROS in light, we carried out tests to identify the ROS responsible for covalent crosslinking of PCNA trimers. Hydrogen peroxide treatment did not cause the high molecular weight PCNA forms, but did cause transient monoubiquitination of PCNA (Fig. 5A). Treatment of cells with paraquat, a superoxide generating compound [38], did not produce high molecular weight PCNA forms (Fig.5A). To test for oxygen dependence, cell cultures were flushed with nitrogen, which reduced photodynamic crosslinking of PCNA by ~40–50% (Fig. 5B). Pre-treatment of cells with histidine, an efficient quencher of singlet oxygen [39] that is often used to test for the role of singlet oxygen in biological responses [40], significantly reduced the light-dependent production of high molecular weight PCNA bands by proflavine, methylene blue, acridine orange, camptothecin, doxorubicin, NPe6, and hypericin (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Tests for ROS causing PCNA crosslinking. CV-1 cells were lysed in SDS lysis buffer after the treatments, and the lysates were subjected to SDS gel electrophoresis (10% acrylamide). Western blotting was done with PC10 antibody against PCNA. A, Hydrogen peroxide exposure. Cells were treated with 5 mM H2O2 in SFM for 30 min, then the H2O2 medium was replaced with MEM supplemented with 10% calf serum for the times indicated. Untreated cells were a control (C). For the UV control, cells were exposed to germicidal UV light (30 J m−2), then extracted 3 hr later. Cells were treated with 40 or 250 µM paraquat (30 min, 37°C), or 40 µM proflavine and light (0.2 J cm−2) as a control. B, Oxygen dependence. Cells were changed to SFM, with or without 40 µM proflavine, flushed with room air (Air) or with nitrogen (N2) for 1 hr, then irradiated (1.35 J cm−2). Controls include cells not treated with proflavine (C), and cells treated with proflavine and flushed with air, but kept in the dark (Dark). C, Histidine suppression. Left: Cells were pretreated with SFM or with SFM containing 50 mM L-histidine (Hist) for 1.5 hr, and with 40 µM proflavine, methylene blue or acridine orange for the last 30 min. After incubation in the dyes, the cells were irradiated (0.9 J cm−2). Right: Cells were pretreated with SFM or with 100 mM histidine in SFM for 1.5 hr and then with camptothecin (200 µM), doxorubicin (200 µM), NPe6 (1.7 µM), or hypericin (0.5 µM) before irradiation (3.15 J cm−2). D, D2O enhancement. Left: Cells were treated for the times indicated with SFM made up in 99.9% D2O or in normal SFM, then the cells were irradiated (3.15 J cm−2) either in D2O alone or in D2O containing 40 µM PF. Light irradiated control (CL) and proflavine (PFL, 40 µM) experiments were in media made up with deionized water. Right: Cells were treated with D2O media for 3 hr, then with camptothecin (200 µM), doxorubicin (200 µM), NPe6 (1.7 µM), or hypericin (0.5 µM) before irradiation (3.15 J cm−2). Controls were identically treated but with SFM made in deionized water. Irradiated control cells (CL) are indicated.

D2O enhances the biological effects of singlet oxygen [41] by increasing the lifetime of singlet oxygen by up to 20-fold [42]. Irradiation of proflavine treated cells in D2O medium increased the photodynamic production of high molecular weight PCNA forms, and this effect of D2O was more pronounced with longer D2O exposure times (Fig. 5D). No covalent crosslinking of PCNA trimers was detected in the absence of drugs, even in D2O. Light dependent covalent crosslinking of PCNA trimers by camptothecin, doxorubicin, NPe6, and hypericin was also enhanced by D2O (Fig. 5D). The D2O enhancement was quantitated (data not shown) and found to be ~2.4-fold for camptothecin and NPe6, 10-fold for doxorubicin, and 2-fold for hypericin. These relative enhancements were very reproducible. Hydroxyl radical quenchers (mannitol, DMSO, ethanol, ascorbate), superoxide dismutase, DTT, and desferoxamine had no significant effect on PCNA photo-crosslinking by proflavine and light (Supplemental Fig. S3A and B).

