Abstract

Little is known about how minority groups react to public information that highlights racial disparities in cancer. This double-blind randomized study compared emotional and behavioral reactions to four versions of the same colon cancer (CRC) information presented in mock news articles to a community sample of African-American adults (n = 300). Participants read one of four articles that varied in their framing and interpretation of race-specific CRC mortality data, emphasizing impact (CRC is an important problem for African-Americans), two dimensions of disparity (Blacks are doing worse than Whites and Blacks are improving, but less than Whites), or progress (Blacks are improving over time). Participants exposed to disparity articles reported more negative emotional reactions to the information and were less likely to want to be screened for CRC than those in other groups (both P < 0.001). In contrast, progress articles elicited more positive emotional reactions and participants were more likely to want to be screened. Moreover, negative emotional reaction seemed to mediate the influence of message type on individuals wanting to be screened for CRC. Overall, these results suggest that the way in which disparity research is reported in the medium can influence public attitudes and intentions, with reports about progress yielding a more positive effect on intention. This seems especially important among those with high levels of medical mistrust who are least likely to use the health care system and are thus the primary target of health promotion advertising.

Introduction

Despite recent landmark progress in reducing overall cancer deaths in the United States (1), African-Americans are still consistently diagnosed with cancer at later stages, have lower 5-year survival rates, and have higher cancer mortality rates than Whites and other groups. Calling attention to such disparities has resonated with public health and scientific leaders, who have made eliminating disparities one of two overarching goals for improving the health of the nation (2) and have allocated significant public funds to better understand/address these gaps. Almost nothing is known, however, about how the public understands and reacts to the same information—cancer data—that highlights racial disparities.

The news media are a major source of health information for the American public (3). The media also determine how scientific findings are framed for public consumption, thus influencing public perception of the issue (4–7). When reporting scientific findings on race and health risk, most news stories are comparative, highlighting differences between racial groups (8). Recent literature reviews of cancer-related news stories in U.S. newspapers reported that nearly one in four cancer-related news stories provided information on racial disparities (9, 10). The overwhelming majority of racially comparative stories emphasize African-Americans’ poorer outcomes rather than Whites’ (or other groups’) favorable outcomes (11). This focus on African-Americans’ relative disadvantage is found in stories about health, finance, criminal justice, education, and employment (12). Although journalistic intent in reporting racially comparative health and cancer information is often noble, to stimulate public concern, pressure policy makers, or motivate individuals to take preventive action (13), it is unclear whether such effects are actually realized, particularly among African-Americans exposed to the information (14).

In general, health promotion advertising often induces high levels of negative emotion or affect to increase self-regulation of health-compromising behaviors (15). However, this negative affect may also induce resistance to the message of the ad. Negative or positive affect can also be associated with an attitude object (e.g., cancer screening; ref. 16). A review of fear and anxiety messages (e.g., fear appeals) suggests that whether one’s emotional reaction leads to behavior change is dependent on other personal and situational variables (e.g., feeling competent and motivated to engage in the behavior; ref. 16).

Many models of attitude change and persuasion include affect or emotion as a mediating or intermediate process between message exposure and attitude change and/or behavioral outcomes. For example, the Elaboration Likelihood Model suggests that the type of cognitions or thoughts that a recipient has in response to a message and the affect attached to each of those thoughts (positive, negative) predict attitude change and subsequent behavioral outcomes (17). A review of advertising theory found that many theories and models suggested that affect, either alone or with other variables, influenced attitude change (18). Petty and Wegener (16) suggested a generic, general processes model with affective, cognitive, and behavioral processes mediating the effects of the independent variables of source, message, recipient, and context variables on the outcome variable of attitude change.

From the perspective of behavior change theories, one might expect that exposure to cancer risk information about one’s racial group would increase the likelihood of taking preventive action. The Precaution Adoption Process Model, for example, proposes that the transition from being unengaged in a problem to deciding whether to take action to prevent the problem is influenced by a person’s belief that the problem is likely to occur in his or her community or among similar others (19, 20). According to the Health Belief Model, exposure to cancer risk information about one’s racial group should increase perceived personal susceptibility to cancer, which can, under certain circumstances (e.g., more perceived benefits than perceived barriers to making risk-reducing changes), increase the likelihood of wanting to or intending to engage in behavior change (21).

