Abstract

Our previous work showed a diminished cerebral blood flow (CBF) response to changes in PaCO2 in congestive heart failure patients with central sleep apnea compared with those without apnea. Since the regulation of CBF serves to minimize oscillations in H+ and Pco2 at the site of the central chemoreceptors, it may play an important role in maintaining breathing stability. We hypothesized that an attenuated cerebrovascular reactivity to changes in PaCO2 would narrow the difference between the eupneic PaCO2 and the apneic threshold PaCO2 (ΔPaCO2), known as the CO2 reserve, thereby making the subjects more susceptible to apnea. Accordingly, in seven normal subjects, we used indomethacin (Indo; 100 mg by mouth) sufficient to reduce the CBF response to CO2 by ∼25% below control. The CO2 reserve was estimated during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. The apnea threshold was determined, both with and without Indo, in NREM sleep, in a random order using a ventilator in pressure support mode to gradually reduce PaCO2 until apnea occurred. results: Indo significantly reduced the CO2 reserve required to produce apnea from 6.3 ± 0.5 to 4.4 ± 0.7 mmHg (P = 0.01) and increased the slope of the ventilation decrease in response to hypocapnic inhibition below eupnea (control vs. Indo: 1.06 ± 0.10 vs. 1.61 ± 0.27 l·min−1·mmHg−1, P < 0.05). We conclude that reductions in the normal cerebral vascular response to hypocapnia will increase the susceptibility to apneas and breathing instability during sleep.

Keywords: PaCO2, apnea

impaired cerebrovascular response to CO2 and attenuated cerebral perfusion have been observed in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) (6, 18, 27, 35). This group of patients also suffers a high prevalence of periodic breathing (22, 39). Our previous studies further showed that patients with central sleep apnea (CSA) have two major pathologic features compared with those with similar cardiac function but no periodic breathing. One is a lower cerebrovascular reactivity to CO2 (51) and the other is a smaller CO2 reserve [ΔPaCO2 (eupnea PaCO2 − apneic threshold PaCO2)], which reflects an enhanced disposition toward apnea and breathing instability (3, 50). These correlative findings suggest a possible cerebrovascular mechanism for sleep-related periodic breathing, at least in patients with CHF.

The possibility that alterations in cerebral blood flow (CBF) regulation could cause breathing instability is based on highly sensitive control of the cerebral vasculature via changes in PaCO2 and the inverse relationship between CBF and ventilation (7, 8, 16, 32). The central chemoreceptors are stimulated as the result of constriction of the cerebral vessels and, conversely, depressed by dilatation of these vessels (16, 38). This relationship exists because a decrease in CBF will impede the removal of the respiratory stimulant, CO2, from the medulla, while an increase in CBF will facilitate CO2 removal. Furthermore, the cerebral vasculature responds very quickly to changes in PaCO2; therefore subsequent changes in CBF provide an ongoing regulation of ventilation on a second by second basis (38). This influence becomes more important during sleep as PaCO2 becomes the critical factor in maintaining rhythmic breathing when the wakefulness stimulus is absent (4, 40). Thus reduction of such vasomotor reactivity renders ventilation vulnerable to relatively small transient changes in PaCO2, easily provoking apnea and periodic breathing.

In a previous study we assessed the role of CBF in ventilatory control by reducing CBF and the cerebrovascular response to CO2 via indomethacin (Indo) in 9 normal awake human subjects. Indo increased eupneic ventilation and reduced PetCO2 and caused a significant increase in the ventilatory response to hypercapnia (52). In turn, it has been suggested that an exaggerated central chemoreceptor CO2 responsiveness might lead to feedback instability in the chemoreflex, thereby becoming a major contributor to periodic breathing (25). We therefore hypothesized that a reduction in the CBF response to CO2 would increase the susceptibility to apnea during sleep, which would be reflected in a smaller CO2 reserve. Accordingly, we used oral Indo to reduce CBF and the cerebrovascular responsiveness to CO2 in healthy subjects and determined the effect on the ventilatory response to transient reductions in PaCO2 below eupnea during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.

METHODS

Subjects.

Seven normal subjects (5 men, 2 women, aged 18–35 yr; body mass index of 23 ± 2) participated in two-night experiments with/without an oral administration of Indo. Female volunteers were studied in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. All were non-smokers, non-obese, non-snoring, normotensive, and free from cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neurological diseases. Subjects were asked to abstain from caffeine and alcohol for their supper and to arrive at the laboratories 2 h prior to their normal bedtime. To facilitate sleep and to depress arousal, 10 mg of zolpidem, which did not show any effect on CBF perfusion in normal baboons (9), were given orally to all subjects prior to lights out. This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Human Subjects Committee.

Polysomnographic methods.

