Abstract

Background

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the major risk factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Nevertheless, transgenic mice which express the whole HCV polyprotein (HCV-Tg) do not develop HCC. Whereas chronic HCV infection causes inflammation in patients, in HCV-Tg mice, the host immune reaction against viral proteins is lacking. We aimed to test the role of HCV proteins in HCC development on the background of chronic inflammation in vivo.

Methodology/Principal Findings

We crossed HCV-Tg mice that do not develop HCC with the Mdr2-knockout (Mdr2-KO) mice which develop inflammation-associated HCC, to generate Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice. We studied the effect of the HCV transgene on tumor incidence, hepatocyte mitosis and apoptosis, and investigated the potential contributing factors for the generated phenotype by gene expression and protein analyses. The Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females from the N2 generation of this breeding (having 75% of the FVB/N genome and 25% of the C57BL/6 genome) produced significantly larger tumors in comparison with Mdr2-KO mice. In parallel, the Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females had an enhanced inflammatory gene expression signature. However, in the N7 generation (having 99.2% of the FVB/N genome and 0.8% of the C57BL/6 genome) there was no difference in tumor development between Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg and Mdr2-KO animals of both sexes. The HCV transgene was similarly expressed in the livers of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females of both generations, as revealed by detection of the HCV transcript and the core protein.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that the HCV transgene accelerated inflammation-associated hepatocarcinogenesis in a host genetic background-dependent manner.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a significant health care burden worldwide, and chronic inflammation is a major risk factor for the development of HCC. The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the major etiological HCC agents: it induces chronic liver inflammation and is responsible for the increased incidence of HCC in the developed world [1]. Although multiple cell culture models demonstrated oncogenic potential of several HCV proteins, most transgenic mouse models expressing these proteins did not develop HCC [2]. Furthermore, non infectious metabolic conditions causing chronic hepatitis also expose humans to an increased risk of developing HCC. Thus, determinants of HCC development on the background of chronic inflammation could be attributed to genetic/gender background, pathogen-derived or environmentally-dependent factors [3]–[5]. The aim of this study is to investigate the interplay between the factors contributing to the development of HCC in a mouse model expressing HCV proteins.

The previously generated HCV transgenic (HCV-Tg) mouse models produced inconsistent results concerning the role of HCV proteins in HCC development. Only one model that expressed the HCV core protein developed HCC with high incidence [6], and two models that expressed the HCV core together with E1 and E2 proteins developed HCC with very low incidence [7], [8]. However, other models containing similar transgenes, albeit produced in other laboratories, did not develop HCC [2]. Two groups created HCV-Tg mice expressing the whole HCV polyprotein [7], [9], however, none of these models are developing HCC (although in one model, HCC development was reported [7], this phenotype disappeared in the progeny throughout the next generations [10]). In transgenic animals, there is no inflammatory reaction against proteins expressed by a transgene, whereas in HCV-infected patients, the liver is inflamed. On the other hand, genetic models with chronic liver inflammation develop HCC at a high rate [11]–[13]. We and others have reported the importance of inflammatory mediators in HCC development [14]–[17].

In order to explore the hypothesis that HCV proteins may accelerate inflammation-associated liver carcinogenesis, and to identify and characterize the signaling pathways most likely to be affected, we crossed one of the existing HCV-Tg models, which produced detectable levels of HCV proteins [9], with the Mdr2 knockout (Mdr2-KO) mice, a model of inflammation-associated HCC. The Mdr2-KO mice develop liver tumors in about 100% of animals by the age of 16 months on the FVB/N genetic background; initially, this model was generated in the 129/OlaHsd strain, but due to a low fertility of the resulting mutants, the Mdr2-KO mutation was transferred into the FVB/N strain [11], [18]. We monitored HCC development in these hybrid mice by ultrasound, and, upon sacrifice, analyzed mitotic, apoptotic and gene expression patterns in their tumorous and non-tumorous liver tissues.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Mice were maintained at the Specific Pathogen-Free (SPF) unit, Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University, under a 12 h light/dark cycle, and provided with food and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were performed according to national regulations and guidelines of the Institutional Animal Welfare Committee (NIH approval number OPRR-A01-5011). Founders of the FVB.129P2-Abcb4tm1Bor (Mdr2-KO; old name FVB.129P2-Pgy24tm1Bor) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, USA) [11]. Transgenic mice expressing the whole HCV 1b polyprotein were kindly provided by Prof. N. La Monica (IRBM, “P. Angeletti”, Pomezia, Italy) [9]. Double Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice were produced by crossing between homozygous Mdr2-KO and HCV-Tg mice, and by backcrosses of the resulting F1 hybrid (both Mdr2- and HCV-heterozygous) with the parental Mdr2-KO strain. Appearance of tumors was monitored by ultrasound from the age of 10 months, using an ATL 5000 device (ATL, Bothell, WA) with linear transducer (12–15 mHz). Mice were sacrificed at the age of 14 months, when tumor appearance was detected in most Mdr2-KO mice.

Genotyping

DNA from mouse tails or livers was purified by either the Wizard® Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI) or by the Puregene® DNA isolation kit (Gentra systems, Minneapolis, MN). Genotype analysis was carried out by PCR analysis of DNA extracted from mouse tails using HCV transgene, Mdr2 and Neo primers (primers sequences are specified in the Table 1).

Table 1. PCR primers.

| Gene | Sense primer | Antisense primer |

| HCV transgene | 5′-ggcgcacatggcatcctc-3′ | 5′-gccaccgcaaggtctcgt-3′ |

| Mdr2 | 5′-gctgagatggatcttga-3′ | 5′-tagccagatgatgg-3′ |

| Neo | 5′- aagaccgacctgtccg-3′ | 5′-tattcggcaagcaggcatcg-3′ |

| Hprt | 5′- gttaagcagtacagccccaaa-3′ | 5′- agggcatatccaacaacaaactt-3′ |

| Gtf3c2 | 5′- ggtgtcacagtggctcaaga-3′ | 5′- aatggctgcttggagagaaa-3′ |

| Sec24c | 5′- tccacaacttggccctaaac-3′ | 5′- aaaccagctgccgaacatag-3′ |

| Cyp4a31 | 5′- acaaggaccttcgtgctgag-3′ | 5′- cttgggacaggtgggtagag-3′ |

| Erbb4 | 5′- atggccttccaacatgactc-3′ | 5′- cacctgccatcacattgttc-3′ |

| Esm1 | 5′- gggatggaatgcaaagagac-3′ | 5′- agcgttcccttctccaatct-3′ |

| Id3 | 5′- gaggagcttttgccactgac-3′ | 5′- tgaagagggctgggttaaga-3′ |

| Ifrd1 | 5′- tccaagcctcctttcttgtg-3′ | 5′- gaccgctgctttctcttgtc-3′ |

| Ndrg1 | 5′- tgtcccgagagctacatgac-3′ | 5′- ctcttgcaggagaccagtga-3′ |

| Nrg1 | 5′- tcggtcagaacgaaacaaca-3 | 5′-tcgtggagtgatgagctgtg-3′ |

| Ptgds | 5′- aaccagtgtgagaccaagatca-3′ | 5′- ttggtgcctctgctgaatag-3′ |

| Sox4 | 5′- ggcttcctaccttgcaacaa-3′ | 5′- tcgattgcagttcacgagag-3′ |

| Styk1 | 5′- atggatggcctgctctatga-3′ | 5′- caggcccagatgacaaagtt-3′ |

| Tff2 | 5′- cttggtgtttccacccactt-3′ | 5′- caccagggcacttcaaaga-3′ |

| Ubd | 5′- ggatttccaacccagctactc-3′ | 5′- gcagaaggatctggtcctgta-3′ |

| Vnn1 | 5′- gggagacaagaagccgtgta-3′ | 5′- aacaggtgaagacgccaaac-3′ |

Harvesting of mouse tissue

Non fasting mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Livers were rapidly excised and weighed; a part of the liver was fixed with 4% buffered formaldehyde for histological analysis, and the remaining tissue was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further use.

