Abstract

To study links between rapid ERP responses to fearful faces and conscious awareness, a backward masking paradigm was employed where fearful or neutral target faces were presented for different durations and were followed by a neutral face mask. Participants had to report target face expression on each trial. When masked faces were clearly visible (200 ms duration), an early frontal positivity, a later more broadly distributed positivity, and a temporo-occipital negativity were elicited by fearful relative to neutral faces, confirming findings from previous studies with unmasked faces. These emotion-specific effects were also triggered when masked faces were presented for only 17 ms, but only on trials where fearful faces were successfully detected. When masked faces were shown for 50 ms, a smaller but reliable frontal positivity was also elicited by undetected fearful faces. These results demonstrate that early ERP responses to fearful faces are linked to observers’ subjective conscious awareness of such faces, as reflected by their perceptual reports. They suggest that frontal brain regions involved in the construction of conscious representations of facial expression are activated at very short latencies.

Keywords: Consciousness, emotion, face processing, visual masking, event-related brain potentials

The study of the neural substrates of emotions has become one of the most active research areas in the neurosciences (see Adolphs, 2002, 2003; Dolan, 2002, for reviews). Emotional processes are often investigated by measuring brain responses to affective visual stimuli, such as emotional faces. The perceptual analysis of structural properties that determine face identity, and analysis of dynamic aspects, such as facial expression, eye and mouth movements, take place in fusiform gyrus and superior temporal sulcus, respectively (Hoffman & Haxby, 2000; see also Allison, Puce, & McCarthy, 2000; Haxby, Hoffman, & Gobbini, 2000, for reviews). The rapid evaluation of the emotional content of facial expression appears to be mediated by the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, while structures such as the anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex are linked to the conscious representation of perceived facial expression (cf., Adolphs, 2003). Neuropsychological evidence also suggests that the processing of facial identity and facial expression are subserved by distinct neural substrates. Focal damage to selective brain regions can leave patients with a deficiency in recognising faces, and yet spare the ability to read facial expressions of emotion (Etcoff, 1984; Posamentier & Abdi, 2003; Young, Newcombe, de Haan, Small, & Hay, 1993). On the other hand, some patients are impaired in their ability to read emotional cues from faces, but have no difficulty in identifying people (Hornak, Rolls, & Wade, 1996). Such double dissociations strongly suggest that the detection and analysis of facial emotional expression and the structural encoding of facial features for face recognition are implemented by separable and at least partially independent brain mechanisms.

Given its adaptive significance, it is often assumed that the emotional information provided by affectively salient stimuli such as facial expressions is processed even when this information is not accessible to conscious awareness. The subliminal processing of emotional stimuli might be mediated by a hypothetical subcortical pathway that sends retinal input directly to the amygdala via the superior colliculus and the pulvinar (see Pessoa, 2005, for a more detailed discussion). Evidence that emotionally salient events can be processed without awareness comes from fMRI studies demonstrating fear-specific amygdala activation during binocular suppression (Pasley, Mayes, & Schultz, 2004; Williams, Morris, McGlone, Abbott, & Mattingley, 2004), in extinction resulting from right parietal damage (Vuilleumier et al., 2002), and for masked fearful relative to happy faces (Whalen et al., 1998; Morris, Öhman, & Dolan, 1998; but see Phillips et al., 2004 for conflicting results).

The aim of the present experiment was to use event-related brain potential (ERP) measures to obtain further insights into links between conscious awareness and the processing of emotional expression. Due to their excellent temporal resolution, ERPs can be used to study the time course of emotional processing. There is now considerable evidence from depth electrode recordings and magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies in humans that discriminatory responses to emotionally salient supraliminal events can occur within 200 ms (Kawasaki et al., 2001; Krolak-Salmon, Henaff, Vighetto, Bertrand, & Mauguiere, 2004; Liu, Ioannides, & Streit, 1999). These findings are in line with ERP results, which have shown that relative to neutral faces, emotional faces trigger an early enhanced positivity over prefrontal areas (Ashley, Vuilleumier, & Swick, 2004; Eimer & Holmes, 2002; Eimer, Holmes, & McGlone, 2003; Holmes, Vuilleumier, & Eimer, 2003). This emotional expression effect usually starts within 150 ms after stimulus onset, and has been found as early as 120 ms (Eimer & Holmes, 2002). Following this early response at anterior electrodes, emotional faces also trigger a sustained positivity with a broad frontoparietal scalp distribution (Ashley et al., 2004; Eimer & Holmes, 2002), and an enhanced negativity over lateral posterior areas (Eimer et al., 2003; Marinkovic & Halgren, 1998; Sato, Kochiyama, Yoshikawa, & Matsumura, 2001; Schutter, de Haan, & Van Honk, 2004; Vanderploeg, Brown, & Marsh, 1987).

Such ERP modulations triggered by emotional facial expression have been interpreted as reflecting distinct stages in the processing of emotional faces. The early anterior positivity triggered within 150 ms after stimulus onset might be generated by prefrontal or orbitofrontal mechanisms involved in the rapid detection of facial expression (Eimer & Holmes, 2002), while the later more broadly distributed sustained positivity is likely to reflect the subsequent processing of emotional faces at higher-order decision- and response-related stages. The enhanced posterior negativity for fearful as compared to neutral faces observed at latencies beyond 200 ms post-stimulus has been attributed to the selective attentional processing of emotional faces in extrastriate visual areas. For example, Sato et al. (2001) proposed that this negativity was linked to reentrant projections from the amygdala to visual cortex, which act to enhance the perceptual awareness of emotional stimuli.

Only very few ERP studies have investigated the subliminal processing of emotional faces (but see Schutter & van Honk, 2004, for a recent study of unconscious emotional processes with EEG coherence measures). Liddell, Williams, Rathjen, Shevrin, & Gordon (2004; see also Williams et al., 2004) compared ERPs to fearful or neutral faces that were presented for 10 ms (subliminal condition) or 170 ms (supraliminal condition), and were immediately followed by a neutral face mask, while observers passively watched these stimuli. In a forced choice experiment conducted with a different set of participants, Liddell et al. (2004) found that detection performance was at chance level when masked fearful faces were presented for 10 ms. Relative to neutral faces, fearful faces triggered an enhancement of the N2 component in the subliminal condition, while supraliminal fearful faces elicited an enlarged parietal P3 component. Liddell et al. (2004) interpreted the N2 enhancement for subliminal fearful faces in terms of an automatic orienting response that is triggered independently of awareness, and the enhanced P3 for supraliminal fearful faces as reflecting the conscious integration of an emotional content into the current stimulus context.

