Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Study is a 16-center randomized clinical trial in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes designed to evaluate the long-term effects (up to 11.5 years) of an intensive weight loss intervention on the time to incidence for major cardiovascular events.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Eligibility requirements are diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (determined by self-report and verification) in individuals age 45–74 years, BMI >25 kg/m2 (>27 kg/m2 if currently taking insulin). The intensive lifestyle intervention is designed to achieve and maintain weight loss through decreased caloric intake and increased physical activity. The study is designed to provide 90% probability of detecting an 18% difference in major cardiovascular disease event rates in patients randomized to the intensive lifestyle intervention compared to the control group receiving standard diabetes support and education.

RESULTS

The 5145 participants who were randomized between 2001 and 2004 were 63.3 % white, 15.6% African-American, 13.2% Hispanic, 5.1% American Indian, and 1.0% Asian-American, which closely paralleled the ethnic distribution of diabetes in the NHANES 1999–2000 survey. Their average age at entry was 59 ± 6.8 years (mean ± SD), and 60% were women. There were 31.5% between 45-54 years of age, 51.5% were 55–64, and 17.0% ≥65 years of age. There were 14.6% of participants who were taking insulin at the time of randomization and 14.1 % had a history of cardiovascular disease. More men (21.2%) than women (9.3%) had a history of cardiovascular disease. Few participants (4.4%) were current cigarette smokers compared to 16.2% in the NHANES 1999–2000 survey. Furthermore, 65% of participants had a first-degree relative with diabetes. Overall, BMI averaged 36 ± 5.9 kg/m2 at baseline with 83.6% of the men and 86.0% of women having a BMI >30 kg/m2 and 17.9% of men and 25.4% of women having a BMI > 40 kg/m2.

CONCLUSIONS

The Look AHEAD study has successfully randomized a large cohort of participants who have type 2 diabetes with a wide distribution of age, obesity, ethnicity and racial background.

Introduction

Look AHEAD is a randomized clinical trial being conducted in 16 centers in the U.S. The purpose of the Look AHEAD trial is to determine whether cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in persons with type 2 diabetes can be reduced through an intensive lifestyle intervention aimed at producing and maintaining weight loss. Briefly the intensive lifestyle intervention includes moderate-intensity physical activity to achieve and sustain at least 200 min per week of exercise together with a healthy diet that includes portion-controlled foods (3). The goal of this intervention is for individuals to achieve and maintain at least 10% loss of body weight. Failure to meet appropriate goals is followed by the option of initiating other ‘toolbox’ strategies (e.g., medication for weight loss). The intensive lifestyle intervention is delivered over 4 years and participants are followed for up to 11.5 years. The control condition is termed “Diabetes Support and Education” which is comprised of occasional group meetings to provide social support and education regarding diabetes management. All participants continue to receive medical management of their diabetes from their usual source of medical care, not from the Look AHEAD medical staff. The design and methods for this trial have been described fully elsewhere (2).

This report presents the baseline demographic and biomedical characteristics of the Look AHEAD participants that were measured at entry. We compared the Look AHEAD participants to those in the general U.S. population, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III and NHANES 1999–2000 (4, 5).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Participants

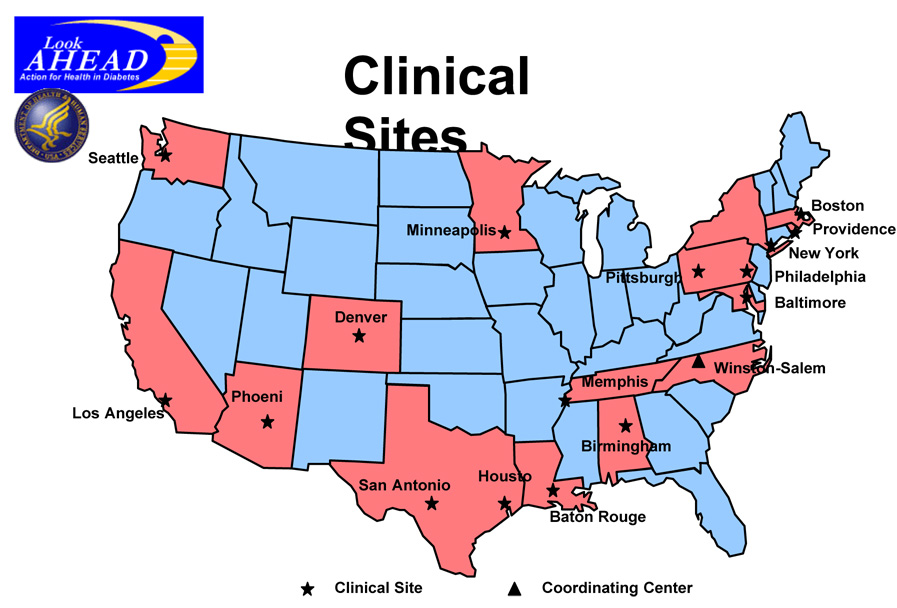

Individuals were recruited from a variety of sources including informational mailings, open screenings, advertisements, and referrals from health care professionals. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before screening, consistent with the Helsinki Declaration and the guidelines of each center’s institutional review board. Individual consent procedures were used for each step of the study. During screening, individuals who had urgent medical conditions or values for HbA1c, triglycerides, creatinine, or blood pressure that exceeded eligibility limits could be re-screened after 3 months of medical care. All participant underwent a graded maximal exercise test to confirm that, if randomized to the lifestyle intervention this could be tolerated and considered safe and also to allow development of an appropriate, individualized exercise prescription (3, 6). The locations of the 16 field centers and the coordinating center are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map of the Look AHEAD Coordinating Center, NIH Site and the 16 Field Centers.

Additional inclusion criteria were age 45–74 years, which was changed to 55–74 years during year 2 to increase the anticipated cardiovascular event rate, and a BMI >25 kg/m2 (>27 kg/m2, if currently taking insulin). Major exclusions included HbA1c ≥11%, blood pressure ≥ 160/100 mmHg, triglycerides ≥ 600 mg/dl, inadequate control of co-morbid conditions, factors that may limit adherence to the intervention protocol, or may affect conduct of the trial, and underlying disease likely to limit lifespan and/or affect safety of the interventions. It was anticipated that 20–30% of enrollees would have pre-existing cardiovascular disease and about 30% would be taking insulin at entry into the study. The goal was to recruit equal numbers of men and women and to have 33% of the participants from racial and ethnic minority groups.

All study participants were required to complete a two-week run-in period prior to randomization which required successful self-monitoring of diet and physical activity.

Procedures

Blood samples were collected and processed at baseline according to protocol. Each Look AHEAD clinical site followed the standardized manual of operations (2, 3). Whole-blood samples for HbA1c analysis were shipped to the Look AHEAD Central Biochemistry Laboratory (Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories, University of Washington, Seattle WA) by overnight express within 24 h of sample collection. Other serum and plasma samples were stored at <20°C for a few days and then shipped on dry ice in batches to the central laboratory.

Standardized interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to obtain self-reported data on personal medical history, employment, education, family income, prior pregnancies, smoking, prescription medications, alcohol use, and family medical history (2). Race/ethnicity was self-reported using the questions from the 2000 U.S. Census questionnaire. Additionally, dietary intake, body fat distribution, and physical activity levels at baseline were assessed in substudies at some of the centers, but they are not reported here. Clinic staff were certified in the measurement of body size measures and blood pressure. Weight was measured in duplicate on a digital scale. Standing height was determined in duplicate with a standard stadiometer. The waist circumference was measured with subjects in light clothing with a non-metallic, constant tension tape placed around the body at midpoint between the highest point of the iliac crest and lowest part of the costal margin in the mid-axillary line. Seated blood pressure was measured in duplicate with an automated device. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg, or use of anti-hypertensive medications. An ankle brachial index (ABI) was calculated by dividing the ankle systolic blood pressure by the arm systolic blood pressure. Blood pressures for the ABI were obtained using a continuous wave Doppler system and a standard mercury sphygmomanometer.

Measurements

All analytical measurements were performed at the Look AHEAD Central Biochemistry Laboratory. HbA1c was measured by a dedicated ion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography instrument (Biorad Variant II). Fasting plasma glucose was measured by the glucokinase method and creatinine in serum was measured by the Jaffa rate blanked method on the Hitachi 917 chemistry autoanalyzer. Measurements of total plasma cholesterol, and triglycerides were performed enzymatically (7) using methods standardized to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Reference Methods. HDL fractions for cholesterol analysis were obtained by the treatment of whole plasma with dextran sulfate-Mg+2 to precipitate all of the apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins (8). LDL cholesterol was calculated by the equation of Friedewald et al. (9). In participants with triglycerides >4.5 mmol/L, the lipoprotein fractions were separated by preparative ultracentrifugation of plasma (10). Aliquots of serum and plasma samples were collected and stored frozen at- 70 C for future analyses. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Data management and analyses

Locally generated data from each participant were entered into an internet based data entry system by certified staff at each clinical site. The system checked for allowed ranges and internal consistency at the time of data entry; further checks were conducted in batches by the Look AHEAD Coordinating Center (CoC). Data from the central resource units (the Biochemistry Laboratory and the ECG reading center) were transferred electronically to the CoC. The central database was maintained, and all analyses were performed at the CoC using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Baseline characteristics of randomized participants were examined by treatment group assignment, sex, and race/ethnicity (Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, American Indian, Asian-American, and other). Comparisons of the prevalence of medication use across race/ethnicity, age, education, and income categories were made after adjustment for these characteristics using logistic regression. Look AHEAD data were also compared with the weighted NHANES III (1988–1994) and NHANES 1999–2000 data for those participants matching the major eligibility criteria (4, 5).

