Abstract

MIP-2 and IFN-γ inducible protein-10 (IP-10) and their respective receptors, CXCR2 and CXCR3, modulate tissue inflammation by recruiting neutrophils or T cells from the spleen or bone marrow. Yet, how these chemokines modulate diseases such as immune-mediated drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is essentially unknown. To investigate how chemokines modulate experimental DILI in our model we used susceptible BALB/c (WT) and IL-4−/− (KO) mice that develop significantly reduced hepatitis and splenic T cell priming to anesthetic haptens and self proteins following TFA-S100 immunizations. We detected CXCR2+ splenic granulocytes in all mice two weeks following immunizations; by 3 weeks, MIP-2 levels (p<0.001) and GR1+ cells were elevated in WT livers, suggesting MIP-2-recruited granulocytes. Elevated splenic CXCR3+ CD4+T cells were identified after 2 weeks in KO mice indicating elevated IP-10 levels which were confirmed during T cell priming. This result suggested that IP-10 reduced T cell priming to critical DILI antigens. Increased T cell proliferation following co-culture of TFA-S100-primed WT splenocytes with anti-IP-10 (p<0.05) confirmed that IP-10 reduced T cell priming to CYP2E1 and TFA. We propose that MIP-2 promotes and IP-10 protects against the development of hepatitis and T cell priming in this murine model.

Keywords: CYP2E1, trifluoroacetyl chloride, TFA, DILI, MIP-2, IP-10, KC chemokines

Introduction

Drugs such as halogenated volatile anesthetics, antibiotics, tienilic acid, dihydrazaline, carbamazepine, and alcohol can induce immune-mediated drug-induced liver injury (DILI) in susceptible individuals [1]. Previous investigations suggest that halogenated volatile anesthetic-induced DILI from isoflurane, desflurane or halothane is triggered by neoantigens formed from native hepatic proteins such as cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) [2,3] that have been covalently modified by the trifluroacetyl chloride (TFA) hapten formed by CYP2E1 oxidative metabolism of the anesthetic [4–6]. These neoantigens then induce immune responses characterized by hepatitis as well as antibodies to self proteins or drug haptens. We have tested this hypothesis by developing a murine model of the initiation of anesthetic DILI induced by immunizing BALB/c mice with trifluoroacetylated S100 liver proteins (TFA-S100) [7].

In our model, experimental DILI initially develops 3 weeks following TFA-S100 immunization. It consists primarily of neutrophils, similar to acetaminophen or alcohol hepatitis [8–11], as well as eosinophils, documented in patients with drug-induced hepatitis [12] and in mice with Con A-induced hepatitis [13]. Cultured splenocyte supernatant analyzed 2 weeks after TFA-S100 immunizations, but prior to the appearance of substantial hepatitis, reveals significantly elevated pro-inflammatory and regulatory cytokines, suggesting that systemic immune activation precedes hepatic inflammation [7]. Interestingly, in infectious hepatitis in humans or in animal models of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), pro-inflammatory and regulatory cytokines can be both destructive [10,14–16] or protective [10,17,18] and roles for chemokines in these processes remain unclear. Recruitment of neutrophils or mononuclear cells to the sites of infection or tissue injury can be modulated by local production of chemokines and their receptors. Subsequently, chemokines attract cells expressing the complementary receptor to these tissue sites. Landmark studies have clearly demonstrated roles for both macrophage inflammatory protiein-2 (MIP-2) and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) in the recruitment of CXCR2+ neutrophils following surgical injury [19,20] as well as in infectious disease models [21,22]. Studies investigating the IFN-γ-dependent chemokines, IFN-γ inducible protein-10 (IP-10) and mouse monokine induced by interferon gamma (MIG) also demonstrate critical roles for these chemokines in the recruitment of CXCR3+ T cells during the development of infectious and autoimmune diseases [23,24]. However, roles for IP-10 and MIP-2 in the priming of T cells to newly formed neoantigens or their roles in the development of DILI are as yet unknown.

IP-10 and MIG have been shown to worsen hepatic inflammation in infectious hepatitis, AIH [23,24] and hepatitis following toxic doses of acetaminophen [25]. Hence, these chemokines have been suggested as targets for therapeutic agents aimed at blocking these pathogenic conditions. However, an earlier study suggested that IP-10 may have a protective role in acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity [26]. Thus, it is possible that IP-10 may have dual roles wherein hepatitis worsens when IP-10 binds to the CXCR3 chemokine receptor and promotes Th1-mediated inflammation. Yet, IP-10 can also bind to the CCR3 chemokine receptor expressed on mast cells and Th2 cells [27], which would inhibit chemotaxis of these cells and thus potentially decrease Th2-mediated inflammation.

We have investigated how chemokines MIP-2, IP-10 and their respective receptors modulate hepatic inflammation and T cell priming in the development of experimental DILI utilizing susceptible BALB/c (WT) and significantly less susceptible IL-4 deficient (KO) mice.. We have discovered that both MIP-2 and IP-10 play significant roles in the development of anesthetic DILI. Critical immune reactions regulated by IP-10 during T cell priming and MIP-2 during the development of hepatitis suggest both protective and pathologic roles for these chemokines.

Methods

Mice

Eight to 10 week-old, female, inbred BALB/c (WT) and IL-4 −/− (KO) mice, were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) and were maintained under pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Approval for all procedures was obtained from the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University.

Induction of hepatitis with TFA haptenated cytosolic S-100 (TFA-S100)

Hepatitis was induced in WT or KO mice by s.c. immunization with 200 μg of syngenic TFA-S100, emulsified in an equal volume of CFA (Difco Bacto Adjuvant Complete Freund H37 Ra) as previously described [7]. The mice were killed two or three weeks after the initial immunization. Experiments were run in duplicate with N = 10 mice per group.

Analysis of tissue sections

Liver tissue sections (0.5 μm thick) were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, stained with H&E and then scored for inflammation and injury using the following grading system adapted from Howell and Yoder [28]: Grade 0, no portal tract, lobular inflammation or hepatocyte necrosis; Grade 1, minor periportal or lobular inflammation without necrosis; Grade 2, periportal or lobular inflammation involving < 50% of the liver section; Grade 3, periportal or lobular inflammation involving ≥ 50% of the liver section or inflammation with necrosis; Grade 4, inflammation with bridging necrosis.