In a recent ERP study of subliminal emotional processing (Kiss & Eimer, in press), target faces were presented for either 8 ms (subliminal trials), or 200 ms (supraliminal trials), and were immediately followed by scrambled face masks. Participants had to identify the expression of masked fearful or neutral target faces on every trial. Expression discrimination performance was very good on supraliminal trials, and at chance level on subliminal trials. Analogous to the findings of Liddell et al. (2004), an enhanced N2 was triggered by subliminal, but not supraliminal fearful faces, whereas an enhanced parietal P3 component was only observed for supraliminal fearful faces. In addition, this study also revealed a sustained positivity to fearful versus neutral target faces that started 140 ms after target face onset at frontocentral electrodes, analogous to previous results (e.g., Eimer & Holmes, 2002). Importantly, this early emotional positivity was not only present for supraliminal faces, but also, albeit in an attenuated and transient fashion, on subliminal trials. Based on these results, we suggested that the early anterior fear-induced ERP modulations are linked to prefrontal brain processes involved in the rapid detection of emotionally significant sensory signals that are activated even when such signals are insufficient to result in perceptual awareness. However, this interpretation does not necessarily imply that these processes are entirely independent of consciousness. The fact that the early anterior emotional positivity observed in our previous study (Kiss & Eimer, in press) was larger and more sustained for supraliminal relative to subliminal fearful faces might point to the possible existence of a threshold mechanism in the cortical processing of emotional facial expression, with reportable awareness of fearful faces resulting only when the available sensory evidence for the presence of an emotional event is sufficiently strong.

The present experiment investigated this possibility more systematically by studying whether and how early fear-induced ERP responses elicited in the first 300 ms after stimulus onset are related to observers’ reported awareness of the presence of a fearful face. We used a backward-masking procedure where fearful or neutral target faces were immediately followed by a neutral face mask. Fearful masked target faces were chosen because most previous fMRI and ERP studies have contrasted brain responses to fearful and neutral faces to investigate subliminal emotional face processing (see above). Target faces were presented for different durations (short: 17 ms; medium: 50 ms; long: 200 ms), and were thus either clearly visible or difficult to detect. Participants had to indicate on each trial whether or not they saw a masked fearful face. In contrast to previous investigations of emotional face processing (Morris et al., 1998; Whalen et al., 1998; Phillips et al., 2004; Liddell et al., 2004; Kiss & Eimer, in press), where ‘aware’ and ‘unaware’ conditions were defined in terms of fixed target durations, we now used participants’ perceptual reports on single trials to infer the presence versus absence of awareness. To maximize the probability that perceptual reports on single trials would reflect subjective visual awareness rather than random guesses, observers were instructed to only report the presence of a fearful face when they felt reasonably confident. We therefore investigated observers’ subjective thresholds of awareness that reflect their self-reported ability to detect or discriminate critical visual stimuli (see Merikle, Smilek, & Eastwood, 2001). Our aim was to find out whether and how such subjective thresholds are linked to early emotion-specific ERP responses.

Separate averages were computed for trials where masked neutral faces were presented and correctly reported, for trials where a masked fearful face was presented and successfully detected, and for trials where a masked fearful face was presented, but not recognized. Because participants were expected to make correct judgments on virtually all trials where masked faces were presented for 200 ms, only ERPs for correctly detected fearful and neutral faces were computed for this long duration condition. This condition served as a baseline, where ERP differences between trials with masked emotional and neutral faces were expected to resemble the effects observed in previous ERP studies with unmasked faces. Relative to neutral faces, fearful faces presented for 200 ms were expected to trigger an early anterior enhanced positivity and a posterior negativity beyond 200 ms post-stimulus. The important question was whether similar emotional expression effects would also be observed for shorter face durations, and, crucially, whether their presence would be determined by participants’ reported awareness of fearful target faces. To investigate this, ERPs for trials with correctly reported neutral faces were compared to ERPs obtained on trials where a fearful face was correctly detected (fearful-detected trials), and to trials where participants failed to report a fearful face (fearful-undetected trials).

If early ERP modulations triggered by fearful facial expression were determined predominantly by the physical presence of a fearful face, but not by observers’ subjective awareness, ERPs on fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials should be very similar, and should differ systematically from ERPs obtained in response to masked neutral faces. In contrast, if the effects of fearful facial expression on ERP waveforms were more closely linked to brain processes involved in the construction of conscious representations of fearful faces that are accessible to verbal report, early emotional expression effects should be much more pronounced on trials where participants correctly detected the presence of a fearful face, while ERPs on fearful-undetected trials should more closely resemble ERPs for trials with neutral faces.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty-one volunteers were paid to participate in this experiment. Informed consent was obtained prior to testing, and the experiment was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Edinburgh amendments). Two participants were excluded due to their inability to maintain central fixation. Two were excluded because they were unable to discriminate fearful and neutral faces in the long target duration condition. Two others were excluded because they detected more than 90% of all fearful faces in the medium duration condition, leaving an insufficient number of fearful-undetected trials for EEG averaging. Thus, data from 15 participants (10 male) remained in the sample. These participants were all right-handed, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were aged between 19 and 42 years (average age 27.8 years).

Stimuli and procedure

Participants were seated in a dimly lit sound attenuated booth. Stimuli were presented on a 17-inch TFT LCD computer screen (Sony SDM-X72) at a viewing distance of 70 cm. Stimulation parameters were verified by using a photodiode that was placed at the centre of the monitor, and was connected to an EEG amplifier channel with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz, in order to track the response characteristics of the TFT screen on a millisecond-by-millisecond basis. Stimulus onset latencies were determined for target faces presented for 17 ms (without mask) as the point in time when luminance values as measured by the photodiode exceeded the baseline level for an empty screen by more than three standard deviations, and were then compared to analogous values obtained for a CRT monitor (60 Hz refresh rate). Peak intensity levels were also compared. Mean onset latencies differed by only 1.1 ms between TFT and CRT monitors, trial-by-trial onset variability was very small (SDs < 1 ms), and peak intensity levels were almost identical for both types of monitors.

