Levity of heart and neglect of our faults make us insensible to the proper sorrows of the soul.

—Thomas a Kempis1

Sir: Most patients who feel “down in the dumps,” “blue,” or depressed will first see their primary care physician—not a psychiatrist. How that family practitioner or general practitioner sees the patient's complaint—ordinary sadness? major depressive episode?—will have momentous implications for the patient's health and well-being. Now, in their book The Loss of Sadness, Allan V. Horwitz and Jerome C. Wakefield argue that “normal sadness…has three essential components…it is context-specific; it is of roughly proportionate intensity to the provoking loss; and it tends to end about when the loss situation ends…”2(p16) Pathological or “disordered” sadness does not conform to these criteria; it occurs without evident cause or context; it is disproportionate to the provoking loss; and it continues long after the loss situation ends. For millennia, the authors argue, symptoms of sadness that were “with cause” were separated from those that were “without cause.” Only the latter were viewed as mental disorders. With the advent of modern (DSM-III) diagnostic criteria, the authors claim, doctors began to ignore the context of the patient's complaints and focus only on symptoms. Horwitz and Wakefield believe that this “decontextualized” approach has led to a bogus “epidemic” of pseudodepression and overtreatment with antidepressants.

Indeed, the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder deliberately avoid passing judgment on whether a patient's depressive complaints have been triggered by recent losses, with the exception of bereavement (which, somewhat arbitrarily, is limited to a period of 2 months).3 Nor do the DSM-IV criteria attempt to determine whether the patient's sadness is proportionate to some putative triggering event. Instead, the criteria focus on symptoms of suffering and/or incapacity, such as inability to concentrate, insomnia, and impaired social-vocational function. These features must be present for at least 2 weeks. 3

There are compelling reasons why DSM-IV has not adopted the Horwitz-Wakefield thesis. First, their thesis implies that it is fairly easy to determine whether someone with depressive complaints is reacting to a loss that has triggered the depression. Experienced physicians know this is rarely the case. A patient who suffered a stroke one month ago may appear tearful, lethargic, and depressed. Does this represent normal sadness in reaction to a psychological blow, or disruption of mood-regulating monoamine pathways in the brain? Or (more likely), is it a combination of both?

Second, Horwitz and Wakefield want to distinguish evolutionarily appropriate, adaptive “loss responses” from reactions representing malfunction of these loss mechanisms. Thus, they opine that someone “…who becomes deeply depressed after the death of a pet goldfish…” is exhibiting an “overly sensitive, disproportionate loss response [mechanism]…,” barring what they call “special circumstances.”2(p18) To the physician, this conclusion may seem both arbitrary and value laden. Would a patient who becomes deeply depressed after the death of his golden retriever also be exhibiting a disproportionate loss response?

Perhaps most troubling is the implication by Horwitz and Wakefield that the presence of a recent major loss somehow makes it more likely that the person's depressive symptoms will run a benign, time-limited course. To my knowledge, there are no controlled, prospective studies showing that, in a patient who otherwise meets full DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder, the presence of a recent loss reliably predicts a benign course. Neither does the presence of a recent loss mean that antidepressants are necessarily inappropriate (as Horwitz and Wakefield acknowledge). Indeed, work by Zisook and colleagues4 has shown that antidepressants may be helpful in patients with major depressive symptoms occurring shortly after the death of a loved one.

Finally, there is a dimension of depression with which neither the DSM-IV nor the Horwitz-Wakefield thesis comes to grips—the realm of “felt experience” or phenomenology. Generally, when we experience sorrow, we are capable of feeling intimately connected with others. In contrast, when we experience severe depression, we typically feel outcast and alone. Sorrow, to use Martin Buber's terms, is an I-Thou experience,5 whereas clinical depression is a morbid preoccupation with me. (William Styron, in Darkness Visible, describes depressed individuals as having “their minds turned agonizingly inward.”6) When we experience ordinary grief, we usually feel that, someday, it will end. In contrast, severe depression envelops us in the gloom of permanence. Dr. Leston Havens observes that in depression, “…the future is lost, and the past becomes fixed, immovable, bad, the place of irredeemable mistakes.”7 Indeed, the depressed individual often feels that time itself is slowed. This observation has been verified using computerized time-estimation tasks.8,9 Finally, unlike sorrow, severe depression often produces extreme self-deprecation or self-loathing, sometimes of delusional proportions.

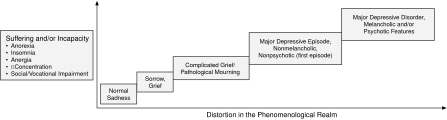

Unipolar depression—which must be carefully distinguished from bipolar depression10––is best understood as lying on a continuum of dysphoric mood states (Figure 1). As we move up the vertical axis, we find increasing suffering and/or incapacity, e.g., impairment in sleep, appetite, energy, concentration, and social-vocational function. As we move from left to right along the horizontal axis, we find increasingly severe distortions in the phenomenological realm. If the patient's suffering and/or incapacity are great, and there is severe distortion in the phenomenological realm, the question of a recent external trigger becomes moot: the patient must be treated. Yes, sadness is a normal part of life, as are “proper sorrows.” And, yes, normal sadness should not be “medicalized,” but neither should suffering and incapacity be “normalized” at the expense of treating a potentially lethal disorder.

Figure 1.

The Depressive Continuum

Ronald Pies, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry, State University of New York (SUNY), Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York

Footnotes

Dr. Pies reports no financial affiliation or other relationship relevant to the subject of this letter.

REFERENCES

- 1.a Kempis T. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 1995. Counsels on the Spiritual Life. Sherley-Price L, trans; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horwitz AV, Wakefield JC. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. The Loss of Sadness. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; p. 327. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zisook S, Shuchter SR, Pedrelli P, et al. Bupropion sustained release for bereavement: results of an open trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(4):227–230. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer KP. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press; 2004. Martin Buber's I and Thou: Practicing Living Dialogue. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Styron W. New York, NY: Vintage; 1992. Darkness Visible: a Memoir of Madness; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havens LL. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1986. Making Contact: Uses of Language in Psychotherapy; p. 21. Cited by: Ghaemi SN. Feeling and time: the phenomenology of mood disorders, depressive realism, and existential psychotherapy. Schizophr Bull 2007;33(1):122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghaemi SN. Feeling and time: the phenomenology of mood disorders, depressive realism, and existential psychotherapy. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(1):122–130. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bschor T, Ising M, Bauer M, et al. Time experience and time judgment in major depression, mania, and healthy subjects: a controlled study of 93 subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109(3):222–229. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghaemi SN, Miller CJ, Berv DA, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a new bipolar spectrum diagnostic scale. J Affect Disord. 2005 Feb;84(2–3):273–277. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]