Summary

In clinical studies, longitudinal biomarkers are often used to monitor disease progression and failure time. Joint modeling of longitudinal and survival data has certain advantages and has emerged as an effective way to mutually enhance information. Typically, a parametric longitudinal model is assumed to facilitate the likelihood approach. However, the choice of a proper parametric model turns out to be more elusive than models for standard longitudinal studies in which no survival endpoint occurs. In this article, we propose a nonparametric multiplicative random effects model for the longitudinal process, which has many applications and leads to a flexible yet parsimonious nonparametric random effects model. A proportional hazards model is then used to link the biomarkers and event time. We use B-splines to represent the nonparametric longitudinal process, and select the number of knots and degrees based on a version of the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Unknown model parameters are estimated through maximizing the observed joint likelihood, which is iteratively maximized by the Monte Carlo Expectation Maximization (MCEM) algorithm. Due to the simplicity of the model structure, the proposed approach has good numerical stability and compares well with the competing parametric longitudinal approaches. The new approach is illustrated with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) data, aiming to capture nonlinear patterns of serum bilirubin time courses and their relationship with survival time of PBC patients.

Keywords: B-splines, EM algorithm, Functional data analysis, Missing data, Monte Carlo integration

1. Introduction

Often in medical studies both baseline and longitudinal covariates are collected for each subject, together with an event time of interest termed “survival time.” The goal is to model both the influence of covariates on survival time and the patterns of the longitudinal covariates. For instance, in AIDS studies the CD4 counts (a measure of immunologic and virologic status) of a patient are measured longitudinally and serve as biomarker for time-to-AIDS or time-to-death (Tsiatis, Degruttola, and Wulfsohn, 1995; Bycott and Taylor, 1998). Marginal approaches to separately model the longitudinal and survival components encounter diffculties when (a) the longitudinal measurements are scattered and contain measurement errors, or (b) the longitudinal process is not observable after the event time. Whereas (a) induces bias only to the survival components, (b) will cause biases to both components. A solution to overcome both problems is to combine the survival and longitudinal components and toestimate them simultaneously. We refer to the review article in Tsiatis and Davidian (2004) for details and simulation studies, which together with those in Henderson, Diggle, and Dobson (2000) demonstrated the advantage of joint modeling. This approach not only corrects the aforementioned bias problems, but also permits the submodels for the longitudinal and the survival parts to mutually gain information from each other.

For simplicity and without loss of generality, we assume that there is one time-independent (or baseline) covariate Zi, and one longitudinal covariate process (unobservable) Xi(t), for the ith subject, whose survival time is Ti. The event times Ti may be subject to the usual random censoring, and then only the minimum of survival and censoring time, Vi = min (Ti, Ci), and the censoring indicator, Δi = 1[Ti ≤ Ci], are observed. The longitudinal process is usually not fully observed, but rather is measured intermittently at times tij and with errors eij, which have zero mean and common variance . Hence the observed longitudinal data is

| (1) |

where mi is the number of longitudinal measurements for subject i.

For the survival component, the Cox proportional hazards model with baseline hazard function λ0 is commonly adopted, with hazard function for the ith subject given by

| (2) |

So far, the joint modeling approaches have primarily relied on parametric mixed effects models for the longitudinal processes Xi (t), where the unobserved random effects were treated as missing data and imputed by the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm. The computations can be quite intensive as multidimensional numerical integration is involved in the E-steps, and the computational cost surges as the number of random effects increases. The EM-algorithm may also become unstable and might not converge. Computational effciency thus often is the key to success for the joint modeling approaches. A parsimonious yet effective random effects model may provide a satisfactory solution and is the goal of this article.

Motivated by the primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) data in Section 5, we propose a simple yet flexible longitudinal model using only one random effect to link the population mean function μ(t) = E [Xi(t)] to the subject-specific profile through

| (3) |

Consequently, each subject has a profile proportional to μ(t), with the multiplicative factor bi describing the variation of each subject around the population mean. The unknown mean function μ(t) will be modeled and estimated nonparametrically through a set of basis functions in the nonparametric multiplicative random effects model (NMRE) given by (3).

Specifically, we approximate the mean function by B-spline basis functions Bl(·), 1 ≤ l ≤ L, (using boldface for column vectors)

| (4) |

The choice of the number of basis functions L will be discussed later. By allowing a suffcient number of B-spline functions we can approximate the overall mean function very well at little computational cost, as this involves estimating fixed effects. Meanwhile, we cut down the computational cost drastically as only one random effect is involved. A new estimating procedure for the mean function and variance components is described in Section 2. The proposed EM algorithm is very stable and converges quickly for the simulations in Section 3 and the data analysis in Section 4.

