Abstract

Non-invasive monitoring of tissue-engineered constructs is an important component in optimizing construct design and assessing therapeutic efficacy. In recent years, cellular and molecular imaging initiatives have spurred the use of iron oxide based contrast agents in the field of NMR imaging. Although their use in medical research has been widespread, their application in tissue engineering has been limited. In this study, the utility of Monocrystalline Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (MION) as an NMR contrast agent was evaluated for βTC-tet cells encapsulated within alginate/poly-L-lysine/alginate (APA) microbeads. The constructs were labeled with MION in two different ways: (a) MION-labeled βTC-tet cells were encapsulated in APA beads (i.e., intracellular compartment); and (b) MION particles were suspended in the alginate solution prior to encapsulation so that the alginate matrix was labeled with MION instead of the cells (i.e., extracellular compartment). The data show that although the location of cells can be identified within APA beads, cell growth or rearrangement within these constructs cannot be effectively monitored, regardless of the location of MION compartmentalization. The advantages and disadvantages of these techniques and their potential use in tissue engineering are discussed.

Keywords: MION, βTC-tet, alginate, tissue engineering

Introduction

Non-invasive monitoring of tissue-engineered constructs is important toward optimizing design and assessing therapeutic efficacy. Several imaging modalities have been applied to monitor tissue-engineered constructs in vitro or in vivo: optical [1, 2], radionuclide [3], computed tomography (CT) [4, 5] and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [6–11]. Each method offers advantages and disadvantages. Optical techniques are highly sensitive, generate images with subcellular resolution, but require genetic manipulation of cells and have limited in vivo capabilities due to limited light transmission through tissues. Radionuclide techniques are also highly sensitive, but require administration of radioactive agents and suffer from low spatial resolution. CT offers structural information, but does not provide metabolic information. NMR offers a distinct advantage relative to other modalities because it provides structural information through imaging techniques and metabolic information through spectroscopic techniques from the same tissue-engineered construct. However, NMR techniques suffer from inherent low sensitivity. To enhance sensitivity, paramagnetic and superparamagnetic contrast agents have been developed to alter NMR properties of the cell/tissue with which they interact.

Recently, cellular and molecular imaging initiatives have spurred the use of iron oxide-based contrast agents in NMR imaging [12], specifically small paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles. These commercially available agents affect T1, T2 or T2* relaxation times. Ultra-small paramagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles have diameters less than 40 nm [13, 14], while the superparamagnetic monocrystalline iron oxide nanoparticles (MION) are comprised of a monocrystalline core of 4–6 nm and coated with dextran or other polymer. Cells uptake MION nanoparticles in culture, and because of MION’s superparamagnetic properties, NMR imaging techniques track the in vivo location of MION-labeled cells after implantation. This technique has been used successfully to follow various cells in vivo: lymphocytes [15], cancer cells [16], islets [17, 18], muscle stem cells [19] and others (Gupta and Gupta provide a thorough review on the use of these nanoparticles in biomedical applications [20]). In the context of tissue engineering, nanoparticle use as a contrast agent has been limited [21], although they have been used to generate three-dimensional constructs without scaffolds by guiding magnetically labeled cells to specific locations via a magnetic field [21–24]. Terrovitis et al. [21] utilized commercially available SPIO particles (Feridex™) to label mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) that were subsequently either embedded in a collagen gel construct or contained within a collagen scaffold. The constructs were monitored by MRI for four weeks, and the authors concluded that labeling MSCs with Feridex™ was an effective, non-invasive, non-toxic technique to track tissue-engineered constructs using MRI.

The present study investigates the utility of MION as an MRI contrast agent for a model tissue-engineered pancreatic construct, with the intent to monitor this construct after implantation and monitor growth and subsequent cell rearrangement within the construct. This model is composed of insulin secreting cells (murine insulinoma βTC-tet cells) encapsulated in alginate/poly-L-lysine/alginate (APA) microbeads. Constructs were labeled with MION by either: (a) labeling βTC-tet cells with MION prior to encapsulation within APA beads; or (b) suspending MION in the alginate solution prior to encapsulation so that the alginate matrix was MION-labeled instead of the cells. The advantages and disadvantages of these approaches and the potential of magnetic nanoparticles as MRI contrast agents in tissue engineering are discussed.

Methods

Cell line

Murine insulinoma βTC-tet cells were cultivated as monolayers in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) containing 20 mM glucose and supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 ng/ml streptomycin), and 6 mM L-glutamine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cultures were maintained at 37°C under humidified (5% CO2/95% air) conditions. βTC-tet cells integrate a bacterial tetracycline (tet) operon system regulating expression of a proliferation oncogene (SV40 large T antigen) such that the presence of tetracycline (TC) shuts down oncogene production, suppressing cell growth [25].

Cell Entrapment

βTC-tet cells were entrapped at a density of 3.5 ×107 cells/ml alginate in 2% w/v alginate beads using protocols developed by Lim and Sun [26, 27], and used by us [28, 29]. The alginate (NovaMatrix, Oslo, Norway) had low viscosity (325 mPa) and high (62%) mannuronic acid content. Beads with 500±50 μm diameters were created using an electrostatic bead generator (Nisco, Zurich, Switzerland) and cross-linked by dropping beads into 100 mM CaCl2. Gelled beads were subsequently coated with poly-L-lysine (PLL) (MW=19,200 g/mole, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and an additional layer of alginate (0.2% w/v alginate) to form alginate/poly-L-lysine/alginate (APA) beads [30].