Sleep studies were performed at night on each subject under control and Indo conditions. Standard polysomnographic techniques were used to identify sleep stages and arousals (36). Ventilation was measured using a pneumotachograph (#5719; Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO) that was attached to a leak-free nasal mask. The airway pressure was measured with a pressure transducer, connected to a port in the mask. Respiratory effort was monitored using respiratory inductive plethysmography (Respitrace, Ambulatory Monitoring), which was calibrated with an isovolume maneuver and then secured by dressing tape. SaO2 was measured continuously by a pulse oximeter (Biox #3740; Ohmeda, Madison, WI). End-tidal PCO2 (PetCO2) and PO2 (PetO2) were sampled from the nasal mask and measured by a gas analyzer (AMETEK, model CD-3A). All variables were recorded continuously on a polygraph (model 78D; Grass Instruments) and simultaneously on a computer for later analysis.

Indo and CBF.

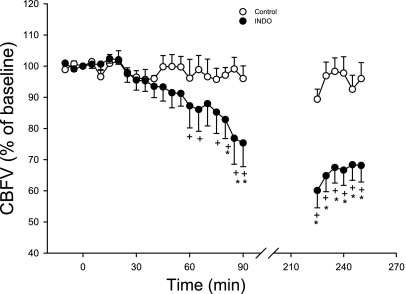

The subjects took either 100 mg of Indo with 20 ml Maalox (treatment) or 20 ml Maalox alone (control) before lying down on the bed. We previously determined the effects of this dose of oral Indo on middle cerebral artery blood velocity (CBFV) in nine subjects, including the same seven subjects as enrolled in the current study, using the transcranial Doppler technique (52). However, we were unable to monitor CBF during sleep in this present study owing to technical problems with maintaining the position of the Doppler probe (Marc 600, Spencer Technologies). Therefore we used those previously obtained data to show the effects of Indo on CBFV for the seven current subjects during wakefulness. Note that CBFV began to decrease ∼30 min following Indo ingestion, fell to 75 ± 8% of control by 90 min postingestion, and remained at 68 ± 5% of control by 4 h postingestion (Fig. 1). The cerebrovascular response to hypocapnia (ΔCBFV/ΔPetCO2) was depressed by two-thirds at 2–3 h post-Indo ingestion (52). Given these data we assumed that CBFV would be reduced and the cerebrovascular response to CO2 would be significantly attenuated up to 4 h following Indo ingestion and during the period the subjects were studied in NREM sleep (also see discussion for justification).

Fig. 1.

Effect of 100 mg oral dose of indomethacin (Indo) on resting cerebral blood flow velocity (CBVF) over 4 h in the 7 subjects during wakefulness. By 90 and 250 min after Indo ingestion, the CBFV decreased to 75 ± 8% and 68 ± 5%, respectively, of the initial value, which was significantly lower than the control value at the same time point. This figure represents a portion of the data obtained in a previous related study (52), which included the 7 subjects used in the present study (see methods).

Measurement of the CO2 reserve.

A mechanical ventilator (Hamilton Medical, Veolar) was attached to each subject through a sealed nasal mask. The mouth was taped shut to prevent air leaks. The inspiratory and expiratory tidal volumes were monitored to detect leaks of respiratory system. The ventilator was set in the pressure support mode, which allowed for an independent adjustment of the inspiratory and end-expiratory pressures. All subjects were initially kept on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at 2–4 cmH2O to minimize the upper airway resistance. The trigger sensitivity of the ventilator was set to 2 cmH2O below the CPAP level.

During stable stage II-III NREM sleep, after 90 min of either Indo (Indo + Maalox) or placebo (Maalox alone) ingestion, we started a 3-min baseline of cardiorespiratory measurements. Following the baseline measurements, multiple trials of hyperventilation were performed as previously described (50). For the first trial, the pressure support was progressively increased to find the minimum pressure required to produce an apnea. The initial pressure support level was 4 cmH2O above CPAP. If no apnea or hypopnea occurred after 1 min, the inspiratory pressure was increased in 2 cmH2O increments at 1-min intervals, with the end-expiratory pressure remaining unchanged, until apneas and/or hypopneas occurred. For the subsequent trials, the pressure support was increased directly from zero to the approximate target level required to trigger an apnea. At least 3–5 min of spontaneous breathing were given between each trial to allow the ventilation and PaCO2 to return to their baseline levels.

This same protocol was performed on two separate nights with a random order of Indo vs. control. It turned out that three of the seven subjects received Indo on their first night. For the female subjects, the two experiments were conducted no longer than 3 days apart to ensure a similar phase of their menstrual cycles. At least three apneic threshold determinations were performed on each subject during NREM sleep to ensure reproducibility.

Data analysis.

