Abstract

The Network Support Project was designed to determine if a treatment could lead patients to change their social network from one that supports drinking to one that supports sobriety. This study reports two-year posttreatment outcomes. Alcohol dependent men and women (N=210) were randomly assigned to one of three outpatient treatment conditions: Network Support (NS), Network Support + Contingency Management (NS+CM), or Case Management (CaseM, a control condition). Analysis of drinking rates indicated that the NS condition yielded up to 20% more days abstinent than the other conditions at two years posttreatment. NS treatment also resulted in greater increases at 15 months in social network support for abstinence, as well as AA attendance, and AA involvement, than did the other conditions. Latent growth modeling suggested that social network changes were accompanied by increases in self-efficacy and coping that were strongly predictive of long-term drinking outcomes. The findings indicate that a network support treatment can effect long-term adaptive changes in drinkers' social networks, and that these changes contribute to improved drinking outcomes in the long-term.

Keywords: Alcoholism, Social Support, AA, Cognitive-behavioral treatment, Network Support

It has often been noted that the most significant problem related to treatment of alcohol dependence is not the attainment of initial abstinence, but relapse following treatment. Marlatt (1985) estimated that fully one-third of treated individuals relapse in the first 90 days after completion of treatment. In a review of treatment effectiveness, Nathan (1986) reported that one to two years after treatment less than half of patients maintain sobriety. In a review of multisite studies, Miller, Walters and Bennett (2001) noted that approximately 65% of patients continued to drink one year after alcoholism treatment. Despite increased attention to the problem of relapse, few interventions have been able to effectively counter this phenomenon.

One approach to this problem has been the development of treatments intended to change drinkers' social networks so that they are more supportive of abstinence and less supportive of drinking. The social network has long been regarded as an important locus of reinforcement for drinking behavior (e.g., Steinglass & Wolin, 1974). Longabaugh and Beattie (Beattie & Longabaugh, 1999; Longabaugh & Beattie, 1986) coined the term “network support for drinking,” referring to the degree to which people in one's environment encourage drinking. Network support for drinking has been found to be predictive of poor treatment outcome (Havassy, Hall & Wasserman, 1991, Longabaugh et al., 1993; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997).

Alternatively, networks that promote sobriety can also affect drinking rates. The most obvious example of such a network is the fellowship of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). Several studies support the efficacy of AA or similar groups in reducing alcohol use. Emrick, Tonigan and Montgomery (1993) concluded that AA members achieve abstinence at a higher rate than do professionally treated alcoholics, and that AA participants who are more active in the fellowship program fare better than less active participants. Moos & Moos (2006), in a long-term study, concluded that some of the association between treatment and 16-year outcomes appeared to be due to participation in AA. Naturalistic studies by Kaskutas and Bond (Kaskutas, Bond & Humphreys, 2002; Bond, Kaskutas, & Weisner, 2003) indicate that AA effects are partly mediated by the changes that occur in patients' social networks, particularly changes in network support for drinking.

For the most part, however, outpatient social network-based approaches to treatment have not been widely adopted (e.g., Galanter, 1986; 1999). Perhaps the most ambitious attempt to change the social milieu is the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA; Hunt & Azrin, 1973; Meyers & Miller, 2001; Sisson & Azrin, 1989). CRA involves reinforcing the alcoholic's sobriety, developing sober recreational and social activities, and seeking employment (Meyers & Smith, 1995). Although CRA is cited as an efficacious approach to treatment (e.g., Miller, Wilbourne, & Hettema, 2003), its use is not widespread, possibly because of the effort required to implement such a comprehensive intervention. Additionally, its complexity makes it difficult to determine what features make it effective (see Roozen et al, 2004). No studies of long-term efficacy of CRA have been published.

The United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial Social Behaviour and Network Therapy study (UKATT SBNT; Copello et al, 2002) was an effort to identify, expand, and mobilize drinkers' network of family, friends and acquaintances. Both SBNT and a comparison motivational enhancement condition decreased drinking and drinking-related problems at 12 months, with no differences between conditions (UKATT, 2005). The authors did not report, however, whether SBNT acted on the social network as planned, nor if changes in social network were related to outcomes. As with CRA, no evidence of long-term efficacy has been provided.

In Project MATCH, those with high network support for drinking who had been assigned to the Twelve Step Facilitation (TSF) intervention had better outcomes than those assigned to Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) (Longabaugh, Wirtz, Zweben, & Stout, 1998). In contrast, for patients whose social network did not support continued drinking, AA involvement had less impact on outcome. The results suggested that a treatment that encourages a change of social network, from one that supports drinking to one that supports sobriety, will be effective, especially for those whose pretreatment environment is supportive of drinking.

Network Support treatment, based on the Project MATCH TSF treatment, is less comprehensive than CRA. This manualized, 12-week, individually delivered treatment (Litt, Kadden, Kabela-Cormier, & Petry, 2007) focuses on helping alcohol-dependent patients change their social network from one supportive of drinking to one supportive of abstinence. It is similar to the UKATT SBNT treatment, but is more reliant on enhancing involvement in AA and other established social infrastructures to change the social network.

Alcoholic patients from the community were randomly assigned to one of three treatment conditions: Network Support (NS), Network Support + Contingency Management (NS+CM), or a Case Management control condition (CaseM). We hypothesized that a network support intervention would result in more adaptive change in social networks than would Case Management, and that changes in the social network would predict drinking outcomes.

Initial results largely supported these hypotheses. Drinking rates of 186 participants at 12 months posttreatment indicated that both Network Support conditions yielded better outcomes than CaseM. Analyses of social network variables at posttreatment indicated that the NS conditions did not reduce social support for drinking relative to CaseM, but did increase social support for abstinence and AA involvement, both of which were significantly correlated with drinking outcomes. The addition of just one abstinent person to a social network increased the probability of abstinence for the next year by 27%. The findings suggested that drinkers' social networks can be changed by a treatment that is specifically designed to do so, and that these changes contribute to improved drinking outcomes (Litt et al., 2007).

An additional question raised by the initial study concerns the means by which abstinent social supports encourage reduction of drinking. Although never tested specifically, one possibility is that the effects of network supports may be in part mediated by coping skills and by self-efficacy. Both self-efficacy for abstinence and coping skills acquisition have been among the most potent predictors of outcome in a variety of treatment studies (e.g., Litt, Kadden, Cooney & Kabela, 2003). Non-drinking supports would serve to reinforce abstinence and to model abstinent behavior, which should result in increased self-efficacy for coping and abstinence (e.g., Bandura, 1986).

The central aim of this project was to determine if a treatment for alcohol dependence can effect results that endure over time. The current paper presents the 27-month follow-up of patients treated in the Network Support Project. The long-term follow-up allowed us to examine the hypotheses that: (1) the increases in network support for sobriety seen in the Network Support treatments, compared to CaseM, would persist through the 2-year posttreatment follow-up, and (2) that the network changes would be associated with sustained reduction in drinking relative to baseline levels. Additionally we examined a number of mechanisms by which network support might improve drinking outcomes, including enhancement of coping and of self-efficacy for abstinence. This long-term follow-up is the first study of a network support intervention to examine sustained effects.

Methods

The following is a summary of methods and procedures. Complete details regarding these aspects of the study can be found in Litt et al. (2007).