On the other hand, exposure to racially comparative information might have the opposite effect. Repeatedly hearing that one’s group is worse off could lead to active avoidance, devaluation, or rejection of the information. For example, people tend not to believe, or view as prejudiced, information that threatens their self-concept or favorable image of their referent group (22, 23). In addition, no behavioral change theories posit that a consistent emphasis on a group’s comparative failure is an effective way to increase its members’ motivation to change.

This may be especially relevant for health disparity information given that African-Americans report greater mistrust of and higher rates of perceived discrimination when engaging the health care system (24–28). Although these attitudes are insufficient to cause a refusal of lifesaving treatments (29), they have been associated with delays in seeking health care and discussed as factors related to health information seeking (26, 30). Consequently, it is worthwhile to evaluate whether individuals’ level of medical mistrust influences their response to health disparity information and their wanting to be screened after being exposed to cancer information that includes a suggestion to be screened.

To determine whether racially comparative cancer information might have unintended negative consequences, this randomized study compared reactions to four versions of the same colon cancer (CRC) information presented in mock news articles to a community-based sample of African-American adult men and women. The articles emphasized either the impact of CRC on African-Americans, the progress African-Americans have made over time in reducing their CRC risk, or one of two types of disparity in CRC mortality between African-Americans and Whites. Understanding the effects of race-specific cancer information can help future public communication efforts designed to eliminate cancer disparities.

The specific hypotheses that were evaluated in this study were the following. (a) Positive and negative affect. There will be a main effect of message type on emotions such that Disparity messages will elicit more negative affective response and less positive affective response than Progress messages. Impact messages will fall between the other two conditions in eliciting positive and negative affective response. (b) Behavioral desire (wanting) to be screened for CRC. There will be a main effect of message type on behavioral intent such that the Progress message will result in individuals wanting to be screened more than the Disparity message. The Impact message will fall between the other two conditions in influencing wanting to be screened. There will also be a main effect of medical mistrust such that those higher in medical mistrust will be less likely to want to be screened than those with lower medical mistrust. Given the negative and possibly threatening nature of the Disparity message, it is possible that low mistrust participants in the Disparity condition will be least likely to want to be screened. In addition, a mediational analyses will be conducted to evaluate whether negative or positive affect mediated the influence of message type on individuals wanting to be screened.

Materials and Methods

The University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Participants and Protocol

African-American men and women (n = 300) were recruited through locally sponsored health fairs, advertisements on a local radio station that is popular among the older local African-American community (whose playlist is described as combining “oldies” and “gospel”), and in the local Black newspaper. In addition, recruitment flyers were given to local community contacts to distribute at their respective organizations. The advertisement informed individuals that they would be involved in helping create health news articles designed specifically for African-Americans.

Eligible participants were ages 40 and older with no history of CRC and able to read and respond to printed information. Persons ages 40 to 49 years were included because current guidelines recommend CRC screening when the risk for CRC is high (e.g., due to family history; refs. 31–33), because racial disparities in CRC justify earlier education efforts for African-Americans, and because CRC screening was not an outcome in the study. Compared with the overall population of African-American adults in the St. Louis region, this sample included proportionately more high school graduates and women. But these characteristics were distributed equally across study groups by randomization.

In a randomized double-blind experiment (group assignment was unknown to participants and research staff), participants were informed about the study, completed a baseline survey, read one of four randomly assigned mock newspaper articles, and completed an immediate postexposure survey. All research activities were completed in a controlled laboratory setting and participants received a $20 grocery store gift card on completion.

Mock News Articles

The mock news articles were professionally prepared and modeled in form, style, typology, and graphics after USA Today. All four were identical in size and appearance and shared the same structural elements: headline, subheadline, sidebar, graphic, and pull quote. Seven areas of content were also identical: byline, dateline, source (National Cancer Institute), a quote from former U.S. Surgeon General Dr. David Satcher, a list of risk factors associated with lower rates of CRC screening, descriptions of three CRC screening tests, and referral to three web and telephone sources of information on CRC and screening. Data on CRC mortality rates (from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; ref. 34), interpretation of risk factors, and a quote from the same (fictitious) community member were also included in all articles but varied by study condition. Both the articles and the recruitment materials were developed by a team experienced in creating health communication materials for African-American audiences, including a content developer, graphic artist, and behavioral and social scientists.

