Abstract

Dual oxidases (Duox1 and Duox2) are plasma membrane-targeted hydrogen peroxide generators that support extracellular hemoperoxidases. Duox activator 2 (Duoxa2), initially described as an endoplasmic reticulum resident protein, functions as a maturation factor needed to deliver active Duox2 to the cell surface. However, less is known about the Duox1/Duoxa1 homologues. We identified four alternatively spliced Duoxa1 variants and explored their roles in Duox subcellular targeting and reconstitution. Duox1 and Duox2 are functionally rescued by Duoxa2 or the Duoxa1 variants that contain the third coding exon. All active maturation factors are cotransported to the cell surface when coexpressed with either Duox1 or Duox2, consistent with detection of endogenous Duoxa1 on apical plasma membranes of the airway epithelium. In contrast, the Duoxa proteins are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum when expressed without Duox. Duox1/Duoxa1α and Duox2/Duoxa2 pairs produce the highest levels of hydrogen peroxide, as they undergo Golgi-based carbohydrate modifications and form stable cell surface complexes. Cross-functioning pairs that do not form stable complexes produce less hydrogen peroxide and leak superoxide. These findings suggest Duox activators not only promote Duox maturation, but they function as part of the hydrogen peroxide-generating enzyme.—Morand, S., Ueyama, T., Tsujibe, S., Saito, N., Korzeniowska, A., Leto, T. L. Duox maturation factors form cell surface complexes with Duox affecting the specificity of reactive oxygen species generation.

Keywords: Dual oxidase, NADPH oxidase, Nox, NIP

Dual oxidases (Duox1 and Duox2) are Nox family NADPH:O2 oxidoreductases that appear to function as dedicated plasma membrane hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) generators that support several extracellular hemoperoxidases (1). Duox enzymes were initially identified as H2O2 sources involved in thyroperoxidase-mediated organification of iodide during thyroid hormone biosynthesis (2, 3). Lesions in the DUOX2 gene were identified in patients with congenital hypothyroidism (4,5,6). Duox enzymes are also detected in exocrine (salivary) glands and on mucosal surfaces (airways, gastrointestinal tract), where they were proposed to support the antimicrobial activity of lactoperoxidase (7). Furthermore, sea urchin Duox (Udx1) provides extracellular H2O2 used in ovoperoxidase-mediated oxidative cross-linking of the fertilization envelope (8). The issues of whether Duox1 and Duox2 function as single-component oxidases capable of generation and utilization of H2O2 are controversial (1, 9,10,11). Several surface-exposed Nox family enzymes produce superoxide (O2·−) directly by transfer of a single electron to molecular oxygen (12), however Duox isozymes function as efficient H2O2 generators on the cell surface (13,14,15). In both endocrine and exocrine tissues, Duox accumulates on the apical plasma membrane of polarized cells (13, 16,17,18), consistent with a functional partnership with extracellular peroxidases.

Attempts to reconstitute heterologously expressed Duox enzymes have been unsuccessful (19) until Duox activator 2 (Duoxa2) was identified as a maturation factor that enables Duox2 to exit the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and rescues oxidase activity on cell surfaces (20). Intracellular trafficking of Duox2 and Duoxa2, constructed as tagged fusion proteins, suggested Duoxa2 is retained as an ER-resident protein but is needed to allow the ER-to-Golgi transition of Duox2. Mutations in Duoxa2 were later identified in congenital hypothyroid patients that block the ER-to-Golgi transition of Duox (21). The DUOX2/DUOXA2 genes, and their paralogs (DUOX1/DUOXA1), are aligned head-to-head in a compressed genomic locus on chromosome 15, suggesting expression of each oxidase and its maturation factor is coordinated by a common bidirectional promoter (20). Recently, Duoxa1 was shown to restore Duox1 activity (22).

Here, we explored targeting and reconstitution of Duox1 or Duox2 coexpressed with various Duox maturation factors. While cloning hDUOXA1 cDNA, we identified four alternative splicing variants, two of which support maturation of either Duox1 or Duox2. Furthermore, we show that the active maturation factors not only enable Duox exit from the ER but are targeted to the cell surface in complexes with Duox and affect the type of reactive oxygen species released by the enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Flp-In 293 cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and COS-7 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in minimum essential medium-α and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimum essential medium, respectively, both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Transfections were performed using FuGENE6 following manufacturer’s guidelines (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Stable isogenic Flp-In 293 clones were selected with 100 μg/ml hygromycin (Invitrogen) and checked for the absence of β-gal staining (Invitrogen). Each clone was routinely assayed by Western blot analysis to monitor possible changes in Duox or Duoxa protein expression or contamination by other clones.

Single-passage normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) were cultured in bronchial/epithelial basal medium that included all SingleQuot bronchial epithelial cell growth medium supplements (Lonza). Before cell lysis for protein extraction, confluent NHBE cells were stimulated (or not) for 72 h with 10 ng/ml interleukin-13 (RD Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

cDNA cloning and construction of expression vectors

DUOX1, DUOX2, DUOXA1, and DUOXA2 open reading frames (ORFs) were amplified by PCR using PfuUltra HF DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) from human thyroid gland cDNA (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA), cloned into pcDNA3.1D/V5-His-TOPO, and subcloned into pcDNA5/FRT (Invitrogen). A common DUOXA1 forward primer (5′-CACCATGGCTACTTTGGGACACACATTCCCC-3′) and two distinct reverse primers (5′-TTATAAAGCACAATCAGGATCTTTGGGG-3′ and 5′-CTAGATTAGAGGTGTGTGGCGGGAGG-3′) were designed to amplify short and long DUOXA1 isoforms, respectively. Each PCR tube contained 2.5 μM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dNTP, 0.5 μM of each primer, 5 U of polymerase and 4 ng of tissue cDNA template. Amplification reactions were performed over 41 cycles using the following program: 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min. Epitope-tagged constructs were prepared using the Quickchange II site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). To generate bicistronic DUOXA/DUOX expression vectors, DUOXA ORFs were initially cloned into the MCS-A of pIRES vector (Clontech), and DUOXA-IRES cassettes were subsequently subcloned into pcDNA5/FRT upstream of DUOX ORF. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Structural predictions were performed with Signal3.0P (23) and Phobius algorithms (24). Supplemental Table 1 lists all expression vector constructs and transfection systems used in this study.