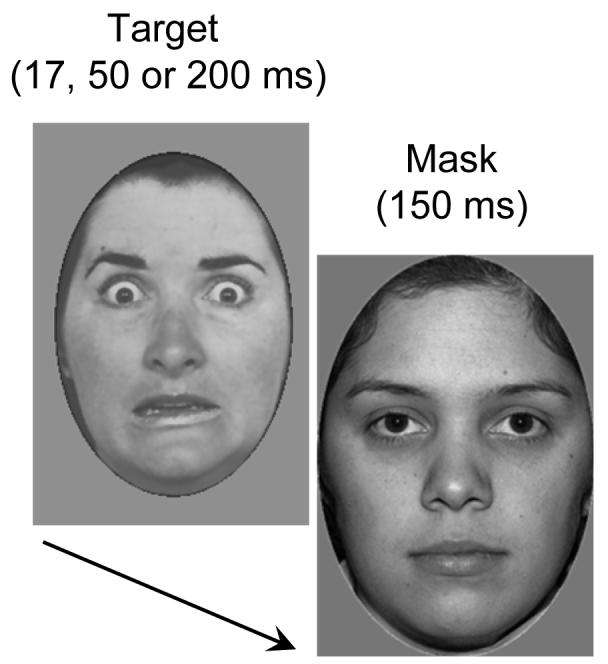

A total of 61 greyscale pictures of faces were used. Faces were presented on a grey background at the centre of the screen. In each trial, a target face was displayed for a variable duration, followed immediately by a face mask, so that stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) was identical to target face duration. Target faces were 40 photographs of 20 different individuals with either neutral or fearful expression taken from a standard set of emotional faces (Ekman & Friesen, 1976). Masking faces were drawn from a different set of 21 neutral faces (NimStim Set of Facial Expressions; http://www.macbrain.org/faces/). All face stimuli were equated for mean luminance in Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA). Target faces subtended 7.4 × 11.4 degrees of visual angle. To improve masking, mask faces were slightly larger (8.2 × 12.9 degrees of visual angle). Target duration was 17, 50 or 200 ms. Mask duration was 150 ms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A typical trial sequence with a fearful face target followed by a slightly larger neutral face mask. Targets were presented for 17, 50, or 200 ms, and were immediately followed by a mask (150 ms duration).

Fearful and neutral target faces were each presented on 50% of all trials, and participants were informed of this fact. They were instructed to press one response button to report that they had seen a masked fearful face, and another response button to report that they did not see a fearful face. To discourage participants from guessing, they were instructed to report fearful target faces only if they felt reasonably confident. Eight participants made a right-hand response to indicate that they had seen a fearful face, and a left response if they did not see a fearful face. For the other seven participants, this response mapping was reversed. The next trial started 1000 ms after a response was registered on the preceding trial. Sixteen blocks were run, and each contained ten randomly intermingled trials for each combination of face expression (fearful vs. neutral) and duration (17 vs. 50 vs. 200 ms), resulting in 60 trials per block.

Data acquisition and analysis

EEG data were DC-recorded (upper cutoff frequency 40 Hz, linked-earlobe reference) and digitized at a sampling rate of 200 Hz using a SynAmps amplifier (Neuroscan). Signals were recorded from 23 electrodes mounted in an elastic cap at scalp sites Fpz, F7, F3, Fz, F4, F8, FC5, FC6, T7, C3, Cz, C4, T8, CP5, CP6, P7, P3, Pz, P4, P8, PO7, PO8, and Oz. Horizontal eye movements were measured from two electrodes placed at the outer canthi of the eyes. All impedances were kept below 5 kΩ.

EEG was epoched offline from 100 ms before to 700 ms after the onset of a masked face. Epochs with activity exceeding ±30 μV in the HEOG channel or ±60 μV in the VEOG channel were excluded from analysis, as were epochs with voltages exceeding ±80 μV at any other electrode. Waveforms were averaged separately for each combination of masked face expression (fearful vs. neutral) and face duration (17 ms vs. 50 ms vs. 200 ms). Trials where neutral target faces were presented were classified as ‘correct’ whenever participants reported the absence of a fearful target face. For the long duration condition, ERPs were computed only for correctly reported fearful and neutral face trials, as error rate was below 10% (SD=4.9%). For the medium and short duration conditions, ERPs to fearful target faces were averaged separately for trials where the presence of a fearful face was reported (fearful-detected trials), for trials where the absence of a fearful face was reported instead (fearful-undetected trials), and for correctly reported neutral face trials. In the short duration condition where participants detected only 21% of all fearful faces, the average number of trials contributing to fearful-detected ERPs was 32. As participants were instructed to report fearful target faces only when reasonably confident, incorrect responses to neutral face targets (i.e., reports of a fearful target face) occurred on less than 10% of these trials (see Table 1), which was not sufficient to compute reliable averaged ERP waveforms for these incorrectly reported neutral face trials.

Table 1.

Fearful face detection performance

| Target duration | % Hits | %False alarms | D-prime |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17 ms | 21.0 | 7.3 | 0.8 |

| 50 ms | 46.9 | 8.7 | 1.5 |

| 200 ms | 91.8 | 8.6 | 2.9 |

Based on the results of earlier ERP studies from our lab with unmasked faces (Eimer & Holmes, 2002; Eimer et al., 2003), mean amplitudes were computed within three successive time windows (130-160 ms, 160-210 ms, and 210-300 ms, relative to target face onset). Separate repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted on mean amplitude values for frontopolar (F7, Fpz, F8), frontal (F3, Fz, F4), and occipito-temporal (PO7, P7, PO8, P8) electrode sites. Statistical analyses were performed separately for each duration condition. For the long duration condition (200 ms), analyses were conducted for the factors emotional expression (correctly reported fearful vs. neutral face) and electrode site (left vs. midline vs. right for frontopolar and frontal electrodes; PO7 vs. P7 vs. PO8 vs. P8 for occipito-temporal electrodes). For the medium and short duration conditions, the factor emotional expression was replaced by the factor trial type (correctly reported neutral face trials vs. fearful-detected trials vs. fearful-undetected trials). Whenever this factor was significant, additional analyses were conducted for pairwise combinations of trial types to identify the source of these differences.