The four variants of the article are distinguished by their framing and interpretation of the CRC mortality data. In short, they were (a) impact (CRC is an important problem for Black Americans); (b) disparity, current (Blacks are doing worse than Whites); (c) disparity, over time (Blacks are improving, but less than Whites); and (d) progress (Blacks are improving over time). Because participant responses to the two disparity articles were indistinguishable, they were combined into a single “disparity” group for all analyses. All articles were in the 11th grade reading level range. Table 1 shows exact differences in content across the four articles.

Table 1.

Differences in framing and interpretation of race-specific CRC information by study group

| Content of mock article | Study group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact | Disparity (current) | Disparity (over time) | Progress | |

| Headline | Colon cancer striking Blacks at high rate | Blacks die from colon cancer at higher rate than Whites | Black-White gap in colon cancer deaths growing | Blacks making great strides against colon cancer |

| Subheadline | Thousands of Black men and women die each year | Death rate higher for Black men and women | Gap is greater now than 20 years ago | Death rates decreasing in the Black community |

| Mortality data | … colon cancer claims the lives of more Black men and women in the U.S. than all cancers except lung and breast. It is expected that 7,000 Black men and women will die from colon cancer this year alone. | …death rates from colon cancer among Blacks are almost 50% higher than among Whites. Much of this disparity is due to Blacks being less likely to get tested for colon cancer. | …death rates from colon cancer among Blacks are nearly 50% higher than among Whites. The size of the gap is greater than it was 20 years ago. | …colon cancer death rates for Blacks have dropped 14% in the past 20 years. Much of this improvement is due to a growing number of Blacks who are protecting their health by being tested for colon cancer. |

| Comment on risk factors | Overcoming these obstacles may be especially important in the Black community. | All these factors affect Blacks more than Whites. | All these factors affect Blacks more than Whites. | Despite these obstacles, almost 5.3 million Blacks are screened for colon cancer every year. |

| Quote from community member | “Our community faces problems every day and clearly this is a major problem. We need to work together to find ways to get more of us screened for colon cancer.” | “With all the problems we have to deal with, it’s not surprising that Blacks are more likely to die from cancer than Whites. It’s just one more problem our community faces.” | “It’s hard to believe we’re worse off than” we were 20 years ago. Maybe I shouldn’t be surprised. With all the problems Blacks face, it makes sense we’d have higher rates of this disease, too.” | “This is great news for us. Despite the problems we face every day, the Black community is doing what it takes to improve our health.” |

Preexposure Measures

Participants were asked if they had previously been screened for CRC (yes/no), the extent to which they were planning on being screened in the next 6 months (1 = not considering it at this time; 5 = have been screened and will continue), and the extent to which they agreed that CRC was an important health problem (five-point scale, strongly agree-strongly disagree). To help mask the purpose of the study, similar questions were asked about seven other health- and cancer-related behaviors and screenings. The 12-item Medical Mistrust Scale (MMS; ref. 35) was also administered. The MMS has been validated as a measure of mistrust in the medical community and was found to have adequate internal consistency in the current study (α = 0.82). For analyses, participants were classified as having high or low medical mistrust using a median split.

Postexposure Measures

The primary study outcomes were emotional responses to the article and wanting to be screened for CRC. After reading the article, participants indicated on a five-point scale (strongly disagree-strongly agree) the extent to which they felt each of seven positive and three negative emotions from the Positive and Negative Affectivity Scale (36). When considering what items of the Positive and Negative Affectivity Scale to use, a group of five experts in research communication selected those items that were judged most likely to be effected by race-specific communication. Responses to positive items were averaged to create a “Positive Emotion” mean and responses to negative items were averaged to create a “Negative Emotion” mean. Reliability was α = 0.89 for negative emotions and α = 0.70 for positive emotions. Participants also indicated how strongly they agreed or disagreed (five-point scale, strongly disagree-strongly agree) with the intention statement, “I want to be screened for colon cancer so I will know if I have it.” The word “want” was chosen as a more common place term for “intention” based on internal research with members of the local community. In addition, five yes/no questions about article content were asked to determine whether the groups differed with regard to understanding the article. Age, gender, education level, and income were also reported.