Analysis of TFA-S100 – Primed Splenocytes

Splenocytes were obtained two weeks following this initial TFA-S100 immunization. 2.5 × 105/100μl of the cells were added to each well of the 96 well plates ± anti-murine IP-10 (0.9 μg/ml, affinity purified polyclonal antibody, from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ)) and incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% air (humidified). Twelve to 18h prior to the 24h time point the cells were pulsed with 10 μl 3H, 1 μCi/well. Splenocyte supernatants were isolated from plates were loaded with 100 μl of cells as above in medium ± CYP2E1 (Gentest, BD Biosciences, Woburn, MA) or trifluoroacetylated keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH-TFA), 10 μg/ml. The plates were incubated for 72 hours. All experiments were performed in duplicate with 4 mice/group.

FACS analysis for cell type and chemokine receptors in TFA-S100 – primed splenocytes

Hepatic infiltrating immune cells were isolated from WT mice [7]. Splenocytes from WT and KO mice were also isolated. All cells were pooled by treatment and strain. Infiltrating immune cells from livers of CFA ± TFA-S100 – immunized WT mice were stained with 1:100 dilutions of the following FITC/PE/CyChrome™ or APC-labeled antibody combinations: CD4 (L3T4, clone H129.19)/CD8a (Ly-2, clone 53.7.7)/CD3e (clone 145-2C11); CD11c (clone HL3)/CD8a (Ly-2, clone 53.7.7)/CD3e (clone 145-2C11) and F4/80 (clone BM8)/Ly-6G Gr-1(clone RB6-8C5)/CD45 (clone 30-F11). All antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) except F4/80 which was obtained from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). The cells were fixed with PBS/4%paraformaldeyde and analyzed by flow cytometry within three days. Experiments were done in duplicate with 4 – 5 mice per group.

For chemokine receptor surface staining, spleen cells form above naïve and TFA-S100 –immunized WT and KO mice were stained with 1:100 dilutions of the following FITC/PE/Cy5™ antibody combinations: CD45R B220 (clone RA3-6B2)/CXCR3 (clone 220803)/no Cy5; CD8a (Ly-2, clone 53.7.7)/CXCR3 (clone 230803)/CD4 (L3T4, clone H129.19) and GR-1/CXCR2 (clone 242216). All antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). The cells were fixed with PBS/4%paraformaldeyde and analyzed by flow cytometry within three days.

Chemokine measurements

Chemokines levels in liver and spleen samples from individual mice were measured in supernatants from tissue homogenates (10% weight/volume in 2% MEM) using Quantikine cytokine ELISA kits purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), according to manufacturer’s instructions and were standardized by converting chemokine levels to pg/g of tissue, as previously described [7]. Chemokines were also measured in splenocyte culture supernatants collected and stored at −80°C until used and were expressed as pg/mL.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad® Prism Version 3.02 for Windows (GraphPad® Software, Incorporated, San Diego, CA). Histology scores were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U. Cellular composition and chemokines were analyzed by ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Results

The hepatic inflammatory infiltrate in experimental anesthetic DILI primarily consists of neutrophils

Female BALB/c (WT) mice immunized on days 0 and 7 with 200μg of TFA-S100 emulsified in CFA as well as injection with 500ng pertussis toxin on days 0 [7] demonstrated significant hepatitis by 3 – 4 weeks (Figure 1A). Prior to determining the role of chemokines in the development of hepatitis we wanted to confirm the presence of abundant neutrophils previously documented only by immunohistochemical analysis [7]. Characterization of the hepatic infiltrate in WT mice helped to identify potential chemokines that signal the accumulation these cells following immunization with TFA-S100.

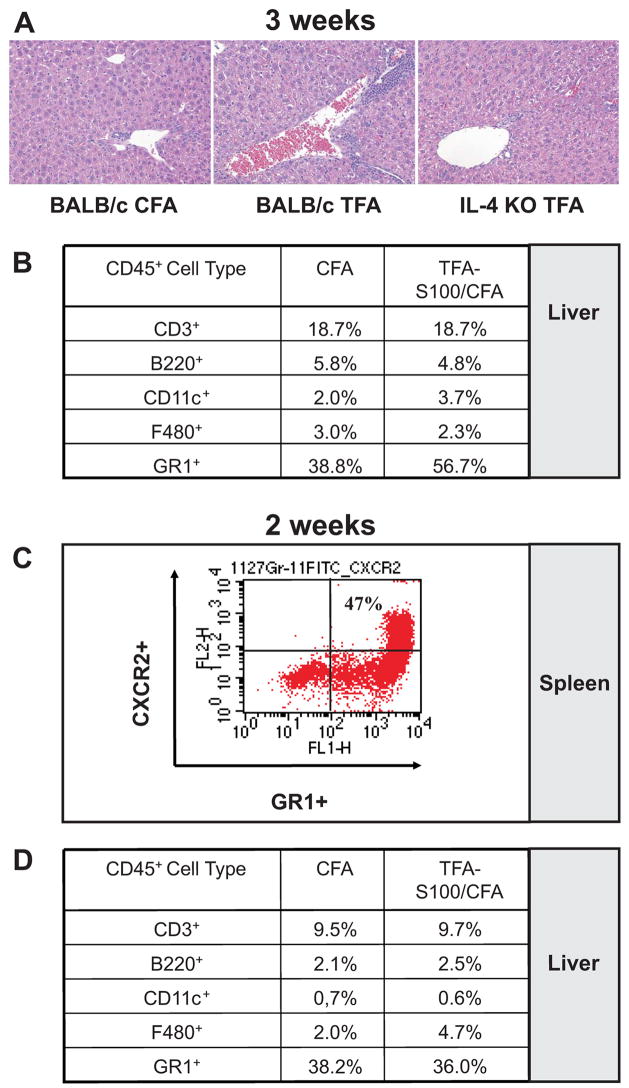

Figure 1. TFA-S100 - induced hepatitis in mice is preceded by CXCR2 expression on splenic granulocytes.

