Abstract

Objective

This study examined the ability of five comonomer blends (R1-R5) of methacrylate-based experimental dental adhesives solvated with 10 mass% ethanol, at reducing the permeability of acid-etched dentin. The resins were light-cured for 20, 40 or 60 s. The acid-etched dentin was saturated with water or 100% ethanol.

Method

Human unerupted third molars were converted into crown segments by removing the occlusal enamel and roots. The resulting crown segments were attached to plastic plates connected to a fluid-filled system for quantifying fluid flow across smear layer-covered dentin, acid-etched dentin and resin-bonded dentin. The degree of conversion of the resins was measured using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy.

Result

Application of the most hydrophobic comonomer blend (R1) to water-saturated dentin produced the smallest reductions in dentin permeability (31.9, 44.1 and 61.1% after light-curing for 20, 40 or 60 s respectively). Application of the same blend to ethanol-saturated dentin reduced permeability of 74.1, 78.4 and 81.2%, respectively (p<0.05). Although more hydrophilic resins produced larger reductions in permeability, the same trend of significantly greater reductions in ethanol-saturated dentin over that of water-saturated dentin remained. This result can be explained by the higher solubility of resins in ethanol vs. water.

Significance

The largest reductions in permeability produced by resins were equivalent but not superior, to those produced by smear layers. Resin sealing of dentin remains a technique-sensitive step in bonding etch-and-rinse adhesives to dentin.

Keywords: dentin permeability, degree of conversion, hydrophilic resins, curing-time, ethanol-wet bonding

1. Introduction

The observation that resin-bonded dentin is not as well sealed as dentin covered with a smear layer [1-6] raises concerns as to whether dental adhesives can ever seal dentin as well as cementum or enamel. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) studies have shown that fluorescent tracers can pass between resin tags and the walls of acid-etched dentin [7-12]. This has been termed micropermeability. Apparently, there are nanometer-sized spaces that remain filled with water after resin infiltration or are the result of the solvent evaporation step, where more water is pulled from dentin into the bonded interface [13]. It is likely that the relatively low solvent concentrations (14-17 moles/L) and comonomer concentrations (ca. 2-3 moles/L) can not displace the high concentration (55.6 moles/L) of very small water molecules from rinsed, acid-etched collagen fibrils. Although it is known that >9% water lowers the percent conversion of adhesives [14], there are other issues that may play a role in attempts to seal dentin with solvated copolymers. All contemporary “simplified adhesives” whether used in etch-and-rinse or self-etch adhesive systems, contain mixtures of hydrophilic monomethacrylates and more hydrophobic dimethacrylates to permit sufficient cross-linking to make the adhesives strong enough to serve as bonding agents. Through careful formulation, the manufacturers add sufficient solvents to create a single phase solution. The goal is to have the hydrophilic and hydrophobic comonomers copolymerize with each other to create uniformly cross-linked copolymerized chains. However, when bonded resins are stained by ammoniacal silver nitrate and examined by transmission electron microscopy, the resin films are not homogeneous. Instead, they contain water-filled voids and channels called water trees [15]. We speculated that the resin films created by most simplified adhesives, when applied to moist dentin, create heterogeneous adhesive films due to sequestration of domains of hydrophobic stiff copolymers from domains of more flexible hydrophilic copolymers. Depending upon the relative concentrations of hydrophilic versus hydrophobic comonomers, the “matrix” of the film could be hydrophilic or hydrophobic. Regardless of the composition, we speculate that there will be hydrophilic regions in the film that span the entire thickness of the adhesive film. The boundaries between the hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains may contain microphase separations that are too small to be identified using conventional methods. What are called water-trees may represent the interfaces of these invisible phase boundaries. When miniature impressions are taken of resin films bonded to dentin, many such surfaces are covered with micrometer size water droplets [16-20]. We speculated that each water droplet is at the top of a water tree that makes these resin films permeable to water. Additional support for that idea was the high correlation between the hydraulic conductance of resin-bonded dentin and the number of water droplets per unit surface area on the surface of resin-bonded dentin [12].

Another reason why resin films are more or less permeable to water is due to their degree of conversion [21]. Under-cured adhesives are more permeable [21,22] than optimally-cured adhesives. Under-curing can be due to inadequate irradiation or due to dilution by too much solvent, inadequate solvent evaporation and other variables.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of different curing times using a quartz halogen light, on the permeability of resin-dentin bonds made with experimental model adhesives of increasing hydrophilicities to water or ethanol-saturated acid-etched dentin. The test null hypotheses were that the degree of conversion has no effect on the permeability of resin-bonded dentin and that the permeability of the experimental resins bonded to water-saturated dentin was no different than when bonded to ethanol-saturated dentin.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Teeth preparation

One hundred-fifty non-carious unerupted human third molars were collected after the patients’ informed consent had been obtained under a protocol reviewed and approved by the Human Assurance Committee of the Medical College of Georgia. Crown segments were prepared by sectioning the occlusal enamel and roots of each tooth, using a slow-speed diamond saw (Isomet, Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL, USA) under water-cooling. The pulpal tissue was removed with a pair of small forceps. Care was taken to avoid scratching or damaging the predentin. The dentin surface was further abraded with 240-grit silicon carbide paper, down to a residual dentin thickness of 0.6 ± 0.2 mm from the ground surface to the highest pulp horn. The crown segments were attached to Plexiglass slabs (1.8 × 1.8 × 0.7 cm) using a viscous cyanoacrylate cement (Zapit, Dental Ventures of America, Corona, CA, USA) which also covered the peripheral cementum. Each Plexiglass slab was penetrated by a short length of 18-gauge stainless steel tubing, which ended flush with the top of the slab. This tube permitted the pulp chamber to be filled with water and to be connected to a fluid-filled automated flow-recording device (Flodec System, De Marco Engineering, Geneva, Switzerland).

