Abstract

The migratory movements of seabirds (especially smaller species) remain poorly understood, despite their role as harvesters of marine ecosystems on a global scale and their potential as indicators of ocean health. Here we report a successful attempt, using miniature archival light loggers (geolocators), to elucidate the migratory behaviour of the Manx shearwater Puffinus puffinus, a small (400 g) Northern Hemisphere breeding procellariform that undertakes a trans-equatorial, trans-Atlantic migration. We provide details of over-wintering areas, of previously unobserved marine stopover behaviour, and the long-distance movements of females during their pre-laying exodus. Using salt-water immersion data from a subset of loggers, we introduce a method of behaviour classification based on Bayesian machine learning techniques. We used both supervised and unsupervised machine learning to classify each bird's daily activity based on simple properties of the immersion data. We show that robust activity states emerge, characteristic of summer feeding, winter feeding and active migration. These can be used to classify probable behaviour throughout the annual cycle, highlighting the likely functional significance of stopovers as refuelling stages.

Keywords: geolocator tracking technology, tracking pelagic seabirds, Bayesian machine learning, migration, Manx shearwater, spatial ecology

1. Introduction

The long-distance migratory movements and winter habitats of pelagic seabirds remain poorly understood, despite these animals' role as harvesters of marine ecosystems on a global scale and their potential as indicators of ocean health (Shaffer et al. 2006). Traditional studies based on ringing recoveries or ocean sightings have proved valuable for identifying very general movement patterns, but fail to characterize any behavioural detail or discriminate important localities at sea, which may be critical both for understanding the dynamics of oceanic migration processes, and for identifying Important Bird Areas and candidate Marine Protection Area networks for conservation. New telemetry systems continue to revolutionize the study of elusive pelagic lifestyles, so that the foraging ranges and migratory behaviour of larger, predominantly southern species such as albatrosses and larger petrels are becoming much better understood (Weimerskirch et al. 2002; Phillips et al. 2006, 2008). Recently (Shaffer et al. 2006; Gonzales-Solis et al. 2007; Felicisimo et al. 2008), miniature geolocation technology has been used to track sub-1000 g seabirds on trans-equatorial oceanic migrations. In this study, we used geolocation technology, combined with a novel application of analytical techniques adapted from machine learning, to elucidate the details of large-scale pelagic movements in a 400 g Northern Hemisphere breeding procellariform, the Manx shearwater Puffinus puffinus, both during breeding and during its trans-equatorial, trans-Atlantic annual migration.

The majority of the world population of Manx shearwaters breed in Britain and Ireland (Hamer 2003), combining spatially restricted colonial breeding with a highly pelagic lifestyle. The species is therefore of particular interest to the study of migration ecology, and potentially to understanding the impacts of changing ocean health on a global integrator of marine resources. Much of the breeding biology is known from the studies on two Welsh islands, Skokholm and Skomer (e.g. Brooke 1990), which hold in excess of 150 000 breeding pairs (Smith et al. 2001), perhaps 35–40 per cent of the total breeding population (Hamer 2003). Recently, miniature GPS devices have enabled us to track breeding birds on their feeding trips from the colony (Guilford et al. 2008) but, as with most pelagic seabirds, very little detail is known about their behaviour or habitat requirements during the non-breeding season (September to March). Ringing recoveries indicate that Manx shearwaters spend the northern winter off the coast of South America, with most recoveries coming from Brazil (Perrins & Brooke 1976; Thompson 2002; Hamer 2003), but such data do not provide accurate wintering destinations and provide almost no behavioural detail. Furthermore, females undertake a pre-laying exodus (Brooke 1990) during which they build their large egg (15% of body weight), a critically important behavioural characteristic of procellariforms that remains poorly understood in this or any species.

In addition to geolocation data, a subset (7 out of 12) of our devices collected salt-water immersion data, logging the proportion of every 10 min period that the bird was on or under the water as opposed to in the air. We used a Bayesian analysis adapted from machine learning techniques to identify distinct behavioural categories inherent in the patterns within the immersion records, and used this to shed light on the birds' behaviour at different stages of the migratory cycle: during summer feeding, winter feeding, migration and egg formation. In particular, we identify what appear to be migratory stopover periods that we hypothesize may function in the same way as stopovers in terrestrial migrants for refuelling. We believe that this and similar machine learning techniques may have considerable usage in helping to extract more information from extant and future animal tracking datasets.

