Abstract

20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) is an endogenous cytochrome P-450 product present in vascular smooth muscle and uniquely located in the vascular endothelium of pulmonary arteries (PAs). 20-HETE enhances reactive oxygen species (ROS) production of bovine PA endothelial cells (BPAECs) in an NADPH oxidase-dependent manner and is postulated to promote angiogenesis via activation of this pathway in systemic vascular beds. We tested the capacity of 20-HETE or a stable analog of this compound, 20-hydroxy-eicosa-5(Z),14(Z)-dienoic acid, to enhance survival and protect against apoptosis in BPAECs stressed with serum starvation. 20-HETE produced a concentration-dependent increase in numbers of starved BPAECs and increased 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation. Caspase-3 activity, nuclear fragmentation studies, and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assays supported protection from apoptosis and enhanced survival of starved BPAECs treated with a single application of 20-HETE. Protection from apoptosis depended on intact NADPH oxidase, phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)-kinase, and ROS production. 20-HETE-stimulated ROS generation by BPAECs was blocked by inhibition of PI3-kinase or Akt activity. These data suggest 20-HETE-associated protection from apoptosis in BPAECs required activation of PI3-kinase and Akt and generation of ROS. 20-HETE also protected against apoptosis in BPAECs stressed by lipopolysaccharide, and in mouse PAs exposed to hypoxia reoxygenation ex vivo. In summary, 20-HETE may afford a survival advantage to BPAECs through activation of prosurvival PI3-kinase and Akt pathways, NADPH oxidase activation, and NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide.

Keywords: reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphatase oxidase, reactive oxygen species, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Akt, hypoxia

cytochrome p-450 (cyp) enzymes can metabolize arachidonic acid into numerous eicosanoids, with the relative abundance dependent on the tissue and species (21). The major products in most tissues are the ω-hydroxylated metabolite 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) and regio- and stereo-specific epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. 20-HETE, a ω-hydroxylation product of arachidonic acid catalyzed by CYP4A, is a paracrine and autocrine mediator of numerous cellular processes (20, 29, 35). It is produced in vascular smooth muscle, renal, cerebral, pulmonary, mesenteric, and skeletal muscle beds and acts on the microvasculature and kidney tubules (11, 18, 22, 33, 38). Our laboratory has recently reported that 20-HETE/CYP4 enhances reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in bovine pulmonary artery (PA) endothelial cells (BPAECs) in a manner that is associated with activation of NADPH oxidase (24). 20-HETE has been linked to ROS production in other vascular beds (19), with 20-HETE-stimulated production of ROS being reported to exert either positive or negative effects in a tissue- and concentration-specific manner (e.g., Refs. 9, 17). In addition, NADPH oxidase is proposed to have a key role in growth and migration of human coronary endothelial cells, human umbilical vein endothelial cells, and dermal microvascular endothelial cells based on blunted proliferation in cells treated with inhibitors of NADPH oxidase or transgenic mice deficient in NADPH oxidase (1, 31).

Accordingly, we tested the capacity of 20-HETE and a stable analog of this lipid to increase cell survival and decrease apoptosis in BPAECs and ex vivo PAs, and the role of NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS in this protection. In these studies, we show for the first time that 20-HETE enhances survival of PAs and BPAECs through protection from apoptosis. 20-HETE-induced prosurvival effects depend on intact phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)-kinase (PI3K), Akt, and NADPH oxidase pathways. Inhibition of these pathways blocks 20-HETE-induced increases in ROS production, as well as 20-HETE-induced protection from apoptosis. Similarly, inhibition of ROS production blocks 20-HETE-induced protection against apoptosis. These data provide exciting new links between ROS production, NADPH oxidase activity, and activation of PI3K prosurvival pathways. They also raise the possibility that 20-HETE may play an important role in maintaining the integrity of the pulmonary vascular bed through ROS-mediated protection against apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Vybrant 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) Cell Proliferation Assay Kit was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, cat. no. v13154), caspase-3 Colorimetric Assay Kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, cat. no. BF3100), LPS from E. coli 0111:B4 from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, cat. no. L2630), Hoechst 33342 from Invitrogen (cat. no. v13244), wortmannin from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ, cat. no. 681675), Akt inhibitor from EMD Chemicals (cat. no. 124017), apocynin from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ, no. 178385), polyethylene glycolated superoxide dismutase (PEG SOD) from Sigma-Aldrich (cat. S-9549, 685 U/mg solid, one unit inhibited rate of reduction of cytochrome c by 50% in a coupled system with xanthine and xanthine oxidase at pH 7.8 at 25°C in a 3-ml reaction volume), and dihydroethidium (DHE) from Invitrogen (no. D11347). A protease inhibitor cocktail was obtained from Roche (Mannheim, Germany, cat. no. 1 836 170). Protein determination kit was obtained from BioRad (Hercules, CA, cat. no. 500-0006). DNA synthesis was determined according to the manufacturer's instructions (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, cat. no. 1647229) based on 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrDU) incorporation into newly synthesized DNA. 20-HETE and 20-hydroxy-eicosa-5(Z),14(Z)-dienoic acid, termed 20-5,14-HEDE in this work, were synthesized in the laboratory of Dr. J. R. Falck. The structures of these compounds appear as an inset in Fig. 3A. Since both 20-HETE and analog 20-5,14-HEDE yielded similar effects on the endpoint of MTT and caspase-3 activity in pilot experiments, one or the other, but not consistently both lipids, was used for investigations in this work.

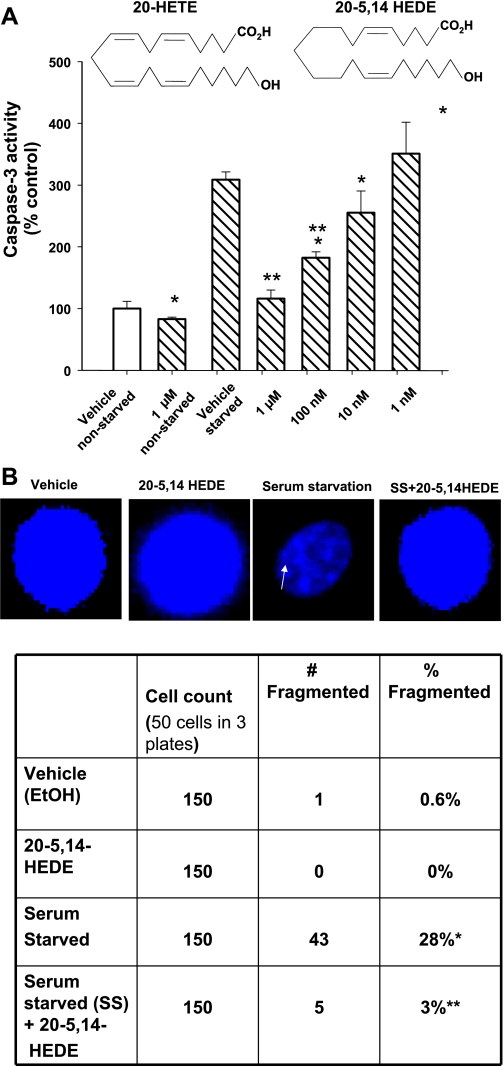

Fig. 3.