Aliquots of APA beads (2–3 ml) were transferred to T-75 flasks (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) containing 25 ml of fully supplemented DMEM and placed on a platform rocker (Stovall Life Sciences, Greensboro, NC) within a 37°C humidified, gas-regulated (5% CO2/95% air) incubator. APA cultures were maintained in fully supplemented DMEM and fed every 2–3 days. Growth suppressed encapsulated cultures were fed every 2–3 days with fully supplemented media containing 30 ng/ml tetracycline (TC).

Monocrystalline iron oxide nanoparticles (MION)

MION were prepared using previously published protocols [31]. A solution of FeCl2 and FeCl3 was titrated with 0.5 M NaOH with vigorous stirring to yield a magnetite precipitate, Fe3O4. The precipitate was collected via centrifugation and neutralized with 0.2 M HCl. Cationic colloidal nanoparticles were separated by centrifugation, diluted and stabilized using 1 M sodium citrate solution. The MION solution was adjusted to pH 7 by dialysis against a large volume of 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer. Particle size was determined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and shown to have a core size of approximately 4 nm, as in our previous study [31]. The iron concentration of the MION stock solution was 666.64 mg/ml, determined either by inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (ICP) or spectrophotometrically, as previously described [31].

MION effects on APA bead constructs were assessed by: (i) labeling βTC-tet cells with MION prior to cell encapsulation; and (ii) dispersing MION particles in the alginate solution and using this labeled alginate to encapsulate un-labeled βTC-tet cells. The fundamental difference between these two experiments is the nanoparticle location; MION particles are intracellular, or extracellular, respectively. Consequently, contrast generated in the former represents cells; in the latter the alginate matrix. To label cells, monolayer cultures were incubated in media containing MION (250 μl of stock solution in 20 ml of DMEM) overnight (~20 hours). After incubation, cells were trypsinized, suspended in 2% w/v alginate and encapsulated in APA beads. To generate labeled alginate, 62.5 μl of stock MION solution were mixed with 5 ml of a 2% alginate solution prior to the suspension and encapsulation of cells.

MR imaging

MR data were acquired using a vertical 17.6-T, 89-mm bore magnet equipped with a Bruker Avance console and Micro2.5 gradients (maximum strength of 1000 mT/m). Beads were immersed in DMEM and loaded into a capillary (outer/inner diameter of 700/530 μm). The capillary was placed within a homebuilt solenoidal radiofrequency (RF) microcoil 850 μm in diameter. The small RF solenoid, susceptibility-matched to reduce field perturbations, greatly improves the sensitivity of the MR experiment [32]. Several beads were analyzed simultaneously and examined without perfusion to avoid motion artifacts.

High resolution images were obtained using spin echo (SE) and gradient recalled echo (GRE) sequences to develop diffusion-, T2- and T2*-weighted contrast and quantify relevant MR parameters. A modified multi-slice two-dimensional (2D) SE sequence with balanced bipolar gradients acquired microimages with and without diffusion weighting. With a total acquisition time of approximately 1.1 hours, T2 and diffusion images were acquired at an in-plane resolution of 25×25 μm and slice thickness of 100 μm with a repetition time (TR) of 2.5 s. To quantify T2, the SE sequence was acquired individually at multiple echo times (TE) ranging between 12.5–75.5 ms, NEX=4 and a bandwidth of 73 kHz. Diffusion-weighted images were acquired by incrementing the b value from 186–7,000 s/mm2 (TE/TR=25.5/2,500 ms and NEX=36) to measure the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC). T2* relaxation was assessed using a 2D multi-slice GRE sequence, which was acquired individually with a TE incremented between 6–26 ms (tip angle = 90°, NEX = 4, BW = 50 kHz and TR = 1 s). True three-dimensional (3D) high resolution GRE images also were acquired at an isotropic resolution of 20 mm using a 22° tip angle.

Quantitative MR image analysis to determine T2, T2* and ADC was performed in a region of interest (ROI) encompassing the entire alginate bead. For each ROI, mean signal intensity and the standard deviation of signal intensity was determined. A full bead ROI approach was chosen for two reasons. First, differences in intra-bead regions are only evident at later growth stages; a segmented bead analysis would have required post hoc analysis that would differ for each culture time point, contrast mechanism and label with MION. Given the consistent bead diameter through the culture period, full bead ROI analysis provides a measure independent of intra-bead changes. Second, although this work focuses on in vitro cultures, future in vivo measures conducted post-implantation would be limited to full bead ROI analysis at best, given currently available pre-clinical resolutions. For all measurements (diffusion, T2 and T2*), mean signal data from each ROI were fit to a single decaying exponential function using a Levenberg-Marquardt nonlinear least squares regression [33]. Samples were imaged five times during a 30-day culture of the encapsulated βTC-tet cells. During each imaging session, at least four beads in each sample were assessed via ROI analysis, and beads were disposed (i.e.,not returned to culture) after imaging.

Glucose Stimulate Insulin Secretion (GSIS)

On the day of entrapment (day 0) and day 27 following entrapment, the amount of insulin released as a function of step changes in glucose concentration was determined. Entrapped cultures were washed in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Mediatech, Herndon, VA), then incubated in DPBS for 1.5 hours to normalize all cultures to the same initial conditions prior to secretion experiments. DPBS was removed, and cultures were exposed serially (for 20 minutes each) to: serum-free media containing no glucose; fully-supplemented DMEM containing 3 mM glucose; and fully-supplemented DMEM containing 20 mM glucose. Between every glucose concentration step, beads were washed and incubated in DPBS for 1.5 hours. Media samples were taken at the beginning and end of each episode to determine the amount of insulin released into the media. Insulin levels were measured by an ELISA kit (Linco, St. Charles, MO), read on a Synergy HT plate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT). Values of insulin released by entrapped cells are normalized to 105 cells at the time of entrapment.