Data Analyses

Between-group analysis of covariance controlling for history of CRC screening, perceived importance of CRC, age, and gender evaluated differences in positive and negative emotional response and behavioral intention to be screened by MMS. Mediational analyses were conducted examining whether negative or positive affective response to the articles mediated the influence of message type on the extent to which individuals wanted to be screened for CRC among those who received either a positive or negative message only. The test for mediation was conducted using the Sobel test (37–40). Where significant differences were found, the 95% confidence interval of difference (CID) was calculated. Six participants were excluded from analyses due to age <40 (n = 3) and missing data postexposure (n = 3). Analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 14.0.1 for Windows (41).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Most participants (mean age, 54.4) were women (76%), had completed high school (89%), and reported an annual household income of $25,000 or more (57%). Less than half of participants (45%) had been screened for CRC, although most viewed it as an important problem (mean, 4.27 on 1–5 scale). Medical mistrust scores were moderate (mean, 31.1; scale range, 12–60). None of these variables differed by study group at baseline.

Comprehension of the Article

Results indicated that no significant differences existed among groups with regard to article comprehension.

Affective Response

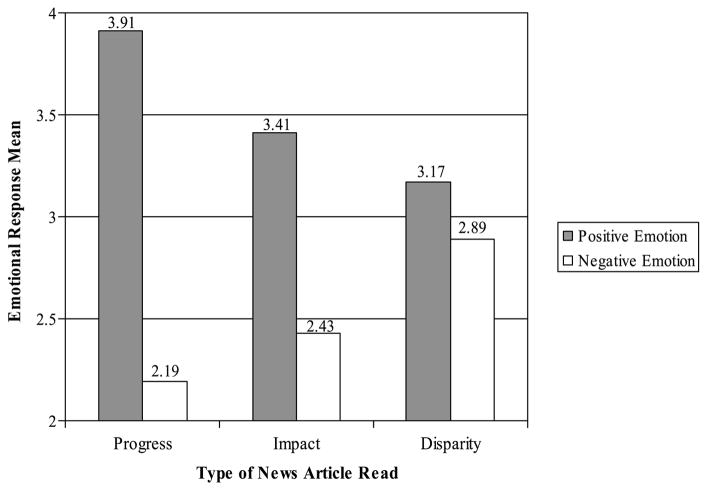

Figure 1 shows mean positive and negative emotional responses to each article. Positive emotional response was significantly different across groups (F = 13.00, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.10), with the “Progress” article (M = 3.91, SD = 0.90) eliciting more positive emotional response than either the “Impact” (M= 3.41, SD = 1.12, CID = 0.21–0.98) or “Disparity” (M = 3.17, SD = 1.10, CID = 0.51–1.15) articles. There was no difference in positive emotional responses to the Impact and Disparity articles.

Figure 1.

Positive and negative affective response to reading news article by type of news article read.

Negative emotional response was also significantly different across groups (F = 10.31, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.08), with the Disparity article (M = 2.89, SD = 1.10) eliciting more negative emotional response than either the Impact (M= 2.43, SD = 1.05, CID = 0.14–0.79) or Progress (M = 2.19, SD = 0.99, CID = 0.38–1.03) article. There was no difference in negative emotional responses to the Impact and Progress articles.