2.2 Experimental resins

Five light-curing versions of experimental adhesive resin blends (R1, R2, R3, R4 and R5) were investigated (Table 1). R1 and R2 are similar to nonsolvated hydrophobic resins used in the formulation of contemporary commercial bonding agents of three-step etch-and-rinse and two-step self-etch adhesives systems [23]. R3 is representative of a typical two-step etch-and-rinse adhesive [24], R4 and R5 contain methacrylate derivatives of carboxylic and phosphoric acids, respectively, which are very hydrophilic, and are similar to a one-step self-etch adhesive [24]. These resin blends, with known compositions and concentrations, were purposely formulated so that they could be ranked in an increasing order of hydrophilicity, based on their Hoy’s solubility parameters (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition of experimental resins 1-5 and Hoy’s solubility parameters (δ) for the comonomers and substrate

| Neat resin | Resin 90 mass% Ethanol 10 mass% | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resin # | Neat Resin Composition | δd | δp | δh | δt | δd | δp | δh | δt |

| R1 | 70 wt% BisADM 28.75 % TEGDMA |

15.0 | 10.3 | 6.6 | 19.4 | 14.8 | 10.4 | 7.9 | 19.7 |

| R2 | 70% BisGMA 28.75% TEGDMA |

15.9 | 12.4 | 6.9 | 21.2 | 15.6 | 12.3 | 7.9 | 21.3 |

| R3 | 70% BisGMA 28.75% HEMA |

15.6 | 13.0 | 8.5 | 22.1 | 15.3 | 12.9 | 9.7 | 22.2 |

| R4 | 40% BisGMA 30% TCDM 28.75% HEMA |

16.2 | 13.5 | 9.0 | 23.0 | 15.9 | 13.3 | 10.1 | 23.1 |

| R5 | 40% BisGMA 30% BisMP 28.75% HEMA |

15.1 | 13.5 | 11.1 | 23.1 | 14.9 | 13.2 | 12.0 | 23.2 |

| Water | 12.2 | 22.8 | 40.4 | 48.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Ethanol | 12.6 | 11.2 | 20.0 | 26.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| H2O-sat. matrix | 11.8 | 15.3 | 22.5 | 30.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| EtOH-sat. matrix | 12.0 | 12.5 | 18.1 | 25.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

Abbreviations: E-BisADM = etoxylated-BisPhenol A dimethacrylate; BisGMA = 2,2-bis[4-(2-hydroxy-3-methacryloylpropoxy)]-phenyl propane; TEGDMA = triethyleneglycol dimethacrylate; HEMA = 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate; TCDM = di(hydroxyethylmethacrylate)ester of 5-(2,5-dioxotetrahydrofurfuryl)-3-methyl-3-cyclohexane-1, 2’-dicarboxylic acid; BisMP = Bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl]phosphate. All solubility parameters were calculated using commercially available software (Computer Chemistry Consultancy <www.compchemconsul.com>. δd = Hoy’s solubility parameter for dispersive forces; δp = Hoy’s solubility parameter for polar forces; δh = Hoy’s solubility parameters for hydrogen bonding forces; δt = Hoy’s solubility parameter for total cohesive forces, equivalent to Hildebrand’s solubility parameter (δ). δt = [(δd)2 + (δp)2 + (δh)2]½. All Hoy’s values given in (MPa)½. All blends contained 1.0% 2-ethyl-4-aminobenzoate and 0.25% camphoroquinone.

Absolute ethanol (10% ethanol/90% resin mass%) was added to the resin blends simulating the formulation of lightly solvated dentin bonding system [25]. In a previous report [26], we found that resins 1 and 2 were too hydrophobic to permeate water-saturated dentin. However, by saturating acid-etched dentin with 100% ethanol instead of water, the hydrophobic resins 1 and 2 gave much higher bond strengths than were obtained on water-saturated dentin, because the resins were very soluble in ethanol. Accordingly, we included two substrate solvents, water vs. ethanol in the current study.

2.3 Bonding procedures

The dentin surfaces of the crown segments were acid-etched with 37% phosphoric acid gel (Etch 37, Bisco Inc., Schamburg, IL, USA) for 15 s and rinsed thoroughly with deionised water. In Group 1, the teeth were blot-dried to leave a water-moist surface just before bonding. In Group 2, teeth were treated with 100% ethanol delivered from a squeeze bottle to replace rinsing water with ethanol for 15 s. There were five resin subgroups (90 mass% R1-5/10% ethanol) within the two bonding surface groups. Two layers (approximately 20 μm thick) of solvated resin was applied to the demineralized dentin, visibly moist with either deionized water or 100% ethanol, under constant agitation for 30 s. Solvent evaporation was not performed as it was shown that 10% ethanol increased percent conversion of these resins [27]. A piece of Mylar film was placed over the top of the solvated comonomer mixture to exclude oxygen and then the adhesive resin was light-cured using an Optilux 501 halogen light-curing unit (Demetron/Kerr, Danbury, CT, USA) with a power output of 665 ± 6 mW/cm2 as measured using a laboratory radiometer (DAS2100, Labsphere, Sulton, NH, USA). The adhesive was then light-cured for 20, 40 or 60 s from a distance of 2 mm. Bonding was performed with the pulp chamber filled with water, but at zero hydrostatic pressure. There were 5 resins × 2 substrate solvents × 3 light-curing times = 30 cells with 5 teeth per cell = 150 teeth.