Analog of 20-HETE [20-hydroxy-eicosa-5(Z),14(Z)-dienoic acid (20-5,14-HEDE)] protects BPAECs against starvation-induced apoptosis. A: caspase-3 activity. We tested 20-5,14-HEDE against starvation-induced apoptosis in BPAECs. Starvation increases apoptosis, whereas 20-5,14-HEDE afforded protection against apoptosis at concentrations of 100 nM and 1 μM. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control. **P < 0.05 compared with SS cells (n = 5 groups of cells each). Inset: structures of 20-HETE and 20-5,14-HEDE. The double bonds between carbons 8, 9 and 11, 12 in 20-HETE are eliminated in 20-5,14-HEDE. B: Hoechst assays. These were performed on BPAECs treated with vehicle (ethanol) alone, 20-5,14-HEDE (1 μM), SS for 24 h, or SS with 20-5,14-HEDE added simultaneously. One hundred and fifty cells in randomly selected fields of each group in three different six-well plates were assessed for fragmentation of nuclei. Top: representative images of normal and fragmented nuclei. Bottom: counts of total numbers of cells and those having fragmented nuclei. No fragmentation of nuclei was observed in cells treated with 20-5,14-HEDE. SS was associated with an increase in nuclear fragmentation (28% of cells in this group). Addition of 20-5,14-HEDE reduced the percentage of fragmented nuclei to 3% (P < 0.05 relative to SS alone). These data support protection from apoptosis induced by SS with 20-5,14-HEDE. n = 3 studies for each treatment group, with 50 cells analyzed in each study.

A chimeric peptide, which inhibits association of p47phox with gp91 in NADPH oxidase, was synthesized by our protein core, according to the sequence defined by Rey et al. (28) to test the contribution of NADPH oxidase to ROS production. The sequence of this peptide is [H]-R-K-K-R-R-Q-R-R-R-C-S-T-R-I-R-R-Q-L-NH2. The sequence of the scrambled (control) peptide is R-R-Q-R-R-R-C-L-R-I-T-R-Q-S-R-NH2.

Growth and culture of BPAEC.

BPAEC derived from tissue obtained at a local abattoir were isolated (38) and cultured in RPMI media (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Hyclone, Logan, UT) in 100-mm2 dishes. All cells were used between passages 2 and 5 for experiments in this study.

Serum starvation experiments.

BPAECs that were 60–80% confluent in 24-well plates were starved with serum-free media for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 20-HETE in concentrations ranging from 0.1 nm to 50 μM or ethanol (vehicle) in triplicate for an additional 18–24 h. Cells were detached with trypsin and manually counted using a hemocytometer to determine cell numbers for some experiments. In other experiments, MTT+, Hoechst, or caspase activities were measured, as detailed below.

DNA synthesis determination.

We determined DNA synthesis by measuring the incorporation of BrdU into cells using a BrdU proliferation kit (Boehringer Mannheim). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at an initial density of 4,000/well in DMEM with 20% FBS for 24–48 h until they were 70% confluent. They were next starved for 24 h, then treated with 20-HETE in varying concentrations, vehicle, or VEGF, or returned to complete media for 24 h in a similar way to the cell count method. At the end of this time, wells were washed and incubated with BrdU for 4 h, then assessed at absorbance at 370 nm with a reference wavelength of 492 nm in a plate reader, as described by the manufacturer's instructions.

MTT assays.

For MTT assays, cells were incubated with yellow mitochondrial dye, MTT+. Colorimetric conversion of yellow MTT+ to blue formazan dye is proportional to the number of live cells present and represents protection from apoptosis. The absorbance was read at 540 nm in a spectrophotometer, which determines the intensity of color.

Apoptosis measured by caspase-3 activity.

Kits are from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). BPAECs were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in lysis buffer [5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)], and stored overnight at −80°C. After centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min, the supernatant was used for determining caspase-3 activity using DEVD-pNA as substrate, according to the manufacturer's protocol (8).

Ex vivo PAs.

Methods for obtaining and treating mouse PAs are detailed below. PAs were processed as directed for the caspase-3 colorimetric assay (R&D Systems) by homogenization in the lysis buffer provided and centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min. The supernatants of BPAECs or PA homogenates were used for determining caspase-3 activity using DEVD-pNA as substrate (8).

Hoechst stain.

Cells were cultured in six-well plates to ∼70% confluence. Wells were washed, and cells incubated in serum-free media containing vehicle or 20-5,14-HEDE for 8 h. After that time, vehicle or LPS along with 20-5,14-HEDE vehicle or 20-5,14-HEDE were added for another 16 h. For serum starvation experiments, cells were serum starved for 24 h, with or without application of 20-5,14-HEDE at the beginning of serum starvation and once after 16 h. At the end of the experiments, cells were stained with 1 μl of Hoechst 33342 (5 mg/ml, Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, V-13244) in 1 ml basal medium and incubated for 30 min. Stained cells were then washed twice with PBS (Sigma) and imaged under a fluorescent microscope using a 460-nm filter after excitation at 530 nm for assessment of nuclear fragmentation.

LPS experiments.

BPAEC passages 2–5 were changed to 5% serum-containing media, then pretreated with either vehicle or 20-5,14-HEDE (1 μM). Cells were maintained in this environment for 8 h, then 5 μg/ml LPS at a final concentration with vehicle, or LPS with 20-5,14-HEDE (also 1 μM) were added for another 16 h. At the end of 16 h, cells were harvested for caspase-3, Hoechst, or MTT assays.

Hypoxia/reoxygenation of PAs.

Microdissected mouse PA rings (2–5 mm in length) were placed in Dulbecco's modified essential medium, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma, low endotoxin and fatty acid grade) and 10 mM 2-deoxyglucose. One micromole of 20-HETE or 20-5,14-HEDE was added immediately before hypoxia was initiated, while ethanol was used as the vehicle. The rings were maintained at 37°C under an atmosphere of 95% N2 and 5% CO2 (hypoxia) or 95% air and 5% CO2 (normoxia) for 8 h, followed by reoxygenation for 16 h. The oxygen content during hypoxia (inspired O2 fraction) was continuously monitored (Pro-Ox 110, Biospherix, Redfield, NY) and did not measure above 2% at any time.

Detection of ROS by fluorescence microscopy.

Primarily isolated BPAECs from passages 2–5 were used for these assays. Cells were cultured in 35-mm dishes to ∼70% confluence. Inhibitors of ROS were applied 30 min before loading with the fluorescent dye DHE (final concentration 10 μM). Three to four images were acquired for each dish with a Nikon Eclipse TE200 microscope equipped with fluorescence attachment (Lambda DG-4 from Sutter Instrument) and captured using a Hamamatsu digital camera C4742–95. Approximately 20 cells were randomly selected in each field, and average fluorescent intensity within operator-defined cell borders was recorded using Metamorph version 6.2 software, as previously described (24). Background fluorescence was estimated by capturing an image in an area free of cells and subtracted from the fluorescence intensity of cells on the same slide.

Statistics.

Pooled data from each experiment were used to calculate the means ± SEs for control (vehicle treated) or experimental (treated with 20-HETE or 20-5,14-HEDE) samples. The data were tested for significance by one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak's, Tukey's, or Fischer's post hoc tests for more than two study groups, or a Student's t-test (for unpaired samples) using the Jandel, SigmaStat Software. Experiments with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Serum-starved BPAECs exhibit enhanced survival with 20-HETE.