Note that our approach does not require any stationarity assumption and differs from the Bayesian approach in Brown, Ibrahim, and Degruttola (2005), where a more general nonparametric model is considered, but using the same number of random and fixed effects in an additive model. Their approach does not take advantage of the multiplicative structure of the longitudinal data that we propose. At first glance, the multiplicative random effects model (3) appears restrictive, but its applicability is much broader than anticipated. We note that longitudinal data are closely related to “functional data,” which are random functions on an interval I. A recent expository paper by Rice (2004) illuminates this by viewing longitudinal data as scattered realizations of functional data. The functional principal component (Karhunen—Loève) representation for X(t),

| (5) |

is based on the orthogonal eigenfunctions φk (t) of the covariance function G(s, t) = cov(Xi(s), Xi(t)). The Aik are uncorrelated random variables (known as the principal component scores) with mean 0 and variances λk, which are the eigenvalues of G(s, t) in descending order. Applying functional principal components analysis (Rice and Silverman, 1991; Ramsay and Silverman, 2005) for many data sets, we observed that often the first eigenfunction φ1(t) alone explains a large percentage (over 70%) of the variation of the data and has a similar shape as the mean function multiplied by a scale factor. This translates to φ1(t) = c μ(t) for some constant c, ignoring the remaining principal components Aik for k ≥ 2. Consequently, (5) is roughly equal to model (3) with bi =1 + cAi1. Data sets with this feature are plentiful and include the frequently studied AIDS data in the joint modeling literature and the PBC data in Section 4. Specific examples are (i) the AIDS data in Figures 1 and 4 of Yao, Müller, and Wang (2005), (ii) the hip cycle data shown in Figure 2 of Rice and Wu (2001), and (iii) the time course of14 C — folate in plasma of healthy adults (Yao et al., 2003). For these three data sets the first principal component explains, respectively, 76.9%, 71.2%, and 89% of the total variation, the mean functions mimic the corresponding first eigenfunctions, and the longitudinal trajectories from different subjects have different amplitude but similar overall shape, suggesting the appropriateness of the multiplicative random effects model (3) for these data.

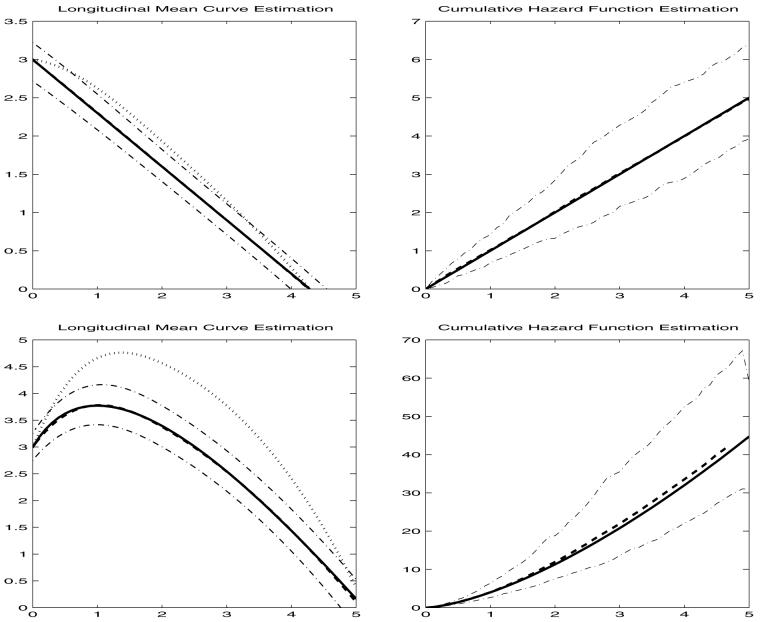

Figure 1.

Simulation results: estimated mean function (top: μ(t) = 3 - 0.7t, bottom: μ(t) = 4 log (t + 1) - 2t + 3) and cumulative hazard function with 95% Monte Carlo confidence intervals (dash-dot lines). The solid lines are the true function, dotted lines are the two-stage estimates, and the dashed lines are the estimates based on the procedure in Sections 2 and 3.

Figure 4.

Part (a) shows mean curve estimation and individual bilirubin profiles. Left panel is fitted longitudinal mean (dash line for NMRE and dotted line for TwoStage) with 95% bootstrap confidence interval (dash-dot lines) and mean of bootstrap estimation (solid line); right panel contains longitudinal bilirubin process for six randomly selected individuals (dots: observed bilirubin; crosses on x-axis: event time; diamonds on x-axis: censoring time; dashed lines: fitted longitudinal bilirubin; dash-dot lines: 95% prediction intervals). Part (b) shows the estimated baseline cumulative hazard (in the left panel) and smoothed hazard functions (in the right panel), with their 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (dash-dot lines).

Figure 2.