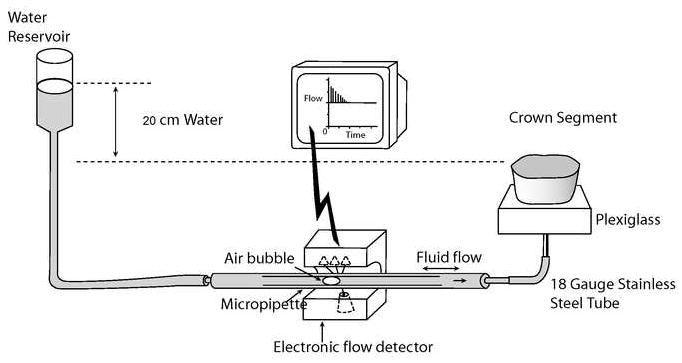

2.4 Permeability measurements

An in vitro fluid transport model was used to measure the fluid conductance induced by hydrostatic pressure, as described by Pashley and Depew [28]. Each crown-segment was connected via polyethylene tubing to the Flodec device (DeMarco Engineering, Geneva, Switzerland) under a constant physiological hydrostatic pressure (20 cm H2O). This pressure gradient between the water reservoir and the specimen induced fluid movement through the crown-segment (Fig. 1). The rate of fluid movement was measured by following the displacement of a tiny air bubble that was introduced into a glass capillary located between the water reservoir and the specimen (Fig. 1). Displacement of the air bubble was detected via a laser diode incorporated in the Flodec device. The linear displacement was automatically converted to a volume flow (μL min-1) via the computer software program. The numerical data was transferred to a spreadsheet, from which the mean values were calculated, following the protocol employed in previous studies [1,4,25]. The rate of fluid flow across dentin was measured sequentially three times as follows: 1) in the presence of the smear layer covering the dentin; 2) after etching the dentin surface with 37% phosphoric acid gel for 15 s for the determination of maximum baseline hydraulic conductance (Lp), and 3) after the bonding procedures [1]. All measurements were performed for 5-min intervals with the specimen covered with a large drop of water in order to prevent evaporative water flux [28]. For each specimen, fluid flow (μL min-1) across the smear layer-covered dentin, phosphoric-acid etched dentin and resin-bonded dentin were converted in Lp (μL min-1cm-2 cm H2O-1), by dividing the fluid flow (μL min-1) by the exposed dentin surface area of the specimen (cm2) and the water pressure (cm H2O, i.e. 20 cm H2O). The permeability results obtained from the smear layer-covered dentin and the resin-bonded dentin were expressed as percentages of the maximum permeability derived from the acid-etched dentin. This allowed each specimen to serve as its own control, since the same surface area was used in all three measurements [3,28,29].

Fig. 1.

Schematic of tooth preparation and apparatus used to measure the ability of experimental resins to seal water- vs. ethanol-saturated acid-etched dentin.

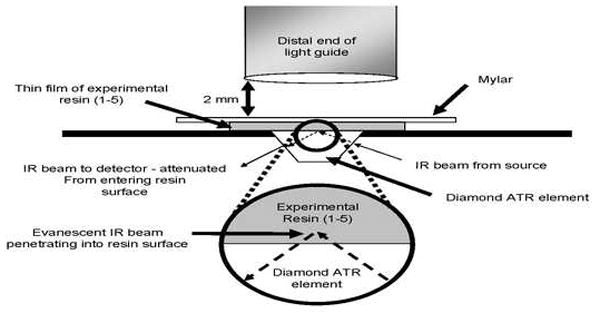

2.5 Degree of conversion measurement

The comonomer blends with different degrees of hydrophilicity (R1-R5) were solvated with absolute ethanol (10% ethanol/90% resin mass%). The solutions were stored in the dark at room temperature in labeled, opaque bottles until needed. One drop of each resin/solvent mixture was placed on the diamond crystal (Fig. 2) of a horizontal attenuated total reflectance (ATR) stage (Golden Gate Mk II, SPECAC Inc.,Woodstock, GA) using a disposable 1 mL syringe with a 27 ga. needle. The ATR was positioned in the optical compartment of a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTS-40, Digilab/Bio-Rad, Cambridge, MA). A piece of Mylar film was immediately placed over the top of the solvated comonomer mixture to exclude oxygen and prevent solvent evaporation. A quartz-tungsten-halogen light-curing unit (Optilux 501, Demetron/Kerr, Danbury, CT; power output of 665 mW/cm2) was used to provide 20, 40 or 60 s exposures. The light tip end was positioned 2 mm above and perpendicular to the surface of the Mylar strip (Fig. 2). The experimental setup simulated dispensing the model resin in a thin layer as it would be on a tooth surface clinically, but without air-drying. Infrared (IR) spectra were obtained between 4000 and 800 cm−1 at 2 cm−1 resolution. Spectral acquisition was initiated immediately upon resin droplet deposition to obtain the IR spectra of each solution group in the uncured state. The halogen curing light was then activated after 5 s. After the 20, 40 and 60 s exposures, any post-cure polymerization was allowed to continue up to 120 s from initiation of light to obtain the IR spectrum of the polymerized material. The percent monomer conversion was calculated using methods commonly found in the literature [30-34]. Basically, these methods compare changes in the ratio of aliphatic C=C absorption (1636 cm−1) to that of an internal standard (aromatic C=C at 1608 cm−1) in the cured and uncured states. Five repetitions for each test condition were made.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of light guide positioned over resin film on the diamond surface of an attenuated-total reflectance (ATR) element of a horizontally positioned FTIR spectrophotometer.

