Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Over the past several years, colonic stenting has been advocated as an alternative to the traditional surgical approach for relieving acute malignant left-sided colonic obstruction. The aim of the present study was to determine the most cost-effective strategy in a Canadian setting.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

A decision analytical model was developed to compare three competing strategies: CS – emergent colonic stenting followed by elective resective surgery and reanastomosis; RS – emergent resective surgery followed by creation of either a diverting colostomy or primary reanastomosis; and DC – emergent diverting colostomy followed by elective resective surgery and reanastomosis. The costs were estimated from the perspective of the Manitoba provincial health plan.

RESULTS:

The use of CS resulted in fewer total operative procedures per patient (mean CS 1.03, RS 1.32, DC 1.9), lower mortality rate (CS 5%, RS 11%, DC 13%) and lower likelihood of requiring a permanent stoma (CS 7%, RS 14%, DC 14%). CS is slightly more expensive than DC, but less costly than RS (DC $11,851, CS $13,164, RS $13,820). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio associated with the use of CS versus DC is $1,415 to prevent a temporary stoma, $1,516 to prevent an additional operation and $15,734 to prevent an additional death.

CONCLUSIONS:

Colonic stenting for patients with acute colonic obstruction secondary to a resectable colonic tumour is comparable in cost with surgical options, and reduces the likelihood of requiring both temporary and permanent stomas. Colonic stenting should be offered as the initial therapeutic modality for Canadian colorectal cancer patients presenting with acute obstruction as a bridge to definitive RS.

Keywords: Bowel obstruction, Colon cancer, Colonic stenting, Cost-effectiveness

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Depuis quelques années, l’endoprothèse colique (EC) est préconisée au lieu de la démarche chirurgicale classique pour soulager une occlusion colique gauche maligne et aiguë. La présente étude vise à déterminer la stratégie la plus rentable au Canada.

PATIENTS ET MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Un modèle analytique décisionnel a été mis au point pour comparer trois stratégies concurrentes : une EC émergente suivie d’une résection chirurgicale (RC) non urgente et d’une réanastomose, une RC émergente suivie de la création d’une colostomie de dérivation (CD) ou d’une réanastomose primaire ou une CD émergente suivie d’une RC non urgente et d’une réanastomose. Les coûts ont été estimés d’après le régime d’assurance-maladie de la province du Manitoba.

RÉSULTATS :

Le recours à l’EC a favorisé un moins grand nombre d’opérations par patient (moyenne d’EC de 1,03, de RC de 1,32 et de CD de 1,9), un taux de mortalité plus faible (EC de 5 %, RC de 11 %, CD de 13 %) et une diminution de la probabilité de stomie permanente (EC de 7 %, RC de 14 %, CD de 14 %). L’EC est légèrement plus coûteuse que la CD, mais moins coûteuse que la RC (CD : 11 851 $, EC : 13 164 $, CD : 13 820 $). Le ratio coût-efficacité incrémentiel associé à l’usage de l’EC plutôt que de la CD est de 1 415 $ pour prévenir une stomie temporaire, de 1 516 $ pour prévenir une opération supplémentaire et de 15 734 $ pour prévenir un décès supplémentaire.

CONCLUSIONS :

Le coût de l’EC pour les patients atteints d’une occlusion colique aiguë secondaire à une tumeur colique pouvant être réséquée est comparable aux options chirurgicales en matière de coût, et cette intervention réduit la probabilité de recourir à une stomie temporaire ou permanente. L’EC devrait être offerte à titre de modalité thérapeutique initiale aux patients canadiens atteints d’un cancer colorectal ayant une occlusion aiguë, en attendant la RC définitive.

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in Canada (1). Up to one-third of patients with colorectal cancer develop colonic obstruction (2,3). Although many patients with acute colonic obstruction secondary to a colonic malignancy are found to have metastatic or otherwise unresectable disease, a significant proportion have lesions, which are amenable to resective surgery.