Participants

The participants were 210 men and women, recruited from the community. Participants had to be at least 18 years old, meet DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence or abuse, and be willing to accept random assignment to any of the three treatment conditions. Individuals were excluded if they had acute medical or psychiatric problems requiring inpatient treatment (e.g., acute psychosis, or suicide/homicide risk), current dependence on drugs (except nicotine and marijuana), intravenous drug use in the previous 3 months, reading ability below the fifth grade level, lack of reliable transportation to the treatment site, or excessive commuting distance. Individuals were excluded if they denied any drinking in the 60 days prior to intake, if they were already engaged in substance abuse treatment, or if they had attended more than three AA meetings in the prior month.

The participants (58% male) had a mean age of 45 years (SD = 11.4), and were 86% White, 8% Black, 4% Hispanic, and 2% other. Their mean years of schooling was 13.7 (SD = 2.1), 71% were employed at least part time outside the home, and 51% were living with a spouse or partner. All met criteria for alcohol dependence (99%) or abuse (1%), drank on average 72% of days in the 3 months prior to intake, and had a mean of 1.3 prior treatments for alcohol dependence (SD = 3.3). Assignment to treatment was as follows: NS (n=69); NS+CM (n=71); and CaseM (n=70). At the last follow-up, 27 months post intake, 172 patients (82%) were interviewed. A flow diagram of participants through the last follow-up is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing flow of participants through each stage of study up to 27 month follow-up.

Measures and Instruments

Diagnostic Interview

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient edition, version 2.0 (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon & Williams, 1996), was used to determine whether participants met inclusion/exclusion criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, drug dependence, and psychotic symptoms in the 90 days prior to the intake interview.

Drinking outcome data

Drinking data at baseline and at follow-ups were collected using the Form-90 structured interview (Miller & DelBoca, 1994). The Form-90 has good test-retest reliability, and validity for verifiable events (Tonigan, Miller & Brown, 1997).

Verification of self-reports of drinking

Collateral reports were used for one-third of participants (randomly selected) to verify self-reports of use vs. non-use of substances. Agreement between collaterals and patients regarding drinking at months 18 and 24 was kappa > .90 (p < .001).

Psychosocial Outcome

The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC; Miller, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 1995), was used to assess problems related to drinking, including health, legal difficulties, and social relations. Internal reliability of the subscales in this study ranged from alpha = .65 to .85. The DrInC Total score had an internal reliability alpha = .85.

Treatment process variables: Network support

Network support for drinking and for abstinence was measured using the Important People and Activities Instrument (IPA; Clifford & Longabaugh, 1991). The IPA is a structured interview that asks patients to identify those people with whom they spent the most time in the previous 12 months. For each person identified, the patient specifies the nature of the relationship (e.g., spouse, friend, co-worker), duration of the relationship, frequency of contact, the drinking behavior of each person (frequency and quantity), and the person's behavior with respect to the patient's drinking (neutral, supportive of drinking, supportive of abstinence). The IPA was chosen because of the ability of its subscales to predict alcohol-related outcomes (e.g., Zywiak, Longabaugh, & Wirtz, 2002). Five subscales developed for use in Project MATCH (Project MATCH Research Group, 1993) were used in the present study: Social Support for Drinking, Behavioral Support for Drinking, Attitudinal Support for Drinking, Behavioral Support for Abstinence, and Attitudinal Support for Abstinence.

Social Support for Drinking comprised two variables: the mean drinking status (from 1=abstainer to 5=heavy drinker) of the persons in the participant's social network plus the mean of those persons' reactions to the participant's drinking (from 1 = “left the room” to 5 = “encouraged” drinking). Behavioral Support for drinking was the proportion of heavy drinkers in the participant's social network (i.e., modeled drinking behavior). Attitudinal Support for drinking was calculated by taking the mean of the reactions to drinking of the top four persons on the participant's list of important people. Internal reliabilities of the Social Support for Drinking and the Attitudinal Support for Drinking variables exceeded α = .70 at all follow-ups.

Behavioral Support for Abstinence was the proportion of people in the network who were abstinent. Attitudinal Support for abstinence was calculated by taking the mean of the reactions to not drinking of the top four persons on the participant's list of important people (with reactions scaled from 1 = “left the room” to 5 = “encouraged” non-drinking). Internal reliability of Attitudinal Support for Abstinence at all follow-ups exceeded alpha = .66. An additional variable, Number of Abstinent Friends in the Social Network, was the number of nondrinking persons in the social network that the respondent interacted with at least once per week. The intercorrelations of the network support variables were in the range of .2 to .6 (except for the correlation of Behavioral Support for Abstinence with Number of Abstinent Friends, which correlated at r = .8), indicating that these variables represented related, but not redundant, constructs.

Given the focus in the current study on using AA as a social support network, level of involvement in AA was an important process variable. The Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement Scale (AAI; Tonigan, Connors, & Miller, 1996) was used to measure level of involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous at baseline and at the in-person follow-ups. The AAI is a 16-item self-report inventory that measures lifetime and recent attendance and involvement in AA (e.g., self-identification of oneself as a member of AA, phoning other AA members, acting as an AA sponsor). The AAI subscale used for these analyses employed the 10 yes-no items of the full scale, had a range from 0 to 10, and an internal reliability exceeding α = .79 at all follow-ups. These items were used because they tended to produce a more reliable scale than the full set of items. Self-reports of number of AA meetings attended prior to intake and at follow-ups (log-transformed) were also used as process variables. Because of the high rate of non-attendance in AA we also evaluated a variable called AA Participation, defined as any attendance at AA in the previous 90 days versus no attendance.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy for abstinence has been a significant mediator of alcohol treatment outcomes (e.g., Litt, et al., 2003). Self-efficacy was measured using the Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale (AASE; DiClemente, Carbonari, Montgomery, & Hughes, 1994), which asks about temptation to drink and confidence to resist drinking in 20 different drinking situations. The self-efficacy score was computed by subtracting the temptation score from the confidence score. Internal reliabilities at all in-person follow-ups exceeded α = .95.

Coping skills

The Coping Strategies Scale (CSS; Litt et al., 2003) was used to assess coping skills, to determine if increasing network support for abstinence led to enhanced coping. Subjects rated the frequency (from 0 = never to 4 = frequently) of utilizing each of 59 strategies to resist drinking in the prior 3 months. The CSS total score was computed by summing the ratings of the 59 items, and the internal reliability exceeded α = .96 at each of the follow-ups.

Procedure

Recruitment and Initial contact

Participants were recruited through the use of newspaper and radio advertisements, and through other programs at our university medical center. Callers were first evaluated on the telephone with a brief screening procedure and were either excluded (and referred elsewhere for treatment), or scheduled for an intake interview. The final decision about eligibility was made at the intake interview, after completion of the SCID-I/P (to determine presence of alcohol dependence and exclusionary diagnoses). Those who were eligible, and agreed to be randomly assigned to treatment, reviewed and signed an IRB-approved consent form and completed the intake assessment. All participants were asked to give the name of a collateral (usually a spouse or close friend) who would be able to verify his/her level of drinking and his/her location, and one-third of those were later contacted at follow-ups. Participants were assigned to treatment using an urn randomization procedure (Stout et al., 1994) that balanced the three groups for gender, age, ethnicity, alcohol dependence, and lifetime involvement with AA.

