Abstract

Arginine vasopressin (AVP)-regulated phosphorylation of the water channel aquaporin-2 (AQP2) at serine 256 (S256) is essential for its accumulation in the apical plasma membrane of collecting duct principal cells. In this study, we examined the role of additional AVP-regulated phosphorylation sites in the COOH-terminal tail of AQP2 on protein function. When expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes, prevention of AQP2 phosphorylation at S256A (S256A-AQP2) reduced osmotic water permeability threefold compared with wild-type (WT) AQP2-injected oocytes. In contrast, prevention of AQP2 single phosphorylation at S261 (S261A), S264 (S264A), and S269 (S269A), or all three sites in combination had no significant effect on water permeability. Similarly, oocytes expressing S264D-AQP2 and S269D-AQP2, mimicking AQP2 phosphorylated at these residues, had similar water permeabilities to WT-AQP2-expressing oocytes. The use of high-resolution confocal laser-scanning microscopy, as well as biochemical analysis demonstrated that all AQP2 mutants, with the exception of S256A-AQP2, had equal abundance in the oocyte plasma membrane. Correlation of osmotic water permeability relative to plasma membrane abundance demonstrated that lack of phosphorylation at S256, S261, S264, or S269 had no effect on AQP2 unit water transport. Similarly, no effect on AQP2 unit water transport was observed for the 264D and 269D forms, indicating that phosphorylation of the COOH-terminal tail of AQP2 is not involved in gating of the channel. The use of phosphospecific antibodies demonstrated that AQP2 S256 phosphorylation is not dependent on any of the other phosphorylation sites, whereas S264 and S269 phosphorylation depend on prior phosphorylation of S256. In contrast, AQP2 S261 phosphorylation is independent of the phosphorylation status of S256.

Keywords: water channel, vasopressin, NDI, kidney

aquaporin-2 (AQP2) is a vasopressin-regulated water channel expressed in the principal cells of the kidney collecting duct. In the absence of vasopressin (AVP), AQP2-containing vesicles localize to subapical regions of the cell. Binding of AVP to the basolaterally localized type 2 vasopressin receptor initiates a signaling cascade resulting in increased intracellular cAMP, activation of PKA, phosphorylation of AQP2, and subsequent insertion of the water channel into the apical plasma membrane. This event, rendering the cell more permeable to water, is essential for water reabsorption by the collecting duct and thereby for concentrating the urine. Upon removal of AVP, AQP2 is retrieved from the membrane by endocytosis. Thus the abundance of AQP2 in the apical membrane is a regulated balance between exocytosis and endocytosis.

Protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are common, reversible posttranslational regulatory processes that can regulate the structure and function of numerous proteins, e.g., ion channels (19, 28). In respect to AQP2, phosphorylation of the COOH-terminal tail at serine 256 (S256) is critical for AQP2 accumulation on the apical plasma membrane (6, 15, 30) and in mice, a random mutation resulting in lack of phosphorylation at S256 results in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) (22). Additional phosphorylation sites in the COOH-terminal tail of AQP2 have been identified at serine residues 261 (S261), 264 (S264), and 269 (S269) (10). The abundance of each of these phosphorylated forms of AQP2 is regulated by AVP. Possible roles of these phosphorylation sites have been proposed to be in AQP2 plasma membrane retention (8, 23) and in AQP2 compartmentalization following AVP stimulation (5). A direct effect of polyphosphorylation of the COOH-terminal tail of AQP2 for protein function has not been examined. Phosphorylation-mediated gating of aquaporins has been described in plants. Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of S115 and S274 in the spinach plasma membrane aquaporin SoPIP2;1 regulates water channel activity by either a capping mechanism, or via the opening of a hydrophobic gate (12, 29). Furthermore, pH-dependent gating of AQP0 located within mammalian eye fiber cells has been described (7). Thus phosphorylation-dependent gating of AQP2 to modulate its activity seems an attractive possibility, and has been alluded to previously (16).

In this study, we have used water permeability measurements in the well-characterized Xenopus laevis oocyte expression system, combined with immunocytochemistry and Western blotting to examine the functionality of various phosphorylation-deficient forms of AQP2. Our data demonstrate that the water permeability of AQP2 is unaffected by lack of phosphorylation at S261, S264, and S269 and that the unit water permeability in several mutant forms of AQP2 are identical, suggesting that water permeability of AQP2 is not regulated by gating that is dependent on phosphorylation at these sites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and chemicals.

An antibody recognizing total AQP2 (K5007) directed against the COOH-terminal tail upstream of the S256 phosphorylation site was characterized previously (8). Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies recognizing pS256-AQP2 (25), pS261-AQP2 (9), pS264-AQP2 (5), and pS269-AQP2 (8, 23) have been described previously.

Constructs.

A mouse AQP2 cDNA encoding the full open reading frame cloned into the pcDNA5/FRT vector (Invitrogen) has been described previously (8). Mutations in AQP2 were introduced using site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) and standard methodologies. Mutations preventing phosphorylation of S256, S261, S264, and S269 were obtained by substitution of serine (S) with alanine (A). Mutations mimicking the charge state of AQP2 phosphorylated at the same serine residues were performed by substitution of serine (S) with aspartic acid (D). Mouse AQP2 and mutant forms were subsequently subcloned into the pXOOM vector (11). All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Functional analysis of osmotic water permeability.