2. Material and methods

(a) Geolocators

We fitted twelve 2.5 g archival light logging geolocators to elliptically shaped plastic rings to the legs of both members of six established breeding pairs on Skomer Island, Wales (coordinates 51°44′ N, 5°19′ W). The five Mk6 and seven Mk9 devices, designed and manufactured by the British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, were ground-truthed before and after deployment, deployed in late August 2006, and retrieved after egg laying in the following breeding season. All 12 birds returned to breed, and data were retrieved successfully from all 12 devices.

(b) Analysis of location data

Data were analysed initially in MultiTrace software (Jensen Software Systems), with the correction factor for day/night movement set to 0.5, an elevation angle of −5.5° and a simple correction for fast east/west movement (see MT Geolocation manual available at: http://www.jensen-software.com/downloads.html July 2008 for more details), a choice aided by reference to the known ground-truthed position at the colony. Day length is used to provide an estimate of latitude, while the timing of recorded midday or midnight is used to provide an estimate of longitude. The quality of our light curves was very good, so it is likely that error is similar to that found in previous studies even at higher latitudes (see Phillips et al. 2004 and Shaffer et al. 2005 for discussion of geolocation accuracy). Because day length approaches uniformity across the globe at the equinoxes, erroneous location estimates are often seen around these periods and these were excluded. Points were also regarded as erroneous if they involved more than 1600 km position change in 1 day, lay in a line along the equator or were affected by obvious interference in the light curve around sunrise and sunset. Eighty per cent occupancy kernels were used to identify individual over-wintering areas, and a 500 km boundary from the colony was used to define the breeding area, for the purposes of calculating migration, breeding or over-wintering statistics. Since longitude is more accurately estimated than latitude (e.g. Wilson et al. 1992; Hill 1994), especially around the equinoxes, we used change in longitude to identify stopover periods during migration. A stopover was defined as a period in which there was less than a 0.8° change in longitude in half a day smoothed over 3 days and contiguous for at least 2.5 days.

(c) A Bayesian approach to inferring behaviour classes from immersion data

All seven Mk9 devices returned with complete logs of salt-water immersion. Each device registered whether or not it was submerged in salt-water every 3 s, and recorded the number of such immersions in each 10 min period throughout every day as a value from 0 (in air over entire period) to 200 (immersed over entire period). Figure 1 illustrates how immersion data are distributed over a typical 24 hour period. These data can be used simply to determine whether a bird is flying, or is on or under the water. However, since the pattern of immersion versus flying events across a day or night is likely to reflect a bird's behaviour on a larger scale (e.g. foraging versus long- or short-distance movements), we attempted to determine whether consistent patterns existed in the data. Our approach was to develop a method of unsupervised probabilistic machine classification, which we then cross-verified with a supervised classification based on prior knowledge of likely behavioural states (further explanation is given in the electronic supplementary material). First, we determined a set of candidate dimensions for each 24 hour period, such as number of wet events (defined as crossings over a threshold value of 100; see figure 1), number of dry events or the mean time of all wet events during the day or night (time over or under threshold). We chose three dimensions that were well-distributed over their range to allow the classifier to subdivide the space most effectively into separate classes. We made no assumption about the order of the days, the particular birds or the meaning of the behaviour. As the best dimensions for the unsupervised classifier, we chose: (i) mean length of dry events under the threshold in daytime, (ii) total wet time as a proportion of daytime, and (iii) total wet time as a proportion of night time. We used a Gaussian mixture model for unsupervised classification with a number of components determined from the data and inferred using the variational Bayes learning approach (Attias 2000; Roberts & Penny 2002; Roberts et al. 2004; Bishop 2006). The unsupervised classifier automatically clusters data according to its self-similarity into a number of putative groupings and, for each 24 hour section, gives a probability of membership to one of a set of putative classes. This classifier (which starts with 20 potential classes, and pares down to the most parsimonious subset) produced three major classes and several minor classes (98% of days were classified into three main classes), and the classifications were similar across all birds.

Figure 1.

Example of salt-water immersion data for a 24 hour period for bird FR53237 on 28 July 2006. Dark (night time) periods are shown shaded grey and a threshold at 100 units is indicated by a grey line. The plot shows how the bird changes frequently between sitting/diving and flying/on land, with a period of flight in the middle of the day (immersion value 0), and approximately 100 min period from nightfall sitting on the water (immersion value 200), presumably rafting, before coming ashore (immersion value 0).