Data collection procedures

Trained B.A.-level research assistants conducted the pretreatment and follow-up assessments. Because slightly different follow-up procedures were used for different treatments, research assistants could not be blinded to treatment condition. In-person interviews were conducted at months 3 (posttreatment), 9, 15, 21, and 27. Assessments at months 6, 12, 18 and 24 were conducted by telephone. Participants were compensated $40 for attending the initial intake assessment, $50 for each in-person follow-up assessment, and $20 for each telephone follow-up. If an in-person interview was not possible a telephone interview was conducted. At the 21-month and 27-month follow-ups 79% and 76% of the interviews were conducted in person, respectively.

Treatment Interventions

Treatment was delivered by Master's level therapists with at least 5 years experience treating alcohol dependence. Treatment was conducted in 12 weekly 60-minute outpatient sessions, employing detailed therapist manuals. Participants presenting with a breathalyzer reading above .05 were rescheduled. Overall, patients attended an average of 8.7 sessions, with no differences between treatment conditions.

Case Management (CaseM)

The Case Management intervention was based on that used in the Marijuana Treatment Project (Steinberg et al., 2002), and provided an active control condition. The therapist and participant used a problem checklist to identify problems in several domains that could be barriers to abstinence, including psychiatric, interpersonal (family, childcare, and other social issues), medical, employment, educational, financial, housing, legal, and transportation. The participant and therapist developed goals, and identified resources to address the goals using a comprehensive guide to local services. The role of the therapist was to explore the relationship between identified problems and drinking, monitor progress towards goal attainment, and support participants' efforts to reach their goals. Efforts were made to minimize overlap with the NS and NS+CM treatments by avoiding recommendations regarding social support or skills development. Attendance at AA was neither encouraged nor discouraged for CaseM participants.

Network Support Intervention (NS)

The Network Support Intervention was intended to help patients change their social support networks to be more supportive of abstinence and less supportive of drinking. NS was based on the Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) treatment created for Project MATCH (Nowinski, Baker & Carroll, 1992), and was designed to use AA as an efficient means to engage patients in a supportive abstinence-oriented social network. The program consisted of 6 core sessions, plus 6 elective sessions that were chosen by the therapist and the patient together. Core topics included a Program Introduction, Acceptance (of alcoholism as a problem), Surrender (giving up the idea of managing without support), Getting Active (changing one's social network), People, Places and Things (stimulus control of drinking), and Termination. Elective topics included: Enabling, Sober Living, Increasing Pleasant Activities, and conjoint sessions with the participant's spouse or partner. Each session included assignment of recovery tasks (homework) geared toward expanding the sober social network, and included family, social/recreational, educational and employment activities.

Although the NS treatment was based on Project MATCH TSF, the emphasis was shifted to using AA as a means of changing one's overall social support network, including avoiding drinking friends and acquiring non-drinking friends. AA-specific philosophy and focus on a higher power were downplayed, and attendance at AA was presented as a way to avoid drinking, make new acquaintances, and derive enjoyment from activities other than drinking. If a patient was adamantly opposed to attending AA (about 20% of patients), the emphasis on AA was dropped. In all cases other social networks were also explored and encouraged.

Network Support Intervention + Contingency Management (NS+CM)

Participants in this condition received the same Network Support treatment as described above. In addition, reinforcements were provided contingent upon completion of assigned recovery tasks between sessions. These included attendance at AA meetings, having coffee with a non-drinking friend, signing up for a college class, etc. (see Petry, Tedford, & Martin, 2001). Verification of task completion consisted of receipts or signed slips with the name and phone number of the person providing verification.

The contingency management portion of this condition was adapted from Iguchi, Belding, Morrel, and Lamb (1997) and Petry et al. (2000), and used a fishbowl-drawing procedure for determining amount of reinforcement (Petry & Martin, 2002). Participants earned drawings from the fish bowl if they provided verification of completed network building assignments. Half of the slips in the fishbowl could be redeemed for services or merchandise. During the 12 weeks of study participation a maximum of 234 drawings could be earned. Patients in the NS+CM condition earned on average 56 draws and redeemed $250.00 worth of prizes.

Data Analysis

The primary drinking outcome variables derived from the Form-90 were Proportion of Days Abstinent (PDA) and Continuous Abstinence for the 90-day period prior to each follow-up. PDA data were arcsine transformed to decrease the inherent skewness of proportion data (Winer, 1971). The DrInC Total score was the primary psychosocial dependent variable. A measure of drinking intensity, Drinks per Drinking Day (log transformed), was also examined as a secondary outcome variable. Dependent variables were correlated with each other at about the r = .4 level.

Linear mixed modeling (Proc MIXED; SAS Institute, 1999) was used to analyze the continuously scaled dependent variables over time as a function of treatment condition. The mixed modeling procedure employs maximum likelihood estimation to calculate parameter estimates, thus taking advantage of all data collected without imputing missing data. In these analyses Treatment condition was treated as a fixed effect. Time (measured in months since baseline) was treated as a fixed, repeated effect, and the intercept was included as a random effect. An autoregressive (ar1) error covariance structure was adopted on the basis of accepted fit criteria (-2RLL, AIC; Judge et al., 1985). Post-hoc contrasts were used to detect between-treatment differences if Treatment X Time interactions appeared.

A generalized estimating equations (GEE; Proc GENMOD, SAS Institute, 1999) model was used to analyze the effect of treatment condition on the dichotomously scaled 90-day abstinence rate prior to each of the follow-up points, with pretreatment PDA (transformed) as a covariate. A similar model was used to evaluate AA participation (any attendance, yes or no) by condition.

Linear mixed models were used to determine the effect of treatment over time on the AA Involvement and attendance variables (log transformed), on the five IPA subscales, and on Number of Abstinent Friends in the Social Network. Because we had specific hypotheses as to how the treatments should influence the IPA and AA variables, planned contrasts were included in these analyses. One contrast compared the NS treatment with Case Management, and the other compared the two NS treatments. It was expected that NS would yield greater abstinence orientation in the social network than would CaseM, and that NS+CM would yield more network change than would NS. Similar analyses were used to evaluate the effects of treatment on self-efficacy and on coping, which we believed would be significant mediators of treatment effects based on our past findings (e.g., Litt et al., 2003).

Finally, latent growth modeling (LGM) using structural equation modeling procedures was used to evaluate the effects of treatment and possible mediators of treatment on PDA outcomes over the 27 months of follow-up. A bootstrapping resampling procedure was used to estimate model test statistic p values and parameter standard errors under the nonnormal data conditions in this dataset (Arbuckle, 2006). A total of 153 cases with complete data were available for these analyses. Those who were eliminated from these analyses on the basis of missing data did not differ from those included in the LGM on age, sex, ethnicity, education, marital status, baseline drinking, alcohol dependence, size of social network, AA involvement, treatment attendance, or treatment assignment.

Models were built sequentially, starting with a basic latent growth model comprising the PDA variables over time, modeled as slope and intercept. Different sets of mediators were tested in turn. As per the recommendations of Bollen and Long (1993), models were considered to fit the data if the model chi-square was not significant, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was at least .97, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was below .10. Models were tested on an iterative basis, and individual paths were added or removed on the basis of modification indices (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1984).