Cell lysis, N-deglycosylation, and immunoblot analysis

Cell extracts were prepared in RIPA buffer (Boston Bioproducts, Worcester, MA, USA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) by rocking for 30 min at 4°C and cleared by centrifugation (16,000 g, 10 min, 4°C). Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA method (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of proteins (10–20 μg) were treated or not with 1000 U of N-glycosidase F or endoglycosidase H (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) for 1 h at 37°C, separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were blocked in Blotto/Tween/TBS buffer (Boston Bioproducts) overnight at 4°C and probed for 2 h at room temperature (RT) with anti-V5-HRP (1:5000; Invitrogen), anti-actin-HRP (1:10,000; Sigma), anti-HA (1:1000; Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA), or anti-Duox (1:2500; kindly provided by Dr. Corinne Dupuy, Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France) (17). Anti-Duoxa1 serum was raised in rabbits immunized with a CETINYNEEFTWRLGENYA-amide peptide conjugated through its amino terminus to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. The peptide differs from Duoxa2 at three residues (ETINDNEQFTWRLKENYA). When necessary, blots were subsequently incubated with HRP-conjugated goat antibodies for 30 min at RT (1:2000; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Immune complexes were detected by chemiluminescence using an ECL Plus kit (GE Healthcare).

Indirect immunofluorescence (IF)

Cells grown on collagen-coated glass-bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA, USA) were fixed 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS, permeabilized (or not) with 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS, and blocked with PBS/5% bovine serum albumin/5% normal goat serum. Cells were then incubated 2 h at RT with anti-HA (1:100; Covance), anti-V5 (1:200; Invitrogen), anti-Duoxa1 serum (1:100), or H-70 anti-calnexin (1:50; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), and staining was revealed with Alexa Fluor-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1000; Invitrogen). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Invitrogen).

Paraffin sections of normal human tracheal tissue from anonymous healthy donors were obtained from the Laboratory of Pathology (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA), following approval by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Program Office of Human Subjects Research. Deparaffinized sections were deglycosylated [2 h, 37°C with 5000 U N-glycosidase F in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5], followed by an epitope retrieval step (1 h, 85°C incubation in 10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0). After blocking with PBS/5% bovine serum albumin/5% normal goat serum, sections were incubated 2 h at RT with anti-Ezrin, an apical plasma membrane marker (1:100, clone 3C12; Invitrogen) and anti-Duoxa1 serum (1:100). Bound antibodies were revealed with Alexa Fluor-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1000; Invitrogen), and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Invitrogen). Slides were mounted with ProLong antifade reagent (Invitrogen). Images were collected on a Leica SP2 confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscope using an ×63 oil-immersion objective, NA 1.4 (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

NADPH oxidase assays

Three distinct methods were used in parallel to detect NADPH oxidase activity. Trypsinized cells were washed twice, resuspended in 1× Earle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS) (E3024; Sigma) containing 25 mM HEPES (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) and counted in trypan blue solution (Lonza). Trypsinization did not alter whole cell Duox activity when compared with cells harvested with EDTA solution, as shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. Extracellular H2O2 production was measured on cells resuspended in EBSS-HEPES buffer using homovanillic acid (1 mM; Sigma) which on H2O2-dependent oxidation in the presence of exogenous peroxidase (10 U/ml horseradish peroxidase I; Sigma) generates a highly fluorescent dimer (2,2′-dihydroxy-3,3′-dimethoxydiphenyl-5,5′-diacetic acid) (25). Fluorescent kinetics measurements monitoring formation of oxidized homovanillic acid following cell stimulation by 1 μM ionomycin (or not) were performed in 96-well black plates (5×105 viable cells/200 μl well) at 37°C in a Fluoroskan fluorometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA) using excitation and emission filters set at 320 and 405 nm, respectively. Extracellular O2·− release was detected by chemiluminescence using superoxide dismutase (SOD)-inhibitable Diogenes reagent (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA, USA) on cells resuspended in EBSS-HEPES buffer (26). Kinetics measurements were performed in 96-well white plates (5×105 viable cells/200 μl well) at 37°C in a Luminoskan luminometer (Thermo). Extracellular O2·− production was also quantified based on assays of SOD-inhibited cytochrome c reduction using a molar extinction coefficient of 21 mM−1.cm−1 at 550 nm (27). Viable cells (5×105) were suspended in 200 μl EBSS-HEPES containing 100 μM cytochrome c (Sigma), incubated 10 min at 37°C following stimulation (or not) by 1 μM ionomycin, centrifuged 30 s at 10,000 g, and then the absorbance of the supernatant fraction was determined. NADPH oxidase activity was inhibited by 10 min prior incubation with the flavo-enzyme inhibitor diphenylene iodonium (DPI, 10 μM; Sigma) (28).