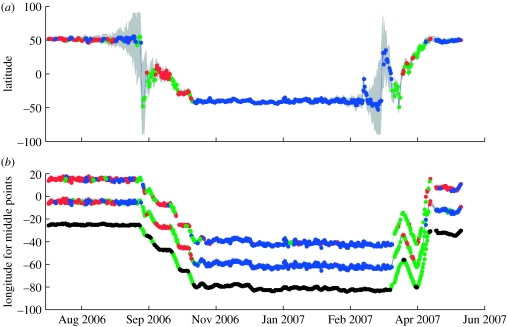

Next, we used a supervised classification (Fisher 1936; Martinez & Martinez 2008) to provide some verification of our unsupervised classification (figure 2). To train the classifier, we divided broad sections of the data into migration, summer feeding and over-wintering for an arbitrarily chosen bird, using a combination of dates, known activity at the colony and location as revealed by the light data. The same selection of candidate dimensions within the immersion data used for the unsupervised classifier was again examined using the supervised classifier. Three dimensions were chosen that best differentiated between classes after direct comparison of probability density functions of class membership for the training data. We used odd and even alternative data points as training groups to provide classification for the training data within the initially classified periods chosen by the expert, as well as at times which had been initially unclassified. This method allows for cross-validation to calculate the probability of correct classification (which was 0.79; Martinez & Martinez 2008). Supervised classification produces a probability of membership for each class. Each data point (24 hour period) is assigned to the class it has the highest probability of belonging to. A lower threshold was also set where the probability of membership of any class was so low that the point remained unclassified. All days from all birds were classified using these same training data from the arbitrarily chosen bird. The classification of activity was remarkably consistent across all birds and compared well in all cases with the output of the unsupervised classifier. We made a comparison by matching the class assignments from the two classifiers and, for each bird, calculating the percentage of points that were consistently classified. There was a mean consistent classification of 67 per cent (s.d. 5%) for the seven birds.

Figure 2.

(a) Unsupervised classification from immersion data for FP52700 overlaid on latitude. The likely relative error in latitude is shown in grey, and is calculated by making perturbations around the measured value. With a constant precision in measurement, error in latitude near the equinox is higher because the day length is similar for all latitudes (i.e. perturbations have to be greater to produce a similar effect than at other times of year). (b) Supervised classification from immersion data (upper trace) and unsupervised classification from immersion data (middle trace) overlaid on longitude are shown for the same bird as in (a). The lower trace indicates periods of migratory movement defined entirely from longitudinal displacement (the longitude positions were smoothed with a boxcar filter of length 3 days and a position classified as migration if it differed from the previous one by more than 0.8 degrees). The upper and lower traces have been offset by ±20° for clarity. The general agreement between the classifiers is shown, as are several stopovers on the outward- and inward-bound migrations that are independently classified as feeding from the immersion data. Blue dots, winter feeding; green dots, migration; red dots, summer feeding; black dots, feeding (either); grey line, position; grey area, position error.

3. Results

(a) Broad movement patterns

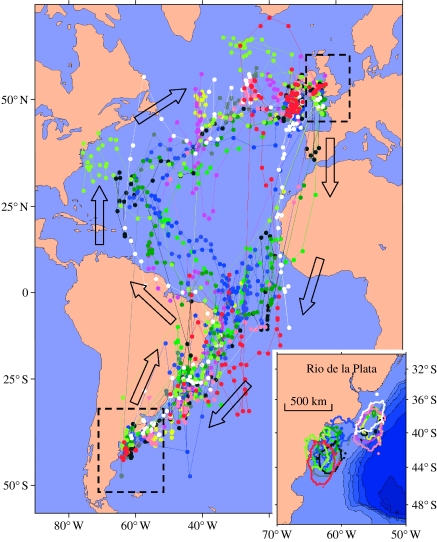

Figure 3 summarizes the broad pattern of migration for all 12 birds. It is important to recognize that, while clearly erroneous points based on putative movement distances have been removed, points on land have not because of the biasing effect that this procedure would have on overall distribution centres. This is because there is no a priori reason to expect land-based points to be less accurate than those over the ocean. Nevertheless, known natural history of this species makes it extremely unlikely that such points represent genuine excursions onto land. Inferential gaps still exist because of poor resolution around the autumn equinox in particular, but the data indicate a southwards migration down the west coast of Africa and across to the Brazilian coast via approximately the shortest route, then south or southwest to over-wintering quarters on the Patagonian Shelf off Argentina centred on latitude 40° south. Fifty per cent occupancy contours at the over-wintering area suggest that individual over-wintering cores are quite similar for all 12 birds, although with the possibility that there may be two distinct destinations. All birds overwintered close to the Argentinean coast. The return northwards tended to follow a westwardly curved route through the eastern Caribbean, even as far as the eastern seaboard of the US and back through the north Atlantic. A single (female) bird flew a more direct return migration.