Results

Treatment Effects on Drinking and Drinking Consequences Outcomes

Effects of treatment on outcome measures are shown in Figure 2. The analysis of PDA (transformed) through 27 months indicated no main effect for Treatment [F (2, 1616) = 0.82], a significant effect for Time [F (9, 1616) = 80.36; p < .001], and a significant Treatment X Time interaction [F (18, 1616) = 3.95; p < .02]. Analysis of post-hoc Treatment contrasts indicated that the NS condition yielded significantly greater PDA than either of the other conditions through the 27 month follow-up [Fcontrast (1, 1616) = 5.33; p < .02]. The treatment effect contrast NS v. NS+CM had a moderate effect size (average d = .28), with the NS condition yielding up to 20% more days abstinent than the other conditions at 2 years posttreatment. Levels of PDA (detransformed) by treatment condition are shown in panel A of Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Effects of treatment on drinking outcomes and on drinking consequences.

Figure 2, panel B, shows the levels of continuous abstinence for the 90 days prior to each follow-up. Abstinence rates in the NS condition reached 40% at 12, 15, 18, 24, and 27 months. The GEE analysis yielded no significant main effect for Treatment condition, a main effect for Time [χ2 (8) = 18.85; p < .02], and no Treatment X Time interaction. An a-posteriori contrast comparing the NS condition versus CaseM plus NS+CM, however, was significant [χ2 (1) = 4.66; p < .03], indicating an overall advantage for the NS condition. This contrast had a moderate effect size of h=.30.

Figure 2, panel C, shows the mean DrInC negative consequences total scores by treatment condition for each of the follow-up points at which the measure was administered. Negative consequences declined over time in all treatments. A linear mixed model analysis was used to examine differences in DrInC Total Score as a function of treatment condition over the 27 months of follow-up. PDA at baseline (transformed) served as a covariate. Results indicated no main effect for Treatment [F (2, 789) = 1.50], a significant effect for Time [F (5, 789) = 75.12; p < .001], and no significant Treatment X Time interaction [F (10, 789) = 1.08]. Equivalent results were found when the same analyses were conducted on the individual DrInC subscales.

Figure 2, panel D shows the means of Drinks per Drinking Day by treatment assignment over the follow-ups. Mixed model analysis yielded no main effect for Treatment [F (2, 1616) = 1.13], a significant Time effect [F (9, 1616) = 52.03; p < .001], and no Treatment X Time interaction [F (18, 1634) = 1.53].

Treatment Effects on Changes in Social Network

As seen in Table 1, no main effects for Treatment emerged in the analyses of any of the social network variables tested. Effects for Time, and/or Treatment X Time, were found for: Behavioral Support for Drinking, Behavioral Support for Abstinence, Attitudinal Support for Abstinence, and Number of Abstinent Friends. Examination of least-squares means suggested that Behavioral Support for Drinking decreased significantly in all treatment conditions from baseline to posttreatment, and remained low out to the 27-month follow-up point (results not shown).

Table 1.

Results of Repeated Measures Mixed Model Regression Analyses on Network Support Variables through 27-month follow-up. The Values Shown Are F values For Each Effect.

| Variable | Treatment (df = 2, 207) | Time (df = 3, 207) | Time X Treatment (df = 6, 207) | Time X Treatment Contrast Results (df = 1, 207) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS v. CaseM | NS v. NS+CM | ||||

| Social Support for Drinking (range 2 - 10) | 0.35 | 2.27 | 1.07 | 0.68 | 0.27 |

| Behavioral Support for Drinking (range 0 - 1) | 1.73 | 8.01*** | 0.81 | 0.95 | 0.75 |

| Attitudinal Support for Drinking (range 1 - 5) | 0.08 | 0.43 | 1.09 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| Behavioral Support for Abstinence (range 0 - 1) | 0.35 | 2.72* | 3.86* | .37 | 2.64 |

| Attitudinal Support for Abstinence (range 1 - 5) | 1.63 | 1.18 | 1.32 | 3.84* | 0.99 |

| Number of Abstinent Friends in Social Network | 0.23 | 1.47 | 3.80* | 3.45* | 2.95 |

Note:

p < .05

p < .001

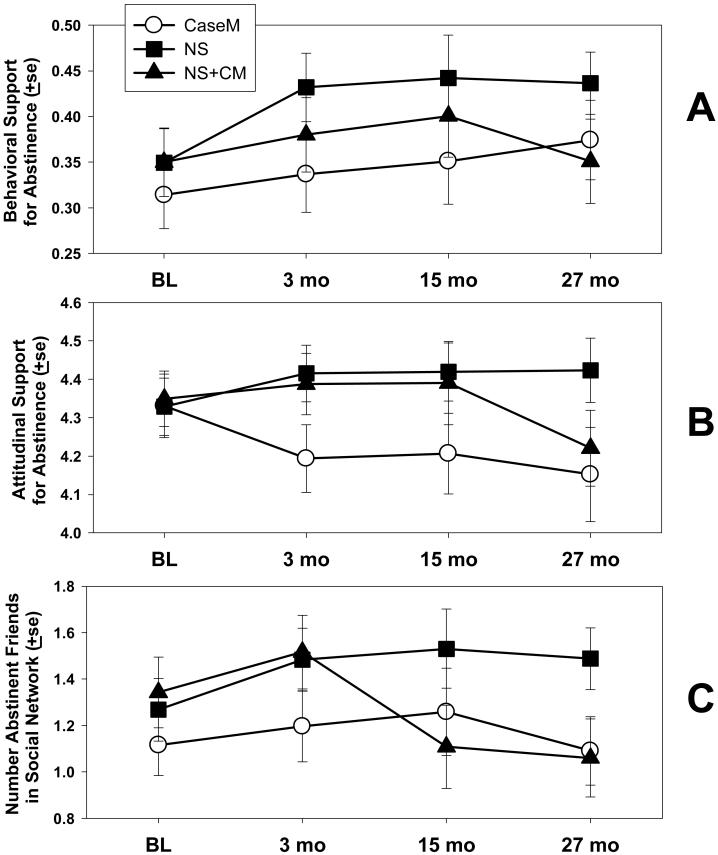

Three variables showed Treatment X Time interactions, either overall or in tests of contrasts. Scores on Behavioral Support for Abstinence increased in the two Network Support conditions from baseline through 15 months, whereupon scores in the NS+CM condition declined and scores in the CaseM condition rose minimally out to 27 months (see Figure 3, panel A). Attitudinal Support for Abstinence (panel B) followed a similar pattern. Although the overall Treatment X Time interaction was not significant, a significant Treatment contrast of NS v. CaseM did emerge, such that Attitudinal Support levels were higher over time for the NS conditions (see Table 1 and Figure 3, panel B). In the NS condition, the Number of Abstinent Friends in the Social Network increased through 15 months and then leveled off, but dropped at 15 months for those in the NS+CM condition. Figure 3, panel C, shows a significant Treatment X Time interaction, and a significant contrast of NS v. CaseM.

Figure 3.

Effects of treatment on selected measures of social network change (measured using the IPA; Clifford & Longabaugh, 1991).