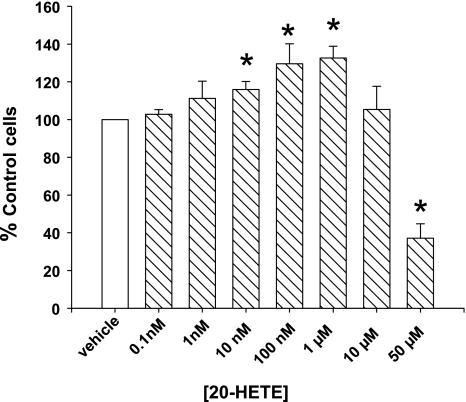

A single application of 20-HETE to serum-starved BPAECs resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in cell numbers 18–24 h after treatments (Fig. 1). The peak response was observed in cells treated with 1 μM 20-HETE, although a significant increase in cell number was observed at 10 and 100 nM concentrations as well. Fifty micromoles of 20-HETE decreased survival of cells over that of cells treated with vehicle alone.

Fig. 1.

20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) increases survival of serum-starved (SS) pulmonary artery (PA) endothelial cells. Bovine PA endothelial cells (BPAECs) were cultured in serum-free media containing 20-HETE (final concentrations on the X-axis) or ethanol (vehicle) for 24 h. Following 24 h, cells were detached with trypsin and manually counted using a hemocytometer. Experimental data points represent an average count of 4 wells each from 4 different experiments, using at least 2 independent isolates of cells. A concentration-dependent increase in cell numbers was observed in BPAECs treated with 20-HETE, which peaked between 100 nM and 1 μM, and dropped off thereafter. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with control (vehicle).

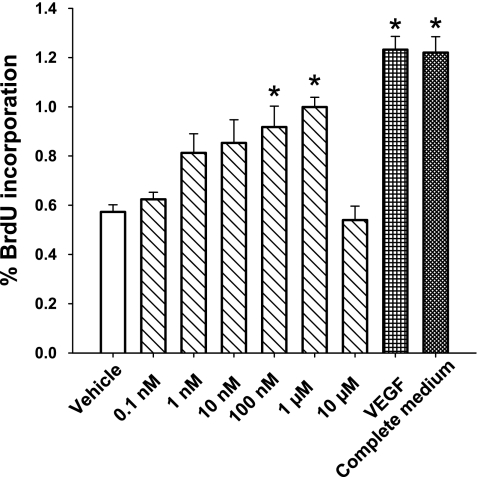

To examine the potential contribution of proliferation to the increase in number of cells, incorporation of BrDU into newly synthesized DNA was examined (Fig. 2). VEGF (20 ng/ml) and complete media were used as positive controls. 20-HETE increased BrDU incorporation over that of vehicle alone at concentrations of 100 nM and 1 μM. These data support the potential of 20-HETE to promote proliferation in BPAECs.

Fig. 2.

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrDU) incorporation was measured as an index of cell proliferation. Cells in 96-well plates were starved for 24 h, then treated with 20-HETE in final concentrations, which appear on the X-axis, 20 ng/ml VEGF, or complete media for an additional 24 h. At the end of that time, BrDU incorporation was assessed by absorbance at 370 nm with a reference wavelength of 492 nm. Each data point represents 4 different experiments with triplicates of each condition in all 4 experiments. SS decreased BrDU incorporation relative to that of cells treated with VEGF or complete media. At concentrations of 100 nM and 1 μM, 20-HETE increased BrDU incorporation over that of vehicle-treated SS cells. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with control (vehicle).

Caspase-3 activity of serum-starved cells is decreased by 20-HEDE in a concentration-dependent manner. Since cell numbers can be increased both by proliferation and enhanced survival, we next tested the effect of an analog of 20-HETE, 20-5,14-HEDE, to protect against apoptosis, as detected by caspase-3 activity. The chemical structures of 20-HETE and 20-5,14-HEDE appear as an inset in Fig. 3A. Caspase-3 activity of BPAECs was increased by starvation and decreased by a single application of 20-5,14-HEDE at concentrations of 100 nM and 1 μM (Fig. 3A). Treatment with 1 μM 20-5,14-HEDE decreased caspase-3 activity in nonstarved cells over that of cells treated with vehicle alone. These data support 20-HETE- or 20-5,14-HEDE-associated enhanced cell survival and decreased apoptosis in starved BPAECs.

To assess apoptosis with a separate assay, Hoechst staining was performed to test for DNA fragmentation (Fig. 3B). Serum-starved cells demonstrated DNA fragmentation. In contrast, cells treated with 20-5,14-HEDE during starvation did not show any DNA fragmentation, thereby indicating protection of cells from apoptosis by 20-5,14-HEDE using two different assays. From this point forward, our studies focused on the anti-apoptotic effects of these lipids. The concentration of 20-HETE or 20-5,14-HEDE, resulting in the maximum effect on survival and protection from apoptosis (1 μM), was used to examine mechanisms of protection from apoptosis.

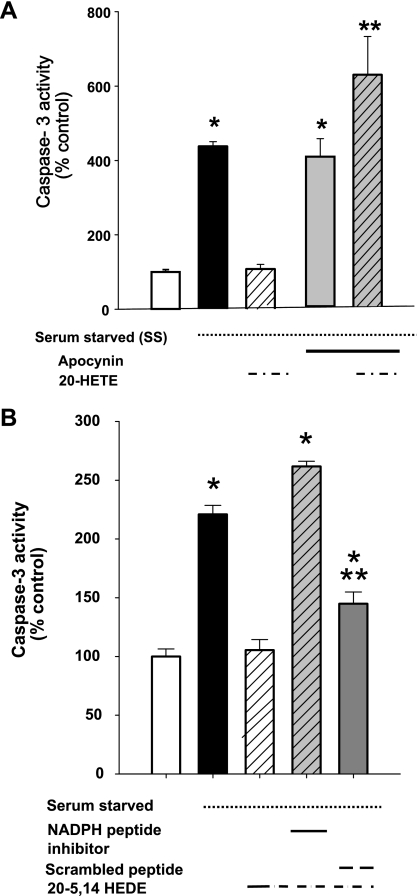

Mechanism of protection against caspase-3 activation: role of NADPH oxidase.

Our data have demonstrated 20-HETE-associated activation of NADPH oxidase in BPAECs (24), as well as NADPH-dependent activation of ROS by 20-HETE in these cells. We next asked the question if protection by 20-HETE from starvation was dependent on NADPH-oxidase activity. 20-HETE-associated protection from starvation was effectively blocked by 1 μM apocynin, suggesting a requirement for intact NADPH oxidase activity for salutary effects by this lipid (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

NADPH oxidase is required for 20-HETE-afforded protection against apoptosis in SS BPAECs. A: we tested the impact of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin (1 μM) on starvation-induced apoptosis in BPAECs. In data not shown, apocynin alone had no effect on caspase-3 activity in nonstarved cells (mean = 95% nonstarved controls; n = 4; P > 0.05). Starvation increased caspase-3 activity and 20-HETE protected against this increase. SS cells treated with apocynin (1 μM) had caspase-3 activity that was not different than starvation alone. Moreover, cells treated with both apocynin and 20-HETE (1 μM) did not enjoy the protection afforded to cells treated with 20-HETE alone. The caspase-3 activities were higher for cells treated with 20-HETE and apocynin than those of SS cells treated with vehicle alone. B: peptide-based inhibitor of NADP oxidase. Treatment with a peptide-based inhibitor, which blocks the association of p47 to gp91 (28), eliminated 20-HETE-induced protection of BPAECs from starvation compared with a scrambled peptide, which served as a negative control. Values are means ± SE; n = 10 (A) and n = 6 (B) for each group. *P < 0.05 compared with non-SS cells; **P < 0.05 compared with SS cells.

To exclude potential nonspecific effects of apocynin, we tested the ability of a peptide-based inhibitor to eliminate 20-HETE-induced protection of BPAECs from starvation (Fig. 4B). These data showed loss of the protective effect of 20-5,14-HEDE from starvation-induced increases in caspase-3 in cells pretreated with a peptide-based inhibitor of NADPH oxidase (28), although not a scrambled peptide, which served as a negative control.