Until recently, the surgical approach has generally involved an emergent operation with creation of a temporary colostomy for proximal decompression and resection of the tumour either performed simultaneously (Hartmann’s procedure) or at a subsequent operation following recovery from the initial operation. Uncommonly, a primary anastomosis is performed at the time of the initial surgery, obviating the need to create a stoma. This is associated with a higher risk of anastomotic dehiscence among other surgical complications (4–6). Thus, the majority of patients receive a stoma and endure wait times from weeks to months before the colostomy can be reversed and bowel continuity restored (7,8). This can be associated with a lower mean health-related quality of life (3,9,10). Many patients with advanced age and comorbid conditions do not undergo restorative second surgery, thus leaving these patients with a permanent stoma (3). Moreover, performing any colonic surgery in the emergency setting can be associated with a mortality rate of approximately 10%, regardless of the approach used (3,11–14).

Colonic stenting is a relatively new therapeutic modality which has been advocated as a ‘bridge to surgery’ in the setting of acute colonic obstruction. The stent is used to relieve the obstruction, thus allowing the subsequent definitive resection and anastomosis in an elective setting (15). Placement of a colonic stent avoids the need for creation of diverting stomas, which may lead to a reduction in the length of hospital stay, as well as the number of surgeries required by any patient (16,17). Mortality rates for electively performed colonic surgery are significantly lower than similar operations performed on an emergency basis. However, stenting of the obstructing tumour may not always be technically successful or may be associated with significant complications, including bleeding, stent migration and colonic perforation. The stenting apparatus is also expensive and requires placement by physicians with specialized training.

There have been no prospective, randomized, controlled trials in potentially curable patients comparing emergent colonic stenting with surgery for the management of acute, malignant colonic obstruction. A recent decision analysis (18) performed by two of the authors of the current study, using costs from the perspective of a third-party payer in the United States, suggested that colonic stenting is both less expensive and more effective than performing an emergency Hartmann’s procedure over a wide range of assumptions. However, these findings may not be relevant in the Canadian health care system with lower per diem hospital costs and longer wait times for elective surgeries. Therefore, we decided to modify the model and perform a decision analysis based on Canadian costs and practices.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The analytical model used in the present study is a modification of the model created by the authors. This model was amended to account for differences in both the costs and the process of care between the United States and Canada for patients presenting with acute colonic obstruction. The model was created using the software TreeAge Pro 2005 (TreeAge Software, USA). Three strategies were compared for the management of patients with acute, malignant colonic obstruction:

Resective surgery strategy (RS), consisting of the emergent resection of the primary tumour, followed by creation of a diverting colostomy or performance of a primary anastomosis in selected subjects.

Emergency diverting colostomy surgery strategy (DC), consisting of the emergent creation of a diverting colostomy, followed by elective resective surgery of the tumour and primary anastomosis of the colon.

Emergent colonic stenting strategy (CS) consisting of colonic stenting, followed by elective resective surgery of the obstructing tumour.

Base case patient

The base case patient was a 70-year-old individual with significant yet nonterminal medical comorbidities who presented with acute colonic obstruction and was found on an urgently performed computed tomography (CT) scan to have a left colonic mass located proximal to the rectum, dilation of the proximal colon and no evidence of metastatic disease. The lesion was thought to be amenable to curative RS based on its appearance at CT scan.

Competing strategies

RS: In this strategy, the surgeon first attempts a one-stage resection with primary anastomosis. There is a 4% risk of developing an anastomotic leak, which requires another operation to take down the anastomosis and create a temporary colostomy (19,20). After emergency resection, the patient remains in the intensive care unit (ICU) for two days and then another 12 days in the surgical ward (3,21,22). Development of an anastomotic leak requires an additional three-day stay in the ICU.

It is assumed that the one-stage resection with primary anastomosis is not feasible in 41% of the cases such that a Hartmann’s procedure is performed. This consists of a resection of the colonic tumour with diversion of the proximal colon to a colostomy. Closure of the colostomy and reanastomosis of the remaining colon is performed eight weeks following the initial surgery. It is assumed that there is a 25% chance that a patient would not undergo colostomy closure and reanastomosis due to the presence of severe comorbid illness (3). Performance of colostomy closure and secondary reanastomosis is associated with an eight-day hospital stay.