Results

Behavioural results

False alarms (i.e., incorrectly reported fearful faces) occurred on 8.2% of neutral face trials, and false alarm rate did not differ reliably between target durations (see Table 1). As expected, participants’ ability to detect masked fearful faces improved with presentation duration. When masked faces were presented for 200 ms, fearful faces were correctly reported on 91.8% of all trials, relative to 46.9% and 21% for medium and short durations, respectively. To obtain an objective estimate of observers’ ability to detect masked fearful faces, hit and false alarm rates with respect to the presence of a fearful target face were used to calculate a sensitivity measure (d’) for each participant and duration condition (Macmillan & Creelman 1991; see Table 1). Across participants, d’ values were higher for long relative to medium stimulation durations (t(14)=7.5; p<.001), and higher for medium than short durations (t(14)=8.1; p<.001). However, even for the short duration condition, d’ differed significantly from zero (t(14)=5.2; p<.001), indicating that across all participants, detection performance was above chance when masked faces were presented for 17 ms. Response bias c (Macmillan & Creelman, 1991) was computed for all three duration conditions. While c was 0.01 and did not differ from zero in the long duration condition (t<1), participants were more likely to report neutral faces in the medium and short duration conditions (c=1.29 and 0.81, respectively; both t(14)>8.2; both p<.001), due to the fact that they were instructed to report the presence of a fearful face only when reasonably confident (see above).

Response times (RTs) were analysed separately for each duration condition. In the long duration condition, participants were faster to report the presence of a fearful face than its absence (713 vs. 772 ms; t(14)=4.14; p <.001). Mean RT on those few long duration trials where participants missed the presence of a fearful face (837 ms) was slower than RT on trials where the presence or absence of a fearful face was reported correctly (both t(14)>2.6; both p<.02). In the short duration condition, mean RTs for trials with correctly reported neutral faces, fearful-undetected trials, and fearful-detected trials were 690 ms, 717 ms, and 820 ms, respectively, and these differences between trial types were all significant (all t(14)>3.8; all p<.002). In the medium duration condition, mean RTs for correctly reported neutral face trials, fearful-undetected trials, and fearful-detected trials were 710 ms, 776 ms, and 784 ms, respectively. Correct responses to neutral target faces were significantly faster than responses on fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials (both t(14)>2.8; both p<.02), whereas RTs did not differ significantly between fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials.

ERP results

Long duration condition

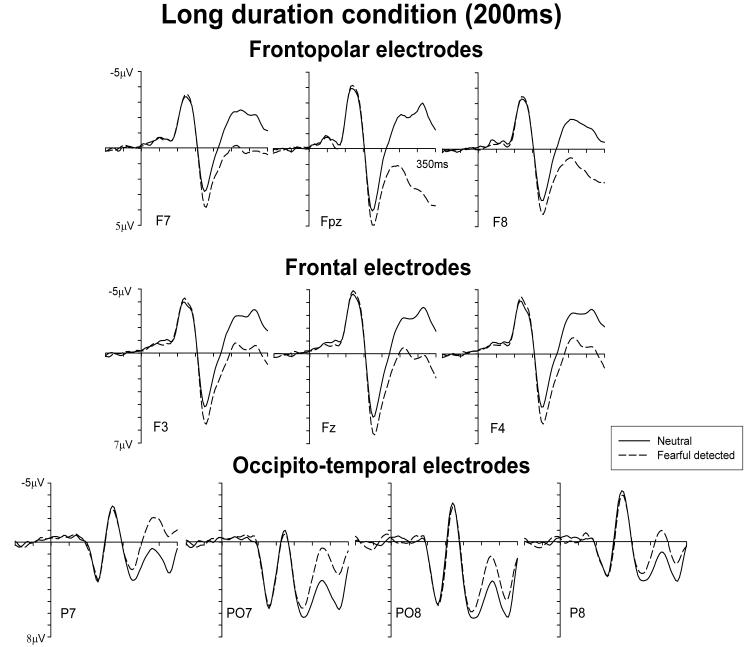

Figure 2 shows ERPs at frontopolar (top), frontal (middle), and occipito-temporal (bottom) electrodes on trials where masked faces were presented for 200 ms, separately for trials where the presence (dashed lines) or absence (solid lines) of a fearful face was correctly reported. As expected, ERP differences between trials with masked fearful and neutral faces were similar to the results observed previously with unmasked faces. An enhanced positivity for fearful relative to neutral faces at frontopolar and frontal electrodes started at about 160 ms post-stimulus, and remained present for the duration of the 350 ms time window shown in Figure 2. In addition, an enhanced negativity for trials with fearful relative to neutral faces started at about 200 ms post-stimulus at lateral occipito-temporal electrodes, again consistent with earlier observations from ERP studies with unmasked faces.

Figure 2.

Grand averaged ERP waveforms elicited by correctly reported masked neutral faces (black solid lines) and detected masked fearful faces (black dashed lines) in the long duration condition (200 ms) at frontopolar, frontal, and occipito-temporal electrodes.

These observations were substantiated by statistical analyses. No significant emotional expression effects were present at frontopolar and frontal sites in the 130-160 ms time window (both F<1). Main effects of emotional expression were obtained in the 160-210 ms window at frontopolar electrodes (F(1,14)=30.0; p<.001) and frontal sites (F(1,14)=38.8; p<.001), reflecting the early phase of the enhanced positivity to masked fearful as compared to neutral faces. This positivity remained present in the subsequent analysis window (210-300 ms post-stimulus), as reflected by main effects of emotional expression at frontopolar (F(1,14)=41.6; p<.001) and frontal electrodes (F(1,14)=28.4; p<.001). At occipito-temporal sites, significant emotional expression effects emerged in the 210-300 ms analysis window (F(1,14)=18.1; p<.001), where ERPs to masked fearful faces were more negative relative to neutral target faces (Figure 2, bottom).