RESULTS

Clinical and demographic characteristics

More than 27,000 individuals underwent screening across the study centers. Of these, 5145 people were ultimately randomized, with 2570 participants in the intensive lifestyle intervention cohort and 2575 in the diabetes support and education cohort. Table 1 shows the overall distribution of baseline characteristics of the participants in Look AHEAD by treatment group assignment. The overall mean (± SD) age at randomization was 59 ± 6.8 years. Nearly 60% of the participants were women and nearly 40% of the participants belonged to a U.S. minority racial or ethnic group; 63.3% were White, 15.6% African-American, 13.2% Hispanic, 5.1% American Indian, and 1% Asian-American (Table 2). Less than 2% reported another race group, more than one race, or did not respond to this question (referred to as ‘other’). On all of the other variables, including body composition, diabetes control, plasma lipid levels, blood pressure, duration of diabetes mellitus, fitness, prevalence of the metabolic syndrome, and family history of diabetes mellitus, the groups were well matched.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by randomized intervention assignment.

| Variable | Diabetes Support And Education | Lifestyle Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 2575 | 2570 |

| Age (yrs) | 58.85 ± 6.86 | 58.55 ± 6.77 |

| Sex (%F) | 1534 (59.6%) | 1524 (59.3%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African American / Black | 405 (15.8%) | 398 (15.5%) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 129 (5.0%) | 131 (5.1%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 21 (0.8%) | 29 (1.1%) |

| White | 1628 (63.4%) | 1618 (63.1%) |

| Hispanic | 337 (13.1%) | 338 (13.2%) |

| Other | 49 (1.9%) | 49 (1.9%) |

| Weight (kg) | 100.86 ± 18.83 | 100.54 ± 19.65 |

| Height (cm) | 167.27 ± 9.86 | 167.22 ± 9.59 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 36.00 ± 5.76 | 35.89 ± 6.01 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 114.06 ± 13.55 | 113.80 ± 14.35 |

| Ankle/Brachial Index (minimum) | 1.07 ± 0.26 | 1.07 ± 0.26 |

| Hemoglobin A1c% | 7.31 ± 1.20 | 7.25 ± 1.14 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 154.04 ± 46.50 | 152.19 ± 44.71 |

| Plasma creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.82 ± 0.20 | 0.82 ± 0.20 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190.65 ± 37.04 | 191.33 ± 38.16 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 112.23 ± 32.30 | 112.36 ± 32.21 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 43.47 ± 11.81 | 43.48 ± 11.83 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 179.94 ± 117.92 | 181.96 ± 117.69 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 129.45 ± 17.09 | 128.19 ± 17.26 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 70.40 ± 9.72 | 69.93 ± 9.55 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 6.82 ± 6.42 | 6.77 ± 6.66 |

| Fitness | ||

| Maximal MET Value | 7.18 ± 1.99 | 7.21 ± 1.95 |

| Maximal MET Value (at 80% HR) | 5.10 ± 1.54 | 5.17 ± 1.53 |

| Metabolic Syndrome, n (%) | 2415 (93.8%) | 2387 (92.9%) |

| Family history of diabetes, n (%) | 1723 (66.9%) | 1622 (63.1%) |

| History of CVD, n (%) | 353 (13.7%) | 373 (14.5%) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2069 (80.3%) | 2063 (80.3%) |

Table 2.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics by sex.

| Overall | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 5145 | 2087 | 3058 |

| Age (yrs) | |||

| 1620 (31.5%) | 527 (25.3%) | 1093 (35.8%) | |

| 2650 (51.5%) | 1116 (53.5%) | 1534 (50.2%) | |

| 874 (17.0%) | 444 (21.3%) | 430 (14.1%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| African American / Black | 804 (15.7%) | 190 (9.1%) | 614 (20.1%) |

| American Indian / Alaskan Native | 259 (5.0%) | 55 (2.6%) | 204 (6.7%) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 50 (1.0%) | 16 (0.8%) | 34 (1.1%) |

| White | 3244 (63.2%) | 1580 (76.0%) | 1664 (54.5%) |

| Hispanic | 676 (13.2%) | 196 (9.4%) | 480 (15.7%) |

| Other | 99 (1.9%) | 42 (2.0%) | 57 (1.9%) |

| Employment Status, n (%) | |||

| Full or part-time | 3232 (71.2%) | 1395 (80.7%) | 1837 (65.4%) |

| Homemaker | 905 (19.9%) | 133 (7.7%) | 772 (27.5%) |

| Full or part-time student | 20 (0.4%) | 4 (0.2%) | 16 (0.6%) |

| Not employed | 380 (8.4%) | 196 (11.3%) | 184 (6.6%) |

| Education (years) | |||

| < 13 years | 1024 (20.4%) | 261 (12.7%) | 763 (25.6%) |

| 13 – 16 years | 1911 (38.0%) | 695 (33.9%) | 1216 (40.8%) |

| > 16 years | 2093 (41.6%) | 1094 (53.4%) | 999 (33.5%) |

| Any alcohol in past year, n (%) | 3069 (59.7%) | 1470 (70.4%) | 1599 (52.3%) |

| Family Income (1000’s) | |||

| < $20 | 589 (12.7%) | 137 (7.2%) | 452 (16.6%) |

| $20 – $40 | 984 (21.2%) | 259 (13.6%) | 725 (26.6%) |

| $40 – $60 | 953 (20.6%) | 346 (18.1%) | 607 (22.3%) |

| $60 – $80 | 751 (16.2%) | 339 (17.8%) | 412 (15.1%) |

| > $80 | 1359 (29.3%) | 827 (43.3%) | 532 (19.5%) |

| Smoking Status, n (%) | |||

| Never | 2575 (50.2%) | 781 (37.6%) | 1794 (58.8%) |

| Past | 2327 (45.4%) | 1201 (57.8%) | 1126 (36.9%) |

| Present | 228 (4.4%) | 96 (4.6%) | 132 (4.3%) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |||

| Never married | 386 (7.5%) | 118 (5.7%) | 268 (8.8%) |

| Married / Marriage-like relationship | 3460 (67.3%) | 1731 (83.1%) | 1729 (56.6%) |

| Widowed | 359 (7.0%) | 36 (1.7%) | 323 (10.6%) |

| Divorced / Separated | 934 (18.2%) | 199 (9.5%) | 735 (24.1%) |

Table 2 shows the distribution of demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the Look AHEAD participants by gender. The females were younger than the males with 35.8% of females vs 25.3% of males being 45–55 years old and 14.1% of females and 21.3% of males being 65–75 years old. While 60% of the overall cohort was female, there were many more females in the minority groups (e.g., 76% of the African American participants were female). Over 80% of the males and 65% of the females were employed. The educational level was high with more than 50% of the men and 33% of the women having more than 16 years in school. Alcohol intake in the past year was reported by just under 60% of the population with its prevalence higher in males than females (70% to 52%). Family income was higher among the men with over 40% reporting an income >$80,000/year compared with just under 20% for the women. Nearly 60% of the women and 38% of the men had never smoked, and just over 4% were currently smoking. Over 83% of the men and 56% of the women were married or living in a marriage-like relationship.

Clinical characteristics of the Look AHEAD participants divided by gender and racial/ethnic group are shown in Table 3 & Table 4. There were relatively few Asian/American men (N=16) and women (N=34). The frequency of prior pregnancy was ranged between 85.6% and 94.7%, except in the Asian-American women where it was 73.5%. Caucasian participants were generally the oldest participants in the cohort, and American Indians, the youngest. Similar percentages of women and men were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2), and more than 25% of the women, except Hispanic and Asian/American women, had a BMI > 40 kg/m2. Among the men, less than 20% had a BMI > 40 kg/m2. Blood pressure was generally within normal limits for all groups as required by the protocol, with nearly 70% of the subjects taking anti-hypertensive medication. Fasting glucose was similar for all gender ethnic groups averaging over 150 mg/dl, except African-American and Asian-American men and women in whom it was between 7.9 and 8.3 mmol/l. About one quarter of men and women (20.2 to 27.6%) had an HbA1c < 6.5%. Only a small number (8% overall) had HbA1c values that were > 9%. Total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol were higher in the women than the men, but triglycerides were lower. Triglycerides were considerably lower in African-Americans and Asian American women than in other groups. American Indians had, on average, lower lipid values than other ethnic groups; however, they were also younger. Among the men, 38.2% to 59.1% across the different ethnic groups were taking lipid lowering medications, which was higher than the 25.5% to 49.3% among the women.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics in male subjects by race/ethnicity

| Variable | All | Caucasian | African American | Hispanic | American Indian | Asian American | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 2081 | 1581 | 190 | 196 | 55 | 16 | 41 |