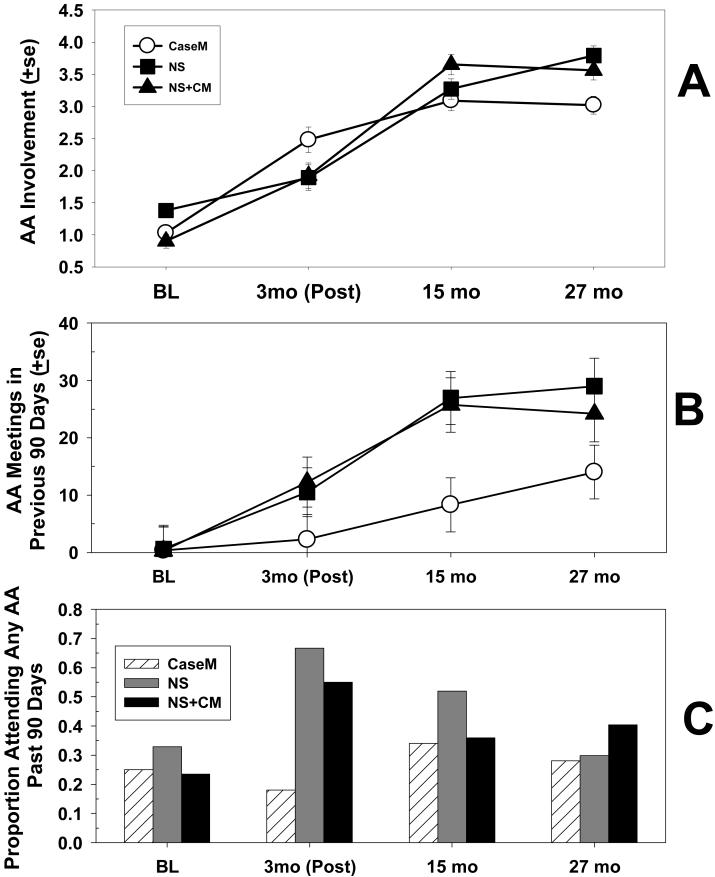

Figure 4 shows levels of AA variables over the follow-ups by treatment. AA Involvement increased steadily up to 15 months, but was relatively flat in the NS+CM and CaseM conditions from months 15 to 27 (Figure 4, panel A). The mixed model analysis showed a non-significant main effect for Treatment [F (2, 475) = 2.81; p = .06], a significant Time effect [F (3, 475) = 198.49; p < .001], and a significant Treatment X Time interaction [F (6, 475) = 3.05; p < .01]. Time X Treatment contrasts indicated that the NS condition yielded significantly greater AA Involvement scores from posttreatment through the follow-ups than did the CaseM condition [F (1, 475) = 5.18; p < .05], but the two NS conditions did not differ from one another. The effect size for the NS v. CaseM contrast was moderate, d = .68.

Figure 4.

Effects of treatment on AA measures.

Mixed model analysis on AA attendance indicated a main effect for Treatment [F (2, 476) = 3.04; p < .05], a main effect for Time [F (3, 476) = 1.41; p < .001], and a significant Treatment X Time interaction [F (6, 476) = 4.19; p < .05]. AA attendance in the NS condition averaged over 25 meetings in the prior 90 days at the 27 month point, versus just over 13 for CaseM participants, resulting in a significant contrast of NS v. CaseM [F(1, 476) = 6.07; p < .01]. The effect size of this contrast was d = 0.8. The two Network Support conditions did not differ from each other (see Figure 4, panel B).

Rates of AA participation (i.e., any attendance) by condition show somewhat different results (Figure 4, panel C). The GEE model (N=708) showed a significant effect for Time [Wald χ2 (3) = 18.91; p < .001], for Treatment [Wald χ2 (2) = 8.63; p < .051], and for Treatment X Time [Wald χ2 (6) = 34.04; p < .051]. Post-hoc simple chi-square tests indicated that the only between-treatment differences occurred at posttreatment; NS participants were more likely to attend at least one AA meeting than were those in the other conditions. Rates of any attendance in AA declined in all conditions from posttreatment through 27 months.

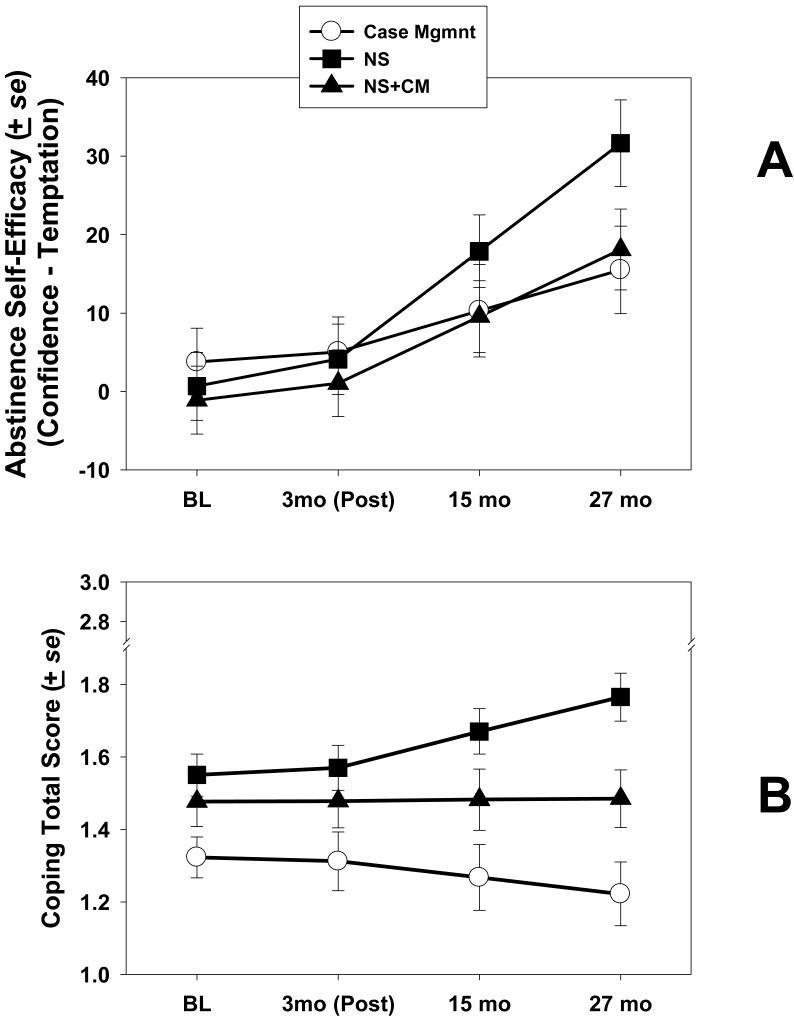

Treatment Effects on Other Mediators

Alcohol abstinence self-efficacy over time was analyzed using mixed models as described above. Results showed no main effect for Treatment [F (2, 445) = .85], a significant main effect for Time [F (3, 445 = 56.35; p < .001], and a significant Treatment X Time interaction [F (6, 445) = 2.91; p < .01]. Self-efficacy increased over time in all three treatment conditions, but the increase for NS patients was much steeper from months 15 through 27 than in the other conditions (see Figure 5, panel A).

Figure 5.

Effects of Treatment on Self-Efficacy and Coping Skills Scale scores.