There is a 5% chance of the patient having unresectable or metastatic disease that was not detected on the initial abdominal CT scan. If metastatic disease is found at laparotomy, the tumour is left in situ and a permanent diverting colostomy will remain for palliation of obstruction.

DC: All patients in this strategy are taken immediately to the operating room to perform a diverting colostomy. The malignant lesion itself is not mobilized. Patients remain hospitalized for four days after completion of the diverting colostomy. After four weeks, these patients are readmitted for elective resective surgery and primary reanastomosis. If metastatic disease is found at laparotomy, the tumour is left in situ and the colostomy considered palliative. Patients remain in hospital for 10 days after elective resective surgery and primary anastomosis. It is assumed that all patients will have their colostomies reversed when they have elective resective surgery, eliminating the need for a third-stage procedure for the closure of the colostomy. As in the resective surgery strategy, if metastatic disease was found at laparotomy, the tumour is left in situ and the diverting colostomy will remain for palliation

CS: In this strategy, the patient undergoes an attempted placement of a colonic stent endoscopically across the site of obstruction under fluoroscopic guidance. If the stent placement is successful, the patient is discharged from the hospital after two days. Four weeks later, the patient is readmitted for an elective resective surgery of the colonic tumour plus performance of a colonic reanastomosis, which is associated with a 10-day hospital stay. It is assumed that stent placement would effectively relieve acute colonic obstruction in 88% of cases. If the initial emergency stent placement is unsuccessful, the patients undergo an emergency Hartmann’s procedure and then have the subsequent follow-up as described above for patients managed at presentation with a Hartmann’s procedure.

At the time of the elective surgery, there is a 5% chance of the patient having unresectable or metastatic disease that was not detected on the initial abdominal CT scan. If metastatic disease is found, the tumour is not resected, and the stent is left in situ for palliation. In this circumstance, the patient has a 25% chance of developing a stent-related complication, which is assumed to be a stent migration. Development of stent migration required admission to hospital for a mean hospital stay of four days for stent removal and placement of a new stent.

Time horizon

A relatively short time horizon of six months was chosen to evaluate the short-term outcomes, because the choice of the initial management strategy of acute colonic obstruction was unlikely to alter the long-term morbidity and mortality of the underlying malignancy and the comorbid conditions.

Data sources

An extensive review of the literature was performed to obtain the probability inputs for the present model (Table 1). Where there were significant variations in the probabilities of input variables, estimates that favour emergency surgery and therefore bias the model against the competing strategy of CS were selected.

TABLE 1.

Base case scenario probabilities

| Scenarios | Base case value (%) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical mortality | ||

| Emergency surgery (any) | 10.0 | 3,4,6,13,18 |

| Elective resection and primary anastomosis | 4.0 | 32–35 |

| Secondary reanastomosis | 1.0 | 3 |

| Probability of obtaining resection and primary anastomosis on the emergent basis | 59.0 | 6,35 |

| Probability of secondary reanastomosis after emergency Hartmann’s procedure | 75.0 | 3,18 |

| After a negative computed tomography of the abdomen, probability of finding unresectable disease on laparotomy | 5.0 | 18 |

| Colonic stent placement | ||

| Clinical success | 88.0 | 36 |

| Uncomplicated clinical failure | 8.0 | 18 |

| Perforation rate | 3.5 | 36 |

| Procedure-related death | 0.5 | 36,37 |

| Rate of obstruction or migration of the colonic stent over six months | 24.0 | 36 |