Figure 3.

Positions of 12 shearwaters tracked with geolocators. Each bird is represented by a different colour. Coloured lines serve to connect the positions in series providing approximate trajectories. However, where erroneous locations have been excluded, lines may sometimes connect neighbouring positions that are many days apart and hence are not indicative of actual routes travelled (e.g. over land). For clarity around the breeding colony and the main over-wintering area (inside the dashed boxes) where there is a high density of points, plots are of mean positions over two-week periods. The inset shows the 50% occupancy contours within the southern dashed box around the over-wintering area for all daily positions within that box, using the same colour scheme as the tracks. Bathymetry contours at 1000 m intervals indicate the edge of the Patagonian Shelf.

Beyond the broad pattern, however, several important details emerge (see table 1 for values and statistics). Males and females departed on autumn migration (defined as date last recorded within 500 km of the colony) at about the same time, and migration to the 80 per cent over-wintering kernel did not cover significantly different periods (although a larger sample might reveal differences). The duration of the return (northerly) migration, however, was significantly longer in males than females. This was the case even though males tended to arrive on the colony earlier than females (although not significantly so in our sample). The fastest sustained migratory travel was recorded for a male during his southerly migration when he covered, within the uncertain accuracy limits of the devices, a straight-line distance of approximately 7750 km in 6.5 days, a speed of 1192 km a day. In fact, using the immersion data, we were able to calculate that this bird achieved this journey in 139 hours airtime, hence an average surface flight speed of 55 km h−1.

Table 1.

Summary of migration statistics.

| males (n=6) | females (n=6) | Wilcoxon rank-sum test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| southerly migration departure date, mean (and range) | 20 Sep (07 Sep–23 Sep) | 21 Sep (13 Sep–23 Sep) | p=1.000 |

| southerly migration duration, mean (and range) | 25.8 days (14–44 days) | 35.0 days (26–42 days) | p=0.092 |

| time at over-wintering core (80%), mean (and range) | 139.7 days (125–150 days) | 149.3 days (138–156 days) | p=0.058 |

| northerly migration departure date, mean (and range) | 3 Mar (08 Feb–30 Mar) | 23 Mar (01 Mar–07 Apr) | p=0.065 |

| northerly migration duration, mean (and range) | 40.2 days (30–58 days) | 27.6 days (22–35 days) | p=0.019 |

| arrival near colony, mean (and range) | 13 Apr (06 Apr–29 Apr) | 20 Apr (23 Mar–06 May) | p=0.229 |

| stopover days southwards, mean (and range) | 8.1 days (0–30.5 days) | 13.9 days (0–23 days) | p=0.309 |

| stopover days northwards, mean (and range) | 13.3 days (0–23 days) | 7.4 days (0–18.5 days) | p=0.143 |

| number of stopovers per bird, mean (and range) | 3.2 (1–6) | 3.3 (2–5) | p=0.871 |

| duration of individual stopovers, mean (and range) | 6.7 days (2.5–13.5 days) | 6.4 days (2.5–15.5 days) | p=0.516 |

| total number of stopover days, mean (and range) | 21.3 days (4.5–41.5 days) | 21.3 days (14.5–32 days) | p=0.872 |