Short duration condition

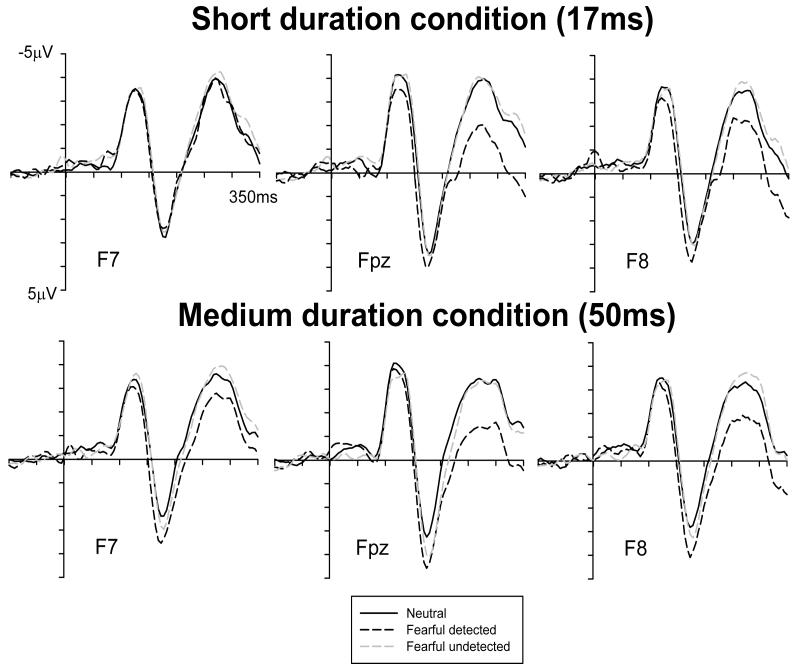

Figures 3 and 4 (top panels) show ERPs at frontopolar and occipito-temporal electrodes in response to masked faces presented for 17 ms, for trials with neutral target faces where participants correctly reported the absence of a fearful face (solid lines), for fearful-detected trials (black dashed lines), and fearful-undetected trials (grey dashed lines). Relative to neutral face trials, ERPs on fearful-detected trials show a frontopolar positivity and an enhanced negativity at occipito-temporal electrodes, similar to the effects found in the long duration condition. In contrast, these emotional expression effects seem entirely absent on fearful-undetected trials.

Figure 3.

Grand averaged ERP waveforms elicited at frontopolar electrodes in the short duration condition (17 ms, top) and the medium duration condition (50 ms, bottom) in response to correctly reported masked neutral faces (black solid lines), detected fearful faces (black dashed lines), and undetected fearful faces (grey dashed lines).

Figure 4.

Grand averaged ERP waveforms elicited at lateral occipito-temporal electrodes in the short duration condition (17 ms, top) and the medium duration condition (50 ms, bottom) in response to correctly reported masked neutral faces (black solid lines), detected fearful faces (black dashed lines), and undetected fearful faces (grey dashed lines).

In the 130-160 ms analysis window, a main effect of trial type was present at frontopolar sites (F(2,28)=5.2; p<.03; ε=.636), and was accompanied by a trial type x electrode site interaction (F(4,56)=3.3; p<.05; ε=.524). As shown in Figure 3 (top), ERPs to detected fearful faces were more positive than ERPs to undetected fearful or neutral faces at midline electrode Fpz and at F8 (right hemisphere), but not at left frontopolar electrode F7. Follow-up analyses were conducted separately for pairwise combinations of trial types (with trial type now a two-level factor). A significant effect of trial type was obtained when ERPs on fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials were analysed together (F(1,14)=7.3; p<.02). This effect was almost significant when ERPs on fearful-detected and neutral face trials were analysed together (F(1,14)=4.1; p<.06), whereas no such differences were found between ERPs for fearful-undetected and neutral face trials (F<1.4). When these analyses were restricted to Fpz and right-hemisphere electrode F8, where systematic emotional expression effects were present (Figure 3, top), significant trial type effects were obtained when ERPs on fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials were analysed together (F(1,14)=12.1; p<.005), and when ERPs on fearful-detected and neutral face trials were analysed together (F(1,14)=6.3; p<.03), but not for the combination of fearful-undetected and neutral face trials (F<1.3). Overall, these results demonstrate an early frontopolar emotional positivity when the presence of a fearful target face was correctly reported that was absent when participants failed to detect a fearful face. A similar pattern of results was also observed at frontal sites (not shown in Figure 3). However, the main effect of trial type failed to reach overall statistical significance here (F(2,28)=3.8; p<.07; ε=.595).

No significant effect of trial type was obtained in the 130-160 ms post-stimulus window at occipito-temporal electrodes (F<1), and in the subsequent 160-210 ms interval at frontopolar, frontal, or occipito-temporal sites (all F<1.8). However, effects of trial type emerged again at frontopolar and occipito-temporal (but not at frontal) sites between 210 and 300 ms post-stimulus. At frontopolar electrodes, a main effect of trial type (F(2,28)=5.9; p<.02; ε=.632) was accompanied by a trial type x electrode site interaction (F(4,56)=6.8; p<.005; ε=.601). As can be seen in Figure 3 (top), ERPs to detected fearful faces were more positive than ERPs to undetected fearful or neutral faces at midline electrode Fpz and over the right hemisphere (F8), but not at left frontopolar electrode F7. Again, follow-up analyses were conducted for combinations of two trial types. Significant trial type effects were obtained when ERPs to detected and undetected fearful faces were analysed together (F(1,14)=6.9; p<.02), and when ERPs to detected fearful and to neutral faces were combined (F(1,14)=6.0; p<.03), but no differences were found between ERPs to undetected fearful and neutral faces (F<1). At occipito-temporal sites, a main effect of trial type (F(2,28)=6.0; p<.02; ε=.633) indicated that ERPs to detected fearful faces were more negative than ERPs to undetected fearful and neutral faces (see Figure 4, top panel). This was confirmed by analyses for combinations of two trial types, which revealed significant trial type effects when ERPs to detected and undetected fearful faces (F(1,14)=4.8; p<.05) and ERPs to detected fearful and neutral faces were combined (F(1,14)=8.5; p<.02).

In summary, systematic emotional expression effects were observed for correctly reported fearful faces in the short duration condition between 130 and 160 ms (at frontopolar sites) and between 210 and 300 ms post-stimulus (at frontopolar and occipito-temporal electrodes). In contrast, ERPs on fearful-undetected trials were statistically indistinguishable from ERPs to masked neutral faces.