Immunoprecipitation of cell surface Duox complexes

Attached cells, preblocked in PBS/0.02% azide/2% fetal bovine serum (10 min, 4°C), were incubated with 10 μg/ml of anti-HA antibody (30 min, 4°C) to bind surface-exposed HADuox. Washed cells were lysed with cold 1% Nonidet P-40 buffer (Boston Bioproducts) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) by rocking for 15 min at 4°C. Cleared supernatants were incubated 1 h (4°C) with 50 μl protein-G Sepharose (GE Healthcare) to capture immune complexes. After three washes in lysis buffer, bound proteins were eluted in 4× LDS buffer (Invitrogen) and subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell-surface-exposed epitopes

Surface-expressed peptide epitopes were detected on trypsinized cells (106) that were sequentially incubated (30 min each) with anti-HA (1:100; Covance) and Alexa488-conjugated anti-mouse (1:100; Invitrogen) in PBS/2% FBS at 4°C. Fluorescence was monitored using a FACSort flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) after washing in PBS containing 3 μM propidium iodide to detect damaged cells. Twenty thousand events were acquired for each experiment.

GenBank accession numbers

DUOXA1 mRNA splice variant nucleotide sequences were deposited under accession numbers EU927394 (α), EU927395 (β), EU927396 (γ), and EU927397 (δ).

RESULTS

Identification of DUOXA1 mRNA splice variants

A comparison of available sequences suggested alternative mRNA splicing among DUOXA1 transcripts (e.g., GenBank accession numbers BC020841, BC029819, DQ489735). To confirm this observation, we designed two PCR primer sets, including a common forward primer encompassing the start codon and two different reverse primers targeting two different stop codons (Fig. 1A). These primer pairs generated the same four distinct amplicons following 41 PCR cycles when using human cDNA templates from lung, small intestine, and thyroid gland; tissues where DUOXA1 ESTs have been identified (Fig. 1B). Sequencing revealed four DUOXA1 ORFs (α, β, γ, and δ) arising from two alternative splicing events: at the first splice site ORFα and ORFγ retain the third coding exon, whereas ORFβ and ORFδ lack these 135 nt but maintain the same reading frame. Alternative splicing at the second site occurs within the sixth coding exon, providing two additional coding exons within ORFγ and ORFδ that are flanked by consensus (GT-AG) splicing donor and acceptor sequences (29).

Figure 1.

Alternate mRNA splice variants of DUOXA1. A) Schematic of alternatively spliced DUOXA1 ORFs, showing exon sizes. Arrowheads represent alternative splicing sites; black boxes show distinct C-terminal coding sequences; arrows denote positions of PCR primers. B) PCR amplification (41 cycles) of short (α,β) and long (γ, δ) transcripts from human tissue cDNA sources. β and δ transcripts lack the third coding exon. C) Predicted proteins encode 5 transmembrane sequences. Black circles delineate varying C-terminal sequences; gray denote exon 3-encoded sequence (45 aa) including two N-glycosylation sites (Y) absent from β and δ forms. Dotted circles represent peptide (Duoxa1α aa 122–139) used to raise the anti-Duoxa1 serum.

Sequence analysis of all four DUOXA1 ORFs predict membrane proteins comprising five transmembrane segments, including a reverse signal anchor with an external N terminus (Fig. 1C), similar to Duoxa2. Duoxa1α, previously identified (DQ489735), is the closest homologue of Duoxa2 having similar length (343 vs. 320 aa), 58% identical residues, and all three NX(S/T) consensus sites for N-glycosylation within the first extracellular loop. Duoxa1γ represents the human homologue of Drosophila NIP, a protein responsible for Numb recruitment to the plasma membrane during asymmetric cell division (30), showing 31% identical sequence and similar length (483 vs. 474 aa).

Duoxa1 variants tagged with a V5 epitope were stably expressed in the Flp-In 293 cell line, allowing selection of clones containing single gene copies integrated at the same genomic site. Western blot analysis of isogenic clones indicated Duoxa1α and Duoxa1β isoforms are more abundant proteins compared with γ and δ forms (Fig. 2A). Duoxa1β and Duoxa1δ forms appear as doublets and are smaller than α and γ, consistent with the absence of 45 aa and two predicted N-glycosylation sites in the first extracellular loop, due to the lack of the third coding exon. The Mr shifts observed after deglycosylation indicate that β and δ forms are incompletely glycosylated (∼2 kDa) and confirm that the α and γ forms (∼7 kDa) contain at least one more glycosylated asparagine residue (N84 or N109) in addition to N121 (residue numbers on α form). A polyclonal antiserum raised against an extracellular Duoxa1 peptide (residues 122–139) adjacent to N-glycosylation site N121 was used to assess tissue expression of the Duoxa1 isoforms. Interestingly, this antibody, which did not cross-react against Duoxa2 (Fig. 2B), could detect a band the same size as Duoxa1α in IL-13-induced primary human bronchial epithelial cells after N-glycosidase F treatment (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Detection of Duoxa1 protein variants. A) Western blot analysis of protein lysates (10 μg) extracted from stable Flp-In 293 clones expressing C-terminal V5-tagged proteins shows long forms (Duoxa1γ and Duoxa1δ) are produced less efficiently than short forms (Duoxa1α and Duoxa1β). Susceptibilities to endoglycosidase H (H) or N-glycosidase F (F) confirm N-glycosylation patterns proposed in Fig. 1C and indicate β and δ forms are incompletely glycosylated. B) Western blot analysis shows anti-Duoxa1 serum specificity for Duoxa1 but not Duoxa2. Protein extracts (10 μg) derived from Flp-In 293 cells transfected with empty, Duoxa1αV5, or Duoxa2V5 coding vector. Primary sera were diluted 1:500. C) Duoxa1 Western blot analysis (1:500) shows Duoxa1α is detected in IL-13-induced NHBE cells. Controls included protein lysates from Flp-In 293 stable clones expressing Duoxa1αV5 or Duoxa1γV5. Flp-In 293 (10 μg) and NHBE (75 μg) cell extracts were subjected to N-glycosidase F treatment prior to SDS-PAGE.