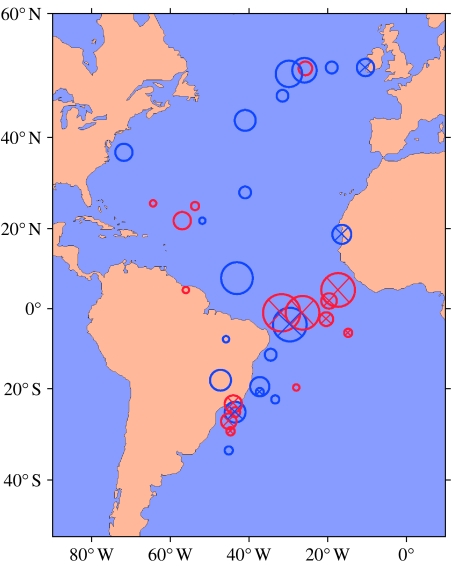

(b) Stopovers

Birds did not migrate continuously. Instead, they often split their journeys with one or more periods in which there was little onward progress. Such periods are poorly resolved spatially during the early part of the outward migration close to the autumn equinox; but during the latter part of outward migration and during return migration, birds appeared to spend from a few days to as long as two weeks in activity apparently unrelated to migratory travel (figure 4). If we define these periods as stopovers using minimal change in longitude, we see that all birds made stopovers, that they are made by both males and females, and that they are made with approximately equal frequency and duration on both outward and return migrations (table 1). We hypothesize that these are marine stopovers functionally equivalent to the stopovers characteristic of many terrestrially migrating birds replenishing their reserves (see Newton 2008 for a recent review).

Figure 4.

Stopovers, sized in proportion to the length of the stop, are shown at mean location of positions. Blue, male; red, female (small circles, duration 5 days; big circles, duration 10 days). Outward-bound stops from colony towards winter feeding ground are indicated with a cross. Locations apparently over land almost certainly do not indicate that birds were stopping inland, but serve to emphasize that position estimates may be subject to considerable error.

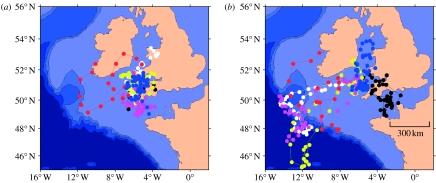

(c) Pre-laying exodus

Using light and/or immersion data, we were able to identify the egg-formation period by examining the male and female simultaneous presence on land at the colony at the start of the breeding season followed by a protracted period of female absence. For some pairs, approximate or even exact egg-laying dates from burrow inspections were used as verification (pre-laying exodus: mean start date=3 May; mean end date=23 May; mean duration=20 days). Figure 5 shows the approximate tracks and positions of the six breeding pairs with sexes plotted separately.

Figure 5.

Positions averaged over 2-day periods for six shearwater pairs, (a) male and (b) female, during the period immediately after the return from winter migration and before the egg is laid (pre-laying exodus). Colours are consistent within pairs. Most male birds remain close to the colony while the females move further away, with four moving towards the shelf edge southwest of Ireland. All females laid an egg immediately after returning to the colony after these trips, except FR88595, which stayed in the Irish Sea—shown in blue. Bathymetry contours at 1000 m intervals indicate the edge of the continental shelf.

(d) Behaviour classification using immersion data

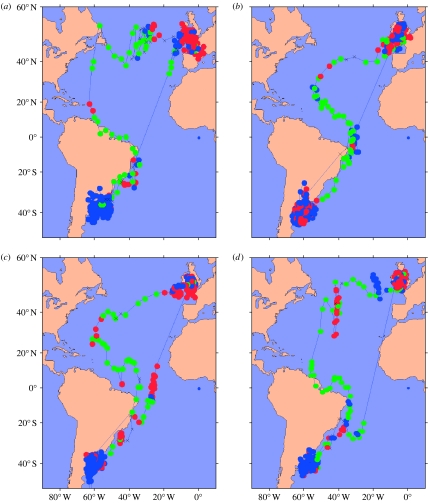

Three dominant classes emerge robustly from the unsupervised classification of the salt-water immersion data. Assigning these three classes to data on plots of latitude or longitude indicates that they generally correspond to definable periods of the shearwater's year (figure 2). One class is most often associated with major changes in position (green dots, figure 2), and the other two classes are associated predominantly with activity during the breeding season (red dots) and during the over-wintering period (blue dots).

Plotting these states on a spatial map provides a clearer picture of the shearwater's activity during the migratory cycle. Figure 6 shows the tracks of four birds, two male and two female, with successive points joined by lines (noting that there may be periods of missing data between two successive points, particularly around the equinoxes). Colours refer to membership of the most probable class identified by the unsupervised classification. Since this classification shows a strong (67%) overlap with the supervised classification, we may use the terms summer feeding (red dots, figure 6), winter feeding (blue dots) and migration (green dots) to label the classes.

Figure 6.