| Age (yrs) | |||||||

| 524 (25.2%) | 371 (23.5%) | 57 (30.0%) | 58 (29.6%) | 24 (43.6%) | 4 (25.0%) | 9 (22.0%) | |

| 1115 (53.6%) | 859 (54.3%) | 92 (48.4%) | 109 (55.6%) | 22 (40.0%) | 9 (56.3%) | 23 (56.1%) | |

| 442 (21.2%) | 351 (22.2%) | 41 (21.6%) | 29 (14.8%) | 9 (16.4%) | 3 (18.8%) | 9 (22.0%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| 25 – 27 | 46 (2.2%) | 32 (2.0%) | 5 (2.6%) | 3 (1.5%) | 3 (5.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (2.4%) |

| 27 – 30 | 294 (14.1%) | 216 (13.7%) | 23 (12.1%) | 29 (14.8%) | 11 (20.0%) | 9 (56.3%) | 6 (14.6%) |

| 30 – 35 | 833 (40.0%) | 623 (39.4%) | 72 (37.9%) | 92 (46.9%) | 26 (47.3%) | 4 (25.0%) | 15 (36.6%) |

| 35 – 40 | 535 (25.7%) | 417 (26.4%) | 51 (26.8%) | 41 (20.9%) | 9 (16.4%) | 1 (6.3%) | 16 (39.0%) |

| >= 40 | 372 (17.9%) | 292 (18.5%) | 39 (20.5%) | 31 (15.8%) | 6 (10.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (7.3%) |

| Blood Pressure (mmHg) | |||||||

| Systolic | 128.52 ± 16.57 | 128.70 ± 16.78 | 128.72 ± 15.81 | 128.37 ± 15.51 | 124.51 ± 14.40 | 123.97 ± 19.03 | 128.24 ± 18.59 |

| Diastolic | 73.21 ± 9.17 | 72.65 ± 9.02 | 75.49 ± 9.52 | 74.25 ± 9.09 | 76.17 ± 7.96 | 75.43 ± 12.76 | 74.36 ± 11.15 |

| Antihypertensive medication, n (%) | 1450 (69.7%) | 1121 (70.9%) | 136 (71.6%) | 127 (64.8%) | 30 (54.5%) | 8 (50.0%) | 27 (65.9%) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 156.07 ± 46.12 | 157.70 ± 45.65 | 146.89 ± 49.91 | 156.70 ± 46.13 | 150.28 ± 46.33 | 140.60 ± 42.37 | 147.21 ± 42.61 |

| HbA1c (%) | |||||||

| < 6.0 | 170 (8.4%) | 129 (8.4%) | 13 (7.0%) | 19 (9.8%) | 5 (10.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (5.1%) |

| 6.0 – 6.5 | 344 (17.0%) | 265 (17.3%) | 27 (14.4%) | 30 (15.5%) | 7 (14.0%) | 3 (20.0%) | 11 (28.2%) |

| 6.5 – 7.0 | 410 (20.3%) | 337 (22.0%) | 29 (15.5%) | 25 (13.0%) | 7 (14.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 8 (20.5%) |

| 7.0 – 8.0 | 619 (30.6%) | 468 (30.5%) | 56 (29.9%) | 64 (33.2%) | 16 (32.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 11 (28.2%) |

| 8.0 – 9.0 | 317 (15.7%) | 233 (15.2%) | 38 (20.3%) | 33 (17.1%) | 8 (16.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 4 (10.3%) |

| > 9.0 | 161 (8.0%) | 103 (6.7%) | 24 (12.8%) | 22 (11.4%) | 7 (14.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| Plasma lipids (mg/dl) | |||||||

| Total cholesterol | 182.20 ± 36.22 | 182.02 ± 36.23 | 185.14 ± 37.83 | 185.90 ± 36.58 | 170.30 ± 34.50 | 176.87 ± 27.86 | 175.13 ± 27.87 |

| HDL cholesterol | 38.05 ± 9.09 | 37.64 ± 8.79 | 42.22 ± 10.62 | 37.09 ± 8.57 | 36.50 ± 8.85 | 42.80 ± 11.94 | 39.79 ± 8.68 |

| LDL cholesterol | 107.07 ± 30.61 | 106.12 ± 30.12 | 115.45 ± 32.46 | 109.37 ± 33.45 | 98.66 ± 29.58 | 98.00 ± 19.35 | 107.13 ± 23.98 |

| Triglycerides | 192.01 ± 129.75 | 198.20 ± 129.64 | 141.98 ± 121.38 | 203.92 ± 138.28 | 181.20 ± 99.60 | 200.67 ± 184.31 | 142.54 ± 70.65 |

| Lipid-lowering medication, n (%) | 1148 (55.2%) | 935 (59.1%) | 84 (44.2%) | 79 (40.3%) | 21 (38.2%) | 8 (50.0%) | 20 (48.8%) |

| CVD History, n (%) | 442 (21.2%) | 362 (22.9%) | 26 (13.7%) | 29 (14.8%) | 10 (18.2%) | 4 (25.0%) | 11 (26.8%) |

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics in female subjects by race/ethnicity.

| Variable | All | Caucasian | African American | Hispanic | American Indian | Asian American | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 3054 | 1664 | 614 | 480 | 204 | 34 | 57 |

| Age (yrs) | |||||||

| 1091 (35.7%) | 530 (31.9%) | 226 (36.8%) | 182 (37.9%) | 116 (56.9%) | 14 (41.2%) | 23 (40.4%) | |

| 1533 (50.2%) | 850 (51.1%) | 312 (50.8%) | 262 (54.6%) | 66 (32.4%) | 15 (44.1%) | 27 (47.4%) | |

| 429 (14.1%) | 283 (17.0%) | 76 (12.4%) | 36 (7.5%) | 22 (10.8%) | 5 (14.7%) | 7 (12.3%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| 25 – 27 | 71 (2.3%) | 39 (2.3%) | 13 (2.1%) | 5 (1.0%) | 8 (3.9%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 27 – 30 | 354 (11.6%) | 183 (11.0%) | 62 (10.1%) | 74 (15.4%) | 21 (10.3%) | 9 (26.5%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| 30 – 35 | 977 (32.0%) | 518 (31.1%) | 186 (30.3%) | 181 (37.7%) | 65 (32.0%) | 13 (38.2%) | 14 (24.6%) |

| 35 – 40 | 874 (28.6%) | 477 (28.7%) | 188 (30.7%) | 129 (26.9%) | 54 (26.6%) | 4 (11.8%) | 22 (38.6%) |

| >= 40 | 776 (25.4%) | 447 (26.9%) | 164 (26.8%) | 91 (19.0%) | 55 (27.1%) | 3 (8.8%) | 16 (28.1%) |

| Blood Pressure (mmHg) | |||||||

| Systolic | 129.02 ± 17.59 | 128.97 ± 17.71 | 131.55 ± 17.51 | 127.60 ± 16.53 | 123.47 ± 16.91 | 127.26 ± 18.24 | 134.88 ± 19.39 |

| Diastolic | 68.08 ± 9.38 | 67.14 ± 8.93 | 71.53 ± 9.42 | 66.93 ± 9.11 | 66.62 ± 10.67 | 69.91 ± 10.36 | 71.68 ± 9.03 |

| Antihypertensive medication, n (%) | 2068 (67.7%) | 1138 (68.4%) | 478 (77.9%) | 302 (62.9%) | 87 (42.6%) | 23 (67.6%) | 39 (68.4%) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 151.06 ± 45.19 | 152.70 ± 44.00 | 143.62 ± 46.47 | 156.05 ± 46.91 | 150.12 ± 46.95 | 143.18 ± 50.94 | 147.40 ± 31.52 |

| HbA1c (%) | |||||||

| < 6.0 | 201 (6.6%) | 139 (8.4%) | 24 (3.9%) | 19 (4.0%) | 13 (6.4%) | 1 (2.9%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| 6.0 – 6.5 | 560 (18.3%) | 322 (19.4%) | 109 (17.8%) | 77 (16.0%) | 35 (17.2%) | 8 (23.5%) | 9 (15.8%) |

| 6.5 – 7.0 | 629 (20.6%) | 373 (22.4%) | 114 (18.6%) | 89 (18.5%) | 38 (18.6%) | 4 (11.8%) | 11 (19.3%) |

| 7.0 – 8.0 | 942 (30.8%) | 517 (31.1%) | 192 (31.3%) | 144 (30.0%) | 57 (27.9%) | 12 (35.3%) | 19 (33.3%) |

| 8.0 – 9.0 | 464 (15.2%) | 209 (12.6%) | 112 (18.2%) | 91 (19.0%) | 35 (17.2%) | 7 (20.6%) | 10 (17.5%) |

| > 9.0 | 258 (8.4%) | 104 (6.3%) | 63 (10.3%) | 60 (12.5%) | 26 (12.7%) | 2 (5.9%) | 3 (5.3%) |

| Lipids (mg/dl) | |||||||

| Total cholesterol | 196.97 ± 37.36 | 198.00 ± 37.32 | 195.53 ± 36.10 | 198.11 ± 36.49 | 186.65 ± 40.29 | 199.61 ± 43.35 | 204.46 ± 40.64 |

| HDL cholesterol | 47.19 ± 12.05 | 46.25 ± 11.08 | 52.20 ± 14.74 | 44.96 ± 10.79 | 44.46 ± 9.75 | 48.55 ± 9.34 | 49.23 ± 11.13 |

| LDL cholesterol | 115.83 ± 32.86 | 115.16 ± 32.41 | 119.89 ± 33.34 | 115.94 ± 32.36 | 105.13 ± 32.64 | 120.09 ± 35.78 | 124.02 ± 35.76 |

| Triglycerides | 174.65 ± 109.02 | 188.80 ± 106.66 | 119.56 ± 68.10 | 191.29 ± 115.43 | 192.49 ± 157.07 | 151.18 ± 60.85 | 162.28 ± 100.33 |

| Lipid-lowering medication, n (%) | 1292 (42.3%) | 820 (49.3%) | 212 (34.5%) | 176 (36.7%) | 52 (25.5%) | 12 (35.3%) | 20 (35.1%) |

| CVD History, n (%) | 283 (9.3%) | 160 (9.6%) | 55 (9.0%) | 38 (7.9%) | 17 (8.3%) | 6 (17.6%) | 7 (12.3%) |

| Prior Pregnancy, n (%) | 2695 (88.2%) | 1424 (85.6%) | 566 (92.2%) | 435 (90.6%) | 190 (93.1%) | 25 (73.5%) | 54 (94.7%) |