Glucose Consumption

Culture media samples were collected from each flask immediately after every feeding and 24 hours later. Glucose levels were measured on a Vitros DT60II bioanalyzer (Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY). Glucose consumption rates (GCR) were calculated and normalized to 105 cells at the time of entrapment. GCR was assessed at least every four days during the course of the cultures.

Histology

APA beads were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis. MO) in Tyrode’s Buffer (pH 7.2). After fixation (4h), beads were rinsed in 70% ethanol, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, sliced and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Digital photomicrographs were taken using a 10× objective (Nikon, Japan).

Statistical Methods

Data in GCR time curves are presented as means ± SD of multiple measurements derived from three independently encapsulated cultures. At least two samples were measured per encapsulation. For GSIS studies, insulin release data are presented as means ± SD based on two measurements from a single encapsulation. Statistical comparisons were performed by a Student’s t-test.

Results

The main objective of this study is to utilize MION as an MRI contrast agent to monitor temporal changes in growth and rearrangement of cells encapsulated in APA microbeads. To interpret temporal changes in MR images, it is necessary to first characterize the relationships between the: (a) T2 and T2* relaxation times and iron content; (b) cell number and intracellular iron content; (c) APA bead volume and iron content; and (d) volume of APA beads that contain a fixed density of MION-labeled βTC-tet cells and iron content. The relaxivity of MION-labeling at 17.6 T was quantified by imaging alginate beads (cell-free) containing a known amount of MION. Cell-free blank alginate beads were generated by mixing different aliquots of the MION stock solution with 2% w/v solution of LVG alginate. Figure 1A demonstrates the effect that superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles have on T2 and T2* relaxation times. Specifically, as iron content increased from 0.625 mg/ml in alginate beads, T2 and T2* relaxations decreased exponentially, reaching a minimum between 5–10 mg iron/ml alginate. The relationship between intracellular iron content and the number of cells exposed to MION was linear, at least for cell numbers up to 1.4 × 108 cells, as depicted in Figure 1B, with a per cell content of approximately 35 pg MION/cell. Similar linear correlations also were observed for the relationships between iron content and the volume of MION blank APA beads (Figure 1C) and iron content and volume of APA beads that contain MION-labeled βTC-tet cells (Figure 1D). These linearities in Fig.1 Panels B, C and D are not unexpected, but aid in characterizing the effect of MION concentration on MR relaxation and establish a MION concentration required to elicit an identifiable MR contrast.

FIGURE 1.

Graphs displaying the correlation between: (A) T2 and T2* relaxation times and amount of iron oxide (in mg/ml) in cell-free APA beads; (B) the amount of iron and the number of MION-labeled βTC-tet cells; (C) the amount of iron and the volume of cell-free APA beads labeled with MION; and (D) the amount of iron and the volume of APA beads that contained MION-labeled βTC-tet cells at a cell density of 3.5×107 cells/ml alginate.

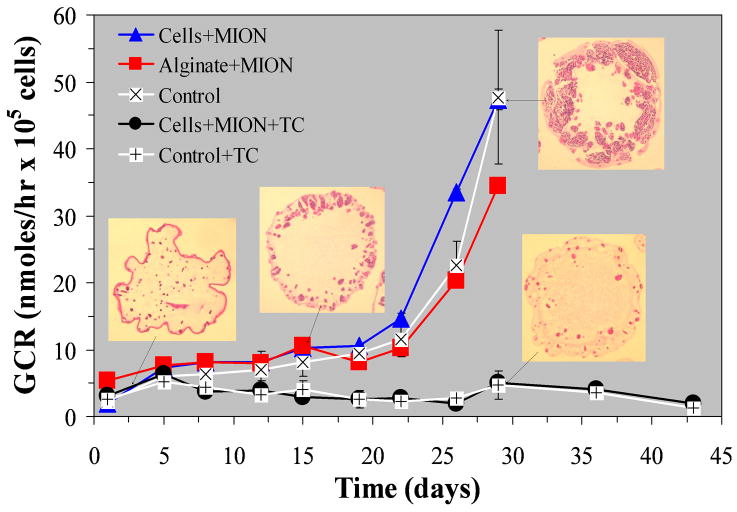

A previous study reported that exposing βTC-tet cells to MION-containing media for 24 hrs did not affect either cellular glucose consumption or insulin secretion [31]. That conclusion was based on measurements performed immediately after MION exposure. The present study extends these measurements to long-term cultures of APA encapsulated βTC-tet cells. Figure 2 shows temporal profiles of glucose consumption rates by encapsulated βTC-tet cells as a function of MION labeling location and growth regulation. Also depicted are representative 5 μm cross-sections of APA beads stained with Hematoxylin/Eosin. The data show that APA-encapsulated βTC-tet cells cultured in the absence of tetracycline displayed a glucose consumption increase due to continuous cellular proliferation, while APA beads cultured in the presence of tetracycline maintained their initial metabolic activity for the experiment duration because cell proliferation was suppressed. These dynamics of regulated and unregulated growth of βTC-tet cells are consistent with previously published data [34, 35]. These data also demonstrate that labeling these model tissue-engineered constructs either in the extracellular alginate matrix or in the cells did not affect the gross metabolic activity of encapsulated cells.

FIGURE 2.