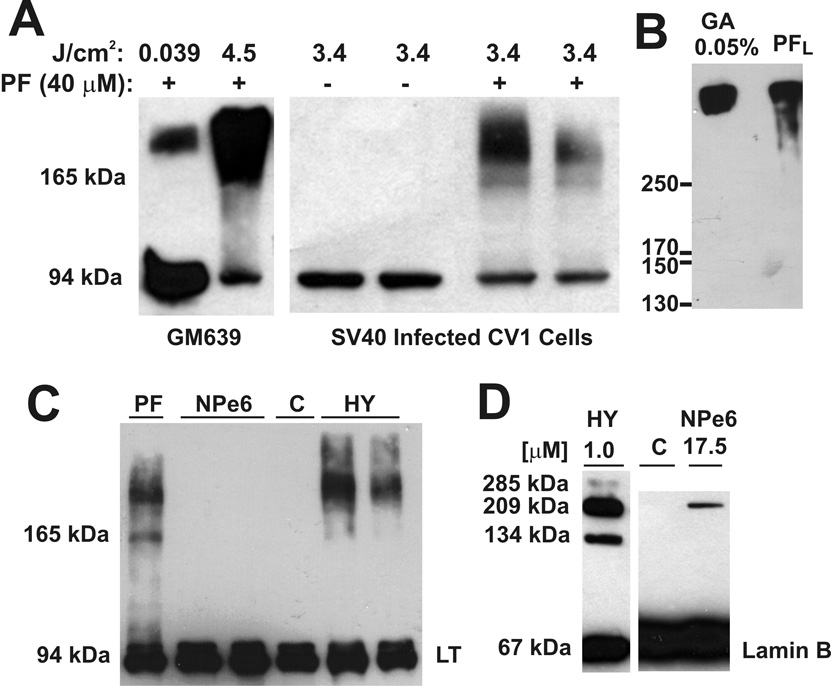

3.6. Photodynamic crosslinking of SV40 large T antigen and lamin B

Brief exposure (5-min) of proflavine-treated SV40 transformed human cells to laboratory room lighting (0.039 J cm−2) produced a high molecular weight large T antigen band as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 6A, left). More extensive exposure in the irradiator (4.5 J cm−2) resulted in an increase in the high molecular weight large T antigen band and a corresponding decrease in the monomer. Irradiation of proflavine treated SV40 infected CV-1 cells to an intermediate radiant exposure (3.4 J cm−2) revealed a weaker band at the expected position of the large T antigen dimer (Fig. 6A, right). Glutaraldehyde covalently crosslinks large T antigen hexamers, causing them to migrate at a position corresponding to ~500 kDa by gel electrophoresis [43]. Glutaraldehyde crosslinking resulted in a high molecular weight large T antigen band corresponding to that produced by proflavine and light (Fig. 6B). The pattern of large T antigen crosslinking by proflavine plus light was the same for both SV40-transformed human fibroblasts (GM639) and SV40 infected CV-1 cells. Hypericin also caused substantial covalent crosslinking of large T antigen, but NPe6 did not (Fig. 6C). There was strong lamin B photo-crosslinking with hypericin, as reported by others [44], and weak lamin B crosslinking with NPe6 (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Photodynamic crosslinking of SV40 large T antigen and lamin B. A, SV40-transformed human fibroblasts (GM639) were briefly exposed to laboratory room lighting (1.3 W m−2) at bench top level for 5 min (0.039 J cm−2) and also exposed to more intense light (75 W m−2) in the irradiator (10 min, 4.5 J cm−2). SV40-infected CV-1 cells, with or without proflavine (40 µM, 30 min, 37 °C), were also exposed to light in the irradiator as indicated. SDS PAGE and Western blotting with anti-SV40 large T antigen (LT) were performed. B, Glutaraldehyde (GA) crosslinking of large T antigen in a RIPA extract, compared to large T antigen crosslinked by proflavine (40 µM) plus light (PFL, 0.234 J cm−2) in GM639 cells. Large T antigen monomer was run off the 6% acrylamide SDS gel to achieve higher resolution of the high molecular weight crosslinked forms before Western blotting with anti-large T antigen antibody. C, GM639 cells were treated with 5 µM proflavine, 5 µM NPe6, and 5 µM hypericin for 1 hr at 37 °C, and then were irradiated (3.15 J cm−2). Anti-SV40 large T antigen Western blotting was done. Controls (C) were GM639 cells without drug or light exposure. D, GM639 cells were treated with hypericin (1 hr) or NPe6 (30 min) at 37°C and the indicated concentrations before irradiation (3.4 J cm−2). Western blotting with anti-lamin B antibody. Controls (C) were GM639 cells without drug or light exposure.

3.7 Photodynamic changes in cellular proteins

Whole cell proteins from MCF-7 cells exposed to 40 µM proflavine and light (0.9 J cm−2) were compared to proteins from untreated cells by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Fig. S4). Of the ~300 protein spots, only 7 (2%) were changed by the treatment (2 increased, 5 decreased). Triose phosphate isomerase, a representative cytoplasmic protein, was unaffected by high levels of photodynamic damage (40 µM proflavine, 3.15 J cm−2) as determined by Western blotting (not shown). As observed by others [45, 46], we found that actin was not oligomerized, crosslinked to other proteins, degraded or lost to detection by antibodies, even with high levels of photodynamic damage.

4. Discussion

High molecular weight forms of PCNA, stable to SDS denaturation, were detected in lysates of cells exposed to fluorescent light after treatment with a structurally and functionally diverse set of drugs. The high molecular weight PCNA forms were not due to ubiquitination of PCNA since they were not caused by UV, which induces monoubiquitination of PCNA in mammalian cells [27, 28], were not detected by anti-ubiquitin antibody, and were not prevented by inhibition of ubiquitin conjugation. The 93 kDa form was identified as the covalently crosslinked PCNA trimer based on anti-HA-PCNA reactivity, molecular weight and identification as only PCNA by LC/MS/MS with high sequence coverage and without detection of peptides of other proteins. The 154 kDa PCNA band was identified as a PCNA oligomer based on anti-PCNA reactivity, and good LC/MS/MS sequence coverage and protein score. Peptides of other proteins were detected, but with very low sequence coverage and confidence scores, suggesting that they represent trace contaminating proteins. Their molecular weights also could not explain the shift of PCNA or the PCNA trimer to the 154 kDa position. Western blotting for PCNA interacting proteins CAF1, nucleolin, and β-actin did not detect the 154 kDa species. The 154 kDa form is similar in size to a PCNA oligomer formed from formaldehyde crosslinking that has been suggested to be a covalently crosslinked PCNA double trimer [13]. Minor high molecular weight PCNA forms, most migrating ahead of the 93 kDa band, were identified as heterologous proteins crosslinked to PCNA based on their molecular weights and formation by glutaraldehyde treatment of a cell lysate. However, one of these minor high molecular weight PCNA forms may be a PCNA dimer [12].