Subcellular localization of Duox isozymes and their maturation factors

Epitope tags introduced onto both Duox and the Duox maturation factors enabled efficient tracking of their intracellular trafficking and a comparison of activities relative to their expression levels. Insertion of the V5 epitope at either the amino or carboxyl terminus of Duoxa1α had no effect on protein levels detected or its ability to rescue Duox1 activity (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained with Duoxa1γ (not shown). Furthermore, the HA epitope added after the N-terminal signal peptide sequence (Ala21) of Duox1 had no effect on the levels of protein detected or on oxidase activities supported by coexpression of Duoxa1α when compared with untagged native Duox1 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Epitope tagging of Duox1 and Duoxa1 does not affect reconstitution of oxidase activity. A) Ionomycin-stimulated H2O2 production [10-min integrated relative fluorescence units (RFU)] from stable Flp-In 293 clones expressing HADuox1 protein, transiently transfected (48 h) with tagged and untagged Duoxa1α. Error bars reflect mean ± sd; data show a representative triplicate assay of 4 independent experiments. Right panel: corresponding Western blot analysis of expressed proteins (20 μg). B) Ionomycin-stimulated H2O2 production (10-min integrated RFU) from stable Flp-In 293 clones expressing Duoxa1αV5 protein, transiently transfected (48 h) with tagged and untagged Duox1 proteins. Error bars reflect mean ± sd; data show a representative triplicate assay of 3 independent experiments. Right panel: corresponding Western blot analysis of expressed proteins (20 μg).

Subcellular localization of Duoxa1 variants was explored by IF staining of Flp-In 293 Duoxa1V5 clones. The four Duoxa1 variants were detected after permeabilization, exhibiting identical staining patterns with the ER marker calnexin (Fig. 4A). Duoxa1 ER localization confirmed the endoglycosidase H deglycosylation results (Fig. 2A) revealing only N-linked ER-specific rich mannose motifs. In contrast, endogenous Duoxa1 was localized predominantly at the apical plasma membrane of human airway ciliated epithelial cells (Fig. 4B) when using the anti-Duoxa1 serum, suggesting additional components are required to target Duoxa1 to the cell surface.

Figure 4.

Transfected Duoxa1 is retained in the ER, whereas endogenous Duoxa1 localizes to the cell surface. A) IF staining of permeabilized stable Flp-In 293 clones expressing Duoxa1V5 variants resembles that of ER marker calnexin. B) IF staining of human tracheal sections shows Duoxa1 colocalizes with the apical plasma membrane marker ezrin along ciliated epithelial cells. Primary sera diluted 1:100.

Duoxa1β (Fig. 5A) and Duoxa1δ (not shown) did not rescue oxidase activity when coexpressed with Duox1. Furthermore, IF staining of stable Flp-In 293 clones coexpressing HADuox1 with either Duoxa1β or δ forms showed Duoxa and Duox colocalized within the ER (Fig. 5B) and no HADuox on the cell surface (Fig. 5C). In contrast, HADuox1 was targeted to the cell surface when coexpressed with Duoxa1α (Fig. 5C). These findings suggest the 45 aa encoded by the third exon, encompassing part of the second transmembrane domain and two N-glycosylation sites, are critical for restoration of Duox activity and its targeting to the plasma membrane.

Figure 5.

Duox1 is retained in the ER when coexpressed with Duoxa1β or δ. A) Ionomycin-stimulated H2O2 production (10-min integrated RFU) from stable Flp-In 293 clones expressing HADuox1 protein, transiently transfected (48 h) with tagged or untagged Duoxa1 proteins. Error bars reflect mean ± sd; data show a representative triplicate assay of 4 independent experiments. Right panel: corresponding Western blot analysis of expressed proteins (20 μg). B, C) IF staining of permeabilized (B) and unpermeabilized (C) stable DuoxaV5-HADuox Flp-In 293 clones.

We investigated targeting of the active Duoxa maturation factors coexpressed with Duox using stable isogenic Flp-In 293 clones transfected with a bicistronic DuoxaV5/HADuox cassette. Distinct IF staining was observed for each Duoxa/Duox pair (Fig. 6A). Duoxa1α/Duox2 and Duoxa2/Duox1 showed most prominent colocalization in the ER with calnexin. In the Duoxa1γ/Duox clones, both proteins appeared in the ER with calnexin, and in highly fluorescent vesicle-like structures that did not costain for calnexin. Interestingly, in cells expressing Duoxa1α/Duox1 and Duoxa2/Duox2 pairs, a distinct plasma membrane outline was observed for both proteins.

Figure 6.

Active Duox maturation factors are transported to the plasma membrane when coexpressed with Duox. A) IF staining of permeabilized stable DuoxaV5-HADuox Flp-In 293 clones reveals distinct localization patterns for each Duoxa variant. B) Cell surface IF staining of unpermeabilized HADuox1 or HADuox2 Flp-In 293 clones transiently transfected (48 h) with V5Duoxa coding vectors.

To confirm and extend our observations on cell surface targeting of Duox maturation factors, stable Flp-In 293 clones expressing HADuox protein were transiently transfected with N-terminal-tagged V5Duoxa coding vectors, allowing IF staining of surface-exposed proteins on unpermeabilized cells. Surprisingly, both Duox and Duoxa proteins colocalized on the plasma membrane in all six transfected Duoxa-Duox combinations examined (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained using a different N-terminal epitope tag on Duoxa1 in other transiently transfected cell models: COS-7 cells expressing FLAGDuoxa1α or γ along with HADuox1 transport both Duoxa1 and Duox1 to the plasma membrane, whereas FLAGDuoxa1β or δ isoforms were retained at the ER and did not support Duox1 transport to the plasma membrane (Fig. 7). In view of these and earlier findings, subsequent studies focused on the functional maturation factors, Duoxa2 and the Duoxa1α and γ isoforms, which differ within their C-terminal sequences.