2.6 Statistic analysis

The percentage of the maximum fluid flow across smear layer-covered, acid-etched and resin-bonded dentin at 20 cm water pressure for the experimental resins were analyzed by a three-way ANOVA (resin, curing time, DC) and Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. FTIR data were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA to evaluate how the curing time influenced the DC. The degree of conversion among the tested materials was not statistically compared as they present different ratios of aliphatic to aromatic monomers (Dr. Frederick Rueggeberg, personal communication). The correlations between % fluid conductance of resin-bonded dentin and the degree of conversion of the polymerized neat and solvated resins were evaluated by means of regression analyses. Statistical significance was preset at α=0.05.

3. Results

With the acid-etched dentin permeability assigned a value of 100%, the permeability of smear layer-covered dentin was only about 7% of the acid-etched value (Table 2). The goal was to determine how well the experimental R1-5 could seal water- vs. ethanol-saturated acid-etched dentin compared to smear layer-covered dentin values.

Table 2.

Comparisons of residual permeability of dentin covered with smear layers vs. resin bonds

| 10/90 EtOH/resin wt% | Curing time (s) | Water-saturated | EtOH-saturated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smear layer | -- | 7.1 ± 2.0a | 7.0 ± 1.4a |

| Resin 1 | 20 | 68.1 ± 7.0d | 25.9 ± 6.2c |

| 40 | 55.9 ± 6.1d | 21.6 ± 7.0c | |

| 60 | 38.9 ± 5.3c | 18.8 ± 7.5c | |

| Smear layer | -- | 7.1 ± 1.6a | 7.1 ± 1.9a |

| Resin 2 | 20 | 23.1 ± 8.2c | 16.3 ± 3.5c |

| 40 | 18.9 ± 4.5c | 12.9 ± 3.9b | |

| 60 | 11.7 ±2.1b | 10.2 ± 4.2a | |

| Smear layer | -- | 7.1 ± 1.8a | 7.1 ± 1.7a |

| Resin 3 | 20 | 27.4 ± 7.3c | 17.8 ± 4.5c |

| 40 | 13.8 ± 1.9b | 10.8 ± 3.0a | |

| 60 | 11.0 ± 1.3b | 9.2 ± 1.8a | |

| Smear layer | -- | 7.1 ± 1.3a | 7.1 ± 2.0a |

| Resin 4 | 20 | 16.8 ± 5.8b | 13.1 ± 1.2b |

| 40 | 11.7 ± 4.3b | 9.7 ± 4.1b | |

| 60 | 8.3 ± 2.5a | 8.0 ± 2.6b | |

| Smear layer | -- | 7.1 ± 1.9a | 7.2 ± 2.0a |

| Resin 5 | 20 | 13.2 ± 2.4b | 10.9 ± 3.4b |

| 40 | 10.1 ± 2.8b | 7.4 ± 2.1a | |

| 60 | 7.2 ± 2.2a | 7.2 ± 0.9a |

Values are mean ± S.D. (n = 5) % residual permeability. Smear layer values represent the residual permeability created by smear layers alone, as a reference seal. Groups identified by different superscript letters are significantly different (p<0.05).

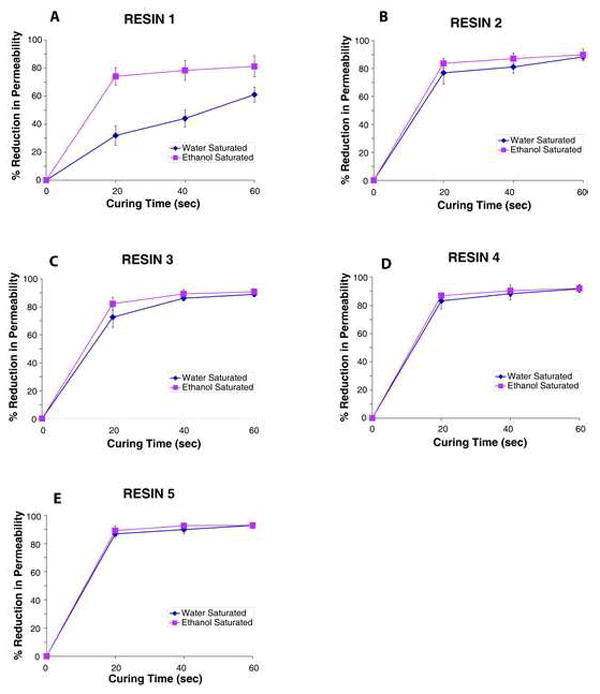

When R1, the most hydrophobic resin, was bonded to water-saturated dentin and only cured for 20 s, the dentin permeability fell to 31.9 ± 7.0% of its maximum value. Increasing the curing time to 40 or 60 s reduced the permeability 44.1 ± 6.1% and 61.1 ± 5.3%, respectively (Fig. 3A). However, when R1 was bonded to ethanol-saturated dentin and cured for 20 s, the permeability fell significantly (p<0.05) to 74.1 ± 6.2%. Increasing the curing to 40 or 60 s reduced permeability of R1 bonded ethanol-saturated dentin to 78.4 ± 7.0 and 81.2 ± 7.5%, respectively (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Plots of dentin permeability vs. degree of conversion (DC) for resins 1-5. A = resin 1; B = resin 2; C = resin 3; D = resin 4; E = resin 5.