Sleep stages and arousal were scored according to standard criteria (50). Respiratory parameters including tidal volume (Vt), frequency (f), minute ventilation (V̇e), and PetCO2 were measured breath-by-breath. The baseline values were determined by averaging all breaths during stable, spontaneous breathing on CPAP and were compared between the two nights with and without Indo. Central apnea was defined as an absence of airflow/mask pressure and perceptible inspiratory effort on the Respitrace for a length of at least 10 s. Hypopnea was defined as two or more untriggered efforts detected on the mask pressure tracing associated with a 50% or greater reduction in Vt. The apnea and hypopnea thresholds were determined by averaging PetCO2 of the three successive breaths immediately prior to either the first apnea or first hypopnea. The proximity of apneic/hypopneic threshold for PetCO2 to eupneic PetCO2 was calculated by subtracting the apneic/hyponeic threshold PetCO2 from the baseline PetCO2; while the ventilatory response to CO2 below eupnoea was calculated by dividing the ΔV̇e (eupneic V̇e − apneic V̇e) by the ΔPetCO2. Data were collected only during stable NREM sleep, and trials that resulted in awakening or arousal were excluded from analysis. The data are presented as the group mean ± SE, which was an average of each subject's mean, and the individual mean value was calculated from five to eight trials. Statistical comparisons between the two nights were performed by using paired t-test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

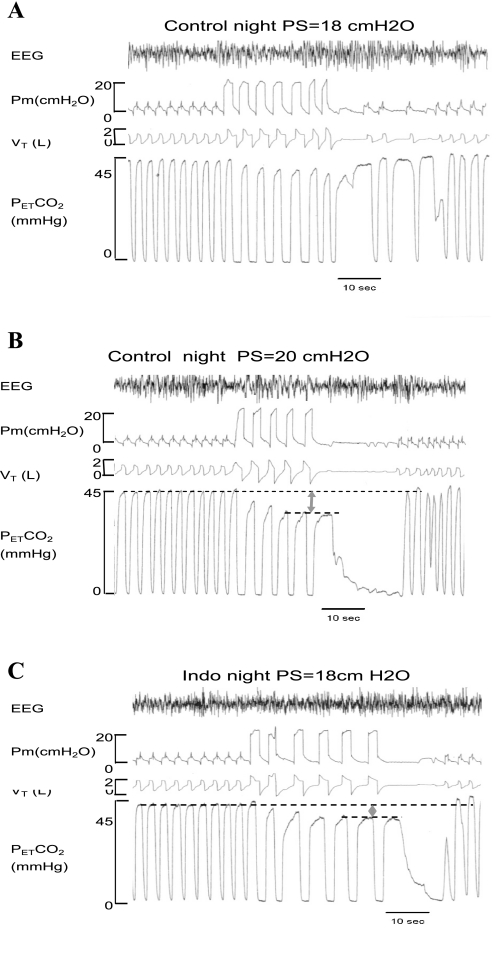

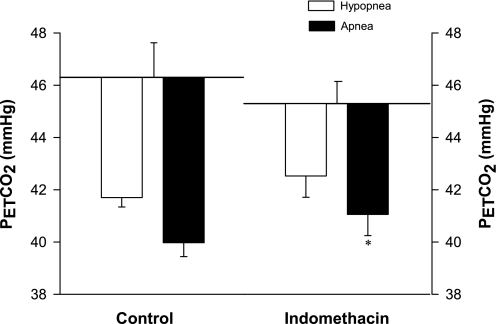

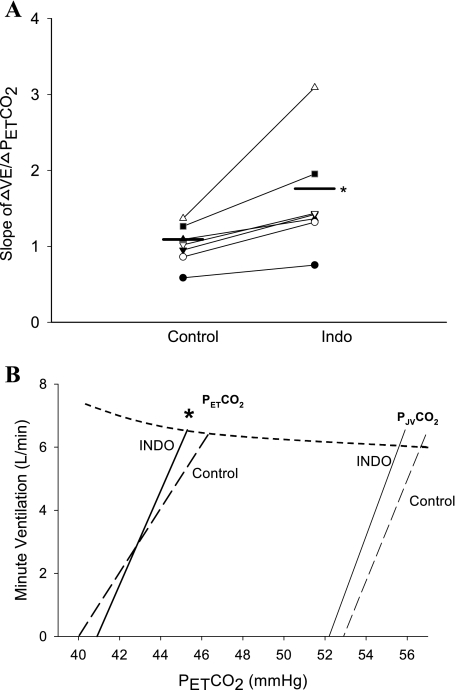

Indo caused a consistent narrowing of CO2 reserve [ΔPetCO2 (eupnea PetCO2 − apnea threshold)] during NREM sleep (range −0.5 to −4.2 mmHg) in all subjects (Figs. 2–3), with the mean value being reduced from 6.3 ± 0.5 to 4.4 ± 0.7 mmHg (P = 0.01). The smaller CO2 reserve with Indo consisted of a relatively consistent (in 5 of 7 subjects) but statistically insignificant reduction of baseline PetCO2 (control vs. Indo: 46.3 ± 0.9 vs. 45.3 ± 1.3 mmHg, P = 0.39), combined with small increase in the apneic threshold (40.0 ± 0.9 vs. 40.9 ± 1.0 mmHg, P = 0.32) (Fig. 3). In turn, the narrowed CO2 reserve was due to a steeper slope in ventilatory response to hypocapnic disfacilitation (control vs. Indo: 1.06 ± 0.10 vs. 1.61 ± 0.27 l·min−1·mmHg−1, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4). The apnea lengths obtained at the apnea threshold PetCO2 were comparable following the placebo and Indo administrations (27.2 ± 2.0 vs. 25.0 ± 2.7 s, P = 0.24). In addition, the proximity of eupnic PetCO2 to the hypopnea threshold PetCO2 was reduced in five of seven subjects (range +2 to −5) with the group mean not quite reaching statistically significant at P < 0.05 (control vs. Indo: 4.7 ± 0.4 mmHg to 2.6 ± 0.9 mmHg, P = 0.08) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