Individual longitudinal profiles: the true (solid line) and fitted (dashed line) profiles of eight randomly selected individuals from a random Monte Carlo sample. The observed longitudinal data are also plotted around the true curve, and the event time for each individual is marked on the x-axis with a cross indicating death and a diamond for censored observation.

To our knowledge, although more sophisticated random effect models have appeared in the literature, the simple random effect model in (3) has rarely been studied and certainly not in the joint modeling setting. We thus provide in the web-based supplementary material a simple algorithm to marginally estimate such longitudinal data as this could be of independent interest. The marginal estimates also serve as initial estimates for the EM algorithm in Section 2. The new approach is applied to the PBC data in Section 4, where about 17% of the subjects have no more than two longitudinal measurements and on the average five measurements per subject have been recorded. The measurement errors add further complications if one attempted to find a suitable parametric form for the trajectories of the longitudinal covariates. A nonpara-metric approach such as the multiplicative model in (3) is indeed worth exploring.

2. The Joint Likelihood Approach

Among the various approaches to jointly model survival and longitudinal data, the most promising one is perhaps the joint semiparametric likelihood approach, first proposed by Wulfsohn and Tsiatis (1997). We adopt such an effcient joint likelihood approach by assuming normal measurement errors eij, which are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) for all i and j. The random effects are independent of the measurement errors and are independent across subjects with some known distribution.

Let denote the vector of all unknown parameters defined in (1)–(4) and λ0(·) is a function of time, with the addition of θb to represent the parameter that determines the distribution of the random effects. Likewise, we denote the longitudinal covariate process Xi (t) as Xi (·). The vector notations, Xi = (X) i1,…,Ximi)T and W =(ii1,…,Wimi)T, denote, respectively, the unobserved covariates and observed measurements at the scheduled visits, where Xij = Xi(tij). With these notations the observed data for the ith subject are (Vi, Δi, Zi, Wi ), and i =1, …, n. Once the random effects bi are specified, the longitudinal and survival components are independent of each other, and the joint likelihood based on the observed data is easily found to be

| (6) |

where fb(bi ; θb) denotes the density function of the random effects and the other two density functions corresponding to the survival and longitudinal components are defined as follows:

| (7) |

Because the maximum of the likelihood in (6) is infinity if λ0 is completely unrestricted, we consider the nonparametric maximum likelihood (NPMLE) approach instead. Similar to the arguments in Johansen (1983) one can show that the NPMLE for λ0 is a point mass function with positive masses λk assigned to only those Vk whose Δk is equal to 1, where k = 1, …, D, with D being the total number of uncensored observations. We can thus parameterize it by λ0(·)= {λ1, …, λD and replace the baseline hazard function in (6) and (7) by this NPMLE. This results in a high-dimensional parameter whose dimension is of the same order as the sample size n. The likelihood in (6) involves unobserved random effects and integrations, so EM algorithm is typically employed to maximize it. However, the resulting EM algorithm might be unstable, due to the need of numerical integration in the E-step, especially if many random effects are included in the model. This numerical challenge is faced by all joint modeling approaches, but the simplicity of the proposed model (3) provides improvement and computational stability, as only one-dimensional numerical integration is involved for each covariate.

2.1 EM Algorithm

The likelihood for the complete data in the EM algorithm is simply the product . Below we describe the EM algorithm and use the superscript k in parentheses to indicate the position of the iteration, where all functions are evaluated at the current values of parameters. For example, is the conditional expectation of some function g, given the observed data of the ith subject and the estimate θ(k) at the kth iteration.

Step 0 (initialization): We propose a two-stage procedure, which does not require numerical integrations and is computationally fast, for the starting (k = 0) parameter estimates and . The first stage is to estimate the longitudinal parametric components and then the resulting random effects for all subjects. This allows us to impute the longitudinal process with the complete history for each subject. Details of the procedure are described in the supplementary material. In the second stage, we calculate a partial likelihood estimate for the survival regression parameters based on the imputed longitudinal process and then obtain the corresponding Breslow estimate for the baseline hazard function. This completes the two-stage procedure.

Step 1 (E-step): Due to the involvement of the survival density fsi, numerical integration is needed to evaluate the conditional expectations, , for several g-functions in the M-step based on the current estimate θ(k). We adopt the Monte Carlo method to generate a random sample, {b1i, … , bMi}, of size M for bi from the partial posterior density f(bi | Wi, θ(k) and approximate

The computational advantages of the simple multiplicative model are now evident, as the above Monte Carlo EM (MCEM) procedure involves only one random effect for each longitudinal covariate.