Role of PI3K in protection against starvation-associated apoptosis.

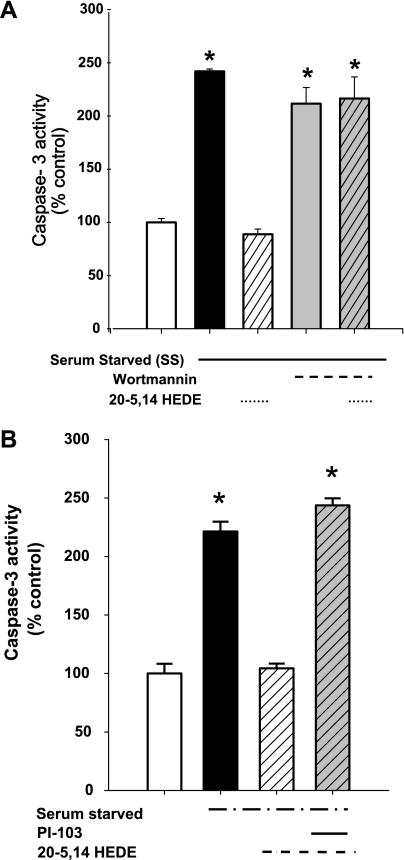

PI3K is a strong survival pathway associated with activation of NADPH oxidase in various cell systems, including normoxic lung ischemia (37). Our laboratory has previously reported 20-HETE-induced activation of PI3K, Akt, and Rac (5, 24). Accordingly, we tested the role of PI3K in 20-HETE-associated protection against caspase activity in serum-starved BPAECs (Fig. 5A). Treatment with wortmannin (100 nM) offered no protection over vehicle alone in starved cells. Furthermore, treatment with wortmannin blocked 20-HETE (1 μM) associated protection of starved BPAECs, evoking participation of this novel signaling pathway in this injury model. To further examine the contribution of PI3K to 20-HETE-evoked protection from apoptosis, a second inhibitor of PI3K, PI-103 (100 nM), was employed in similar experiments (Fig. 5B; Ref. 3). Like wortmannin, treatment with PI-103 blocked 20-5,14-HEDE-associated protection from starvation-induced increases in caspase-3.

Fig. 5.

Phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)-kinase activity is required for protection by 20-5,14-HEDE against starvation-induced apoptosis in BPAECs. In data not shown in the graph, wortmannin (100 nM) alone had no effect on caspase-3 activity in nonstarved BPAECs (mean = 109% nonstarved values; n = 4; P > 0.05). A: 20-5,14-HEDE (1 μM) protects against starvation-associated increase in caspase-3 activity. Wortmannin (100 nM) alone in starved cells offered no protection over that of vehicle alone. Treatment with wortmannin blocked protection by 20-5,14-HEDE. *P < 0.05 relative to control (with serum) and SS+20-HEDE (n = 6 for each group). B: like wortmannin, the PI3-kinase inhibitor PI-103 (100 nM) blocks 20-5,14-HEDE protection from starvation-evoked increases in caspase-3 activity in BPAECs. Values are means ± SE; n = 5 each group. *P < 0.05 relative to nonstarved control group.

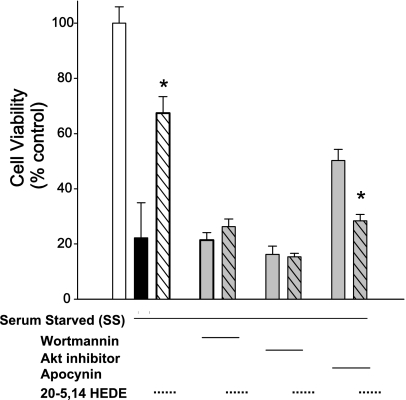

Role of PI3K, Akt pathways, and NADPH oxidase in 20-HETE-enhanced survival, as evidenced by MTT assays.

Inhibitors of NADPH oxidase, Akt, and PI3K were tested for their effects on cell survival in serum-starved BPAECs (Fig. 6). In these assays, 20-5,14-HEDE afforded protection against death, as quantitated by MTT assays. Wortmannin (100 nM), Akt inhibitor (10 μM), or apocynin (1 μM) alone had no significant effect on MTT reduction in starved cells. However, protection against starvation by 20-5,14-HEDE (1 μM) was lost in all cell cohorts treated with any of these three agents, suggesting a role for PI3K and NADPH in 20-HETE-induced cell survival, as well as caspase-3 activation. Together with Figs. 4 and 5, these data provide evidence from two different types of assays and two mechanistically distinct inhibitors to support a role for PI3K, Akt, and NADPH oxidase in protection of BPAECs from apoptosis induced by starvation.

Fig. 6.

3-[4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays in BPAECS treated with wortmannin, Akt inhibitor, or apocynin. As a separate index of cell survival, MTT reduction was measured in BPAECs stressed with starvation. Starvation (18 h) followed by a single application of 20-HETE vehicle (ethanol) decreased MTT signal (measured 24 h later) to ∼20% that of nonstarved controls, consistent with injury. A single application of 20-5,14-HEDE provided significant protection. Wortmannin (100 nM), Akt inhibitor (10 μM), or apocynin (1 μM) alone afforded no protection over vehicle in SS cells. Treatment with any of these agents blocked protection afforded by 20-5,14-HEDE, supporting a role for activation of PI3-kinase and NADPH oxidase in these cells. Values are means ± SE; n = 8 for all experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with matched SS control. In data not shown, 10 μM of the Akt inhibitor had no effect on caspase-3 activity in nonstarved cells (mean = 116% nonstarved vehicle; n = 3).

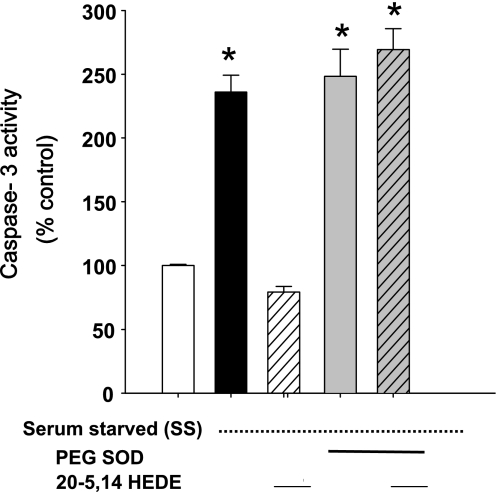

Role of ROS in 20-HETE-induced protection against apoptosis.

Our laboratory's previous investigations have shown that 20-HETE increases superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production in BPAECs (24), an effect attributable significantly to NADPH oxidase. To determine the role of superoxide in 20-HETE-induced protection against apoptosis, caspase-3 activity was measured in BPAECs treated with 20-5,14-HEDE and simultaneously with PEG SOD (100 units) or vehicle (Fig. 7). Treatment with PEG SOD blocked 20-HETE-afforded protection against starvation-induced increase in caspase-3 activity. These data suggest a role for superoxide in protection by 20-HETE against starvation-induced apoptosis.

Fig. 7.

Caspase-3 activity in SS BPAECs is blocked by polyethylene glycol (PEG) superoxide dismutase (SOD). In data not shown, PEG SOD (100 units) had no effect on caspase-3 activity in nonstarved cells (mean = 114% nonstarved control; n = 3). SS cells treated with PEG SOD (100 units) exhibited an increase in caspase-3 activity that was similar to that of SS cells treated with vehicle alone. Treatment with both PEG SOD and 20-5,14-HEDE resulted in caspase-3 activity that was identical to that of starved cells. Values are means ± SE; n = 6 for all groups. *P < 0.05 compared with non-SS controls.