One representative subject's polygraph records for 2 nights of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. In the control night (A and B), a reduction of PetCO2 by 7.3 mmHg at a pressure support of 20 cmH2O was required to cause a central apnea. In the Indo night (C), central apnea occurred at a lower level of pressure support (18 cmH2O) and with less reduction of PetCO2 (−5.2 mmHg). This same level of pressure support with the same reduction of PetCO2 caused only an hypopnea with no apnea in the control night (A).

Fig. 3.

Group data for ΔPetCO2 (eupnea − apnea) and ΔPetCO2 (eupnea − hypopnea). Indo resulted in a significant reduction of the CO2 reserve [ΔPetCO2 (eupnea − apnea] from 6.3 ± 0.5 control to 4.4 ± 0.7 mmHg, P = 0.01) and a relatively smaller ΔPetCO2 (eupnea − hypopnea) (2.6 ± 0.9 vs. 4.7 ± 0.4 mmHg, P = 0.08). **P < 0.01.

Fig. 4.

A: influence of Indo on the ventilatory response to hypocapnia inhibition below eupnea. Indo caused an increase in the slope of ΔV̇e/ΔPetCO2 (control vs. Indo: 1.06 ± 0.10 vs. 1.61 ± 0.27 l·min−1·mmHg−1, P < 0.05). B: group mean ventilatory responses to reductions in PetCO2 and to estimated jugular venous Pco2 below the eupneic Pco2. The dashed curve represents a theoretical metabolic hyperbola at V̇co2 = 250 ml/min. Each line was drawn between the point of eupneic ventilation at its eupneic Pco2 and the Pco2 at the apneic threshold. Jugular venous Pco2 was estimated using the formula PJVco2 = PetCO2 + 10.6 − (y − 100) × 0.07, derived from the work of Fencl (17), which showed that a reduction in cerebral blood flow (CBF) of 1% caused average increase of 0.07 mmHg in jugular venous Pco2. The slope of the ΔV̇e/ΔPetCO2 below eupnea was increased significantly via Indo (also see A); whereas the slope of the ΔV̇e/ΔPJVco2 was unchanged. Therefore, the increased ΔV̇e/ΔPetCO2 with Indo was likely attributable to a compromised capability to widen the arterial to jugular venous Pco2 difference (also see results). *P < 0.05.

Within-subject trial to trial variability is shown in Table 1. Five to eight multiple level pressure support ventilator trials per subject were performed in NREM sleep. The coefficient of variation of the apneic threshold value averaged 3.6 to 4.2%; and for the hypopneic threshold, the coefficient of variation averaged 4.3 to 5.2%.

Table 1.

Trail to trail variability for apnea and hypopnea threshold measurements

| Control Night |

Indo Night | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apnea | Hypopnea | Apnea | Hypopnea | |

| # of trials | 6.9±0.9 | 7.4±0.8 | 5.7±1.0 | 7.4±1.4 |

| CV | 3.6%±0.6% | 5.2%±0.8% | 4.2%±0.8% | 4.3%±0.7% |

Values are means ± SE. Ιndo, indomethacin; CV, coefficient of variance.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that Indo increases the ventilatory response slope to acute reductions in PaCO2 during NREM sleep and narrows the difference between the eupneic PetCO2 and the apnea threshold PetCO2 (i.e., CO2 reserve). The CO2 reserve is a sensitive index of the propensity for apneas that occur during sleep in response to transient ventilatory overshoots (13), and a narrowed CO2 reserve may predispose subjects to periodic breathing (31, 51). Hence, this observation points to a possible CBF-related mechanism contributing to sleep-related breathing instability.

Methodological considerations.

We used Indo as a pharmacological tool to manipulate CBF (see Fig. 1). Indo is absorbed promptly and extensively from the gastrointestinal tract, with an onset of action of ∼30 min and duration of action of about 4–6 h (10, 26). This time frame accords with our observations in our daytime study (52), and it is sufficient for us to complete our nighttime sleep measurements of the apneaic threshold. Our ongoing studies have shown that Indo was able to reduce CBFV similarly during sleep and wakefulness (37, 54).

Although we and others have shown that Indo administration attenuates the cerebrovascular sensitivity to both hypercapnia and hypocapnia (12, 15, 28, 45, 48, 52), several factors need to be clarified before we can attribute the Indo-induced ventilation alteration to the Indo-induced changes in CBF. First, Indo may affect breathing through its inhibitory influence on prostaglandins. However, as we discussed in our previous paper (52), the direct effect of prostaglandin inhibition per se on ventilation is negligible (4, 26).