When R2 was bonded to water-saturated dentin and cured for 20 s, the permeability fell to 76.9 ± 8.2% (Fig. 3B). Curing for 40 or 60 s produced further reductions (81.1 ± 4.5 and 88.3 ± 2.1%). When R2 was bonded to ethanol-saturated dentin, the permeability fell to about the same extent (Fig. 3B).

Bonding R3 to water-saturated dentin and curing for 20 s reduced dentin permeability by 72.6 ± 7.3%, while curing for 40 or 60 s reduced permeability to 86.2 ± 1.9 and 89.0 ± 1.3%, respectively (Fig. 3C). Bonds made to ethanol-saturated dentin were about the same when cured for the same time (Fig. 3C). R4 behaved very much like R3 in its ability to reduce dentin permeability (Fig. 3D). R5, the most hydrophilic resin, lowered dentin permeability the most (86.8, 89.9 and 92.8%) when cured for 20, 40 or 60 s (Fig. 3E) regardless of whether dentin was saturated with water or ethanol.

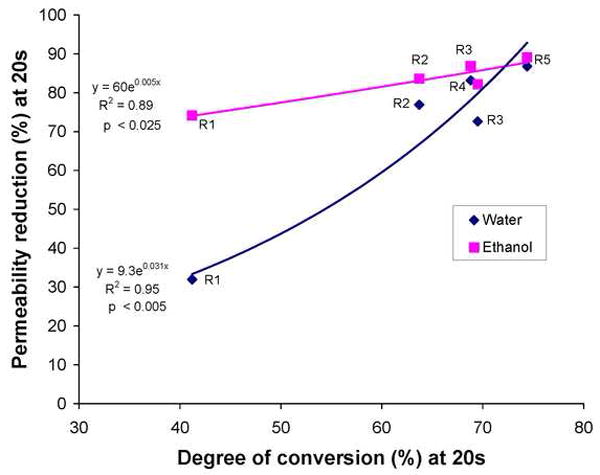

When the reductions in dentin permeability were correlated with the degree of conversion by regression analysis (Fig. 4), the relationship had a slope near zero (i.e. 0.005) when resins were bonded to ethanol-saturated dentin, but a much steeper slope (i.e. 0.031) when resins were bonded to water-saturated dentin.

Fig. 4.

The percent reduction in dentin permeability plotted against the percent conversion of resins 1-5 after 20 s of light-curing, applied to water or ethanol-saturated dentin. Although both regressions were highly significant, the slope of the regression in water-saturated dentin was much higher than when the resins were bonded to ethanol-saturated dentin. The regressions accounted for between 89 and 94% of the observed data.

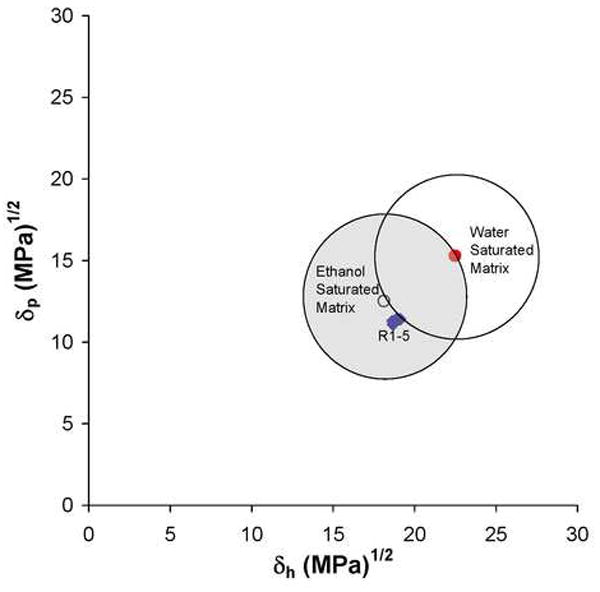

In Fig. 5, the relative miscibilities of 10% ethanol/90% R1-5 in water or ethanol-saturated dentin matrix are shown as overlapping circles when the Hoy’s solubility parameters of polar cohesive forces of the resins and substrates were plotted against their Hoy’s solubility parameters for hydrogen bonding cohesive forces. Note that all of the 10% ethanol/90% R1-5 fall near the center of the circle describing the ethanol-saturated dentin, while they barely touch the periphery of the circle centered about the water-saturated matrix. Indeed, R1 is located the furthest away from the center of the water-saturated matrix.

Fig. 5.

Plot of Hoy’s δp and δh domains (created using a 5 MPa-1 radius) around water ● vs. ethanol ○ saturated dentin matrices. Note that the 10% ethanol-solvated resins 1-5 fall just outside the water-saturated dentin matrix domain, but they fall near the center of the ethanol-saturated matrix. Thus, solubility theory would predict excellent miscibility of the experimental resins in ethanol-saturated dentin, but not for water-saturated dentin.