The kinetics and dose-response for formation of the PCNA trimer appear to differ from those of the 154 kDa band and the minor high molecular weight PCNA bands (Fig. 1E and Fig. 2D). As the core of a molecular machine, the PCNA trimer is held together by tight inter-subunit binding which probably facilitates the efficient covalent crosslinking of the trimer. In contrast, PCNA interactions with heterologous proteins are weak and transient [17], which would make them less subject to covalent crosslinking. The dose-response and kinetic data are consistent with the idea that the minor high molecular weight bands are due to crosslinking of heterologous proteins to PCNA monomers or the PCNA trimer. The 154 kDa species falls into this class based on kinetics and dose-response, yet is composed only of PCNA. This suggests that it is formed by crosslinking of additional PCNA to the crosslinked PCNA trimer. The interaction of this additional PCNA with the PCNA trimer would presumably involve relatively weak, transient binding, similar to the interactions between heterologous proteins and the trimer. The additional PCNA photocrosslinked to the trimer may be PCNA monomers or a second PCNA trimer, as suggested by formaldehyde crosslinking studies [13].

Like PCNA, SV40 large T antigen functions as a circular oligomer. The PCNA trimer and the large T antigen hexamer are both exquisitely sensitive to photodynamic crosslinking, since micromolar concentrations of proflavine caused crosslinking in five minute exposures to room fluorescent lighting. Other studies have shown that STAT3 photodynamic crosslinking is a good marker of photodynamic damage and cytotoxicity [47]. Since PCNA is distributed throughout the nucleus [48] and more than 95% of large T antigen in SV40 transformed cells is nuclear [49], PCNA and large T antigen appear to be very sensitive markers of photodynamic damage in the nucleus.

The extent of PCNA photo-crosslinking varies greatly for cells treated with different drugs at the same concentration and given the same radiant exposure of fluorescent light (Fig. 2, A & B). The pattern of PCNA crosslinking by different drugs is similar, and resembles that of PCNA crosslinking by glutaraldehyde. Although the high molecular weight PCNA bands are the same, their relative intensities differ for different drugs (compare AO and PF in Fig. 2A). Photodynamic damage to a target from any one drug may be a complex function of absorption spectrum, and ratio of type I to type II mechanisms, subcellular localization, and binding of the drug to intracellular molecules and structures [50, 51].

Only a few proteins from cells treated with proflavine and light showed altered mobility on 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis. This is consistent with a two-dimensional gel analysis of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodamage that found 7 protein spots increased and 17 decreased out of ~1350 spots resolved (1.8 % of proteins affected) [52]. It is apparent that extensive protein crosslinking or degradation is not occurring under our conditions. None of the changed proteins have the molecular weight, isoelectric point or abundance expected for PCNA. There was no detectable breakage of peptide backbones or loss of epitope reactivity in the proteins we studied by Western blotting (PCNA, the HA tag, SV40 large T antigen, triose phosphate isomerase, lamin B, and actin). Excellent sequence coverage in the LC/MS/MS studies is also consistent with very low levels of peptide backbone cleavage and amino acid residue damage. Our results indicate that photodynamic protein crosslinking in cells strongly favors self-crosslinking of a limited set of proteins that exist as oligomers, with crosslinking between heterologous proteins being less efficient by orders of magnitude. As shown by actin, not all oligomerizing proteins are crosslinked by photodynamic damage [53, 54].

The photodynamic drugs in this study known to generate singlet oxygen (type II mechanism) include proflavine [Reviewed in: 55], acridine orange [Reviewed in: 56], methylene blue [57], 9 aminoacridine [51], ethidium bromide [58], camptothecin [59], doxorubicin [60], berberine [50, 61], sanguinarine [62], hypericin [63], and NPe6 [64]. Most of these drugs also produce other ROS in light (type I mechanism). Nitidine is structurally related to sanguinarine and berberine, but we could find no reports of photodynamic activity for nitidine itself. Noscapine was chosen as a negative control since there are no reports of photodynamic activity for this drug. Noscapine shares some pharmacophores with berberine and sanguinarine, but lacks the aromatic heterocyclic ring systems of those compounds. Chloroquine is photodynamic but does not produce detectable singlet oxygen under physiological conditions [65, 66]. We were unable to find reports of photodynamic activity for m-AMSA, which has been suggested to damage proteins by a light independent mechanism [67]. Ellipticine has been reported to photo-damage DNA when linked to DNA probes [68], although the mechanism is unclear. Ellipticine has also been reported to enhance the photodynamic production of singlet oxygen by porphyrins when attached to them to cause DNA binding [69].