Medium duration condition

Figures 3 and 4 (bottom panels) show ERPs to masked faces presented for 50 ms at frontopolar and occipito-temporal electrodes, separately for trials where a masked neutral face was presented and correctly reported (solid lines), fearful-detected trials (black dashed lines), and fearful-undetected trials (grey dashed lines). Similar to the short duration condition, a frontal positivity and an occipito-temporal negativity was triggered to detected fearful faces relative to trials with neutral faces. ERPs for fearful-undetected trials appear similar to ERPs to neutral faces at frontopolar electrodes, but intermediate between ERPs for fearful-detected and neutral face trials at occipito-temporal sites.

In the 130-160 ms time window, a main effect of trial type (neutral, fearful-detected, fearful-undetected) was present at frontopolar electrodes (F(2,28)=7.6; p<.02; ε=.976). As for the short duration condition, ERPs on fearful-detected trials were more positive than ERPs on fearful-undetected or neutral face trials. In Figure 3 (bottom panel), this difference is visible on the descending flank of the N1 component. Follow-up analyses for pairwise combinations of two trial types revealed significant trial type effects when ERPs on fearful-detected and neutral face trials were analysed together (F(1,14)=7.9; p<.02), and when ERPs on fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials were combined (F(1,14)=16.2; p<.001). In contrast, no reliable differences were found between ERPs to fearful-undetected and neutral face trials (F<1), indicating that an early emotional positivity was elicited only when observers correctly reported the presence of a fearful target face.

In the 160-210 ms measurement window, main effects of trial type were again present at frontopolar electrodes (F(2,28)=13.3; p<.001; ε=.989). Here, analyses for pairwise combinations of two trial types revealed significant trial type effects not only for the combination of fearful-detected and neutral face trials (F(1,14)=28.0; p<.001) and the combination of fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials (F(1,14)=5.8; p<.04), but also for the combination of fearful-undetected and neutral face trials (F(1,14)=7.4; p<.02). This demonstrates that there were reliable differences between all three trial types at frontopolar sites, with ERPs to detected fearful faces more positive than ERPs to undetected fearful faces, and ERPs to undetected fearful faces more positive that ERPs to neutral faces (see Figure 3, bottom). In other words, presenting a masked fearful face for 50 ms resulted in an attenuated, but still reliable frontopolar positivity in the 160-210 ms time window when participants failed to report its presence. A similar pattern was found at frontal electrodes (not shown in Figure 3), where a main effect of trial type was also present (F(2,28)=6.3; p<.01; ε=.990). Follow-up analyses for pairwise combinations of trials types revealed reliable trial type effects when ERPs to detected fearful and neutral faces were analysed together (F(1,14)=11.1; p<.001) and for ERPs to undetected fearful versus neutral faces (F(1,14)=6.6; p<.03). However, there were no significant differences between ERPs to detected and undetected fearful faces (F<1.1). No significant effects of trial type were observed in the 160-210 ms interval at occipito-temporal electrodes (F<1.7).

In the 210-300 ms measurement interval, a main effect of trial type was again present at frontopolar electrodes (F(2,28)=14.5; p<.001; ε=.981). Follow-up analyses for pairwise combinations of trial types revealed systematic differences between ERPs on fearful-detected trials and ERPs on neutral and fearful-undetected trials, respectively (main effects of trial type: F(1,14)=21.1 and 20.1, respectively; both p<.001), but no difference (F<1) between ERPs to fearful-undetected and neutral face trials (see Figure 3, bottom panel). At frontal electrodes (not shown in Figure 3), the main effect of trial type narrowly failed to reach statistical significance (F(2,28)=3.3; p<.06; ε=.987). At occipito-temporal electrodes, a main effect of trial type was present during the 210-300 ms analysis window, (F(2,28)=5.2; p<.02; ε=.856). Figure 4 (bottom panel) indicates that ERPs were most negative in response to detected fearful faces, and more negative for undetected fearful than for neutral faces. To evaluate these differences, follow-up analyses were again conducted for pairwise combinations of trial types. When ERPs in response to detected fearful faces and neutral faces were analysed together, an effect of trial type (F(1,14)=10.3; p<.01) was obtained, reflecting the occipito-temporal negativity for fearful relative to neutral faces that was also present in the other duration conditions. A significant trial type effect also emerged when ERPs to fearful-undetected and neutral faces were analysed together (F(1,14)=5.0; p<.05), whereas no such effect was present for ERPs on fearful-detected versus fearful-undetected trials (F<1.6), indicating that although there was a trend for an enhanced occipito-temporal negativity for trials with detected relative to undetected fearful faces (see Figure 4, bottom), this difference was not reliable.

Discussion

To investigate links between subjective thresholds of conscious awareness, as reflected by observers’ perceptual reports, and rapid ERP responses to fearful faces, a backward masking paradigm was employed where masked fearful or neutral target faces were presented for 17, 50, or 200 ms. For the long target duration condition, effects of emotional expression on ERP waveforms closely resembled findings from previous ERP studies for unmasked emotional faces (cf., Ashley et al., 2004; Eimer & Holmes, 2002; Eimer et al., 2003; Holmes et al., 2003; Marinkovic & Halgren, 1998), with an early enhanced positivity to fearful faces at frontopolar and frontal electrodes, and an enhanced negativity for fearful faces at occipito-temporal electrodes. It should be noted that solid emotional expression effects were obtained in the long duration condition in spite of the fact that individual fearful and neutral target faces were presented repeatedly across 16 experimental blocks, thereby suggesting that these ERP effects are not subject to rapid habituation.

Having confirmed that rapid emotional expression effects were reliably elicited in the long duration condition, the critical question was whether these ERP effects are triggered by fearful faces regardless of whether participants are able to report them, or whether they are more closely associated with subjective perceptual awareness. If early ERP modulations sensitive to emotional facial expression were triggered by the presence of a fearful face independently of subjective awareness, they should be present on fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials. If these effects were more closely associated with observers’ subjective awareness, fear-induced ERP modulations should be restricted to fearful-detected trials, while ERPs on fearful-undetected trials should be similar to ERPs for trials with neutral target faces.