Figure 7.

Active Duoxa1α/Duox1 and Duoxa1γ/Duox1 combinations translocate to the cell surface. A, B) IF staining of permeabilized (A) and unpermeabilized (B) COS-7 cells transiently cotransfected (48 h) with FLAGDuoxa1 and HADuox1 coding vectors. Pictures were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser-scanning microscope with an ×40 oil-immersion objective, NA 1.4. Anti-HA (MBL, Woods Hole, MA, USA) and anti-FLAG (Sigma) antibodies were diluted 1:1000. C) IF staining of untagged Duoxa1α, transiently expressed (48 h) in HADuox1 Flp-In 293 clone, detects Duox activator at the cell surface of unpermeabilized cells (left). When transiently expressed in Flp-In 293 cells, untagged Duoxa1α is not detected at the plasma membrane (right). Anti-Duoxa1 serum diluted 1:100.

To rule out the possibility that fused epitope tags on Duoxa1 (N- or C-terminal) would affect its localization in cells, we examined the subcellular targeting of untagged Duoxa1α using the anti-Duoxa1 serum. Figure 7C shows untagged Duoxa1α was also targeted to the plasma membrane but only when coexpressed with Duox1.

Cross-functioning of Duox with maturation factors

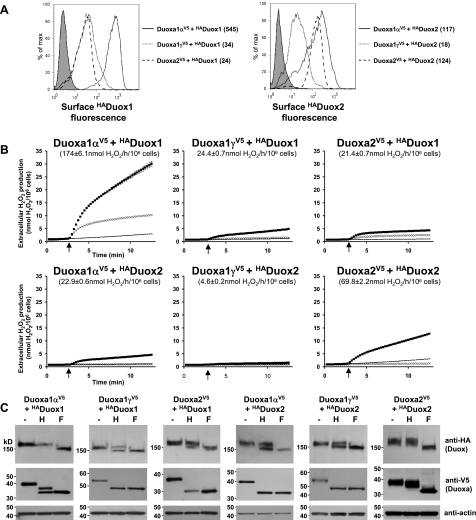

To quantify Duox surface expression and correlate it with oxidase function, flow cytometry experiments examined surface HADuox on intact cells (Fig. 8A). Duoxa1α was most efficient in delivering HADuox1 to the plasma membrane, while Duoxa1γ and Duoxa2 were significantly less capable of supporting Duox1 transport. Both Duoxa2 and Duoxa1α enabled efficient Duox2 plasma membrane delivery, although cells expressing the Duox2/Duoxa2 pair were more homogeneous. The Duox2/Duoxa1γ pair showed significantly lower surface-HA fluorescence. Assays of Duox oxidase reconstitution of the same cell lines based on extracellular H2O2 release confirmed that Duoxa1α is the preferred partner for rescuing Duox1 activity, consistent with its high surface exposure (Fig. 8B). However, Duox2 activity was not as tightly correlated with HADuox2 cell surface expression, since the Duox2/Duoxa2 pair exhibited substantially higher H2O2 release than Duox2/Duoxa1α pair. Interestingly, the most active lines coexpressing matched pairs (Duox1/Duoxa1α or Duox2/Duoxa2) exhibited activity even in the absence of ionomycin stimulation. Together these findings indicate Duoxa maturation factors can cross-function in enabling Duox plasma membrane transport, although specificity is evident in the higher levels of constitutive and stimulated oxidase activities reconstituted by matched Duox/Duoxa pairs.

Figure 8.

Duox maturation and reconstitution correlate with Golgi apparatus-based carbohydrate modifications on both Duox and Duoxa. A) Flow cytometric analysis of cell-surface-exposed HADuox on stable DuoxaV5-HADuox Flp-In 293 clones. Numbers indicate fluorescence geometric mean. Flp-In 293 clone stably transfected with HADuox1 was used as negative control (shaded peak). B) Ionomycin-stimulated (▪, ×) or unstimulated (−) H2O2 release by corresponding cloned lines in A. Oxidase activity was inhibited by preincubation (10 min) with 10 μM DPI (×). Arrow, 1 μM ionomycin stimulation. Error bars reflect mean ± sd of a representative triplicate assay. Activities in parenthesis derived from 3 experiments performed in triplicate. C) Western blot analysis of N-deglycosylation-treated protein lysates (10 μg) extracted from stable DuoxaV5-HADuox Flp-In 293 clones.

Parallel experiments examined Golgi-based carbohydrate modifications of Duox and the maturation factors, as indicators of their maturation and intracellular transport (Fig. 8C). Formation of endoglycosidase H-resistant forms of Duox1 and Duox2 correlated closely with oxidase reconstitution. Duox1 and Duox2 became completely endoglycosidase H resistant when coexpressed with Duoxa1α and Duoxa2, respectively. Moreover, in these efficiently reconstituted lines the maturation factors also acquired endoglycosidase H resistance. Cells expressing other Duox/Duoxa pairs exhibiting lower oxidase activities showed only partial processing of Duox into endoglycosidase H-resistant proteins and no processing of the maturation factors. Thus, Golgi-based carbohydrate modifications of Duox and their corresponding maturation factors are better correlated with Duox reconstitution than Duox cell surface expression alone.