A second consideration is that Indo may affect breathing through other mechanisms outside the brain and central chemoreceptors, such as at the level of the carotid body chemoreceptors. Gómez-Niño et al. (19, 20) found in in vitro preparations that Indo enhanced the carotid body sensitivity to hypoxia and hypercapnia stimulation, although Indo had no effect on the carotid body output under normoxic, eucapnic conditions. On the other hand, limited in vivo studies suggest that the excitatory effect of Indo on breathing does not involve peripheral chemoreceptors. For example, Jansen et al. (23) reported that chronic denervation of the carotid sinus and aortic bodies in fetal lambs did not modify Indo-induced activation of breathing movements. Wolsink et al. (49) investigated the influence of Indo on the ventilatory response to normoxic CO2 in anesthetized piglets by using the dynamic end-tidal forcing technique. They found that Indo only increased the CO2 sensitivity of the (slow) central component of the CO2 response without affecting the (fast) peripheral CO2 sensitivity in these piglets. In addition, a study in anesthetized cats showed that prostaglandins themselves may not activate carotid chemoreceptors, as prostaglandin infusion caused a greater increase in V̇e after bilateral section of carotid sinus nerves (30), which excludes the possibility that Indo might affect the carotid bodies by inhibiting prostaglandins. Finally, the involvement of the peripheral chemoreceptors in the ventilatory response to Indo in humans seems unlikely because our previous experiments showed similar influences of Indo on enhancing the ventilatory response to both normoxic and hyperoxic hypercapnia (52). Similarly, our ongoing human studies showed that Indo-associated hyperventilation under normoxic conditions was not reduced when the carotid bodies were suppressed by background hyperoxia (unpublished data).

A dosage of Indo that was 3.7 times that used in our study may attenuate the lung volume response to positive pressure (2, 14), i.e., higher positive pressure was required to reduce PaCO2 by a given amount. However, our study showed that apnea occurred at a lower level of pressure support with less reduction in PetCO2 in the Indo night compared with the control night (Fig. 2). Perhaps the dose of Indo we used in our experiment was not high enough to significantly affect lung mechanics.

Mechanisms for narrowing of the CO2 reserve with reduction of cerebrovascular response to CO2.

We previously demonstrated that Indo increased the slope of V̇e response to the addition of CO2 above eupnea in awake subjects (52); while in the present study we observed that Indo increases the slope of V̇e inhibition to withdrawal of CO2 below eupnea in sleep. Together, our results suggest a parallel influence of cerebrovascular responsivity to CO2 on ventilation above and below eupnea, which in turn would contribute to augmentation of both ventilatory overshoots and undershoots, i.e., instability during sleep.

How did Indo affect brain Pco2 in eupnea and during transient hypocapnia? Indo decreases resting CBF and attenuates the cerebrovascular sensitivity to CO2 (3, 15, 28, 45, 52), and we recently showed that this effect is also present during NREM sleep (54). The Indo-induced reduction in resting CBF leads to an accumulation of CO2 and H+ in brain, which stimulates ventilation, thereby reducing eupneic PetCO2 and reducing the plant gain. On the other hand, the Indo-induced attenuation of CBF response to change in CO2 increases the controller gain (slope of ΔV̇e/ΔPco2) (also see below). For example, in our experiments, the transient reduction in PaCO2 normally causes a cerebrovascular constriction, thereby reducing the washout of CO2, increasing the arterial to CSF Pco2 difference, and preserving brain Pco2 and H+. As this protective cerebral vascular constriction was impaired by Indo, brain Pco2 and H+ would be washed out in a noncontrolled manner when PaCO2 is falling, sensitizing the ventilatory depression to hypocapnia and significantly increasing the slope of ventilatory response below eupnea. Although the increased controller gain would be offset in part by the reduced plant gain, the net effect was a reduced CO2 reserve and, therefore, increased susceptibility for apnea and periodicity. We previously reported similar types of opposing effects of hypoxia on plant vs. controller gains in sleep (31, 50), although the net effect on narrowing the CO2 reserve was substantially greater than with Indo.