In the short duration condition, emotion discrimination performance was above chance (see Pessoa, Japee, & Ungerleider, 2005, for similar findings). The ERP results observed in this condition suggest that early ERP effects of fearful facial expression are closely associated with subjective awareness. While ERPs on fearful-undetected trials were statistically indistinguishable from ERPs in response to masked neutral faces, emotional expression effects were present on those trials where participants correctly reported fearful target faces. The fact that fear-induced early ERP modulations were triggered exclusively on fearful-detected trials, but not when participants failed to report fearful faces, suggests close links between rapid ERP responses to fearful faces and their availability to conscious awareness. In the medium duration condition, an early frontopolar emotional positivity in the 130-160 ms time window and a later positivity between 210 and 300 ms was found only on fearful-detected trials, but not for fearful-undetected trials, thus again suggesting close links between these early anterior emotional expression effects and reportable conscious awareness. However, there was also some evidence for fear-specific ERP modulations in response to undetected fearful faces that were triggered beyond 200 ms at lateral occipito-temporal sites (Figure 4, bottom panel), and during the 160-210 ms latency window at frontopolar sites, where fearful-undetected ERPs differed reliably from ERPs for neutral face trials.

In summary, while early emotional expression effects were closely linked with reportable conscious awareness in the short duration condition, this link was less apparent in the medium duration condition where attenuated but significant emotional expression effects were also triggered in response to undetected fearful faces. The presence of emotional expression effects on fearful-undetected trials in the medium duration condition is likely to be linked to the fact that participants were encouraged to adopt a conservative response criterion when reporting fearful faces. It is possible that on at least some trials where masked fearful faces were presented for 50 ms, some sensory evidence for the presence of a fearful face was in fact available, but remained below a conservative threshold for report. This interpretation is also in line with the fact that participants were slower to report the absence of a fearful face on trials where a fearful face was in fact present than on trials with neutral target faces. The hypothesis that the gradual ERP differences between fearful-detected, fearful-undetected, and neutral trials observed in the medium duration condition reflect gradual differences in the amount of sensory evidence for the presence of a fearful face that is accessible for report should be evaluated in future studies where response criteria are systematically manipulated.

An unexpected finding was that emotional expression effects were absent at left frontopolar site F7 in the short duration condition, while such effects were clearly present at this electrode in the medium and long duration conditions (see Figures 2 and 3). If replicated in future experiments, this difference could point to a right-hemisphere dominance in the rapid detection of emotional information presented close to detection threshold, which would be consistent with fMRI data revealing a right amygdala bias for the processing of transient emotional face stimuli (Morris et al., 1998, 1999).

The finding that the earliest expression-sensitive ERP modulations that are triggered over anterior brain regions within the first 150 ms after stimulus onset are closely linked to observers’ reported awareness is consistent with results from previous ERP experiments demonstrating that emotion-specific ERP effects are modulated by attention (Eimer et al., 2003; Holmes et al., 2003), and with fMRI results by Pessoa, Japee, Sturman, & Ungerleider (2006), who demonstrated that fear-specific amygdala activations were modulated by observers’ reported subjective awareness. Stronger amygdala responses were found on trials where observers reported a fearful face than on trials where they failed to report it, suggesting that fear-specific amygdala activation may be closely linked to the visibility of masked fearful faces.

It should be noted that the current results are only partially consistent with the findings from our previous study (Kiss & Eimer, in press), where early anterior fear-induced ERP modulations were observed (albeit in a transient and attenuated fashion) on subliminal trials where masked faces were presented for only 8 ms and discrimination performance was at chance level. While this result suggests that early emotional expression effects are at least to some degree triggered by the physical presence of fearful faces, and independently of observers’ awareness of these faces, the findings from the short duration condition of the present experiment indicated close links between these early ERP effects and awareness. This apparent discrepancy between these two experiments might at least in part be due to the differences in the way that ERPs for different trial types were computed. In the present study, EEG was averaged separately for fearful-detected and fearful-undetected trials in the short duration condition. Given that focal attention is known to be required for the processing of near-threshold emotional stimuli (Pessoa & Ungerleider, 2004), those few trials where participants successfully detected the presence of masked fearful faces presented for only 17 ms are likely to be trials where attentional resources were fully focussed on the emotion task, whereas attention will have been less focussed on fearful-undetected trials. In contrast, ERPs to masked fearful faces were not averaged separately as a function of detection performance in our previous experiment (Kiss & Eimer, in press). Thus, these ERPs will have included a mixture of trials where attention was either focussed or diffuse, which leaves open the possibility that the small and transient ERP emotional expression effects observed for subliminal trials were generated only on those trials where attention was fully focussed.

A similar argument may also account for the observation that frontopolar emotional expression effects were already reliably present during the 130-160 ms post-stimulus measurement window for fearful-detected trials in the short and medium duration conditions, whereas they only emerged in the 160-210 ms interval in the long duration condition. If the detection of masked fearful faces depends critically on focal attention when faces are presented briefly, fearful-detected trials in the two shorter duration conditions will represent trials where attentional resources were fully focussed. If focal attention is less relevant when masked target faces are clearly visible, fearful faces in the long duration condition are likely to be detected even when attention is incompletely focussed. In other words, differences in the onset latency of emotional expression effects might reflect a stronger contribution of fully focussed attention to ERPs on fearful-detected trials for conditions where fearful faces are harder to detect. Future studies will need to investigate these relationships between emotion-specific ERP responses to masked faces and focal attention in more detail, not only for fearful faces but also for other emotional facial expressions.

Overall, the present study has demonstrated that rapid ERP responses triggered by masked fearful faces within 150 ms or less after stimulus onset are closely associated with observers’ reportable awareness, although some of these response may also be triggered, albeit in an attenuated fashion, in response to fearful faces that remain undetected (see also Kiss & Eimer, in press). While detailed hypotheses about the neural basis of the emotional expression effects observed in the present and previous ERP studies would be premature, it is possible that the anterior positivity triggered by fearful faces within 150 ms or less after stimulus onset is generated in prefrontal, orbitofrontal, or anterior cingulate cortex by neural mechanisms involved in the rapid detection of facial expression. In this context, it is interesting to note that the dorsal subdivision of the anterior cingulate has previously been suggested as a potential locus of emotional awareness (Lane et al., 1998). The posterior negativity in response to fearful faces might reflect the selective attentional processing of fearful faces in extrastriate visual areas, which could be triggered by fear-specific control signals from sustained amygdala activation (Sato et al., 2001), and result in perceptual awareness of emotional stimuli. The observation that anterior and posterior early emotional expression effects were closely linked to participants’ reported awareness of a fearful face suggests that the underlying emotion-specific brain processes are directly involved in the construction of conscious representations of emotional facial expression.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by a grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), UK. M.E. holds a Royal Society-Wolfson Research Merit Award.