Specificity of reactive oxygen species released by plasma membrane Duox/Duoxa complexes

Recent studies indicated that Duoxa1 can cross-function in rescuing Duox2 activity; however, the reconstituted oxidase appeared to produce O2·− as the predominant reactive oxygen species (21). Therefore, we examined O2·− release in each of the reconstituted lines by two independent assays (Fig. 9A, B). Duox2 reconstituted with Duoxa1α or γ produced significant O2·− levels, despite the low H2O2 output. In contrast, the matched pairs Duox1/Duoxa1α and Duox2/Duoxa2 that exhibit high cell surface expression and release high amounts of H2O2 did not produce O2·−. Cells coexpressing Duox1 with either Duoxa2 or Duoxa1γ did not produce any detectable O2·− release (not shown). Thus, it appears that Duox1 and Duox2 are intrinsically different in the reactive oxygen species they generate in the presence of various maturation factors.

Figure 9.

Duox maturation factors affect specificity of reactive oxygen species generation and form stable complexes with Duox on cell surface. A) Kinetics of extracellular O2·− release by Diogenes-based luminescence assay (RLU, relative luminescence unit) following 1 μM ionomycin stimulation (arrow) from stable DuoxaV5-HADuox Flp-In 293 clones. Error bars reflect mean ± sd of a representative triplicate assay of 3 independent experiments. B) Bar graph comparing extracellular O2·− release activities from stable DuoxaV5-HADuox Flp-In 293 clones detected by Diogenes (10 min integrated RLU; ▪) from A and cytochrome c reduction (10 min assay; □) shows O2·− production by cross-functioning Duoxa1α or γ /Duox2 pairs. Activities represent means of 3 experiments performed in triplicate. C) Western blot analysis does not detect Duoxa1α and Duoxa1γ immunoprecitated in a complex with surface-exposed HADuox2. Stable DuoxaV5-HADuox Flp-In 293 clones were incubated 30 min at 4°C with anti-HA before lysis. Surface [anti-HA-HADuox] complexes were then immunoprecipitated (HA-IP) with protein G Sepharose beads from total lysates (Tot). Negative controls included Flp-In 293 cells stably expressing either Duoxa1αV5 or HADuox1 alone. Data show representative results from one of three experiments.

To investigate whether the maturation factors could function as part of a catalytic complex, we examined Duoxa complex formation with HADuox immunoprecipitated from the cell surface (Fig. 9C). Surface-exposed HADuox1 or HADuox2 on intact cells was bound with anti-HA antibodies and then precipitated from detergent-lysed cell preparations. Western blot analysis showed the amounts of HADuox1 and Duox2 detected in these precipitates were consistent with cell surface expression detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 8). Stable Duoxa1αV5 and Duoxa1γV5 complexes were observed in immunoprecipitates with surface-exposed HADuox1, but not with HADuox2. Duoxa2 appeared to be tightly associated with either HADuox1 or 2. These findings suggest that the formation of stable Duox-Duoxa complexes in the plasma membrane has a role in the specificity of reactive oxidants produced by these oxidases.

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide the basis for a paradigm shift in which Duox maturation factors not only function as resident-ER proteins that are needed to export Duox beyond the ER and reconstitute oxidase activity on the cell surface. We show that the maturation factors can function by forming stable complexes with Duox, which affects the efficiency by which both proteins are processed in the Golgi apparatus and that they may even function as part of the H2O2-generating enzyme. In the same sense, p22phox can be viewed as a “maturation factor” for Nox 1, 2, 3, or 4, as it forms stable heterodimeric complexes with these core oxidase proteins and affects their stability, post-translation processing, subcellular targeting, and function as oxidant-generating enzymes (31,32,33,34). We provide several lines of evidence to suggest that the Duox maturation factors, when coexpressed with Duox, are not retained as ER resident proteins: 1) Duoxa1 is detected on the apical plasma membrane of the human tracheal epithelial layer, where Duox accumulates and secretes H2O2 into the airway lumen (13); 2) we detect both Duox and the maturation factors on the PM in several transfected cell models, using any combination of Duox and the active Duoxa isoforms identified; 3) under conditions of optimum Duox reconstitution (coexpressing matched Duox/Duoxa pairs), we observed efficient Golgi-based carbohydrate modifications in both Duox and the maturation factors; and 4) the matched Duox/Duoxa pairs producing high amounts of H2O2 and no detectable superoxide can be coprecipitated as stable complexes from the cell surface. In contrast, with cross-functioning Duox/Duoxa pairs, these proteins were less efficiently processed and transported to the plasma membrane, they do not form stable complexes, and the oxidases appear to leak superoxide, while producing less H2O2. Thus, the maturation factors may have a catalytic role in the plasma membrane-bound oxidase complexes.

It is not clear why previous work has not detected Duoxa2 on the cell surface, leading to the suggestion that this protein functions solely as a necessary and sufficient cofactor that allows Duox exit from the ER and subsequent processing into an active plasma membrane-targeted oxidase (20). These investigators later demonstrated that Duoxa2 does form a transient complex with Duox2 in the ER, but this association did not appear to persist beyond the ER (35). We explored several variables that could influence subcellular targeting or detection of the maturation factors on the plasma membrane, including the insertion of different peptide epitope sequences (FLAG and V5), their sites of fusion with Duoxa (N-terminal and C-terminal), different transfected hosts (HEK-293 and COS-7), and transfection protocols (transient and stable). None of these variables appear to inhibit targeting of the maturation factors along with Duox, and even the native epitope of untagged Duoxa1α was detected on the cell surface with Duox1. Their detection on the plasma membrane was favored by high, stable expression and use of extracellular, N-terminal epitopes that did not require detergent permeabilization of cells before staining. The GFP/myc-tagged Duoxa2 used by others may be too large or unstable to detect the intact protein at the plasma membrane.