Our estimates of the quantitative effects of a compromised cerebrovascular responsiveness on brain Pco2 provides a basis for explaining the increased slope of the ventilatory response to CO2 below eupnea (see Fig. 4). For example, if we apply our previous findings showing that Indo decreased the CBF responsiveness to CO2 to one-third below control (52) to the data of Fencl (16), we estimate that in control, jugular venous Pco2 (PJVco2) was reduced by 4 mmHg at the apnea threshold, requiring a reduction of 6.3 mmHg in arterial Pco2. When cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypocapnia was blunted with Indo, only a 4.4 mmHg reduction in arterial Pco2 was required to reach the apnea threshold but at about the same reduction in PJVco2 (3.7 mmHg) as under control conditions. Accordingly, as shown in Fig. 4, the slope of the ΔV̇e/ΔPetCO2 below eupnea was increased significantly via Indo; whereas the estimated slope of the ΔV̇e/ΔPJVco2 was unchanged. This means that alteration in CBF changes the ventilation response slope to reduced arterial Pco2 through only modifying the chemical environment of central chemoreceptors with no alteration in central chemosensitivity per se. Thus the increased ΔV̇e/ΔPetCO2 was likely attributable to a compromised capability to widen the arterial to jugular venous Pco2 difference in response to hypocapnia. Even these relatively small effects on Pco2 in the environment of the central chemoreceptors are likely to be important to ventilatory control during sleep when a tonic CO2 input becomes critical for breathing rhythmicity due to the withdrawal of the wakefulness stimulus (4, 40).

Central or peripheral chemoreception or both?

Cerebral blood flow affects the environment of the central chemoreceptors. However, the apnea that commonly follows a transient ventilatory overshoot in NREM sleep appears to depend critically on hypocapnia being sensed by the peripheral chemoreceptors (31, 42, 43, 53). How then did Indo cause a narrowed CO2 reserve?

We speculate that this effect of Indo is most likely attributed at least in part to an interdependence of central chemoresponsiveness on peripheral chemoreceptor stimulation and vice versa. Takakura et al. (46) recently showed in anesthetized rats that CO2-sensitive neurons in the retrotrapezoid nucleus responded to systemic hypoxia or cyanide, and this central response was prevented via carotid body denervation. Further, Day and Wilson (11) reported in decerebrate rats with isolated perfusion of the medulla that the level of central CO2 significantly influenced the respiratory motor response to systemic hypercapnia. Perhaps then an exaggerated brain hypocapnia would augment the peripheral chemoreceptor sensitivity to transient hypocapnia. Thus far this proposed peripheral and central chemoreceptor interdependence has not been demonstrated in humans, in whom transient time-dependent ventilatory responses to hypoxia and CO2 were employed in attempts to estimate the contributions from each set of chemoreceptors (44). These findings in human studies claiming no chemoreceptor interaction are very difficult to interpret because of the unknown and unsubstantiated potentiating after effects on ventilatory drive that must occur on withdrawal of the peripheral or central stimulus, but cannot be singled out in these studies because of the lack of chemoreceptor separation.

As a reasonable possibility we should also consider that the predominant role for peripheral vs. central chemoreceptors in causing apnea may be explained in part because hypocapnia-induced cerebrovascular constriction partially preserves Pco2 and [H+] at the central chemoreceptors, thereby protecting the latter from being exposed to a lower brain Pco2. Accordingly, when cerebrovascular reactivity to hypocapnia was attenuated, as with Indo, the brain blood flow underwent a smaller reduction with transient hypocapnia, allowing CO2 to wash out in an uncontrolled manner, consequently destabilizing breathing during sleep.

In summary, we need to emphasize that the relative contributions of central vs. peripheral chemoreceptors are difficult to distinguish under these complex conditions of transient, fast alterations in the CO2 and pH of the respective environments of both sets of receptors. We favor an explanation of a peripheral-central interaction to explain both the apparent highly sensitive apneic threshold mediated by the carotid chemoreceptors (41) as well as the effect of cerebral vascular responsiveness on the CO2 reserve. However, the evidence to date is limited in this regard. To apply this fundamental hypothesis to understand the control of breathing and breathing stability in wakefulness and sleep, we need to determine the extent to which this proposed chemoreceptor interaction might influence ventilatory control in the intact, unanesthetized preparation.

Clinical implications.

In general, the relatively small reductions in CO2 reserve by themselves observed in the present study are likely not sufficient to produce instability in healthy people with no other destabilizing disturbances, such as a collapsible upper airway, frequent arousals, hypoxic exposure, high carotid chemoreceptor gain or sensitivity, and/or prolonged circulation time. However, in CHF patients who possess several factors potentially contributing to instability, their impaired cerebrovascular response to CO2 may well be a significant contributing factor to instability and apnea (21). In fact, a high prevalence of central sleep apnea together with a low cerebrovascular response to CO2 have been reported in patients with CHF (18), and cerebral vasodilation induced via captopril reduced eupenic ventilation and increased Pco2 and reduced the number of apnea-hypopneas in these patients (47). Furthermore, there are several other clinical observations also consistent with our experimental findings supporting a significant contribution from cerebrovascular responsiveness to ventilatory instability in sleep. For example, recent work by Ainslie et al.(1) indicates that hypoxia attenuates cerebrovascular reactivity to hypocapnia, which might also contribute to the periodic breathing during sleep at high altitudes. Furthermore, men have more sleep apnea than women, and they also have a lower CBF vasodilatory response to CO2 (24).