(A) Representative H & E histological sections from WT and KO mice (0.5 microns thick) three weeks following initial CFA/TFA-S100 immunizations demonstrated significantly more hepatitis in WT when compared to KO mice (64 X magnifications). (B) While the expression of CD3+, B220+, CD11c+ or F480+ cells in WT livers was not different in livers from CFA and CFA/TFA-S100 – immunized WT mice, CD45+ GR-1+ neutrophils were markedly elevated in livers from TFA-S100-immunized WT mice 3 weeks following immunization. (C) Approximately one half of the splenic GR1+ granulocytes from TFA-S100 –immunized WT mice expressed CXCR2 prior to the development of significant hepatitis. (D) Expression of GR1+ granulocytes in the liver was not significantly different between CFA and CFA/TFA-S100 – immunized WT mice 2 weeks after immunizations. All experiments were run in duplicate (N = 4 – 5 mice/group).

Using FACS analysis, we found markedly elevated CD45+ GR-1+ cells which could represent neutrophils, in livers of TFA-S100-immunized WT mice after 3 weeks when compared to control mice immunized with CFA alone (Figures 1A). This result confirmed that granulocytes were recruited to the liver following TFA-S100 immunizations. Levels of CD3+, B220+, CD11c+ and F480+ in the hepatic infiltrate were similar in TFA-S100 – immunized or control WT mice. Next, we hypothesized that demonstrating granulocytes in the spleen prior to the development of significantly elevated hepatitis suggested that these cells generated in the spleen or in other secondary lymphoid organs could subsequently be recruited to the liver by expression of neutrophil chemoattractants. Hence, two weeks following immunizations, we stained for CD45+GR1+ cells in the spleen and measured expression of the neutrophil chemoattractant receptor, CXCR2 on GR1+ cells. To confirm the absence of significant hepatitis at the two week time point, we also analyzed infiltrating cells from the liver.

Approximately one half of the splenic granulocytes expressed the neutrophil chemoattractant receptor CXCR2 (Figure 1C); however, the expression of CXCR2+ GR1+ granulocytes was not significantly different between TFA-S100 – immunized and control mice. We further confirmed the absence of significant differences in GR1+ cells in the hepatic infiltrate at the two week time point when comparing TFA-S100 – immunized and control mice (Figure 1D). These results showed that splenic granulocytes expressing the MIP-2 or KC receptor, CXCR2, were evident following immunizations with TFA-S100 or with CFA alone and further suggested that recruitment of these cells to the liver was most likely regulated by hepatic expression of neutrophil chemokines MIP-2 and KC.

Hepatic expression of MIP-2 increases neutrophilic inflammation in experimental DILI

MIP-2 and KC are C-X-C chemokines that have been shown to target neutrophils following injury or infection [29] and are also expressed in situ in the areas of tissue inflammation [30]. Previously we showed that female BALB/c (WT) mice develop significantly more experimental hepatitis than less susceptible female IL-4 −/− (KO) mice at 3 weeks following immunization with TFA-S100 (Figure 1A). Hence, we measured MIP-2 and KC levels in liver tissue supernatants at baseline as well as following TFA-S100 immunizations of susceptible WT and less susceptible KO mice. To verify that immunization induced differences in MIP-2 and KC specifically in the liver, these chemokines were measured simultaneously in the spleen.

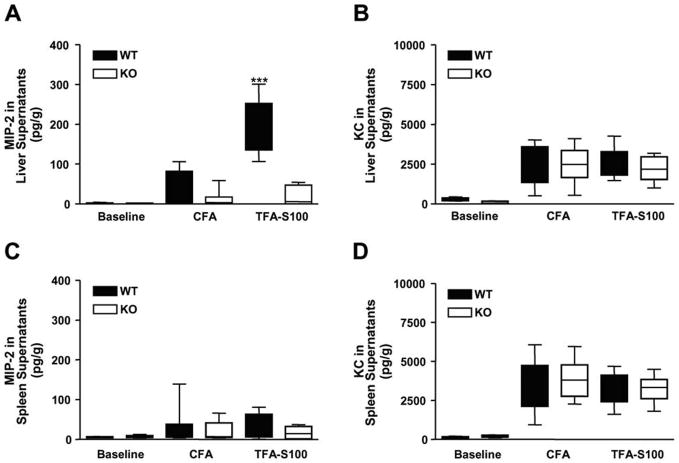

Concurrent with significant neutrophilic hepatitis, we found that hepatic MIP-2 levels were higher in WT than KO mice (p < 0.001) (Figure 2A); however, KC levels in the liver were not significantly different between groups (Figure 2B). MIP-2 and KC levels in liver tissue supernatants did not differ significantly between WT or KO mice at baseline or following CFA alone (Figure 2A and B) or in spleen supernatants following immunization (Figures 2C and D). Taken together with previous investigations as well as ours [30], these results strongly suggested that MIP-2 increased hepatic neutrophilic inflammation in experimental anesthetic DILI by recruiting CXCR2+ neutrophils, possibly from the spleen or other secondary lymphoid sites.

Figure 2. MIP-2, but not KC, is elevated in liver supernatants from WT mice.

(A) Concurrent with significant neutrophilic hepatitis at 3 weeks, MIP-2 levels in hepatic supernatants were significantly higher in WT (196.1 ± 22.5 pg/g) when compared to KO mice (19.8 ±7.4 pg/g, ***p < 0.001), but were similar at baseline and following CFA. (B) Hepatic KC levels as well as splenic (C) MIP-2 and (D) KC levels were not significantly different between WT and KO mice at baseline or following CFA ± TFA-S100. Experiments were run in duplicate (N = 10 mice/group).

Hepatic MIG and IP-10 levels are not significantly different 3 weeks following TFA-S100 immunization

Viral models of hepatitis have demonstrated that the IFN-γ – dependent chemokines MIG and IP-10 have essential roles in recruiting effector Th1 cells into sites of infection in the liver [31]. Moreover, while performing this function MIG and especially IP-10 can also skew Th1 inflammation by inhibiting recruitment of Th2 cells [27]. Since we found that hepatic inflammation was primarily composed of neutrophils, and since we did not find increases in the frequency of T cells in the liver (Figure 1B), we did not expect to find significant roles for MIG or IP-10 in the development of inflammation during the hepatic effector phase. Even so, we initially measured MIG and IP-10 in liver tissue supernatants 3 weeks following immunization of susceptible WT and less susceptible KO mice. For comparison, splenic levels of both of these chemokines were measured at baseline as well as following immunizations.