4. Discussion

The results of this study require rejection of the null hypotheses that the degree of conversion has a direct effect on the permeability of the experimental resins bonded to dentin, and that the permeability of the resins bonded to water-saturated dentin not different than when bonded to ethanol-saturated dentin. The results obtained with R1 skewed the regression by the low permeability reduction of R1 when applied to water-saturated dentin (Fig. 4). R1 has such a low solubility in water (data not shown), that it was unable to mix with water in the interfibrillar spaces of acid-etched dentin and was unable to penetrate into water-filled tubules. If the data obtained with R1 was excluded from the regression analysis, there was not much difference between the reductions in permeability produced by R2-5 on water or ethanol-saturated dentin. Indeed, the reductions in dentin permeability produced by R2-5 in water or ethanol-saturated dentin were not significantly different from the smear layer-covered dentin. This was in contrast to a recent report that none of the same resins used in the current study were able to reduce dentin permeability to smear layer-covered dentin values when applied to water-saturated dentin [5]. In that study, scanning electron microscopy of the resin-bonded interface revealed that neither neat R1 or R2 formed hybrid layers and resin tags to water-saturated acid-etched dentin, although they did infiltrate well into ethanol-saturated dentin [5]. There were no significant differences in the Carrilho et al. [5,6] studies between the dentin sealing ability of neat vs. 30% ethanol-solvated resins. The major differences between that study and the current one was that they light-cured for only 20 s, while we cured for 20, 40 and 60 s, and they used neat and 30% solvated resins, while the current study used 10% ethanol/90% R1-5. The Carrilho et al. [5,6] studies were done without solvent evaporation just like the current study, but their polymer films would contain more residual ethanol [27] than in the present study. The residual permeability of our resin-dentin bonds after 20 s of light-curing were not statistically different from the neat or 30% ethanol-solvated resin values of Carrilho et al. [5], except our R1 sealed water-saturated dentin much less and our R5 lowered permeability of dentin to residual values that were half those reported in the previous study, when applied to either water or ethanol-saturated dentin. Previous studies have reported wide variations in the permeability of dentin bonded with etch-and-rinse and self-etch adhesives following light-curing for 20 s with a quartz-halogen lamp delivering 600 mW/cm2. In one study, bonding acid-etched dentin with OptiBond FL (Kerr, Orange, CA, USA) reduced the permeability from 100% after acid-etching, to 23.8 ± 0.1% after bonding [22]. One-Step (Bisco, Schaumburg, IL, USA) only reduced the permeability of dentin to a residual value of 41.8 ± 0.4% [22]. Extending the curing to 60 s in that study lowered the permeability progressively until it was only 8.3 ± 1.2% and 19.9 ± 1.6% for OptiBond FL and One-Step, respectively [22]. When those same products were light-cured with LED curing units delivering 600 vs. 1200 mW/cm2 [21], they obtained similar results showing that 20 s was generally an inadequate curing time. They reported significant inverse correlations between dentin permeability and percent conversion of the adhesives.

Although R5 produced the largest reductions in dentin permeability (Table 2), polymers made from R5 absorb 23-times more water than does R1 [35]. This water sorption plasticizes the polymers making them less stiff, contributing to decreases in bond-strength over time.

The miscibility between the 10% ethanol-solvated R1-5 and the water- vs. ethanol-saturated collagen matrix can be determined by plotting their Hoy’s solubility parameters for polar cohesive forces (δp) against the solubility parameters for hydrogen-bonding cohesive forces (δh). The general rule is that miscible solutions should fall within a circle having a radius of 5 (MPa)½ around the Hoy’s solubility parameters for water vs. ethanol-saturated dentin collagen matrix [36] as shown in Fig. 4. Higher δh or δp values indicate more hydrophilicity, while lower values indicate more hydrophobicity. Note that water-saturated collagen is more hydrophilic than ethanol-saturated collagen because water has a much higher δp and δh than ethanol (Table 1). All of the 10% ethanol/90% R1-5 fall close to the center of ethanol-saturated substrate (Fig. 4) but just outside the circle of the water-saturated matrix. R1 falls further outside the water-saturated matrix than does R5. Thus, by saturating acid-etched dentin with ethanol one can infiltrate even relatively hydrophobic resins into the matrix [36,39].

Ideally, resin-dentin bonds should reduce dentin permeability to zero, the level of permeability of dentin covered with enamel or cementum. The only published report of any polymeric coatings or adhesives that can reduce dentin permeability to zero is the use of Unifil Bond (GC Corporation), a self-etching primer adhesive [3]. The degree of reduction of dentin permeability following bonding varies widely from values as low as 58.2% for One-Step (Bisco, Schaumberg, IL, USA) [22] to as high as 96.6% using All Bond 2, both etch-and-rinse adhesive [1]. Generally, the reductions in dentin permeability after bonding range between 70-85% while smear layers can reduce dentin permeability as little as 50% [2] or as much as 91-93% [5, 6, 7 and current study]. The less than perfect sealing of dentin by commercially available hydrophilic adhesives is largely due to poor sealing of dentinal tubules by resin tags [7-11]. The CLSM studies have all shown that fluorescent tracer molecules can easily diffuse around resin tags. Apparently, the resin tags can not hybridize perfectly with the surrounding water-filled interfibrillar spaces. Although solvating adhesives with ethanol or acetone promotes removal of water from interfibrillar spaces, if the ethanol/comonomer blend contains over 30% solvent, it is difficult to evaporate the excess solvent [37] from resin tags and interfibrillar spaces. If the resin tags are composed of more than 30% ethanol/70% comonomers when they are formed, we speculate that the evaporation of two-thirds of that ethanol would tend to shrink the volume of the “liquid resin tags”. It is unclear how much flow of comonomers can take place in resin tags as the solvents evaporate. Clearly, solvents can evaporate more easily from the surface of adhesive layers, but how well can they evaporate from the bottom of hybrid layers in the 5-10 s most clinicians use to evaporate solvents remains to be determined. Any residual solvent will eventually be replaced by absorbed water. That water may be responsible for leaky resin tags that prevent creation of perfect seals.