Step 2 (M-step): For the B-spline basis, let B(t) = (B1(t),…, BL(t))T be a column vector, and Bi = (B(ti1),…, B(timi)) be an L mi matrix. To indicate the at-risk status of the ith subject × at time t, we define Ri (t) = 1 if V i ≥ t, and Ri (t) = 0 otherwise. Direct maximization of the conditional expectation log-likelihood leads to closed-form estimates for and the point mass baseline function λ0(t), yielding updated estimates

| (8) |

| (9) |

where is the total number of longitudinal measurements for all subjects, and I is the indicator function. The prior parameter θb for the random effects may have a closed-form solution, such as for Gaussian random effects it is

Otherwise, it can be estimated similar to βZ, βX, and γ, all of which have no closed-form solution. To see this, define for h = 0, 1, and 2,

| (10) |

where U is a generic notation and will be replaced by b, Z, and X later. The profile score function for the coeffcients from the mean curve is

| (11) |

and the score functions for the regression coeffcients are

| (12) |

The score functions (11) and (12) are nonlinear functions of the current γ, βZ, and βX . Ideally, at each EM iteration we would solve these nonlinear systems together, which could be high dimensional especially if the number L of basis functions is large. However, the EM algorithm is already an iterative procedure, so it may not be necessary to accurately update these parameters at each M-step as long as the likelihood increases steadily during the iterations (Caffo, Jank, and Jones, 2005). We thus employ the one-step Newton—Raphson approach to get the updated λ(k+1), , and as in Henderson et al. (2000) and Wulfsohn and Tsiatis (1997). Simulation results in Section 4 confirm the satisfactory performance of this shortcut.

Step 3 (normalizing E(bi ) = 1): We set and normalize by dividing to ensure E(bi)=1 in model (3).

Step 4: Iterate among steps 1–3 until the algorithm numerically converges.

Remarks:

Conceptually, it is not necessary to normalize b̂i because the approach will automatically yield estimates close to this constraint. However, we have found that employing step 3 helps to improve the estimation of the mean function when the parameters are still biased during earlier iterations, especially at the beginning of the iteration.

We did not control the convergence criterion for λ0(.)in step 4 because it is not so crucial to accurately estimate λ0, as long as the cumulative baseline hazard function can be estimated precisely, which is often the case when all the other parameters have converged.

The choice of L for the number of basis functions is a model selection problem and will depend on the number of knots and the order of the B-spline functions. We used the Akaike information criterion (AIC) in the simulation and data application (Sections 5 and 6), based on the asymptotic optimality results of Shibata (1981), applicable when the number of basis functions in the true model is infinite or increases with the sample size, as is the case here.

The two-stage procedure in step 0 is simple and works well to generate the initial estimates. We propose two ways to estimate the random effects in the supplementary material. Tsiatis et al. (1995) had suggested a risk-set regression calibration approach to reduce the biases in the two-stage procedure when the longitudinal process is a linear mixed effects model. We could follow a similar scheme toreduce the biases in our multiplicative random effects model. However, it is not necessary to go through such an elaborated scheme just for the purpose of initial estimation.

There is some computational advantages to use normal random effects as the partial posterior density f(bi Wi, θ(k) needed to generate the Monte Carlo sample in the kth E-step would have a normal distribution. In non-Gaussian situations, this partial posterior density may not be trackable and Gibbs sampling may be needed to generate the Monte Carlo sample. This would induce additional computation cost. We note here that the joint likelihood approach is fairly robust against the assumption of normal random effects as observed in simulation studies in Song, Davidian, and Tsiatis (2002) and Tsiatis and Davidian (2004) and further explained from theoretical aspect in Hsieh, Tseng, and Wang (2006).

2.2 Variance Estimation

Variance estimation in joint modeling is an intriguing issue, as there is “missing information” involved in any EM algorithm. Louis (1982) suggested a correct variance formula, which essentially involves the calculation of the observed Fisher information matrix for the entire θ. However, this is a huge matrix in the joint modeling setting, due to the high dimensionality of the baseline hazard function. There is no shortcut to invert it in any joint modeling approach as explained in Hsieh et al. (2006). We thus revert to the bootstrap procedure to estimate the variance (or covariance) of θ. The exact bootstrap procedure (Efron, 1994) is similar to the one described in Section 3.5 of Tseng, Hsieh, and Wang (2005) and was employed to the PBC data. The resulting bootstrapped variance estimates seem quite reliable.

3. Simulation Study

Two simulations were performed: one has a linear longitudinal process with mean curve μ(t) = 3 – 0.7t and a simple constant baseline λ0(t) = 1, the other has a nonlinear longitudinal trajectory with μ(t) = 4log(t +1) 2t + 3 and a Weibull baseline function λ (t) = 6t1/2. In both settings, the random effects bi are normally distributed with mean 1 and variance 0.4. The measurement errors are first sampled from N(0, 0.25), independently of the random effects, but in the second nonlinear setting they are enlarged to have variance 0.4, to demonstrate the stability of our procedure when the signal-to-noise ratio is small. The censoring times are from exponential distributions. To mimic clinical studies, all subjects alive by the end of the study (time 5) are assumed to be censored. Overall, the censoring rates are 15.3% and 21.5% in the two settings. For each subject, 1–10 longitudinal measurements are randomly located in the time interval [0, 5], and these measurements are further truncated by Vi . On average, there are 4 and 3 longitudinal measurements per subject in the twosimulations, respectively. We use βX = -1 as the regression coeffcient for the survival component, and 100 Monte Carlo samples with sample size 200.