Constructs were linearized downstream of the poly(A) segment, in vitro transcribed with T7 mMESSAGE mMACHINE (Ambion, Naerum, Denmark), and the resulting cRNA was purified using MEGAclear (Ambion). Purified cRNA was microinjected into X. laevis oocytes (5 ng RNA/oocyte) collected under anesthesia from frogs that were humanely killed by decapitation after the final collection. The surgical procedures complied with Danish legislation and were approved by the controlling body under the Ministry of Justice. Oocytes were incubated in Kulori medium (90 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) at 19°C for 3–4 days before experiments were performed. The experimental chamber was perfused by a control solution (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Hypertonic test solutions were obtained by adding 20 mosmol/l of mannitol to the control solution. Osmolarities of the test solutions were determined with an accuracy of 1 mosmol/l by a cryoscopic osmometer (Gonotec, Berlin, Germany).

The osmotic water permeability of AQP2-expressing oocytes was measured using an experimental setup that was described in detail previously (33). In short, oocytes were impaled by two microelectrodes filled with 1 mM KCl and were observed from below via a low-magnification objective and focused on at the circumference. The oocyte volume was recorded at a rate of 25 points/s with a noise level of 20 pl/1 μl of oocyte volume. During the experiments, the oocytes were perfused by a control solution (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), and, to measure water permeability, the oocytes were challenged by a hypertonic test solution which was obtained by adding 20 mosmol/l of mannitol to the control solution.

The osmotic water permeability was calculated as LP = −Jv/A × Δπ × Vw, where Jv is the initial water flux during the osmotic challenge, A is the true membrane surface area [about 9 times the apparent area due to membrane foldings (32), around 0.53 cm2], Δπ is the osmotic challenge, and Vw is the partial molal volume of water, 18 cm3/mol. The contribution from the water permeability of the lipid membrane was <10% of the total Lp.

Preparation of oocyte membranes.

Oocyte membranes were purified using a modification of a technique described by Leduc-Nadeau et al. (18). In brief, for the preparation of total membranes, five oocytes were homogenized in 1 ml buffer (HbA+: 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM EDTA, 80 mM sucrose, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.48, and 8 μM leupeptin, and 0.4 mM Pefabloc). Following centrifugation, pellets were resuspended in 20 μl HbA+, 5 μl of 5× sample buffer [7.5% SDS, 250 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 30% glycerol, and 30 mg/ml DTT] was added, and the samples were heated to 65°C for 15 min. For preparation of plasma membranes, 20 oocytes/construct were used. For plasma membranes, unlike the published protocol, samples were centrifuged at 14 g for 30 s, 22 g for 30 s, 31 g for 30 s, and 42 g for 30 s, and at each stage the pellet was kept, resuspended, and centrifuged at the higher speed. A final centrifugation at 17,000 g for 20 min was done to pellet the purified plasma membranes. After removal of the supernatant, the pellets were resuspended in 20 μl HbA+ and 5 μl of 5× sample buffer containing DTT, followed by heating at 65°C for 15 min. Purity of the plasma membrane preparation was confirmed by immunoblotting with an antibody targeting the endoplasmic reticulum marker protein disulfide isomerase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Even after overexposure, there was a complete absence of this major contaminant in the purified plasma membrane fraction (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Immunoblotting.

Total oocyte membranes and purified plasma membranes were subjected to immunoblotting using the K5007 anti-AQP2 antibody (1:50,000). For each construct, 20% of the total purified protein sample was loaded per individual lane. Sites of antibody-antigen reaction were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (GE Healthcare) before exposure to light-sensitive film. Numerous film exposures were performed to be certain that the linearity of the film was not exceeded. The band densities were quantified by densitometry. A minimum of three experiments were performed for each construct.

Immunocytochemistry and confocal laser-scanning microscopy.

A minimum of five oocytes per construct per experiment were fixed for 1 h in 3% paraformaldehyde in Kulori medium, rinsed in Kulori medium, dehydrated in a series of ethanol concentrations (40 min in 70, 96, and 99%) followed by incubation in xylene for 1 h. Oocytes were infiltrated with paraffin for 1 h at 50°C before embedding. Two-micrometer sections were cut on a Leica RM 2126 microtome, and immunostaining was performed as described previously (2). An Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody was used for visualization.

A Leica TCS SL confocal microscope and Leica confocal software were used for imaging of the oocytes. Wild-type (WT) AQP2-expressing oocytes were used to set laser intensity and capture settings on the microscope such that saturation of images for each construct was avoided. The microscope and laser settings were kept constant within each experiment. Images were taken using an HCX PL APO ×63 oil-objective lens. A minimum of one image per oocyte, with five oocytes per experiment, were used for statistical analysis.

Image semiquantification.

AQP2 abundance in the plasma membrane was semiquantified using Leica confocal software. A region of interest (ROI) with fixed dimensions within the plasma membrane was generated, and the pixel intensity within this region and within the whole image frame was recorded. The dimensions of the ROI were kept constant for all images, and the whole frame contained an approximately equal area of oocyte. At a minimum, the pixel values from 1 image from at least 5 oocytes from 3 different experiments were analyzed.