Over 90% of this sample had the metabolic syndrome as defined by the NCEP Adult Treatment Panel III criteria (11). A high waist circumference, prevalence of hypertension >80%, and diabetes (present in all participants) were responsible for the high prevalence of this syndrome. Triglycerides > 150 mg/dL were observed in only 48% of the participants. A low HDL-cholesterol was present in 66% (not shown).

Overall, 14% of the participants reported a history of CVD. CVD was more common in the men (21.2%) than the women (9.3%). 6.1% reported having a previous myocardial infarction with men being 3 times as likely as women (10.3% vs 3.2%) (not shown). Just over 2% of the population reported a history of a cerebrovascular accident (stroke) at baseline with an equal distribution between the sexes. However, a history of coronary artery bypass grafting and/or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty was again more than 3 times as high in the men as in the women.

Medication Use

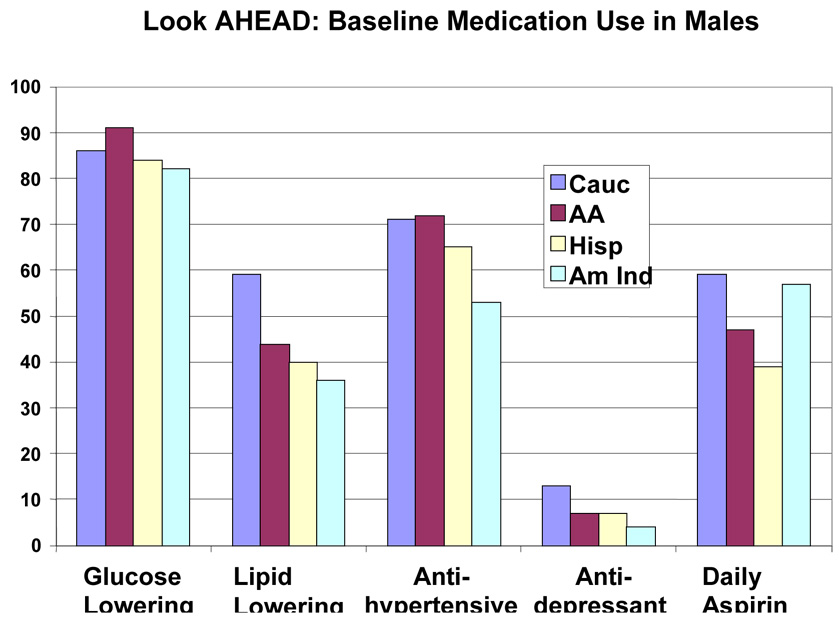

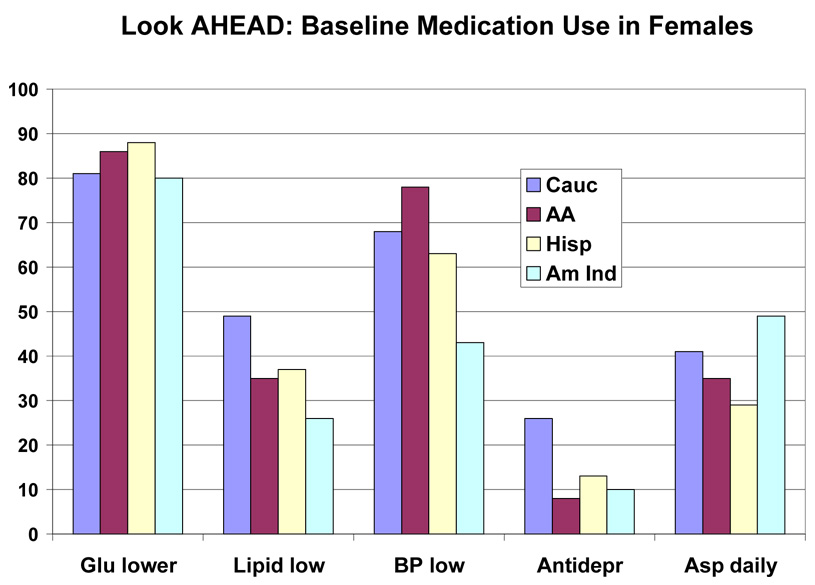

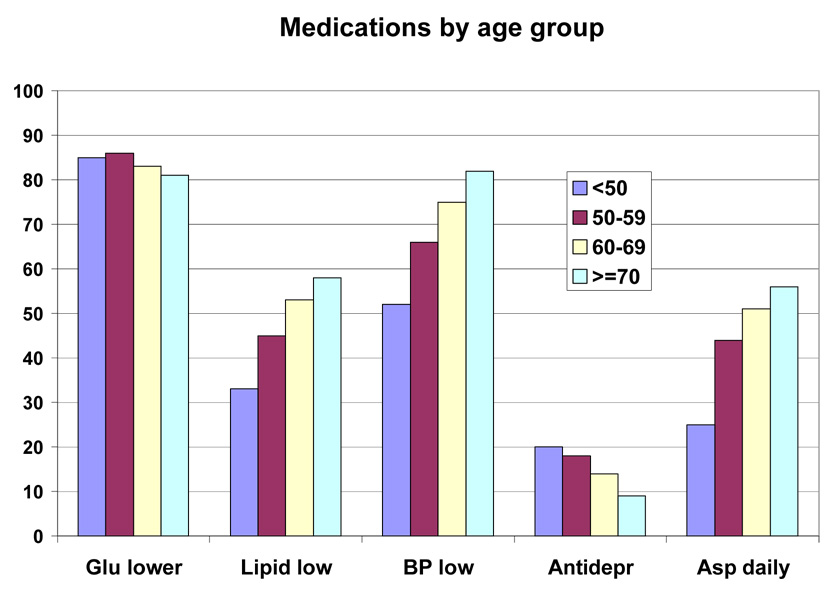

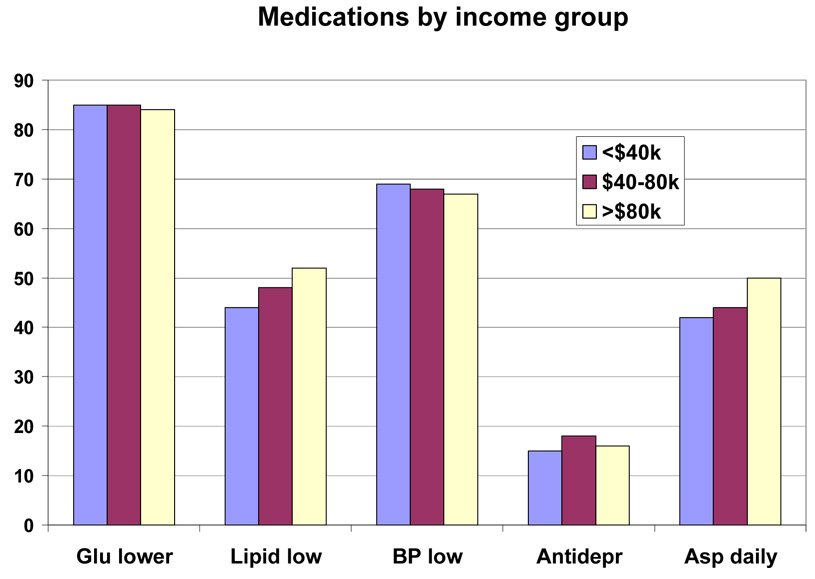

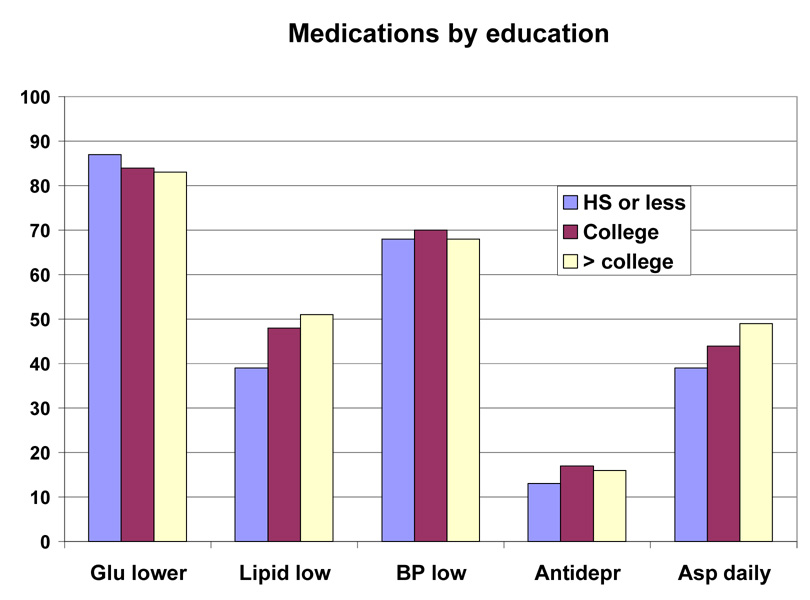

Baseline medications by race/ethnic group are shown in Table 5 and by race/ethnic group and sex in Figure 2 and Figure 3. This was a medicated population with a high frequency of medication use. More than 80% were taking one or more glucose-lowering medicines, and just under half of the group were taking two or more glucose-lowering medicines (36.3% to 48.0%). Metformin was the most frequently (48.3% to 62.0%) used drugs, and it was used similarly by people of all education levels (Table 7), but was used less frequently in those with the lowest income (Table 8), and in those over 70 years of age (39.4% vs > 50% for younger age groups) (Table 6). Sulfonylureas were used only slightly less frequently (38.4% to 52.0%); they were used less frequently among those with more education and higher income (Table 7–Table 8). Thiazolidinediones were used by a smaller number (7.3 to 27.4%) and insulin by an even small number (13.2% to 17.8%). For each of these drugs there was a gradient across education/income levels. Insulin was used a third less often in the upper income/education group and thiazolidinediones 50% more. There was no difference by age (Table 6).

Table 5.

Baseline medication inventory by race/ethnicity

| Variable | All | Caucasian | African American | Hispanic | American Indian | Asian American | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Lowering | 4305 (83.8%) | 2690 (82.9%) | 696 (86.6%) | 584 (86.4%) | 209 (80.7%) | 44 (88.0%) | 0.9363 |

| Insulin | 750 (14.6%) | 429 (13.2%) | 143 (17.8%) | 112 (16.6%) | 44 (17.0%) | 8 (16.0%) | 0.4016 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 1257 (24.5%) | 888 (27.4%) | 208 (25.9%) | 107 (15.8%) | 19 (7.3%) | 10 (20.0%) | 0.0047 |

| Sulfonylurea | 2288 (44.6%) | 1407 (43.4%) | 361 (44.9%) | 336 (49.7%) | 118 (45.6%) | 26 (52.0%) | 0.5731 |

| Metformin | 2685 (52.3%) | 1726 (53.2%) | 388 (48.3%) | 353 (52.2%) | 138 (53.3%) | 31 (62.0%) | 0.3376 |

| More than one glucose lowering medication | 2133 (41.5%) | 1364 (42.0%) | 345 (42.9%) | 268 (39.6%) | 94 (36.3%) | 24 (48.0%) | 0.1402 |

| Lipid Lowering | 2442 (47.6%) | 1756 (54.1%) | 297 (36.9%) | 255 (37.7%) | 72 (27.8%) | 20 (40.0%) | 0.6219 |

| Statin | 2226 (43.3%) | 1592 (49.1%) | 290 (36.1%) | 219 (32.4%) | 69 (26.6%) | 18 (36.0%) | 0.3194 |

| Fibrate | 332 (6.5%) | 260 (8.0%) | 12 (1.5%) | 46 (6.8%) | 7 (2.7%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.0006 |

| Niacin | 63 (1.2%) | 55 (1.7%) | 2 (0.2%) | 5 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.7851 |

| Antihypertensive | 3510 (68.4%) | 2259 (69.6%) | 610 (75.9%) | 429 (63.5%) | 115 (44.4%) | 29 (58.0%) | 0.0005 |