Costs

In the Canadian single-payer health system, the direct costs of health care are borne by the provincial government health plan. In the present study, the costs were estimated from the perspective of the Manitoba’s provincial health plan, whose reimbursement rates are close to the mean of all Canadian provinces. Costs and reimbursements for physician services were obtained from the 2004 Manitoba Health Services Insurance Plan Physician’s Manual (23). Costs of all inpatient hospital services and supplies, excluding physician fees, were obtained from the 1994 Cost List for Manitoba Health Services and were inflated to 2004 dollar values using the GDP price index inflator with a multiplicative factor of 1.207 (24). The Canadian GDP price index in 2004 was 20.7% higher compared with the GDP price index for 1994. The cost of the stent apparatus was obtained from the charges currently billed by its manufacturer (Boston Scientific Inc, Canada) to the Health Sciences Centre (Winnipeg, Manitoba), which is Manitoba’s largest tertiary care hospital. The average weekly costs of outpatient stoma care were obtained from the annual budget of the Manitoba Ostomy Program, which provides supplies for all ongoing stoma care in the province. The major cost inputs are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Major individual component costs ($CDN)

| Components | Cost |

|---|---|

| Surgeon’s fees for: | |

| Hartmann’s procedure | 900.00 |

| Primary resection with anastomosis | 900.00 |

| Secondary reanastomosis (subsequent to Hartmann’s) | 770.00 |

| Colostomy or cecostomy (independent procedure) | 450.00 |

| Laparotomy | 335.00 |

| Stent placement | 332.25 |

| Physician’s fees for: | |

| Initial surgical consult | 98.00 |

| Surgical inpatient follow-up visit | 16.50 |

| Surgical outpatient follow-up visit | 25.00 |

| Initial intensive care unit consult | 288.70 |

| Intensive care unit follow-up care | 144.53 |

| Emergency room visit | 61.10 |

| Per diem hospital cost (adjusted to 2004 using the GDP price index deflator): | |

| Initial presentation for colonic obstruction (RDRG 1483: major large bowel procedure with class A comorbidities) | 691.70 |

| Secondary reanastomosis (RDRG 1523: minor large bowel procedure with class A comorbidities) | 655.48 |

| Reobstruction of long-term stent (RDRG 1802: gastrointestinal obstruction with class B comorbidities) | 520.28 |

| Endoluminal colonic stent | 2,100.00 |

| Aggregate cost of stent placement (includes physician fees in addition to the cost of the stent) | 2,592.00 |

RDRG Refined diagnosis-related group

No cost discounting was performed, because discounting would have had little effect on overall costs due to the short time horizon of the analysis.

Outcomes

The clinical outcomes evaluated were overall mortality rate, number of operations required, proportion of patients requiring a temporary stoma and proportion of patients requiring a permanent stoma. Economic outcomes compared between strategies included cost per surgical death prevented, cost per permanent or temporary stoma avoided and cost per additional surgery avoided.

One-way and two-way sensitivity analyses were performed by varying the costs and probability estimates over a wide range of values. Threshold values that would lead to a change in the preferred strategy were calculated.

RESULTS

Costs

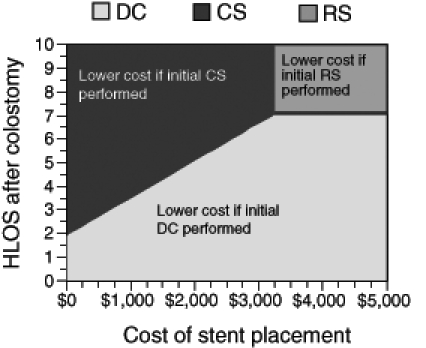

In the base case scenario, the strategy of performing initial colonic stenting was less expensive than performing emergency resective surgery, but was more costly than the strategy featuring an emergency diverting colostomy (Table 3). CS became the least expensive strategy when there was a 50% reduction in the cost of the stent placement or when the length of hospital stays after placement of a diverting colostomy increased from four to 6.1 days (Figure 1). When costs were considered only for those patients who survived the initial operation or procedure, the cost differential between the CS strategy and the DC strategy narrowed considerably (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Results of decision analysis

| Strategies | Cost ($CDN)

|

Mean number of operations per patient | Proportion with temporary stoma (%) | Proportion with permanent stoma (%) | Mortality (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Survivors only | |||||

| Emergency | ||||||

| Colonic stenting | 13,164.00 | 13,320.00 | 1.03 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Resective surgery | 13,820.00 | 14,846.00 | 1.32 | 44 | 14 | 11 |

| Diverting colostomy | 11,851.00 | 12,733.00 | 1.90 | 100 | 14 | 13 |

Figure 1).