Validation of quantification.

To assess the validity of the methods used throughout the study, an initial pilot study was performed. Oocytes were injected with different quantities of cRNA (0.5–10 ng), and the linearity of the pixel intensity in the ROI and the whole image frame was analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 2). An identical experiment was performed to validate the immunoblotting data (Supplementary Fig. 3). These results confirm that all the measurements were performed using a nonsaturating quantity of cRNA and that saturation of either method used for quantification of membrane abundance was not reached.

Data presentation and statistical analysis.

Quantitative data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparisons test. Multiple-comparisons tests were only applied when a significant difference was determined in the analysis of variance (P < 0.05). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. To facilitate comparisons between studies, in some experiments data are normalized such that the value for WT-AQP2 is 100%.

RESULTS

Analysis of phosphorylation-deficient AQP2 mutants.

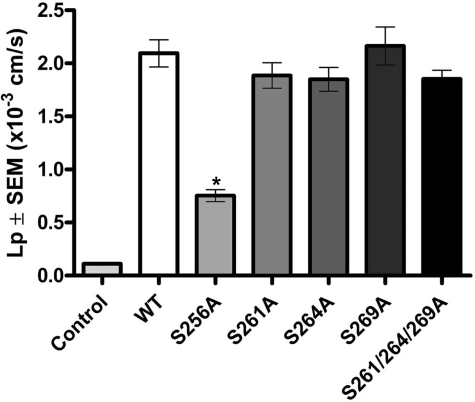

X. laevis oocytes expressing WT-AQP2 or various S-to-A phosphorylation-deficient forms of AQP2 had significantly higher water permeability compared with water-injected control oocytes (Fig. 1). Oocytes expressing S256A-AQP2 had a significantly reduced water permeability compared with WT-AQP2. However, preventing phosphorylation of AQP2 at S261, S264, S269, or S261/S264/S269 combined had no significant effect on water permeability compared with WT-AQP2.

Fig. 1.

Osmotic water permeability (Lp) of oocytes expressing serine-to-alanine mutations of aquaporin-2 (AQP2). A total of 5 oocytes/experiment (n = 4) were injected with 5 ng cRNA encoding wild-type (WT)-AQP2, serine 256 (S256)A-AQP2, S261A-AQP2, S264A-AQP2, S269A-AQP2 or S261A-S264A-S269A-AQP2. The osmotic water permeability of oocytes expressing S256A-AQP2 was significantly lower than WT-AQP2. In contrast, lack of phosphorylation at the other sites had no significant effect on water permeability. Values are means ± SE.. *Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) compared with WT-AQP2.

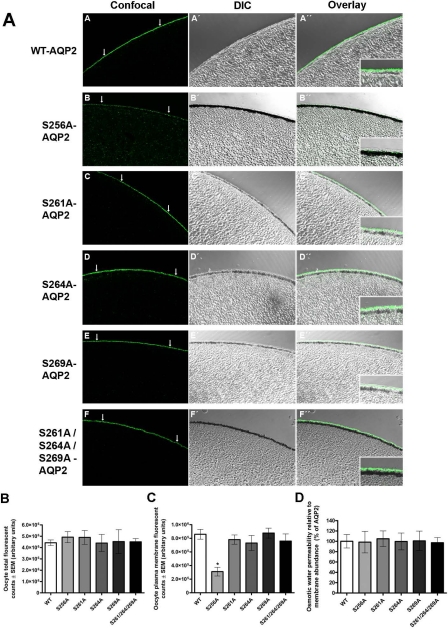

Immunolabeling of oocytes using an anti-AQP2 antibody that recognizes total AQP2 independently of the phosphorylation status of S256, S261, S264, and S269 was performed to assess the relative abundance of each of the protein forms in the oocyte plasma membrane (Fig. 2A). Confocal images and differential interference contrast (DIC) overlays illustrate predominant membrane labeling of oocytes expressing WT, S261A, S264A, S269A, and S261A/S264A/S269A forms of AQP2. In contrast, S256A-AQP2 labeling is observed throughout the oocyte, with the majority of labeling lying just below the plasma membrane. Where plasma membrane labeling is apparent it is punctate in appearance.

Fig. 2.

Immunocytochemistry and relative water permeability of oocytes expressing serine-to-alanine mutations of AQP2. Oocytes were subjected to immunolabeling using an antibody that recognizes total AQP2 independently of the phosphorylation status of S256, S261, S264, and S269. A: confocal images, differential interference contrast (DIC) images, and overlays are shown for the various constructs. B: total fluorescent counts of oocytes including both intracellular and plasma membrane labeling for the various AQP2 forms. Total AQP2 abundance assessed as total fluorescent counts was not significantly different among the AQP2 forms. C: oocyte plasma membrane fluorescent counts were used to assess AQP2 abundance in the plasma membrane. Plasma membrane abundance of S256A-AQP2 was significantly lower compared with WT-AQP2. D: osmotic water permeability relative to plasma membrane abundance was not significantly different between WT-AQP2 and the S-A mutants.