We identified two alternative splicing events occurring during DUOXA1 mRNA processing that result in production of four different transcripts. DUOXA1β and δ, did not reconstitute active Duox, as both Duox and these splice variants remain within the ER. In contrast, Duoxa1α and γ isoforms, close homologues of Duoxa2 and Drosophila Numb-interacting protein, respectively, are capable of rescuing active Duox to the cell surface. However, these two competent maturation factors display unique features, suggesting they may target active Duox to distinct subcellular compartments: Duoxa1α enables efficient plasma membrane delivery of Duox1, whereas Duoxa1γ directs Duox1 to accumulate within vesicular stores, as well as the plasma membrane. Furthermore, no endoglycosidase H-resistant Duoxa1γ forms were detected when coexpressed with Duox1. Thus, Duox/Duoxa complexes may transit through different subcellular compartments where they could be subject to distinct regulatory mechanisms, including responsiveness to certain agonists or the availability of free calcium. Both the sites and amounts of H2O2 produced may regulate different Duox-dependent functions, including wound healing (cell migration, intracellular signaling) (36), thyroid hormone synthesis (3,4,5), acid secretion (18), or mucosal host defense (7). The site where Duox becomes a functional oxidase remains unknown, i.e., before or after reaching the plasma membrane (37). Future work should explore whether induction of some DUOXA variants dictates targeting of these reactive oxygen species generators to specific cell compartments.

The Nox family NADPH oxidases catalyze reduction of extracytosolic molecular oxygen into O2·− using cytosolic NADPH as an electron donor. Our study confirms that despite efficient targeting of Duox to the cell surface, the optimally reconstituted oxidases release no detectable O2·−, but generate specifically H2O2. The designation of Duox1 and Duox2 as “dual oxidases” was based on the presence of the extracellular oriented peroxidase-like domain in addition to their Nox-like NADPH oxidase core. However, there was no detectable peroxidase activity in our surface-exposed active enzymes, as all our assays of H2O2 release were completely dependent on exogenously added hemoperoxidase (HRP). Indeed, in the absence of HRP, we were unable to detect oxidation of several substrates, including tyrosine, homovanillic acid, 3-aminophthalhydrazide (luminol) or 10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine (Amplex Red) (data not shown). Consistent with our findings, Duox sequence comparisons with hemoperoxidases (thyro-, myelo-, lacto-, eosinoperoxidase) indicate that most of the highly conserved residues involved in heme binding are absent in the mammalian Duox ectodomains (10, 38). Thus, the Duox ectodomain appears to be responsible for the specific production of H2O2 (from O2·−) rather than H2O2 utilization, although the mechanism involved remains unclear. O2·− formation by the Duox Nox-like portions is a likely reactive intermediate leading to H2O2 formation, since we detected inadvertent release of O2·− from clones coexpressing Duox2/Duoxa1 cross-functioning pairs. However, endogenous Duox in thyroid and lung cells appears to be a dedicated H2O2 generator (7, 13,14,15). Moreover, thyroperoxidase, which is dependent on Duox-derived H2O2, is inhibited by O2·− (39). Future work is needed to define precisely how the Duox maturation factors affect the reactive oxygen species generated by Duox, whether it participates directly in the catalytic mechanism or simply supports optimum post-translational processing of the Duox ectodomain that may be involved directly in conversion of O2·− to H2O2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr. F. Borrego (NIAID/LIG) and Dr. J. Kabat (NIAID/RTB) for their technical assistance in flow cytometry and imaging experiments. This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and KAKENHI on Priority Areas and on the Global-COE Program in Japan.