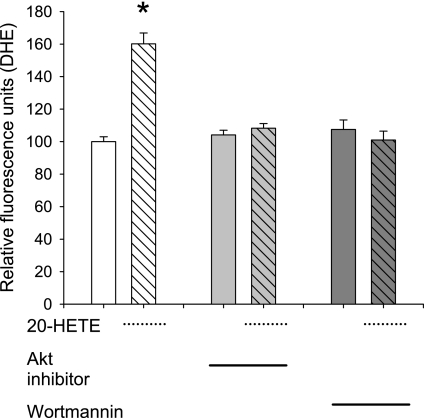

Wortmannin and Akt inhibition block 20-HETE-evoked superoxide production.

If PI3K and Akt mediate 20-HETE-afforded protection against apoptosis via generation of superoxide, inhibition of these pathways should block 20-HETE-evoked increases in ROS. Our laboratory has previously reported that apocynin and a peptide-based inhibitor of NADPH oxidase block DHE-detected, 20-HETE-induced increases in superoxide (24). Serum starvation alone increased DHE fluorescence by 26%, consistent with activation of a prosurvival pathway (n = 120 cells per group; data not shown as a figure). All data testing the effects of inhibitors on DHE fluorescent intensity were obtained in serum-starved cells. As observed in Fig. 8, 20-HETE increases superoxide production in BPAECs, and treatment with either wortmannin or Akt inhibitor (Fig. 8) block this release. Together, these data support a role for 20-HETE-evoked, PI3K and Akt-dependent increases in ROS, which contribute to prosurvival effects of this agent.

Fig. 8.

20-HETE induced superoxide production depends on PI3-kinase and Akt. BPAECs were loaded with dihydroethidium (DHE) to track superoxide generation. Fluorescence intensity was normalized to that of cells treated with 20-HETE vehicle alone (ethanol). All BPAECs loaded with DHE exhibit 20-HETE (1 μM) induced increases in signal, consistent with superoxide generation. Pretreatment of cells for 20 min with 100 nM wortmannin or 10 μM Akt of the Akt inhibitor alone to inhibit PI3-kinase had no effect on DHE fluorescence. However, pretreatment with either wortmannin or the Akt inhibitor blocked 20-HETE-induced increase in DHE fluorescence. Values are means ± SE; n ≥ 65 cells in each group taken from at least 2 independent isolates of BPAECs. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle.

LPS-induced stress: a second model of injury.

To test the capacity of 20-HETE to enhance cell survival or protect against apoptosis in a second model of injury, BPAECs were pretreated with vehicle or 20-5,14-HEDE for 8 h. Then vehicle, LPS (0.5 μg/ml), or LPS + 20-5,14-HEDE were added for an additional 16 h, after which time the MTT assays were completed. Pretreatment with 20-5,14-HEDE increased survival of cells over vehicle alone in this model, while LPS decreased the same (Fig. 9). 20-5,14-HEDE offered protection of BPAECs exposed to LPS over vehicle alone.

Fig. 9.

Treatment with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) decreased survival, and 20-5,14-HEDE protects. BPAECs were maintained in media with 5% FBS and vehicle, 20-5,14-HEDE (1 μM) alone, endotoxin LPS (0.5 μg/ml) alone for 8 h, or LPS + 20-5,14-HEDE added simultaneously with the LPS. After 8 h, cells were harvested, and MTT assays to assess survival were performed. 20-5,14-HEDE alone increased survival over that of cells maintained in media alone. LPS alone decreased MTT, but simultaneous treatment with 20-5,14-HEDE protected against LPS-induced loss of MTT uptake. Values are means ± SE; n = 5 in each group. *P < 0.05 compared with vehicle control; #P < 0.05 compared with 20-HEDE.

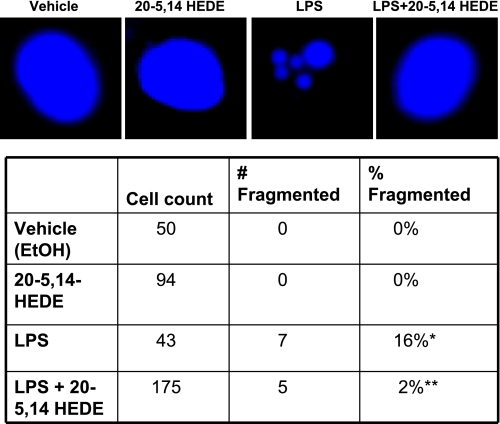

To further study the effect of 20-5,14-HEDE in BPAECs treated with LPS, Hoechst assays were performed on the same groups of cells as detailed above for caspase-3 experiments. Fragmentation of nuclei was absent in cells treated with vehicle or 20-5,14-HEDE alone and noted in 16% of cells treated with LPS and 2% of cells pretreated with 20-5,14-HEDE and then LPS (Fig. 10). Thus two independent assays support a survival advantage of BPAECs stressed with LPS and treated with 20-5,14-HEDE.

Fig. 10.

Hoechst assays demonstrate protection of BPAECs injured by LPS when treated with 20-5,14-HEDE. Hoechst assays were performed on BPAECs treated with vehicle alone (control), 20-5,14-HEDE (1 μM), LPS (0.5 μg/ml) for 8 h, or LPS + 20-5,14-HEDE added simultaneously. Cells in 4 randomly selected fields of each group were assessed for fragmentation of nuclei. Top: representative images of normal and fragmented nuclei. Bottom: counts of total numbers of cells and numbers of fragmented nuclei. No fragmentation of nuclei was observed in cells treated with vehicle or 20-5,14-HEDE. LPS was associated with an increase in nuclear fragmentation. Addition of 20-5,14-HEDE to LPS reduced the percentage of fragmented nuclei to 2%. Values are means ± SE; n = 3 experiments for each group. These data support protection from apoptosis induced by LPS by 20-5,14-HEDE. *P < 0.05 compared with 20-5,14-HEDE; **P < 0.05 relative to LPS.

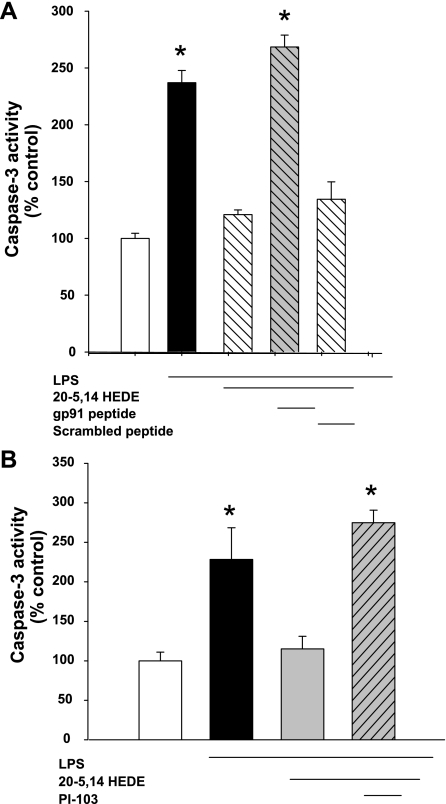

To examine the contribution of NADPH oxidase and PI3K to 20-HETE protection from apoptosis evoked by LPS, BPAECs stressed with LPS were treated with the gp91 peptide-based inhibitor (Fig. 11A) or PI-103 (Fig. 11B). Both of these agents blocked the protection afforded by 20-5,14-HEDE against LPS-associated increases in caspase-3 activity.