Effect of cost ($CDN) of stent placement on the differential costs among the three strategies: colonic stenting (CS); diverting colostomy (DC) and resective surgery (RS). K One thousand; vs Versus

RS became less expensive than CS if more than 80% of patients who underwent RS were able to obtain a primary anastomosis at the time of tumour resection instead of a standard Hartmann’s procedure. Also, RS was less costly than CS if the cost of stent placement increased to $3,240, or if fewer than 50% of patients after a Hartmann’s procedure were able to undergo a second operation to reverse the colostomy and re-establish bowel continuity. RS is also less costly than CS if fewer than 70% of attempts at stent placement are successful. All of these scenarios were unlikely to be encountered in clinical practice. Figure 2 displays the effect of simultaneously varying of both the cost of the colonic stent apparatus and the length of hospital stay on the cost-effectiveness of the strategies.

Figure 2).

Two-way sensitivity analysis of both hospital length of stay (HLOS) and the cost ($CDN) of stent placement on the total cost of the competing strategies. CS Colonic stenting; DC Diverting colostomy; RS Resective surgery

Outcomes

Patients who were managed with the CS strategy had lower mortality rates, a lower mean number of operations per patient, and a lower probability of requiring a permanent or temporary stoma than either the RS or DC strategies (Table 3).

Stomas:

100% of patients managed with the DC strategy received a temporary stoma as part of their initial management, compared with 43% of those managed with RS and 7% of those managed with the CS strategy. Patients managed with the CS strategy required a stoma more frequently than those managed with the RS strategy, only when the rate of successful stent deployment fell below 26% or if all patients managed with RS had successful completion of a primary anastomosis following resection of the tumour (Figure 3A).

Figure 3).

A Effect of rate of successful stent deployment on the variance in the requirement of temporary colostomy with colonic stenting (CS) versus resective surgery (RS). More patients with CS required temporary stomas, when rate of stent deployment fell below 26%. B Effect of rate of successful stent deployment on the variance in the requirement of permanent colostomy. More patients with CS compared with RS or diverting colostomy (DC) required permanent stomas when the rate of stent deployment fell below 26%

There was only a 2% probability that a patient with the CS strategy was left with a permanent stoma, compared with 14% in either of the DC or RS strategies. The probability of successful stent deployment had to fall from 88% to a clinically improbable rate of 26% before a patient in the CS strategy was more likely to require a permanent stoma than patients managed with either the DC or RS strategy (Figure 3B).

Number of operations:

The DC strategy was associated with a higher mean number of operations than either of the RS or CS strategies. This relative relationship of the number of operations required with each of the comparative strategies persisted when a wide range of probabilities in the rates of primary anastomosis after resection, secondary reanastomosis after Hartmann’s procedure and successful stent deployment were evaluated using sensitivity analysis.

Mortality:

Mortality rates were lowest for patients managed with CS at 5%, compared with 11% and 13% for patients managed with RS and DC, respectively. The mortality rate associated with placement of an emergency colostomy had to fall below 1% for the DC strategy to be associated with a lower overall mortality rate than that associated with CS.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER)

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) refers to the additional cost associated with preventing one additional adverse outcome when a more expensive yet more effective strategy was utilized. The ICER for CS compared with DC is $1,415 to prevent a temporary stoma, $1,516 to prevent an operation, $10,791 to prevent a permanent stoma and $15,734 to prevent one additional death.

DISCUSSION

This analysis suggests that the use of colonic stenting for patients with acute, malignant colonic obstruction is less expensive than emergency resective surgery in Canadian patients. Furthermore, colonic stenting for acute malignant colonic obstruction was associated with lower mortality rates, a lower mean number of operations per patient, and a reduction in the number of permanent and temporary stomas required compared with either emergency resective surgery or emergency diverting colostomy. The superior efficacy of colonic stenting was maintained over a wide range of clinical scenarios as demonstrated in multiple sensitivity analyses. Though the cost associated with colonic stenting is higher than the cost of performing a diverting colostomy for the initial management of acute, malignant colonic obstruction, the incremental cost associated with providing one additional improved patient outcome is very reasonable.