RNA extraction and analysis

Total RNA was isolated from snap frozen mouse liver tissues with the Trizol® reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described by the manufacturer. Whole genome gene expression profiling of RNA samples was performed using Affymetrix GeneChip® Mouse Exon 1.0 ST Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

Calculation of gene expression values

The raw data were processed by the Partek® Genomics Suite™ (Partek GS) (Partek Inc., St. Louis, MO) software. RMA algorithm was applied for summarization, and the normalization was performed by the quantile method. The normalized expression values were processed by the Partek batch removing tool. The analysis was repeated twice: on “extended” and “core” subsets of probe-sets and when the probe-set mean was applied for evaluation of transcript cluster expression level. The processed data were submitted either to fold-change analysis with a threshold of 1.85, to hierarchical clustering with the Eisen software [19], or to SPIN analysis (sorting points into neighborhoods (sorting algorithm)) [20], which enables arrangement of expression profiles in the order of similarity (“side-to-side” sorting variant).

Analysis of alternative splicing

The alternative splicing calculation was performed using the definition of splicing index as average log2 transformed relations between expression levels of individual probe-sets (representing individual exons) and transcript clusters (evaluation of gene expression level) [21]. Statistical significance of the differences between splicing indices in different experimental groups was evaluated with the ANOVA test for comparison between the non-matched samples or paired T-test for matched samples (tumors and non-tumorous tissues). The significant difference in the splicing index was considered to be a sign of change of the tested exon inclusion levels. Only probe-sets and transcripts with a maximal expression level >5 (in log2 scale) were used.

Confirmation of differential gene expression by RT–PCR

Reverse transcription of total RNA was performed using the MMLV Reverse Transcriptase and random hexamer primers (Promega, Madison, WI). Semi-quantitative PCR was performed using Super-therm Taq Polymerase (JMR, UK). For each gene, the cDNA concentration and the number of PCR cycles were established in the linear amplification range. Expression levels for each gene were normalized against one of the following housekeeping genes: Hprt, Gtf3c2 or Sec24c (PCR primers are specified in the Table 1). Pictures of agarose gels were taken by B.I.S. 202D BioImaging System (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech., USA). The intensities of bands and p-values were obtained using the ImageGauge Ver. 4.0 program for quantification of images (Fujifilm Science Lab.). Real-time PCR was run in triplicates using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, primers, probe sets, and the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector System from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Threshold cycle numbers (Ct) were determined with the Sequence Detector Software (version 1.6; Applied Biosystems) and transformed using the ΔCt method as described by the manufacturer. The relative quantification values for each gene were normalized against the endogenous housekeeping gene Sec24c, which was one of the most uniformly expressed genes in all RNA samples subjected to global gene expression profiling. Relative quantitation value of each tumorous sample was compared to the relative quantitation value of its matched non-tumorous sample.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed on four-micrometer-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver tissue sections by standard procedures. Antigen retrieval was done with citrate buffer, pH 6.0 (HCV core, β-catenin, galectin-1, and Ubd/Fat10) or glycine buffer, pH 9.0 (cyclin D1) in a microwave. Primary antibodies were: anti-HCV-core Ab (ABR Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO), rabbit anti-cyclin D1 SP4 clone (Diagnostic Biosystems, Pleasanton, CA), anti-β-catenin (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), anti-galectin-1 and anti-Ubd/Fat10 (SC-19277 and SC-51086, respectively, both from Santa Cruz biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). We used the SuperPicture™-HRP polymer conjugate broad spectrum kit (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) as secondary antibody for HCV core and Cyclin D1, Envision®+HRP labeled polymer (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) for β-catenin, LSAB®+System-HRP (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for galectin-1, and HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for Ubd/Fat10 staining. Color development with diaminobenzidine was done using the Zymed kit as mentioned above. Scores for galectin-1 staining were assessed according to evaluation of average level of staining all along the section.

Statistical analysis of the data

Significance of the difference in tumor incidence between mouse groups was tested by Chi-Square-test; significance of differences in the levels of blood enzymes, in the levels galectin-1 immunostaining, in the frequency of mitosis and apoptosis, and in the semi-quantitative RT-PCR was tested by t-test. Statistical evaluation of differential expression between the experimental groups was performed using ANOVA test.

Results

Effect of the HCV transgene on hepatocarcinogenesis in Mdr2-KO mice

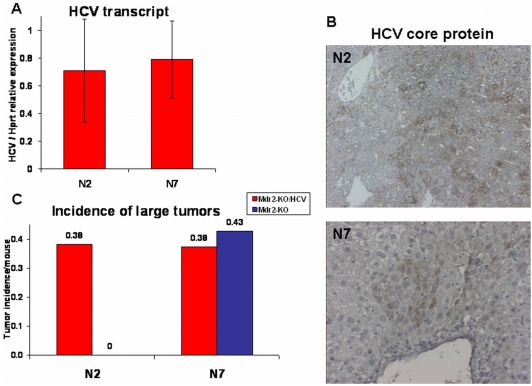

The first breeding between homozygous HCV-Tg and Mdr2-KO mice (having C57Bl/6 and FVB/N genetic backgrounds, respectively) produced a generation of HCV- and Mdr2-heterozygotes (Fig. S1). The second backcross of these mice to the maternal Mdr2-KO strain produced the N2 generation which contained 25% of the C57Bl/6 genetic background. We continued to produce backcrosses till the N7 generation, an incipient congenic strain containing only 0.8% of the donor C57Bl/6 genetic background and 99.2% of the recipient FVB/N genetic background. The produced hybrid mice were followed for HCC development, and comparison between the N2 and N7 generations was performed. Independently of the presence of the HCV transgene, Mdr2+/− mice did not develop HCC upon sacrifice at 18 months of age, whereas all Mdr2-KO mice did produce liver tumors at 14 months of age (Table 2). Most tumors were well-differentiated HCC as determined by previously described criteria [18] and by immunostaining for reticulin fibers (not shown). Immunohistochemical analysis of liver tissues from HCV-Tg mice with antibodies to the core protein showed non-uniform distribution of HCV transgene expression both in Mdr2-KO and Mdr2-heterozygous mice. Levels of the HCV transgene expression were similar between Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice from the N2 and N7 generations (Fig. 1, A and B). However, a significant difference in the incidence of large tumors was observed upon comparing N2 female mice with and without the HCV transgene: only N2 female mice with the HCV transgene had tumors with diameters over 1 cm (p = 0.0445; Table 2 and Fig. 1C). In contrast, in mice from the N7 generation, the incidence of large tumors was independent of the presence of the HCV transgene and was similar to that in Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice from the N2 generation. The 25% of the C57Bl/6 genetic background present in the N2 generation had a tumor suppressive effect in the Mdr2-KO mice not having the HCV transgene (Fig. 1C). There was a statistically significant reduced incidence of tumors with a diameter over 1 cm between the animals from the N2 and N7 generations (Chi-Square-tests for both all mice (p = 0.0237) and for females (p = 0.0299); Table 2). The tumor promoting effect of the HCV transgene was statistically significant only on the partially suppressive N2 genetic background, and only in females (p = 0.0445).