| ACE Inhibitors | 1617 (31.5%) | 1044 (32.2%) | 258 (32.1%) | 234 (34.6%) | 35 (13.5%) | 12 (24.0%) | 0.0264 |

| Angiotensin Receptor Blockers | 580 (11.3%) | 365 (11.3%) | 103 (12.8%) | 63 (9.3%) | 25 (9.7%) | 12 (24.0%) | 0.2386 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 793 (15.4%) | 475 (14.6%) | 193 (24.0%) | 68 (10.1%) | 27 (10.4%) | 8 (16.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Beta Blockers | 955 (18.6%) | 656 (20.2%) | 162 (20.1%) | 91 (13.5%) | 19 (7.3%) | 10 (20.0%) | 0.0022 |

| Diuretics | 1465 (28.5%) | 926 (28.5%) | 312 (38.8%) | 134 (19.8%) | 48 (18.5%) | 9 (18.0%) | <0.0001 |

| More than one Antihypertensive | 1543 (30.0%) | 994 (30.6%) | 316 (39.3%) | 138 (20.4%) | 38 (14.7%) | 15 (30.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Antidepressants | 821 (16.0%) | 639 (19.7%) | 63 (7.8%) | 74 (10.9%) | 22 (8.5%) | 5 (10.0%) | 0.0920 |

| Aspirin | 0.1388 | ||||||

| Never | 2272 (45.1%) | 1296 (40.8%) | 424 (53.5%) | 377 (56.0%) | 107 (43.0%) | 27 (55.1%) | - |

| Sometimes | 487 (9.7%) | 305 (9.6%) | 71 (9.0%) | 81 (12.0%) | 17 (6.8%) | 1 (2.0%) | - |

| Every Day | 2283 (45.3%) | 1575 (49.6%) | 298 (37.6%) | 215 (31.9%) | 125 (50.2%) | 21 (42.9%) | - |

“Other” race not presented separately here due to small sample size (n=80); however, other is included in “All” column.

adjusted for age, sex, and education.

Figure 2.

Baseline Medication Use in Males in the Look AHEAD study. Data are expressed as percent of each male ethnic group for each medication

Figure 3.

Baseline Medication Use in Females in the Look AHEAD Study. Data are expressed as percent of each femaleethnic group for each medication

Table 7.

Baseline medication inventory by education group.

| Variable | All | < 13 yr | 13–16 yr | > 16 yr | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Lowering | 4244 (84.4%) | 892 (87.1%) | 1613 (84.4%) | 1739 (83.1%) | 0.0001 |

| Insulin | 736 (14.6%) | 171 (16.7%) | 278 (14.5%) | 287 (13.7%) | 0.0225 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 1233 (24.5%) | 190 (18.6%) | 491 (25.7%) | 552 (26.4%) | 0.0039 |

| Sulfonylurea | 2255 (44.8%) | 512 (50.0%) | 857 (44.8%) | 886 (42.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Metformin | 2629 (52.3%) | 530 (51.8%) | 986 (51.6%) | 1113 (53.2%) | 0.4514 |

| More than one glucose lowering med | 2101 (41.8%) | 425 (41.5%) | 796 (41.7%) | 880 (42.0%) | 0.2608 |

| Lipid Lowering | 2380 (47.3%) | 400 (39.1%) | 920 (48.1%) | 1060 (50.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Statin | 2165 (43.1%) | 349 (34.1%) | 843 (44.1%) | 973 (46.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Fibrate | 324 (6.4%) | 56 (5.5%) | 125 (6.5%) | 143 (6.8%) | 0.8216 |

| Niacin | 62 (1.2%) | 13 (1.3%) | 16 (0.8%) | 33 (1.6%) | 0.7168 |

| Antihypertensive | 3449 (68.6%) | 693 (67.7%) | 1336 (69.9%) | 1420 (67.8%) | 0.3627 |

| ACE Inhibitors | 1578 (31.4%) | 332 (32.4%) | 596 (31.2%) | 650 (31.1%) | 0.3574 |

| Angiotensin Receptor Blockers | 563 (11.2%) | 90 (8.8%) | 215 (11.3%) | 258 (12.3%) | 0.0009 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 775 (15.4%) | 150 (14.6%) | 311 (16.3%) | 314 (15.0%) | 0.4655 |

| Beta Blockers | 939 (18.7%) | 186 (18.2%) | 387 (20.3%) | 366 (17.5%) | 0.0260 |

| Diuretics | 1430 (28.4%) | 308 (30.1%) | 578 (30.2%) | 544 (26.0%) | 0.0219 |

| More than one Antihypertensive | 1503 (29.9%) | 296 (28.9%) | 604 (31.6%) | 603 (28.8%) | 0.3411 |

| Antidepressants | 795 (15.8%) | 130 (12.7%) | 331 (17.3%) | 334 (16.0%) | 0.0012 |

| Aspirin | 0.0019 | ||||

| Never | 2231 (45.2%) | 512 (50.9%) | 878 (46.8%) | 841 (40.9%) | - |

| Sometimes | 477 (9.7%) | 104 (10.3%) | 170 (9.1%) | 203 (9.9%) | - |

| Every Day | 2231 (45.2%) | 390 (38.8%) | 830 (44.2%) | 1011 (49.2%) | - |

adjusted for race, sex, and age

Table 8.