Previously published cost-effectiveness analyses (17,25) have revealed results similar to our findings in the present study. In one analysis (25) performed using United Kingdom health care costs, preoperative colonic stenting resulted in a mean net savings of £685 per stented patient compared with performance of the Hartmann’s procedure, mainly due to a shorter length of hospital stay for stented patients. In the other analysis (17), surgical management of patients with acute colonic obstruction was 20% more expensive than initial colonic stenting and also required patients to stay in hospital for a greater number of days.

We assumed that all emergency operative procedures for acute, malignant colonic obstruction have similar mortality rates, irrespective of whether the tumour is resected or a diverting colostomy is performed alone. This is based on data from a randomized, controlled trial (11,26) in which the choice of initial surgery did not affect perioperative mortality rates for patients presenting with acute colonic obstruction secondary to malignancy. Similar rates have also been reported in non-randomized, retrospective, case series (3,27). However, surgeons may choose to perform a simple diverting colostomy in patients with more severe presentations, because this surgery can be completed more quickly than one that involves resection of the obstructing tumour. Therefore, the mortality rates seen with diverting colostomy in these studies may be more of a reflection of the increased clinical severity of patient presentation as opposed to a function of the type of surgery. Thus, the true mortality rate associated with performing a diverting colostomy in the emergency setting may be lower than our assumption in the base case analysis, and the mortality benefit seen with colonic stenting in place of performing an emergency diverting colostomy should be interpreted with caution.

In a sensitivity analysis in which we assumed that the mortality rate of performing a DC was equivalent to performing elective colonic tumour resection and primary anastomosis following colonic stenting, we found that performing an initial diverting colostomy costs approximately $430 less per patient than colonic stenting, compared with $1,300 in the base case scenario. This is because in our model, patients who died did so early in the course of management and did not accrue further downstream costs; thus, a strategy with an early, relatively high mortality rate appeared less costly and more cost-effective than a strategy with a low mortality rate. The cost of the stent apparatus needed to drop only to approximately $1,700 from its base case price of $2,100 for CS to become less costly than diverting colostomy in this situation.

In our study, we made a number of assumptions when the proper input into the model was uncertain; which has the effect of favouring initial surgical management. First, we assumed that all patients managed initially with placement of a diverting colostomy would have their colostomies reversed at the time of the surgical resection of their tumour. Several series (3,11,28–30) have described that a significant proportion of patients do not undergo reversal of their colostomies at the time of the tumour resection, but instead require a third surgery for re-establishment of bowel continuity. This third-stage surgery is often performed after several months, which is associated both with increased costs, as well as the potential for additional operative morbidity and mortality (3,28–31). Furthermore, as the costs were estimated from Manitoba’s provincial health plan, the indirect costs that patients themselves may bear through lost workplace productivity and decreased vitality due to longer stays in the hospital required for multiple operations were not considered. Moreover, we calculated our hospitalization costs in 2004 dollars by inflating available figures for the cost of hospitalization in 1994 according to the percentage change in the Canadian GDP between 1994 and 2004. There is little consensus as to which price index is optimal when adjusting for inflation in health care costs. In reality, costs in the health care sector have risen faster than prices in other sectors of the economy, and thus, we likely have underestimated the true cost of hospitalization in current dollars. This underestimation in costs likely led to an overestimation of the cost differential between the CS and DC strategies, as patients managed with diverting colostomy have longer hospital stays than those managed with the CS strategy. Even though all the assumptions described biased the model in favour of initial surgical management, management with initial placement of a colonic stent is only marginally more expensive than performing an emergency diverting colostomy, the least expensive of the surgical strategies.