Similar analyses were conducted on Coping Scale total scores. Results showed a significant main effect for Treatment [F (2, 445) = 11.86; p < .001], a significant main effect for Time [F (3, 445 = 49.42; p < .001], and a significant Treatment X Time interaction [F (6, 445) = 3.35; p < .01]. Coping increased over time in the NS condition from months 15 through 27, but remained flat in the NS+CM condition, and actually declined somewhat in the CaseM condition from posttreatment to 27 months (see Figure 5, panel B).

Effects of Treatment and Mediators on Outcomes Over Time

Latent growth model

As a first step, an initial latent growth model (LGM) was fitted in which the slopes and intercepts of the follow-up PDA values (months 3 to 27) were modeled, with baseline PDA was used as an exogenous predictor. Several alternative forms were considered in modeling the pattern of PDA over time. Among these were models containing both linear and quadratic components (χ2=106.95; df = 42; p < .01), a piecewise model in which slopes for PDA were analyzed separately for months 3 to 15 and months 18 to 27 (χ2=99.25; df = 42; p < .01), and a piecewise model in which slopes for PDA were analyzed for months 3 to 18 and 21 to 27 (χ2=115.49; df = 42; p < .01). A linear model yielded a fit that was comparable to the other models (χ2=121.18; df = 47; p < .01).

Although the linear model was not the best fitting of those examined, it was the most interpretable, and thus a linear model was adopted, and modified through the freeing of residuals after consulting modification indices. The resulting modified growth model yielded a chi-square of 50.04; df = 37; p > .05. The fit of this model was acceptable, with a comparative fit index (CFI) of .99, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .06. Baseline PDA was a significant predictor of the PDA intercept (level at Month 3; B= 0.43; z=4.33; p < .001), but was not a significant predictor of slope. The overall slope was positive (B=.09), indicating that PDA increased modestly over time from the posttreatment point on.

Effect of treatment

The next step was to add Treatment to the LGM, as a predictor of the slope and intercept latent variables. Treatment was coded as contrast dummy variables and tested sequentially in the LGM. The best fitting model contained Treatment coded as a contrast of NS v. CaseM and NS+CM. With this treatment contrast the model had a chi-square of 54.38 (df=44; p > .10). The treatment contrast was significantly and positively associated with the intercept of PDA (B =.29; z = 2.02, p < .05), and with the slope of PDA (B =.35; z = 2.33, p < .05), indicating that NS (in contrast to the other two conditions) contributed significantly to both the level of PDA at 3 months (posttreatment), and to the increase in PDA over time.

Selection of mediating variables

Due to the limits imposed by the sample size and the complexity of the possible models, it was not possible to test all potential mediators of treatment at all time periods. To determine which mediators to keep, and from which time points, each set of variables was tested as part of the LGM. Among the IPA variables, the three variables that were sensitive to Time or to Time X treatment effects were each tested (i.e., Behavioral Support for Abstinence, Attitudinal Support for Abstinence, and Number of Abstinent Friends in the social network). Of these, the best fit to the LGM included the IPA variable Number of Abstinent Friends in the social network, at the posttreatment time point (model χ2= 69.32; df= 63; p > .20; CFI=.99; RMSEA=.03). In this model the Treatment contrast significantly predicted Number of Abstinent Friends at posttreatment, which in turn predicted both slope and intercept of PDA, while the Treatment-to-PDA paths were reduced to nonsignificance.

When AA-related variables were tested in the same way, the continuous measure of AA attendance at posttreatment was the best predictor of PDA slope and intercept (though no model provided a good fit to the data). With AA meeting attendance in the model, the relationships between the Treatment contrast dummy variable and PDA slope and intercept were reduced to nonsignificance.

The self-efficacy variables were also tested in the same way. The only admissible model contained the self-efficacy variables at posttreatment and at 15 months. The model containing these variables was an excellent fit to the data (model chi-square = 61.51; df= 52; p > .10; CFI=.99, RMSEA=.05). Self-efficacy at 15 months was a significant predictor PDA slope and was predicted by PDA intercept. As with the IPA and AA variables, the relationships between Treatment and PDA slopes and intercepts disappeared when the self-efficacy variables were in the model.

The best fitting of the Coping score models included only Coping Total Score at 15 months (model chi-square = 99.25; df= 53; p > .07; CFI=.97; RMSEA = .06). Coping at 15 months predicted PDA slope, and was predicted by PDA intercept. With 15-month Coping in the model, the relationships between Treatment and PDA slopes and intercepts disappeared. Therefore, Coping Total Score at 15 months was retained for the final model.

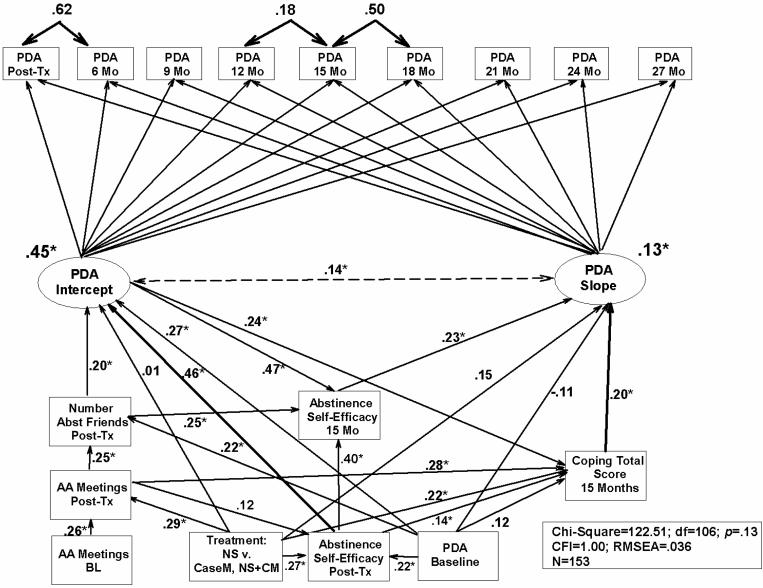

Final structural model

Figure 6 shows the final structural model containing the mediating variables that emerged in the preceding analyses. The model was constructed using all the variables described thus far. Initially, a saturated model was constructed in which all possible paths were included. (Paths pointing backward in time were not allowed.) Modification indices were consulted to adjust the model to optimize fit with the data. The resulting model was an excellent fit to the data (model chi-square = 122.51; df= 106; p = .13; CFI=1.00, RMSEA=.036). As shown in this model, direct paths from the treatment contrast term to the PDA slope and intercept latent variables were not significant. The effect of treatment appears to have been mediated through effects on AA attendance at posttreatment, Number of Abstinent Friends in the social network (measured at posttreatment), coping skills at 15 months, and self-efficacy at posttreatment and at 15 months. In addition, the mediating variables were influenced to some extent by baseline drinking. Finally, self-efficacy at 15 months, which appeared as a strong predictor of both PDA slope, was itself a function of posttreatment drinking, posttreatment self-efficacy, treatment condition (being higher in NS), and Number of Abstinent Friends.

Figure 6.