Table 2. Incidence of HCC in 14-month-old Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg and Mdr2-KO mice from the N2 and N7 generations.

| Incidence of HCC in N2 | Tumor size: >1.2 cm | Tumor size: 1–1.2 cm | Tumor size: 0.8–1 cm | Tumor size: 0.5–0.7 cm | ||

| genotype | sex | No. of mice | ||||

| MDR2-KO/HCV | m | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| f | 13 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| all | 29 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |

| MDR2-KO | m | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| f | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| all | 18 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

Figure 1. HCV transgene expression and incidence of large liver tumors in female mice from the N2 and N7 generations.

(A) Similar expression levels of the HCV transcript in 14-month-old Mdr2-KO/HCV mice from the N2 and N7 generations. Average levels of the HCV transcript were determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR relative to expression level of the housekeeping gene Hprt in 5 females from the N2 generation and in 15 females from the N7 generation. (B) Similar expression of the HCV core protein in 14-month-old Mdr2-KO/HCV mice from the N2 and N7 generations. Representative immunohistochemical staining against HCV core protein in females from the N2 and N7 generations (magnification: ×200). (C) Higher incidence of large liver tumors (diameter over 1 cm) per mouse in 14-month-old Mdr2-KO/HCV compared to Mdr2-KO female mice from the N2, but not from the N7 generations. Incidence of all tumors is shown in Table 2. Red bars – Mdr2-KO/HCV group, blue bar – Mdr2-KO group.

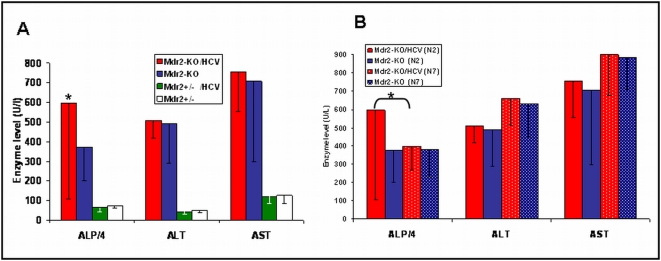

Higher levels of liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase) were found in the serum of all Mdr2-KO mice compared to Mdr2+/− controls (Fig. 2A), as expected [15]. However, the only statistically significant difference between Mdr2-KO/HCV mice and Mdr2-KO mice from the N2 generation was in the level of alkaline phosphatase, found in females only (p = 0.04). Nevertheless, there was no direct correlation between the level of alkaline phosphatase and liver tumor load/incidence in individual Mdr2-KO/HCV mice. Similarly, high levels of serum liver enzymes were also measured in Mdr2-KO mice of the N7 generation; however, the level of alkaline phosphatase was not specifically increased in the Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females compared to Mdr2-KO females not expressing the HCV transgene (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Levels of liver enzymes in the serum of 14-month-old Mdr2-KO female mice.

Liver enzymes: Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured in serum of 14 month old female mice. Graph represents average levels ±SD. (A) Comparison of enzymes levels (U/l) between Mdr2-KO and Mdr2+/− with and without HCV-Tg from the N2 generation. (B) Comparison of enzymes levels (U/l) of Mdr2-KO/HCV and Mdr2-KO females from N2 and N7 generation. Statistically significant difference was found in ALP levels between Mdr2-KO/HCV females and Mdr2-KO females of the N2 generation only (* p = 0.04).

Effect of the HCV transgene on mitosis and apoptosis in Mdr2-KO mice

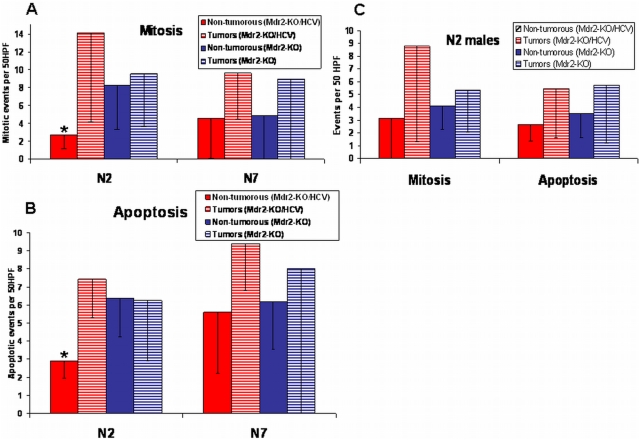

To investigate the potential mechanisms for the effect of the HCV transgene on hepatocarcinogenesis, we compared mitotic and apoptotic events in non-tumorous and tumorous liver tissues of the Mdr2-KO and Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females from the N2 and N7 generations (Fig. 3A – mitosis, Fig. 3B - apoptosis) and of the males from the N2 generation (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, we observed a statistically significant decrease of mitosis (p<0.016) and apoptosis (p<0.002) in the non-tumorous tissues of the Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females from the N2 generation only; however, once the anti-mitotic effect of the HCV transgene was bridged in tumors, then mitosis was enhanced in both female and male mice from the N2 generation (Fig. 3A and Fig. 3C). This effect was more prominent in female mice, although it did not reach statistical significance. The presence of the highly proliferative tumors with diameters of up to 1 cm in Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females indicates a possible reason for the appearance of large tumors with diameters over 1 cm in this experimental group (Fig. 1C) as well. In the N7 females, the anti-mitotic effect of the HCV transgene on non-tumorous liver tissue was absent, and the mitotic activities of tumors in the Mdr2-KO and Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females were similar to each other and to those of the Mdr2-KO females from the N2 generation (Fig. 3A). The levels of apoptosis in tumors were similar between N2 and N7 females, independent of the presence of the HCV transgene (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Mitotic and apoptotic events in the livers of mice from the N2 and N7 generations.

Events were counted per 50 HPF ±SD in H&E stained liver sections of tumors (0.3–1 cm diameter) and non-tumorous tissue samples from 14-month-old mice. (A) Reduced mitotic events (p = 0.016) in non-tumorous liver tissues of Mdr2-KO/HCV females compared to Mdr2-KO female mice from the N2, but not from the N7 generations. (B) Reduced apoptotic events (p = 0.002) in non-tumorous liver tissues of Mdr2-KO/HCV females compared to Mdr2-KO female mice from the N2, but not from the N7 generations. (C) Similar intensities of mitotic and apoptotic events in the livers of male mice from the N2 generation. There was no statistically significant difference between groups.