We assumed that 59% of patients undergoing primary RS also received a primary anastomosis, thus obviating the need for a temporary colostomy. While this value was arrived at following a thorough review of the literature, the true probability of achieving a primary anastomosis following emergency resective surgery may be significantly lower. In spite of this possible bias of the model in favour of the RS strategy using a high estimate for the rate of primary anastomosis following resective surgery; resective surgery was still dominated by the CS strategy. In fact, primary reanastomosis would have to be feasible in almost all patients undergoing resective surgery for the RS strategy to surpass the outcomes achieved by CS. Conversely, decreasing the rate of primary reanastomosis both increases the average cost with RS strategy and is associated with increased requirements of stomas and number of surgeries, making the RS strategy even less preferable than in the base case analysis.

Although we did examine outcomes that undoubtedly affect health-related quality of life, we did not quantify the effect on health-related quality of life using quality-adjusted life years. To calculate quality-adjusted life years, one needs to be able to calculate the relative value of all of potential health states or health utilities for patients with acute colonic obstruction. To date, there are no published health utility values for these health states. However, it can be reasonably assumed that requiring additional operations or requiring a colostomy negatively affects health-related quality of life. Furthermore, it is exceedingly unlikely that a patient would prefer to undergo an operation that would require placement of a stoma if a management option was available that would obviate both the need for a stoma and was not associated with an increase in operative morbidity and mortality.

CONCLUSION

Emergency colonic stenting followed by elective surgery for patients presenting with potentially resectable, acute, malignant colonic obstruction results in the best overall outcome compared with any of the standard surgical approaches. This improvement in outcome by performing initial colonic stenting is less expensive than performing emergency resective surgery and is only slightly more expensive than placement of a diverting colostomy. We therefore recommend that physicians strongly consider colonic stenting as first-line management for patients with acute colonic obstruction as a bridge to definitive surgery.

Acknowledgments

Dr Laura Targownik is supported by the Rudy Falk Clinician Scientist Award. This work was funded by an unrestricted grant from Boston Scientific Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Cancer Institute of Canada: Canadian Cancer Statistics 2003<http://www.cancer.ca/vgn/images/portal/cit_776/61/38/56158640niw_stats_en.pdf> (Version current at April 1, 2006)

- 2.Riedl S, Wiebelt H, Bergmann U, Hermanek P., Jr [Postoperative complications and fatalities in surgical therapy of colon carcinoma. Results of the German multicenter study by the Colorectal Carcinoma Study Group] Chirurg. 1995;66:597–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deans GT, Krukowski ZH, Irwin ST. Malignant obstruction of the left colon. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1270–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biondo S, Pares D, Frago R, et al. Large bowel obstruction: Predictive factors for postoperative mortality. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1889–97. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer F, Marusch F, Koch A, et al. German Study Group “Colorectal Carcinoma (Primary Tumor)” Emergency operation in carcinomas of the left colon: Value of Hartmann’s procedure. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8(Suppl 1):s226–9. doi: 10.1007/s10151-004-0164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tekkis PP, Kinsman R, Thompson MR, Stamatakis JD, Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain, Ireland The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland study of large bowel obstruction caused by colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2004;240:76–81. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000130723.81866.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitry E, Barthod F, Penna C, Nordlinger B. Surgery for colon and rectal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:253–65. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearce NW, Scott SD, Karran SJ. Timing and method of reversal of Hartmann’s procedure. Br J Surg. 1992;79:839–41. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JJ, Del Pino A, Orsay CP, et al. Stoma complications: The Cook County Hospital experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1575–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02236210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nugent KP, Daniels P, Stewart B, Patankar R, Johnson CD. Quality of life in stoma patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1569–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02236209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kronborg O. Acute obstruction from tumour in the left colon without spread. A randomized trial of emergency colostomy versus resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10:1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00337576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuffy M, Abir F, Audisio RA, Longo WE. Colorectal cancer presenting as surgical emergencies. Surg Oncol. 2004;13:149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perrier G, Peillon C, Liberge N, Steinmetz L, Boyet L, Testart J. Cecostomy is a useful surgical procedure: Study of 113 colonic obstructions caused by cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:50–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02237243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guivarc’h M, Boche O, Roullet-Audy JC, Mosnier H. [Sixty-one cases of acute obstructions of the colon caused by cancer. Indications for emergency surgery] Ann Chir. 1992;46:239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron TH, Kozarek RA. Endoscopic stenting of colonic tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:209–29. doi: 10.1016/S1521-6918(03)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baque P, Chevallier P, Karimdjee SF, et al. [Colostomy vs self-expanding metallic stents: Comparison of the two techniques in acute tumoral left colonic obstruction] Ann Chir. 2004;129:353–8. doi: 10.1016/j.anchir.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binkert CA, Ledermann H, Jost R, Saurenmann P, Decurtins M, Zollikofer CL. Acute colonic obstruction: Clinical aspects and cost-effectiveness of preoperative and palliative treatment with self-expanding metallic stents – A preliminary report. Radiology. 1998;206:199–204. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.1.9423673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Targownik LE, Spiegel BM, Sack J, et al. Colonic stent vs. emergency surgery for management of acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: A decision analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:865–74. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koruth NM, Krukowski ZH, Youngson GG, et al. Intra-operative colonic irrigation in the management of left-sided large bowel emergencies. Br J Surg. 1985;72:708–11. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan SG, Nambiar R, Rauff A, Ngoi SS, Goh HS. Primary resection and anastomosis in obstructed descending colon due to cancer. Arch Surg. 1991;126:748–51. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410300094014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Santos C, Lobato RF, Fradejas JM, Pinto I, Ortega-Deballon P, Moreno-Azcoita M. Self-expandable stent before elective surgery vs emergency surgery for the treatment of malignant colorectal obstructions: Comparison of primary anastomosis and morbidity rates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:401–6. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smothers L, Hynan L, Fleming J, Turnage R, Simmang C, Anthony T. Emergency surgery for colon carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:24–30. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6492-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Government of Manitoba. Manitoba Physician’s Manual <http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/documents/physmanual.pdf> (Version current at April 1, 2006).