References

- Adolphs R. Neural systems for recognizing emotion. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2002;12:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphs R. Cognitive neuroscience of human social behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:165–178. doi: 10.1038/nrn1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison T, Puce A, McCarthy G. Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4:267–278. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley V, Vuilleumier P, Swick D. Time course and specificity of event-related potentials to emotional expressions. Neuroreport. 2004;15:211–216. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200401190-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan R. Emotion, cognition, and behavior. Science. 2002;298:1191–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1076358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimer M, Holmes A. An ERP study on the time course of emotional face processing. Neuroreport. 2002;13:427–431. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200203250-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimer M, Holmes A, McGlone FP. The role of spatial attention in the processing of facial expression: An ERP study of rapid brain responses to six basic emotions. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;3:97–110. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen W. Pictures of facial affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Etcoff NL. Selective attention to facial identity and facial emotion. Neuropsychologia. 1984;22:281–295. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(84)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI. The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4:223–233. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman EA, Haxby JV. Distinct representations of eye gaze and identity in the distributed human neural system for face perception. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:80–84. doi: 10.1038/71152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Vuilleumier P, Eimer M. The processing of emotional facial expression is gated by spatial attention: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Cognitive Brain Research. 2003;16:174–184. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6410(02)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak J, Rolls ET, Wade D. Face and voice expression identification in patients with emotional and behavioural changes following ventral frontal lobe damage. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:247–261. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Kaufman O, Damasio H, Damasio AR, Granner M, Bakken H, Hori T, Howard MA, 3rd, Adolphs R. Single-neuron responses to emotional visual stimuli recorded in human ventral prefrontal cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4:15–16. doi: 10.1038/82850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss M, Eimer M. ERPs reveal subliminal processing of fearful faces. Psychophysiology. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00634.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krolak-Salmon P, Henaff MA, Vighetto A, Bertrand O, Mauguiere F. Early amygdala reaction to fear spreading in occipital, temporal, and frontal cortex: a depth electrode ERP study in human. Neuron. 2004;42:665–676. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane RD, Reiman EM, Axelrod B, Yun LS, Holmes A, Schwartz GE. Neural correlates of levels of emotional awareness: Evidence of an interaction between emotion and attention in the anterior cingulate cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10:525–535. doi: 10.1162/089892998562924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell BJ, Williams LM, Rathjen J, Shevrin H, Gordon E. A temporal dissociation of subliminal versus supraliminal fear perception: An event-related potential study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2004;16:479–486. doi: 10.1162/089892904322926809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Ioannides AA, Streit M. Single trial analysis of neurophysiological correlates of the recognition of complex objects and facial expressions of emotion. Brain Topography. 1999;11:291–303. doi: 10.1023/a:1022258620435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection theory: A user’s guide. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Marinkovic K, Halgren E. Human brain potentials related to the emotional expression, repetition, and gender of faces. Psychobiology. 1998;26:348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Merikle PM, Smilek D, Eastwood JD. Perception without awareness: perspectives from cognitive psychology. Cognition. 2001;79:115–134. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Öhman A, Dolan RJ. Conscious and unconscious emotional learning in the human amygdala. Nature. 1998;393:467–470. doi: 10.1038/30976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS, Öhman A, Dolan RJ. A subcortical pathway to the right amygdala mediating “unseen” fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1999;96:1680–1685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasley BN, Mayes LC, Schultz RT. Subcortical discrimination of unperceived objects during binocular rivalry. Neuron. 2004;42:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L. To what extent are emotional visual stimuli processed without attention and awareness? Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2005;15:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Japee S, Sturman D, Ungerleider LG. Target visibility and visual awareness modulate amygdala responses to fearful faces. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16:366–375. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Japee S, Ungerleider LG. Visual awareness and the detection of fearful faces. Emotion. 2005;5:243–247. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, Ungerleider LG. Neuroimaging studies of attention and the processing of emotion-laden stimuli. Progress in Brain Research. 2004;144:171–182. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)14412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Williams LM, Heining M, Herba CM, Russell T, Andrew C, Bullmore ET, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Morgan M, et al. Differential neural responses to overt and covert presentations of facial expressions of fear and disgust. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1484–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posamentier MT, Abdi H. Processing faces and facial expressions. Neuropsychology Review. 2003;13:113–143. doi: 10.1023/a:1025519712569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato W, Kochiyama T, Yoshikawa S, Matsumura M. Emotional expression boosts early visual processing of the face: ERP recording and its decomposition by independent component analysis. Neuroreport. 2001;12:709–714. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103260-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutter DJLG, de Haan EHF, Van Honk J. Extending the global workspace theory to emotion: Phenomenality without access. Consciousness and Cognition. 2004;13:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutter DJLG, Van Honk J. Functionally dissociated aspects in anterior and posterior electrocortical processing of facial threat. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2004;53:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderploeg RD, Brown WS, Marsh JT. Judgments of emotion in words and faces: ERP correlates. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 1987;5:193–205. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(87)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier P, Armony JL, Clarke K, Husain M, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Neural response to emotional faces with and without awareness: Event-related fMRI in a parietal patient with visual extinction and spatial neglect. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:2156–2166. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen PJ, Rauch SL, Etcoff NL, McInerney SC, Lee MB, Jenike MA. Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:411–418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00411.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM, Liddell BJ, Rathjen J, Brown KJ, Gray J, Phillips M, Young A, Gordin E. Mapping the time course of nonconscious and conscious perception of fear: An integration of central and peripheral measures. Human Brain Mapping. 2004;21:64–74. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MA, Morris AP, McGlone F, Abbott DF, Mattingley JB. Amygdala responses to fearful and happy facial expressions under conditions of binocular suppression. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:2898–2904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4977-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AW, Newcombe F, de Haan EH, Small M, Hay DC. Face perception after brain injury. Selective impairments affecting identity and expression. Brain. 1993;116:941–959. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.4.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]