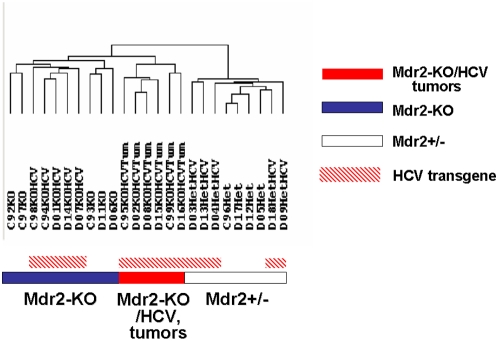

Gene expression profiling analysis

In an effort to delineate the molecular mechanisms associated with the tumor promoting effect of the HCV transgene in Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg N2 females, we performed a genome scale gene expression profiling on livers of 14-month-old female mice. Non-tumorous liver tissues of Mdr2-KO, Mdr2+/−, Mdr2+/−/HCV-Tg, and Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg female mice from the N2 generation, as well as all large tumors (diameters over 1 cm) of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females, were analyzed (Fig. 4). In hierarchical clustering, the Mdr2 genotype and the tumor phenotype were major clustering forces separating the samples into three main clusters: Mdr2-KO, Mdr2+/− and tumors. Remarkably, in the cluster of healthy Mdr2+/− mice, the HCV transgene was a destabilizing factor, whereas in the chronically inflamed Mdr2-KO background, it was a stabilizing factor providing clusterization of all HCV-Tg samples into one subcluster. Similarly, Mdr2-KO mutation was the main factor contributing to the alternative splicing between the experimental groups (Table S1). Overall, the contribution of the HCV transgene in both differential gene expression (Fig. S2) and alternative splicing (Table S1) was only marginal. However, supervised analysis of genes with a tendency to differential expression between Mdr2-KO and Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg samples revealed a substantial overlap of pathways affected by the HCV transgene and the Mdr2-KO mutation (Table S2). This overlap is comprised of all arms of the immune system, including the innate, humoral and, to some extent, the adaptive responses; many of these genes were also similarly differentially expressed between Mdr2+/− and Mdr2+/−/HCV-Tg samples (data not shown).

Figure 4. Hierarchical clustering of expression profiles of liver tissue samples subjected to whole genome expression profiling.

Average linkage hierarchical clustering of liver tissue samples from females of the N2 generation was performed on 5,000 genes with highest STD values using the software from Michael Eisen's Laboratory (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and University of California, Berkeley; http://rana.lbl.gov/EisenSoftware.htm). The Mdr2 genotype and the tumor phenotype were major clustering forces, whereas the contribution of the HCV transgene in clustering was only marginal.

Confirmation of differential gene expression

Differential expression of selected genes was further confirmed by RT-PCR (Table 3). These genes are involved in the regulation of immune/inflammatory response (Lgals1, Ptgds, Tff2, Ubd), tumor angiogenesis (Lgals1, Esm1, Ndrg1), epidermal growth factor signaling (Erbb4, Nrg1), response to tissue injury (Tff2, Vnn1), and gene transcription (Id3, Ifrd1). Some of these genes (Lgals1, Nrg1, Ubd) have been already identified previously as HCV-dependent [22]–[25]. More detailed information on the confirmed genes and their potential roles in carcinogenesis can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Confirmation of the differential gene expression by RT-PCR.

| Gene symbol | Accession number | Differential expression$ | Ttest& | Gene name | Known or suggested role of the gene in cancer |

| Cyp4a31@ | NM_201640 | KO>NT | p = 0.001 | Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 31 | Iron ion binding [49]. |

| Erbb4@ | NM_010154 | T>NT | p = 0.003 | V-erb-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4 | Activated by neuregulins; increases proliferation potential of cancer cells [50]. |

| Esm1@ | NM_023612 | T>NT | p = 0.009 | Endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 | Preferentially expressed in tumor endothelium [51]. |

| Gnmt# | NM_010321 | T<NT | Glycine N-methyltransferase | Downregulated in HCC [52]. | |

| Id3@ | NM_008321 | T<NT | p = 0.04 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 3 | Expression in HCC decreases with tumor dedifferentiation [53]. |

| Ifrd1@ | NM_013562 | T>NT | p = 0.04 | Interferon-related developmental regulator 1 | Regulates differentiation of epithelial cells [54]. |

| Ndrg1@ | NM_008681 | T>NT | p = 0.02 | N-myc down-stream regu-lated gene 1 | Mediates prolife-ration and invasion of HCC cells [55]. |

| Nrg1@ | NM_178591 | T>NT | p = 0.006 | Neuregulin 1 | Upregulated in HCV-induced HCC [24]. |

| Ptgds@ | NM_008963 | KO<NT | p = 0.04 | Prostaglandin D2 synthase | Antiproliferative in prostate cancer [56]. |

| Sox4@ # | NM_009238 | KO>NT | p = 0.003 | SRY-box containing gene 4 | Positive regulator of HCC cells' apoptosis [57]. |

| Styk1@ | NM_172891 | T>NT | p = 0.006 | Serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase 1 | Induces tumorige-nesis and metastasis in nude mice [58]. |

| Tff2@ | NM_009363 | KO<NT | p = 0.02 | Trefoil factor 2 | Promotes epithelial-cell restitution, cont-rols inflammation and systemic immune responses [59]. |

| Ubd@ | NM_023137 | T>NT | p = 0.03 | Ubiquitin D (FAT10) | Upregulated in various cancers including HCC [27], resulting in chromo-some instability [60]. |

| Vnn1@ | NM_011704 | T>NT | p = 0.01 | vanin 1 | Regulates response to oxidative injury in epithelial cells [61]. |

Confirmed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR.

Confirmed by real time RT-PCR (Sox4 was confirmed by both methods).

T – tumorous and NT – matched non-tumorous liver tissues of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females; KO - non-tumorous liver tissues of Mdr2-KO females.

p-values for semi-quantitative RT-PCR are provided (see “Materials and methods”).

Up-regulation of two proteins, galectin-1 (encoded by the Lgals1 gene) and diubiquitin (encoded by the Ubd/Fat10 gene), was confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Galectin-1 modulates innate and adaptive immune responses; its over-expression in many types of tumors and/or surrounding tissues promotes tumor progression by inhibition of anti-tumor immune response [26]. Galectin-1 was overexpressed in non-tumorous liver tissue of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice, mostly in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes in zones 1 and 3, in endothelial cells, and on the luminal side of cholangiocyte membranes (Fig. 5). Diubiquitin is involved in the maintenance of spindle integrity during mitosis and is highly upregulated in human HCC [27]; it was detected mostly in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes in the tumors of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice, and, to a lesser degree, in non-tumorous liver tissues of Mdr2-KO mice with or without the HCV transgene (Fig. 6). Remarkably, diubiquitin was detected in the hepatocyte nuclei only in large tumors of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice, similar to its nuclear localization in human HCC [27].