Behavioral Desire (Wanting) to be Screened

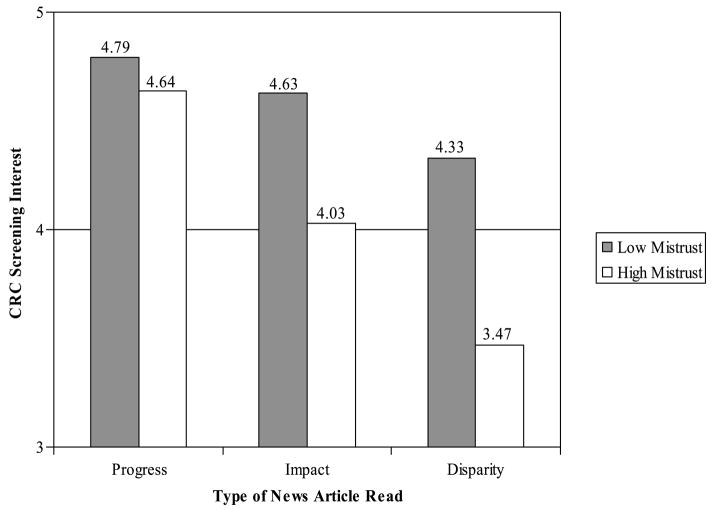

Figure 2 shows group means for wanting to be screened by level of medical mistrust. The main effect for study group was significant (F = 13.77, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.09), with those reading the Progress article significantly more likely to want to be screened for CRC (M = 4.72, SD = 0.58) than those reading either the Impact (M = 4.33, SD = 0.84, CID = 0.02–0.75) or Disparity (M = 3.90, SD = 1.36, CID = 0.50–1.13) articles. In addition, those reading the Impact article were more likely to want to be screened than those reading the Disparity article (CID = 0.11–0.74). The main effect for MMS was also significant (F = 14.81, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.05). Those with lower MMS scores were significantly more likely to want to be screened (M = 4.58, SD = 0.86) than those with high MMS scores (M = 4.05, SD = 1.33, CID = 0.26–0.81).

Figure 2.

Behavioral desire (wanting) to be screened, by medical mistrust.

The study group by MMS interaction was marginally significant (P = 0.07). However, when comparing only the Progress and Disparity groups, a significant interaction is found (F = 4.53, P < 0.05, η2 = 0.02). Analysis of the simple effects indicated that those with higher MMS scores who read the Progress article were more likely to want to be screened for CRC (M = 4.64, SD = 0.65) than those with high MMS who read the Disparity article (M = 3.47, SD = 1.55, CID = 0.73–1.61).

Mediational Analysis

To evaluate whether affective responses to the articles mediated the relationship between what was emphasized in the messages and the extent to which individuals wanted to be screened for CRC, mediational analysis was conducted. Initially, bivariate correlations were conducted to determine the relationship of message type, negative affective response, positive affective response, and wanting to be screened for CRC (Table 2). Results indicated that all correlations were significant (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Correlations between type of news article read, affective response to the article, and wanting to be screened for CRC

| Message type | Negative affect | Positive affect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Message type | — | ||

| Negative affect | −0.30 | — | |

| Positive affect | 0.37 | −0.41 | — |

| Want to be screened | 0.28 | −0.31 | 0.21 |

NOTE: All correlations significant P < 0.001.

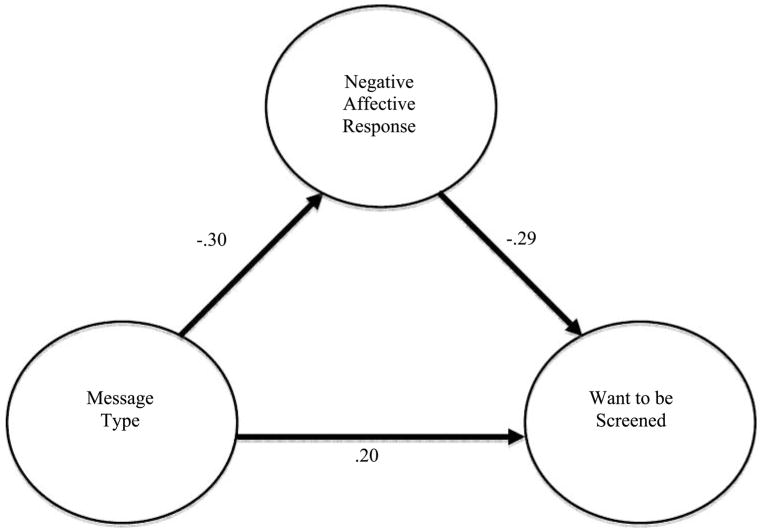

Once it was established that a relationship existed among the variables, steps were taken to evaluate whether negative affective response and positive affective response mediated the relationship between message type and wanting to be screened for CRC. As can be seen in Fig. 3, the results indicated that negative affective response did mediate the relationship between message type and wanting to be screened (Sobel test for mediation = 3.48, P < 0.001). The finding indicated that message type (dummy coded so 1 = positive message) was correlated with lower negative affective response (r = −0.30, P < 0.001). In addition, the greater the amount of negative affective response, the less likely an individual was to want to be screened after controlling for message type (r = −0.29, P < 0.001). When controlling for the effect of negative affective response, the relationship between message type and wanting to be screened was diminished (r = 0.20 versus 0.28 without controlling for negative affect). This indicates that the higher the negative affect, the less likely an individual wanted to be screened for CRC.