Temporal profiles of glucose consumption rates (GCR) by βTC-tet cells encapsulated in APA beads composed of 2% w/v MVM alginate and cultured either in the absence or in the presence of 30 ng/ml tetracycline (TC). Five groups of APA cultures are depicted in the graph. GCR measurements from cultures that were not labeled with MION (i.e., Control) are depicted either by white squares with a black × for non-TC treated cultures, or by white squares with a black + for TC treated cultures. Measurements from MION-labeled cells encapsulated in APA beads and cultured in the absence of TC are depicted by triangles, while measurements from MION-labeled cells encapsulated in APA beads and cultured in the presence of TC are depicted by circles. Finally, measurements from APA beads made with MION-labeled alginate are depicted by squares. Representative histology cross-sections from beads cultured in the absence and presence of TC are shown to illustrate the effect of TC to regulate growth.

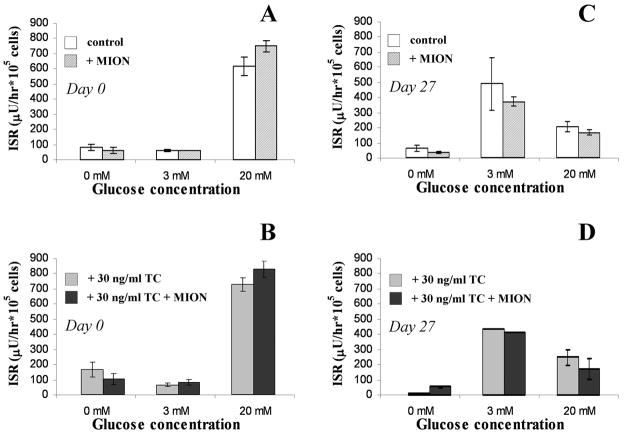

Insulin release measurements were made following step changes from 0 to 3 to 20 mM glucose performed within a day of encapsulation and 27 days later (Figure 3). For unregulated and growth-regulated cell cultures at Day 0 (Panels 3A and 3B, respectively), MION presence did not affect insulin release. The cells exhibited a secretory response to high glucose (20 mM) but not 0 or 3 mM glucose media. After 27 days of culture, the insulin release profile differed from Day 0, but this release was not affected by MION presence. The change in glucose responsiveness following culture (i.e., cultures releasing insulin when exposed to 3 mM glucose) may be due to genetic drift, but this change is not MION dependent. Additionally, the reduction of insulin release at 20 mM glucose compared to the 3 mM stimulated release observed in Day 27 cultures may be attributed to an insufficient time for cells to regenerate insulin stores, as release studies were done serially, from low glucose to high. Regardless, these data show that MION labeling did not affect cellular secretory activity. Thus, MION labeling is not detrimental to: (a) cell growth as illustrated by histology; (b) metabolic activity of encapsulated cells as depicted by temporal changes in GCR; or (c) secretory activity of encapsulated cells.

FIGURE 3.

The effect of intracellular MION labeling on the insulin release of βTC-tet cells encapsulated in 2% w/v MVM APA beads and cultured either in the absence or in the presence of 30 ng/ml tetracycline (TC). Insulin release following step changes from 0 to 3 to 20 mM glucose is shown for: (A) control (i.e., no TC) unlabeled vs. MION labeled cells at Day 0; (B) TC-treated unlabeled vs. TC-treated and MION labeled cells at Day 0; (C) control (no TC) unlabeled vs. MION labeled cells at Day 27; (D) TC-treated unlabeled vs. TC-treated and MION labeled cells at Day 27. Each bar represents the mean insulin released and the error bars represent the s.d. of the means based on duplicate measurements from a single encapsulation.

MR images were acquired weekly from various encapsulated cultures. Figure 4 displays 2D SE T2- (T2W), diffusion- (DW) and T2*-weighted (T2*W) images as well as 3D GRE images acquired 1, 13 and 27 days post-encapsulation from cultures not treated with tetracycline (unregulated growth). Panel A shows images acquired from control, non-MION labeled, APA beads; Panel B depicts images acquired from APA beads generated with MION-labeled βTC-tet cells; and Panel C shows images acquired from APA beads generated with MION suspended in the alginate gel. Image inspection illustrates marked differences between the three different APA populations. Furthermore, marked differences are observed between the types of contrast imaging performed (T2 vs. T2* vs. diffusion vs. 3D GRE). Specifically, MR images acquired from MION-free APA beads (Figure 4A) within a day of encapsulation display beads without readily discernible structures (i.e., cells). As histology cross sections demonstrate in Figure 2, immediately post-encapsulation, cells are distributed uniformly throughout the beads. Thus, it is reasonable that images acquired with an in-plane resolution of 25×25 μm and slice thickness of 100 μm cannot readily distinguish single cells (approximate cell diameter 10 μm). However, as encapsulated βTC-tet cells proliferate unhindered in low-viscosity high mannuronic content alginate beads, they rearrange to form an O-ring at the periphery of the APA beads, as we previously demonstrated [29, 34, 36], and show in Fig. 2. This pattern is clearly depicted on all MR images acquired at Day 27 regardless of the imaging contrast mechanism used. In T2W, T2*W, and 3D GRE images, this cellular ring is depicted by darker contrast (i.e., shorter T2). This contrast between ring and core is present because the core still contains a great deal of unpopulated alginate gel, which is 98% water. Moreover, by Day 27, cells that had initially occupied the central core die due to nutritional barriers imposed by the growing population on the outer ring. Conversely, in DW images, the outer ring has bright contrast due to restrictions to water diffusion both from intracellular compartmentalization and the high cellular density. Of the four image sequences employed in this study, only DW images clearly identified the developing cellular O-ring at Day 13 post encapsulation.

FIGURE 4.

T2-, T2*-, diffusion-weighted and 3D gradient echo (3DGE) MR images of: (A) control APA beads; (B) APA beads with MION-labeled βTC-tet cells; and (C) APA beads comprised of MION-labeled alginate but containing unlabeled βTC-tet cells. Images were obtained weekly for 4 weeks post encapsulation, but only Days 1, 13 and 27 are presented.