The tracks of four birds, two male and two female, with successive points joined by lines (noting that there may be periods of missing data between two successive points, particularly around the equinoxes). The points are coloured red, green and blue, with respect to their posterior probability of classification into one of three classes using the supervised classifier. Red, summer feeding; blue, winter feeding; green, migration. (a) FR53237 male, (b) FB22795 female, (c) FP52700 female, (d) FC83751 male.

For the pre-laying exodus period immersion data, classification was possible for four out of the six female birds. For all the classifiable days (147) using both classifiers, 56 per cent of days were classified as winter feeding and 32 per cent as summer feeding, with the remainder classified as migration (although here the dataset is small and the congruence between the two classifiers is less good).

4. Discussion

In contrast to two previously studied trans-equatorial migrant shearwaters, Cory's shearwater Calonectris diomedea and sooty shearwater Puffinus griseus, which exploit several different over-wintering areas even when birds are from the same colony (Shaffer et al. 2006; Gonzales-Solis et al. 2007), breeding Manx shearwaters appear to depend on a single, remarkably restricted area (with the caveat that this and other inferences are from data gathered on 12 birds). This area is close to the Argentinean coast south of the Río de la Plata, further south than expected from ringing recoveries (Thompson 2002), but on an area of the Patagonian Shelf where mixing ocean currents are known to produce rich fisheries heavily exploited both by other pelagic animals and by humans (e.g. Phillips et al. 2005).

The broad pattern of migration to and from this over-wintering area is consistent with the earlier models based on indirect data, primarily ringing recoveries (Brooke 1990). It suggests a considerable degree of control by oceanic winds, as has been argued for this and other species by Felicisimo et al. (2008). The distinctly different outward and return routes north of the equator suggest reliance on the trade winds of the north Atlantic gyre. As noted above, the fastest sustained migratory travel was recorded as approximately 55 km h−1 for a male in flight for a continuous 139 hours. This is the maximum range speed estimated for this species by Pennycuick (1969), but it is considerably faster than the 40 km h−1 mean airspeed estimate measured during foraging excursions of Manx shearwaters using GPS (Guilford et al. 2008), which implies that such performance is likely to have been achieved with considerable use of favourable wind conditions. Sooty shearwaters (Shaffer et al. 2006) can achieve similar speeds during rapid migration, and Manx shearwaters were often recorded by GPS moving at 55 km h−1 or faster during foraging excursions from their breeding colony (Guilford et al. 2008), presumably by exploiting wind assistance. Nevertheless, the southern portion of the return migration does not appear to be driven primarily by wind dynamics, which would predict an easterly movement from the over-wintering area initially to exploit the gyre in the south Atlantic (e.g. Felicisimo et al. 2008). An alternative explanation is that returning migrants continue to exploit fishing opportunities off the coast of Brazil as they start their return, which might instead allow a reduction in the cost of migratory transport by requiring lighter on-board fat reserves.

It is clear, however, that migration usually takes much longer than could in principle be achieved in sustained travel, particularly for males. Closer inspection of the data reveals that birds do not normally make their journey in a single flight, but have one or more periods in which there is little onward progress for up to two weeks at a time. We have labelled these periods as stopovers, which are equally common in males and females, and hypothesized that they may serve the same refuelling function as the traditional staging areas of terrestrial migrants (e.g. Newton 2008). Similar staging areas have been noted for black-browed albatrosses (Phillips et al. 2005), but have not so far been seen in the most comparable species whose trans-equatorial migrations have been similarly tracked, the Cory's (Gonzales-Solis et al. 2007) and sooty (Shaffer et al. 2006) shearwaters, for reasons unknown. A larger dataset will be required to determine whether there is any systematic relationship between the timing and position of stopovers and environmental variables. Nevertheless, our initial analyses indicate that, while strong headwinds associated with passing weather systems sometimes coincide with stopping periods, on other occasions this is not the case. Hence, while there may be adverse weather explanations for some stopovers, others cannot be accounted for in this way, and some clearly outlive the longevity of weather systems. Stopover sites are recognized as important areas for terrestrial migrants, but at sea their distance from land and probably mobile nature may well have allowed them to go largely unrecognized for marine migrants.

Apart from a longer return migration in males than females, there are no obvious differences in movement patterns between the sexes (although it is clear that members of a pair do not synchronize migration). The major exception to this involves the pre-laying exodus from the colony when we show that for a majority of females there is a distinct southwest to westerly displacement (near the continental shelf edge) from the normal breeding-season foraging destinations (see Guilford et al. 2008). Either these destinations must provide females with special resources for egg formation, or they are simply rich foraging areas that are out of range for males on nest-guarding duty and all breeding birds while tending eggs and chicks. One of the two females not showing this pattern (FR88595) failed to lay an egg in 2007. Female black-browed albatrosses also move further from their colony than do males during their pre-laying exodus (Phillips et al. 2005).