Baseline medication inventory by income group.

| Variable | All | < $40k | $40k – $80k | > $80k | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Lowering | 3929 (84.7%) | 1341 (85.3%) | 1448 (85.0%) | 1140 (83.9%) | 0.0035 |

| Insulin | 687 (14.8%) | 280 (17.8%) | 238 (14.0%) | 169 (12.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 1144 (24.7%) | 300 (19.1%) | 456 (26.8%) | 388 (28.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Sulfonylurea | 2074 (44.7%) | 730 (46.4%) | 760 (44.6%) | 584 (43.0%) | 0.0006 |

| Metformin | 2457 (53.0%) | 772 (49.1%) | 931 (54.6%) | 754 (55.5%) | 0.0101 |

| More than one glucose lowering med | 1955 (42.2%) | 617 (39.2%) | 755 (44.3%) | 583 (42.9%) | 0.9074 |

| Lipid Lowering | 2222 (47.9%) | 685 (43.5%) | 825 (48.4%) | 712 (52.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Statin | 2021 (43.6%) | 637 (40.5%) | 742 (43.5%) | 642 (47.2%) | 0.0005 |

| Fibrate | 308 (6.6%) | 64 (4.1%) | 131 (7.7%) | 113 (8.3%) | 0.0015 |

| Niacin | 57 (1.2%) | 16 (1.0%) | 22 (1.3%) | 19 (1.4%) | 0.5346 |

| Antihypertensive | 3154 (68.0%) | 1090 (69.3%) | 1160 (68.1%) | 904 (66.5%) | 0.5140 |

| ACE Inhibitors | 1474 (31.8%) | 484 (30.8%) | 544 (31.9%) | 446 (32.8%) | 0.5047 |

| Angiotensin Receptor Blockers | 510 (11.0%) | 165 (10.5%) | 199 (11.7%) | 146 (10.7%) | 0.1204 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 710 (15.3%) | 258 (16.4%) | 259 (15.2%) | 193 (14.2%) | 0.2895 |

| Beta Blockers | 848 (18.3%) | 306 (19.5%) | 313 (18.4%) | 229 (16.9%) | 0.0977 |

| Diuretics | 1299 (28.0%) | 494 (31.4%) | 476 (27.9%) | 329 (24.2%) | 0.0736 |

| More than one Antihypertensive | 1369 (29.5%) | 492 (31.3%) | 498 (29.2%) | 379 (27.9%) | 0.5801 |

| Antidepressants | 751 (16.2%) | 237 (15.1%) | 298 (17.5%) | 216 (15.9%) | 0.0438 |

| Aspirin | 0.0008 | ||||

| Never | 2061 (45.2%) | 759 (49.0%) | 768 (45.9%) | 534 (40.0%) | - |

| Sometimes | 441 (9.7%) | 135 (8.7%) | 171 (10.2%) | 135 (10.1%) | - |

| Every Day | 2056 (45.1%) | 655 (42.3%) | 736 (43.9%) | 665 (49.9%) | - |

adjusted for race, sex, and age

Table 6.

Baseline medication inventory by age group.

| Variable | All | < 50 yr | 50–59 yr | 60–69 yr | >= 70 yr | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Lowering | 4339 (84.3%) | 470 (85.0%) | 2035 (85.6%) | 1541 (83.2%) | 293 (80.7%) | 0.0003 |

| Insulin | 750 (14.6%) | 79 (14.3%) | 342 (14.4%) | 275 (14.8%) | 54 (14.9%) | 0.6576 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 1259 (24.5%) | 121 (21.9%) | 624 (26.3%) | 440 (23.8%) | 74 (20.4%) | 0.0249 |

| Sulfonylurea | 2295 (44.6%) | 235 (42.5%) | 1053 (44.3%) | 844 (45.6%) | 163 (44.9%) | 0.8570 |

| Metformin | 2688 (52.2%) | 305 (55.2%) | 1284 (54.0%) | 956 (51.6%) | 143 (39.4%) | <0.0001 |

| More than one glucose lowering med | 2137 (41.5%) | 223 (40.3%) | 1002 (42.2%) | 789 (42.6%) | 123 (33.9%) | 0.0159 |

| Lipid Lowering | 2441 (47.4%) | 183 (33.1%) | 1073 (45.1%) | 974 (52.6%) | 211 (58.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Statin | 2221 (43.2%) | 166 (30.0%) | 976 (41.1%) | 885 (47.8%) | 194 (53.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Fibrate | 333 (6.5%) | 24 (4.3%) | 155 (6.5%) | 137 (7.4%) | 17 (4.7%) | 0.5218 |

| Niacin | 63 (1.2%) | 3 (0.5%) | 24 (1.0%) | 26 (1.4%) | 10 (2.8%) | 0.0119 |

| Antihypertensive | 3530 (68.6%) | 288 (52.1%) | 1565 (65.8%) | 1379 (74.5%) | 298 (82.1%) | <0.0001 |

| ACE Inhibitors | 1620 (31.5%) | 154 (27.8%) | 735 (30.9%) | 613 (33.1%) | 118 (32.5%) | 0.6289 |

| Angiotensin Receptor Blockers | 578 (11.2%) | 39 (7.1%) | 264 (11.1%) | 217 (11.7%) | 58 (16.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 792 (15.4%) | 55 (9.9%) | 325 (13.7%) | 341 (18.4%) | 71 (19.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Beta Blockers | 957 (18.6%) | 56 (10.1%) | 374 (15.7%) | 432 (23.3%) | 95 (26.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Diuretics | 1467 (28.5%) | 104 (18.8%) | 639 (26.9%) | 598 (32.3%) | 126 (34.7%) | <0.0001 |

| More than one Antihypertensive | 1543 (30.0%) | 106 (19.2%) | 637 (26.8%) | 654 (35.3%) | 146 (40.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Antidepressants | 821 (16.0%) | 109 (19.7%) | 426 (17.9%) | 253 (13.7%) | 33 (9.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Aspirin | <0.0001 | |||||

| Never | 2275 (45.0%) | 347 (63.3%) | 1100 (47.0%) | 705 (38.9%) | 123 (35.0%) | - |

| Sometimes | 487 (9.6%) | 63 (11.5%) | 216 (9.2%) | 178 (9.8%) | 30 (8.5%) | - |

| Every Day | 2290 (45.3%) | 138 (25.2%) | 1023 (43.7%) | 931 (51.3%) | 198 (56.4%) | - |

adjusted for race, sex, and education.

Lipid lowering drugs were used by 27.8% to 54.1% of the participants. Statins were the most common drug used in this class. There was greater use of this class of drugs in those subgroups with more education, more income and older age. Antihypertensive drugs were used by 44.4% to 75.9% (Table 5). Among this group of drugs, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) were used less than diuretics (range for ACEi 13.5 to 34.6% vs range for diuretics 18.0 to 38.8%). Calcium channel blockers (CCB) were used less than beta-blockers (10.1 to 24.0% vs 7.3 to 20.2%). Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) were the least frequently used anti-hypertensive drug (9.3 to 24.0%) (Table 5). The use of CCBs and ARBs (but not ACEi) was positively associated with age. However, among these three antihypertensive drugs, there was no gradient by income or educational level (except for ARBs, the use of which was associated with education). Anti-depressants were used by 16.0% of the participants. Use was higher in younger participants (19.7%) and lowest in those over age 70 (9.1%) (Table 6). Aspirin was used daily by 31.9 to 50.2% of the population and on some days by 2.0 to 12.1%, meaning that a significant number of diabetic participants in this trial were not taking aspirin (45% overall). There was a higher use of aspirin in those with more education, higher income, and greater age (Table 6–Table 8 or Figure 4–Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Baseline Medication Use by Age Groups in the Look AHEAD Study. Data are expressed as percent of each age group.

Figure 6.

Baseline Medication Use by Income Group in the Look AHEAD study. Data are expressed as percent of each income group.

The Look AHEAD Population Compared to the NHANES III and NHANES 1999–2002 sample of Persons with Diabetes

To compare the Look AHEAD participants with the general U.S. population, we examined the characteristics of the NHANES III and NHANES 1999–2000 participants —a representative sample of the U.S. population (Table 9). These NHANES samples had self-reported diabetes and were also defined by the same age and BMI criteria as required for participation in Look AHEAD. The Look AHEAD participants are younger, with only 17% aged 65–76 years, compared to more than 30% in the two NHANES sample of persons with diabetes. The proportion of women was modestly higher in Look AHEAD (59.4% vs approximately 50%). The difference in the proportion of racial/ethnic minorities with diabetes between the two NHANES evaluations is evident, with proportionally more Hispanics and fewer Whites in the later survey. The Look AHEAD participants had a similar ethnic distribution to that of NHANES 1999–2000. BMI was significantly higher in the Look AHEAD participants as required by the protocol for enrollment. Significant trends for improvement in education were evident between NHANES III and NHANES 1999–2000 (4). Look AHEAD participants were better educated (80.1% > 12 years of education vs 34.9% for the NHANES 1999–2000 sample). Participants in Look AHEAD were less likely to smoke than the general population of persons with diabetes (4.4% vs 16.2%) suggesting that there was a self-selection bias among volunteers for Look AHEAD. Significant temporal trends for improvement in lipid levels in the general population from NHANES surveys (4) and in these two diabetic subgroups is evident for all classes of lipids. Lipid levels were somewhat better in the Look AHEAD participants compared to NHANES III, but were similar to those in NHANES 1999–2000. Fasting plasma glucose concentrations and HbA1c both improved between NHANES III and NHANES 1999–2000, but glucose and HbA1c values were even lower in Look AHEAD than in the representative sample from NHANES of persons with diabetes suggesting that the severity of the diabetes, or the quality of control differed. In summary, with the exception of obesity, the Look AHEAD cohort is healthier, and consequently, at less risk for CVD than the general population of persons with diabetes in the US.