APA beads with MION-labeled βTC-tet cells (Figure 4B) yielded distinctly different patterns. The presence of superparamagnetic iron nanoparticles in cells allows for identification of cell location at the earliest time point post-encapsulation on all MR contrast mechanisms used in the study except for DW images. The images show black dots, attributed to MION-labeled cells, distributed throughout the beads. This pattern correlates with the histology cross-section displayed in Figure 2 for the same time point. Similar patterns of uniformly-distributed black dots also were observed in T2W, T2*W and 3D GRE images acquired at Day 13 and Day 27 post-encapsulation. This pattern does not corroborate with the cellular O-rings observed in the corresponding histology cross-sections shown in Figure 2; only DW images displayed the cellular O-ring pattern. This difference between histology cross-sections and MR images is attributable to the observed rearrangement due solely to processes of cell growth and death as a result of oxygen availability [37, 38] and not to active cell migration within the alginate matrix. Assuming cell growth and death processes do not cause large changes in the intra-bead MION density or distribution, cellular remodeling due to these processes may not change the gross particle distribution; cells that die in the bead center as a result of oxygen/nutrient starvation still display MION-related contrast in that location. Therefore, temporal changes in APA bead images are not observed. Conversely, active cell migration towards the periphery of the beads would have changed the intra-bead MION distribution, but such migration is not observed for this cell type in an unmodified alginate gel irrespective of the mannuronic and guluronic composition.

APA beads generated with MION dispersed within the extracellular alginate matrix (Figure 4C) presented MR images distinctly different than those seen in the previous two populations. Because superparamagnetic nanoparticles were uniformly distributed in the alginate gel, cells could not be identified in any MR images acquired at Day 1 post-encapsulation. Similarly, SE and GRE images acquired at Day 13 and Day 27 post-encapsulation did not exhibit specific cellular arrangement within beads. Only DW images acquired at Day 27 displayed the cellular O-ring pattern seen in the histology cross-section. At this time point, restrictive water diffusion becomes the dominant mechanism contributing to DW contrast, even though the presence of superparamagnetic particles affects ADC quantification.

MR images acquired from APA beads cultured under continuous tetracycline exposure to regulate the growth of encapsulated cells displayed similar patterns to those observed at Day 1 in Figure 4A and 4B (data not shown). In the presence of tetracycline, βTC-tet cells do not proliferate, thus maintained an almost steady cell population throughout the experiment (see histology cross-sections in Figure 2).

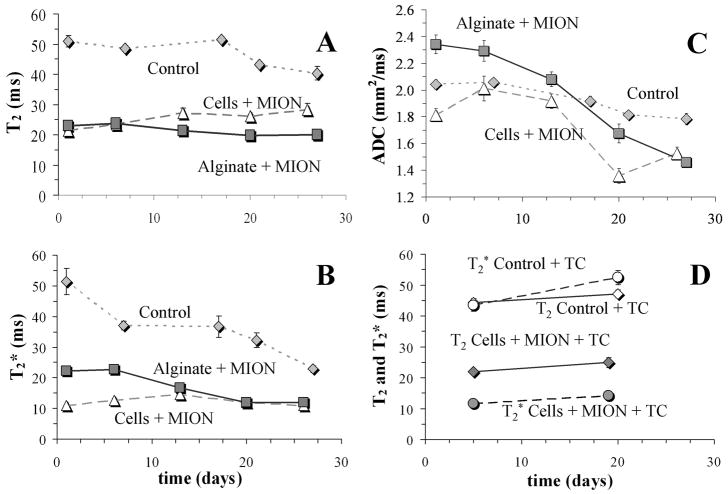

Image ROI analysis allowed quantitation of temporal changes in T2, T2* and ADC. Figure 5 displays the temporal profiles of T2, T2* and ADC for the three non-tetracycline treated APA populations, Panels A, B and C respectively, while Panel D shows temporal changes in T2 and T2* for the two tetracycline treated APA populations. Our data show that T2 and T2* relaxation times of water within APA beads was significantly higher in non-MION-labeled APA beads than in any APA bead MION preparation regardless of the label location (i.e., intracellular or extracellular). Not surprisingly, presence of superparamagnetic agent dominates the native relaxation mechanisms of beads, cells or the cellular growth pattern. This finding agrees with the calibration curve shown in Figure 1A, demonstrating that T2 and T2* relaxation times decrease with increasing MION content. The T2 values of MION-treated beads corroborate the amount of iron expected for the number of cells entrapped in the beads (between 1 and 2 mg/mL). For non-MION-labeled APA beads, uncontrolled growth over the experiment duration caused both T2 and T2* relaxation times to decrease, with more significant decreases evident in T2* relaxation. This finding is attributed to: (a) an increase in magnetic susceptibility; and (b) an increase in the fraction of water molecules in exchange with large macromolecular structures. Both of these result from an increased number of cells within the beads.

FIGURE 5.

Temporal changes in T2 (Panel A), T2* (Panel B) and ADC (Panel C) for non-TC treated cultures (control, white square with a black ×; MION-labeled cells, triangles; MION-labeled alginate, squares). Panel D shows temporal changes of T2 and T2* for TC treated bead preparations containing either unlabeled cells (Control) or MION-labeled cells.