All of the known singlet oxygen generating photodynamic compounds caused photo-crosslinking of PCNA in our experiments. Chloroquine, which does not generate singlet oxygen, did not cause PCNA photo-crosslinking. m-AMSA was also negative for PCNA photo-crosslinking, possibly for the same reason. Ellipticine was one of the more effective PCNA photo-crosslinking drugs in our study. It appears to have photodynamic activity, at least when binding to DNA [68]. Berberine and palmatine have been reported to generate singlet oxygen through the type II mechanism only when bound to DNA [50], and ellipticine may prove to be similar. Consistent with a role for singlet oxygen, histidine decreased PCNA photo-crosslinking by proflavine, methylene blue, acridine orange, camptothecin, doxorubicin, NPe6 and hypericin. The enhancement of PCNA photo-crosslinking by D2O for proflavine, camptothecin, doxorubicin, NPe6, and hypericin is also consistent with a role for singlet oxygen. Longer incubation of the cells in D2O increased the enhancing effect for proflavine in our study, possibly by replacing more water with time. The fact that prolonged incubation in D2O results in only limited replacement of water has been discussed in relation to limited D2O enhancement of singlet oxygen biological effects [41]. Enhancement of biological endpoints by D2O and suppression by singlet oxygen quenchers is indirect and subject to potential artifacts [70]. The complexities of this approach were also discussed by Ito, who, nevertheless, concluded that the combination of D2O enhancement and singlet oxygen quenchers gives a reasonable qualitative indication of singlet oxygen involvement where endpoints in cells are being studied [41]. The photodynamic crosslinking of PCNA was reduced ~40–50% by flushing of the media with nitrogen, consistent with oxygen dependence.

Treatment of cells with hydrogen peroxide produces highly reactive hydroxyl radicals and other oxidants by the Fenton reaction [71, 72]. Singlet oxygen is not produced from H2O2 by Fenton or Haber-Weiss reactions [71]. Hydrogen peroxide caused only PCNA monoubiquitination, suggesting replication fork arrest from DNA damage [27, 73]. PCNA crosslinking by proflavine and light was not affected by mannitol, ethanol, DMSO, or ascorbate. Ascorbate is a very effective scavenger of hydroxyl radicals, as well as alkoxyl, thiyl, sulfenyl, and other radicals, but it is not a singlet oxygen scavenger [Reviewed in: 74]. DMSO, mannitol and ethanol are specific hydroxyl radical quenchers [75–77]. These results argue against PCNA crosslinking by hydrogen peroxide or hydroxyl radicals. Paraquat, a superoxide generating compound [38], did not produce high molecular weight PCNA forms, and inclusion of superoxide dismutase did not affect PCNA crosslinking by proflavine and light, suggesting that superoxide is not responsible for PCNA crosslinking. The iron chelator and hypoxia inducing agent desferoxamine also had no effect. DTT, a thiol reducing compound had no effect on PCNA photocrosslinking, indicating that crosslinking is not due to disulfide bonds. It has also been argued that His-His crosslinks caused by photodynamic damage are DTT labile [78]. Collectively, these results suggest a role for singlet oxygen in the photodynamic crosslinking of PCNA.

Hypericin and NPe6 caused efficient photo-crosslinking of PCNA in cells, including SV40 infected cells that do not progress to mitosis. Serum in the medium reduced the PCNA damage from NPe6, consistent with published studies showing that NPe6 bind serum proteins, and only NPe6 in excess of serum binding capacity can enter cells [79]. Hypericin uptake and distribution is also known to be affected by the presence or absence of serum in the medium [32]. The pronounced PCNA crosslinking by the cytoplasmically localizing drugs, hypericin and NPe6, was surprising. The short singlet oxygen lifetime (~ 4 µs) restricts diffusion to ~220 nm, less than half the diameter of a mitochondrion [3]. This has given rise to the idea of photodynamic damage localized to sites of drug binding [3, 80]. For drugs localizing in endoplasmic reticulum (hypericin) or lysosomes (NPe6), cell killing would be due to selective singlet oxygen damage to those organelles, and damage to DNA would be minimal. Our results show that cytoplasmically localizing photodynamic drugs can cause significant damage to enzymes localized to the nucleus.

Recently, it was reported that UVA irradiation of cells that have incorporated 6-thioguanine into DNA resulted in crosslinking of PCNA trimers in cells [81]. Our studies with photodynamic drugs detected PCNA oligomerization to at least a tetramer, and crosslinking of PCNA to heterologous proteins. The study with incorporated 6-thioguanine concluded that singlet oxygen was the PCNA crosslinking species, but no tests for singlet oxygen or other ROS were done. Our tests, histidine quenching, D2O enhancement, and negative tests for hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and other ROS suggest a role of singlet oxygen in PCNA crosslinking. In contrast to the results of the 6-thioguanine study, we find that H2O2 and/or hydroxyl radical cause PCNA mono-ubiquitination, but not PCNA crosslinking. PCNA damage from UVA irradiated 6-thioguanine in DNA decreased as replication forks moved away from the sites of incorporation [81]. This, and the absence of PCNA photo-crosslinking from endogenous photosensitizers in our experiments, is consistent with the limited diffusion distances for singlet oxygen, and also argues against PCNA crosslinking by long-lived secondary ROS resulting from singlet oxygen reactions with cellular molecules. PCNA photo-crosslinking by drugs that localize in cytoplasmic structures suggests that traces of these drugs can reach DNA replication forks in sufficient amounts to cause significant photo-damage.