Table 1 presents the bias, Monte Carlo standard deviation (SD), and mean square error (MSE) for estimates of βX and the variance components in the longitudinal model. The PLME columns stand for the parametric linear mixed effects approach in Wulfsohn and Tsiatis (1997), which serves as benchmark, because this method utilizes the true parametric form of the longitudinal data. We report two types of two-stage (marginal) procedures. The first uses only longitudinal data before the observed event times Vi, and is designed to demonstrate the bias incurred by the informative dropout on the longitudinal data and the successful bias removal by the joint modeling approach. The second (adjacent in the table) uses all longitudinal data, including those beyond the event-times that are unobservable, so that the marginal approach in the web-based supplementary material should produce consistent estimates for the longitudinal component. The proposed joint modeling approach, which uses the first two-stage estimates as the initial estimates in the EM algorithm, is reported under the NMRE column. Our experience suggests that convergence of the PLME approach hinges upon a good choice of initial values, which should be selected with some care. The two-stage procedure worked well in our simulations and yielded less than 3% divergence rates for the PLME and none for our NMRE procedure. Moreover, the NMRE procedure performed well in terms of MSEs and nearly as well as the PLME. This is rather encouraging, as the NMRE utilizes no knowledge of the longitudinal mean shape. This excellent performance is probably due to the fact that the PLME involves two to three random effects, whereas NMRE involves only one and it demonstrates the computational accuracy gained by using fewer random effects. Moreover, the PLME approach could be grossly biased when the wrong parametric form was employed. We illustrate this in the second column (marked by a) of the PLME under the nonlinear simulation setting, in which the parametric longitudinal model is misspecified as being linear. In such a situation, the wrong PLME is associated with serious bias and inflated variance.

Table 1.

Simulation results: estimation of β and the variance components, in the two settings. Four methods are compared: joint likelihood based on parametric linear mixed effects (PLME) model, two types of two-stage procedures (Twostage) with/without informative dropouts, and the joint likelihood approach of Section 2 with nonparametric multiplicative random effects (NMRE) model.

| Linear longitudinal mean: μ(t) = 3 - 0.7t | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method |

β

|

|

|

|||||

| PLME | Twostage | NMRE | PLME | Twostage | NMRE | Twostage | NMRE | |

| Bias | -0.007 | 0.081/.019 | 0.006 | -0.004 | 0.190/.014 | -0.0004 | -0.124/-0.009 | 0.001 |

| SD | 0.110 | 0.098/.098 | 0.110 | 0.014 | 0.100/.063 | 0.014 | 0.043/.071 | 0.067 |

| MSE | 0.012 | 0.016/.010 | 0.012 | 0.0002 | 0.046/.004 | 0.0002 | 0.017/.005 | 0.004 |

| Nonlinear longitudinal mean: μ(t) = 4 log (t + 1) - 2t + 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method |

β

|

|

|

|||||

| PLME/a | Twostage | NMRE | PLME | Twostage | NMRE | Twostage | NMRE | |

| Bias | 0.0004/-0.202 | 0.122/.040 | -0.002 | -0.013 | 1.016/.002 | 0.0001 | -0.262/.023 | 0.008 |

| SD | 0.095/.176 | 0.104/.083 | 0.094 | 0.029 | 0.338/.063 | 0.029 | 0.030/.149 | 0.056 |

| MSE | 0.009/.072 | 0.026/.009 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 1.146/.004 | 0.001 | 0.069/.023 | 0.003 |

MisspecifiedPLME model with only slope andintercept.

As expected, marginal estimates from the informative missing longitudinal profiles have serious bias. The marginal approach using longitudinal measurements past event time leads to much smaller biases for β with almost no biases for the variance components. Its precision is comparable with that of the joint modeling approaches, indicating the feasibility of the proposed marginal approach (described in the web-based supplementary material) when there is no informative dropout involved in the study. Because this approach uses more longitudinal measurements per subject, but yields comparable MSEs as the NMRE, we have thereby also demonstrated the advantage of utilizing the survival information to improve the longitudinal estimation in the joint modeling approach.