When comparing APA beads containing MION-labeled cells to APA beads with MION dispersed in the alginate gel, we did not observe significant differences in T2 or T2* relaxation values. Furthermore, there were no significant temporal differences in either T2 or T2* in these cultures. This temporal stability agrees with similar measurements performed in collagen-based constructs by Terrovitis et al. [21]. Finally, there were no significant temporal differences in either T2 or T2* with growth-regulated (tetracycline treated) cultures. Several groups have investigated the relaxation effects of iron based contrast agents and their effects and distribution in heterogeneous biological tissues [39–43] and our results are interpreted considering these issues. Our observations suggest that either the nanoparticles contained within the APA beads are not reduced from the construct with time in culture regardless of their initial compartmentalization, or the quantity of nanoparticles encapsulated within the beads remains high enough to not affect these relaxation parameters. In contrast to the temporal stability displayed by both T2 and T2* relaxations in MION-labeled cultures, ADC measurements in the same APA cultures displayed a progressive decrease with cell growth (Panel C). Again, this decrease in ADC with culture time is attributed to the increased restrictive water diffusion imposed by cell growth, although it is notable that MION presence in the construct distorts the trend of ADC decrease compared to the control. This distortion is due to the presence, either in individual units internalized within cells or in a homogeneous distribution throughout the alginate, of iron particles that effectively produce an additional diffusion gradient field due to magnetic susceptibility, not accounted for in this analysis of water diffusion.

To address whether iron is lost from beads as a function of cell growth (i.e., a function of metabolic potential), ICP-Mass analysis of APA beads was performed at three time points during the month-long culture. Figure 6 shows temporal changes in intra-bead iron content as a function of tetracycline treatment from APA beads that contained MION-labeled βTC-tet cells. The data show that intra-bead iron content does not drop substantially over 19 days, corroborating the image stability seen in Fig. 4 and the T2 and T2* stability shown in Fig. 5. Additionally, there was no difference in the intra-bead iron content between APA beads cultured in the absence of tetracycline (i.e., unregulated growth) and APA beads cultured in the presence of tetracycline (i.e., regulated, thus no growth). These data suggest that any loss of iron from beads is not greatly influenced by cell proliferation, cell number or metabolic potential.

FIGURE 6.

Temporal changes in the intra-APA bead iron content determined by ICP as a function of TC induced growth suppression. White triangles depict measurements obtained from unsuppressed cultures (i.e., absence of TC). Black circles depict measurements obtained from TC growth-suppressed cultures (i.e., presence of TC in the culture media).

Discussion

MION and their derivatives have met considerable success in medical research as MRI contrast agents that provide investigators the ability to identify locations of individual cells post-implantation in vivo. Extending this success to tissue engineering applications, we initially reasoned that MION can: (a) mark the location of the construct in vivo; and (b) monitor temporal changes mediated by cell growth within the construct either in vitro or in vivo. Based on existing literature, there is little doubt that MION embedded within a construct can mark the location of the construct in vivo. Thus, our present study focused on exploring the second objective; the ability to monitor temporal changes mediated by cell growth within a construct. The ability to achieve this objective is critically important in optimizing the design of a tissue-engineered construct and maximizing its efficacy.

Data presented here show that the relationship between either T2 or T2* and iron content is exponential, reaching a minimum at concentrations above 5–10 mg/ml alginate. Furthermore, MION quantification in APA beads is stoichiometric, regardless of whether MION are placed in the intracellular or extracellular bead compartment. Although this information may appear obvious, it is important to characterize the system so that optimum relaxation effects can be attained with the minimum amount of MION, because large intracellular quantities of similar magnetic nanoparticles have been shown to affect islet insulin secretion [44]. In the present study, neither long-term growth nor secretory properties of encapsulated βTC-tet cells were affected at intracellular iron concentrations around 35 pg/cell. These data are an extension of a previous study performed on monolayer cultures of βTC-tet cells demonstrating no statistically significant effects on either metabolic or secretory indices immediately after MION exposure [31]. However, the iron content determined in Fig. 1D is approximately twice that expected for the cell numbers encapsulated. This may be attributable to a miscalculation of true bead volume, as beads can shrink when removed from media, thus yielding more beads (and MION) per volume than anticipated.

The study by Terrovitis et al. [21] demonstrated that use of iron oxide nanoparticles was an effective, non-invasive, and non-toxic technique to track a tissue-engineered construct using MRI. The present study agrees with this conclusion. However, this study provides additional new insight on the ability of nanoparticles to monitor growth-mediated cell rearrangement within an alginate based model tissue-engineered construct. Our data show that although MION-labeling cells within APA beads aids identifying the initial entrapped position, we could not exploit nanoparticles to monitor either cell growth or cell rearrangement within constructs better than what we can observe without MION (Fig. 4). This is true regardless of the location of MION compartmentalization (alginate labeled or cell labeled). This conclusion was reached because MR images obtained beyond the first few days post-encapsulation (once unregulated growth had commenced), did not correlate with histologic cross-sections of MR images acquired from sham-treated control cultures. This lack of correlation can be understood by considering that the superparamagnetic nanoparticles do not leave viable cells. Because it is known that the cells studied here cannot migrate within an alginate matrix, cellular rearrangement observed within our microbeads over time is due solely to the process of local cell growth and death as a result of nutrient availability. Because of this lack of migration, local superparamagnetic density and distribution within the APA beads does not readily change, though there may be a slight decrease in iron concentration over time. However, cell rearrangement observed in matrices that permit cell migration, such as collagen, may correlate with a particle distribution change. Under those conditions, it has been shown that use of superparamagnetic nanoparticles can facilitate the monitoring of cell growth and/or cell rearrangement within a tissue engineered construct [21].