Our original observation of PCNA photo-crosslinking (Fig. 1A) was a laboratory lighting artifact in an experiment investigating PCNA mono-ubiquitination. Photodynamic damage from fluorescence microscopy has been shown to cause artifacts in studies of exocytosis that employ acridine orange [82]. Sanguinarine, a supravital dye for fluorescence microscopy and cytometry [83] was a surprisingly strong PCNA photo-crosslinker. Our study demonstrates the possibility of photodynamic damage to DNA replication and repair enzymes caused by microscopes, flow cytometry lasers, and even laboratory room lighting. Most ROS are capable of damaging not only DNA, but also proteins, including proteins of DNA damage sensing, signaling, and repair [84]. Protein-protein crosslinking is only one aspect of singlet oxygen damage [85], and protein damage from other ROS generated through the type I mechanism is also likely to occur [86]. ROS damage to nuclear enzymes of repair and replication has the potential to alter cell survival, growth, mutagenesis, and carcinogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Tests for light-independent covalent crosslinking of PCNA trimers. CV-1 cells were treated with the drugs at the indicated concentrations as in Fig. 2, but were not exposed to light. The cellular proteins were separated by SDS PAGE and detected by Western blotting with anti-PCNA antibody PC10.

Proflavine, hypericin and NPe6 photo-crosslinking of PCNA trimers in CV-1 cells lytically infected with simian virus 40. CV-1 cells were infected with SV40 (20 plaque-forming units per cell). At the peak of viral DNA replication, 36 hr post-infection, the cells were treated with the drugs indicated (10 µM) and exposed to light in the irradiator (Lt, 7 min, 3.15 J cm−2) or were kept in the dark for 7 min (Dk). Cellular proteins were analyzed by SDS PAGE and Western blotting with anti-PCNA antibody PC10.

Test for type I pathway and other ROS. A. CV-1 cells were treated with 40 µM proflavine and light (3.15 J cm−2) as a control (Ctrl). Other samples were identically treated but included 300 U/ml superoxide dismutase added immediately before treatment with PF and light (SOD) or immediately after treatment (SOD*), 0.1 mM ascorbate (Asc) added for 1 hr (37°C) before treatment, and 50 mM mannitol (Man) added 1 hr before treatment. B. Proflavine control and duplicates of the SOD, SOD*, ascorbate and mannitol experiments in A were included with additional antioxidant tests: 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) added 15 min before treatment, 0.3 mM desferoxamine (DFO) added 6 hr before treatment, 4% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) added 30 min before treatment, and 10 mM ethanol (ETOH) added 30 min before treatment.