In Figure 1, we present the nonparametric estimates of the longitudinal mean function (left panel) and the cumulative hazard function estimates (right panel) with their point-wise 95% confidence intervals, calculated from Monte Carlo quantiles. It is interesting tonote that, when the survival regression coeffcient βX is negative, the subjects with larger longitudinal measurements will have smaller risks and hence we observe more patients with lower risk or, equivalently, larger longitudinal measurements. This explains why the initial two-stage estimates are always noticeably biased upward. When βX is positive, the situation would be reversed, and this occurs for the PBC data in Section 4. Different knots choices were explored in the simulations and provided similar results, so only the cases with knot choices [0, 2, 5] and cubic splines are reported here. We also randomly selected eight individual trajectories and show the individual fitting results in Figure 2 under the nonlinear setting. The top left plot has a genuinely different shape compared to others (see the solid curve), and our estimate reflects such a variant shape well, as the fitted curve (dashed line) overlaps well with the true trajectory. The linear setting produced good fits too, which are not shown here to save space.

4. Analysis of PBC Data

We apply the proposed approach to the PBC data (Murtaugh et al., 1994) collected by the Mayo Clinic from 1974 to 1984. PBC is a chronic, fatal, but rare liver disease characterized by inflammatory destruction of the small bile ducts within the liver, which eventually leads to cirrhosis of the liver. Patients often present abnormalities in their blood tests, such as elevated and gradually increased serum bilirubin. Characterizing the patterns of time courses of bilirubin levels and their association with death due to PBC is of medical interest. In this randomized clinical trial, 158 out of 312 patients took the drug D-penicillamine, whereas the other patients were assigned to a control group. Some baseline covariates, such as age and gender, were recorded at the beginning of the study. Lab test results, such as serum bilirubin and albumin, were measured at the time of recruitment and at irregularly occurring follow-up visits, recorded until death or censoring. The observed event time ranges from 41 to 5225 days and 140 out of 312 patients had died by the end of study.

Fleming and Harrington (1991) studied the PBC data using only baseline covariates, and concluded that the drug D-penicillamine is not effective and five baseline covariates, including bilirubin, are significant. In our analysis, we take into account the subsequent longitudinal measurements during the follow-up period (Therneau and Grambsch, 2000). For simplicity, we only include the most significant biomarker, serum bilirubin, and one time-independent covariate, the treatment type. Model (2) will then allow us to (i) examine the treatment effect on survival after adjusting the longitudinal bilirubin levels, and (ii) check whether bilirubin still carries information on survival during the follow-up period after accounting for treatment assignment. If, however, we are interested to learn the effect of the treatment on bilirubin time courses itself and whether there is additional information in bilirubin on survival, after adjusting for any such potential treatment effect, we would need to modify both models (2) and (3) along the lines suggested in Aalen et al. (2004) and Fosen et al. (2006). Results not presented here indicate no treatment effects to bilirubin, so models (2) and (3) seem appropriate.

In a preprocessing step, we follow the clinical literature and take the logarithmic transformation of bilirubin. In the upper left panel of Figure 3, a three-dimensional plot shows all 312 bilirubin profiles, ordered by their event time Vi . Among them, 30 random samples are selected and shown in the upper right panel. Noticeably, the observed bilirubin data are noisy and vary a lot among patients, so it is not easy to pin down a suitable parametric model. We thus turn for the moment to the nonparametric functional principal component analysis approach described in Yao et al. (2005), which well accommodates sparse longitudinal data like these. The estimated mean function, μ(t), and the first eigenfunction, φ1(t), are shown in the lower panel of Figure 3 and referred as the “naive” mean function and eigenfunction estimates, because we have not dealt with the informative drop-outs yet. The first eigenfunction alone explained 79.6% of the variation and apart from scale has a similar shape as the naive mean function except in the right boundary region where the data are sparse and where both the mean and eigenfunctions are subject to heavier bias due to the informative drop-outs. This suggests that the proposed multiplicative random effects model (3) is suitable for the bilirubin data. The results are presented in Figure 4a and b, for four internal knots as selected by AIC and the quadratic B-spline basis. The resulting longitudinal plots are shown in Figure 4a with the 95% pointwise bootstrap confidence intervals based on 50 bootstrap samples. The fitted mean curve is nearly the same as the bootstrap mean curve, but the bias of the naive mean curve, replotted from Figure 3 is visually striking. The direction of the bias is as expected, because bilirubin is expected torise as the disease progresses, and patients with high bilirubin usually die earlier. The naive mean curve underestimates the seriousness of the disease.

Figure 3.

Upper left panel: 3D observed logarithm serum bilirubin ordered by event time for all patients; Upper right panel: the observed logarithm serum bilirubin trajectories for 30 randomly selected subjects, where the observed longitudinal measurements are denoted by dots; Lower left panel: the naive mean estimate for serum bilirubin; Lower right panel: the first functional principal component that explains 79.6% of the variation of the data. The mean curve and covariance smoothing bandwidth used for the lower panel figures are 1547 days and 1095 days, respectively, chosen by cross-validation in each procedure.