Fig. 11.

LPS-induced increases in caspase-3 activity depend on NADPH oxidase and PI3-kinase. A: caspase-3 activity was measured in BPAECs treated with vehicle, LPS (1 μg/ml), LPS + 20-5,14-HEDE, or LPS + 20-5,14-HEDE + gp91 peptide inhibitor (n = 5 each group). LPS resulted in an increase in caspase-3 activity, and 20-5,14-HEDE protected from LPS-induced apoptosis. Treatment with the gp91 peptide inhibitor to block NADPH oxidase eliminated 20-5,14-HEDE-evoked protection, while the scrambled peptide had no effect. B: caspase-3 measurements were obtained in BPAECs treated with vehicle, LPS (1 μg/ml), LPS + 20-5,14-HEDE, or LPS + 20-5,14-HEDE + PI-103 (100 nM final concentration; n = 6 each group). Treatment with PI-103 blocked 20-5,14-HEDE-associated protection from LPS-induced rise in caspase-3. Together, these data support a role for both NADPH oxidase and PI3-kinase in 20-5,14-HEDE protection from LPS-induced apoptosis. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 relative to vehicle control in both A and B.

Caspase-3 activity in hypoxic ex vivo PAs: a third model of injury.

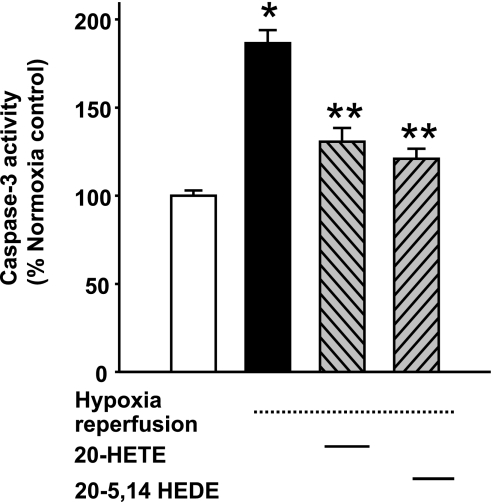

We investigated the capacity of 20-HETE to protect against hypoxia-reperfusion (HR)-induced injury of ex vivo PAs. Caspase-3 activity was examined in ex vivo PAs stressed with hypoxia for 8 h followed by 16-h reoxygenation, treated with 1 μM 20-HETE, 20-5,14-HEDE, or vehicle added immediately before hypoxia exposure. HR increased caspase-3 activity over that of PAs maintained in normoxic environment, and both 20-HETE and 20-5,14-HEDE decreased caspase-3 measurement relative to those of HR-exposed vessels (Fig. 12). These data demonstrate 20-HETE- and 20-5,14-HEDE-induced protection from apoptosis in ex vivo PAs subjected to HR.

Fig. 12.

Caspase-3 activity in ex vivo PAs. Caspase-3 activity was measured in ex vivo PAs with 4 test conditions: normoxia (control) with vehicle, hypoxia-reperfusion (HR) with vehicle (see materials and methods for details), HR with 1 μM 20-HETE, or HR with 1 μM 20-5,14-HEDE, all added only once, just before exposure to hypoxia. HR increased caspase-3 activity. Both 20-HETE and 20-5,14-HEDE afford protection against the increase in caspase-3 activity. Values are means ± SE; n = 4 for each group. *P < 0.05 compared with control; **P < 0.05 compared with HR.

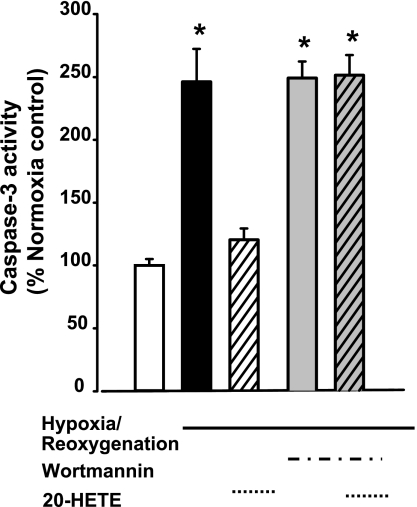

Role of PI3K in 20-HETE enhanced survival of hypoxic ex vivo PAs.

To examine mechanisms through which 20-HETE afforded a prosurvival advantage in ex vivo PAs exposed to HR, we first evaluated the contribution of PI3K to salutary effects of 20-HETE in this model. Treatment with the inhibitor wortmannin (200 nM) eliminated the protection against HR afforded by 20-HETE (Fig. 13). These observations support the contribution of PI3K activation in 20-HETE-evoked protection in ex vivo PAs.

Fig. 13.

PI3-kinase activity is required for protection of ex vivo PAs by 20-HETE from HR-induced injury. Caspase 3 activity was measured in ex vivo PAs, as well as those stressed with HR, 20 HETE (1 μM), wortmannin (200 nM), or wortmannin + 20-HETE. 20-HETE and wortmannin were added just before hypoxia. HR increased caspase-3 activity, and 20-HETE protected against this increase. Treatment with wortmannin alone afforded no protection against HR injury, and dual treatment of cells exposed to HR with wortmannin and 20-HETE did not reduce caspase-3 activity over that of wortmannin or vehicle. Values are means ± SE; n = 4 for each group. *P < 0.05 compared with control.

DISCUSSION

We report here for the first time that 20-HETE exerts prosurvival effects, as indicated by three separate assays, MTT uptake (enhanced cell survival), Hoechst stains (estimation of nuclear fragmentation), and caspase-3 activity (common pathway for apoptosis), in BPAECs stressed by either serum starvation or LPS. In addition, the protective effect of 20-HETE extends to ex vivo PAs exposed to hypoxia reoxygenation (HR). However, high concentrations of 20-HETE (above 1 μM) do not support cell survival and, in fact, decrease numbers of cultured BPAECs. Guo et al. (14) described proliferative, but not antiapoptotic effects of 20-HETE mediated by VEGF in human dermal microvascular cells. In a separate study, however, this group reported antiproliferative effects of HET0016 (an inhibitor of the formation of 20-HETE) in gliosarcoma cells in vivo and in vitro (15). Our studies support a pro-proliferative effect of 20-HETE in BPAECs, but we focused on the mechanisms through which this lipid promotes survival in these cells. Wang et al. (34) recently reported antiapoptotic effects of 20-HETE in PA vascular smooth muscle cells, but no mechanisms of protection other than activation of the intrinsic pathway were reported. Nilakantan et al. (26) observed enhanced ischemia-reperfusion injury in renal epithelial cells overexpressing CYP4A, an isoform that catalyzes the conversion of arachidonic acid into 20-HETE. These results may be similar to our observations of serum-starved BPAECs exposed to 50 μM 20-HETE, which decreased cell numbers. To our knowledge, the data in the present work represent the first report of proliferative actions of 20-HETE in BPAECs, as well as the first antiapoptotic effects of 20-HETE in PA endothelial cells. Moreover, it is the first report of 20-HETE-associated activation of PI3K and prosurvival benefits depending on this pathway for production of ROS.

Our laboratory previously identified 20-HETE-induced stimulation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in BPAECs and showed that PEG SOD or PEG catalase blocks superoxide production in these cells (24). Thus we were interested to test whether ROS were required for 20-HETE-associated protection against apoptosis. This work now demonstrates that treatment of cells with PEG SOD to rapidly dismutate superoxide production stimulated by 20-HETE effectively eliminated the protective effect of this lipid on starvation-evoked apoptosis in BPAECs, providing strong evidence for the role of ROS in this process.