Effect of photodynamic damage on electrophoretic behavior of cellular proteins. Proteins from untreated MCF-7 cells and MCF-7 cells exposed to 40 µM proflavine and light (0.9 J cm−2), were compared by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis with Coomassie Blue staining. The black arrowhead indicates the internal protein marker added to the sample before separation (tropomyosin, MWt 33 kDa, pI 6.8). Proteins changed due to photodynamic damage are indicated in the gels from both untreated and treated samples. Areas of increased protein due to proflavine and light treatment are indicated with solid arrows, and areas of decreased protein are indicated with open arrows.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NCI RO1-CA097107 to RMS, and the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30CA16058). We thank Kari Greenchurch and Liwen Zang of the OSU CCIC for help with analysis of proteomic data and preparation of figures, Edith F. Yamasaki for help with editing and Stuart Linn (UC Berkeley) for useful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Castano AP, Demidova TN, Hamblin MR. Mechanisms in photodynamic therapy: part one photosensitizers, photochemistry and cellular localization. Photodiag Photodynam Ther. 2004;1:279–293. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(05)00007-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelik M, et al. Photodynamic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889–905. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redmond RW, Kochevar IE. Spatially resolved cellular responses to singlet oxygen. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82:1178–1186. doi: 10.1562/2006-04-14-IR-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson BW, Dougherty TJ. How does photodynamic therapy work? Photochem Photobiol. 1992;55:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb04222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies KJ, Delsignore ME. Protein damage and degradation by oxygen radicals. III. Modification of secondary and tertiary structure. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:9908–9913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies MJ. Singlet oxygen-mediated damage to proteins and its consequences. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:761–770. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan FH, Saha M, Chakrabarti S. Dopamine induced protein damage in mitochondrial-synaptosomal fraction of rat brain. Brain Res. 2001;895:245–249. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonardi E, Girlando S, Serio G, Mauri FA, Perrone G, Scampini S, et al. PCNA and Ki67 expression in breast carcinoma: correlations with clinical and biological variables. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:416–419. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.5.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Essers J, Theil AF, Baldeyron C, van Cappellen WA, Houtsmuller AB, Kanaar R, et al. Nuclear dynamics of PCNA in DNA replication and repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9350–9359. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9350-9359.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishna TS, Kong XP, Gary S, Burgers PM, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic DNA polymerase processivity factor PCNA. Cell. 1994;79:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuka I, Daidoji H, Matsuoka M, Kadowaki K, Takasaki Y, Nakane PK, et al. Gene for proliferating-cell nuclear antigen (DNA polymerase delta auxiliary protein) is present in both mammalian and higher plant genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3189–3193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenz F, Azzam EI, Little JB. The Response of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen to Ionizing Radiation in Human Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines Is Dependent on p53. Radiat Res. 1998;149:32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naryzhny SN, Desouza LV, Siu KW, Lee H. Characterization of the human proliferating cell nuclear antigen physico-chemical properties: aspects of double trimer stability. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:669–676. doi: 10.1139/o06-037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majka J, Burgers PM. The PCNA-RFC families of DNA clamps and clamp loaders. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2004;78:227–260. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)78006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg P, Burgers PM. Ubiquitinated proliferating cell nuclear antigen activates translesion DNA polymerases eta and REV1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18361–18366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505949102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kannouche PL, Wing J, Lehmann AR. Interaction of human DNA polymerase eta with monoubiquitinated PCNA: a possible mechanism for the polymerase switch in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2004;14:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moldovan GL, Pfander B, Jentsch S. PCNA, the maestro of the replication fork. Cell. 2007;129:665–679. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paunesku T, Mittal S, Protic M, Oryhon J, Korolev SV, Joachimiak A, et al. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): ringmaster of the genome. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77:1007–1021. doi: 10.1080/09553000110069335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snapka RM. The SV40 replicon model for analysis of anticancer drugs. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snapka RM. Papovavirus Models for Mammalian Replicons. In: Snapka RM, editor. The SV40 replicon model for analysis of anticancer drugs. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sclafani RA, Fletcher RJ, Chen XS. Two heads are better than one: regulation of DNA replication by hexameric helicases. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2039–2045. doi: 10.1101/gad.1240604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li D, Zhao R, Lilyestrom W, Gai D, Zhang R, DeCaprio JA, et al. Structure of the replicative helicase of the oncoprotein SV40 large tumour antigen. Nature. 2003;423:512–518. doi: 10.1038/nature01691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uhlmann-Schiffler H, Seinsoth S, Stahl H. Preformed hexamers of SV40 T antigen are active in RNA and origin-DNA unwinding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3192–3201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finley D, Ozkaynak E, Jentsch S, McGrath JP, Bartel B, Pazin M, et al. Molecular genetics of the ubiquitin system. In: Rechsteiner M, editor. Ubiquitin. New York: Plenum; 1996. pp. 39–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Farrell PH. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pappin DJ, Hojrup P, Bleasby AJ. Rapid identification of proteins by peptide-mass fingerprinting. Curr Biol. 1993;3:327–332. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90195-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulrich HD. Deubiquitinating PCNA: a downside to DNA damage tolerance. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:303–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb0406-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watts FZ. Sumoylation of PCNA: Wrestling with recombination at stalled replication forks. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redmond RW, Gamlin JN. A compilation of singlet oxygen yields from biologically relevant molecules. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;70:391–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santamaria L, Prino G. List of the photodynamic substances. Res Prog Org Biol Med Chem. 1972;3(Pt 1):XI–XXXV. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson F, Helman WP, Ross AB. Quantum yields for the photosensitized formation of the lowest electronically excited singlet state of molecular oxygen in solution. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1993;22:113–262. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siboni G, Weitman H, Freeman D, Mazur Y, Malik Z, Ehrenberg B. The correlation between hydrophilicity of hypericins and helianthrone: internalization mechanisms, subcellular distribution and photodynamic action in colon carcinoma cells. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2002;1:483–491. doi: 10.1039/b202884k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiners JJ, Jr, Caruso JA, Mathieu P, Chelladurai B, Yin XM, Kessel D. Release of cytochrome c and activation of pro-caspase-9 following lysosomal photodamage involves Bid cleavage. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:934–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gershey EL. Simian virus 40-host cell interaction during lytic infection. J Virol. 1979;30:76–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.30.1.76-83.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehman JM, Laffin J, Friedrich TD. Simian virus 40 induces multiple S phases with the majority of viral DNA replication in the G2 and second S phase in CV-1 cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2000;258:215–222. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okubo E, Lehman JM, Friedrich TD. Negative regulation of mitotic promoting factor by the checkpoint kinase chk1 in simian virus 40 lytic infection. J Virol. 2003;77:1257–1267. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1257-1267.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naryzhny SN, Zhao H, Lee H. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) may function as a double homotrimer complex in the mammalian cell. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13888–13894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suntres ZE. Role of antioxidants in paraquat toxicity. Toxicology. 2002;180:65–77. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00382-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matheson IB, Etheridge RD, Kratowich NR, Lee J. The quenching of singlet oxygen by amino acids and proteins. Photochem Photobiol. 1975;21:165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1975.tb06647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirasawa K, Amano T, Shioi Y. Effects of scavengers for active oxygen species on cell death by cryptogein. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito T. Cellular and subcellular mechanisms of photodynamic action: the 1O2 hypothesis as a driving force in recent research. Photochem Photobiol. 1978;28:493–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1978.tb06957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder JW, Skovsen E, Lambert JD, Poulsen L, Ogilby PR. Optical detection of singlet oxygen from single cells. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2006;8:4280–4293. doi: 10.1039/b609070m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dean FB, Borowiec JA, Eki T, Hurwitz J. The simian virus 40 T antigen double hexamer assembles around the DNA at the replication origin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14129–14137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavie G, Kaplinsky C, Toren A, Aizman I, Meruelo D, Mazur Y, et al. A photodynamic pathway to apoptosis and necrosis induced by dimethyl tetrahydroxyhelianthrone and hypericin in leukaemic cells: possible relevance to photodynamic therapy. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:423–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim HR, Luo Y, Li G, Kessel D. Enhanced apoptotic response to photodynamic therapy after bcl-2 transfection. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3429–3432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xue LY, Chiu SM, Oleinick NL. Photochemical destruction of the Bcl-2 oncoprotein during photodynamic therapy with the phthalocyanine photosensitizer Pc 4. Oncogene. 2001;20:3420–3427. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henderson BW, Daroqui C, Tracy E, Vaughan LA, Loewen GM, Cooper MT, et al. Crosslinking of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3--a molecular marker for the photodynamic reaction in cells and tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3156–3163. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waseem NH, Lane DP. Monoclonal antibody analysis of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Structural conservation and the detection of a nucleolar form. J Cell Sci. 1990;96(Pt 1):121–129. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fanning E, Knippers R. Structure and function of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:55–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirakawa K, Kawanishi S, Hirano T. The mechanism of guanine specific photooxidation in the presence of berberine and palmatine: activation of photosensitized singlet oxygen generation through DNA-binding interaction. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1545–1552. doi: 10.1021/tx0501740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iwamoto Y, Yoshioka H, Yanagihara Y. Singlet oxygen-producing activity and photodynamic biological effects of acridine compounds. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1987;35:2478–2483. doi: 10.1248/cpb.35.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grebenova D, Halada P, Stulik J, Havlicek V, Hrkal Z. Protein changes in HL60 leukemia cells associated with 5-aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy. Early effects on endoplasmic reticulum chaperones. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;72:16–22. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072<0016:pcihlc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferrario A, Rucker N, Wong S, Luna M, Gomer CJ. Survivin, a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis family, is induced by photodynamic therapy and is a target for improving treatment response. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4989–4995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xue LY, Chiu SM, Oleinick NL. Photochemical destruction of the Bcl-2 oncoprotein during photodynamic therapy with the phthalocyanine photosensitizer Pc 4. Oncogene. 2001;20:3420–3427. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Legrand-Poels S, Bours V, Piret B, Pflaum M, Epe B, Rentier B, et al. Transcription factor NF-kappaB is activated by photosensitization generating oxidative DNA damages. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6925–6934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brunk UT, Dalen H, Roberg K, Hellquist HB. Photo-oxidative disruption of lysosomal membranes causes apoptosis of cultured human fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:616–626. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gabrielli D, Belisle E, Severino D, Kowaltowski AJ, Baptista MS. Binding, aggregation and photochemical properties of methylene blue in mitochondrial suspensions. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;79:227–232. doi: 10.1562/be-03-27.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olmsted J, III, Kearns DR. Mechanism of ethidium bromide fluorescence enhancement on binding to nucleic acids. Biochemistry. 1977;16:3647–3654. doi: 10.1021/bi00635a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brezova V, Valko M, Breza M, Morris H, Telser J, Dvoranova D, et al. Role of radicals and singlet oxygen in photoactivated DNA cleavage by the anticancer drug camptothecin: an electron paramagnetic resonance study. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:2415–2425. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andreoni A, Land EJ, Malatesta V, McLean AJ, Truscott TG. Triplet state characteristics and singlet oxygen generation properties of anthracyclines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;990:190–197. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(89)80033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jantova S, Letasiova S, Brezova V, Cipak L, Labaj J. Photochemical and phototoxic activity of berberine on murine fibroblast NIH-3T3 and Ehrlich ascites carcinoma cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2006;85:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arnason JT, Guerin B, Kraml MM, Mehta B, Redmond RW, Scaiano JC. Phototoxic and photochemical properties of sanguinarine. Photochem Photobiol. 1992;55:35–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duran N, Song PS. Hypericin and its photodynamic action. Photochem Photobiol. 1986;43:677–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1986.tb05646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spikes JD, Bommer JC. Photosensitizing properties of mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 (NPe6): a candidate sensitizer for the photodynamic therapy of tumors. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1993;17:135–143. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(93)80006-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Motten AG, Martinez LJ, Holt N, Sik RH, Reszka K, Chignell CF, et al. Photophysical studies on antimalarial drugs. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;69:282–287. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(1999)069<0282:psoad>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Viola G, Salvador A, Cecconet L, Basso G, Vedaldi D, Dall'Acqua F, et al. Photophysical properties and photobiological behavior of amodiaquine, primaquine and chloroquine. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83:1415–1427. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baguley BC, Wakelin LP, Jacintho JD, Kovacic P. Mechanisms of action of DNA intercalating acridine-based drugs: how important are contributions from electron transfer and oxidative stress? Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:2643–2649. doi: 10.2174/0929867033456332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perrouault L, Asseline U, Rivalle C, Thuong NT, Bisagni E, Giovannangeli C, et al. Sequence-specific artificial photo-induced endonucleases based on triple helix-forming oligonucleotides. Nature. 1990;344:358–360. doi: 10.1038/344358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Milder SJ, Ding L, Etemad-Moghadarn G, Meunier B, Paillous N. Dramatic Enhancement of the Photoactivity of Zinc Porphyrin-Ellipticine Conjugates by DNA. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1990;16:1131–1133. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Foote CS. Detection of singlet oxygen in complex systems: a critique. In: Caughey WS, editor. Biochemical and Clinical Aspects of Oxygen. New York: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 603–626. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Henle ES, Linn S. Formation, prevention, and repair of DNA damage by iron/hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19095–19098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Imlay JA, Chin SM, Linn S. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science. 1988;240:640–642. doi: 10.1126/science.2834821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Friedberg EC. Reversible monoubiquitination of PCNA: A novel slant on regulating translesion DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2006;22:150–152. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carr A, Frei B. Does vitamin C act as a pro-oxidant under physiological conditions? FASEB J. 1999;13:1007–1024. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wasserman HH, Murray RW. Singlet Oxygen. New York: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ranby B, Rabek JF. Singlet oxygen reactions with organic compounds and polymers. New York: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dorfman LM, Adams GE. Reactivity of the Hydroxyl Radical in Aqueous Solutions. No. C13.48:46. National Standard Reference Data Service- National Bureau of Standards. 1973 Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shen HR, Spikes JD, Kopeckova P, Kopecek J. Photodynamic crosslinking of proteins. II. Photocrosslinking of a model protein-ribonuclease A. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1996;35:213–219. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(96)07300-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sheyhedin I, Aizawa K, Araake M, Kumasaka H, Okunaka T, Kato H. The effects of serum on cellular uptake and phototoxicity of mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 (NPe6) in vitro. Photochem Photobiol. 1998;68:110–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.He YY, Council SE, Feng L, Bonini MG, Chignell CF. Spatial distribution of protein damage by singlet oxygen in keratinocytes. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Montaner B, O'Donovan P, Reelfs O, Perrett CM, Zhang X, Xu YZ, et al. Reactive oxygen-mediated damage to a human DNA replication and repair protein. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:1074–1079. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jaiswal JK, Fix M, Takano T, Nedergaard M, Simon SM. Resolving vesicle fusion from lysis to monitor calcium-triggered lysosomal exocytosis in astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14151–14156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704935104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Slaninova I, Slanina J, Taborska E. Quaternary benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloids--novel cell permeant and red fluorescing DNA probes. Cytometry A. 2007;71:700–708. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC. Radical causes of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:276–285. doi: 10.1038/nrc1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davies MJ. Reactive species formed on proteins exposed to singlet oxygen. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:17–25. doi: 10.1039/b307576c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Davies MJ. The oxidative environment and protein damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1703:93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tests for light-independent covalent crosslinking of PCNA trimers. CV-1 cells were treated with the drugs at the indicated concentrations as in Fig. 2, but were not exposed to light. The cellular proteins were separated by SDS PAGE and detected by Western blotting with anti-PCNA antibody PC10.