We also randomly select six subjects and plot their expected bilirubin trajectories together with 95% confidence bands in Figure 4a next to the mean curves. The top three plots are from the control group and the bottom three from the treatment group. The estimated cumulative hazard and baseline hazard functions are displayed in Figure 4b. For the baseline hazard estimate we use the kernel hazard estimates in Müller and Wang (1994), which employed Epanechnikov kernel with boundary adaption and local optimal bandwidth that minimizes the estimated local MSE. The baseline hazard function has a slight curvature but is not significantly different from a constant function. This matches the cumulative hazard function, which is very close to a linear function, and suggests that exponential distribution might be a good model for the baseline hazard function if one wishes to adopt a parametric approach for the survival data.

The parametric estimates for survival regression parameter and the variance components of the longitudinal data, as well as their bootstrap means and SDs, are presented in Table 2. The coeffcient estimated from the baseline bilirubin in Fleming and Harrington’s book is 0.8, significantly lower than 1.07, the estimate from NRME. This suggests that using only the baseline information on bilirubin may underestimate the risk for a patient. The estimate for the treatment coeffcient is with a bootstrap stand error of 0.17, indicating an insignificant drug effect. This is consistent with the findings in the literature based on baseline bilirubin levels. We thus conclude that D-penicillamine is ineffective to treat PBC, whether one controls for bilirubin levels or not. We also combined the treatment and control groups in a second analysis tosee how bilirubin relates tothe patient’s risk. The results were similar to those above and are not reported in detail.

Table 2.

NMRE results for PBC data

| βZ | βX | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | 0.07 | 1.07 | 0.20 | 1.72 |

| Bootstrap mean | 0.02 | 1.07 | 0.21 | 1.76 |

| Bootstrap SD | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

5. Conclusions and Discussion

We have presented a parsimonious nonparametric approach to fit the longitudinal profiles simultaneously with the survival data. Through expansions on B-splines and the joint modeling approach we recover the population- and subject-specific trajectories of the longitudinal covariates, and characterize the association between covariates and event time. The multiplicative random effects model is computationally attractive and allows us to incorporate multiple longitudinal covariates and time-independent covariates.

To check the applicability of the multiplicative assumption, one may plot the logarithm of the observed or presmoothed individual profiles to see whether they are parallel, when the longitudinal measurements are abundant per subject. In the case of sparse longitudinal data, the shape of individual profiles will be diffcult to detect and model checking may have to be carried out through some more elaborate scheme. For instance, one could follow the motivation provided in Section 1 to perform a functional principal component analysis (Yao et al., 2005) for the longitudinal component and then check whether (1) the first eigenfunction has a similar shape as the mean function, and (2) the first principal component explains a large proportion of the total variation. It is a judgement call to determine which fraction of variation is deemed sufficient to explain most of the variation of the longitudinal data. In our experience, we find the 70% threshold adequate, but the threshold will generally depend on the data. An unbiased functional principal component analysis in the joint modeling setting is currently being investigated. An ad hoc approach at this point would be to first carry out the Bayesian B-spline approaches in Brown et al. (2005) and derive from this a preliminary estimate of the covariance structure for the longitudinal data. Once we have a reliable covariance estimate, the approach in Yao et al. (2005) could be employed and will not lead to biases. Formal model diagnostics about the multiplicative model assumption can be done by including additional eigenfunctions (Chiou, Müller, and Wang, 2004) in the joint modeling setting and checking the adequacy of the first term.

We have discussed briefly in Section 4 how to add treatment effects to the multiplicative longitudinal model following the framework in Aalen et al. (2004) and Fosen et al. (2006). Other covariates can also be added to the longitudinal process by allowing the random effects to depend on the covariates. For instance, if there is only one covariate Z, the regression function under the multiplicative longitudinal model (3) would be E(X(t)|Z)=E(b|Z) μ(t), and one could model E(b|Z) either parametrically or | nonparametrically. When there are multiple covariates Z = (Zi, …, Zp), a fully nonparametric approach will not be practical and some dimension reduction approaches will be needed to model the covariate effects. One approach is to assume additive effects for each covariates, namely, with the functions gi unspecified. Another approach is to assume that a few indices summarize the information in all covariates, for instance, E(b|Z) = g (αT Z) for some unknown function g and p-dim vector α. Note that this would be parametric if g is a known function. None of the above approaches would affect the estimate for μ(t) because it is still the overall mean function.