The three dominant classes of behaviour recognized by the unsupervised classification of the immersion data overlap well with those recognized by the supervised classification trained on expert selected periods of migration, over-wintering and breeding-period foraging trips. This allows some confidence in using the unsupervised classes to identify probable activity types at other stages of the migratory cycle without expert scrutiny or dependence on location data required by the expert. Our analysis, which may have general applicability to similar datasets and which allows the extraction of information not immediately evident to researchers using informal human pattern recognition, highlights two striking features.

First, activity at the two core destinations, the Irish Sea during summer breeding and the Patagonian Shelf during over-wintering, is distinct. A priori we had no expectation of this. There is perhaps an obvious hypothesis: that summer foraging involves periods of movement to and from the colony, while during winter birds have only to look after themselves and may thus remain more sedentary. Scrutiny of the stopover periods in particular, when there is no return to the colony, indicates a proportion of activity classed most similar to summer feeding, which argues against the hypothesis that one particular activity such as commuting determines the classification. An alternative explanation is that different search or foraging styles may be required in different areas where prey type, availability or local distributions themselves differ (e.g. Weimerskirsch et al. 1994). Differences in wing loading between winter and summer are another possibility, since shearwaters are thought to moult gradually over the winter. Periods of active migration, on the other hand, are distinctively different again, and are clearly associated with the long-distance migratory movements between the two core destinations. This can be seen from the spatial pattern of days classed as migration, and there is a strong congruence with days where there are large changes in longitude (e.g. figure 5). But, again, our unsupervised classification does not require spatial information, so it can in principle be used to identify periods of migration where spatial data are unavailable.

Second, stopover periods, which are defined by spatial criteria, commonly contain activity patterns more typical of summer or winter feeding than of active migration (58% of stopover days overall show winter or summer foraging type characteristics in equal proportions). This supports the hypothesis that stopovers may indeed be refuelling stops integral to the shearwater's migration tactics. Such behaviour, which has critical implications for the protection of important resource areas at sea, has so far gone little noted in seabirds.

This paper represents a first attempt to use analytical techniques originally developed within machine learning to identify behaviour remotely using a combination of immersion and spatio-temporal data from miniature geolocation technology. Our fully Bayesian approach is new because we have initially classified behaviour states from salt-water immersion data, independently of location (the closest related work we know of is Roberts et al. 2004). This has the advantage of later allowing cross-validation with the location data. The aim is not to produce a comprehensive interpretation of the data or of Manx shearwater migration: more refined techniques and larger datasets may be required for this. The aim is to show how such a cross-disciplinary approach may offer a potentially powerful and relatively uninvasive way to study the more elusive life histories of smaller, highly pelagic seabirds, many of which are of vulnerable status. Our approach may be extendable to many other complex datasets where informal analysis cannot easily tease out important hidden patterns.

Acknowledgments

We thank Louise Maurice, Christine Nicol, Tom Evans and the staff and volunteers of Skomer Island for their field assistance. The Wildlife Trust for South and West Wales, and the Countryside Council for Wales, provided logistical or financial support.

Oxford University Local Ethical Review procedures were followed throughout this project, which does not fall under A(SP)A, conformed to ASAB guidelines for ethical research and was conducted with appropriate BTO ringing licences and a CCW permit.

Supplementary Material

Both the unsupervised and supervised methods presented in the paper are underpinned by Gaussian mixture models, and the detailed logic behind our methods is explained here.