Semiquantification of the immunolabeling showed that the total fluorescent counts corresponding to AQP2 abundance was not different among the various forms of AQP2 examined (Fig. 2B). Oocyte plasma membrane fluorescent counts demonstrated equal plasma membrane abundance of WT, S261A, S264A, S269A, and S261A/S264A/S269A forms of AQP2, whereas the abundance of S256A-AQP2 was significantly lower in the plasma membrane compared with WT-AQP2 (Fig. 2C). To compare the unit water permeability (“single-channel water permeability”) of the different AQP2 forms, the water permeability relative to plasma membrane abundance was calculated (Fig. 2D). Prevention of phosphorylation at S256, S261, S264, S269, and S261/S264/S269 combined had no significant effect on the water transport capacity of AQP2; i.e., when expressed in the plasma membrane of X. laevis oocytes, the water permeability of AQP2 is not affected by phosphorylation.

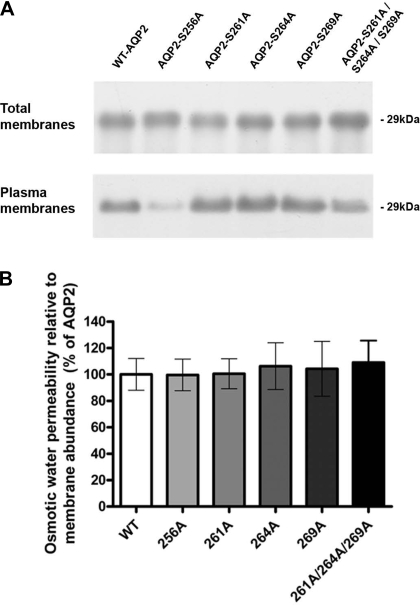

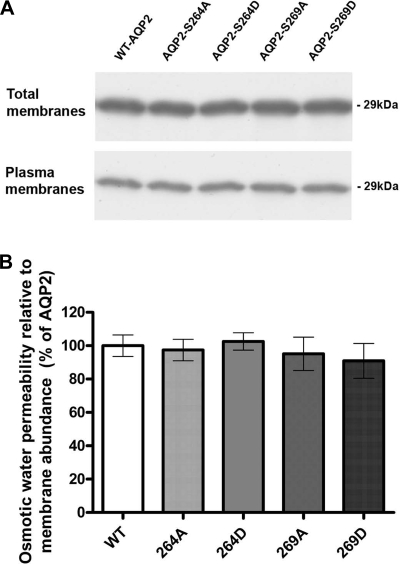

Immunoblotting of oocyte total membrane preparations and plasma membrane preparations using an anti-AQP2 antibody supported these observations (Fig. 3A). In accordance with immunocytochemical observations, densitometry of total membrane preparations revealed that there was no difference in the overall abundance of the AQP2 forms (not shown). Plasma membrane abundance of WT, S261A, S264A, S269A, and S261A/S264A/S269A was not significantly different, whereas the abundance of S256A-AQP2 in the plasma membrane was significantly lower compared with WT-AQP2. Water permeability relative to the membrane abundance assessed by immunoblotting also demonstrated that prevention of phosphorylation does not significantly alter the unit water permeability compared with WT-AQP2 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Immunoblotting of AQP2 in total membrane and plasma membrane purifications of oocytes expressing AQP2. A: representative immunoblot (n = 4). Total AQP2 abundance was not different among the groups as assessed by densitometry (not shown), whereas the plasma membrane abundance of S256A-AQP2 was significantly lower than WT-AQP2. B: osmotic water permeability relative to plasma membrane abundance was not significantly different between WT-AQP2 and the S-A mutants.

Analysis of phosphorylation-mimicking AQP2 mutants.

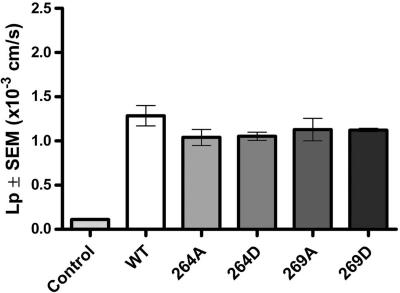

Our previous studies have focused on the regulation of AQP2 by phosphorylation at S264 and S269 (5, 8). In particular, recent studies have determined that pS269-AQP2 is only associated with the apical plasma membrane of collecting duct principal cells, suggesting a vital role in AQP2 regulation (23). To examine these two sites in more detail, we generated constructs mimicking the charge state of AQP2 phosphorylated at position S264 and S269 by point mutations of serine to aspartic acid and expressed the corresponding cRNA in oocytes. The osmotic water permeability of oocytes expressing S264D-AQP2 and S269D-AQP2 were not significantly different from oocytes expressing either WT-AQP2 or the corresponding S-to-A mutants (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Lp of oocytes expressing serine-to-aspartic acid mutations of AQP2. A total of 5 oocytes/experiment (n = 3) were injected with 5 ng cRNA encoding WT-AQP2, S264A-AQP2, S269D-AQP2, S269A-AQP2, or S269D-AQP2. Osmotic water permeability was not significantly different among all the groups. Values are means ± SE.