In summary, through the reduction in CBF and attenuation of cerebrovascular responsiveness to transient hypocapnia, Indo caused a smaller CO2 reserve via increasing the slope of the ventilatory response to CO2 below eupnea. The index of CO2 reserve provides a readily interpretable measure of the susceptibility for apnea and instability in a given subject and how it changes under varying conditions. These findings, therefore, shed light on the importance of compromised cerebrovascular reactivity in contributing to ventilatory instability during sleep.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Veterans Affairs Research Service, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and American Lung Association of Wisconsin.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ainslie PN, Burgess K, Subedi P, Burgess KR. Alterations in cerebral dynamics at high altitude following partial acclimatization in humans: wakefulness and sleep. J Appl Physiol 102: 658–664, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berend N, Christopher KL, Voelkel NF. The effect of positive end-expiratory pressure on functional residual capacity: role of prostaglandin production. Am Rev Respir Dis 126: 646–647, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruhn H, Fransson P, Frahm J. Modulation of cerebral blood oxygenation by indomethacin: MRI at rest and functional brain activation. J Magn Reson Imaging 13: 325–334, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulow K Respiration and wakefulness in man. Acta Physiol Scand 59, Suppl 209: 1–110, 1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson LA, Ekelund LG, Oro L. Circulatory and respiratory effects of different doses of prostaglandin E1 in man. Acta Physiol Scand 75: 161–169, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caparas SN, Clair MJ, Krombach RS, Hendrick JW, Houck WV, Kribbs SB, Mukherjee R, Tempel GE, Spinale FG. Brain blood flow patterns after the development of congestive heart failure: effects of treadmill exercise. Crit Care Med 28: 209–214, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman RW, Santiago TV, Edelman NH. Effects of graded reduction of brain blood flow on ventilation in unanesthetized goats. Appl Physiol 47: 104–111, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman RW, Santiago TV, Edelman NH. Effects of graded reduction of brain blood flow on chemical control of breathing. J Appl Physiol 47: 1289–1294, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clauss RP, Dormehl IC, Oliver DW, Nel WH, Kilian E, Louw WK. Measurement of cerebral perfusion after zolpidem administration in the baboon model. Arzneimittelforschung 51: 619–622, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyle MG, Oh W, Petersson KH, Stonestreet BS. Effects of INDO on brain blood flow, cerebral metabolism, and sagittal sinus prostanoids after hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H1450–H1459, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day TA, Wilson RJ. A negative interaction between central and peripheral respiratory chemoreceptors may underlie sleep-induced respiratory instability: a novel hypothesis. Adv Exp Med Biol 605: 447–451, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeGiulio PA, Roth RA, Mishra OP, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M, Wagerle LC. Effect of indomethacin on the regulation of cerebral blood flow during respiratory alkalosis in newborn piglets. Pediatr Res 26: 593–597, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dempsey JA, Smith CA, Przybylowski T, Chenuel B, Xie A, Nakayama H, Skatrud JB. The ventilatory responsiveness to CO2 below eupnoea as a determinant of ventilatory stability in sleep. J Physiol 560: 1–11, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duggan CJ, Castle WD, Berend N. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure breathing on lung volume and distensibility. J Appl Physiol 68: 1121–1126, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eriksson S, Hagenfeldt L, Law D, Patrono C, Pinca E, Wennmalm A. Effect of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors on basal and carbon dioxide stimulated cerebral blood flow in man. Acta Physiol Scand 117: 203–211, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fencl V Acid-base balance in cerebral fluids. In: Handbook of Physiology. The Respiratory System. Control of Breathing. Bethesda, MD: Am Physiol Soc, 1986, sect. 3, vol. II, pt. 1, chapt 4, p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fencl V, Vale JR, Broch JA. Respiration and cerebral blood flow in metabolic acidosis and alkalosis in humans. J Appl Physiol 27: 67–76, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Georgiadis D, Sievert M, Cencetti S, Uhlmann F, Krivokuca M, Zierz S, Werdan K. Cerebrovascular reactivity is impaired in patients with cardiac failure. Eur Heart J 21: 407–413, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gómez-Niño A, Almaraz L, González C. Potentiation by cyclooxygenase inhibitors of the release of catecholamines from the rabbit carotid body and its reversal by prostaglandin E2. Neurosci Lett 140: 1–4, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gómez-Niño A, Almaraz L, González C. In vitro activation of cyclo-oxygenase in the rabbit carotid body: effect of its blockade on [3H]catecholamine release. J Physiol 476: 257–267, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Javaheri S A mechanism of central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 341: 949–954, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Liming JD, Corbett WS, Nishiyama H, Wexler L, Roselle GA. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure. Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations. Circulation 97: 2154–2159, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansen AH, De Boeck C, Ioffe S, Chernick V. Indomethacin-induced fetal breathing: mechanism and site of action. J Appl Physiol 57: 360–365, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kastrup A, Happe V, Hartmann C, Schabet M. Gender-related effects of INDO on cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity. J Neurol Sci 162: 127–132, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoo MC Determinants of ventilatory instability and variability. Respir Physiol 122: 167–182, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacy CF, Armstrong LL, Goldman MP, Lance LL. Drug Information Handbook. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp, 2003, p. 633–634.