We have allowed for negative bi and negative Xi (t) in the simulations and data analysis. This is because some subjects have negative values for their logarithm of bilirubin or their log (bilirubin) have an overall decreasing trend. The possibility of negative bi is also supported by the SD estimate of 1.31 in Table 2 as the mean is 1. In other applications, it may be impossible or undesirable to have negative bi . To impose such a constraint we could use truncated normal distribution for the random effects or other non-Gaussian distribution, such as lognormal, Weilbull, and Gamma, on the random effects.

Theoretical arguments on the legitimacy of AIC in the joint modeling setting are not available yet and are worth pursuing. Other model selection procedures, such as BIC, HQ, and cross-validation (or generalized cross-validation) could be employed as well, but they would all be ad hoc at this point, as there are no theoretical justifications available for any model selection procedure under the joint modeling setting. Obviously, there is much work to be done, including model diagnostics and formal inference procedures based on theoretical advances.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research of Jane-Ling Wang was supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation (DMS04-06430). The authors wish to thank the reviewers, especially the associate editor, for insightful suggestions, which led to a much improved version of the article.

Footnotes

6. Supplementary Material

Web Appendixes referenced in Sections 1, 2.1, and 3 are available under the Paper Information link at the Biometrics web-site http://www.biometrics.tibs.org.

References

- Aalan OO, Fosen J, Weedon-Fekjær H, Borgan Ø, Husebye E. Dynamic analysis of multivariate failure time data. Biometrics. 2004;60:764–773. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ER, Ibrahim JG, Degruttola V. A flexible {B-spline} model for multiple longitudinal biomarkers and survival. Biometrics. 2005;61:64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2005.030929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bycott P, Taylor J. A comparison of smoothing techniques for CD4 data measured with error in a time-dependent Cox proportional hazards model. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:2061–2077. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980930)17:18<2061::aid-sim896>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffo BS, Jank W, Jones G. Ascent-based Monte Carlo expectation-maximization. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 2005;67:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou JM, Müller HG, Wang JL. Functional response models. Statistica Sinica. 2004;14:675–693. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Missing data, imputation and bootstrap (with discussion) Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1994;89:463–479. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming TR, Harrington DP. Counting Process and Survival Analysis. Wiley; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fosen J, Borgan Ø , Weedon-Fekjær H, Aalan OO. Dynamic analysis of recurrent event data using the additive hazard model. Biometrical Journal. 2006;48:381–398. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200510217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R, Diggle P, Dobson A. Joint modelling of longitudinal measurements and event time data. Biostatistics. 2000;4:465–480. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh F, Tseng YK, Wang JL. Joint modelling of survival and longitudinal data likelihood approach revisited. Biometrics. 2006;62:1037–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen S. An extension of Cox’s regression model. International Statistics Review. 1983;51:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Louis TA. Finding the observed information matrix when using the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1982;44:226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Müller HG, Wang JL. Hazard rate estimation under random censoring with varying kernels and bandwidths. Biometrics. 1994;50:61–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaugh PA, Dickson ER, Van Dam GM, Malincho M, Grambsch PM, Langworthy AL, Gips CH. Primary biliary cirrhosis: Prediction of short-term survival based on repeated patient visits. Hepatology. 1994;20:126–134. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice J. Functional and longitudinal data analysis: Perspectives on smoothing. Statistica Sinica. 2004;14:631–647. [Google Scholar]

- Rice J, Silverman B. Estimating the mean and covariance structure nonparametrically when the data are curves. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1991;53:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Rice J, Wu C. Nonparametric mixed effects models for unequally sampled noisy curves. Biometrics. 2001;57:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay J, Silverman B. Functional Data Analysis. 2nd Springer; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata R. An optimal selection of regression variables. Biometrika. 1981;68:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Davidian M, Tsiatis AA. A semi-parametric likelihood approach to joint modelling of longitudinal and time-to-event data. Biometrics. 2002;58:742–753. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Springer; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng YK, Hsieh F, Wang JL. Joint modelling of accelerated failure time and longitudinal data. Biometrika. 2005;92:587–603. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiatis AA, Davidian M. Joint modelling of longitudinal and time-to-event data: An overview. Statistica Sinica. 2004;14:809–834. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiatis AA, Degruttola V, Wulfsohn MS. Modelling the relationship of survival to longitudinal data measured with error. Applications to survival and CD4 counts in patients with AIDS. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wulfsohn MS, Tsiatis AA. A joint model for survival and longitudinal data measured with error. Biometrics. 1997;53:330–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao F, Müller HG, Clifford AJ, Dueker SR, Follett J, Lin Y, Buchholz BA, Vogel JS. Shrinkage estimation for functional principle component scores with application to the population kinetics of plasma folate. Biometrics. 2003;59:676–685. doi: 10.1111/1541-0420.00078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao F, Müller HG, Wang JL. Functional data analysis for sparse longitudinal analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2005;100:577–590. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.