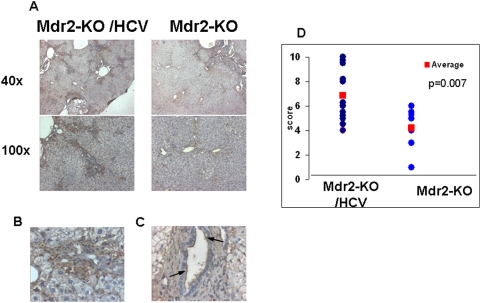

Figure 5. Higher expression of galectin-1 in the livers of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg N2 females.

(A–C) Immunohistochemical staining of non-tumorous liver tissues of 14-month-old Mdr2-KO and Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females from N2 generation with an antibody specific to galectin-1. (A) Left panel: Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg; right panel: Mdr2-KO females. Magnification: upper panel ×40, lower panel ×100. (B) Cytoplasmic staining of hepatocytes in Mdr2-KO/HCV livers. Magnification ×400. (C) Staining of luminal side of cholangiocytes' membranes (indicated by arrows) in Mdr2-KO/HCV livers. Magnification ×400. (D) Scores of the immunostaining level for all liver samples in each group are shown in blue circles; average scores of each group are shown in red squares; p = 0.007 between the groups.

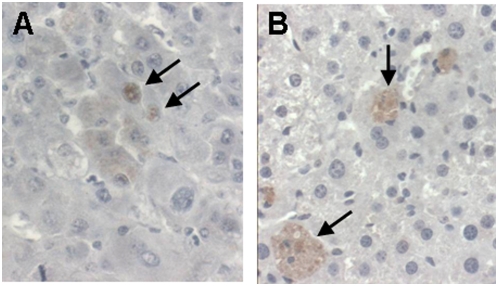

Figure 6. Nuclear expression of diubiquitin in tumors and its cytoplasmic expression in non-tumorous hepatocytes.

Immunohistochemical staining of 14-months-old Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg N2 females with an antibody specific to diubiquitin. (A) Nuclear staining of hepatocytes in tumorous tissue (arrows). (B) Cytoplasmic staining of hepatocytes in non-tumorous liver tissue (arrows). Magnification: ×400.

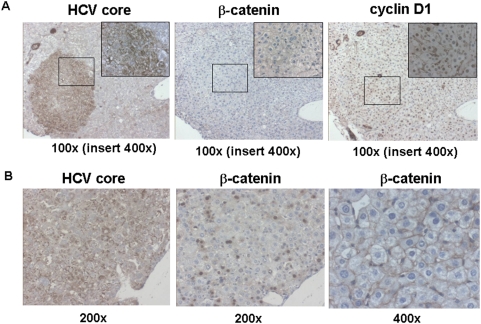

Testing of other known effects of the HCV transgene expression

We searched for a correlation between the local level of the HCV transgene expression (revealed by immunohistochemical detection of the HCV core protein) and other oncogenic markers. There was no correlation between the level of HCV transgene expression and the presence of dysplastic nodules in Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice. It was shown previously that HCV-associated HCC is characterized by increased frequency of β-catenin mutations and by activation of β-catenin signaling [28], [29]. We reported recently that in the non-tumorous liver of Mdr2-KO mice, β-catenin signaling is inhibited while the nuclear level of cyclin D1 is increased [18]. The expression level of the HCV transgene in hepatocytes of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice correlated neither with the nuclear level of cyclin D1 nor with the cytoplasmic/nuclear level of β-catenin (a typical example shown in Fig. 7A). However, in some rare cases, high HCV transgene expression correlated with nuclear localization of β-catenin (Fig. 7B). One of the six tumors analyzed by whole genome gene expression profiling was characterized by a prominent upregulation of the β-catenin-activated genes and by rare scattered β-catenin-positive hepatocyte nuclei (data not shown).

Figure 7. Immunohistochemical detection of the HCV core, β-catenin and cyclin D1 proteins in the liver of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice.

(A) A typical example of the absence of correlation between the expression of the HCV core and either nuclear level of cyclin D1, or cytoplasmic/nuclear level of β-catenin proteins in hepatocytes. Magnification: ×100. Inserts contain the framed regions magnified ×400. (B) A rare example of the correlation between the expression of the HCV core and nuclear level of β-catenin proteins in hepatocytes (first two panels; magnification: ×200). Third panel: a typical membrane-associated pattern of β-catenin expression in hepatocytes of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice. Magnification: ×400.

Discussion

The molecular mechanisms of HCV-induced HCC development are still not well understood; one of the main questions is whether HCC develops due to chronic inflammation or whether HCV proteins are endowed with some oncogenic activity. Multiple cell culture models have demonstrated the oncogenic potential of several HCV proteins; however, most transgenic mouse models expressing HCV proteins did not develop HCC [2]. Similarly, none of the two previously generated transgenic mouse models expressing the whole HCV polyprotein is developing HCC [7], [9], [10]. Taking into account that in mouse transgenic models there is no host immune reaction against expressed viral proteins, we explored whether HCV proteins would accelerate inflammation-associated hepatocarcinogenesis. We bred mice expressing the whole HCV polyprotein with Mdr2-KO mice, a model of inflammation-associated HCC, and monitored HCC development in two generations of hybrid mice: N2 and N7, containing 25% and 0.8% of C57Bl/6 genetic background, respectively. We demonstrated, for the first time, that a transgene expressing the whole HCV polyprotein accelerates inflammation-associated hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo in a host genetic background-dependent manner: only in the N2 generation and only in females. Remarkably, our previous studies of Mdr2-KO mice [15] demonstrated that chronic liver disease at an early precancerous stage in this HCC model shares many features characteristic of chronic HCV infection and HCV-induced cirrhosis in patients: hepatocyte G1 arrest and up-regulation of genes Mcm2 [30], Cxcl9, Lgals3, Iqgap1, Lum, Col6a3, Igfbp7, Vim, Ablim, Mpp1 [31], Igfbp1, Itgb1, Jun, Ctgf [32]. This similarity was further confirmed by a significant overlap of pathways affected by the HCV transgene and the Mdr2-KO mutation revealed in the current study (Table S2).

The 25% of C57Bl/6 genetic background had a tumor-suppressive effect on HCC development in the N2 mice not having the HCV transgene, in accord with a well known low susceptibility of the C57Bl/6 mice to tumors [33]. Thus, in the PyMT mouse model of breast cancer, C57Bl/6 mice and F1 hybrids between the C57Bl/6 and FVB/N strains had more prolonged primary tumor latency than the FVB/N mice [34], [35]. Remarkably, the effect of inducible nitric oxide synthase deficiency on mammary tumor development and metastasis was prominent in the C57Bl/6 genetic background, where tumors developed slowly, but was not observed in the FVB/N genetic background, where tumors developed quickly [34]. In the Ras-induced skin squamous carcinoma model, the low susceptibility of the C57Bl/6 strain and the high susceptibility of the FVB/N had been attributed to a polymorphism in the Ptch gene [36]. Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that inactivation of the Nox2 gene in the mutant Sod1 mouse model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis significantly increased survival when mice were of mixed genetic background [37], but had very modest effect on the inbred C57Bl/6 strain [38]. In accord with these findings, our data demonstrate that for mouse models of human diseases, a specific genetic background may be found where manifestations of the disease and/or therapeutic treatments will be the most prominent.