References

- Donko A, Peterfi Z, Sum A, Leto T, Geiszt M. Dual oxidases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:2301–2308. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy C, Ohayon R, Valent A, Noel-Hudson M S, Deme D, Virion A. Purification of a novel flavoprotein involved in the thyroid NADPH oxidase. Cloning of the porcine and human cdnas. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37265–37269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deken X, Wang D, Many M C, Costagliola S, Libert F, Vassart G, Dumont J E, Miot F. Cloning of two human thyroid cDNAs encoding new members of the NADPH oxidase family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23227–23233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J C, Bikker H, Kempers M J, van Trotsenburg A S, Baas F, de Vijlder J J, Vulsma T, Ris-Stalpers C. Inactivating mutations in the gene for thyroid oxidase 2 (THOX2) and congenital hypothyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:95–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigone M C, Fugazzola L, Zamproni I, Passoni A, Di Candia S, Chiumello G, Persani L, Weber G. Persistent mild hypothyroidism associated with novel sequence variants of the DUOX2 gene in two siblings. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:395. doi: 10.1002/humu.9372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela V, Rivolta C M, Esperante S A, Gruneiro-Papendieck L, Chiesa A, Targovnik H M. Three mutations (p.Q36H, p.G418fsX482, and g.IVS19–2A>C) in the dual oxidase 2 gene responsible for congenital goiter and iodide organification defect. Clin Chem. 2006;52:182–191. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.058321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiszt M, Witta J, Baffi J, Lekstrom K, Leto T L. Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources supporting mucosal surface host defense. FASEB J. 2003;17:1502–1504. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1104fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J L, Creton R, Wessel G M. The oxidative burst at fertilization is dependent upon activation of the dual oxidase Udx1. Dev Cell. 2004;7:801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy C, Pomerance M, Ohayon R, Noel-Hudson M S, Deme D, Chaaraoui M, Francon J, Virion A. Thyroid oxidase (THOX2) gene expression in the rat thyroid cell line FRTL-5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;277:287–292. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens W A, Sharling L, Cheng G, Shapira R, Kinkade J M, Lee T, Edens H A, Tang X, Sullards C, Flaherty D B, Benian G M, Lambeth J D. Tyrosine cross-linking of extracellular matrix is catalyzed by Duox, a multidomain oxidase/peroxidase with homology to the phagocyte oxidase subunit gp91phox. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:879–891. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper R W, Xu C, McManus M, Heidersbach A, Eiserich J P. Duox2 exhibits potent heme peroxidase activity in human respiratory tract epithelium. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5150–5154. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross A R, Segal A W. The NADPH oxidase of professional phagocytes–prototype of the NOX electron transport chain systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1657:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forteza R, Salathe M, Miot F, Conner G E. Regulated hydrogen peroxide production by Duox in human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:462–469. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0302OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameziane-El-Hassani R, Morand S, Boucher J L, Frapart Y M, Apostolou D, Agnandji D, Gnidehou S, Ohayon R, Noel-Hudson M S, Francon J, Lalaoui K, Virion A, Dupuy C. Dual oxidase-2 has an intrinsic Ca2+-dependent H2O2-generating activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30046–30054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy C, Virion A, Ohayon R, Kaniewski J, Deme D, Pommier J. Mechanism of hydrogen peroxide formation catalyzed by NADPH oxidase in thyroid plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3739–3743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillou B, Dupuy C, Lacroix L, Nocera M, Talbot M, Ohayon R, Deme D, Bidart J M, Schlumberger M, Virion A. Expression of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (ThoX, LNOX, Duox) genes and proteins in human thyroid tissues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3351–3358. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hassani R A, Benfares N, Caillou B, Talbot M, Sabourin J C, Belotte V, Morand S, Gnidehou S, Agnandji D, Ohayon R, Kaniewski J, Noel-Hudson M S, Bidart J M, Schlumberger M, Virion A, Dupuy C. Dual oxidase2 is expressed all along the digestive tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G933–G942. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00198.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer C, Machen T E, Illek B, Fischer H. NADPH oxidase-dependent acid production in airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36454–36461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Deken X, Wang D, Dumont J E, Miot F. Characterization of ThOX proteins as components of the thyroid H2O2-generating system. Exp Cell Res. 2002;273:187–196. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasberger H, Refetoff S. Identification of the maturation factor for dual oxidase. Evolution of an eukaryotic operon equivalent. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18269–18272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600095200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamproni I, Grasberger H, Cortinovis F, Vigone M C, Chiumello G, Mora S, Onigata K, Fugazzola L, Refetoff S, Persani L, Weber G. Biallelic inactivation of the dual oxidase maturation factor 2 (DUOXA2) gene as a novel cause of congenital hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:605–610. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxen S, Belinsky S A, Knaus U G. Silencing of DUOX NADPH oxidases by promoter hypermethylation in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1037–1045. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:953–971. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer E L. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benard B, Brault J. Production of peroxide in the thyroid. Union Med Can. 1971;100:701–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiszt M, Kopp J B, Varnai P, Leto T L. Identification of renox, an NAD(P)H oxidase in kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8010–8014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130135897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick E, Mizel D. Rapid microassays for the measurement of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production by macrophages in culture using an automatic enzyme immunoassay reader. J Immunol Methods. 1981;46:211–226. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(81)90138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross A R, Jones O T. The effect of the inhibitor diphenylene iodonium on the superoxide-generating system of neutrophils. Specific labelling of a component polypeptide of the oxidase. Biochem J. 1986;237:111–116. doi: 10.1042/bj2370111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Regulation of translation in eukaryotic systems. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:197–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.001213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H, Percival-Smith A, Li C, Jia C Y, Gloor G, Li S S. A novel transmembrane protein recruits numb to the plasma membrane during asymmetric cell division. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11304–11312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Marchal C C, Casbon A J, Stull N, von Lohneysen K, Knaus U G, Jesaitis A J, McCormick S, Nauseef W M, Dinauer M C. Deletion mutagenesis of p22phox subunit of flavocytochrome b558: identification of regions critical for gp91phox maturation and NADPH oxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30336–30346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueyama T, Geiszt M, Leto T L. Involvement of Rac1 in activation of multicomponent Nox1- and Nox3-based NADPH oxidases. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2160–2174. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2160-2174.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambasta R K, Kumar P, Griendling K K, Schmidt H H, Busse R, Brandes R P. Direct interaction of the novel Nox proteins with p22phox is required for the formation of a functionally active NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45935–45941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Banfi B, Jesaitis A J, Dinauer M C, Allen L A, Nauseef W M. Critical roles for p22phox in the structural maturation and subcellular targeting of Nox3. Biochem J. 2007;403:97–108. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasberger H, De Deken X, Miot F, Pohlenz J, Refetoff S. Missense mutations of dual oxidase 2 (DUOX2) implicated in congenital hypothyroidism have impaired trafficking in cells reconstituted with DUOX2 maturation factor. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1408–1421. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley U V, Bove P F, Hristova M, McCarthy S, van der Vliet A. Airway epithelial cell migration and wound repair by ATP-mediated activation of dual oxidase 1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3213–3220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Driessens N, Costa M, De Deken X, Detours V, Corvilain B, Maenhaut C, Miot F, Van Sande J, Many M C, Dumont J E. Roles of hydrogen peroxide in thyroid physiology and disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3764–3773. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Fenna R E. X-ray crystal structure of canine myeloperoxidase at 3 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:185–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara M, Sugawara Y, Wen K, Giulivi C. Generation of oxygen free radicals in thyroid cells and inhibition of thyroid peroxidase. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002;227:141–146. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.