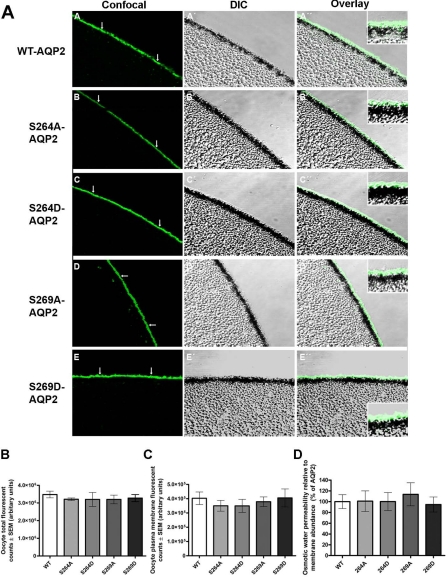

Immunolabeling using an anti-AQP2 antibody showed predominant plasma membrane labeling in both S264D-AQP2- and S269D-AQP2-injected oocytes (Fig. 5A). This labeling was similar to that observed for WT-AQP2, S264A, and S269A mutants. Results of semiquantification of the immunocytochemistry are shown in Fig. 5, B and C. Both total fluorescent counts and plasma membrane fluorescent counts were not significantly different between oocytes expressing WT, S264A, S264D, S269A, and S269D forms of AQP2. Similarly, the water permeability relative to plasma membrane AQP2 abundance was not significantly different among the groups (Fig. 5D). Immunoblotting of oocyte total membrane preparations and plasma membrane preparations using an anti-AQP2 antibody confirmed these observations (Fig. 6). Taken together, these results indicate that “constitutive phosphorylation” of S264 and S269 does not change the water transport capacity of AQP2 expressed in the membrane.

Fig. 5.

Immunocytochemistry and relative water permeability of oocytes expressing serine-to-aspartic acid mutations of AQP2. A: confocal images, DIC images, and overlays are shown for the various constructs. B: total fluorescent counts of oocytes including both intracellular and plasma membrane labeling for the various AQP2 forms. Total AQP2 abundance assessed as total fluorescent counts were not significantly different among the AQP2 forms. C: oocyte plasma membrane fluorescent counts were used to assess AQP2 abundance in the plasma membrane. Plasma membrane abundances were not significantly different among the AQP2 forms. D: osmotic water permeability relative to plasma membrane abundance was not significantly different between WT-AQP2 and the S-D mutants.

Fig. 6.

Immunoblotting of AQP2 in total membrane and plasma membrane purifications of oocytes expressing AQP2. A: representative immunoblot (n = 3). Total AQP2 abundance and plasma membrane abundance was not different among the groups as assessed by densitometry (not shown). B: osmotic water permeability relative to plasma membrane abundance was not significantly different between WT-AQP2 and the S-D mutants.

Phosphorylation events in AQP2.

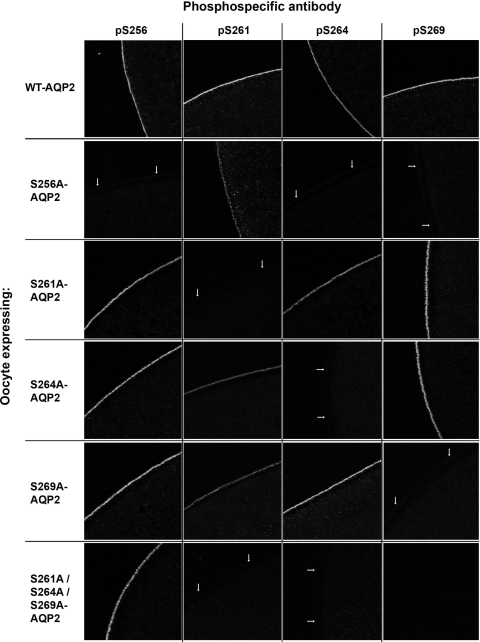

Our previous studies demonstrated that phosphorylation at S264 and S269 is dependant on a prior phosphorylation at S256 (8). To further examine the interdependence of phosphorylation among the various sites, oocytes expressing either WT-AQP2 or phosphorylation-deficient mutants were immunolabeled with four phospho-specific antibodies, pS256-AQP2, pS261-AQP2, pS264-AQP2, and pS269-AQP2. Representative confocal images are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Phosphorylation events in alanine-substituted forms of AQP2 as assessed by immunocytochemistry using phosphospecific antibodies. Confocal images, DIC images, and overlays are shown for oocytes expressing the various cRNAs. In all images, arrows mark the oocyte plasma membrane. All AQP2 phosphoforms were detected in WT-AQP2-expressing oocytes. pS256 labeling was apparent under all conditions (except 256A-AQP2). Neither pS264-AQP2 nor pS269-AQP2 is detected in S256A-AQP2-expressing oocytes. Abundant labeling of pS256, pS264, and pS269 was apparent in S261A-AQP2-expressing oocytes. Weaker labeling of pS261 was detected in both the S264A-AQP2- and S269A-AQP2-expressing oocytes.