Proflavine, hypericin and NPe6 photo-crosslinking of PCNA trimers in CV-1 cells lytically infected with simian virus 40. CV-1 cells were infected with SV40 (20 plaque-forming units per cell). At the peak of viral DNA replication, 36 hr post-infection, the cells were treated with the drugs indicated (10 µM) and exposed to light in the irradiator (Lt, 7 min, 3.15 J cm−2) or were kept in the dark for 7 min (Dk). Cellular proteins were analyzed by SDS PAGE and Western blotting with anti-PCNA antibody PC10.

Test for type I pathway and other ROS. A. CV-1 cells were treated with 40 µM proflavine and light (3.15 J cm−2) as a control (Ctrl). Other samples were identically treated but included 300 U/ml superoxide dismutase added immediately before treatment with PF and light (SOD) or immediately after treatment (SOD*), 0.1 mM ascorbate (Asc) added for 1 hr (37°C) before treatment, and 50 mM mannitol (Man) added 1 hr before treatment. B. Proflavine control and duplicates of the SOD, SOD*, ascorbate and mannitol experiments in A were included with additional antioxidant tests: 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) added 15 min before treatment, 0.3 mM desferoxamine (DFO) added 6 hr before treatment, 4% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) added 30 min before treatment, and 10 mM ethanol (ETOH) added 30 min before treatment.

Effect of photodynamic damage on electrophoretic behavior of cellular proteins. Proteins from untreated MCF-7 cells and MCF-7 cells exposed to 40 µM proflavine and light (0.9 J cm−2), were compared by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis with Coomassie Blue staining. The black arrowhead indicates the internal protein marker added to the sample before separation (tropomyosin, MWt 33 kDa, pI 6.8). Proteins changed due to photodynamic damage are indicated in the gels from both untreated and treated samples. Areas of increased protein due to proflavine and light treatment are indicated with solid arrows, and areas of decreased protein are indicated with open arrows.