Instead of using high concentrations of ethanol in adhesives, an alternative approach is to replace all of the water in acid-etched dentin matrices with 100% ethanol, the so-called ethanol-wet bonding technique [5,6,38-40]. Theoretically, one could apply neat comonomer blends to ethanol-saturated dentin and allow them to dissolve in the ethanol in which they are very soluble, instead of undergoing phase changes in water-saturated dentin [36,40,41].

The slight but significantly greater reductions in dentin permeability obtained using ethanol-wet bonding vs. water-saturated dentin (Table 2) indicates that ethanol-saturation of acid-etched dentin can improve resin sealing. The lack of a perfect seal may be due to the osmotic effect of comonomers. That is, in acid-etched dentin that is hyperconductive for dentinal fluid, application of hypertonic comonomer mixtures (2-4 moles/L vs. 0.15 moles/L for average body fluids) to such dentin may permit sufficient outward water diffusion during the infiltration phase of bonding [6,13] to dilute the ethanol and/or contaminate the zone between the liquid comonomer “tags” and the walls of the acid-etched tubules with water, thereby preventing perfect hybridization of resin tags to the surrounding collagen fibrils and preventing the creation of perfect seals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grant DE 014911 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to DHP (PI). The authors are grateful to Michelle Barnes for secretarial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bouillaguet S, Duroux B, Ciucchi B, Sano H. Ability of adhesive systems to seal dentin surfaces: an in vitro study. J Adhes Dent. 2000;2:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grégoire G, Guignes P, Millas A. Effects of self-etching adhesives on dentin permeability in a fluid flow model. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King NM, Tay FR, Pashley DH, Hashimoto M, Ito S, Brackett WW, Garcia-Godoy F, Sunico M. Conversion of one-step to two-step self-etch adhesives for improved efficacy and extended application. Am J Dent. 2005;18:126–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yiu CK, Hiraishi N, Chersoni S, Breschi L, Ferrari M, Prati C, King NM, Pashley DH, Tay FR. Single-bottle adhesives behave as permeable membranes after polymerisation. II. Differential permeability reduction with an oxalate desensitiser. J Dent. 2006;34:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrilho MR, Tay FR, Sword J, Donnelly AM, Agee KA, Nishitani Y, Sadek FT, Carvalho RM, Pashley DH. Dentine sealing provided by smear layer/smear plugs vs. adhesive resins/resin tags. Eur J Oral Sci. 2007;115:321–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrilho MR, Tay FR, Donnelly AM, Agee KA, Carvalho RM, Hosaka K, Reis A, Loguercio AD, Pashley DH. Membrane permeability properties of dental adhesive films. J Biomed Mater Res Part B (Appl Biomater) 2008 doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30968. available online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths BM, Naasan M, Sherriff M, Watson TF. Variable polymerization shrinkage and the interfacial micropermeability of a dentine bonding system. J Adhes Dent. 1999;1:119–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths BM, Watson TF, Sherriff M. The influence of dentine bonding systems and their handling characteristics on the morphology and micropermeability of the dentine adhesive interface. J Dent. 1999;27:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pioch T, Staehle HJ, Duschner H, Garcia-Godoy F. Nanoleakage at the composite-dentin interface. A review. Am J Dent. 2001;14:252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Alpino PH, Pereira JC, Svizero NR, Rueggeberg FA, Carvalho RM, Pashley DH. A new technique for assessing hybrid layer interfacial micromorphology and integrity: Two-photon laser microscopy. J Adhes Dent. 2006;8:279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosales-Leal JI, Torre-Morena FJ, Bravo M. Effect of pulp pressure on the micropermeability and sealing ability of etch & rinse and self-etching adhesives. Oper Dent. 2007;32:242–250. doi: 10.2341/06-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauro S, Pashley DH, Montanari M, Chersoni S, Carvalho RM, Toledano M, Osorio R, Tay FR, Prati Ci. Effect of simulated pulpal pressure on dentin permeability and adhesion of self-etch adhesives. Dent Mater. 2007;23:705–713. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashimoto M, Tay FR, Ito S, Sano H, Kaga M, Pashley DH. Diffusion-induced water movement within resin-dentin bonds during bonding. J Biomed Mater Res Part B. 2006;79B:453–458. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobson T, Söderholm KJ. Some effects of water on dentin bonding. Dent Mater. 1995;11:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(95)80048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Water treeing - a potential mechanism for degradation of dentin adhesives. Am J Dent. 2003;16:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Have dentin adhesives become too hydrophilic? J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:726–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chersoni S, Suppa P, Grandini S, Goracci C, Monticelli F, Yiu C, Huang C, Prati C, Breschi L, Ferrari M, Pashley DH, Tay FR. In vivo and in vitro permeability of one-step, self-etch adhesives. J Dent Res. 2004;83:459–464. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tay FR, Pashley DH, Suh BI, Carvalho RM, Miller MB. Single-step, self-etch adhesives behave as permeable membranes after polymerization. I. Bond strength and morphologic evidence. Am J Dent. 2004;17:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tay FR, Frankenberger R, Krejci I, Bouillaguet S, Pashley DH, Carvalho RM, Lai CNS. Single-bottle adhesives behave as permeable membranes after polymerization. I. In vivo evidence. J Dent. 2004;32:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tay FR, Pashley DH, Suh BI, Hiriashi N, Yiu CKY. Water treeing in simplified dentin adhesives - Deja Vu? Buonocore Memorial Lecture. Oper Dent. 2005;30:561–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breschi L, Cadenaro M, Antoniolli F, Sauro S, Biasotto M, Prati C, Tay FR, Di Lenarda R. Polymerization kinetics of dental adhesives cured with LED: correlation between extent of conversion and permeability. Dent Mater. 2007;23:1006–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cadenaro M, Antoniolli F, Sauro S, Tay FR, Di Lenarda R, Contardo L, Prati C, Biasotto M, Breschi L. Degree of conversion and permeability of dental adhesives. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Landuyt KL, Snauwaert J, DeMunck J, Coutinho E, Poitevin A, Yoshida Y, Suzuki K, Lambrechts P, Van Meerbeek B. Origin of interfacial droplets in one-step adhesives. J Dent Res. 2007;86:739–744. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito S, Tay FR, Hashimoto M, Yoshiyama M, Saito T, Brackett WW, Waller JL, Pashley DH. Effects of multiple coatings of two all-in-one adhesives on dentin bonding. J Adhes Dent. 2005;7:133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashimoto M, Tay FR, Ito S, Sano H, Kaga M, Pashley DH. Permeability of adhesive resin films. J Biomed Mater Res Part B: Appl Biomater. 2005;74B:699–705. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishitani Y, Yoshiyama M, Donnelly AM, Agee KA, Sword J, Tay FR, Pashley DH. Effects of resin hydrophilicity on dentin bond strength. J Dent Res. 2006;85:1016–1021. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cadenaro M, Breschi L, Rueggeberg FA, Suchko M, Agee KA, Di Lenarda R, Tay FR, Pashley DH. Effects of residual ethanol on the rate and percent conversion of five experimental resins. Dent Mater. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.11.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pashley DH, Depew DD. Effects of the smear layer, Copalite, and oxalate on microleakage. Oper Dent. 1986;11:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pashley DH, Carvalho RM, Pereira JC, Villaneuva R, Tay FR. The use of oxalate to reduce dentin permeability under adhesive restorations. Am J Dent. 2001;14:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rueggeberg FA, Hashinger DT, Fairhurst CW. Calibration of FTIR conversion analysis of contemporary dental resin composites. Dent Mater. 1990;6:241–9. doi: 10.1016/S0109-5641(05)80005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruyter IE, Svendsen SA. Remaining methacrylate groups in composite restorative materials. Acta Odontol Scand. 1978;36:75–82. doi: 10.3109/00016357809027569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rueggeberg FA, Craig RG. Correlation of parameters used to estimate monomer conversion in a light-cured composite. J Dent Res. 1988;67:932–7. doi: 10.1177/00220345880670060801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eliades GC, Vougiouklakis GJ, Caputo AA. Degree of double bond conversion in light-cured composites. Dent Mater. 1987;3:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(87)80055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito S, Hashimoto M, Wadgaonkar B, Svizero N, Carvalho RM, Yiu C, Rueggeberg FA, Foulger S, Saito T, Nishitani Y, Yoshiyama M, Tay FR, Pashley DH. Effects of resin hydrophilicity on water sorption and changes in modulus of elasticity. Biomater. 2005;26(33):6449–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pashley DH, Tay FR, Carvalho RM, Rueggeberg FA, Agee KA, Carrilho M, Donnelly A, Garcia-Godoy F. From dry bonding to wet bonding to ethanol-wet bonding: A review of the interactions between dentin matrix and solvated resins using a macromodel of the hybrid layer. Am J Dent. 2007;20:7–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dickens SH, Cho BH. Interpretation of bond failures through conversion and residual solvent measurements and Weibull analysis of flexural and microtensile bond strengths of bonding agents. Dent Mater. 2005;21:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadek FT, Pashley DH, Nishitani Y, Carrilho MR, Donnelly A, Ferrari M, Tay FR. Application of hydrophobic resin adhesive to acid-etched dentine with an alternative wet bonding technique. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2008;84A:19–20. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tay FR, Pashley DH, Kapur RR, Carrilho MRO, Hur YB, Garrett LV, Tay KCY. Bonding BisGMA to dentin – a proof of concept. J Dent Res. 2007;96:1034–1039. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Landuyt KL, DeMunck J, Snauwaert J, Coutinho E, Poitevin A, Yoshida Y, Inoue S, Peumans M, Suzuki K, Lambrechts P, Van Meerbeek B. Monomer-solvent phase separation in one-step self-etch adhesives. J Dent Res. 2005;84:183–188. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spencer P, Wang Y. Adhesive phase separation at the dentin interface under wet bonding conditions. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:447–456. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]