Our data also demonstrate that T2 and T2* values were stable throughout the MION-labeling experiment (Figure 5A and 5B), corroborating the relative stability of the bead iron content over 19 days (Figure 6). This suggests that in this study, the amount of iron in the beads remains high enough to not affect either T2 or T2* relaxation times of the beads over the time course studied here. However, if sufficient iron content is lost, it reasons that by maintaining the cultures long-term, the intra-bead MION concentration may reach a level where both T2 and T2* values are affected, thus jeopardizing the long-term utility of this monitoring technique in tissue-engineered constructs unless encapsulated cells can be relabeled. Of the three contrast mechanisms utilized in this study, T2, T2* and diffusion, only DW images provided a representation of cell organization in MION-labeled beads, regardless of MION compartmentalization. It must be noted that MION presence altered the absolute values of the ADC and exaggerated the trend of ADC decrease with culture time compared to the unlabeled sample. Finally, our images also highlight the potential benefit of these nanoparticles. Specifically, when cells were labeled with MION and then encapsulated, MR images were capable of identifying the location of individual cells or an aggregate of a few cells. This identification was not possible when MION were dispersed within the alginate gel or in the absence of MION. Therefore, the premise that cells labeled with magnetic nanoparticles can be imaged by MR imaging techniques is also true in the context of tissue engineering, where labeled cells are encapsulated.

Conclusion

The data show that use of superparamagnetic nanoparticles, such as MION, to monitor longitudinal changes in cell growth and/or cell organization within alginate hydrogel based constructs is not better than using the native contrast of the construct. However, if the use of such nanoparticles is necessary to track the construct location, labeling cells rather than the gel is preferred because it allows the investigator to visualize the location of individual cells or cell clusters. Importantly, visualization of cells by MION labeling in this study came at the sacrifice of potentially critical quantitative data concerning the growth and metabolic status of cells within the construct.

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by the NIH (P41-RR16105, R01 DK47858) and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NSF DMR-0084173). All MR data were acquired at the Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy (AMRIS) facility of the UF McKnight Brain Institute.

Footnotes

In memoriam: During the final writing and editing stages of this manuscript, Dr. Ioannis Constantinidis passed away suddenly in April 2007 at the unjustly young age of 46. Dr. Constantinidis’ dedication to science and the pursuit of knowledge was only surpassed by his dedication to friends and family, of which numerous individuals (including his co-authors) can consider themselves fortunate. ‘Yoda the Greek’ was the driver of a growing research program leading to the development of an artificial pancreas, of which this publication is representative. It was his vision and leadership that made all this possible. This manuscript marks the last on which Ioannis actively worked and drove. In his memory, his co-authors dedicate this article to Ioannis Constantinidis. We are better for having known you, and all the more saddened by your absence.