All AQP2 phosphoforms were detected in WT-AQP2-expressing oocytes, suggesting that the kinases responsible for the polyphosphorylation are all expressed and functional within the oocyte. pS256 labeling was apparent under all conditions (except 256A-AQP2), suggesting that S256 phosphorylation is not dependent on any of the other phosphorylation sites. Confirming previous observations in vitro and in vivo, neither pS264-AQP2 nor pS269-AQP2 were detected in S256A-AQP2-expressing oocytes; favoring the hypothesis that phosphorylation at these positions depends on prior S256 phosphorylation. Abundant labeling of pS256, pS264, and pS269 was apparent in S261A-AQP2-expressing oocytes, suggesting that phosphorylation of these sites do not depend on pS261. In contrast, weaker labeling of pS261 in both the S264A-AQP2- and S269A-AQP2-expressing oocytes suggests that S261 phosphorylation may depend partially on the phosphorylation status of S264 and S269.

DISCUSSION

Regulation of AQP2 in the collecting duct principal cell includes trafficking to and retrieval from the apical plasma membrane, a process that is tightly regulated by AVP (see Ref. 4). Phosphorylation of the COOH-terminal tail of AQP2 plays a complex regulatory role in trafficking and compartmentalization of the protein (see Ref. 1). Our previous studies have demonstrated that pS261-AQP2 (9), pS264-AQP2 (5), and pS269-AQP2 (8) are localized to some degree in the plasma membrane. Indeed, pS269-AQP2 is exclusively detected in the apical plasma membrane (23), where its abundance is increased several-fold following AVP stimulation, suggesting a possible direct effect of AVP-mediated phosphorylation on AQP2 function. In this study, we examined the water transport function of multiple phosphorylation-deficient AQP2 mutants and address the possibility that phosphorylation of the COOH terminus of AQP2 has a direct effect on water channel permeability.

In our studies, immunoblotting detected both WT, S-A, and S-D-AQP2 mutants as single 29-kDa protein moieties (even after prolonged film exposure). In several AQP2 mutants, resulting in NDI e.g., R187C (14, 21, 24), AQP2 is presented as both native 29-kDa and high-mannose 32-kDa protein moieties. The 32-kDa form is indicative of improper folding of the mutant, resulting in a lack of removal of the high-mannose sugar groups in the early cis-Golgi complex. The single 29-kDa band we observe suggests that, within oocytes, all phosphorylation-deficient mutants fold correctly.

AQP2 mutants lacking phosphorylation at S261, S264, and S269, or all three sites combined, had water permeabilities similar to WT controls. Importantly, in our studies the amount of cRNA injected did not result in a quantity of protein that saturated the normal transport and storage machinery of the oocyte, or endocytic retrieval pathways. This is highlighted by the apparent reduction in the water permeability of S256A-injected oocytes compared with WT-injected controls. Previous studies have demonstrated that when expressed in oocytes at saturating levels of cRNA, S256A-AQP2 has a similar water permeability to WT-AQP2 (24), whereas under nonsaturating conditions its water permeability is much lower (13, 16), in line with our observations.

A combination of immunocytochemistry and confocal laser-scanning microscopy, alongside immunoblotting of purified oocyte plasma membranes, demonstrated that all phosphorylation-deficient mutants, except S256A-AQP2, are detectable in the oocyte plasma membrane. In the case of S256A-AQP2, immunoblotting showed an approximately threefold lower abundance of AQP2 in plasma membrane fractions. Furthermore, immunocytochemistry showed that the S256A mutant was localized to a subapical domain. In agreement with this, Kamsteeg and colleagues (13) demonstrated a similar phenomenon in oocytes expressing S256A-AQP2, and AVP stimulation had no effect on localization of S256A-AQP2 in transfected cells (6, 15). Recent studies from the Brown laboratory (26) have suggested that phosphorylation of AQP2 at S256 plays only a small role in AVP-mediated translocation of AQP2, but in contrast is directly involved in constitutive AQP2 exocytosis. Further studies are required to determine whether S256 phosphorylation is essential for AVP-mediated AQP2 translocation, or whether phosphorylation at this site is necessary for plasma membrane retention of AQP2.

Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are known to be a common molecular mechanism in proteins resulting in modulation of protein function (3). Several channels and pumps are known to be regulated by phosphorylation. For example, phosphorylation of the voltage-gated sodium channel has been proposed to play a role in altering channel kinetics by changing activation and inactivation rates of the protein (28); transient receptor potential channel activity is regulated by both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation (31); and phosphorylation can alter the open channel probability of numerous potassium channels (27). Phosphorylation-mediated gating of aquaporins has been described in plants (12, 29). In contrast, our studies demonstrate conclusively that removing phosphorylation at S256, S261, S264, or S269 at the COOH-terminal tail of AQP2 has no significant effect on the unit water permeability of AQP2. Additionally, mimicking constitutive phosphorylation at S264 or S269 (S-to-D mutation) has no effect on osmotic water permeability, indicating that AQP2 activity in the plasma membrane is not affected by an alteration in the charge state of its COOH-terminal tail. Previous studies have concentrated on the effect of phosphorylation at S256 on AQP2 water permeability. For example, Kamsteeg et al. (13) showed that S256D-AQP2-expressing oocytes have similar water permeability to WT-AQP2 when expressed at equal abundances in the plasma membrane. Additionally, PKA-dependent phosphorylation of AQP2 in purified endosomes (presumably at S256, as this is the only site directly phosphorylated by PKA) (8), had no effect on single-channel water permeability (17). Taken together, we conclude that phosphorylation of the COOH-terminal tail of AQP2 does not directly affect its water transport function, indicating that AQP2 is not gated by phosphorylation.