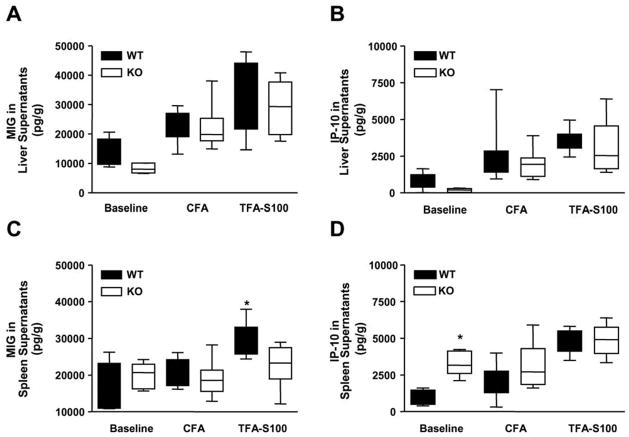

Hepatic MIG and IP-10 levels did not differ at 3 weeks between WT and KO mice or at baseline or following immunizations (Figures 3A and B). This finding further supported our view that MIG or IP-10 did not significantly affect the development of inflammation during the effector hepatic inflammatory phase of experimental anesthetic DILI. However, when we measured splenic levels of MIG at the same time point after immunizations, we found that the levels of MIG were higher in WT than in KO mice (Figure 3C, p < 0.05). When taken together with previous studies where MIG had been shown to have a role in skewing Th1 inflammation [27], this finding suggested that MIG or IP-10 may prevent further recruitment of neutrophils to the liver. Alternatively, splenic recruitment or splenic sequestration of Th1 cells by MIG [31] may have also encouraged the development of hepatic neutrophilic inflammation in WT mice by preventing efflux to the liver of potentially protective T cells.

Figure 3. Elevated splenic MIG levels are found during the effector inflammatory hepatitis phase of experimental DILI while baseline IP-10 levels are higher in KO mice.

(A) MIG and (B) IP-10 levels in liver supernatants were not significantly different between WT or KO mice at baseline or following CFA ± TFA-S100. (C) Following TFA-S100 immunizations, splenic MIG levels were significantly higher in WT (29747 ± 1361 pg/g) when comparing them to KO mice (22760 ± 5079 pg/g, *p < 0.05) but were not significantly different between groups at baseline or following CFA. (D) Baseline splenic IP-10 levels were higher in KO when compared to WT mice (1024 ± 235.3 pg/g and 3326 ± 380.2 pg/g, respectively, *p < 0.05), but were not significantly different in WT or KO mice following CFA ± TFA-S100. All experiments were run in duplicate (N = 10 mice/group).

Elevated Splenic IP-10 levels were detected during the T cell priming phase of experimental DILI in less susceptible IL-4 −/− (KO) mice

Because IP-10 more than MIG had been shown to skew Th1 inflammation by inhibiting recruitment of Th2 cells [27], we investigated IP-10 levels in the spleen at baseline and following immunizations. Baseline IP-10 levels in spleen supernatants were significantly lower in susceptible WT than less susceptible KO mice (Figure 3D, p < 0.05). This finding suggested that one possible reason for WT susceptibility to experimental DILI could have arisen from decreased baseline levels of splenic IP-10. Additionally, our finding could infer a role for IP-10 in the priming phase of experimental DILI suggesting that the role of IP-10 may diminish once significant hepatitis occurs at 3 weeks.

Previously, we demonstrated a splenic priming phase prior to the development of experimental DILI by examining splenocytes and supernatants from WT mice two weeks following immunizations [7]. Significantly elevated proinflammatory and regulatory cytokines [7] as well as splenocyte proliferation were demonstrated in TFA-S100 primed cells following re-stimulation with CYP2E1 and KLH-TFA (Njoku et al., manuscript submitted). We also found that splenic CD4+T cells from WT mice proliferated significantly higher than cells from KO mice following re-stimulation with CYP2E1 and KLH-TFA (Njoku, et al., manuscript submitted) suggesting that IL-4 had a significant role in the priming phase of experimental DILI. Based on this finding we investigated whether IP-10 was associated with diminished T cell priming responses in KO mice by measuring expression of the IP-10 receptor CXCR3 at two weeks in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from TFA-S100 – primed WT and KO mice as well as IP-10 levels in splenocyte supernatants 72h following incubation in media ± CYP2E1 or TFA.