Diagram showing final structural equation model of treatment effects and mediators on slope and intercept of outcome, measured as Proportion Days Abstinent (PDA) every 3 months over 27 months. Post-Tx = posttreatment; NS=Network Support; CaseM=Case Management; NS+CM=Network Support + Contingency Management; df=degrees of freedom; CFI=Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA=Root Means Square Error of Approximation. Dotted line indicates a covariance estimate, rather than a regression coefficient. Note: * p < .01.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that a treatment designed to change the social network can yield favorable outcomes in the long-term. Patients in the Network Support condition reported an average of 80% abstinent days two years after treatment had ended (versus just over 60% for the other two conditions), and 40% were reporting complete abstinence in the 90 days preceding their two-year follow-up (versus under 30% for the other two conditions).

Analysis of changes in social network variables and in use of AA also supported the utility of the Network Support treatment. As noted in our earlier report (Litt et al., 2007), changes in the social network took the form of increases in behavioral and attitudinal support for abstinence, and increase in abstinent friends, rather than decreases in support for drinking. That is, participants in the Network Support treatment tended to add non-drinking members to their social networks rather than eliminate drinkers, a change in network composition that persisted for two years following treatment. This resulted in a small increase in Network size for NS relative to the other treatments by 27 months (4.0 people v. 3.3 for NS+CM and 3.1 for CaseM).

This finding regarding the importance of non-drinking friends is similar to that of Bond et al. (2003), except they found that only the support of AA members was influential in predicting drinking rates. In the present study we were not able to determine whether new non-drinking friends were acquired through AA. Participants in this study identified new acquaintances as “friends,” and were not asked if they were friends from AA.

The Network Support treatment relied largely on AA to provide a non-drinking social network. Measures of AA use indicated that all participants, including those in CaseM, tended to increase their use of AA at posttreatment, and through the 27 month follow-up. However, the two NS conditions were more effective than CaseM at increasing mean AA attendance.

The AA attendance variable at posttreatment proved to be a better predictor of drinking outcome than the AA involvement variable. This result is at odds with findings like those of Montgomery, Miller and Tonigan (1995), perhaps due to the way that AA Involvement is measured. The largest component of AA Involvement is AA attendance. (In this sample, AA attendance and AA involvement correlated at above r = .80). When AA attendance was in the structural model, the variance attributable to AA Involvement was reduced.

It is also noteworthy that the most predictive of the AA variables was from the posttreatment time point, which corresponds to the highest rate of AA participation (i.e., any attendance at AA; see Figure 4C). NS in particular resulted in more AA attendance, but the number of patients attending AA declined as time went on. Nevertheless, the effects of NS persisted beyond that. One of those effects appears to have been continued association with new, non-drinking friends, some of whom apparently were associated with AA meetings (see Figure 6). Thus both posttreatment AA attendance and number of friends partly mediated the effect of NS treatment on PDA, particularly on the posttreatment level of PDA.

A striking finding in Figure 6 is the large impact of self-efficacy on outcome. Self-efficacy at posttreatment was the largest associate of the PDA Intercept (PDA at posttreatment), and self-efficacy at 15 months was the largest determinant of PDA slope over the 2-year follow-up period. Self-efficacy at 15 months, in turn, was largely a function of self-efficacy measured at posttreatment, and the number of abstinent friends in the social network at posttreatment. The structural model showed effects for treatment on posttreatment self-efficacy, despite the fact that this did not appear in the direct test of treatment (Figure 5A). This suggests that other variables (namely baseline PDA and AA meetings attended) played a role in eliciting this effect.

The finding that self-efficacy was a major contributor to outcome was not unexpected on the basis of earlier work. Self-efficacy has been predictive of both short-term (1 year) and long-term (3 year) alcohol treatment outcomes (e.g., Greenfield et al., 2000; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997). In addition, however, self-efficacy in the present study appeared to be an important mediator of treatment effects. This finding is somewhat less common (Maisto, Connors & Zywiak, 2000; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004), and bolsters the idea that self-efficacy is a major determinant of behavior change in alcohol treatment (see also Litt et al., 2003). This is similar to the finding of Morgenstern et al. (1997), which indicated that effects of AA on later drinking were mediated by self-efficacy. The fact that self-efficacy was a function of number of abstinent friends in the social network, suggests that social supports may be strengthening self-efficacy beliefs (e.g., Davis & Jason, 2005).

Coping score, too, was a significant predictor of outcome, and in turn was strongly predicted by AA attendance at posttreatment. Indeed, posttreatment AA attendance was a larger independent predictor of use of copings skills than was treatment type. These findings suggest that AA may be filling several needs, including encouraging the use of coping skills (and perhaps teaching them as well), and increasing confidence in one's ability to resist drinking. The Network Support treatment, then, seems to include several of the mechanisms identified by Moos (2007) in his review of effective treatment components. According to Moos, these include “support, goal direction, and structure; an emphasis on rewards that compete with substance use, a focus on abstinence-oriented norms and models, and attempts to develop self-efficacy and coping skills” (p. 109).

An unexpected finding was the relatively poor long-term performance of the NS+CM condition. Participants in this condition initially did as well as those in NS, but at the end of two years were reporting the same outcomes as those in CaseM. A clue to this finding may be found in the between-treatment results for the mediating variables, particularly self-efficacy. At posttreatment all of the treatments showed similar increases in self-efficacy. By 15 and 27 months, however, the NS condition had resulted in greater self-efficacy than the other conditions. Contingency management may have been effective as long as it was in place, but the external reinforcements it provided may not have generated increases in self-efficacy that were sustained after they were discontinued. This may be the result of attributions by participants that their abstinence behavior was externally maintained by the reinforcements received. For self-efficacy to increase, people have to attribute their accomplishments to their own efforts (Bandura, 1986).

Another potential explanation for the relatively poor effects of CM in this study may relate to the type of behavior that was reinforced. CM interventions often reinforce abstinence directly. In a study with cocaine abusing patients, contingent reinforcement of adherence to goal-related activities resulted in no benefits beyond standard care, but a CM treatment that reinforced abstinence directly improved drug use outcomes (Petry et al., 2006). Hence, it may be that reinforcing adherence to goal-related social activities in alcohol dependent patients is similarly ineffective in improving long-term outcomes.

This study has some limitations. As noted in our earlier report (Litt et al., 2007), there was no active coping skills-based treatment against which to compare the NS treatments. Consequently, there is no way to determine if NS is superior to other treatments, such as CBT. The drinking rates reported here, however, are comparable to, or better than, those in other studies reporting long-term outcomes such as Project MATCH, which reported a mean PDA of 69% and 29.4% abstinent at months 37-39 (Project MATCH Research Group, 1998). The high proportion of white participants in our study may limit the generalizability of the findings, however.

Another limitation is the fact that, for ease of interpretation, only linear models of the data were ultimately chosen for analysis. Our model showed excellent fit to the data, but only when some residual covariances were allowed to be correlated with each other, thus violating an assumption of a true unconditional growth model. The results presented in this model should, then, be viewed as suggestive rather than conclusive. Additionally, although we discuss variables as appearing to mediate the effects of treatment, in the sense that they appear to be links in a causal chain from treatment to outcome, we make no claims for having determined formal statistical mediation.

Finally, we cannot tell why we observed treatment differences for PDA and abstinence outcomes, but not for DDD and DrInC outcomes. It is a common finding that on average participants improve across multiple outcomes when they receive treatment (e.g., Donovan et al., 2005). Our failure to find treatment differences in DDD, however, may have been due to insufficient power to detect a smaller effect than that observed with PDA.