The female-specific effect of the HCV transgene raises a question about the relevance of this model to human disease, since it is widely accepted that human HCC is more prevalent in males. The typical average ratio of males∶females among HCC patients is 3∶1 [39], however, this proportion depends on the etiology of the disease: among HBV-infected patients, it is about 6∶1, whereas among HCV-infected patients, it is about 1.7∶1 [40]. Moreover, when other higher HCC risk factors in males such as alcohol consumption are taken into account, the normalized risk of HCC among HCV-infected patients may be higher for females [41]. Therefore, the appearance of the tumor-promoting effect of the HCV transgene seen only in females in the described model may have a physiological significance. Recently, it was demonstrated that in chemically induced hepatocarcinogenesis in C57Bl/6 mice, the estrogen-mediated inhibition of IL-6 production is responsible for a lower risk of liver cancer in females [3]. However, in the Mdr2-KO mice, the risk for liver cancer is similar in both genders [11], [42], suggesting that there are probably other mechanisms regulating hepatocarcinogenesis in this model of chronic inflammation-associated HCC.

Comparison of mitotic and apoptotic events in non-tumorous liver tissues of the Mdr2-KO and Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice revealed a statistically significant decrease of mitosis and apoptosis in the Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg females from the N2 generation. Interestingly, similar effects of the transgene expressing the HCV open reading frame on the untransformed human hepatocytes have been demonstrated recently: absence of the direct oncogenic activity, inhibition of cell proliferation, and up-regulation of genes involved in innate immune response/inflammation [43]. However, in tumors, an inverse tendency took place: Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice had higher levels of both mitosis and apoptosis, whereas in Mdr2-KO mice, the levels of mitosis and apoptosis in non-tumorous and tumorous tissues were similar. These findings suggest that the accelerating effect of the HCV transgene on hepatocarcinogenesis in this model is most probably due to promotion of tumor proliferation by the HCV transgene. Similarly, the difference in liver cancer susceptibility between the C3H/He and C57Bl/6 strains has been attributed to a dissimilar tumor cell proliferation between these two groups, but not to intensity of apoptosis in their livers [44]. High standard errors observed in the current study for many parameters at the tumorous stage of the disease (e.g., hepatocyte's apoptotic and mitotic frequencies) were most probably caused by a prolonged chronic liver disease associated with induction of different homeostatic mechanisms in the mutant mice.

The tumor promoting effect of the HCV transgene may be explained both by upregulation of pro-tumorigenic genes as Ubd, Erbb4, Nrg1, Ndrg1, Styk1 (Table 3), and by evasion of host defense response by viral proteins [45], [46]. Over-expression of the galectin-1 protein in the liver of Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice may also cause inhibition of anti-tumor immune response [26]. One of the known differences between the C57Bl/6 and FVB/N inbred strains is that the latter is C5 complement-deficient. The important role of C5 and its receptor C5a in host inflammatory reactions [47] suggests that this factor may be responsible for the observed differences in HCC development between the N2 and N7 generations. Interestingly, comparison of differentially expressed genes (Mdr2-KO relative to control mice) of the N2 generation and of FVB/N Mdr2-KO mice aged 12 months [15] or 16 months [18], previously published by our group, revealed significant up-regulation of the complement component C9 in the Mdr2-KO livers of the N2 generation (4-fold; p = 0.0066), but not in FVB/N Mdr2-KO mice. And conversely, inflammatory markers Aif1, Cd36, Cd44 and Spp1 (osteopontin) were up-regulated in FVB/N Mdr2-KO mice at all tested ages, but not in the Mdr2-KO livers of the N2 generation.

This study demonstrates that the HCV transgene accelerated inflammation-associated hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo in a host genetic background-dependent manner, thus emphasizing the significance of the host genotype in HCV manifestations. This accelerating effect was prominent in the mixed, partially tumor-suppressive, FVB/N×C57Bl/6 genetic background, and is most probably due to promotion of tumor proliferation by the HCV transgene. Despite multiple reports on the direct oncogenic activities of different HCV proteins in vitro, in mouse models in vivo, these data are contradictory, whereas data on the tumor promoting effect of HCV proteins are much more consistent [10], [23], [48]. Our data suggest that the selected Mdr2-KO mouse model was appropriate for this specific investigation aimed to determine which of the potential different factors contributed mainly to HCC development with special emphasis on the inflammatory process in the Mdr2-KO mice lacking the HCV transgene as its main contribution to the model. The role of specific factors contributing to tumor promoting activity of the HCV transgene: sex, known genes that differ between the two studied mouse strains, and differentially expressed regulatory genes revealed by our gene expression profiling analysis requires further investigation.

Supporting Information

Scheme of the breeding of B6/HCV and Mdr2-KO mice to generate Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice.

(1.53 MB TIF)

The effect of Mdr2-KO, HCV-Tg and tumor phenotype on differential gene expression between experimental groups. The result of the SPIN analysis performed on 1,000 genes with the highest standard deviation. The left panel displays the color-coded standardized Euclidean distance matrix of samples and the right panel - the expression matrix of genes. Similar to hierarchical clustering (Figure 4), clustering was determined mainly by the Mdr2 genotype and the tumor phenotype, whereas the contribution of the HCV transgene was only marginal.

(3.16 MB TIF)

The effect of Mdr2-KO, HCV-Tg, and tumor phenotype on alternative splicing. Numbers before slash represent the amount of probe-sets with 2-fold or 1.8-fold change in the relative level of exon inclusion, determined as statistically significant by either paired t-test (for tumors versus non-tumorous tissues), or two-way ANOVA (for all other categories). Numbers after slash represent the amount of unique genes represented by the selected probe-sets. * The data for alternative splicing in tumors could not be directly compared with other categories due to the use of a different method of calculation.

(0.03 MB DOC)

Substantial overlapping of pathways affected by the HCV transgene and by the Mdr2-KO mutation. The SPIN analysis of the complete set of samples performed in the space of the 1,000 most variable genes resulted in separation of the samples into 3 groups: non-tumorous Mdr2-KO, Mdr2(+/−), and tumorous Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg samples (Fig. S2, left). The non-tumorous Mdr2-KO set was roughly separated into Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg and Mdr2-KO subsets. The SPIN analysis of the selected gene-set in the space of all Mdr2-KO samples enabled isolation of genes with tendency to differential expression between HCV-Tg and non-HCV samples. The lists of genes with tendency to up- and down-regulation in Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg samples were submitted to functional analysis by GO categories using the DAVID tool. These results were compared to the results of functional analysis by GO categories of genes differentially expressed between Mdr2-KO and Mdr2(+/−) non-HCV samples (threshold 1.85). For each enriched GO term, the number of related genes, their percent in the analyzed gene list and the significance of the enrichment are shown.