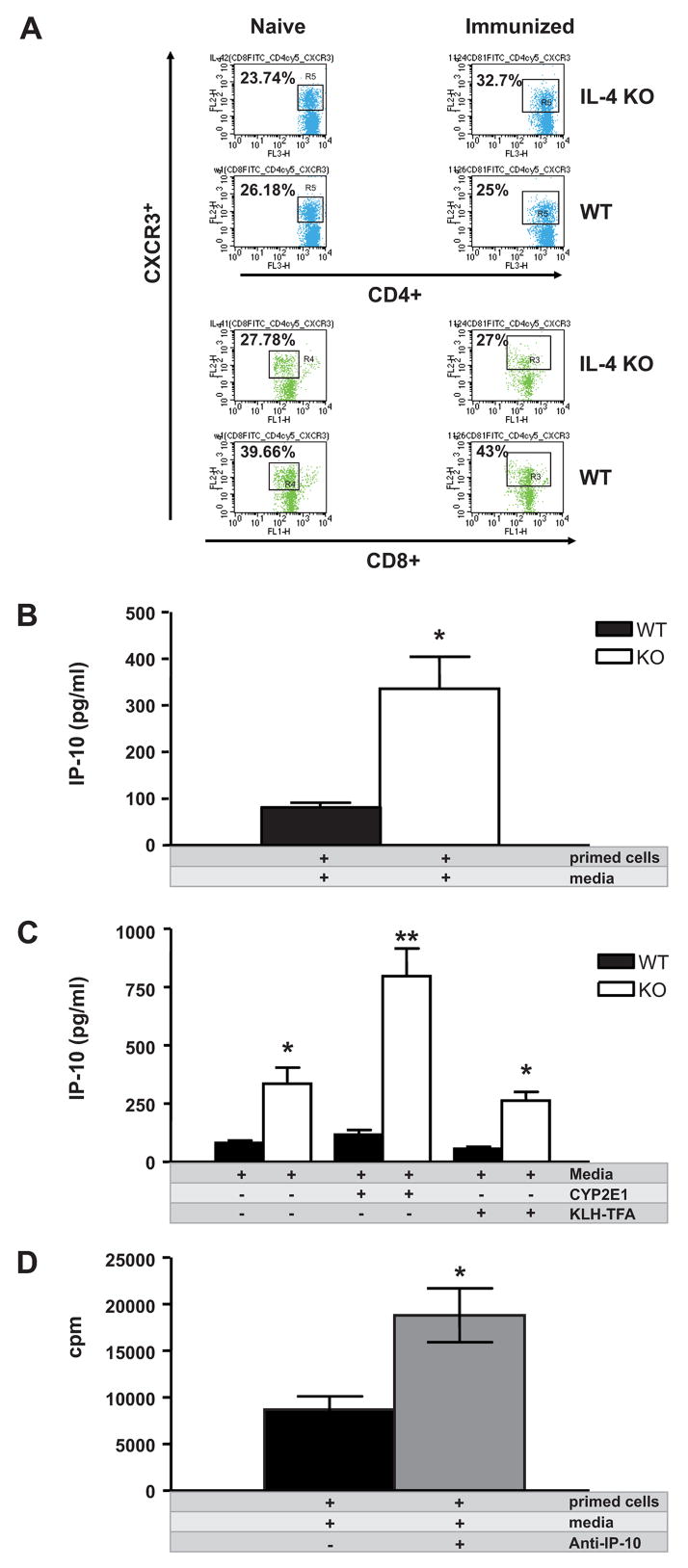

CXCR3 expression was similar at baseline and two weeks following immunizations in CD4+ and CD8+ from WT spleens; however, CXCR3 expression was increased in CD4+ T cells from KO spleens (Figure 4A) suggesting that IP-10 – expression was up-regulated in KO spleens during T cell priming. In splenocyte supernatants, we found that IP-10 levels were significantly higher in TFA-S100 primed cells from KO mice when compared to those from TFA-S100 –immunized WT mice (Figure 4B, p < 0.05). This finding suggested to us that elevated levels of IP-10 were associated with diminished T cell priming in KO mice, and thus may have a protective regulatory role by influencing the ability of KO mice to augment T cell priming.

Figure 4. IP-10 down-regulates T cell proliferation in TFA-S100 primed WT splenocytes through increased recruitment of CXCR3+ splenic CD4+T cells in KO mice.

(A) CXCR3 expression was similar at baseline and two weeks following TFA-S100 immunizations in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from WT spleens; however, CXCR3 expression was increased in CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells from KO spleens. (B) Splenic supernatant IP-10 levels were significantly higher in primed cells from KO (335.5 ± 68.8 pg/ml) when compared to WT mice (81.6 ± 9.3 pg/ml, *p < 0.05). (C) IP-10 levels were significantly higher in KO (797.1 ± 118 pg/ml) mouse supernatants from splenocytes re-stimulated with CYP2E1 (262.7 ± 37.4 pg/ml, **p < 0.01) or KLH-TFA (*p < 0.05) when compared to WT mice. (D) Co-culture of TFA-S100 primed splenocytes (2 × 105/100μl) with anti-IP-10 (0.9 μg/ml) increased proliferation by 24h as measured by thymidine incorporation (*p < 0.05). All experiments were run in duplicate (N = 4 –5 mice/group).

Next we measured IP-10 levels in culture supernatants from TFA-S100 – primed splenocytes from both WT and KO mice re-stimulated with key antigens CYP2E1 and TFA. IP-10 levels were significantly higher in KO mouse supernatants obtained from splenocytes which were re-stimulated in vitro with CYP2E1 when compared to WT mice (Figure 4C, p < 0.01). A similar pattern was demonstrated in supernatants from KO splenocytes re-stimulated with KLH-TFA (Figure 4C, p < 0.05) when compared to WT mice. These findings suggested that IP-10 had a critical protective role in decreasing T cell proliferation during the priming phase of experimental anesthetic DILI. This finding also confirmed that in addition to resulting in significantly diminished hepatitis, splenocytes from KO mice also exhibited minimal proliferation to key DILI – associated antigens during the T cell priming phase of experimental DILI (Njoku et al., manuscript submitted).

IP-10 diminishes T cell proliferation in TFA-S100 primed WT splenocytes

Thus far our investigations inferred that IP-10 diminished T cell proliferation following immunization with TFA-S100. However, it was not clear whether IP-10 levels in KO mice were heavily skewed because of the absence of IL-4 in these mice. Moreover, although doses of our antigen used to re-stimulate TFA-S100 – primed splenocytes in WT and KO mice were relatively low (10 μg/ml), we had no way of knowing whether these doses of re-stimulating antigen may have skewed the observed IP-10 responses.

To more fully understand the role of IP-10 in the priming phase of experimental immune DILI, we investigated the action of IP-10 on TFA-S100 – primed splenocytes in susceptible WT mice. We measured proliferation in cultured splenocytes from TFA-S00 – primed WT mice with or without anti-IP-10. Co-culture of TFA-S100 primed splenocytes with anti-IP-10 increased proliferation as measured by thymidine incorporation (Figure 4D, p < 0.05). This data suggested that IP-10 diminished splenocyte proliferation initiated by TFA-S100 immunizations, strongly suggesting that IP-10 reduced T cell priming during the induction of experimental DILI. This finding is an important discovery since T cell proliferation during the priming phase had been associated with the development of experimental DILI in WT mice [7]. It further suggested a protective effect of IP-10 in the development of experimental DILI.

Discussion

In susceptible patients, immune – mediated DILI is a complex disease process characterized by various degrees of hepatic inflammation and injury as well as systemic signs such as rash, joint inflammation, autoantibodies and antibodies to drug haptens [32–35]. A murine model for immune-mediated DILI from halogenated anesthetics (or any drug hapten) with autoimmune features has not previously been developed. Drugs such as halogenated anesthetics, phenytoin, tegretol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or alcohol that cause DILI are believed to do so through the development of hapten-autoantigens [4–7]. The aim of this study was to investigate how chemokines modulate experimental DILI. We compared susceptible BALB/c (WT) with IL-4−/− (KO) mice that develop significantly less hepatitis. We advance knowledge in the immunological basis of this disease by demonstrating that hepatitis can be promoted by hepatic MIP-2 while proliferation to key DILI antigens is diminished by splenic IP-10 during T cell priming.