Expression of aquaporins heterologously in X. laevis oocytes, with minimal interference from other transport proteins, is a well-characterized system for studying channel function. However, the system it is not without limitations. For example, X. laevis oocytes are kept at 19 or 20°C, and a mutant mammalian channel, e.g., aquaporin, whose trafficking or function is defective only at higher temperatures (37°C), may display a normal phenotype when expressed in frog oocytes. Additionally, it is plausible that mammalian accessory proteins that bind to the phosphorylated tail of AQP2 and regulate its function are not present in the frog oocyte. Examination of AQP2 regulation by polyphosphorylation in a polarized cell model would help to clarify some of these possibilities.

We have previously demonstrated that PKA-mediated phosphorylation of AQP2 at S256 is a hierarchal phosphorylation event that is required for further downstream phosphorylation of the tail of AQP2. This was confirmed in the current study, where neither pS264-AQP2 nor pS269-AQP2 was detected in S256A-AQP2-expressing oocytes. Additionally, in this study we demonstrate that S256 phosphorylation is not dependent on any of the other phosphorylation sites, further supporting the view that S256 phosphorylation occurs first. Interestingly, pS261-AQP2 was detected in S256A-AQP2-expressing oocytes, suggesting that S261 phosphorylation is independent of the phosphorylation status of S256. Since the effects of S256 phosphorylation on AQP2 trafficking seem to be dominant over S261 phosphorylation (20), the role of S261 in AQP2 function remains to be determined. Previous studies have failed to determine the kinases responsible for the phosphorylation at S261, S264, or S269 (8). Our current studies suggest that, as phosphorylation of S269 occurs in S264A-AQP2 mutants, S264 phosphorylation is not a priming event for S269 phosphorylation. Alternatively, as a lack of S261 phosphorylation has no effect on pS264, the involvement of a primed kinase, e.g., CK1, that could phosphorylate S261 priming phosphorylation of S264 by the same kinase seems unlikely.

In summary, our studies using a heterologous expression system demonstrate that phosphorylation of S261, S264, or S269 in the COOH-terminal tail of AQP2 does not directly alter the water transport function of AQP2. Additionally, the unit water permeability of several phosphorylation-deficient mutant forms of AQP2, including S256A, are identical, suggesting that water permeability of AQP2 is not regulated by gating that is dependent on phosphorylation of the COOH-terminal tail. Further studies are required to determine the role of distinct COOH-terminal polyphosphorylation for AQP2 regulation.

GRANTS

R. A. Fenton is supported by a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship. H. B. Moeller is supported by the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Aarhus. The Water and Salt Research Center at the University of Aarhus is established and supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (Danmarks Grundforskningsfond). Additional funding was provided by the EU 7th Framework (to R. A. Fenton), the Danish Medical Research Council (to R. A. Fenton and N. MacAulay), the Lundbeck Foundation (to N. MacAulay), the E. Danielsen Foundation (to N. MacAulay), and The Nordic Centre of Excellence Program (NCoE) in Molecular Medicine (to R. A. Fenton and N. MacAulay). Funding to M. A. Knepper was provided by the Intramural Budget of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (National Institutes of Health Project ZO1-HL-001285).