Table 9.

Comparison of Look AHEAD participants with NHANES participants.

| Variable | Look AHEAD | NHANES III | NHANES 1999–2000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 5145 | 695 | 481 |

| Age (yrs) | |||

| 45 – 55 (%) | 31.5 | 23.1 (2.7) | 30.7 (2.6) |

| 55 – 65 (%) | 51.5 | 41.7 (3.3) | 34.8 (2.2) |

| 65 – 76 (%) | 17.0 | 35.3 (2.9) | 34.6 (2.6) |

| Female (%) | 59.4 | 52.4 (3.2) | 48.3 (2.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| African American/Black | 15.6 | 15.9 (1.6) | 16.8 (3.0) |

| American Indian | 5.1 | n/a | n/a |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.0 | n/a | n/a |

| White | 63.3 | 73.1 (2.4) | 63.3 (3.8) |

| Hispanic | 13.2 | 6.0 (0.6) | 16.1 (4.0) |

| Other | 1.9 | 5.1 (1.7) | 3.8 (1.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.94 | 32.2 (0.3) | 33.9 (0.4) |

| Education (years) | |||

| < 12 years | 6.7 | 46.7 (3.1) | 38.1 (2.9) |

| 12 years | 13.2 | 31.3 (2.9) | 27.0 (2.2) |

| > 12 years | 80.1 | 22.0 (3.1) | 34.9 (3.0) |

| Smoking Status (%) | |||

| Never | 50.2 | 38.8 (2.7) | 45.6 (4.2) |

| Past | 45.4 | 49.2 (3.3) | 38.2 (2.9) |

| Present | 4.4 | 12.0 (2.3) | 16.2 (2.0) |

| Hypertension (%) | 80.3 | 61.5 (2.7) | 70.0 (3.4) |

| Lipids (mean, SE) | |||

| Total cholesterol | 190.99 | 228.9 (2.5) | 205.0 (2.6) |

| LDL Cholesterol | 112.29 | 140.4 (3.0) | 116.0 (3.5) |

| HDL Cholesterol | 43.47 | 43.6 (1.6) | 45.9 (1.3) |

| Triglycerides | 180.95 | 255.5 (34.1) | 181.5 (11.1) |

| Fasting glucose (mean, SE) | 153.12 | 190.5 (6.5) | 154.7 (5.38) |

| Hemoglobin A1c% (mean, SE) | 7.28 | 7.74 (0.11) | 7.56 (0.10) |

| Lipid-lowering medication (%) | 47.6 | 14.3 (2.4) | 38.6 (2.6) |

| Antihypertensive medication (%) | 68.4 | 47.3 (2.8) | 61.0 (3.4) |

| Insulin (%) | 14.6 | 24.6 (1.9) | 14.8 (2.7) |

NHANES samples restricted to those with BMI > 25 kg/m2, age 45–74 years, with self-reported diabetes. Standard errors are reported for NHANES samples from weighted analyses. Fasting blood measures are based on a reduced sample (n=316 for NHANES III, and n=154 for NHANES 1999–2002).

Discussion

The primary outcome of the Look AHEAD trial is the development of cardiovascular disease or death. Secondary outcomes include components of cardiovascular disease risk, cost and cost-effectiveness, diabetes control and complications, hospitalizations, intervention processes and the quality of life. The Look AHEAD trial was designed with an intention-to-treat analysis plan (2). The final sample size (5145 participants) will provide >90% power to detect an 18% reduction in the rate of primary outcomes among participants assigned to the lifestyle intervention with a 5% level of significance (two-sided), after adjustment for losses to follow-up (2). This assumes a rate of 3.125% per year in the development of primary outcomes in those assigned to the Diabetes Support and Education Control group. Participants were randomized over a 2.5 year period and are to be followed for up to 11.5 years. To protect participant welfare, interim results are reviewed by a data and safety monitoring board (2). The study is scheduled to complete participant follow-up in June 2012.

Our predetermined target was to include >33% of participants from U.S. minority ethnic and racial groups, and 37% of the Look AHEAD cohort met those criteria. The remaining 63%, self-identified as White, likely represent a varied pool of individuals with ancestry from Europe as well as western Asia and the Middle East. The heterogeneity of the U.S. minority subgroups should also be noted, because the African-American designation included people of Afro-Caribbean descent, and the term “Hispanic” includes individuals from Latin America and the Caribbean without regard to racial admixture. American Indian participants in Look AHEAD are concentrated in the Southwest because three centers recruited exclusively from regional tribes; small numbers of American Indian participants were randomized in other centers. Asian-Americans in Look AHEAD included participants descended from Japanese, Chinese, other East Asian groups, Asian Indians, and Pacific Rim Australasian populations.

As the study is aimed at determining whether CVD events can be reduced by a lifestyle intervention in persons with diabetes, it is not surprising that risk factors for CHD were highly prevalent in the Look AHEAD cohort. Fourteen percent had a history of CVD which was higher for men than women. A history of and/or treatment for hypertension was present in 80% of individuals. Dyslipidemia was present in a large proportion of participants. More than 55% of men and 42% of women reported a history of and/or treatment for high cholesterol. When comparing the two representative samples of persons with diabetes from the general population in NHANES III and NHANES 1999-2000 and the Look AHEAD samples two conclusions are obvious. First, lipid values have improved in the samples from persons with diabetes just as they have in the temporal data from NHANES samples for the broader population (5). Second, even though the Look AHEAD cohort is more obese with a higher BMI, lipid profiles are more favorable than the NHANES samples from persons with diabetes. Based on baseline characteristics, 93% of the cohort is classified has having the metabolic syndrome using the criteria proposed by the National Cholesterol Education Program ATPIII panel (11).

Look AHEAD selected participants who were overweight, (BMI ≥25 kg/m2). Its cohort has many obese individuals. BMI was ≥40 kg/m2 in 18% of men and 25% of women. This far exceeds the general population where only 5% of men and 14% of women have a BMI > 40 kg/m2 (12).

Diabetes is considered a “cardiovascular risk equivalent” (13) because the rate of first myocardial infarction and stroke is as high as age and sex matched people who have already had their first myocardial infarction. Among the recommendations for persons with diabetes is the use of low-dose aspirin (14), yet in the Look AHEAD study population nearly 50% of most ethnic groups reported never using aspirin. Over 80% of each ethnic group were taking anti-diabetic drugs, and approximately 40% were taking more than one. The most common anti-diabetic drug was metformin with sulfonylureas used almost as frequently. In Whites and African-Americans insulin was used half as much as thiazolidinediones, whereas in the other groups they were used equally or insulin was used more often (American Indians). Use of antihypertensives was common with 15 to 42% taking more than one drug in this class. Lipid lowering agents were used by nearly 50% with statins being the predominant drug category. Finally, depression is more common in persons with diabetes than in the general population (15, 16) and this may account for the 8 to 20% who were taking anti-depressant drugs. However, this is considerably higher than the 5.7% reported for the baseline population in the Diabetes Prevention Program (17). Clearly the Look AHEAD population is a medicated sample is a population with a high frequency of medication use at baseline.

In conclusion, the data obtained at baseline in the participants randomized to participate in the Look AHEAD Research Study indicate that the study has recruited a cohort comprising individuals of a broad age range who are representative of groups in the United States. By virtue of the fact that the cohort has a variety of metabolic characteristics associated with type 2 diabetes and CVD, including obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, it appears appropriate to test the primary study question as to whether a lifestyle intervention is able to reduce CVD events in individuals with type 2 diabetes. These participants represent a cohort comprising older individuals as well as subjects from U.S. minority racial/ethnic groups who have a high prevalence type 2 diabetes. The participants have a variety of metabolic risk factors associated with type 2 diabetes and CVD, which put them at risk for cardiovascular events and death. Look AHEAD will determine whether lifestyle interventions designed to promote and sustain weight loss have an impact on reducing these outcomes.

Figure 5.

Baseline Medication Use by Education Group in the Look AHEAD Study. Data are expressed as percent of each educational group

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), the Office of Research on Minority Health, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute on Aging. In addition, the Indian Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provide support. All support to the clinical centers and the Coordinating Center was provided through the NIDDK using the mechanism of the Cooperative Agreement, except for the Southwestern American Indian clinical centers that are supported by the NIDDK directly. Finally, we are indebted to the thousands of people who volunteered to participate in the Look AHEAD Research Study and all of our colleagues in the health care community who provide medical services to the participants.