We demonstrated a critical role for MIP-2 in the generation of neutrophilic hepatitis in experimental DILI. Prior studies have also reported the importance of neutrophils in immune – mediated hepatitis induced by Con A. These studies showed that neutrophils regulate hepatitis and liver injury by initiating CD4+T cell recruitment to the liver [36,37]. Subsequent studies revealed that the production of critical cytokines IL-4 and TNF-α as well as chemokines MIP-2 and KC by Kupffer cells contributes to Con A – induced hepatitis [38]. Similarly, we have previously found a critical role for Kupffer cells [7], TNF-α [7] and IL-4 (Njoku et al., submitted) in the generation experimental DILI. However, concurrent with the onset of neutrophilic hepatitis, we demonstrate significantly elevated levels of MIP-2 but not KC in liver supernatants from WT but not KO mice (Figure 2A). Taken together with our previous investigations, this finding further suggests that MIP-2 generated by Kupffer cells [38] affects development of neutrophilic inflammation in the liver through recruitment of CXCR2+ neutrophils from the spleen, other secondary lymphoid organs, or, as one recent study suggests, even the bone marrow [39]. These findings also confirm our prior hypothesis suggesting a critical role for Kupffer cells in the initiation of anesthetic DILI [7].

Previous reports have demonstrated specific roles for MIP-2 and KC in the development of inflammation following injury or infection. These studies have clearly shown that KC expressed in endothelial cells attracts neutrophils early following injury, while the action of MIP-2 expressed on neutrophils occurs at a later time point [30]. Another study has also suggested an early effect of KC in inducing hepatic CXCR2 receptor and MIP-2 expression [40]. Similar to our findings, studies directly investigating mechanisms of CXC chemokine induction of neutrophilic inflammation in the liver clearly demonstrate that MIP-2 is a more potent inducer of neutrophil activation than KC [41].

We provide evidence for a protective role for IP-10 in the initiation of experimental immune – mediated anesthetic DILI. In contrast to our findings, IP-10 has been shown to worsen other hepatic inflammatory conditions in patients such as hepatitis B [42,43], hepatitis C [44,45], AIH [23,24] and primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) [46], as well as T cell hepatitis induced by Con A [1]. At first glance it would seem that our studies suggest an opposing effect of IP-10 in experimental DILI or even immune – mediated DILI in patients. Moreover similar to our model of anesthetic DILI, modification of native proteins by drugs is also believed to have a role in the pathogenesis of PBC [47]. However, AIH, PBC and Con A are associated with a predominantly T cell hepatitis, whereas the immune – mediated DILI associated with halogenated volatile anesthetics is characterized mainly by neutrophilic and monocytic inflammation. Thus, our findings propose alternative mechanisms for T cells and their chemokines in hepatic conditions where granulocytic inflammation has a key role in the pathogenesis. Along these lines, prior studies have suggested a protective role for IP-10 in acetaminophen – induced, acute toxic hepatitis, which is characterized by granulocytic inflammation, by promoting hepatic regeneration through CXCR2 expression on hepatocytes [26].

We found that administration of anti-IP-10 in vitro increases proliferation of TFA-S100 primed WT splenocytes, suggesting that IP-10 regulates T cell priming and may decrease the development of hepatitis in our model. In contrast to our findings, a prior study has shown that direct injection of anti-IP-10 in vivo following the induction of hapten-based contact hypersensitivity significantly reduced the development of contact hypersensitivity [48], suggesting that IP-10 may have an additional role in the effector phase of hapten - based delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. We have not investigated whether IP-10 plays a similar role in the effector hepatic inflammatory phase of experimental DILI. This issue is currently a subject of further investigation in our laboratory. At this time, our analysis of hepatic IP-10 at the 3- week time point post induction of anesthetic DILI suggests that the effect of IP-10 seen in delayed- type hypersensitivity may not be relevant in our model (Figure 3D).

A prior study clearly showed that IP-10 and MIG have additional functions in sequestering Th1 cells in sites of infection and inflammation [31]. This suggests that these chemokines could contribute to the accumulation of potentially protective cells in sites of viral clearance. These cells may even be sequestered in sites distal to where potentially protective mechanisms would be required. This latter mechanism may be involved in the pathogenesis of experimental DILI in our model since female WT mice, which are more susceptible to neutrophilic hepatitis than KO mice, have increased MIG in the spleen during the height of hepatic neutrophilic inflammation (Figure 3C). Moreover, since neutrophils can produce MIG and IP-10, we also speculate that neutrophil-derived MIG and IP-10 can recruit Th1 cells that further regulate neutrophil – derived immune responses [49].

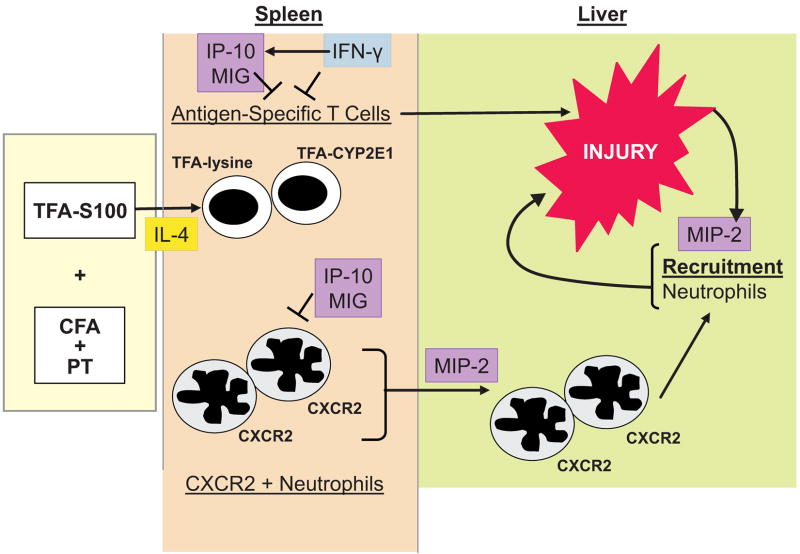

In summary, we suggest that the pathogenesis of experimental anesthetic DILI is dependent on elevated hepatic MIP-2 expression which promotes neutrophilic migration to the liver, most likely from the spleen. Additionally, splenic expression of the IFN-γ – dependent Th1 cell chemokine MIG may regulate the development of neutrophilic hepatitis through recruitment or sequestration of Th1 cells in the spleen. We confirm that splenic IP-10 modulates T cell priming to critical liver antigens and drug haptens during the initiation phase of experimental DILI, and that IP-10 thereby regulates the development of hepatitis (Figure 5). Our studies emphasize complex and compound roles for chemokines in the pathogenesis of experimental immune – mediated DILI. Further investigations of the roles these chemokines play in the different stages of immune mediated DILI in experimental models and in patients may aid in the discovery of novel targets that modulate the development of immune – mediated DILI from halogenated volatile anesthetics or other drugs such as antibiotics, tienilic acid, carbamazepine or alcohol.