Acknowledgments

We thank Inger Merete Paulsen, Tove Soland, and Charlotte G. Iversen for expert technical assistance. We are grateful to Jeppe Praetorius for discussions on confocal quantification.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown D, Hasler U, Nunes P, Bouley R, Lu HA. Phosphorylation events and the modulation of aquaporin 2 cell surface expression. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 491–498, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen BM, Wang W, Frøkiær J, Nielsen S. Axial heterogeneity in basolateral AQP2 localization in rat kidney: effect of vasopressin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F701–F717, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen P The regulation of protein function by multisite phosphorylation—a 25 year update. Trends Biochem Sci 25: 596–601, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenton RA, Moeller HB. Recent discoveries in vasopressin-regulated aquaporin-2 trafficking. Prog Brain Res 170: 571–579, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton RA, Moeller HB, Hoffert JD, Yu MJ, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Acute regulation of aquaporin-2 phosphorylation at Ser-264 by vasopressin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3134–3139, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fushimi K, Sasaki S, Marumo F. Phosphorylation of serine 256 is required for cAMP-dependent regulatory exocytosis of the aquaporin-2 water channel. J Biol Chem 272: 14800–14804, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedfalk K, Tornroth-Horsefield S, Nyblom M, Johanson U, Kjellbom P, Neutze R. Aquaporin gating. Curr Opin Struct Biol 16: 447–456, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffert JD, Fenton RA, Moeller HB, Simons B, Tchapyjnikov D, McDill BW, Yu MJ, Pisitkun T, Chen F, Knepper MA. Vasopressin-stimulated increase in phosphorylation at Ser269 potentiates plasma membrane retention of aquaporin-2. J Biol Chem 283: 24617–24627, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffert JD, Nielsen J, Yu MJ, Pisitkun T, Schleicher SM, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Dynamics of aquaporin-2 serine-261 phosphorylation in response to short-term vasopressin treatment in collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F691–F700, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffert JD, Pisitkun T, Wang G, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Quantitative phosphoproteomics of vasopressin-sensitive renal cells: regulation of aquaporin-2 phosphorylation at two sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7159–7164, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jespersen T, Grunnet M, Angelo K, Klaerke DA, Olesen SP. Dual-function vector for protein expression in both mammalian cells and Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biotechniques 32: 536–538, 540, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansson I, Karlsson M, Shukla VK, Chrispeels MJ, Larsson C, Kjellbom P. Water transport activity of the plasma membrane aquaporin PM28A is regulated by phosphorylation. Plant Cell 10: 451–459, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamsteeg EJ, Heijnen I, van Os CH, Deen PM. The subcellular localization of an aquaporin-2 tetramer depends on the stoichiometry of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated monomers. J Cell Biol 151: 919–930, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamsteeg EJ, Wormhoudt TA, Rijss JP, van Os CH, Deen PM. An impaired routing of wild-type aquaporin-2 after tetramerization with an aquaporin-2 mutant explains dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. EMBO J 18: 2394–2400, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsura T, Gustafson CE, Ausiello DA, Brown D. Protein kinase A phosphorylation is involved in regulated exocytosis of aquaporin-2 in transfected LLC-PK1 cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 272: F817–F822, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuwahara M, Fushimi K, Terada Y, Bai L, Marumo F, Sasaki S. cAMP-dependent phosphorylation stimulates water permeability of aquaporin-collecting duct water channel protein expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 270: 10384–10387, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lande MB, Jo I, Zeidel ML, Somers M, Harris HW Jr. Phosphorylation of aquaporin-2 does not alter the membrane water permeability of rat papillary water channel-containing vesicles. J Biol Chem 271: 5552–5557, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leduc-Nadeau A, Lahjouji K, Bissonnette P, Lapointe JY, Bichet DG. Elaboration of a novel technique for purification of plasma membranes from Xenopus laevis oocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C1132–C1136, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levitan IB Modulation of ion channels by protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Annu Rev Physiol 56: 193–212, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu HA, Matsuzaki T, Bouley R, Hasler U, Qin QH, Brown D. The phosphorylation state of serine 256 is dominant over that of serine 261 in the regulation of AQP2 trafficking in renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F290–F294, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marr N, Kamsteeg EJ, van Raak M, van Os CH, Deen PM. Functionality of aquaporin-2 missense mutants in recessive nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Pflügers Arch 442: 73–77, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDill BW, Li SZ, Kovach PA, Ding L, Chen F. Congenital progressive hydronephrosis (cph) is caused by an S256L mutation in aquaporin-2 that affects its phosphorylation and apical membrane accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 6952–6957, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moeller HB, Knepper MA, Fenton RA. Serine 269 phosphorylated aquaporin-2 is targeted to the apical membrane of collecting duct principal cells. Kidney Int 75: 295–303, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulders SM, Bichet DG, Rijss JP, Kamsteeg EJ, Arthus MF, Lonergan M, Fujiwara M, Morgan K, Leijendekker R, van der Sluijs P, van Os CH, Deen PM. An aquaporin-2 water channel mutant which causes autosomal dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is retained in the Golgi complex. J Clin Invest 102: 57–66, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimoto G, Zelenina M, Li D, Yasui M, Aperia A, Nielsen S, Nairn AC. Arginine vasopressin stimulates phosphorylation of aquaporin-2 in rat renal tissue. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F254–F259, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nunes P, Hasler U, McKee M, Lu HA, Bouley R, Brown D. A fluorimetry-based ssYFP secretion assay to monitor vasopressin-induced exocytosis in LLC-PK1 cells expressing aquaporin-2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C1476–C1487, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park KS, Yang JW, Seikel E, Trimmer JS. Potassium channel phosphorylation in excitable cells: providing dynamic functional variability to a diverse family of ion channels. Physiology (Bethesda) 23: 49–57, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz DJ, Temporal S, Barry DM, Garcia ML. Mechanisms of voltage-gated ion channel regulation: from gene expression to localization. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 2215–2231, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tornroth-Horsefield S, Wang Y, Hedfalk K, Johanson U, Karlsson M, Tajkhorshid E, Neutze R, Kjellbom P. Structural mechanism of plant aquaporin gating. Nature 439: 688–694, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Balkom BW, Savelkoul PJ, Markovich D, Hofman E, Nielsen S, van der Sluijs P, Deen PM. The role of putative phosphorylation sites in the targeting and shuttling of the aquaporin-2 water channel. J Biol Chem 277: 41473–41479, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao X, Kwan HY, Huang Y. Regulation of TRP channels by phosphorylation. Neurosignals 14: 273–280, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zampighi GA, Kreman M, Boorer KJ, Loo DD, Bezanilla F, Chandy G, Hall JE, Wright EM. A method for determining the unitary functional capacity of cloned channels and transporters expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J Membr Biol 148: 65–78, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeuthen T, Belhage B, Zeuthen E. Water transport by Na+-coupled cotransporters of glucose (SGLT1) and of iodide (NIS). The dependence of substrate size studied at high resolution. J Physiol 570: 485–499, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]