- 27.Lee CW, Lee JH, Lim TH, Yang HS, Hong MK, Song JK, Park SM, Park SJ, Kim JJ. Prognostic significance of cerebral metabolic abnormalities in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 103: 2784–2787, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markus HS, Vallance P, Brown MM. Differential effect of three cyclooxygenase inhibitors on human cerebral blood flow velocity and carbon dioxide reactivity. Stroke 25: 1760–1764, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McQueen DS The effects of some prostaglandins on respiration in anaesthetized cats. Br J Pharmacol 50: 559–568, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McQueen DS, Belmonte C. The effects of prostaglandins E2, A2 and F2 alpha on carotid baroreceptors and chemoreceptors. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci 59: 63–71, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama H, Smith CA, Rodman JR, Skatrud JB, Dempsey JA. Carotid body denervation eliminates apnea in response to transient hypocapnia. J Appl Physiol 94: 155–164, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parisi RA, Neubauer JA, Frank MM, Santiago TV, Edelman NH. Linkage between brain blood flow and respiratory drive during rapid-eye-movement sleep. J Appl Physiol 64: 1457–1465, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulin MJ, Liang PJ, Robbins PA. Fast and slow components of cerebral blood flow response to step decreases in end-tidal Pco2 in humans. J Appl Physiol 85: 388–397, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poulin MJ, Robbins PA. Influence of cerebral blood flow on the ventilatory response to hypoxia in humans. Exp Physiol 83: 95–106, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajagopalan B, Raine AE, Cooper R, Ledingham JG. Changes in cerebral blood flow in patients with severe congestive cardiac failure before and after captopril treatment. Am J Med 76: 86–90, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A Manual for Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, 1968.

- 37.Reichmuth K, Xie A, Barczi S, Dempsey J. Cerebral blood flow changes and ventilation in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: A67, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt CF The influence of cerebral blood-flow on respiration. I. The respiratory responses to changes in cerebral blood flow. Am J Physiol 84: 22–222, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD, Newton G, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 160: 1101–1106, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skatrud JB, Dempsey JA. Interaction of sleep state and chemical stimuli in sustaining rhythmic ventilation. J Appl Physiol 55: 813–822, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith CA, Chenuel BJ, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. The apneic threshold during non-REM sleep in dogs: sensitivity of carotid body vs. central chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol 103: 578–586, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith CA, Nakayama H, Dempsey JA. The essential role of carotid body chemoreceptors in sleep apnea. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 81: 774–779, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith CA, Rodman JR, Chenuel BJ, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Response time and sensitivity of the ventilatory response to CO2 in unanesthetized intact dogs: central vs. peripheral chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol 100: 13–19, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.St. Croix CM, Cunningham DA, Paterson DH. Nature of the interaction between central and peripheral chemoreceptor drives in human subjects. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 74: 640–646, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.St. Lawrence KS, Ye FQ, Lewis BK, Weinberger DR, Frank JA, McLaughlin AC. Effects of INDO on cerebral blood flow at rest and during hypercapnia: an arterial spin tagging study in humans. J Magn Reson Imaging 15: 628–635, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takakura AC, Moreira TS, Colombari E, West GH, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Peripheral chemoreceptor inputs to retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) CO2-sensitive neurons in rats. J Physiol 15: 503–523, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walsh JT, Andrews R, Starling R, Cowley AJ, Johnston ID, Kinnear WJ. Effects of captopril and oxygen on sleep apnoea in patients with mild to moderate congestive cardiac failure. Br Heart J 73: 237–241, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Q, Paulson OB, Lassen NA. INDO abolishes cerebral blood flow increase in response to acetazolamide-induced extracellular acidosis: a mechanism for its effect on hypercapnia? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 13: 724–727, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolsink JG, Berkenbosch A, DeGoede J, Olievier CN. The influence of indomethacin on the ventilatory response to CO2 in newborn anaesthetized piglets. J Physiol 477: 339–345, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie AL, Skatrud JB, Puleo DS, Rahko PS, Dempsey JA. Apnea-hypopnea threshold for CO2 in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Critical Care Med 165: 1245–1250, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie A, Skatrud JB, Khayat R, Dempsey JA, Morgan B, Russell D. Cerebrovascular response to carbon dioxide in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 371–378, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie A, Skatrud JB, Morgan B, Chenuel B, Khayat R, Reichmuth K, Lin J, Dempsey JA. Influence of cerebrovascular function on the hypercapnic ventilatory response in healthy humans. J Physiol 577: 319–329, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie A, Skatrud JB, Puleo DS, Dempsey JA. Influence of arterial O2 on the susceptibility to posthyperventilation apnoea during sleep. J Appl Physiol 100: 171–177, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie A, Reichmuth K, Dempsey J, Barczi S. Effect of cerebral blood flow on respiration in humans during sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: A69, 2007. [Google Scholar]