Figure 5. IP-10 diminishes T cell priming while MIP-2 promotes neutrophilic hepatitis in experimental, immune-mediated DILI.

We propose that IP-10 regulates CYP2E1 and TFA-lysine (TFA-Lys) induced CD4+ T proliferation following TFA-S100 immunizations by reducing T cell proliferation to these key antigens. IP-10 and MIG may also regulate neutrophil responses by diminishing CXCR2+ neutrophil migration during T cell priming. In contrast, MIP-2 signaling from the liver promotes the development of hepatitis by promoting migration of CXCR2+ neutrophils from the spleen or other secondary lymphoid organs.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a grant from NIHR21DK075828 to DBN and in part by grants from the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Scoby and The Gail I Zuckerman Foundation.

The authors would like to sincerely thank Dr. Davinna Ligons for her technical support and Dr. Eyal Talor for his critical reading of this manuscript.

Abbreviations in this article

- AIH

autoimmune hepatitis

- CYP2E1

cytochrome P450 2E1

- DILI

drug – induced liver injury

- IP-10

interferon gamma inducible protein – 10

- KC

Keratinocyte – derived chemokine

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- MIP-2

macrophage inflammatory protein – 2

- MIG

monokine induced by interferon gamma

- PT

pertussis toxin

- TFA

trifluoroacetyl chloride

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zhou R, Tang W, Ren YX, He PL, Yang YF, Li YC, Zuo JP. Preventive effects of (5R)-5-hydroxytriptolide on concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;537:181–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourdi M, Chen W, Peter RM, Martin JL, Buters JT, Nelson SD, Pohl LR. Human cytochrome P450 2E1 is a major autoantigen associated with halothane hepatitis. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:1159–66. doi: 10.1021/tx960083q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackay IR, Toh BH. Autoimmune hepatitis: the way we were, the way we are today and the way we hope to be. Autoimmunity. 2002;35:293–305. doi: 10.1080/08916930290015610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuberger J, Mieli-Vergani G, Tredger JM, Davis M, Williams R. Oxidative metabolism of halothane in the production of altered hepatocyte membrane antigens in acute halothane-induced hepatic necrosis. Gut. 1981;22:669–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.22.8.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pohl LR, Thomassen D, Pumford NR, Butler LE, Satoh H, Ferrans VJ, Perrone A, Martin BM, Martin JL. Hapten carrier conjugates associated with halothane hepatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;283:111–20. 111–20. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5877-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Njoku D, Laster MJ, Gong DH, Eger EI, Reed GF, Martin JL. Biotransformation of halothane, enflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane to trifluoroacetylated liver proteins: association between protein acylation and hepatic injury. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:173–78. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199701000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Njoku DB, Talor MV, Fairweather D, Frisancho-Kiss S, Odumade OA, Rose NR. A novel model of drug hapten-induced hepatitis with increased mast cells in the BALB/c mouse. Exp Mol Pathol. 2005;78:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molnar RG, Wang P, Ayala A, Ganey PE, Roth RA, Chaudry IH. The role of neutrophils in producing hepatocellular dysfunction during the hyperdynamic stage of sepsis in rats. J Surg Res. 1997;73:117–22. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawson JA, Farhood A, Hopper RD, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H. The hepatic inflammatory response after acetaminophen overdose: role of neutrophils. Toxicol Sci. 2000;54:509–16. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/54.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taieb J, Chollet-Martin S, Cohard M, Garaud JJ, Poynard T. The role of interleukin-10 in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Clin Biochem. 2001;34:237–38. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(01)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregory SA, Webster JB, Chapman GD. Acute hepatitis induced by parenteral amiodarone. Am J Med. 2002;113:254–55. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham BN, Bemuau J, Durand F, Sauvanet A, Degott C, Prin L, Janin A. Eotaxin expression and eosinophil infiltrate in the liver of patients with drug-induced liver disease. J Hepatol. 2001;34:537–47. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis H, Le Moine A, Flamand V, Nagy N, Quertinmont E, Paulart F, Abramowicz D, Le Moine O, Goldman M, Deviere J. Critical role of interleukin 5 and eosinophils in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:2001–10. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsutsui H, Matsui K, Okamura H, Nakanishi K. Pathophysiological roles of interleukin-18 in inflammatory liver diseases. Immunol Rev. 2000;174:192–209. 192–209. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sass G, Heinlein S, Agli A, Bang R, Schumann J, Tiegs G. Cytokine expression in three mouse models of experimental hepatitis. Cytokine. 2002;19:115–20. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yumoto E, Higashi T, Nouso K, Nakatsukasa H, Fujiwara K, Hanafusa T, Yumoto Y, Tanimoto T, Kurimoto M, Tanaka N, Tsuji T. Serum gamma-interferon-inducing factor (IL-18) and IL-10 levels in patients with acute hepatitis and fulminant hepatic failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:285–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colantoni A, Idilman R, De Maria N, La Paglia N, Belmonte J, Wezeman F, Emanuele N, Van Thiel DH, Kovacs EJ, Emanuele MA. Hepatic apoptosis and proliferation in male and female rats fed alcohol: role of cytokines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1184–89. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000075834.52279.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enomoto N, Takei Y, Hirose M, Kitamura T, Ikejima K, Sato N. Protective effect of thalidomide on endotoxin-induced liver injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:2S–6S. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000078606.59842.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Endlich B, Armstrong D, Brodsky J, Novotny M, Hamilton TA. Distinct temporal patterns of macrophage-inflammatory protein-2 and KC chemokine gene expression in surgical injury. J Immunol. 2002;168:3586–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong DA, Major JA, Chudyk A, Hamilton TA. Neutrophil chemoattractant genes KC and MIP-2 are expressed in different cell populations at sites of surgical injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:641–48. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0803370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rovai LE, Herschman HR, Smith JB. The murine neutrophil-chemoattractant chemokines LIX, KC, and MIP-2 have distinct induction kinetics, tissue distributions, and tissue-specific sensitivities to glucocorticoid regulation in endotoxemia. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:494–502. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall LR, Diaconu E, Patel R, Pearlman E. CXC chemokine receptor 2 but not C-C chemokine receptor 1 expression is essential for neutrophil recruitment to the cornea in helminth-mediated keratitis (river blindness) J Immunol. 