Writing Group: George Bray (Chair), Edward Gregg, Steven Haffner, F. Xavier Pi-Sunyer, Lynne E. Wagenknecht, Michael Walkup, Rena Wing

APPENDIX

Look AHEAD Research Group at Baseline

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Frederick Brancati, MD, MHS; Debi Celnik, MS, RD, LD; Jeff Honas, MS; Jeanne Clark, MD, MPH; Jeanne Charleston, RN; Lawrence Cheskin, MD; Kerry Stewart, EdD; Richard Rubin, PhD; Kathy Horak, RD

Pennington Biomedical Research Center George A. Bray, MD; Kristi Rau; Allison Strate, RN; Frank L. Greenway, MD; Donna H. Ryan, MD; Donald Williamson, PhD; Elizabeth Tucker; Brandi Armand, LPN; Mandy Shipp, RD; Kim Landry; Jennifer Perault

The University of Alabama at Birmingham Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH; Sheikilya Thomas MPH; Vicki DiLillo, PhD; Monika Safford, MD; Stephen Glasser, MD; Clara Smith, MPH; Cathy Roche, RN; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Nita Webb, MA; Staci Gilbert, MPH; Amy Dobelstein; L. Christie Oden; Trena Johnsey

Harvard Center

Massachusetts General Hospital: David M. Nathan, MD; Heather Turgeon, RN; Kristina P. Schumann, BA; Enrico Cagliero, MD; Kathryn Hayward, MD; Linda Delahanty, MS, RD; Barbara Steiner, EdM; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Ellen Anderson, MS, RD; Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Alan McNamara, BS; Richard Ginsburg, PhD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Theresa Michel, MS

Joslin Diabetes Center: Edward S. Horton, MD; Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE; Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD; A. Enrique Caballero, MD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE; Sarah Bain, BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN,RN; Lori Lambert, MS, RD

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: George Blackburn, MD, PhD; Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc; Ann McNamara, RN; Heather McCormick, RD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center James O. Hill, PhD; Marsha Miller, MS, RD; Brent VanDorsten, PhD; Judith Regensteiner, PhD; Robert Schwartz, MD; Richard Hamman, MD, DrPH; Michael McDermott, MD; JoAnn Phillipp, MS; Patrick Reddin, BA; Kristin Wallace, MPH; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; April Hamilton, BS; Salma Benchekroun, BS; Susan Green; Loretta Rome, TRS; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS

Baylor College of Medicine John P. Foreyt, PhD; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD; Henry Pownall, PhD; Peter Jones, MD; Ashok Balasubramanyam, MD; Molly Gee, MEd, RD

University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine Mohammed F. Saad, MD; Ken C. Chiu, MD; Siran Ghazarian, MD; Kati Szamos, RD; Magpuri Perpetua, RD; Michelle Chan, BS; Medhat Botrous

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

University of Tennessee East. Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH; Leeann Carmichael, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN

University of Tennessee Downtown. Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD; Jackie Day, RN; Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN; Debra Force, MS, RD, LDN; Debra Clark, LPN; Andrea Crisler, MT, Donna Green, RN; Gracie Cunningham; Maria Sun, MS, RD, LDN; Robert Kores, PhD; Renate Rosenthal, PhD; and Judith Soberman, MD

University of Minnesota Robert W. Jeffery, PhD; Carolyn Thorson, CCRP; John P. Bantle, MD; J. Bruce Redmon, MD; Richard S. Crow, MD; Jeanne Carls, MEd; Carolyne Campbell; La Donna James; T. Ockenden, RN; Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; M. Patricia Snyder, MA, RD; Amy Keranen, MS; Cara Walcheck, BS, RD; Emily Finch, MA; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh, CHES; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Tricia Skarphol, BS

St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD; Jennifer Patricio, MS; Jennifer Mayer, MS; Stanley Heshka, PhD; Carmen Pal, MD; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE

University of Pennsylvania Thomas A. Wadden, PhD; Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE; Gary D. Foster, PhD; Robert I. Berkowitz, MD; Stanley Schwartz, MD; Shiriki K. Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH; Monica Mullen, MS, RD; Louise Hesson, MSN; Patricia Lipschutz, MSN; Anthony Fabricatore, PhD; Canice Crerand, PhD; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Ray Carvajal, MS; Renee Davenport; Helen Chomentowski

University of Pittsburgh David E. Kelley, MD; Jacqueline Wesche -Thobaben, RN,BSN,CDE; Lewis Kuller, MD, DrPH.; Andrea Kriska, PhD; Daniel Edmundowicz, MD; Mary L. Klem, PhD, MLIS; Janet Bonk, RN, MPH; Jennifer Rush, MPH; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Barb Elnyczky, MA; Karen Vujevich, RN-BC, MSN, CRNP; Janet Krulia, RN ,BSN ,CDE; Donna Wolf, MS; Juliet Mancino, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Pat Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Anne Mathews, MS, RD, LDN

Brown University Rena R. Wing, PhD; Vincent Pera, MD; John Jakicic, PhD; Deborah Tate, PhD; Amy Gorin, PhD; Renee Bright, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Tammy Monk, MS; Kara Gallagher, PhD; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Maureen Daly, RN; Tatum Charron, BS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Linda Foss, MPH; Deborah Robles; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; Caitlin Egan, MS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Don Kieffer, PhD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Jane Tavares, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; JP Massaro, BS

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Steve Haffner, MD; Maria Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE; Connie Mobley, PhD, RD; Carlos Lorenzo, MD

University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB; Brenda Montgomery, MS, RN, CDE; Robert H. Knopp, MD; Edward W. Lipkin, MD, PhD; Matthew L. Maciejewski, PhD; Dace L. Trence, MD; Roque M. Murillo, BS; S. Terry Barrett, BS

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH; Paula Bolin, RN, MC; Tina Killean, BS; Cathy Manus, LPN; Carol Percy, RN; Rita Donaldson, BSN; Bernadette Todacheenie, EdD; Justin Glass, MD; Sarah Michaels, MD; Jonathan Krakoff, MD; Jeffrey Curtis, MD, MPH; Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP; Tina Morgan; Ruby Johnson; Janelia Smiley; Sandra Sangster; Shandiin Begay, MPH; Minnie Roanhorse; Didas Fallis, RN; Nancy Scurlock, MSN, ANP; Leigh Shovestull, RD

Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University School of Medicine Mark A. Espeland, PhD; Judy Bahnson, BA; Lynne Wagenknecht, DrPH; David Reboussin, PhD; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD; Wei Lang, PhD; Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH; Mara Vitolins, DrPH; Gary Miller, PhD; Paul Ribisl, PhD; Kathy Dotson, BA; Amelia Hodges, BS; Patricia Hogan, MS; Kathy Lane, BS; Carrie Combs, BS; Christian Speas, BS; Delia S. West, PhD; William Herman, MD, MPH

Central Resources Centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco Michael Nevitt, PhD; Ann Schwartz, PhD; John Shepherd, PhD; Jason Maeda, MPH; Cynthia Hayashi; Michaela Rahorst; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD; Greg Strylewicz, MS

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine Ronald J. Prineas, MD, PhD; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD; Charles Campbell, AAS, BS; Sharon Hall

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities Elizabeth J Mayer-Davis, PhD; Cecilia Farach, DrPH

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Barbara Harrison, MS; Susan Z. Yanovski, MD; Van S. Hubbard, MD PhD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Eva Obarzanek, PhD, MPH, RD; Denise Simons-Morton, MD, PhD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: David F. Williamson, PhD; Edward W. Gregg, PhD

Funding and Support

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women’s Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01-RR-02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center (M01-RR-01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00211-40); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR000056 44) and NIH grant (DK 046204); and the University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; Optifast ® of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

References

- 1.The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group The Diabetes Prevention Program: Baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1619–1629. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.11.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Look AHEAD Research Group Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2003;24:610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Look AHEAD intervention paper [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegal KM, et al. Excess deaths associated with overweight, underweight and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293:1861–1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Cadwell BL, Imperatore G, Williams DE, Flegal KM, Narayan KM, Williamson DF. Secular trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors according to body mass index in US adults. JAMA. 2005 Apr 20;293(15):1868–1874. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin BA, editor. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warnick GR. Enzymatic methods for quantification of lipoprotein lipids. Methods Enzymol. 1986;129:101–123. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)29064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-Mg2_ precipitation procedure for quantification of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1982;28:1279–1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hainline A Jr, Karon J, Lippel K, editors. Manual of Laboratory Operations. 2nd ed. Lipid Research Clinics Program, Lipid and Lipoprotein Analysis, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; [updated 1983]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Executive Summary of the Third Report. JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Galuska DA, Dietz WH. Trends and correlates of class 3 obesity in the United States from 1990 through 2000. JAMA. 2002 Oct 9;288(14):1758–1761. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colwell JA. Aspirin therapy in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S72–S73. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egede LE, Zheng D. Independent factors associated with major depressive disorder in a national sample. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:104–111. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin R, Knowler WC, Ma Y, Marrero DG, Edelstein SL, Walker EA, Garfield SA, Fisher EB Diabetes Program Prevention Research Group. Depression symptoms and antidepressant medicine use in Diabetes Prevention Program participants. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:830–837. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]