There is precedent for ROS either stimulating growth or promoting cell survival. ROS, including superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, signal growth and migration, activation of transcription factors, and activation of protein kinases, including ERK, p38 MAPK, and Akt (17). Nanomolar to micromolar concentrations of hydrogen peroxide stimulate proliferation and migration of bovine aortic endothelial cells (36). Human coronary and dermal microvascular endothelial cells require ROS derived from NADPH oxidase for proliferation and migration (1). Angiogenesis induced by VEGF suffused subcutaneously implanted sponges is deficient in Nox2 knockout mice, implicating both NADPH oxidase and ROS in this process (31). Thus, despite well-recognized tissue injury associated with unchecked generation of ROS (10, 16), it is clear that modest levels of ROS are required for growth or protection against apoptosis.

ROS are produced from several cellular sources, including mitochondrial electron transport chain, xanthine oxidase, CYP, uncoupled nitric oxide synthase, and NADPH oxidases (27). Hyperoxia induces ROS from mitochondrial sources in pulmonary capillary endothelial cells, but subsequently activates NADPH oxidase through calcium-dependent and Rac-1-dependent mechanisms (4), supporting key roles for both mitochondrial and NADPH oxidase pathways in these cells. CYP4 is postulated to promote angiogenesis via NADPH oxidase-dependent mechanisms in systemic vascular beds (2, 23). NADPH oxidase catalyzes the NADPH-dependent, one-electron reduction of molecular oxygen to superoxide. In its activated form, NAPDH oxidase is a multimeric protein consisting of at least three cytosolic subunits, including p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, either Rac1 or Rac2, and a membrane-associated cytochrome reductase complex consisting of gp91phox and p22phox (6, 13). Our studies have demonstrated that 20-HETE enhances expression and membrane association of p47phox and gp91phox in BPAECs (24). Moreover, 20-HETE-associated increase in ROS production is blocked by apocynin, supporting a key role for NADPH oxidase in this process (24). In the present investigations, we now provide the first evidence that 20-HETE-enhanced survival and decreased apoptosis of BPAECs stressed by starvation depend on intact NADPH oxidase, since treatment of cells with apocynin or a gp91 peptide-based inhibitor largely eliminates protection afforded by this lipid.

The PI3K/Akt pathway provides a link between extracellular survival signals and apoptosis pathways within the cells. Activation of receptor tyrosine kinases leads to phosphorylation and activation of PI3K and formation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate then recruits the protein kinase Akt to the plasma membrane, where it is activated as a result of phosphorylation by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase (PDK). Akt then appears to phosphorylate a number of proteins that contribute to cell survival. Thus PI3K/Akt is a well-recognized prosurvival pathway (7).

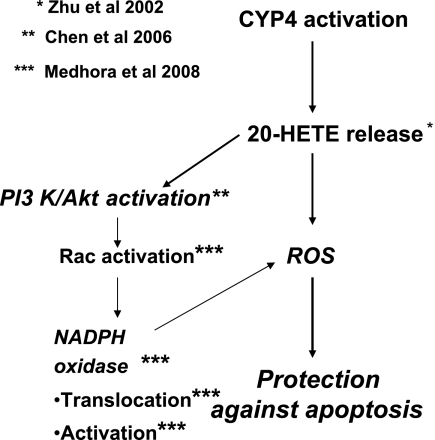

Our published data demonstrate VEGF and 20-HETE-mediated phosphorylation of Akt in BPAECs (5). We, therefore, postulated that 20-HETE activates PI3K/Akt, which, in turn, stimulates NADPH oxidase in BPAECs. In the present study, we show that prosurvival or antiapoptotic effects of 20-HETE are blocked by wortmannin, PI-103, or an Akt inhibitor, supporting a direct role for this signaling pathway in 20-HETE protection from cell death. These data evoke a new survival pathway stimulated by 20-HETE. 20-HETE has reported to increase the activities of MAPK and cytosolic PLA2 and promote translocation of Ras in vascular smooth muscle cells (25). It was postulated that activation of Ras/MAPK by 20-HETE amplifies cytosolic PLA2 activity and releases additional arachidonic acid (AA) by a positive feedback mechanism, thereby promoting cell proliferation and growth (32). A schematic depicting our hypothesized signaling pathways activated by 20-HETE via NADPH oxidase that leads to prosurvival/antiapoptotic effects in BPAECs appears in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.

Schematic of hypothetical signaling pathway linking cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 4 activation and 20-HETE-induced protection from apoptosis. Our laboratory has previously shown 20-HETE to be generated by CYP4 activation in PA endothelial cells (38). Our laboratory's prior studies have also demonstrated that 20-HETE activates Rac and translocates NADPH oxidase, generates ROS in an NADPH oxidase-dependent manner (24), and activates Akt (5). In this study, we hypothesized that 20-HETE protects BPAECs from apoptosis through activation of PI3 and Akt and through generation of ROS. Our results provide evidence that 20-HETE activates the pathways as they appear in the schematic, together resulting in decreased apoptosis through ROS-dependent mechanisms.

Expression of 20-HETE-forming isoforms is tissue specific, and biological functions of 20-HETE outside the lung are not all salutary. For example, 20-HETE formation in cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells of spontaneously hypertensive rats is reported to contribute to the severity of oxidative stress and strokes (9). In a similar model, hypoxia leads to increased ROS formation in cerebral vascular smooth muscle, which, in turn, decreases 20-HETE formation and promotes dilation of cerebral arterioles (12). Although our data suggest a prosurvival effect of 20-HETE on BPAECs stressed by starvation, LPS, and HR, these injuries are believed to result in cell death by distinct mechanisms. While LPS is believed to initiate apoptosis via activation of Fas ligands, HR causes cell loss through not only apoptosis, but also oncosis and necrosis (30). Our data support a role for PI3K and NADPH oxidase in 20-HETE protection from LPS. The role of other signaling pathways (e.g., oncosis) in cells stressed with LPS or hypoxia and treated with 20-HETE has not been examined.

In conclusion, these studies report, for the first time, antiapoptotic effects of 20-HETE against three forms of injury, which are serum deprivation, LPS, and HR in BPAECs and ex vivo PAs. Survival of endothelial cells depends on ROS, NADPH oxidase, and PI3K and Akt. We postulate (Fig. 14) that 20-HETE activates PI3K and Akt first, which, in turn, activate NADPH oxidase to produce ROS. Based on our data, it is unclear which ROS product is critical to the prosurvival properties of 20-HETE, but it may be hydrogen peroxide, which has strong pro-proliferative properties (17). These functions suggest a potential role for CYP4 in regulating growth and survival of endothelial cells, which could have important physiological and pathophysiological implications in disorders such as pulmonary hypertension, recovery from a severe pneumonia, susceptibility to hypoxic lung injury, and others. Further studies to clarify the interaction of pro- and antisurvival signaling pathways triggered by 20-HETE, and the role of endogenous 20-HETE, are needed.