References

- 1.Kirkpatrick SJ, Hinds MT, Duncan DD. Acousto-optical characterization of the viscoelastic nature of a nuchal elastin tissue scaffold. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:645–656. doi: 10.1089/107632703768247340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason C, Markusen JF, Town MA, Dunnill P, Wang RK. The potential of optical coherence tomography in the engineering of living tissue. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:1097–1115. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/7/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertsching H, Walles T, Hofmann M, Schanz J, Knapp WH. Engineering of a vascularized scaffold for artificial tissue and organ generation. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6610–6617. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guldberg RE, Ballock RT, Boyan BD, Duvall CL, Lin AS, Nagaraja S, Oest M, Phillips J, Porter BD, Robertson G, Taylor WR. Analyzing bone, blood vessels, and biomaterials with microcomputed tomography. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2003;22:77–83. doi: 10.1109/memb.2003.1256276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones AC, Milthorpe B, Averdunk H, Limaye A, Senden TJ, Sakellariou A, Sheppard AP, Sok RM, Knackstedt MA, Brandwood A, Rohner D, Hutmacher DW. Analysis of 3D bone ingrowth into polymer scaffolds via micro-computed tomography imaging. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4947–4954. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantinidis I, Sambanis A. Non-invasive monitoring of tissue engineered constructs by nuclear magnetic resonance methodologies. Tissue Eng. 1998;4:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartman EH, Pikkemaat JA, Vehof JW, Heerschap A, Jansen JA, Spauwen PH. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging explorative study of ectopic bone formation in the rat. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:1029–1036. doi: 10.1089/107632702320934128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neves AA, Medcalf N, Brindle K. Functional assessment of tissue-engineered meniscal cartilage by magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:51–62. doi: 10.1089/107632703762687537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burg KJ, Delnomdedieu M, Beiler RJ, Culberson CR, Greene KG, Halberstadt CR, Holder WDJ, Loebsack AB, Roland WD, Johnson GA. Application of magnetic resonance microscopy to tissue engineering: a polylactide model. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;61:380–390. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stabler CL, Long RC, Jr, Constantinidis I, Sambanis A. In vivo noninvasive monitoring of viable cell number in tissue engineered constructs using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Cell Transplantation. 2005;14:139–149. doi: 10.3727/000000005783983197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stabler CL, Long RC, Jr, Sambanis A, Constantinidis I. Noninvasive measurement of viable cell number in tissue engineered constructs in vitro using 1H NMR spectroscopy. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:404–414. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modo M, Hoehn M, Bulte JW. Cellular MR imaging. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:143–164. doi: 10.1162/15353500200505145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissleder R, Cheng HC, Bogdanova A, Bogdanov AJ. Magnetically labeled cells can be detected by MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imag. 1997;7:258–263. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissleder R, Stark DD, Engelstad BL, Bacon BR, Compton CC, White DL, Jacobs P, Lewis J. Superparamagnetic iron oxide: pharmacokinetics and toxicity. Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:167–173. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodd SJ, Williams M, Suhan JP, Williams DS, Koretsky AP, Ho C. Detection of single mammalian cells by high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Biophys J. 1999;76:103–109. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77182-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster-Gareau P, Heyn C, Alejski A, Rutt BK. Imaging single cells with a 1.5T clinical MRI scanner. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:968–971. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evgenov NV, Medarova Z, Dai G, Bonner-Weir S, Moore A. In vivo imaging of islet transplantation. Nat Med. 2006;12:144–148. doi: 10.1038/nm1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kriz J, Jirak D, Girman P, Berkova Z, Zacharovova K, Honsova E, Lodererova A, Hajek M, Saudek F. Magnetic resonance imaging of pancreatic islets in tolerance and rejection. Transplantation. 2005;80:1596–1603. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000183959.73681.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cahill KS, Gaidosh G, Huard J, Silver X, Byrne BJ, Walter GA. Noninvasive monitoring and tracking of muscle stem cell transplants. Transplantation. 2004;78:1626–1633. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000145528.51525.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta AK, Gupta M. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3995–4021. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terrovitis JV, Bulte JW, Sarvananthan S, Crowe LA, Sarathchandra P, Batten P, Sachlos E, Chester AH, Czernuszka JT, Firmin DN, Taylor PM, Yacoub MH. Magnetic resonance imaging of ferumoxide-labeled mesenchymal stem cells seeded on collagen scaffolds- relevance to tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2765–2775. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito A, Shinkai M, Honda H, Kobayashi T. Medical application of functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;100:1–11. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobson J, Cartmell SH, Keramane A, El Haj AJ. Principles and design of a novel magnetic force mechanical conditioning bioreactor for tissue engineering, stem cell conditioning, and dynamic in vitro screening. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci. 2006;5:173–177. doi: 10.1109/tnb.2006.880823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ino K, Ito A, Honda H. Cell patterning using magnetite nanoparticles and magnetic force. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;97:1309–1317. doi: 10.1002/bit.21322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleischer N, Chen C, Surana M, Leiser M, Rossetti L, Pralong W, Efrat S. Functional analysis of a conditionally transformed pancreatic β-cell line. Diabetes. 1998;47:1419–1425. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.9.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim F, Sun AM. Microencapsulated islets as bioartificial endocrine pancreas. Science. 1980;210:908–910. doi: 10.1126/science.6776628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun AM. Microencapsulation of pancreatic islet cells: a bioartificial endocrine pancreas. Meth Enzymol. 1988;137:575–580. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)37053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papas KK, Long RC, Jr, Constantinidis I, Sambanis A. Role of ATP and Pi on the mechanism of insulin secretion in the mouse insulinoma βTC3 cell line. Biochem J. 1997;326:807–814. doi: 10.1042/bj3260807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stabler C, Wilks K, Sambanis A, Constantinidis I. The effects of alginate composition on encapsulated βTC3 cells. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1301–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambanis A, Papas KK, Flanders PC, Long RC, Jr, Kang H, Constantinidis I. Towards the development of a bioartificial pancreas: Immunoisolation and NMR monitoring of mouse insulinomas. Cytotechnology. 1994;15:351–363. doi: 10.1007/BF00762410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oca-Cossio J, Mao H, Khokhlova N, Kennedy CM, Kennedy JW, Stabler CL, Hao E, Sambanis A, Simpson NE, Constantinidis I. Magnetically labeled insulin-secreting cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webb AG, Grant SC. Signal-to-noise and magnetic susceptibility trade-offs in solenoidal microcoils for NMR. J Magn Reson Part B. 1996;113:83–87. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marquardt DW. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. J Soc Ind App Math. 1963;11:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson NE, Khokhlova N, Oca-Cossio JA, McFarlane SS, Simpson CP, Constantinidis I. Effects of regulating conditionally-transformed alginate-entrapped insulin secreting cell lines in vitro. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4633–4641. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng S-Y, Constantinidis I, Sambanis A. Insulin secretion dynamics of free and alginate-encapsulated insulinoma cells. Cytotechnology. 2006;51:159–170. doi: 10.1007/s10616-006-9025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Constantinidis I, Rask I, Long RC, Jr, Sambanis A. Effects of alginate encapsulation on the metabolic, secretory, and growth characteristics of entrapped βTC3 mouse insulinoma cells. Biomaterials. 1999;20:2019–27. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papas KK, Long RC, Jr, Constantinidis I, Sambanis A. Development of a bioartificial pancreas: I. Long-term propagation and basal and induced secretion from entrapped β TC3 cell cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;66:219–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gross JD, Constantinidis I, Sambanis A. Modeling of encapsulated cell systems. J Theor Biol. 2007;244:500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koenig SH, Brown RD., 3rd Relaxation of solvent protons by paramagnetic ions and its dependence on magnetic field and chemical environment: implications for NMR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1984;1:478–495. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910010407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillis P, Koenig SH. Transverse relaxation of solvent protons induced by magnetized spheres: application to ferritin, erythrocytes, and magnetite. Magn Reson Med. 1987;5:323–345. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910050404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koenig SH, Gillis P. Transverse relaxation (1/T2) of solvent protons induced by magnetized spheres and its relevance to contrast enhancement in MRI. 1988;23:S224–228. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198809001-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delikatny EJ, Poptani H. MR techniques for in vivo molecular and cellular imaging. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;43:205–220. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burtea C, Laurent S, Vander Elst L, Muller RN. Contrast agents: magnetic resonance. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;185:135–165. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72718-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jirak D, Kriz J, Herynek V, Andersson B, Girman P, Burian M, Saudek F, Hajek M. MRI of transplanted pancreatic islets. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1228–1233. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]