(0.03 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. La Monica (IRBM, “P. Angeletti”, Italy) for providing the HCV-transgenic mice, Amos Grundwag (Eisenberg Bros. Ltd, Israel) for assistance with bioinformatics, Dr. T. Ben-Moshe (Protalix Biotherapeutics, Israel) for help with immunohistochemistry, and our colleagues from the Goldyne Savad Institute of Gene Therapy, Carol Levy and Mery Clausen for their assistance in work with mice, and manuscript preparation, respectively.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: E.G. is supported by the EC grants LSHB-CT-2004-512034 (MOLEDA) and LSHB-CT-2005-018961 (INTHER), and by grants from the Barbara Fox, the Harold Grinspoon, the Horowitz and the Wolfson Foundations. E.G. holds the Sam and Ellie Fishman Chair in Gene Therapy. D.G. is supported by the Kamea Scientific Foundation of the Israeli Government. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ, McGlynn KA. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(10):817–823. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang TJ, Heller T. Pathogenesis of hepatitis C-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S62–71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, et al. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317(5834):121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu MC, Yuan JM. Environmental factors and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farazi PA, Depinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moriya K, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Tsutsumi T, et al. The core protein of hepatitis C virus induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice. Nat Med. 1998;4(9):1065–1067. doi: 10.1038/2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerat H, Honda M, Beard MR, Loesch K, Sun J, et al. Steatosis and liver cancer in transgenic mice expressing the structural and nonstructural proteins of hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(2):352–365. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naas T, Ghorbani M, Alvarez-Maya I, Lapner M, Kothary R, et al. Characterization of liver histopathology in a transgenic mouse model expressing genotype 1a hepatitis C virus core and envelope proteins 1 and 2. J Gen Virol. 2005;86(Pt 8):2185–2196. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonzi T, Agrati C, Costabile B, Cicchini C, Amicone L, et al. Steatosis and intrahepatic lymphocyte recruitment in hepatitis C virus transgenic mice. J Gen Virol. 2004;85(Pt 6):1509–1520. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19724-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furutani T, Hino K, Okuda M, Gondo T, Nishina S, et al. Hepatic iron overload induces hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis C virus polyprotein. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(7):2087–2098. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mauad TH, van Nieuwkerk CM, Dingemans KP, Smit JJ, Schinkel AH, et al. Mice with homozygous disruption of the mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene. A novel animal model for studies of nonsuppurative inflammatory cholangitis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1994;145(5):1237–1245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamoto Y, Guidotti LG, Kuhlen CV, Fowler P, Chisari FV. Immune pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Med. 1998;188(2):341–350. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang F, Huang X, Yi T, Yen Y, Moore DD, et al. Spontaneous development of liver tumors in the absence of the bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):863–867. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, Abramovitch R, Amit S, et al. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431(7007):461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzenellenbogen M, Pappo O, Barash H, Klopstock N, Mizrahi L, et al. Multiple adaptive mechanisms to chronic liver disease revealed at early stages of liver carcinogenesis in the Mdr2-knockout mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4001–4010. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakurai T, Maeda S, Chang L, Karin M. Loss of hepatic NF-kappa B activity enhances chemical hepatocarcinogenesis through sustained c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(28):10544–10551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603499103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagen TM, Huang S, Curnutte J, Fowler P, Martinez V, et al. Extensive oxidative DNA damage in hepatocytes of transgenic mice with chronic active hepatitis destined to develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(26):12808–12812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katzenellenbogen M, Mizrahi L, Pappo O, Klopstock N, Olam D, et al. Molecular mechanisms of liver carcinogenesis in the Mdr2-knockout mice. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(11):1159–1170. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Michael Eisen Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and University of California, Berkeley; http://rana.lbl.gov/EisenSoftware.htm.

- 20.Tsafrir D, Tsafrir I, Ein-Dor L, Zuk O, Notterman DA, et al. Sorting points into neighborhoods (SPIN): data analysis and visualization by ordering distance matrices. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(10):2301–2308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Affymetrix technical note. Identifying and validating alternative splicing events.