GRANTS

Financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health Grants HL49294 (E. R. Jacobs), HL68627 (E. R. Jacobs), HL069996 (M. Medhora), and GM 31278 (J. R. Falck) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (J. R. Falck).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rula Al-Saghir for performing the cell count and BrDU incorporations studies. This work would not be possible without technical assistance and equipment available in the Cardiovascular Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abid MR, Kachra Z, Spokes KC, Aird WC. NAPDH oxidase activity is required for endothelial cell proliferation and migration. FEBS Lett 486: 252–256, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaral SL, Maier KG, Schippers DN, Roman RJ, Greene AS. CYP4A metabolites of arachidonic acid and VEGF are mediators of skeletal muscle angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1528–H1535, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bain J, Plater R, Elliott M, Shapiro N, Hastie JP, McLauchlan H, Klevernic I, Arthur JSC, Alessi DR, Cohen P. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. Biochem J 408: 297–315, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brueckl C, Kaestle S, Kerem A, Habazettl H, Krombach F, Kuppe H, Kuebler WM. Hyperoxia-induced reactive oxygen species formation in pulmonary capillary endothelial cells in situ. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 34: 453–463, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Medhora MM, Falck JR, Pritchard KA, Jacobs ER. Mechanisms of activation of eNOS by 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid and VEGF in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L378–L385, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chowdhury AK, Watkins T, Parinandi NL, Saatian B, Kleinberg ME, Usatyuk PV, Natarajan V. Src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of p47phox in hyperoxia-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and generation of reactive oxygen species in lung endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 280: 20700–20711, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clerkina JS, Naughtona R, Quineya C, Cotter TG. Mechanisms of ROS modulated cell survival during carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett 266: 30–36, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhanasekaran A, Al-Saghir R, Lopez B, Zhu D, Gutterman DD, Jacobs ER, Medhora MM. Protective effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) on human endothelial cells from the pulmonary and coronary vasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H517–H531, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn KM, Renic M, Flasch AK, Harder DR, Falck JR, Roman RJ. Elevated production of 20-HETE in the cerebral vasculature contributes to severity of ischemic stroke and oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2455–H2465, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes Bertocchi AP, Campanhole G, Wang PH, Gonçalves GM, Damião MJ, Cenedeze MA, Beraldo FC, de Paula Antunes Teixeira V, Dos Reis MA, Mazzali M, Pacheco-Silva A, Câmara NO. A role for galectin-3 in renal tissue damage triggered by ischemia and reperfusion injury. Transpl Int 21: 999–1007, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebremedhin D, Lange AR, Lowry TF, Taheri MR, Birks EK, Hudetz AG, Narayanan J, Falck JR, Okamoto H, Roman RJ, Nithipatikom K, Campbell WB, Harder DR. Production of 20-HETE and its role in autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Circ Res 87: 60–65, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebremedhin D, Yamaura K, Harder DR. Role of 20-HETE in the hypoxia-induced activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channel currents in rat cerebral arterial muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H107–H120, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griendling KK, Sorescu D, Ushio-Fukai M. NADPH oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res 86: 494–501, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo AM, Arbab AS, Falck JR, Chen P, Edwards PA, Roman RJ, Scicli AG. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor through reactive oxygen species mediates 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-induced endothelial cell proliferation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321: 18–27, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo M, Roman RJ, Fenstermacher JD, Brown SL, Falck JR, Arbab AS, Edwards PA, Scicli AG. 9L gliosarcoma cell proliferation and tumor growth in rats are suppressed by N-hydroxy-N′-(4-butyl-2-methylphenol) formamidine (HET0016), a selective inhibitor of CYP4A. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 317: 97–108, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta A, Sharma S, Nain CK, Sharma BK, Ganguly NK. Reactive oxygen species-mediated tissue injury in experimental ascending pyelonephritis. Kidney Int 49: 26–33, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutterman DD Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species: an evolution in function. Circ Res 97: 302–304, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imig JD, Zou AP, Stec DE, Harder DR, Falck JR, Roman RJ. Formation and actions of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in rat renal arterioles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 270: R217–R227, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishizuka T, Cheng J, Singh H, Vitto MD, Manthati VL, Falck JR, Laniado-Schwartzman M. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid stimulates nuclear factor-kappaB activation and the production of inflammatory cytokines in human endothelial cells. Pharmacol Exp Ther 324: 103–110, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroetz DL, Xu F. Regulation and inhibition of arachidonic acid omega-hydroxylases and 20-HETE formation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 45: 413–438, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroetz DL, Zeldin DC. Cytochrome P450 pathways of arachidonic acid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol 13: 273–283, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunert MP, Roman RJ, Onso-Galicia M, Falck JR, Lombard JH. Cytochrome P-450 omega-hydroxylase: a potential O(2) sensor in rat arterioles and skeletal muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H1840–H1845, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medhora M, Daniels J, Mundey K, Fisslthaler B, Busse R, Jacobs ER, Harder DR. Epoxygenase-driven angiogenesis in human lung microvascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H215–H224, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medhora M, Chen Y, Gruenloh S, Harland D, Bodiga S, Zielonka J, Gebremedhin D, Gao Y, Falck JR, Anjaiah S, Jacobs ER. 20-HETE increases superoxide production and activates NAPDH oxidase in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L902–L911, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muthalif MM, Benter IF, Karzoun N, Fatima S, Harper J, Uddin MR, Malik KU. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid mediates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 12701–12706, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilakantan V, Maenpaa C, Jia G, Roman RJ, Park F. 20-HETE-mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis in ischemic kidney epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F562–F570, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ray R, Shaw AM. NADPH oxidase and endothelial cell function. Clin Sci 109: 217–226, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rey FE, Cifuentes ME, Kiarash A, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ. Novel competitive inhibitor of NAD(P)H oxidase assembly attenuates vascular O2− and systolic blood pressure in mice. Circ Res 89: 408–414, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roman RJ P-450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of cardiovascular function. Physiol Rev 82: 131–185, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang PS, Mura M, Seth R, Liu M. Acute lung injury and cell death: how many ways can cells die? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L632–L641, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ushio-Fukai M, Tang Y, Fukai T, Dikalov SI, Ma Y, Fujimoto M, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ, Johnson C, Alexander RW. Novel role of gp91(phox)-containing NAD(P)H oxidase in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling and angiogenesis. Circ Res 91: 1160–1167, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang JS, Singh H, Zhang F, Ishizuka T, Deng H, Kemp R, Wolin MS, Hintze TH, Abraham NG, Nasjletti A, Laniado-Schwartzman M. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in rats transduced with CYP4A2 adenovirus. Circ Res 98: 962–969, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang MH, Zhang F, Marji J, Zand BA, Nasjletti A, Laniado-Schwartzman M. CYP4A antisense oligonucleotide reduces mesenteric vascular reactivity and blood pressure in SHR. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280: R255–R261, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z, Tang X, Li Y, Leu C, Guo L, Zheng X, Zhu D. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid inhibits the apoptotic responses in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol 588: 9–17, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams JM, Sarkis A, Lopez B, Ryan RP, Flasch AK, Roman RJ. Elevations in renal interstitial hydrostatic pressure and 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid contribute to pressure natriuresis. Hypertension 49: 687–694, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasuda M, Ohzeki Y, Shimizu S, Naito S, Ohtsuru A, Yamamoto T, Kuroiwa Y. Stimulation of in vitro angiogenesis by hydrogen peroxide and the relation with ETS-1 in endothelial cells. Life Sci 64: 249–258, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Chatterjee S, Wei Z, Liu WD, Fisher AB. Rac and PI3 kinase mediate endothelial cell-reactive oxygen species generation during normoxic lung ischemia. Antioxid Redox Signal 10: 679–689, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu D, Zhang C, Medhora M, Jacobs ER. CYP4A mRNA, protein, and product in rat lungs: novel localization in vascular endothelium. J Appl Physiol 93: 330–337, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]