Figure 3.

Negative affective response mediates the relationship between type of news article read and wanting to be screened for CRC.

Mediational analysis was also conducted to see whether positive affect mediated the relationship between message type and wanting to be screened. However, the test for mediation was not significant (Sobel = 1.74, P = 0.08).

Discussion

Cancer information that emphasizes racial disparities may undermine prevention and control efforts among African-Americans, especially those with a high level of medical mistrust. Findings showed that information emphasizing the progress African-Americans are making in increasing CRC screening and decreasing CRC mortality led to significantly more positive reactions to cancer news stories, being more likely to want to participate in cancer screening, and counteracted the negative effects of medical mistrust. At the same time, negative affective response to the articles had a deleterious impact on the likelihood of wanting to be screened and mediated the relationship between message type and wanting to be screened for CRC. These data suggest that emphasizing progress in disparities research may have a more positive influence on affect and intentions to screen than emphasizing racial disparities. This positive influence seems especially important among those with high levels of medical mistrust who are least likely to use the health care system and are thus the primary target of health promotion advertising.

Much is left to learn about the effects of using race-specific information in cancer communication. First, this study did not examine how such information is processed or identify mechanisms through which it might lead to the effects observed. Candidate explanations might include a range of self-protective strategies identified in social psychological research as helping members of stigmatized groups cope with negative information and attributions about themselves and their identity group (22). It is also possible, as observed elsewhere, that making available or priming a racial stereotype (as disparity information might do) may be sufficient to suppress African-Americans’ performance on related tasks (42).

The apparent beneficial effects of information focusing on African-Americans’ progress in reducing cancer death rates should also be further explored. For example, exposure to such information might alter one’s perceptions of group social norms (e.g., perceiving that getting screened for CRC is something most African-Americans do), thereby increasing one’s interest in screening. Alternatively, positive reactions to the progress approach may simply reflect the novelty in the information environment. Finally, do these messages affect behavior, and not just intention?

The manner whereby the media choose to frame the discussion of differences in racial health behavior and risk can have varied behavioral and sociopolitical implications (5, 6). It is possible that mainstream media emphasis on disparities has deleterious effects on health behavior among parts of the African-American population. At the same time, such stories may provide support for those supporting legislative action to fund programs aimed at further reducing disparities. It is possible that a shift in the mainstream media to messages emphasizing progress could provide motivation for individuals to engage in healthy behaviors. At the same time, opponents of programs designed to reduce health disparities might use progress-framed messages as an argument against the need for any further funding of such programs.

There were limitations to the current study that need to be acknowledged. The sample population included proportionally more high school graduates and women. This may have been a result of the advertisement that invited individuals to help create health news articles for African-Americans. However, these characteristics were distributed evenly across study groups by randomization. In some ways, the findings are even more striking because medical mistrust is higher in lower educated populations (30). Another potential limitation of the study was that the articles were at an 11th grade reading level. However, this was done to mimic actual newspaper articles (as opposed to creating low literate articles). Moreover, analyses of comprehension revealed that there were no differences in groups and the large majority of responses concerning comprehension were correct. This might be due to the fact that the group had higher levels of high school graduates or because certain medical terminology increased the reading level of the articles. Another potential limitation of the study was that the constructs of “risk perception” and “intention to be screened” were not directly measured in the current study. Although risk perception is an important issue, it was decided to not directly assess this issue in the current study to minimize participant burden. In addition, rather than asking whether an individual intended to be screened, the current study evaluated whether the individuals wanted to be screened for CRC. Although these two constructs are conceptually similar, they can be potentially different. It is possible that some individuals would have answered differently if the questions had been about intention to be screened rather than wanting to be screened. At the same time, it is likely that most individuals who intend to be screened also want to be screened. Despite this potential limitation, the current findings about how wanting to be screened is influenced by how the message is delivered is an intriguing finding. Finally, although a mediational analysis was conducted, it is important to keep in mind that cross-sectional data are unable to provide information on causality or temporality.