- 22.Okamoto M, Utsunomiya T, Wakiyama S, Hashimoto M, Fukuzawa K, et al. Specific gene-expression profiles of noncancerous liver tissue predict the risk for multicentric occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus-positive patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(7):947–954. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsutsumi T, Suzuki T, Moriya K, Shintani Y, Fujie H, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein activates ERK and p38 MAPK in cooperation with ethanol in transgenic mice. Hepatology. 2003;38(4):820–828. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wurmbach E, Chen YB, Khitrov G, Zhang W, Roayaie S, et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45(4):938–947. doi: 10.1002/hep.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita T, Kaneko S, Hashimoto S, Sato T, Nagai S, et al. Serial analysis of gene expression in chronic hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282(2):647–654. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camby I, Le Mercier M, Lefranc F, Kiss R. Galectin-1: a small protein with major functions. Glycobiology. 2006;16(11):137R–157R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CG, Ren J, Cheong IS, Ban KH, Ooi LL, et al. Expression of the FAT10 gene is highly upregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and other gastrointestinal and gynecological cancers. Oncogene. 2003;22(17):2592–2603. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang H, Fujii H, Sankila A, Mahler-Araujo BM, Matsuda M, et al. Beta-catenin mutations are frequent in human hepatocellular carcinomas associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(6):1795–1801. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65496-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machida K, Cheng KT, Sung VM, Shimodaira S, Lindsay KL, et al. Hepatitis C virus induces a mutator phenotype: enhanced mutations of immunoglobulin and protooncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(12):4262–4267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303971101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall A, Rushbrook S, Davies SE, Morris LS, Scott IS, et al. Relation between hepatocyte G1 arrest, impaired hepatic regeneration, and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):33–42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith MW, Yue ZN, Korth MJ, Do HA, Boix L, et al. Hepatitis C virus and liver disease: global transcriptional profiling and identification of potential markers. Hepatology. 2003;38(6):1458–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shackel NA, McGuinness PH, Abbott CA, Gorrell MD, McCaughan GW. Insights into the pathobiology of hepatitis C virus-associated cirrhosis: analysis of intrahepatic differential gene expression. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(2):641–654. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64884-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freund R, Dubensky T, Bronson R, Sotnikov A, Carroll J, et al. Polyoma tumorigenesis in mice: evidence for dominant resistance and dominant susceptibility genes of the host. Virology. 1992;191(2):724–731. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90248-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davie SA, Maglione JE, Manner CK, Young D, Cardiff RD, et al. Effects of FVB/NJ and C57Bl/6J strain backgrounds on mammary tumor phenotype in inducible nitric oxide synthase deficient mice. Transgenic Res. 2007;16(2):193–201. doi: 10.1007/s11248-006-9056-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lifsted T, Le Voyer T, Williams M, Muller W, Klein-Szanto A, et al. Identification of inbred mouse strains harboring genetic modifiers of mammary tumor age of onset and metastatic progression. Int J Cancer. 1998;77(4):640–644. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980812)77:4<640::aid-ijc26>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wakabayashi Y, Mao JH, Brown K, Girardi M, Balmain A. Promotion of Hras-induced squamous carcinomas by a polymorphic variant of the Patched gene in FVB mice. Nature. 2007;445(7129):761–765. doi: 10.1038/nature05489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marden JJ, Harraz MM, Williams AJ, Nelson K, Luo M, et al. Redox modifier genes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(10):2913–2919. doi: 10.1172/JCI31265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu DC, Re DB, Nagai M, Ischiropoulos H, Przedborski S. The inflammatory NADPH oxidase enzyme modulates motor neuron degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(32):12132–12137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603670103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362(9399):1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu SN, Su WW, Yang SS, Chang TT, Cheng KS, et al. Secular trends and geographic variations of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(8):1946–1952. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amin J, Dore GJ, O'Connell DL, Bartlett M, Tracey E, et al. Cancer incidence in people with hepatitis B or C infection: a large community-based linkage study. J Hepatol. 2006;45(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katzenellenbogen M, Mizrahi L, Pappo O, Klopstock N, Olam D, et al. Molecular mechanisms of the chemopreventive effect on hepatocellular carcinoma development in Mdr2 knockout mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(4):1283–1291. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang W, Lazaro CA, Campbell JS, Parks WT, Katze MG, et al. Responses of nontransformed human hepatocytes to conditional expression of full-length hepatitis C virus open reading frame. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(6):1831–1846. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bursch W, Grasl-Kraupp B, Wastl U, Hufnagl K, Chabicovsky M, et al. Role of apoptosis for mouse liver growth regulation and tumor promotion: comparative analysis of mice with high (C3H/He) and low (C57Bl/6J) cancer susceptibility. Toxicol Lett. 2004;149(1–3):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gale M, Jr, Foy EM. Evasion of intracellular host defence by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;436(7053):939–945. doi: 10.1038/nature04078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blindenbacher A, Duong FH, Hunziker L, Stutvoet ST, Wang X, et al. Expression of hepatitis c virus proteins inhibits interferon alpha signaling in the liver of transgenic mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(5):1465–1475. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Markiewski MM, Lambris JD. The role of complement in inflammatory diseases from behind the scenes into the spotlight. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(3):715–727. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamegaya Y, Hiasa Y, Zukerberg L, Fowler N, Blackard JT, et al. Hepatitis C virus acts as a tumor accelerator by blocking apoptosis in a mouse model of hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2005;41(3):660–667. doi: 10.1002/hep.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.(2008) Mouse Genome Informatics database (Jackson Laboratory) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Starr A, Greif J, Vexler A, Ashkenazy-Voghera M, Gladesh V, et al. ErbB4 increases the proliferation potential of human lung cancer cells and its blockage can be used as a target for anti-cancer therapy. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(2):269–274. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abid MR, Yi X, Yano K, Shih SC, Aird WC. Vascular endocan is preferentially expressed in tumor endothelium. Microvasc Res. 2006;72(3):136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Avila MA, Berasain C, Torres L, Martin-Duce A, Corrales FJ, et al. Reduced mRNA abundance of the main enzymes involved in methionine metabolism in human liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2000;33(6):907–914. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Damdinsuren B, Nagano H, Kondo M, Yamamoto H, Hiraoka N, et al. Expression of Id proteins in human hepatocellular carcinoma: relevance to tumor dedifferentiation. Int J Oncol. 2005;26(2):319–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vietor I, Huber LA. Role of TIS7 family of transcriptional regulators in differentiation and regeneration. Differentiation. 2007;75(9):891–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan X, Chua MS, Sun H, So S. N-Myc down-regulated gene 1 mediates proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;262(1):133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim J, Yang P, Suraokar M, Sabichi AL, Llansa ND, et al. Suppression of prostate tumor cell growth by stromal cell prostaglandin D synthase-derived products. Cancer Res. 2005;65(14):6189–6198. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahn SG, Kim HS, Jeong SW, Kim BE, Rhim H, et al. Sox-4 is a positive regulator of Hep3B and HepG2 cells' apoptosis induced by prostaglandin (PG)A(2) and delta(12)-PGJ(2). Exp Mol Med. 2002;34(3):243–249. doi: 10.1038/emm.2002.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu L, Yu XZ, Li TS, Song LX, Chen PL, et al. A novel protein tyrosine kinase NOK that shares homology with platelet- derived growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptors induces tumorigenesis and metastasis in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64(10):3491–3499. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kurt-Jones EA, Cao L, Sandor F, Rogers AB, Whary MT, et al. Trefoil family factor 2 is expressed in murine gastric and immune cells and controls both gastrointestinal inflammation and systemic immune responses. Infect Immun. 2007;75(1):471–480. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02039-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ren J, Kan A, Leong SH, Ooi LL, Jeang KT, et al. FAT10 plays a role in the regulation of chromosomal stability. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(16):11413–11421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berruyer C, Martin FM, Castellano R, Macone A, Malergue F, et al. Vanin-1−/− mice exhibit a glutathione-mediated tissue resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(16):7214–7224. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7214-7224.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Scheme of the breeding of B6/HCV and Mdr2-KO mice to generate Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg mice.

(1.53 MB TIF)

The effect of Mdr2-KO, HCV-Tg and tumor phenotype on differential gene expression between experimental groups. The result of the SPIN analysis performed on 1,000 genes with the highest standard deviation. The left panel displays the color-coded standardized Euclidean distance matrix of samples and the right panel - the expression matrix of genes. Similar to hierarchical clustering (Figure 4), clustering was determined mainly by the Mdr2 genotype and the tumor phenotype, whereas the contribution of the HCV transgene was only marginal.

(3.16 MB TIF)

The effect of Mdr2-KO, HCV-Tg, and tumor phenotype on alternative splicing. Numbers before slash represent the amount of probe-sets with 2-fold or 1.8-fold change in the relative level of exon inclusion, determined as statistically significant by either paired t-test (for tumors versus non-tumorous tissues), or two-way ANOVA (for all other categories). Numbers after slash represent the amount of unique genes represented by the selected probe-sets. * The data for alternative splicing in tumors could not be directly compared with other categories due to the use of a different method of calculation.

(0.03 MB DOC)

Substantial overlapping of pathways affected by the HCV transgene and by the Mdr2-KO mutation. The SPIN analysis of the complete set of samples performed in the space of the 1,000 most variable genes resulted in separation of the samples into 3 groups: non-tumorous Mdr2-KO, Mdr2(+/−), and tumorous Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg samples (Fig. S2, left). The non-tumorous Mdr2-KO set was roughly separated into Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg and Mdr2-KO subsets. The SPIN analysis of the selected gene-set in the space of all Mdr2-KO samples enabled isolation of genes with tendency to differential expression between HCV-Tg and non-HCV samples. The lists of genes with tendency to up- and down-regulation in Mdr2-KO/HCV-Tg samples were submitted to functional analysis by GO categories using the DAVID tool. These results were compared to the results of functional analysis by GO categories of genes differentially expressed between Mdr2-KO and Mdr2(+/−) non-HCV samples (threshold 1.85). For each enriched GO term, the number of related genes, their percent in the analyzed gene list and the significance of the enrichment are shown.

(0.03 MB DOC)