The present study indicates that a manualized treatment focused specifically on changing the social environment can lead to lasting adaptive changes in the social network of alcohol dependent patients, and that these changes are predictive of lasting improvement in drinking outcome. No other study to date has been able to demonstrate lasting effects on drinkers' social environments. As in our earlier report (Litt et al., 2007), AA attendance and increasing the number of non-drinking friends in the social network were strong (direct and indirect) predictors of outcome, appearing to result in increased abstinence in part due to effects on self-efficacy. The program, however, did not work for everyone. Almost 30% of patients in the NS conditions had 2 or fewer abstinent friends throughout the 2 years of the study, and 33% attended no AA meetings during the entire study period. The reasons for this are not clear. Additional treatm development will be needed to maximize the effectiveness of this type of intervention.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this paper were presented at the February 2006 meeting of the International Conference on the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, in Santa Fe, NM. Support for this project was provided by grants R01-AA12827 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and in part by General Clinical Research Center grant M01-RR06192 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to acknowledge Eileen Porter, William Blakey, Kara Dion, Abigail Sama, Nicole Paulin, Aimee Markward, Howard Steinberg, Patricia Gaupp, Anna Lane, and Christine Calusine for their work in the conduct of this study.

References

- Arbuckle, James L. Amos 7.0 User's Guide. SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie MC, Longabaugh R. General and alcohol-specific social support following treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:593–606. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Long SJ. Testing Structural Equation Models. SAGE Focus Edition vol. 154. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bond J, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. The persistent influence of social networks and Alcoholics Anonymous on abstinence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:579–588. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copello A, Orford J, Hodgson R, Tober G, Barrett C, UKATT research team Social behaviour and network therapy: Basic principles and early experiences. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:345–66. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MI, Jason LA. Sex differences in social support and self-efficacy within a recovery community. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:259–274. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8625-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Carbonari J, Montgomery, Hughes S. The Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy scale. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:141–148. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan D, Mattson ME, Cisler RA, Longabaugh R, Zweben A. Quality of life as an outcome measure in alcoholism treatment research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;(Suppl 15):119–139. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M. Social network therapy for cocaine dependence. Advances in Alcohol and Substance Abuse. 1986;6:159–75. doi: 10.1300/J251v06n02_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanter M. Network therapy for alcohol and drug abuse. Guilford; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S, Hufford M, Vagge L, Muenz L, Costello M, Weiss R. The relationship of self-efficacy expectancies to relapse among alcohol dependent men and women: A prospective study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:345–351. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emrick CD, Tonigan JS, Montgomery H. Alcoholics Anonymous: What is currently known? In: McCrady BS, Miller WR, editors. Research on Alcoholics Anonymous: Opportunities and alternatives. Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; Piscataway, NJ: 1993. pp. 41–76. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Havassy BE, Hall SM, Wasserman DA. Social support and relapse: Commonalties among alcoholics, opiate users and cigarette smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1991;16:235–246. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90016-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GM, Azrin NH. A community reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1973;11:91–104. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(73)90072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi MY, Belding MA, Morrel AR, Lamb RJ. Reinforcing operants other than abstinence in drug abuse treatment: An effective alternative for reducing drug use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:421–428. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL-VI user's guide. 3rd ed. Scientific Software; Mooresville, IN: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Bond J, Humphreys K. Social networks as mediators of the effect of Alcoholics Anonymous. Addictions. 2002;97:891–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Cooney NL, Kabela E. Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive-behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:118–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, Petry NM. Changing network support for drinking: initial findings from the network support project. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:542–555. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Beattie MC. Social investment, environmental support and treatment outcomes of alcoholics. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1986;(Summer):64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Beattie MC, Noel NE, Stout RL, Malloy P. The effect of social investment on treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:465–478. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Zweben A, Stout RL. Network support for drinking, Alcoholics Anonymous and long-term matching effects. Addiction. 1998;93:1313–1333. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93913133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Connors GJ, Zywiak WH. Alcohol treatment, changes in coping skills, self-efficacy, and levels of alcohol use and related problems 1 year following treatment initiation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:257–266. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention: Theoretical rationale and overview of the model. In: Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Relapse prevention. Guilford; New York: 1985. pp. 3–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Clarke JC. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny, fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:455–470. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RJ, Miller WR, editors. A community reinforcement approach to addiction treatment. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RJ, Smith JE. Clinical guide to alcohol treatment: The Community Reinforcement Approach. Guildford Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, DelBoca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form-90 family of instruments. Journal of Studies of Alcohol. 1994;12:112–118. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Walters ST, Bennett ME. How effective is alcoholism treatment in the United States? Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:211–20. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL, Hettema JE. What works? A summary of alcohol treatment outcome research. In: Hester RK, Miller WR, editors. Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches: Effective Alternatives. 3rd ed. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA: 2003. pp. 13–63. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery HA, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Does Alcoholics Anonymous involvement predict treatment outcome? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1995;12:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)00018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Participation in treatment and Alcoholics Anonymous: a 16-year follow-up of initially untreated individuals. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:735–750. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Theory-based active ingredients of effective treatments for substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Labouvie E, McCrady BS, Kahler CW, Frey RM. Affiliation with Alcoholics Anonymous after treatment: a study of its therapeutic effects and mechanisms of action. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:768–777. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan P. Outcomes of treatment for alcoholism: Current data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1986;8:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Carroll KM, Hanson T, MacKinnon S, Rounsaville B, Sierra S. Contingency management treatments: Reinforcing abstinence versus adherence with goal-related activities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:592–601. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, martin B. Low-Cost Contingency Management for Treating Cocaine- and Opioid-Abusing Methadone Patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:398–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney J, Kranzler H. Give them prizes and they will come: Contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting &Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Tedford J, Martin B. Reinforcing compliance with non-drug related activities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;20:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group Project MATCH (Matching Alcoholism Treatment to Client Heterogeneity): rationale and methods for a multisite clinical trial matching patients to alcoholism treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 1993;17:1130–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group Matching alcoholism treatment to client heterogeneity: Post-treatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group Matching alcoholism treatment to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozen HG, Boulogne JJ, van Tulder MW, van den Brink W, De Jong CAJ, Kerkhof AJFM. A systematic review of the effectiveness of the community reinforcement approach in alcohol, cocaine and opioid addiction. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson RW, Azrin N. The community reinforcement approach. In: Hester R, Miller WR, editors. Handbook of alcoholism treatment approaches: effective alternatives. Pergamon Press; New York: 1989. pp. 242–258. [Google Scholar]

- Steinglass P, Wolin S. Explorations of a systems approach to alcoholism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1974;31:527–532. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760160071015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Connors GJ, Miller WR. Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement (AAI) Scale: Reliability and norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Brown JM. The reliability of Form 90: An instrument for assessing alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:358–64. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UKATT Research Team Effectiveness of treatment for alcohol problems: Findings of the randomised UK Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT) British Medical Journal. 2005;331:541–545. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7516.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems. That was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist. 2004;59:224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak WH, Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW. Decomposing the relationships between pretreatment social network characteristics and alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]