From a practical standpoint, these findings suggest that cancer communication messages that include race-specific data for African-Americans will be better received and have greater impact when they emphasize the progress African-Americans are making. However, progress-framed messages must be supported by actual cancer incidence, mortality, or screening data, and in some cases real “progress” may be harder to find. In such instances, findings from this study suggest that impact framing—simply describing the impact of cancer on a population—is also preferable to using racially comparative disparity data. At the same time, little published research has evaluated how to best implement communication campaigns that use progress framing to improve healthy behaviors. Research of this type will provide cancer researchers and communicators with the tools they need to report new science in ways that are accurate but that also influence health behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Cancer Institute Centers of Excellence in Cancer Communication Research program (CA-P50-95815). R.A. Nicholson was supported by the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke grant K23-NS-048288.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Washington (DC): U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viswanath K. Science and society: the communications revolution and cancer control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:828–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-setting. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholson C. APS Observer. 2007. Framing science: advances in theory and technology are fueling a new era in the science of persuasion; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nisbet MC, Mooney C. Science and society. Framing Science Science. 2007;316:56. doi: 10.1126/science.1142030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: the role of message framing. Psychol Bull. 1997;121:3–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer E, Endreny P. Reporting on risk: how the mass media portray accidents, diseases, disasters and other hazards. New York: Russell Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caburnay CA, Kreuter MW, Cameron G, et al. Black newspapers as a tool for cancer education in African American communities. Manuscript under review. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen E, Caburnay C, Luke D, Rogers S, Cameron G. Cancer coverage in general population and black newspapers. J Health Commun. doi: 10.1080/10410230802342176. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandy OH. If it weren’t for bad luck: framing stories of racially comparative risk. In: Berry V, Manning-Miller C, editors. Mediated messages and African American culture: contemporary issues. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1996. pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandy OH. Framing comparative risk: a preliminary analysis. Howard Journal of Communication. 2005;16:71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambeth E, Meyer P, Thorson E, editors. Assessing public journalism. Columbia (MO): University of Missouri Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gandy OH. Racial identity, media use, and the social construction of risk among African Americans. Journal of Black Studies. 2001;31:600–18. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown SL. Emotive health advertising and message resistance. Australian Psychol. 2001;36:193–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petty RE, Wegener DT. Attitude change: multiple roles for persuasion variables. In: Gilbert D, Fiske S, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 1. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 323–90. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT, Strathman AJ, Priester JR. To think or not to think: exploring two routes to persuasion. In: Brock TC, Green MC, editors. Persuasion: psychological insights and perspectives. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2005. pp. 81–116. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vakratsas D, Ambler T. How advertising works: what do we really know? J Marketing. 1999;63:26–43. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinstein ND, Sandman P. A model of the precaution adoption process: evidence from home radon testing. Health Psychol. 1992;11:170–80. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinstein ND, Lyon JE, Sandman PM, Cuite CL. Experimental evidence to stages of precaution adoption. Health Psychol. 1998;17:445–53. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker M. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:324–473. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crocker J, Voelkl K, Testa M, Major B. Social stigma: the affective consequences of attributional ambiguity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:218–28. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunning D, Leuenberger A, Sherman DA. A new look at motivated inference. Are self-serving theories of success a product of motivated forces? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaVeist TA, Nickerson K, Bowie J. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and White cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:146–61. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lillie-Blanton M, Brodie M, Rowland D, Altman D, McIntosh M. Race, ethnicity, and the health care system: public perceptions and experiences. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:218–35. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthews A, Sellergren S, Manfredi C, Williams M. Factors influencing medical information seeking among African American cancer patients. J Health Commun. 2002;7:205–19. doi: 10.1080/10810730290088094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1747–59. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams DR, Rucker TD. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21:75–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geiger HJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in diagnosis and treatment: a review of the evidence and a consideration of causes. In: Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2003. pp. 417–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, Berg AO, Lohr KN. Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Annals Intern Med. 2002;137:132–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research Quality; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services. Publication No. 05–0570. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. Sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Clegg L, Mariotto A, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK, editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2002 [monograph on the Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2005. [cited 2007 May 14] Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson H, Valdimarsodottir H, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W. The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004;38:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers and Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Rev. 1993;17:144–58. [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivar Behav Res. 1995;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) [computer program]. Version 14.0.1. Chicago: SPSS, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steele C, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]