References

- Attias H. A variational Bayesian framework for graphical models. In: Leen T., et al., editors. Proceedings of NIPS 12. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C. 2006 Pattern recognition and machine learning New York, NY: Springer. (doi:10.1117/1.2819119)

- Brooke M. T. & A. D. Poyser; London, UK: 1990. The Manx shearwater. [Google Scholar]

- Felicisimo A.M., Munoz J., Gonzalez-Solis J. Ocean surface winds drive dynamics of transoceanic aerial movements. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002928. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R.A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann. Eugen. 1936;7:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Solis J., Croxall J.P., Oro D., Ruiz X. Transequatorial migration and mixing in the wintering areas of a pelagic seabird. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007;5:297–301. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[297:TMAMIT]2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Guilford T.C., Meade J., Freeman R., Biro D., Evans T., Bonadonna F., Boyle D., Roberts S., Perrins C.M. GPS tracking of the foraging movements of Manx shearwaters Puffinus puffinus breeding on Skomer Island, Wales. Ibis. 2008;150:462–473. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2008.00805.x [Google Scholar]

- Hamer K.C. Puffinus puffinus Manx shearwater. BWP Update. 2003;5:203–211. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.1997.00118.x [Google Scholar]

- Hill R.D. Theory of geolocation by light levels. In: Le Boeuf B.J., Laws R.M., editors. Elephant seals: population ecology, behaviour and physiology. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1994. pp. 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez W.L., Martinez A.L. 2nd edn. Chapman and Hall; London, UK: 2008. Computational statistics handbook with Matlab. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, I. 2008 The migration ecology of birds London, UK: Academic Press. (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.010)

- Pennycuick C.J. The mechanics of bird migration. Ibis. 1969;111:525–556. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1969.tb02566.x [Google Scholar]

- Perrins C.M., Brooke M.de L. Manx shearwaters in the Bay of Biscay. Bird Study. 1976;23:295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R.A., Silk J.R.D., Croxall J.P., Afanasyev V., Briggs D.R. Accuracy of geolocation estimates for flying seabirds. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004;266:265–272. doi:10.3354/meps266265 [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R.A., Silk J.R.D., Croxall J.P., Afanasyev V., Bennett V.J. Summer distribution and migration of nonbreeding albatrosses: individual consistencies and implications for conservation. Ecology. 2005;86:2386–2396. doi:10.1890/04-1885 [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R.A., Silk J.R.D., Croxall J.P., Afanasyev V. Year-round distribution of white-chinned petrels from South Georgia: relationships with oceanography and fisheries. Biol. Conserv. 2006;129:336–347. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.10.046 [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R.A., Croxall J.P., Silk J.R.D., Briggs D.R. Foraging ecology of albatrosses and petrels from South Georgia: two decades of insights from tracking technologies. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2008;17:S6–S21. doi:10.1002/aqc.906 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S.J., Penny W.D. Variational Bayes for generalized autoregressive models. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002;50:2245–2257. doi:10.1109/TSP.2002.801921 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S., Guilford T., Rezek I., Biro D. Positional entropy during pigeon homing I: application of Bayesian latent state modelling. J. Theor. Biol. 2004;227:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.07.002. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer S.A., Tremblay Y., Awkerman J.A., Henry W.R., Teo S.L.H., Anderson D.J., Croll D.A., Block B.A., Costa D.P. Comparison of light- and SST-based geolocation with satellite telemetry in free-ranging albatrosses. Mar. Biol. 2005;147:833–843. doi:10.1007/s00227-005-1631-8 [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer S.A., et al. Migratory shearwaters integrate oceanic resources across the Pacific Ocean in an endless summer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12799–12802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603715103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603715103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S., Thompson G., Perrins C.M. A census of the Manx shearwater on Skomer, Skokholm and Middleholm, West Wales. Bird Study. 2001;48:330–340. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K.R. Manx shearwater Puffinus puffinus. In: Wernham C., Toms M., Marchant J., Clark C., Siriwardena G., Baillie S., editors. The migration atlas. T. & A. D. Poyser; London, UK: 2002. pp. 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Weimerskirsch H., Doncaster C.P., Cuenot-Chaillet F. Pelagic seabirds and the marine environment: foraging patterns of wandering albatross in relation to prey availability and distribution. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1994;255:91–97. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0013 [Google Scholar]

- Weimerskirch H., Bonadonna F., Bailleul F., Mabille G., Dell'Omo G., Lipp H-P. GPS tracking of foraging albatrosses. Science. 2002;295:1259. doi: 10.1126/science.1068034. doi:10.1126/science.1068034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R.P., Ducamp J.J., Rees G., Culik B.M., Niekamp K. Estimation of location: global coverage using light intensity. In: Priede I.M., Swift S.M., editors. Wildlife telemetry: remote monitoring and tracking of animals. Ellis Horward; Chichester, UK: 1992. pp. 131–134. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Both the unsupervised and supervised methods presented in the paper are underpinned by Gaussian mixture models, and the detailed logic behind our methods is explained here.