- 24.Jacobs P, Shanahan M, Roos NP, Farnworth M. Cost List for Manitoba Health Services. Winnipeg: Manitoba, Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and Evaluation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osman HS, Rashid HI, Sathananthan N, Parker MC. The cost-effectiveness of self-expanding metal stents in the management of malignant left-sided large bowel obstruction. Colorectal Dis. 2000:233–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2000.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Salvo GL, Gava C, Pucciarelli S, Lise M. Curative surgery for obstruction from primary left colorectal carcinoma: Primary or staged resection? Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD002101. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002101.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sjodahl R, Franzen T, Nystrom PO. Primary versus staged resection for acute obstructing colorectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1992;79:685–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khoury DA, Beck DE, Opelka FG, Hicks TC, Timmcke AE, Gathright JB., Jr Colostomy closure. Ochsner Clinic experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:605–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02056935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen F, Stuart M. The morbidity of defunctioning stomata. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:218–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosdell DM, Doberneck RC. Morbidity and mortality of ostomy closure. Am J Surg. 1991;162:633–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90125-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porter JA, Salvati EP, Rubin RJ, Eisenstat TE. Complications of colostomies. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:299–303. doi: 10.1007/BF02553484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mella J, Biffin A, Radcliffe AG, Stamatakis JD, Steele RJ. Population-based audit of colorectal cancer management in two UK health regions. Colorectal Cancer Working Group, Royal College of Surgeons of England Clinical Epidemiology and Audit Unit. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1731–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bokey EL, Chapuis PH, Fung C, et al. Postoperative morbidity and mortality following resection of the colon and rectum for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:480–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02148847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGregor JR, O’Dwyer PJ. The surgical management of obstruction and perforation of the left colon. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stamatakis JD, Thompson MR, Chave H. London: Association of Coloproctology of Great Britian and Ireland; 2000. National Audit of Bowel Obstruction Due to Colorectal Cancer April 1998–March 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sebastian S, Johnston S, Geoghegan T, Torreggiani W, Buckley M. Pooled analysis of the efficacy and safety of self-expanding metal stenting in malignant colorectal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2051–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dauphine CE, Tan P, Beart RW, Jr, Vukasin P, Cohen H, Corman ML. Placement of self-expanding metal stents for acute malignant large-bowel obstruction: A collective review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:574–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02573894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]