2001;166:4035–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopydlowski KM, Salkowski CA, Cody MJ, van Rooijen N, Major J, Hamilton TA, Vogel SN. Regulation of macrophage chemokine expression by lipopolysaccharide in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;163:1537–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaruga B, Hong F, Kim WH, Gao B. IFN-gamma/STAT1 acts as a proinflammatory signal in T cell-mediated hepatitis via induction of multiple chemokines and adhesion molecules: a critical role of IRF-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G1044–G1052. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00184.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishida Y, Kondo T, Ohshima T, Fujiwara H, Iwakura Y, Mukaida N. A pivotal involvement of IFN-gamma in the pathogenesis of acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. FASEB J. 2002;16:1227–36. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0046com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bone-Larson CL, Hogaboam CM, Evanhoff H, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL. IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 (CXCL10) is hepatoprotective during acute liver injury through the induction of CXCR2 on hepatocytes. J Immunol. 2001;167:7077–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Booth V, Keizer DW, Kamphuis MB, Clark-Lewis I, Sykes BD. The CXCR3 binding chemokine IP-10/CXCL10: structure and receptor interactions. Biochemistry. 2002;20(41):10418–25. doi: 10.1021/bi026020q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howell CD, Yoder TD. Murine experimental autoimmune hepatitis: nonspecific inflammation due to adjuvant oil. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;72:76–82. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerard C, Rollins BJ. Chemokines and disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:108–15. doi: 10.1038/84209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang S, Paulauskis JD, Godleski JJ, Kobzik L. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 and KC mRNA in pulmonary inflammation. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:981–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arai K, Liu ZX, Lane T, Dennert G. IP-10 and Mig facilitate accumulation of T cells in the virus-infected liver. Cell Immunol. 2002;219:48–56. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Njoku DB, Shrestha S, Soloway R, Duray PR, Tsokos M, Abu-Asab MS, Pohl LR, West AB. Subcellular localization of trifluoroacetylated liver proteins in association with hepatitis following isoflurane. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:757–61. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200203000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson JS, Rose NR, Martin JL, Eger EI, Njoku DB. Desflurane hepatitis associated with hapten and autoantigen-specific IgG4 antibodies. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1452–3. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000263275.10081.47. table. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen C, Rose NR, Njoku DB. Trifluoroacetylated IgG4 antibodies in a child with idiosyncratic acute liver failure after first exposure to halothane. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:199–202. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181709fee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chin MW, Njoku DB, Macquillan G, Cheng WS, Kontorinis N. Desflurane-induced acute liver failure. Med J Aust. 2008;189:293–94. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb02035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonder CS, Ajuebor MN, Zbytnuik LD, Kubes P, Swain MG. Essential role for neutrophil recruitment to the liver in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. J Immunol. 2004;172:45–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatada S, Ohta T, Shiratsuchi Y, Hatano M, Kobayashi Y. A novel accessory role of neutrophils in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. Cell Immunol. 2005;233:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatano M, Sasaki S, Ohata S, Shiratsuchi Y, Yamazaki T, Nagata K, Kobayashi Y. Effects of Kupffer cell-depletion on Concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. Cell Immunol. 2008;251:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serbina NV, Pamer EG. Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:311–17. doi: 10.1038/ni1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stefanovic L, Brenner DA, Stefanovic B. Direct hepatotoxic effect of KC chemokine in the liver without infiltration of neutrophils. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:573–86. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bajt ML, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Effects of CXC chemokines on neutrophil activation and sequestration in hepatic vasculature. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1188–G1195. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Zhao JH, Wang PP, Xiang GJ. Expression of CXC chemokine IP-10 in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng G, Zhou G, Zhang R, Zhai Y, Zhao W, Yan Z, Deng C, Yuan X, Xu B, Dong X, Zhang X, Zhang X, Yao Z, Shen Y, Qiang B, Wang Y, He F. Regulatory polymorphisms in the promoter of CXCL10 gene and disease progression in male hepatitis B virus carriers. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:716–26. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lagging M, Romero AI, Westin J, Norkrans G, Dhillon AP, Pawlotsky JM, Zeuzem S, von Wagner M, Negro F, Schalm SW, Haagmans BL, Ferrari C, Missale G, Neumann AU, Verheij-Hart E, Hellstrand K. IP-10 predicts viral response and therapeutic outcome in difficult-to-treat patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. Hepatology. 2006;44:1617–25. doi: 10.1002/hep.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romero AI, Lagging M, Westin J, Dhillon AP, Dustin LB, Pawlotsky JM, Neumann AU, Ferrari C, Missale G, Haagmans BL, Schalm SW, Zeuzem S, Negro F, Verheij-Hart E, Hellstrand K. Interferon (IFN)-gamma-inducible protein-10: association with histological results, viral kinetics, and outcome during treatment with pegylated IFN-alpha 2a and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:895–903. doi: 10.1086/507307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chuang YH, Lian ZX, Cheng CM, Lan RY, Yang GX, Moritoki Y, Chiang BL, Ansari AA, Tsuneyama K, Coppel RL, Gershwin ME. Increased levels of chemokine receptor CXCR3 and chemokines IP-10 and MIG in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and their first degree relatives. J Autoimmun. 2005;25:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rieger R, Gershwin ME. The X and why of xenobiotics in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Autoimmun. 2007;28:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakae S, Komiyama Y, Narumi S, Sudo K, Horai R, Tagawa Y, Sekikawa K, Matsushima K, Asano M, Iwakura Y. IL-1-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha elicits inflammatory cell infiltration in the skin by inducing IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 in the elicitation phase of the contact hypersensitivity response. Int Immunol. 2003;15:251–60. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gasperini S, Marchi M, Calzetti F, Laudanna C, Vicentini L, Olsen H, Murphy M, Liao F, Farber J, Cassatella MA. Gene expression and production of the monokine induced by IFN-gamma (MIG), IFN-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC), and IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) chemokines by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1999;162:4928–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]